Unlocking Protein Function: A Guide to Hidden Representations in Protein Sequence Space

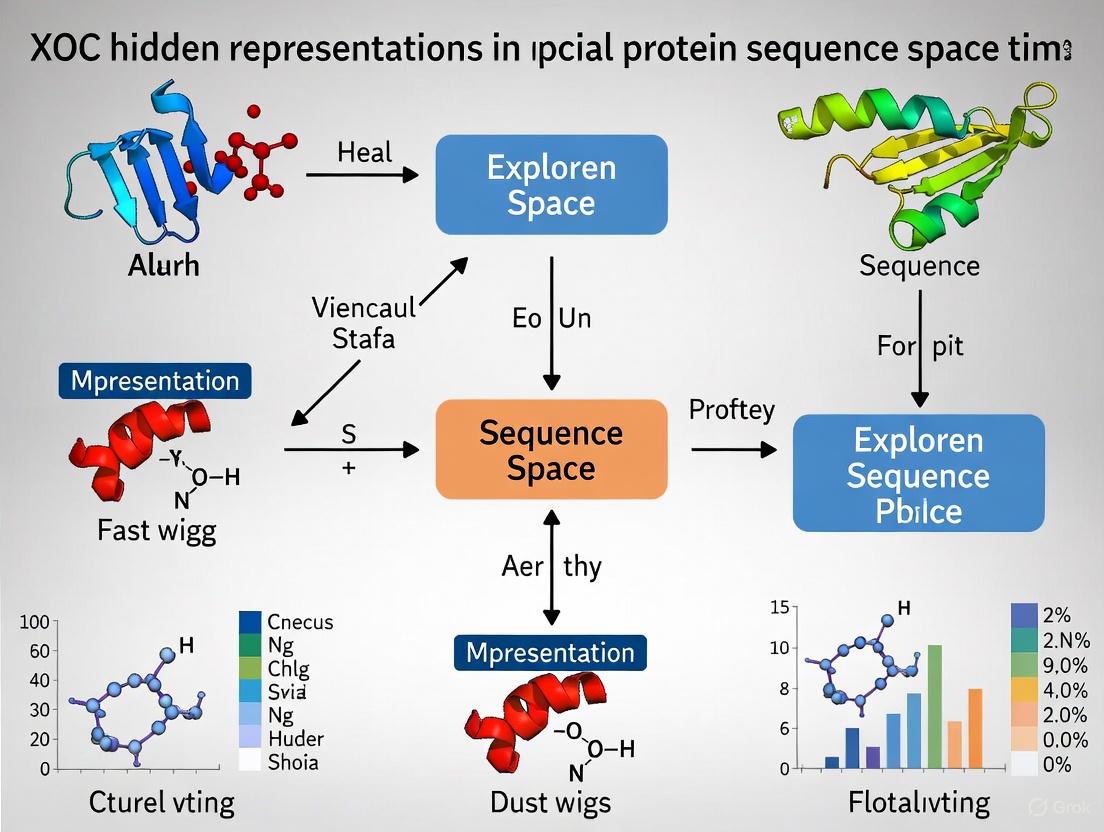

This article explores the transformative role of hidden representations in protein sequence space, a frontier where machine learning deciphers the complex language of proteins.

Unlocking Protein Function: A Guide to Hidden Representations in Protein Sequence Space

Abstract

This article explores the transformative role of hidden representations in protein sequence space, a frontier where machine learning deciphers the complex language of proteins. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, we cover foundational concepts, from defining protein sequence spaces to the mechanics of Protein Language Models (PLMs) that generate these powerful embeddings. The review details cutting-edge methodological advances and their direct applications in drug repurposing and protein design, exemplified by tools like LigandMPNN. It also addresses critical challenges in interpretation and optimization, providing insights into troubleshooting representation quality. Finally, we present a rigorous comparative analysis of validation frameworks, from statistical benchmarks to real-world experimental success stories, offering a comprehensive resource for leveraging these representations to accelerate biomedical discovery.

The Landscape of Protein Sequence Space: From Amino Acid Chains to Intelligent Embeddings

For the past half-century, structural biology has operated on a fundamental assumption: similar protein sequences give rise to similar structures and functions. This sequence-structure-function paradigm has guided research to explore specific regions of the protein universe while inadvertently neglecting others. Hidden representations within protein sequence space contain critical information that transcends this traditional assumption, enabling functions to emerge from divergent sequences and structures. Understanding this complex mapping represents one of the most significant challenges in modern computational biology. The microbial protein universe reveals that functional similarity can be achieved through different sequences and structures, suggesting a more nuanced relationship than previously assumed [1]. This whitepaper explores the core principles defining the protein sequence universe, examining the mathematical relationships between sequence space and structural conformations, with particular emphasis on the role of machine learning in deciphering this biological language.

Recent advances in protein structure prediction, notably through AlphaFold2 and RoseTTAFold, have revolutionized our ability to explore previously inaccessible regions of the protein universe. These tools have shifted the perspective from a relative paucity of structural information to a relative abundance, enabling researchers to answer fundamental questions about the completeness and continuity of protein fold space [1] [2]. Simultaneously, protein language models (PLMs) have emerged as powerful tools for extracting hidden representations from sequence data alone, transforming sequences into multidimensional vectors that encode structural and functional information [3]. This technical guide examines the core principles, methodologies, and tools defining our current understanding of the protein sequence universe, framed within the broader context of hidden representation research.

The Theoretical Framework of Sequence-Structure Relationships

Fundamental Principles

The relationship between protein sequence, structure, and function represents a multi-dimensional mapping problem with profound implications for evolutionary biology and protein design. The local sequence-structure relationship demonstrates that while the correlation is not overwhelmingly strong compared to random assignment, distinct patterns of amino acid specificity exist for adopting particular local structural conformations [4]. Research analyzing over 4,000 protein structures from the PDB has enabled the hierarchical clustering of the 20 amino acids into six distinct groups based on their similarity in fitting local structural space, providing a scoring rubric for quantifying the match of an amino acid to its putative local structure [4].

The classical view that sequence determines structure, which in turn determines function, is being refined through the analysis of massive structural datasets. Studies of the microbial protein universe reveal that functional convergence can occur through different structural solutions, challenging the strict linear paradigm [1]. This discovery highlights the need for a shift in perspective across all branches of biology—from obtaining structures to putting them into context, and from sequence-based to sequence-structure-function-based meta-omics analyses.

The Language of Life: Analogies and Computational Representations

Protein sequences can be conceptualized as a biological language where amino acids constitute the alphabet, structural motifs form the vocabulary, and functional domains represent complete sentences. This analogy extends to computational approaches, where natural language processing (NLP) techniques are applied to protein sequences to predict structural features and functional properties. Protein language models learn the "grammar" of protein folding by training on millions of sequences, enabling them to generate novel sequences with predicted functions [3].

The representation of local protein structure using two angles, θ and μ, provides a simplified framework for analyzing sequence-structure relationships across diverse protein families [4]. This parameterization facilitates the comparison of local structural environments and the identification of amino acid preferences for specific conformational states, contributing to our understanding of how sequence encodes structural information.

Quantitative Landscape of the Protein Universe

Structural Space Saturation and Novelty

Large-scale structural prediction efforts have revealed fundamental properties of the protein universe. Analysis of ~200,000 microbial protein structures predicted from 1,003 representative genomes across the microbial tree of life demonstrates that the structural space is continuous and largely saturated [1]. This continuity suggests that evolutionary innovations often occur through recombination and modification of existing structural motifs rather than de novo invention of completely novel architectures.

Table 1: Novel Fold Discovery in Microbial Protein Universe

| Database/Resource | Total Structures Analyzed | Novel Folds Identified | Verification Method | Structural Coverage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MIP Database | ~200,000 | 148 novel folds | AlphaFold2 verification | Microbial proteins (40-200 residues) |

| AlphaFold Database | >200 million | N/A | N/A | Primarily Eukaryotic |

| CATH (v4.3.0) | N/A | ~6,000 folds | Experimental structures | PDB90 non-redundant set |

The identification of 148 novel folds from microbial sequences highlights that significant discoveries remain possible, particularly in understudied organisms and sequence spaces [1]. These novel folds were identified by comparing models against representative domains in CATH and the PDB using a TM-score cutoff of 0.5, with subsequent verification by AlphaFold2 reducing false positives from 161 to 148 fold clusters [1].

Database Orthogonality and Structural Coverage

Different structural databases offer complementary coverage of the protein universe. The MIP database specializes in microbial proteins from Archaea and Bacteria with sequences between 40-200 residues, while the AlphaFold database predominantly covers Eukaryotic proteins [1]. This orthogonality is significant, as only approximately 3.6% of structures in the AlphaFold database belong to Archaea and Bacteria, highlighting the unique contribution of microbial-focused resources [1].

Table 2: Protein Structure Database Characteristics

| Database | Source Organisms | Sequence Length Focus | Prediction Methods | Unique Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MIP Database | Archaea and Bacteria | 40-200 residues | Rosetta, DMPfold | Per-residue functional annotations via DeepFRI |

| AlphaFold DB | Primarily Eukaryotes | Full-length proteins | AlphaFold2 | Comprehensive eukaryotic coverage |

| PDB90 | Diverse organisms | Experimental structures | Experimental methods | Non-redundant subset of PDB |

| CATH | Diverse organisms | Structural domains | Curated classification | Hierarchical fold classification |

The average structural domain size for microbial proteins is approximately 100 residues, explaining the focus on shorter sequences in microbial-focused databases [1]. This length distribution reflects fundamental differences in protein architecture between microbial and eukaryotic organisms, with the latter containing more multi-domain proteins and longer sequences.

Methodological Approaches for Mapping the Sequence Universe

Large-Scale Structure Prediction and Quality Assessment

Large-scale structure prediction initiatives have employed sophisticated quality assessment metrics to ensure model reliability. The Microbiome Immunity Project (MIP) utilized a three-step quality control process: (1) filtering by coil content with varying thresholds for different methods (Rosetta models with >60% coil content, DMPFold models with >80% coil content were filtered out), (2) method-specific quality metrics (DMPFold confidence score and Rosetta MQA score derived from pairwise TM-scores of the 10 lowest-scoring models), and (3) inter-method agreement (TM-score ≥ 0.5 between Rosetta and DMPFold models) [1].

The following workflow illustrates the comprehensive process for large-scale structure prediction and analysis:

Diagram 1: Large-Scale Structure Prediction Workflow (76 characters)

This workflow begins with the Genomic Encyclopedia of Bacteria and Archaea (GEBA1003) reference genome database, proceeds through structure prediction using multiple methods, incorporates rigorous quality filtering, and concludes with functional annotation and novelty assessment [1].

Analyzing Hidden Representations in Protein Language Models

Protein language models (PLMs) transform sequences into hidden representations that encode structural information. Recent research has focused on understanding the shape of these representations using mathematical approaches such as square-root velocity (SRV) representations and graph filtrations, which naturally lead to a metric space for comparing protein representations [3]. Analysis of different protein types from the SCOP dataset reveals that the Karcher mean and effective dimension of the SRV shape space follow a non-linear pattern as a function of the layers in ESM2 models of different sizes [3].

Graph filtrations serve as a tool to study the context lengths at which models encode structural features of proteins. Research indicates that PLMs preferentially encode immediate and local relations between residues, with performance degrading for larger context lengths [3]. Interestingly, the most structurally faithful encoding tends to occur close to, but before the last layer of the models, suggesting that training folding models on these intermediate layers might improve performance [3].

Visualization and Analysis of Sequence Space

Multiple tools enable the visualization and analysis of protein sequences in the context of their structural features:

AlignmentViewer provides web-based visualization of multiple sequence alignments with particular strengths in analyzing conservation patterns and the distribution of proteins in sequence space [5]. The tool employs UMAP (Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection) dimensionality reduction to represent sequence relationships in two or three-dimensional space, using the number of amino acid differences between pairs of sequences (Hamming distance) as the distance metric [5].

Sequence Coverage Visualizer (SCV) enables 3D visualization of protein sequence coverage using peptide lists identified from proteomics experiments [2]. This tool maps experimental data onto 3D structures, enabling researchers to visualize structural aspects of proteomics results, including post-translational modifications and limited proteolysis data [2].

The following workflow illustrates the process of sequence coverage visualization:

Diagram 2: Sequence Coverage Visualization Process (76 characters)

This workflow demonstrates how proteomics data can be transformed into structural insights through mapping peptide identifications onto 3D models, enabling visualization of structural features and experimental validation [2].

Experimental Protocols for Key Analyses

Protocol: Limited Proteolysis with 3D Visualization

Limited proteolysis coupled with 3D visualization provides insights into protein structural features and dynamics [2].

Materials:

- Native protein sample

- Sequence-grade protease (e.g., trypsin)

- Quenching solution (e.g., 1% formic acid)

- LC-MS/MS system

- SCV web application (http://scv.lab.gy) [2]

Procedure:

- Time-course digestion: Incubate native protein with protease at an enzyme-to-substrate ratio of 1:100 (w/w) at 25°C. Remove aliquots at various time points (e.g., 0, 1, 5, 15, 30, 60, 120 minutes).

- Reaction quenching: Add quenching solution to each aliquot immediately after collection.

- Peptide identification: Analyze quenched samples using LC-MS/MS with standard bottom-up proteomics parameters.

- Data processing: Identify peptides using database search software (e.g., MaxQuant, Proteome Discoverer).

- 3D visualization: Input the peptide lists with time point information into SCV. Use curly brackets with brackets "{}[group_name]" to designate different time points.

- Structural analysis: Observe the progression of digestion through time in the 3D viewer, identifying easily accessible regions (early time points) versus protected regions (later time points).

Interpretation: Regions digested at early time points correspond to flexible or surface-exposed regions, while protected regions may indicate structural stability, internal segments, or protein-protein interaction interfaces.

Protocol: Analyzing Local Sequence-Structure Relationships

This protocol enables the analysis of amino acid preferences for local structural environments [4].

Materials:

- Protein Data Bank (PDB) structures

- Local structure parameterization software

- Clustering algorithms (e.g., hierarchical clustering)

- Statistical analysis environment (e.g., R, Python)

Procedure:

- Dataset compilation: Compile a non-redundant set of high-resolution protein structures (e.g., ≤ 2.0 Å resolution, ≤ 20% sequence identity).

- Local structure parameterization: For each Cα atom, calculate the two angles θ and μ that define the local structural environment.

- Amino acid grouping: Perform hierarchical clustering of the 20 amino acids based on their similarity in local structural space using appropriate distance metrics.

- Propensity calculation: For each local structural bin, calculate amino acid propensities as P(aa|structure) = (nobserved / nexpected).

- Statistical validation: Apply statistical tests (e.g., chi-square) to identify significant deviations from random expectations.

- Scoring rubric development: Develop a scoring function that quantifies the compatibility between an amino acid and its local structural environment.

Interpretation: The resulting groupings and propensities reveal how different amino acids fit into specific local structures, providing insights into sequence design principles and local structural preferences.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Protein Sequence-Structure Analysis

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Application in Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| AlphaFold2 [1] [2] | Structure Prediction | High-accuracy protein structure prediction | Generating structural models for sequences without experimental structures |

| RoseTTAFold [2] | Structure Prediction | Protein structure prediction using deep learning | Alternative to AlphaFold2 for structure prediction |

| DMPfold [1] | Structure Prediction | Template-free protein structure prediction | Generating models for sequences with low homology to known structures |

| Rosetta [1] | Structure Prediction | de novo protein structure prediction | Generating structural models through physical principles |

| DeepFRI [1] | Functional Annotation | Structure-based function prediction | Providing residue-specific functional annotations for structural models |

| AlignmentViewer [5] | Sequence Analysis | Multiple sequence alignment visualization | Analyzing conservation patterns and sequence space distribution |

| Sequence Coverage Visualizer (SCV) [2] | Visualization | 3D visualization of sequence coverage | Mapping proteomics data onto protein structures |

| iCn3D [6] | Structure Visualization | Interactive 3D structure viewer | Exploring structure-function relationships |

| Graphviz [7] | Visualization | Graph visualization software | Creating diagrams of structural networks and relationships |

| Cytoscape [8] | Network Analysis | Complex network visualization and analysis | Integrating and visualizing structural and interaction data |

Future Directions and Applications in Drug Development

The mapping of the protein sequence universe has profound implications for drug development and therapeutic design. Understanding hidden representations in protein sequence space enables more accurate prediction of protein-ligand interactions, identification of allosteric sites, and design of targeted therapeutics. For drug development professionals, these approaches offer opportunities to identify novel drug targets, especially in under-explored regions of the protein universe such as microbial proteins [1].

The integration of structural information with functional annotations at residue resolution enables precision targeting of functional sites [1] [2]. As protein language models improve their ability to capture long-range interactions and structural features, they will become increasingly valuable for predicting functional consequences of sequence variations and designing proteins with novel functions [3]. The continuous nature of the structural space suggests that drug design efforts can focus on exploring the continuous landscape around known functional motifs rather than searching for disconnected islands of activity [1].

The combination of large-scale structure prediction, functional annotation, and advanced visualization represents a powerful framework for advancing our understanding of the protein sequence universe. As these methodologies mature, they will increasingly support rational drug design, mechanism of action studies, and the identification of novel therapeutic targets across diverse disease areas.

The exploration of protein sequence space is fundamentally governed by the methods used to represent these biological polymers computationally. The evolution from handcrafted features to deep learning embeddings represents a pivotal shift in computational biology, moving from explicit, human-defined descriptors to implicit, machine-discovered representations that capture complex biological constraints. This transition has unlocked the ability to model the hidden representations within protein sequences, revealing patterns and relationships that are not apparent from primary sequence alone. Framed within the broader thesis on hidden representations in protein sequence research, this evolution has transformed our capacity to predict function, structure, and interactions from sequence information alone. Where researchers once manually engineered features based on domain knowledge—such as physicochemical properties and evolutionary conservation—modern approaches leverage self-supervised learning on millions of sequences to derive contextual embeddings that encapsulate structural, functional, and evolutionary constraints [9] [10]. This technical guide examines the methodological progression, quantitative advancements, and practical implementations of these representation paradigms, providing researchers with the experimental protocols and analytical frameworks needed to navigate modern protein sequence analysis.

The Era of Handcrafted Features: Engineering Biological Domain Knowledge

Early computational approaches to protein sequence analysis relied exclusively on handcrafted features—explicit numerical representations designed by researchers to encode specific biochemical properties or evolutionary signals. These features served as the input for traditional machine learning classifiers such as support vector machines and random forests.

Principal Handcrafted Feature Types

The table below summarizes the major categories of handcrafted features used in traditional protein sequence analysis:

Table 1: Traditional Handcrafted Feature Types for Protein Sequence Representation

| Feature Category | Specific Examples | Biological Rationale | Typical Dimensionality |

|---|---|---|---|

| Amino Acid Composition | Composition, Transition, Distribution (CTD) | Encodes global sequence composition biases linked to structural class | 20-147 dimensions |

| Evolutionary Conservation | Position-Specific Scoring Matrix (PSSM) | Captures evolutionary constraints from multiple sequence alignments | L×20 (L = sequence length) |

| Physicochemical Properties | Hydrophobicity, charge, side-chain volume, polarity | Represents biophysical constraints affecting folding and interactions | Variable (3-500+ dimensions) |

| Structural Predictions | Secondary structure, solvent accessibility | Provides proxy for structural features when 3D structures unavailable | L×3 (secondary structure) |

| Sequence-Derived Metrics | k-mer frequencies, n-gram patterns | Captures local sequence motifs and patterns | 20^k for k-mers |

Limitations of Handcrafted Representations

While handcrafted features enabled early successes in protein classification and function prediction, they presented fundamental limitations. The feature engineering process was domain-specific, labor-intensive, and inherently incomplete—unable to capture the complex, interdependent constraints governing protein sequence-structure-function relationships [10] [11]. Each feature type captured only one facet of the multidimensional biological reality, and integrating these disparate representations often required careful weighting and normalization without clear biological justification. Furthermore, these representations typically lacked residue-level context, treating each position independently rather than capturing the complex contextual relationships that define protein folding and function.

The Deep Learning Revolution: Protein Embeddings as Learned Representations

The advent of deep learning transformed protein sequence representation through protein language models (pLMs) that learn contextual embeddings via self-supervised pre-training on millions of sequences. These models treat amino acid sequences as a "language of life," where residues constitute tokens and entire proteins form sentences [12] [13].

Architectural Foundations of Protein Language Models

Protein language models predominantly employ transformer architectures with self-attention mechanisms, trained using masked language modeling objectives on massive sequence databases such as UniRef50 [12] [11]. The self-attention mechanism enables these models to capture long-range dependencies and residue-residue interactions across entire protein sequences, effectively learning the grammatical rules and semantic relationships of the protein sequence language.

Prominent Protein Language Models and Their Specifications

The table below compares major protein language models used to generate state-of-the-art embeddings:

Table 2: Comparative Specifications of Prominent Protein Language Models

| Model Name | Architecture | Parameters | Training Data | Embedding Dimension | Key Capabilities |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ESM-2 [11] | Transformer | 650M to 15B | UniRef50 | 1280-5120 | State-of-the-art structure prediction, residue-level embeddings |

| ProtT5 [12] [10] | Transformer (T5) | ~3B | UniRef50 | 1024 | Superior performance on per-residue tasks |

| ProtBERT [9] [13] | Transformer (BERT) | ~420M | BFD, UniRef100 | 1024 | Bidirectional context, functional prediction |

| ProstT5 [12] | Transformer + Structural Tokens | ~3B | UniRef50 + 3Di tokens | 1024 | Integrated sequential and structural information |

Experimental Protocols: From Embedding Generation to Biological Application

Protocol 1: Generating Residue-Level Embeddings for Sequence Analysis

This protocol outlines the standard methodology for extracting residue-level embeddings from protein language models, as employed in recent studies [12] [11]:

Sequence Preparation: Input protein sequences in standard amino acid notation (20 canonical residues). Sequences shorter than the model's context window can be used directly; longer sequences may require strategic truncation or segmentation.

Tokenization: Convert amino acid sequences to token indices using the model-specific tokenizer. Most pLMs treat each amino acid as a separate token, with special tokens for sequence start/end and masking.

Embedding Extraction:

- Pass tokenized sequences through the pre-trained model

- Extract hidden representations from the final transformer layer (or specified intermediate layers)

- For ProtT5 and ESM-2, this generates a 2D matrix of dimensions [sequencelength × embeddingdimension]

Embedding Normalization (Optional): Apply layer normalization or Z-score normalization to standardize embeddings across different sequences and models.

Downstream Application: Utilize embeddings for specific tasks such as:

Protocol 2: Embedding-Based Protein Sequence Alignment

Recent research has demonstrated that embedding-based alignment significantly outperforms traditional methods for detecting remote homology in the "twilight zone" (20-35% sequence similarity) [12]. The following protocol details this process:

Embedding Generation: Generate residue-level embeddings for both query and target sequences using models such as ProtT5 or ESM-2.

Similarity Matrix Construction: Compute a residue-residue similarity matrix SM(u×v) where each entry SM(a,b) represents the similarity between residue a in sequence P and residue b in sequence Q, calculated as: SM(a,b) = exp(-δ(pa, qb)) where δ denotes Euclidean distance between residue embeddings pa and qb [12].

Z-score Normalization: Reduce noise in the similarity matrix by applying row-wise and column-wise Z-score normalization:

- Compute row-wise mean μr(a) and standard deviation σr(a) for each residue a ∈ P

- Compute column-wise mean μc(b) and standard deviation σc(b) for each residue b ∈ Q

- Calculate normalized matrix SM' with elements SM'(a,b) = [Zr(a,b) + Zc(a,b)] / 2

Refinement with K-means Clustering: Apply K-means clustering to group similar residue embeddings, then refine the similarity matrix based on cluster assignments.

Double Dynamic Programming: Perform alignment using a two-level dynamic programming approach that first identifies high-similarity regions then constructs the global alignment.

Statistical Validation: Validate alignment quality against known structural alignments using metrics like TM-score [12].

Visualization: Workflow for Embedding-Based Protein Sequence Analysis

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow for protein sequence analysis using deep learning embeddings:

Quantitative Comparison: Handcrafted Features vs. Deep Learning Embeddings

Rigorous benchmarking studies have quantitatively demonstrated the superiority of embedding-based approaches across multiple protein informatics tasks. The following table summarizes performance comparisons reported in recent literature:

Table 3: Performance Comparison of Representation Approaches Across Protein Informatics Tasks

| Task | Best Handcrafted Feature Performance | Best Embedding-Based Performance | Performance Gain | Key Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Remote Homology Detection (Twilight Zone) | ~0.45-0.55 Spearman correlation with structural similarity | ~0.65-0.75 Spearman correlation with TM-score [12] | +35-45% | Scientific Reports (2025) [12] |

| Protein-Protein Interface Prediction | MCC: 0.249 (PIPENN with handcrafted features) | MCC: 0.313 (PIPENN-EMB with ProtT5 embeddings) [10] | +25.7% | Scientific Reports (2025) [10] |

| Protein-DNA Binding Site Prediction | AUROC: ~0.78-0.82 (PSSM-based methods) | AUROC: 0.85-0.88 (ESM-2 with SECP network) [11] | +8-12% | BMC Genomics (2025) [11] |

| Functional Group Classification | Accuracy: ~82-86% (k-mer + PSSM features) | Accuracy: 91.8% (CNN with embeddings) [9] | +7-12% | arXiv (2025) [9] |

Ablation Studies: Feature Contribution Analysis

Recent ablation studies have systematically quantified the relative contribution of different feature types to predictive performance. In protein-protein interface prediction, ProtT5 embeddings alone achieved performance comparable to comprehensive handcrafted feature sets, and their combination with structural information yielded the best results [10]. Similarly, for protein-DNA binding site prediction, the fusion of ESM-2 embeddings with evolutionary features (PSSM) through multi-head attention mechanisms demonstrated synergistic effects, outperforming either feature type in isolation [11].

Implementing embedding-based protein sequence analysis requires specific computational resources and software tools. The following table details essential components of the modern computational biologist's toolkit:

Table 4: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Protein Embedding Applications

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Resources | Primary Function | Access Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-trained Models | ESM-2, ProtT5, ProtBERT | Generate protein sequence embeddings without training | HuggingFace, GitHub repositories |

| Embedding Extraction Libraries | BioPython, Transformers, ESMPython | Python interfaces for loading models and processing sequences | PyPI, Conda packages |

| Specialized Prediction Tools | PIPENN-EMB [10], ESM-SECP [11] | Domain-specific predictors leveraging embeddings | GitHub, web servers |

| Benchmark Datasets | PISCES [12], TE46/TE129 [11], BIODLTE [10] | Standardized datasets for method evaluation | Public repositories (URLs in citations) |

| Sequence Databases | UniRef50 [12], Swiss-Prot [11] | Curated protein sequences for training and analysis | UniProt, FTP downloads |

| Validation Tools | TM-align [12], HOMSTRAD | Structural alignment for method validation | Standalone packages, web services |

Future Directions: Multi-Modal Integration and Explainable AI

The evolution of protein sequence representation continues toward multi-modal integration and enhanced interpretability. Emerging approaches like SSEmb combine sequence embeddings with structural information in joint representation spaces, creating models that maintain robust performance even when sequence information is scarce [14]. Similarly, the integration of explainable AI (XAI) techniques—such as Grad-CAM and Integrated Gradients—with embedding-based models enables researchers to interpret predictions and identify biologically meaningful motifs [9]. These approaches help bridge the gap between predictive accuracy and biological insight, revealing the residue-level determinants of model decisions and validating that learned representations align with known biochemical principles. As protein language models continue to evolve, their capacity to capture the complex constraints governing protein sequence space will further transform our ability to decipher the hidden representations underlying protein structure, function, and evolution.

Protein Language Models (PLMs) represent a revolutionary advancement in computational biology, applying transformer-based neural architectures to learn complex patterns from billions of unlabeled amino acid sequences. By training on evolutionary-scale datasets, these models develop rich internal representations that capture fundamental biological principles without explicit supervision. This technical guide examines the mechanistic foundations of PLMs, exploring how they distill evolutionary and structural biases into predictive frameworks for protein engineering and drug development. Framed within broader research on hidden representations in protein sequence space, we analyze how PLMs encode information across multiple biological scales—from local amino acid interactions to global tertiary structures—enabling accurate prediction of protein function, stability, and mutational effects without requiring experimentally determined structures.

Core Architecture and Pre-training Objectives

Transformer Architecture Adapted for Protein Sequences

Protein language models build upon the transformer architecture, specifically the encoder-only configuration used in models like BERT. The ESM-2 model series implements key modifications including Rotary Position Embedding (RoPE), which enables extrapolation beyond trained context windows by incorporating relative positional information directly into the attention mechanism [15]. The self-attention operation transforms input token features X into query (Q), key (K), and value (V) matrices through learned linear projections:

The scaled dot-product attention computes contextualized representations:

Multiple attention heads operate in parallel, capturing diverse relationship patterns within protein sequences [15]. The ESM-2 architecture stacks these transformer blocks with feed-forward networks and residual connections, creating deep networks (up to 15B parameters in largest configurations) that progressively abstract sequence information across layers [15].

Masked Language Modeling Pre-training

PLMs learn biological constraints through self-supervised pre-training on massive sequence corpora like UniRef, containing hundreds of millions of diverse protein sequences. The primary training objective is masked language modeling (MLM), which randomly masks portions of input sequences and trains the model to predict the original amino acids from contextual evidence [15]. Formally, the objective minimizes:

where M represents the masked positions in sequence x [15]. Through this denoising objective, PLMs internalize evolutionary constraints, physicochemical properties, and structural patterns that characterize functional proteins, effectively learning the "grammar" of protein sequences.

Table 1: Key Protein Language Model Architectures and Training Scales

| Model | Parameters | Training Sequences | Key Innovations | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ESM-2 | 8M to 15B | ~65M distinct sequences from UniRef50 | Rotary Position Embedding, architectural enhancements | Structure prediction, function annotation |

| METL | Not specified | 20-30M synthetic variants | Biophysical pretraining with Rosetta simulations | Protein engineering, thermostability prediction |

| Protein Structure Transformer (PST) | Based on ESM-2 | 542K protein structures | Lightweight structural adapters integrated into self-attention | Function prediction with structural awareness |

Learning Evolutionary Biases from Sequence Statistics

Capturing Coevolutionary Signals

PLMs implicitly detect patterns of coevolution—where mutations at one position correlate with changes at distal sites—through their attention mechanisms. This capability emerges naturally during pre-training as the model learns to reconstruct masked tokens based on global sequence context. Research demonstrates that the attention heads in later layers of models like ESM-2 specifically encode residue-residue contact maps, effectively identifying tertiary structural contacts from sequence information alone [16]. This explains why PLMs serve as excellent feature extractors for downstream structure prediction tasks like those in ESMFold.

Multi-scale Hierarchical Representations

As information propagates through the transformer layers, PLMs build increasingly abstract representations of protein sequences. Early layers typically capture local amino acid properties and biochemical features like charge and hydrophobicity. Intermediate layers identify secondary structure elements and conserved motifs, while deeper layers encode tertiary interactions and global structural features [3] [16]. This hierarchical organization mirrors the structural hierarchy of proteins themselves, enabling the model to reason across multiple biological scales when making predictions.

Incorporating Structural Biases

Explicit Structure Integration Methods

Recent advances focus on enhancing PLMs with explicit structural information to complement evolutionarily-learned biases. The Protein Structure Transformer (PST) implements a lightweight framework that integrates structural extractors directly into the self-attention blocks of pre-trained transformers like ESM-2 [15]. This approach fuses geometric structure representations with sequential context without requiring extensive retraining, demonstrating that joint sequence-structure embeddings consistently outperform sequence-only models while maintaining computational efficiency [15].

PST achieves remarkable parameter efficiency, requiring pretraining on only 542K protein structures—approximately three orders of magnitude less data than used to train base PLMs—while matching or exceeding the performance of more complex structure-based methods [15]. The model refines only the structure extractors while keeping the backbone transformer frozen, addressing parameter efficiency concerns that have limited previous structure-integration attempts.

Biophysics-Informed Pretraining

The METL framework introduces an alternative approach by pretraining transformers on biophysical simulation data rather than evolutionary sequences [17]. Using Rosetta molecular modeling, METL generates synthetic data for millions of protein variants, computing 55 biophysical attributes including molecular surface areas, solvation energies, van der Waals interactions, and hydrogen bonding networks [17]. The model learns to predict these attributes from sequence, building a biophysically-grounded representation that complements evolutionarily-learned patterns.

METL implements two specialization strategies: METL-Local, which learns representations targeted to specific proteins of interest, and METL-Global, which captures broader sequence-structure relationships across diverse protein families [17]. This biophysics-based approach demonstrates particular strength in low-data regimes and extrapolation tasks, successfully designing functional green fluorescent protein variants with only 64 training examples [17].

Table 2: Structural Integration Methods in Protein Language Models

| Method | Integration Approach | Structural Data Source | Training Efficiency | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protein Structure Transformer (PST) | Structural adapters in self-attention blocks | AlphaFold DB, PDB structures | 542K structures, frozen backbone PLM | Parameter efficiency, maintains sequence understanding |

| METL Biophysical Pretraining | Learn mapping from sequence to biophysical attributes | Rosetta-generated structural models | 20-30M synthetic variants | Strong generalization from small datasets |

| Sparse Autoencoder Interpretation | Post-hoc analysis of structural features | Model activations from ESM2-3B | No retraining required | Identifies structural features learned implicitly |

Interpretability and Representation Analysis

Sparse Autoencoders for Mechanistic Interpretability

Understanding how PLMs transform sequences into structural predictions remains a significant challenge. Sparse autoencoders (SAEs) have emerged as a powerful tool for interpreting these black-box models by learning linear representations in high-dimensional spaces [16]. When applied to large PLMs like ESM2-3B (the backbone of ESMFold), SAEs decompose activations into interpretable features corresponding to biological concepts [16].

Matryoshka SAEs further enhance this approach by learning nested hierarchical representations through embedded feature groups of increasing dimensionality [16]. This architecture naturally captures proteins' multi-scale organization—from local amino acid patterns to global structural motifs—enabling researchers to trace how sequence information propagates through abstraction levels to inform structural predictions.

Feature Steering and Control

Interpretability methods now enable targeted manipulation of PLM representations to control structural properties. By identifying SAE features correlated with specific structural attributes (like solvent accessibility), researchers can steer model predictions by artificially activating these features while maintaining the input sequence [16]. This demonstrates a causal relationship between discovered features and structural outcomes, validating interpretability methods while enabling potential protein design applications.

The following diagram illustrates the sparse autoencoder framework for interpreting protein structure prediction:

SAE Interpretation of Structure Prediction

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Joint Sequence-Structure Embedding

The Protein Structure Transformer methodology demonstrates how to effectively integrate structural information into pre-trained PLMs [15]:

- Base Model Preparation: Start with a pre-trained ESM-2 model as the foundational architecture.

- Graph Representation: Convert protein structures into graph representations where nodes represent amino acids and edges capture spatial relationships.

- Structural Adapter Integration: Insert lightweight structural adapter modules into the self-attention blocks of the transformer. These adapters fuse geometric information without disrupting pre-trained sequence representations.

- Masked Language Modeling Fine-tuning: Continue training with the MLM objective on a curated set of 542K protein structures, keeping the base transformer frozen while updating only the structural adapters.

- Evaluation: Assess performance on downstream tasks including enzyme commission number prediction, Gene Ontology term prediction, and ProteinShake benchmarks.

This approach achieves parameter efficiency by leveraging pre-trained sequence knowledge while adding minimal specialized parameters for structural processing [15].

Biophysical Pretraining Protocol

The METL framework implements biophysics-based pretraining through these methodological steps [17]:

Synthetic Data Generation:

- Select base proteins (148 diverse structures for METL-Global or single protein for METL-Local)

- Generate sequence variants with up to five random amino acid substitutions

- Model variant structures using Rosetta molecular modeling

- Compute 55 biophysical attributes for each modeled structure

Transformer Pretraining:

- Initialize transformer encoder with structure-based relative positional embeddings

- Train model to predict biophysical attributes from sequence alone

- Use mean squared error loss between predicted and computed attributes

Experimental Fine-tuning:

- Transfer pretrained weights to task-specific models

- Fine-tune on experimental sequence-function data

- Evaluate generalization through train-test splits that test mutation extrapolation, position extrapolation, and regime extrapolation

This protocol produces models that excel in low-data protein engineering scenarios, successfully designing functional GFP variants with only 64 training examples [17].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Computational Tools for Protein Language Model Research

| Tool/Resource | Type | Function | Access |

|---|---|---|---|

| ESM-2/ESM-3 Model Series | Pre-trained PLM | Base model for sequence representation and structure prediction | https://github.com/facebookresearch/esm |

| Rosetta Molecular Modeling Suite | Structure Prediction | Generate biophysical attributes for pretraining | https://www.rosettacommons.org/ |

| Protein Structure Transformer (PST) | Hybrid Sequence-Structure Model | Joint embeddings with computational efficiency | https://github.com/BorgwardtLab/PST |

| Sparse Autoencoder Framework | Interpretability Tool | Mechanistic interpretation of structure prediction | https://github.com/reticularai/interpretable-protein-sae |

| AlphaFold Database | Structure Repository | Source of high-confidence structures for training | https://alphafold.ebi.ac.uk/ |

| UniProt/UniRef Databases | Sequence Databases | Evolutionary-scale sequence data for pretraining | https://www.uniprot.org/ |

Protein language models have fundamentally transformed computational biology by learning evolutionary and structural biases directly from unlabeled sequence data. Through transformer architectures adapted for amino acid sequences, masked language modeling objectives, and innovative structural integration methods, PLMs capture the fundamental principles governing protein sequence-structure-function relationships. The emerging toolkit for interpreting these models—particularly sparse autoencoders scaled to billion-parameter networks—provides unprecedented visibility into how biological knowledge is represented and processed. As PLMs continue evolving with better structural awareness and biophysical grounding, they offer accelerating returns for protein engineering, therapeutic design, and fundamental biological discovery. The ongoing research into hidden representations within protein sequence space promises to further bridge the gap between evolutionary statistics and physical principles, enabling more precise control and design of protein functions.

The advent of protein language models (pLMs) has revolutionized computational biology by generating high-dimensional representations, or embeddings, that capture complex evolutionary and functional information from protein sequences. However, interpreting these hidden representations remains a significant challenge. This whitepaper examines ProtSpace, an open-source tool specifically designed to visualize and explore these high-dimensional protein embeddings in two and three dimensions. By enabling researchers to project complex embedding spaces into intuitive visual formats, ProtSpace facilitates the discovery of functional patterns, evolutionary relationships, and structural insights that are readily missed by traditional sequence analysis methods. Framed within broader research on hidden representations in protein sequence space, this technical guide provides detailed methodologies, experimental protocols, and practical applications of ProtSpace for scientific research and drug development.

Protein language models, inspired by breakthroughs in natural language processing, transform protein sequences into numerical vectors in high-dimensional space. These embeddings capture intricate relationships between sequences, encapsulating information about structural properties, evolutionary conservation, and functional characteristics. While powerful, this representation format creates a fundamental interpretation barrier for researchers. The inability to directly perceive relationships in hundreds or thousands of dimensions limits hypothesis generation and scientific discovery.

ProtSpace addresses this challenge by implementing dimensionality reduction techniques that project high-dimensional embeddings into 2D or 3D spaces while preserving significant topological relationships. This capability allows researchers to visually identify clusters of functionally similar proteins, trace evolutionary pathways, and detect outliers that may represent novel functions. By making the invisible landscape of protein embeddings visually accessible, ProtSpace serves as a critical bridge between raw computational outputs and biological insight, particularly in the context of drug target identification and protein engineering.

ProtSpace: Technical Architecture and Core Functionality

ProtSpace is implemented as both a pip-installable Python package and an interactive web interface, making it accessible for users with varying computational expertise [18] [19]. Its architecture integrates multiple components for comprehensive protein space visualization alongside structural correlation.

Core Visualization Engine

At the heart of ProtSpace is its ability to transform high-dimensional protein embeddings into visually interpretable layouts through established dimensionality reduction algorithms:

- UMAP (Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection): Effectively preserves both local and global data structure, ideal for identifying fine-grained functional clusters

- t-SNE (t-Distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding): Emphasizes local similarities and cluster separation

- PCA (Principal Component Analysis): Identifies dominant axes of variation in the embedding space

- MDS (Multidimensional Scaling): Preserves pairwise distances between protein embeddings

The tool accepts input directly from popular pLMs including ESM2, ProtBERT, and AlphaFold [3], supporting both pre-computed embeddings and raw sequences for on-the-fly embedding generation.

Interactive Exploration Capabilities

ProtSpace provides more than static visualization through several interactive features that facilitate deep exploration:

- Dynamic Filtering: Select and highlight proteins based on metadata annotations (e.g., taxonomic origin, functional class)

- Cross-Highlighting: Integration between 2D/3D embedding views and protein structure visualization

- Session Portability: Complete analysis sessions can be saved and shared via JSON files [20], enabling collaborative research and reproducible workflows

- Custom Coloring: Color-code proteins based on various features including sequence similarity, structural properties, or functional annotations

Table 1: Core Technical Specifications of ProtSpace

| Component | Implementation | Supported Formats | Key Capabilities |

|---|---|---|---|

| Visualization Engine | Python (Plotly, Matplotlib) | UMAP, t-SNE, PCA, MDS | 2D scatter, 3D scatter, interactive plots |

| Data Input | FASTA parser, embedding loaders | FASTA, CSV, JSON, PyTorch | Sequence input, pre-computed embeddings |

| Structure Integration | 3Dmol.js, Mol* | PDB, mmCIF | Surface representation, residue highlighting |

| Export Options | SVG, PNG, JSON | Session files, publication figures | Reproducible research, collaborative analysis |

Methodological Framework: Experimental Protocols for Protein Space Exploration

Implementing ProtSpace effectively requires systematic experimental design. The following protocols outline standardized methodologies for key research scenarios.

Protocol 1: Functional Cluster Identification in Metagenomic Data

Objective: Identify novel functional clusters in large-scale metagenomic protein datasets.

Materials and Reagents:

- Protein sequences (FASTA format)

- ProtSpace Python package

- Reference database (e.g., UniRef90)

- Compute resources (minimum 8GB RAM for datasets <100,000 sequences)

Procedure:

- Embedding Generation: Process protein sequences through ESM2 model (650M parameters) to generate 1280-dimensional embeddings

- Similarity Matrix Computation: Calculate pairwise cosine similarity between all embeddings

- Dimensionality Reduction: Apply UMAP with parameters (nneighbors=15, mindist=0.1, metric='cosine')

- Interactive Visualization: Load projection into ProtSpace web interface

- Cluster Annotation: Color points by taxonomic origin and known functions

- Outlier Detection: Identify sequences distant from known functional clusters

- Structural Correlation: Map emergent clusters to available 3D structures

Interpretation: Functional clusters appear as dense regions in the projection, while outliers may represent novel functions. Cross-referencing with taxonomic metadata helps distinguish horizontal gene transfer events from evolutionary divergence.

Protocol 2: Evolutionary Relationship Mapping in Protein Superfamilies

Objective: Trace evolutionary relationships within large protein superfamilies using representation-based hierarchical clustering [21].

Materials and Reagents:

- Superfamily sequences (e.g., FMN/F420-binding split barrel superfamily)

- HMM profiles (Pfam, InterPro)

- Multiple sequence alignment tool (MAFFT, ClustalΩ)

- Phylogenetic analysis software (IQ-TREE, RAxML)

Procedure:

- Sequence Curation: Collect diverse representatives from the superfamily (≥1,000 sequences)

- Embedding Generation: Compute pLM embeddings for all sequences

- Hierarchical Clustering: Apply agglomerative clustering to embeddings (average linkage, cosine distance)

- Comparative Analysis: Compare embedding-based clustering with traditional BLAST-based sequence similarity networks

- Dimensionality Reduction: Project entire superfamily using ProtSpace with MDS for distance preservation

- Functional Mapping: Annotate clusters with experimental functional data

- Phylogenetic Validation: Compare with phylogenetic trees derived from structure-based alignment

Interpretation: Representation-based clustering often reveals functional subcategories that sequence similarity alone misses, particularly for distant homologs with conserved functions but divergent sequences.

Case Studies: Research Applications and Findings

Phage Protein Functional Landscape Analysis

In an analysis of phage-encoded proteins, ProtSpace revealed distinct clusters corresponding to major functional groups including DNA polymerases, capsid proteins, and lytic enzymes [20]. The visualization also identified a mixed region containing proteins of unknown function, suggesting these might represent generalist modules with context-dependent functions or potentially bias in the training data of current pLMs. This insight guides targeted experimental characterization of these ambiguous regions to expand functional annotation databases.

Venom Toxin Evolution and Classification

ProtSpace analysis of venom proteins from diverse organisms revealed unexpected convergent evolution between scorpion and snake toxins [20]. The embedding visualization showed these evolutionarily distinct toxins clustering together based on functional similarity rather than taxonomic origin, challenging existing toxin family classifications. This finding provided evidence refuting the aculeatoxin family hypothesis and demonstrated how pLM embeddings capture functional constraints that transcend evolutionary lineage.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Protein Embedding Visualization

| Reagent/Resource | Function/Purpose | Implementation in ProtSpace |

|---|---|---|

| Protein Language Models (ESM2, ProtBERT) | Generate embeddings from sequences | Direct integration for embedding generation |

| Sequence Similarity Networks | Traditional homology comparison | Comparative analysis with embedding approaches |

| Hidden Markov Models (HMMs) | Profile-based family identification | Unbiased representative sampling [21] |

| Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BALT) | Sequence homology baseline | Benchmark for embedding-based clustering [21] |

| Protein Data Bank (PDB) | 3D structure reference | Structure-function correlation in visualization |

| Hierarchical Clustering | Relationship analysis at multiple scales | Capturing full range of homologies [21] |

| Session JSON Files | Research reproducibility | Save/restore complete analysis state [20] |

Visualizing Experimental Workflows

The following diagram illustrates the core computational workflow for protein embedding visualization using ProtSpace, showing the integration between sequence inputs, computational transformations, and interactive exploration:

ProtSpace represents a significant advancement in making the hidden representations of protein language models accessible to researchers. By providing intuitive visualization of high-dimensional embedding spaces, it enables discovery of functional patterns, evolutionary relationships, and structural correlations that advance both basic science and applied drug development. As protein language models continue to evolve in scale and sophistication, tools like ProtSpace will play an increasingly critical role in extracting biologically meaningful insights from these powerful computational representations. Future development directions include integration with geometric deep learning for joint sequence-structure embedding visualization and real-time collaboration features for distributed research teams, further enhancing our ability to visualize and understand the invisible landscape of protein sequence space.

From Theory to Therapy: Methodological Advances and Applications in Drug Discovery and Protein Design

The endeavor to decipher the hidden representations within protein sequence space is a cornerstone of modern computational biology. Proteins, as the fundamental executors of biological function, encode their characteristics and capabilities within their amino acid sequences. However, the mapping from this one-dimensional sequence to a protein's complex three-dimensional structure and, ultimately, its biological function is profoundly complex and non-linear. Protein Representation Learning (PRL) has emerged as a transformative approach to tackle this challenge, aiming to distill high-dimensional, complex protein data into compact, informative computational embeddings that capture essential biological patterns [22] [23]. These learned representations serve as a critical substrate for a wide array of downstream tasks, including protein property prediction, function annotation, and de novo design, thereby accelerating research in molecular biology, medical science, and drug discovery [22].

The evolution of representation learning methodologies reflects a journey from leveraging hand-crafted features to employing sophisticated deep learning models that learn directly from data. This progression can be broadly taxonomized into feature-based, sequence-based, and multimodal approaches, each with distinct capabilities for uncovering the hidden information within protein sequences. This review provides a systematic examination of these three paradigms, framing them within the broader thesis of extracting meaningful, hierarchical representations from the raw language of amino acid sequences to power the next generation of biological insights and therapeutic innovations.

Feature-Based Representation Learning

Feature-based methods represent the foundational stage of protein representation learning. These approaches rely on predefined biochemical, structural, or statistical properties to transform protein sequences into structured numerical vectors [24] [23]. They have historically enabled numerous machine learning applications in computational biology, from protein classification to the prediction of subcellular localization and molecular interactions.

Core Methodologies and Descriptors

Feature-based approaches can be categorized based on the type of information they encode. The following table summarizes the primary classes of these descriptors, their core applications, and their inherent advantages and limitations [24] [23].

Table 1: Taxonomy of Feature-Based Protein Representation Methods

| Method Category | Core Applications | Key Examples | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Composition-Based | Genome assembly, sequence classification | AAC, DPC, TPC [24] | Computationally efficient, captures local patterns | High dimensionality, ignores sequence order |

| Sequence-Order | Protein function prediction, subcellular localization | PseAAC, CTD [24] [23] | Encodes residue order, incorporates physicochemical properties | Can be sensitive to parameter selection |

| Evolutionary | Protein structure/function prediction, PPI prediction | PSSM [23] | Leverages evolutionary conservation, robust feature extraction | Dependent on alignment quality and database size |

| Physicochemical | Protein annotation, protein-protein interaction prediction | AAIndex, Z-scales [23] | Biologically interpretable, encodes fundamental properties | Requires selection of relevant properties, can lack context |

The implementation of these descriptors has been greatly facilitated by unified software toolkits such as iFeature and PyBioMed, which provide comprehensive implementations of these encoding schemes alongside feature selection and dimensionality reduction utilities [23].

Experimental Protocol for Feature-Based Prediction

A typical workflow for building a predictive model using feature-based representations, as exemplified by the CAPs-LGBM channel protein predictor [25], involves several key stages:

- Dataset Construction: A benchmark dataset is curated, often from public databases like UniProt and Pfam. Sequences are rigorously filtered to remove redundancy (e.g., using CD-HIT with a 0.8 threshold) and split into training and testing sets.

- Feature Representation Learning: Multiple feature coding methods (e.g., 17 different descriptors encompassing composition, physicochemical, and sequence-order categories) are applied to the protein sequences to construct a large initial feature pool.

- Feature Optimization: A two-step feature selection strategy is employed to reduce dimensionality and mitigate redundancy. This involves evaluating the predictive power of individual features and their combinations to arrive at an optimal, compact feature vector (e.g., 16 dimensions in CAPs-LGBM).

- Model Training and Evaluation: A machine learning classifier (e.g., Light Gradient Boosting Machine - LGBM) is trained on the optimized feature set. The model's performance is then validated on the held-out test set using metrics such as accuracy and area under the precision-recall curve.

Despite their utility, feature-based methods have significant limitations. Their hand-crafted nature requires domain expertise for feature selection and struggles to capture long-range, contextual dependencies within a sequence [23]. This paved the way for more advanced, data-driven sequence-based approaches.

Sequence-Based Representation Learning

Sequence-based methods treat protein sequences as a "biological language," where the order and context of amino acids carry implicit rules and patterns. Inspired by advances in Natural Language Processing (NLP), these models learn statistical representations directly from large-scale sequence data, mapping proteins into a latent space where geometrical relationships reflect biological similarity [23].

From Language Models to Learned Representations

These approaches largely fall into two categories: non-aligned and aligned methods. Non-aligned methods, such as Protein Language Models (PLMs) like ESM-2, learn by training on millions of diverse protein sequences using objectives like masked language modeling, where the model must predict randomly obscured amino acids in a sequence based on their context [26]. This process forces the model to internalize the underlying biochemical "grammar," resulting in rich, contextual embeddings for each residue and the entire sequence.

Aligned methods, in contrast, leverage evolutionary information by analyzing Multiple Sequence Alignments (MSAs) of homologous proteins [23]. The core insight is that evolutionarily conserved residues are often critical for function and structure. By modeling co-evolutionary patterns, these methods capture structural and functional constraints, providing a powerful signal for tasks like protein structure prediction, as famously demonstrated by AlphaFold2 [23].

Critical Design Choices for Effective Representations

The transition from local residue embeddings to a global protein representation is a critical design choice. A systematic study highlighted that common practices can be suboptimal [27]. For instance, fine-tuning a pre-trained embedding model on a specific downstream task often leads to overfitting, especially when labeled data is limited. The recommended default is to keep the embedding model fixed during task-specific training.

Furthermore, constructing a global representation by simply averaging local representations (e.g., from a PLM) is less effective than learning an aggregation. The "Bottleneck" strategy, which uses an autoencoder to force the sequence through a low-dimensional latent representation during pre-training, has been shown to significantly outperform averaging, as it actively encourages the model to discover a compressed, global structure [27].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Global Representation Aggregation Strategies

| Aggregation Strategy | Description | Reported Impact on Downstream Task Performance |

|---|---|---|

| Averaging | Uniform or attention-weighted average of residue embeddings | Suboptimal performance; baseline for comparison [27] |

| Concatenation | Concatenating all residue embeddings (with dimensionality reduction) | Better than averaging, preserves more information [27] |

| Bottleneck (Autoencoder) | Learning a global representation via a pre-training reconstruction objective | Clearly outperforms other strategies; learns optimal aggregation [27] |

Multimodal Representation Learning

Proteins are more than just linear sequences; their function arises from an intricate interplay between sequence, three-dimensional structure, and functional annotations. Multimodal representation learning seeks to create a unified representation by integrating these heterogeneous data sources, addressing the limitation of methods that rely on a single modality [28] [29] [26].

Frameworks for Data Integration

Multimodal frameworks like MASSA and DAMPE represent the cutting edge in this domain [29] [28]. The MASSA framework, for example, integrates approximately one million data points across sequences, structures, and Gene Ontology (GO) annotations. Its architecture employs a hierarchical two-step alignment: first, token-level self-attention aligns sequence and structure embeddings, and then a cross-transformer decoder globally aligns this combined representation with GO annotation embeddings [29]. This model is pre-trained using a multi-task loss function on five protein-specific objectives, including masked amino acid/GO prediction and domain/motif/region placement capture.

The DAMPE framework tackles two key challenges: cross-modal distributional mismatch and noisy extrinsic relational data [28]. It uses Optimal Transport (OT) to align intrinsic embedding spaces from different modalities, effectively mitigating heterogeneity. For integrating noisy protein-protein interaction graphs, it employs a Conditional Graph Generation (CGG) method, where a condition encoder fuses aligned intrinsic embeddings to guide graph reconstruction, thereby absorbing graph-aware knowledge into the protein representations.

Experimental Workflow for Multimodal Pre-training

The following diagram illustrates the generalized experimental workflow for a multimodal protein representation learning framework, synthesizing elements from MASSA [29] and joint sequence-structure studies [26].

The development and evaluation of protein representation learning models rely on a curated set of public databases and software tools. The following table details key resources that constitute the essential toolkit for researchers in this field.

Table 3: Essential Research Resources for Protein Representation Learning

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function | Relevance to Representation Learning |

|---|---|---|---|

| UniProt [29] [25] | Database | Comprehensive repository of protein sequence and functional information. | Primary source for sequence and annotation data for pre-training and benchmark creation. |

| RCSB PDB [29] | Database | Curated database of experimentally determined 3D protein structures. | Source of high-quality structural data for structure-based and multimodal models. |

| AlphaFold DB [29] | Database | Database of protein structure predictions from the AlphaFold system. | Provides high-accuracy structural data for proteins with unknown experimental structures. |

| Pfam [27] [25] | Database | Collection of protein families and multiple sequence alignments. | Source for homologous sequences and MSAs for aligned methods and dataset construction. |

| Gene Ontology (GO) [29] | Database/Taxonomy | Structured, controlled vocabulary for protein functions. | Provides functional annotation labels for pre-training objectives and model evaluation. |

| iFeature [23] | Software Toolkit | Unified platform for generating feature-based descriptors. | Facilitates extraction and analysis of hand-crafted feature representations. |

| ESM-2/ESM-3 [29] [26] | Software Model | State-of-the-art Protein Language Model (PLM). | Provides powerful pre-trained sequence embeddings for transfer learning and multimodal fusion. |

The journey to uncover hidden representations in protein sequence space has evolved through distinct yet interconnected paradigms. Feature-based methods provide a biologically interpretable foundation, sequence-based language models capture deep contextual and evolutionary signals, and multimodal frameworks strive for a holistic integration of sequence, structure, and function. The collective advancement of these approaches has fundamentally enhanced our ability to computationally reason about proteins, translating their raw sequences into powerful embeddings that drive progress in protein function prediction, engineering, and drug discovery. As the field moves forward, key challenges such as improving model interpretability, enhancing generalization across protein families, and efficiently scaling to ever-larger datasets will guide the next generation of protein representation learning methods.

The identification of novel drug-target relationships represents a critical pathway for accelerating drug development, particularly through drug repurposing. This technical guide frames this pursuit within a broader thesis on hidden representations in protein sequence space research. The fundamental premise is that the functional and biophysical properties of proteins are encoded within their primary amino acid sequences, creating a "sequence space" where distances between points correlate with functional relationships. By mapping this space and quantifying sequence distances, researchers can predict novel drug-target interactions (DTIs) that transcend traditional family-based classifications, enabling the discovery of repurposing opportunities for existing drugs.

Traditional drug discovery approaches face significant challenges, including high costs, lengthy development cycles, and high failure rates. Drug repurposing offers a strategic alternative by finding new therapeutic applications for existing drugs, potentially reducing development timelines and costs. Sequence-based methods have emerged as particularly valuable for this endeavor because protein sequence information is more readily available than three-dimensional structural data. As research reveals, these methods can predict interactions based solely on protein sequence and drug information, making them applicable to proteins with unknown structures [30]. The integration of advanced computational techniques, including deep learning and evolutionary scale modeling, is now enabling researchers to extract increasingly sophisticated representations from sequence data, uncovering relationships that were previously obscured in the complex topology of biological sequence space.

Theoretical Foundations: From Sequence to Function

The Biological Basis of Sequence-Function Relationships

The relationship between protein sequence and function is governed by evolutionary conservation and structural constraints. Proteins sharing evolutionary ancestry often maintain similar structural folds and functional capabilities, creating a foundation for predicting function from sequence. The concept of "sequence distance" quantifies this relationship through various metrics, including sequence identity, similarity scores, and evolutionary distances. Shorter sequence distances typically indicate closer functional relationships, but the mapping is not always linear—critical functional residues can be conserved even when overall sequence similarity is low. This nuanced relationship necessitates sophisticated algorithms that can detect subtle patterns beyond simple sequence alignment.

Computational Representations of Sequence Space

The transformation of biological sequences into computational representations enables the quantification and analysis of sequence distances. Early methods relied on direct sequence alignment algorithms like BLAST and hidden Markov models. Contemporary approaches employ learned representations from protein language models that capture higher-order dependencies and functional constraints. These models, such as Prot-T5 and ProtTrans, train on millions of protein sequences to learn embeddings that position functionally similar proteins closer in the representation space, even with low sequence similarity [31] [32]. The resulting multidimensional sequence space allows researchers to compute distances using mathematical metrics such as Euclidean distance, cosine similarity, or specialized biological distance metrics, creating a quantitative foundation for predicting drug-target relationships.

Methodological Approaches: Quantifying Sequence Distances

Sequence Similarity Metrics and Algorithms

Multiple computational approaches exist for quantifying relationships in sequence space, each with distinct advantages for drug repurposing applications:

Global Alignment Methods: Needleman-Wunsch and related algorithms provide overall similarity scores based on full-length sequence alignments, useful for identifying closely related targets with similar binding sites.

Local Alignment Methods: Smith-Waterman and BLAST identify conserved domains or motifs that may indicate functional similarity even in otherwise divergent proteins, particularly valuable for identifying cross-family relationships.

Profile-Based Methods: Position-Specific Scoring Matrices (PSSMs) and hidden Markov models capture evolutionary information from multiple sequence alignments, sensitive to distant homologies that might be missed by pairwise methods.

Embedding-Based Distances: Learned representations from protein language models enable distance calculations in a continuous space where proximity may indicate functional similarity beyond what is apparent from direct sequence comparison [31].

Feature Extraction from Protein Sequences

Beyond direct sequence comparison, researchers can extract physicochemical features that influence drug binding. The following table summarizes key feature categories used in sequence-based drug-target prediction:

Table 1: Feature Extraction Methods for Protein Sequences

| Feature Category | Specific Features | Biological Significance | Calculation Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Amino Acid Composition | 20 standard amino acid percentages | Influences structural stability and surface properties | Simple residue counting and normalization |

| Physicochemical Properties | Hydrophobicity, polarity, polarizability, charge, solvent accessibility, normalized van der Waals volume [33] | Determines binding pocket characteristics and interaction potentials | Various scales (e.g., Kyte-Doolittle for hydrophobicity) |

| Evolutionary Information | Position-Specific Scoring Matrix (PSSM), co-evolution patterns | Reveals functionally constrained residues | Multiple sequence alignment against reference databases |

| Language Model Embeddings | Context-aware residue representations from Prot-T5, ProtTrans [31] [32] | Captures complex sequence-function relationships | Forward pass through pre-trained transformer models |

Integration with Drug Representation

Effective drug-target relationship prediction requires complementary representation of compound structures. Simplified Molecular Input Line Entry System (SMILES) strings and molecular graphs are commonly used, with graph neural networks (GNNs) effectively extracting structural features [30] [33]. For drug repurposing applications, existing drugs can be represented by their chemical fingerprints, structural descriptors, or learned embeddings from compound language models. The integration of drug and target representations enables the prediction of interactions through various computational frameworks discussed in the following section.

Experimental Framework and Protocols

Core Workflow for Sequence Distance-Based Drug Repurposing

The following Graphviz diagram illustrates the comprehensive workflow for identifying drug repurposing candidates using sequence distance approaches:

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Building a Sequence Distance Matrix

Objective: Create a comprehensive distance matrix for all proteins in the target space.

Materials: Protein sequence database (SwissProt, RefSeq), multiple sequence alignment tool (ClustalOmega, MAFFT), feature extraction tools (ProDy, BioPython), distance calculation software.

Procedure:

- Data Collection: Retrieve sequences for all proteins of interest from reference databases.

- Multiple Sequence Alignment: Perform alignment using default parameters appropriate for the protein family.

- Feature Extraction: Generate feature vectors using selected methods from Table 1.

- Distance Calculation: Compute pairwise distances using appropriate metrics (Euclidean, cosine, Jaccard).