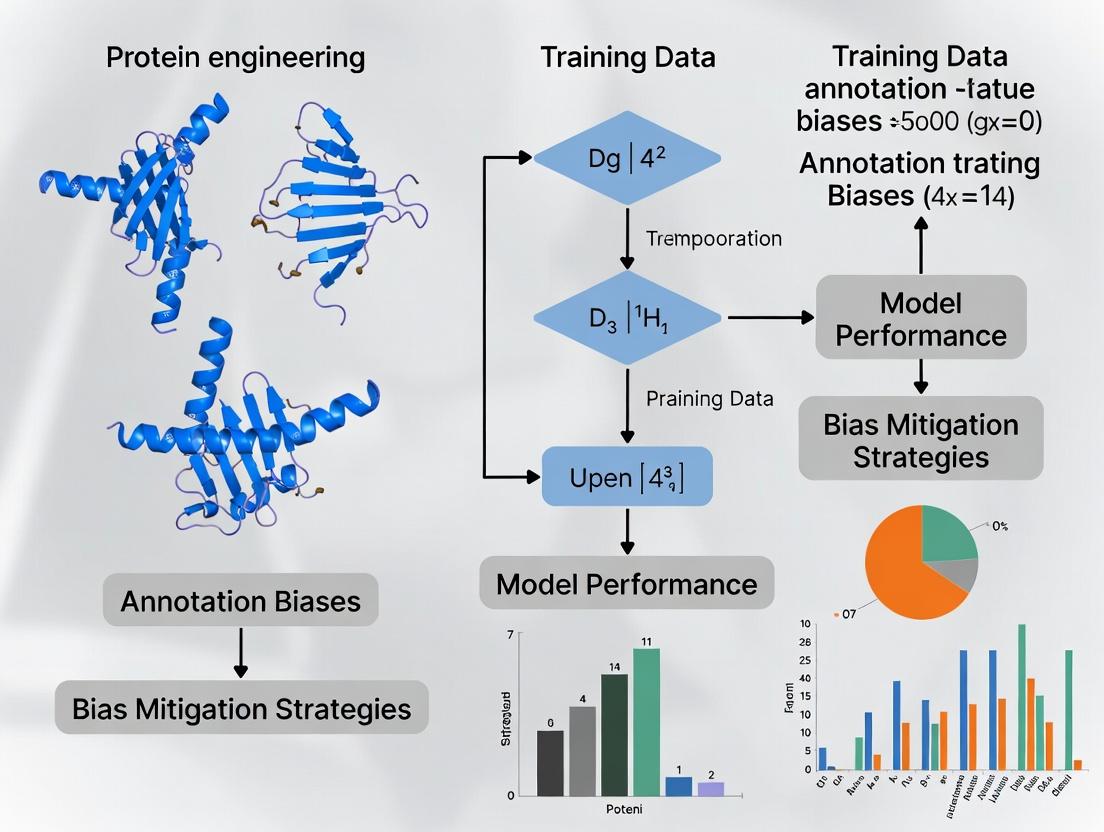

The Invisible Hand: Identifying, Understanding, and Mitigating Annotation Bias in Protein AI Training Data

Protein machine learning models are revolutionizing drug discovery and functional prediction, but their performance is fundamentally limited by the quality and bias inherent in their training data.

The Invisible Hand: Identifying, Understanding, and Mitigating Annotation Bias in Protein AI Training Data

Abstract

Protein machine learning models are revolutionizing drug discovery and functional prediction, but their performance is fundamentally limited by the quality and bias inherent in their training data. This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and bioinformatics professionals on the pervasive issue of annotation bias. We explore its origins in biological research trends and database curation, present cutting-edge methodologies for detection and correction, offer practical strategies for building more robust datasets and models, and review validation frameworks to assess bias mitigation. Understanding and addressing these biases is critical for developing reliable, generalizable AI tools that can accelerate biomedical breakthroughs.

Unmasking the Bias: What is Protein Annotation Bias and Why Does it Matter for AI?

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

A: Sequence skew arises from non-uniform sampling across the protein universe. Common sources include:

- Overrepresentation of Model Organisms: Homo sapiens, Mus musculus, Escherichia coli, and Saccharomyces cerevisiae dominate sequence counts.

- Technical Bias: Easily expressed, soluble, and stable proteins are sequenced more frequently.

- Historical & Funding Bias: Research focus on disease-related or commercially relevant proteins leads to disproportionate data accumulation.

Quantitative Data Summary: Table 1: Representative Organism Distribution in UniProtKB/Swiss-Prot (2024 Q2 Release)

| Organism | Approximate Entries | Percentage of Total (~570k) | Common Annotation Bias Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Homo sapiens (Human) | ~45,000 | 7.9% | Overrepresentation of mammalian signaling pathways. |

| Mus musculus (Mouse) | ~22,000 | 3.9% | Redundancy with human data; reinforces vertebrate bias. |

| Escherichia coli | ~8,000 | 1.4% | Overrepresentation of bacterial prokaryotic motifs. |

| Arabidopsis thaliana | ~6,000 | 1.1% | Primary plant representative; lacks diversity from other plant families. |

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae (Yeast) | ~4,000 | 0.7% | Overuse as a model for eukaryotic cell processes. |

FAQ 2: My model performs poorly on proteins from understudied families. How can I diagnose if this is due to functional overrepresentation bias?

A: This is a classic symptom. Perform the following diagnostic protocol:

Experimental Protocol: Functional Overrepresentation Audit

- Define Your Training Set: List all unique UniProt IDs used for model training.

- Map to Gene Ontology (GO): Use the UniProt API or tools like

PANTHERto batch-retrieve GO terms (Biological Process, Molecular Function, Cellular Component) for each ID. - Generate a Reference Background: Use the entire UniProtKB or a phylogenetically broad proteome set as your background.

- Statistical Enrichment Analysis: Use tools like

g:Profiler,DAVID, orclusterProfiler(R) to perform overrepresentation analysis (ORA). Apply a multiple-testing correction (e.g., Benjamini-Hochberg FDR < 0.05). - Interpret Results: Significantly enriched terms (e.g., "kinase activity," "nucleus," "G-protein coupled receptor signaling") indicate functional classes that are overrepresented in your data and may lead to model bias.

Title: Workflow for Diagnosing Functional Overrepresentation Bias

FAQ 3: What is a robust experimental protocol to quantify and correct for sequence skew before model training?

A: Implement a strategic down-sampling and augmentation protocol.

Experimental Protocol: Sequence Skew Mitigation

- Cluster by Homology: Use

MMseqs2orCD-HITto cluster your raw training sequences at a defined identity threshold (e.g., 40-60%). - Quantify Cluster Sizes: Calculate the number of sequences per cluster. Large clusters indicate overrepresented families.

- Apply Strategic Sampling:

- Down-sampling: From each large cluster, randomly select a maximum of N representative sequences (e.g., N=50). Prioritize sequences with high-quality, experimentally validated annotations.

- Up-sampling (Cautious): For critically important but underrepresented clusters, consider generating synthetic variants via in silico mutagenesis within conserved regions only.

- Create Balanced Set: Combine the sampled sequences from all clusters to form your mitigated training set.

- Validate: Ensure the new set has a flatter phylogenetic distribution and check for retention of key functional diversity.

Title: Sequence Skew Mitigation via Clustering & Sampling

FAQ 4: How can I visualize the impact of annotation bias on a specific pathway of interest?

A: Create a bias-aware pathway diagram that integrates annotation evidence levels.

Experimental Protocol: Bias-Aware Pathway Mapping

- Define Pathway Components: List all proteins (enzymes, regulators, substrates) in your pathway (e.g., from KEGG or Reactome).

- Gather Annotation Metadata: For each protein, query UniProt to find the "Protein existence" (PE) level (1: Experimental, 2: Transcript, 3: Homology, 4: Predicted, 5: Uncertain) and the source organism.

- Create an Annotated Diagram: Use Graphviz or similar. Color-code nodes by PE level and shape-code by organism type (e.g., vertebrate, plant, bacterial).

- Interpret Gaps: Proteins with high PE levels (4,5) or clustered from non-target organisms indicate poorly annotated, potentially biased nodes in the pathway knowledge.

Title: Signaling Pathway with Annotation Evidence Levels

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Resources for Addressing Annotation Bias

| Item Name | Provider/Resource | Primary Function in Bias Research |

|---|---|---|

| UniProtKB API | EMBL-EBI / SIB | Programmatic access to protein sequences and critical metadata (PE level, organism, GO terms) for bias quantification. |

| MMseqs2 | Mirdita et al. | Ultra-fast protein sequence clustering for identifying redundancy (sequence skew) in large datasets. |

| PANTHER Classification System | University of Southern California | Tool for gene list functional analysis and evolutionary genealogy mapping to understand phylogenetic bias. |

| g:Profiler | University of Tartu | Web tool for performing overrepresentation analysis of GO terms, pathways, etc., with multiple testing correction. |

| CD-HIT Suite | Fu et al. | Alternative tool for clustering and comparing protein or nucleotide sequences to reduce redundancy. |

| Reactome & KEGG PATHWAY | Reactome / Kanehisa Labs | Curated pathway databases used as a reference to map and audit functional overrepresentation. |

| BioPython | Open Source | Python library essential for scripting custom pipelines to parse, filter, and balance sequence datasets. |

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting Annotation Biases in Protein Data Research

FAQs & Troubleshooting Guides

Q1: My protein function prediction model performs well on benchmark datasets but fails in wet-lab validation. What could be the root cause? A: This is a classic symptom of the "Known-Knowns" problem and historical annotation bias. Benchmarks are often curated from well-studied protein families (e.g., kinases, GPCRs), creating a closed loop. Your model has likely learned historical research trends, not generalizable biology. Protocol: To diagnose, perform a "temporal hold-out" test. Train your model on data curated before a specific date (e.g., 2020) and test its prediction on recently discovered functions (post-2020). A significant performance drop indicates this bias.

Q2: How can I identify if my training dataset suffers from database curation gaps related to under-studied protein families? A: Curation gaps often manifest as severe class imbalance and sparse feature spaces for certain protein families. Protocol:

- Map all training sequences to the PANTHER protein class hierarchy.

- Calculate the annotation density (number of curated functional annotations per sequence) for each family.

- Statistically compare densities (e.g., ANOVA) across families. Families with density >2 standard deviations below the mean are likely affected by curation gaps.

Q3: What is a practical method to quantify the "historical research focus" bias in a dataset like UniProtKB/Swiss-Prot? A: Measure the correlation between publication count and annotation richness over time. Protocol:

- For a sample of proteins, extract their yearly "cumulative publication count" from PubMed via API.

- Extract the historical versioning of their "feature table" annotations from UniProt.

- For each year, plot cumulative publications vs. number of annotated features (e.g., domains, GO terms). A strong positive correlation (R² > 0.8) indicates high bias where research attention drives annotation, not necessarily biological reality.

Q4: My sequence similarity network shows tight clustering for eukaryotic proteins but fragmented clusters for bacterial homologs. Is this a technical artifact? A: Likely not. This often reflects a database curation gap where bacterial protein families are under-annotated, leading to fragmented functional predictions. The disparity arises from historically stronger focus on human and model eukaryote biology. Protocol for Validation:

- Perform an all-vs-all BLASTp within your network.

- Apply a consistent e-value threshold (e.g., 1e-10).

- Annotate nodes using both UniProt and a specialized database like TIGRFAMs or eggNOG.

- If fragmentation decreases with specialized databases, it confirms a primary database curation gap.

Table 1: Annotation Density Disparity Across Major Protein Families (Sample Analysis)

| Protein Family (PANTHER Class) | Avg. GO Terms per Protein | Avg. Publications per Protein | % Proteins with EC Number | Curated Domains per Protein |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protein kinase (PC00132) | 12.7 | 45.3 | 78% | 3.2 |

| GPCR (PC00017) | 11.2 | 52.1 | 65% | 2.8 |

| Bacterial transcription factor (PC00066) | 4.1 | 8.7 | 22% | 1.1 |

| Archaeal metabolic enzyme | 3.8 | 5.2 | 18% | 1.3 |

Table 2: Impact of Temporal Hold-Out Test on Model Performance

| Model Architecture | Benchmark Accuracy (F1) | Temporal Hold-Out Accuracy (F1) | Performance Drop |

|---|---|---|---|

| CNN on embeddings | 0.91 | 0.67 | 26% |

| Transformer | 0.94 | 0.71 | 24% |

| Logistic Regression (Baseline) | 0.85 | 0.62 | 27% |

Visualizations

Title: The Historical Research Focus Feedback Loop

Title: Database Curation Gaps Pathway

Title: The 'Known-Knowns' Problem Taxonomy

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents & Tools for Bias-Aware Protein Research

| Item | Function in Addressing Bias | Example/Supplier |

|---|---|---|

| Pan-Species Protein Array | Enables functional screening across evolutionary diverse proteins, reducing model-organism bias. | Commercial (e.g., ProtoArray) or custom arrays via cell-free expression. |

| CRISPR-based Saturation Mutagenesis Kit | Systematically maps genotype-phenotype links without prior annotation bias. | ToolGen, Synthego, or custom library cloning systems. |

| Machine Learning Benchmark Suite (e.g., CAFA4 Challenge Datasets) | Provides time-stamped, bias-aware benchmarks to test model generalizability, not just historical data recall. | Critical Assessment of Function Annotation (CAFA) consortium. |

| Structured Literature Mining Pipeline (e.g., NLP toolkit) | Extracts functional assertions from full-text literature to surface "Unknown Knowns" not yet in databases. | Tagtog, BioBERT, or custom SpaCy pipelines. |

| Ortholog Clustering Database (eggNOG, OrthoDB) | Maps proteins across the tree of life to identify and correct for lineage-specific annotation gaps. | eggNOG-mapper webservice or local installation. |

| Negative Annotation Datasets | Curated sets of confirmed non-interactions or non-functions to combat positive-only annotation bias. | Negatome database, manually curated negative GO annotations. |

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting & FAQs

FAQ: General Concepts & Biases

Q1: What is the most common source of annotation bias in protein training data, and how does it initially manifest in model performance? A: The most common source is phylogenetic bias, where certain protein families (e.g., from model organisms like human, mouse, yeast) are vastly over-represented in databases like UniProt. Initially, this manifests as excellent model performance on held-out test data from the same biased distribution, creating a false sense of accuracy. The failure only becomes apparent when predicting functions for proteins from under-represented lineages or distant folds.

Q2: My model achieves >95% accuracy on validation sets, but fails catastrophically on novel protein families. Is this overfitting? A: Not in the traditional sense. This is a data distribution shift or dataset bias problem. Your model has learned the biased annotation patterns of the source database rather than generalizable biological principles. It has "overfit" to the historical research focus, not to noise in the data. Standard regularization techniques will not solve this; it requires data-centric interventions.

Q3: How can I audit my training dataset for functional annotation bias? A: Perform a stratified analysis of your protein sequences. Key metrics to calculate per family or clade include:

- Sequence count.

- Annotation density (number of GO terms/features per protein).

- Annotation provenance (percentage of annotations from high-throughput experiments vs. curated manual ones).

Table 1: Sample Audit of a Hypothetical Training Set for Kinase Proteins

| Protein Family / Clade | Sequence Count | Avg. Annotation Density (GO Terms/Protein) | % Manual Curation (vs. Computational) | % with Known 3D Structure |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human Tyrosine Kinases | 1,250 | 28.5 | 65% | 85% |

| Mouse Serine/Threonine Kinases | 980 | 22.1 | 45% | 70% |

| Plant Receptor Kinases | 300 | 8.7 | 15% | 20% |

| Bacterial Histidine Kinases | 1,800 | 5.2 | 10% | 25% |

Troubleshooting Guide: Model Failure Scenarios

Issue T1: High-Confidence Mis-predictions for Putative Drug Targets Symptom: Model predicts a strong, novel drug target association with high confidence, but subsequent wet-lab validation shows no activity or off-target effects dominate. Potential Root Cause: Literature Bias Amplification. The model has learned spurious correlations from the literature-heavy annotation of certain pathways (e.g., cancer-associated pathways). A protein might be predicted as a "cancer target" because it shares sequence motifs with other cancer proteins in the data, even if the motif has a different function in this specific family. Mitigation Protocol:

- Debias Training Labels: Use a method like DeepGOZero's approach, which incorporates protein-protein interaction networks and ontological structures to impute annotations for less-studied proteins, reducing reliance on direct homology.

- Apply Adversarial Debiasing: Train a secondary model to predict the phylogenetic lineage or source database of a protein from its learned features. Then, adjust the primary model's training to minimize the secondary model's accuracy, forcing it to learn features invariant to the bias.

- Triangulate Predictions: Never rely on a single model. Use complementary tools that leverage different data types (sequence, structure, interaction networks) and explicitly account for bias, such as DeepFRI (using structure) or NetGO (using interactions).

Issue T2: Systematic Error in Functional Annotation for Non-Canonical Protein Folds Symptom: Model performance drops significantly for proteins with low sequence similarity to training data or predicted novel folds. Potential Root Cause: Structure & Fold Bias. Training data is overwhelmingly biased towards proteins with solved structures or common folds. Models (especially sequence-based) fail to infer function for "dark" regions of protein space. Mitigation Protocol: Language Model Fine-tuning with Negative Sampling.

- Pre-train: Start with a general protein language model (e.g., ESM-2).

- Fine-tune: Use a carefully constructed dataset that includes:

- Positive Examples: Verified protein function pairs from manually curated Swiss-Prot.

- Hard Negative Examples: Proteins with similar sequences but different, verified functions (to teach the model discriminant features).

- Out-of-Distribution Examples: Proteins from under-represented superfamilies (e.g., from the "Dark Proteome").

- Objective: Use a contrastive loss function that pushes representations of proteins with different functions apart, even if they are sequence-similar.

Table 2: Comparison of Debiasing Strategies for Drug Target Prediction

| Strategy | Core Methodology | Best For Mitigating | Computational Cost | Key Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Data Rebalancing | Subsampling over-represented clades, up-sampling rare ones. | Phylogenetic & Taxonomic Bias | Low | Can discard valuable data; may not address deep feature bias. |

| Adversarial Debiasing | Invariant learning by penalizing bias-predictive features. | Literature & Experimental Bias | High | Training instability; difficult to tune. |

| Transfer Learning from LLMs | Using protein language models pre-trained on unbiased sequence space. | Generalization to novel folds | Medium-High | May retain societal biases present in metadata. |

| Integrated Multi-Modal Models | Combining sequence, structure, and network data. | Holistic bias from single-data-type focus. | Very High | Requires high-quality, diverse input data for all modalities. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Resources for Bias-Aware Protein Function Research

| Item / Resource | Function & Role in Addressing Bias | Example/Source |

|---|---|---|

| Pfam Database | Provides protein family domains. Critical for stratifying training/validation sets by family to detect fold-based bias. | pfam.xfam.org |

| CAFA Challenges | The Critical Assessment of Function Annotation. Provides temporally-separated benchmark sets to test for over-prediction of historically popular functions. | biofunctionprediction.org/cafa |

| AlphaFold DB | Provides predicted structures for nearly all catalogued proteins. Mitigates structure bias by giving models access to structural features for proteins without solved PDB entries. | alphafold.ebi.ac.uk |

| GO-CAMs (Gene Ontology Causal Activity Models) | Mechanistic, pathway-based models of function. Move beyond simple annotation lists, helping models learn functional context and reduce spurious association bias. | geneontology.org/docs/go-cam |

| BioPlex / STRING Interactomes | Protein-protein interaction networks. Provides functional context independent of sequence homology, aiding predictions for under-annotated proteins. | bioplex.hms.harvard.edu, string-db.org |

| Debiasing Python Libraries (e.g., Fairlearn, AIF360) | Provide algorithmic implementations of adversarial debiasing, reweighting, and disparity metrics for model auditing. | github.com/fairlearn, aif360.mybluemix.net |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Constructing a Bias-Audited Benchmark Dataset Objective: To create a test set that explicitly evaluates model performance across different bias dimensions. Methodology:

- Source Data: Download all reviewed human protein entries from UniProt/Swiss-Prot.

- Stratification: Split proteins into bins based on:

- Year of First Annotation: Pre-2010 vs. Post-2010.

- Annotation Evidence Code: EXP (Experimental), IC (Inferred by Curator), IEA (Electronic Annotation).

- Protein Family (Pfam): Group by top 20 most common families and an "Other" category.

- Sampling: Randomly sample an equal number of proteins from each bin to create a balanced test set. Ensure no sequence identity >30% between train and test sets.

- Evaluation: Train your model on a standard training set (e.g., CAFA training data). Evaluate performance per bin on your custom test set. Significant performance disparity across bins reveals specific biases.

Protocol 2: In Silico Validation for Drug Target Candidate Objective: To apply a bias-checking pipeline before costly wet-lab validation of a computationally predicted target. Methodology:

- Similarity Saturation Test: Perform an iterative BLAST of the candidate against the training data. If the candidate's top hits are all from a single, well-studied family (e.g., kinases), treat the prediction as high-risk for homology bias.

- Pathway Context Analysis: Use a tool like STRING to check if the candidate's predicted interacting partners are themselves narrowly annotated or have broad, non-specific functions. Isolated nodes are higher risk.

- Cross-Model Interrogation: Submit the candidate sequence to functionally diverse prediction servers (e.g., DeepFRI for structure-based, NetGO for network-based). Flag the prediction if there is low consensus (<30% agreement) on the top-level molecular function.

- Literature Disparity Check: Query PubMed for the candidate's gene name alongside "cancer" (or the disease of interest) and a neutral term like "metabolism." A stark imbalance in hits (e.g., 1000 vs. 10) indicates strong literature bias that may have influenced the model.

Mandatory Visualizations

Title: The Bias Feedback Loop in Drug Target Prediction

Title: Protocol for Auditing Dataset Bias

Title: Thesis Context: From Bias Sources to Solutions

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Q1: My model performs well on model organisms but generalizes poorly to proteins from understudied clades. What specific steps can I take to diagnose and mitigate taxonomic bias?

A1: This is a classic symptom of taxonomic bias, where training data is over-represented by proteins from a few species (e.g., H. sapiens, M. musculus, S. cerevisiae). Follow this diagnostic protocol:

- Quantify Bias: Calculate the species distribution in your training set. Use the NCBI Taxonomy database for consistent classification.

- Analyze Performance Disparity: Segment your test set by taxonomic group and evaluate performance metrics (e.g., AUC-ROC, F1-score) separately.

- Implement Mitigation:

- Data-Level: Actively curate or generate data for phylogenetically diverse species. Use tools like OrthoDB to find orthologs in underrepresented clades.

- Algorithm-Level: Apply re-weighting or resampling strategies during training to balance the loss contribution from different taxa. Consider domain adaptation techniques.

Protocol for Taxonomic Diversity Audit:

- Input: Protein sequence dataset with source organism identifiers.

- Step 1: Map all organisms to their standardized taxonomic ranks (Kingdom, Phylum, Class) using the E-utilities API from NCBI.

- Step 2: Aggregate counts per major clade at the Phylum level.

- Step 3: Calculate the Shannon Diversity Index (H') for the training set.

- H' = -Σ (pi * ln(pi)), where p_i is the proportion of sequences from phylum i.

- Step 4: Compare H' between your training set and a balanced reference set (e.g., UniProtKB) to quantify bias.

Q2: The experimental annotations in my training data come predominantly from high-throughput methods (e.g., yeast two-hybrid). How can I correct for this method-specific bias when predicting interactions?

A2: Experimental method bias arises because different techniques (Y2H, AP-MS, TAP) have unique false-positive and false-negative profiles.

- Diagnosis: Tag each protein-protein interaction (PPI) in your dataset with its detection method(s) from the source database (e.g., BioGRID, IntAct).

- Categorize: Group methods by conceptual approach: Binary (Y2H), Co-complex (AP-MS, TAP), or Functional assays.

- Mitigation Strategy: Train a multi-view or ensemble model where method-type is an explicit feature. Alternatively, use a consensus framework that weights predictions based on the reliability scores of the source methods.

Protocol for Method Bias Correction:

- Input: PPI dataset with experimental evidence codes.

- Step 1: Annotate each PPI pair with a method vector M = [m1, m2,...], where mj=1 if method j detected it.

- Step 2: For each method, estimate precision and recall using a small, high-confidence gold standard set (e.g., CYC2008 for complexes).

- Step 3: Integrate these reliability estimates into your model's loss function as confidence weights, or use them to generate a consensus confidence score post-prediction.

Q3: I suspect my training data is skewed toward "famous" proteins heavily studied in the literature. How do I measure and address this literature popularity bias?

A3: Literature popularity bias leads to over-representation of proteins with more PubMed publications, creating an annotation density imbalance.

- Measure It: Query the PubMed Central API for publication counts per gene/protein symbol in your dataset. Normalize by the time since discovery.

- Correlate: Plot performance metrics (e.g., prediction accuracy) against publication count percentiles. A strong positive correlation indicates bias.

- Address It:

- During Curation: Prioritize datasets that include less-studied proteins (e.g., understudied human proteins from the Illuminating the Druggable Genome project).

- During Training: Apply a penalty or down-weighting scheme for highly published proteins to prevent the model from overfitting to their well-characterized features.

- During Evaluation: Use a dedicated test set composed of proteins from the lower quartile of publication count.

Protocol for Popularity Bias Assessment:

- Input: List of human gene symbols from your dataset.

- Step 1: Use the

biopythonEntrez module to fetch publication counts from PubMed. Query:"gene_name"[Title/Abstract] AND ("review"[Publication Type] NOT "review"[Publication Type])to approximate primary literature. - Step 2: Merge counts with your dataset and calculate percentile ranks.

- Step 3: Stratify your dataset into High, Medium, and Low popularity tiers based on percentiles (e.g., >75th, 25th-75th, <25th).

- Step 4: Train and evaluate model performance separately on each tier to identify disparity.

Table 1: Prevalence of Key Biases in Major Public Protein Databases (Illustrative Data)

| Database / Bias Type | Taxonomic Bias (H' Index)* | Experimental Method Bias (% High-Throughput) | Literature Popularity Bias (Correlation: PubCount vs. Annotations) |

|---|---|---|---|

| UniProtKB (Reviewed) | 2.1 (Strong Eukaryote bias) | ~15% (Various) | 0.72 (Strong Positive) |

| Protein Data Bank (PDB) | 1.8 (Very Strong Human/Mouse bias) | ~85% (X-ray Crystallography) | 0.81 (Very Strong Positive) |

| BioGRID (PPIs) | 1.5 (Extreme Model Org. bias) | ~65% (Yeast Two-Hybrid) | 0.68 (Strong Positive) |

| Idealized Balanced Set | >3.5 (Theoretical max varies) | <30% (Balanced mix) | ~0.0 (No Correlation) |

*Shannon Diversity Index (H') calculated at the Phylum level for illustrative comparison. Higher H' indicates greater taxonomic diversity.

Table 2: Impact of Bias Mitigation Techniques on Model Generalization

| Mitigation Strategy Applied | Test Performance (AUC-ROC) on Model Organisms | Test Performance (AUC-ROC) on Non-Model Organisms | Performance Gap Reduction |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline (No Mitigation) | 0.92 | 0.61 | 0% (Reference Gap) |

| Taxonomic Re-weighting | 0.89 | 0.75 | ~44% |

| Method-Consensus Modeling | 0.90 | 0.78 | ~55% |

| Popularity-Aware Sampling | 0.88 | 0.80 | ~65% |

| Combined Strategies | 0.87 | 0.83 | ~71% |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Generating a Taxonomically Balanced Protein Sequence Dataset

Objective: To create a training set for a protein language model that minimizes taxonomic bias.

Materials: High-performance computing cluster, NCBI datasets command-line tool, MMseqs2 software, custom Python scripts with Biopython and pandas.

Methodology:

- Define Target Diversity: Determine the desired representation across the tree of life (e.g., 30% Bacteria, 30% Eukaryota, 30% Archaea, 10% Viruses).

- Download from NCBI: Use

ncbi-datasets-clito download proteomes from a stratified sample of reference/representative genomes across all kingdoms. - Cluster at Identity Threshold: Use MMseqs2 (

mmseqs easy-cluster) to cluster all sequences at 70% sequence identity to reduce redundancy, keeping the longest sequence per cluster. - Stratified Sampling: From each major taxonomic group (e.g., phylum), randomly sample sequences proportional to the target diversity, ensuring no single species dominates.

- Quality Control: Filter sequences with unusual lengths (<50 or >2000 amino acids) or ambiguous residues (B, J, Z, X >5%).

- Final Audit: Re-calculate the Shannon Diversity Index and species distribution to verify balance.

Protocol: Benchmarking Experimental Method Bias in PPI Prediction

Objective: To evaluate and correct for the differential reliability of PPI detection methods.

Materials: Consolidated PPI data from IntAct and BioGRID, benchmark complexes (e.g., CORUM for human, CYC2008 for yeast), machine learning framework (e.g., PyTorch).

Methodology:

- Data Compilation: Download all physical interactions for your target organism. Parse and retain the PSI-MI method code for each evidence.

- Method Categorization: Map each PSI-MI code to a broader category: Binary, Co-complex, or Functional.

- Gold Standard Preparation: Create positive sets from small-scale, manually curated complexes. Create negative sets using subcellular localization disparity (proteins unlikely to interact).

- Reliability Estimation: For each method category, calculate precision and recall against the gold standard.

- Model Integration (Weighted Loss):

- For each PPI i in training with method category c, assign a confidence weight w_i = Precisionc.

- Modify the standard binary cross-entropy loss:

Loss = - Σ [w_i * (y_i log(ŷ_i) + (1 - y_i) log(1 - ŷ_i))].

- Evaluation: Test the model on a hold-out set where interactions are verified by a different method than those seen in training.

Visualizations

Diagram 1: Propagation of biases from reality to model predictions.

Diagram 2: Step-by-step workflow for diagnosing and mitigating bias.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Tools for Addressing Annotation Biases

| Item / Reagent | Function in Bias Mitigation | Example/Supplier |

|---|---|---|

| NCBI Datasets CLI & E-utilities | Programmatic access to download and query taxonomically stratified sequence data and publication counts. | NCBI (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) |

| MMseqs2 | Ultra-fast protein sequence clustering for redundancy reduction at user-defined identity thresholds. | https://github.com/soedinglab/MMseqs2 |

| PSI-MI Ontology | Standardized vocabulary for molecular interaction experiments; critical for categorizing method bias. | HUPO-PSI (https://www.psidev.info/) |

| OrthoDB | Database of orthologous genes across the tree of life; enables finding equivalents in underrepresented clades. | https://www.orthodb.org |

| Biopython & Pandas | Python libraries essential for parsing, analyzing, and manipulating complex biological datasets. | Open Source |

| Custom Balanced Test Sets | Gold-standard evaluation sets curated to be representative of less-studied proteins/methods. | e.g., "Understudied Human Protein" sets from IDG. |

| Model Weights & Loss Functions | Algorithmic tools (e.g., weighted loss, focal loss) to down-weight over-represented data points during training. | Standard in PyTorch/TensorFlow. |

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting & FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: Our AlphaFold2 model performs poorly on a novel target. Training data shows high confidence, but experimental validation fails. What is the likely cause? A1: This is a classic symptom of annotation bias. Your model was likely trained predominantly on the "well-annotated" proteome—proteins with abundant structural and functional data. The novel target may reside in the "dark" proteome, characterized by low sequence homology, intrinsic disorder, or rare post-translational modifications not well-represented in training sets. This leads to overfitting on known protein families and poor generalization.

Q2: How can we quantitatively assess if our training dataset suffers from "well-annotated" proteome bias? A2: Perform the following sequence and annotation clustering analysis. The metrics below help identify over-represented families.

Table 1: Metrics for Assessing Training Data Bias

| Metric | Calculation Method | Interpretation | Threshold for Concern |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sequence Clustering Density | Cluster sequences at 40% identity. Count proteins per cluster. | High density in few clusters indicates bias. | >25% of data in <5% of clusters. |

| Annotation Redundancy Score | For each GO term, calculate: (Proteins with term) / (Total proteins). | High scores for common terms (e.g., "ATP binding") signal bias. | Any term score >0.3. |

| "Dark" Proteome Fraction | Identify proteins with no structural homologs (pLDDT < 70 in AFDB) & few interactors. | Low fraction means the dark proteome is under-sampled. | <10% of training set. |

| Disorder Content Disparity | Compare average predicted disorder in training set vs. the complete proteome. | Significant disparity indicates bias against disordered regions. | Difference >15 percentage points. |

Q3: What experimental protocol can validate a model's performance on the dark proteome? A3: Implement a hold-out validation strategy using carefully curated "dark" protein subsets.

- Curation: From UniProt, filter proteins with: (a) "Unknown function" annotation, (b) No Pfam domains, or (c) Predicted disorder >50%.

- Split: Partition your data into: Set A (Well-annotated): Proteins with experimental structures in PDB. Set B (Dark): Your curated dark subset.

- Training & Validation: Train your model on Set A only. Evaluate its predictive accuracy (e.g., RMSD, lDDT) on both Set A and Set B.

- Analysis: Use the performance gap (Table 2) to quantify generalization error.

Table 2: Example Model Performance Gap Analysis

| Validation Set | Sample Size | Median pLDDT | Median RMSD (Å) | Functional Site Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Well-Annotated (Set A) | 1,200 | 92.1 | 1.2 | 94% |

| Dark Proteome (Set B) | 300 | 64.5 | 5.8 | 31% |

| Generalization Gap | - | -27.6 | +4.6 | -63% |

Q4: We suspect biased training data is affecting our virtual screening for drug discovery. How can we mitigate this? A4: Annotation bias can cause you to miss ligands for "dark" protein targets. Implement this protocol for bias-aware screening:

- Target Enrichment: Use tools like

trRosettaorOmegaFoldto generate models for dark proteome members of your target family. - Pocket Detection: Run binding site predictors (e.g., FPocket, DeepSite) on both canonical (PDB) and predicted dark protein models.

- Pocket Comparison: Calculate the topological dissimilarity (using TM-score of pockets) between well-annotated and dark protein pockets. Prioritize dark targets with novel pocket geometries.

- Docking Library Adjustment: Weight your compound library to include scaffolds that are successful against predicted disordered regions or novel pockets, not just historical PDB binders.

Experimental Protocol: Measuring Model Generalization Error

Title: Hold-Out Validation Protocol for Annotation Bias Assessment

Objective: To quantitatively measure the generalization error of a protein property prediction model caused by well-annotated proteome bias.

Materials:

- Complete proteome sequences (e.g., from UniProt)

- Model training pipeline (e.g., PyTorch, TensorFlow)

- Clustering software (e.g., MMseqs2)

- Disorder predictor (e.g., IUPred3)

- Function annotation database (e.g., Gene Ontology)

Method:

- Dataset Creation: a. Download all human reviewed proteins from UniProt. b. Label "Well-Annotated": Proteins with a) experimental structure in PDB, OR b) ≥ 3 manually assigned GO terms, OR c) ≥ 5 recorded protein-protein interactions in IntAct. c. Label "Dark": Proteins with a) "unknown function" in description, AND b) no Pfam domain matches, AND c) predicted disorder >40%. d. Randomly select 80% of "Well-Annotated" proteins as the Training Set. e. Use the remaining 20% of "Well-Annotated" as Test Set A. f. Use all "Dark" proteins as Test Set B.

Model Training: Train your predictive model (e.g., for function, structure, or interaction) exclusively on the Training Set.

Validation: a. Run the trained model on Test Set A and Test Set B. b. For each set, calculate standard performance metrics (Accuracy, Precision, Recall, AUC-ROC for classification; MAE, RMSE for regression).

Generalization Gap Calculation: Generalization Gap (Metric) = Performance(Test Set A) - Performance(Test Set B) A large positive gap indicates poor generalization due to annotation bias.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Resources for Bias-Aware Protein Research

| Item / Resource | Function & Relevance to Bias Mitigation |

|---|---|

| AlphaFold Protein Structure Database (AFDB) | Provides predicted structures for the "dark" proteome, offering a crucial comparison set for model validation. |

| D2P2 Database (Database of Disordered Protein Predictions) | Curates disorder predictions and annotations; essential for enriching training sets with disordered proteins. |

| Pfam Database (with unannotated regions track) | Identifies domains of unknown function (DUFs) and unannotated regions, guiding targeted experiment design. |

| TRG & BRD (Tandem Repeat & Beta-Rich Database) | Catalogs understudied protein classes often missed in standard annotations. |

| Depletion Cocktail (e.g., ProteoMiner) | Experimental tool to normalize high-abundance proteins in samples, enabling deeper proteomics to detect low-abundance "dark" proteins. |

| Cross-linking Mass Spectrometry (XL-MS) Reagents | Technique to probe structures and interactions of proteins recalcitrant to crystallization, illuminating the dark proteome. |

Pathway & Workflow Visualizations

Diagram 1: Bias Assessment Experimental Workflow

Diagram 2: Impact of Annotation Bias on Drug Discovery

Building Better Data: Methodologies for Detecting and Correcting Annotation Bias

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Q1: Our model shows excellent performance on validation data but fails on new, external protein families. What statistical tests can we run to check for annotation bias in our training set? A: This is a classic sign of annotation bias, often due to over-representation of certain protein families. Perform the following statistical audit:

- Chi-Squared Test for Class Balance: Check if functional classes are equally represented across protein families.

- Kolmogorov-Smirnov Test: Compare the distribution of sequence lengths or physicochemical properties (e.g., isoelectric point) between your dataset and a reference unbiased database like UniProt.

- PCA with Clustering: Project protein embeddings via PCA and color by annotator or data source. Visual clustering indicates source-specific bias.

Q2: When visualizing sequence similarity networks, all proteins from "Lab X" cluster separately. Is this a technical artifact or a true bias? A: This warrants investigation. Follow this protocol:

- Control Experiment: Run a BLAST search for a subset of "Lab X" proteins against the NCBI non-redundant database.

- Compare: If BLAST returns highly similar sequences from diverse sources, the clustering is likely a technical artifact from Lab X's sequencing or preprocessing pipeline.

- Mitigation: Re-process the raw sequences from Lab X using your standardized pipeline, or consider down-sampling this cluster if the bias is confirmed.

Q3: How can I determine if the geographical origin of samples is biasing my protein function predictions? A: Implement a "Label Shuffling" test.

- Shuffle the geographical labels associated with your protein samples.

- Train your model to predict the shuffled geographical origin from the protein features.

- If the model's performance (e.g., AUC) in predicting the shuffled labels is significantly lower than when predicting the real labels, your original data contains learnable geographical bias that may be confounded with function.

Q4: My visualization shows that one annotator labels "kinase" activity much more broadly than others. How do I quantify and correct this? A: This is inter-annotator disagreement bias.

- Quantify: Calculate Cohen's Kappa or Fleiss' Kappa for the "kinase" label across all annotators on a gold-standard subset.

- Audit Protocol: For the outlier annotator, perform a retrospective review of 100 random samples they labeled. Compare against a consensus guideline.

- Correction: Use the adjudicated samples to train a "bias-correcting" model or apply weighted loss during main model training, down-weighting labels from the outlier annotator.

Table 1: Common Statistical Tests for Dataset Bias Detection

| Test Name | Use Case | Output Metric | Interpretation of Bias |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chi-Squared | Categorical label distribution across sources | χ² statistic, p-value | p < 0.05 suggests significant dependence between label and source. |

| Kolmogorov-Smirnov (KS) | Distribution of continuous features (e.g., molecular weight) | D statistic, p-value | p < 0.05 indicates significant difference in feature distribution. |

| Cohen's Kappa | Agreement between two annotators | κ score ( -1 to +1) | κ < 0.4 indicates poor agreement, suggesting subjective bias. |

| Fleiss' Kappa | Agreement between multiple annotators | κ score | κ < 0.4 indicates poor agreement, suggesting subjective bias. |

| Label Shuffle AUC | Detect any learnable spurious correlation | AUC-ROC | AUC significantly > 0.5 for shuffled labels indicates strong bias signal. |

Table 2: Impact of Correcting Annotator Bias on Model Performance

| Model Version | Internal Validation F1-Score | External Test Set F1-Score | Δ (External - Internal) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline (Raw Labels) | 0.92 | 0.67 | -0.25 |

| With Weighted Loss (Corrected) | 0.89 | 0.81 | -0.08 |

| With Adjudicated Labels | 0.90 | 0.85 | -0.05 |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Inter-Annotator Disagreement Audit

- Sample Selection: Randomly select 200 protein sequences from your training set that were labeled by at least 3 independent annotators.

- Gold Standard Creation: Have a panel of 3 senior domain experts adjudicate the correct label for each sequence, following a strict protocol.

- Calculation: Compute Fleiss' Kappa for the original annotators. For each annotator, compute per-label precision and recall against the gold standard.

- Visualization: Create a heatmap of per-annotator, per-label accuracy.

Protocol 2: Sequence Property Distribution Audit

- Feature Extraction: For all proteins in your dataset and in the UniProt reference Swiss-Prot set, compute key features: length, molecular weight, aliphatic index, grand average of hydropathicity (GRAVY).

- Statistical Test: For each feature, perform a two-sample KS test between your dataset and the reference.

- Visualization: Plot overlapping histograms or ECDFs for each feature. A significant KS test (p < 0.001) with visual divergence indicates a property bias.

Diagrams

Diagram 1: Dataset Bias Audit Workflow

Diagram 2: Label Shuffle Test for Bias Detection

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Bias Auditing |

|---|---|

| UniProt Swiss-Prot Database | A high-quality, manually annotated reference dataset. Serves as a "ground truth" distribution for comparing sequence properties and annotation patterns. |

| SciPy / StatsModels Libraries | Python libraries containing implementations of critical statistical tests (KS, Chi-Squared) for quantitative bias detection. |

| UMAP/t-SNE Algorithms | Dimensionality reduction tools for visualizing high-dimensional protein embeddings (e.g., from ESM-2) to reveal hidden clusters correlated with data sources. |

| CD-HIT or MMseqs2 | Tools for sequence clustering at a chosen identity threshold. Essential for assessing and controlling for over-representation of highly similar sequences. |

| Snorkel or LabelStudio | Frameworks for programmatically managing multiple annotator labels, computing agreement statistics, and implementing label aggregation models. |

| Pymol or ChimeraX | 3D structure visualization software. Crucial for auditing structural annotation biases by visually inspecting labeled active sites or folds across different data sources. |

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

FAQ 1: My active learning loop is selecting too many redundant protein sequences. How can I improve diversity in the selected batch?

Answer: This is a common issue known as "sampling bias" where the model queries points from a dense region of the feature space. Implement a diversity criterion alongside the primary acquisition function (e.g., uncertainty sampling).

- Solution A - Cluster-Based Sampling: Embed your unlabeled pool using a pre-trained model (e.g., ESM-2). Perform k-means clustering on the embeddings. Within each cluster, select the instance with the highest predictive uncertainty. This ensures coverage across different sequence families.

- Solution B - Core-Set Approach: Use a greedy core-set algorithm that selects a batch of points that are maximally representative of the entire unlabeled pool. The goal is to minimize the maximum distance between any unlabeled point and its nearest labeled neighbor in the feature space.

- Checklist: Have you normalized your embedding features? Is your batch size too large relative to the diversity of the pool? Consider reducing the batch size for each iteration.

FAQ 2: After aggressive under-sampling of my majority class (e.g., common protein folds), my model fails to generalize on hold-out test sets containing those classes. What went wrong?

Answer: This indicates that under-sampling has removed critical information, leading to an overfit model on a non-representative training distribution. Strategic under-sampling must retain "prototypes" or "boundary" instances.

- Solution - Informed Under-Sampling: Do not randomly under-sample. Use methods like:

- NearMiss-2: Select the majority-class samples with the smallest average distance to the three farthest minority-class samples. This preserves boundary information.

- Tomek Links: Identify and remove majority-class instances that are part of a Tomek Link (a pair of instances of opposite classes who are each other's nearest neighbors). This cleans the decision boundary.

- Protocol - Validation: Always validate using a test set that reflects the original, real-world class distribution. Monitor per-class precision and recall, not just overall accuracy. Consider using balanced accuracy or MCC as your primary metric.

FAQ 3: My strategic data augmentations for protein sequences (e.g., residue substitution) are degrading model performance instead of improving it. How can I design biologically meaningful augmentations?

Answer: Arbitrary substitutions can break structural and functional constraints, introducing noise and harmful biases. Augmentations must respect evolutionary and biophysical principles.

- Solution - Evolutionary-Guided Augmentation: Use a position-specific scoring matrix (PSSM) or a statistical coupling analysis model to determine permissible substitutions at each residue position. Substitute residues only with those that have a high probability in the PSSM, ensuring the mutation is evolutionarily plausible.

- Protocol:

- Input your multiple sequence alignment (MSA) for the protein family of interest.

- Generate a PSSM using tools like

HMMERorPSI-BLAST. - For a given sequence, at a random position

i, sample a new residue from the distribution defined by the PSSM columni, favoring probabilities above a threshold (e.g., top 5). - Limit the augmentation rate to 1-2 substitutions per sequence on average to avoid drifting too far from the original.

- Checklist: Are your augmented sequences being evaluated by a downstream predictor (e.g., AlphaFold2 for structure stability)? Implement a filtering step to discard low-confidence augmented samples.

FAQ 4: How do I balance the use of all three strategies—Active Learning (AL), Under-Sampling (US), and Strategic Augmentation (SA)—in a single pipeline without introducing conflicting biases?

Answer: The key is to apply them in a staged, iterative manner, with continuous evaluation.

- Proposed Workflow Protocol:

- Initial Phase: Start with a small, balanced seed dataset. Apply Strategic Augmentation only to the minority classes to increase their robust representation.

- Active Learning Loop: Train a model on the current set. Use an acquisition function that weights both uncertainty and class balance (e.g., entropy-based querying per class).

- Curation of New Batch: For the newly selected batch from AL, which may be class-imbalanced, apply informed Under-Sampling on any over-represented majority class instances within that batch before annotation.

- Annotate & Add: Add the newly annotated, curated batch to the training pool.

- Re-balance & Re-augment: Periodically, after several AL cycles, re-assess the entire training pool's balance. Apply strategic under-sampling on the global majority class and targeted augmentation on the global minority class.

- Validation: Hold out a fully representative, untouched validation set for final model selection.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Implementing an Active Learning Loop for Protein Function Annotation

- Data Pool:

U= Large, unlabeled set of protein sequences.L= Small, initially labeled set (seed). - Model Selection: Choose a base predictor (e.g., a fine-tuned protein language model like ProtBERT).

- Acquisition Function: Define

a(x)= Predictive Entropy:a(x) = - Σ_c p(y=c|x) log p(y=c|x), wherecis the functional class. - Iteration:

- Train model on current

L. - For all

xinU, computea(x). - Select the

Binstances fromUwith the highesta(x). - (Optional) Apply diversity filtering (see FAQ 1).

- Obtain expert annotation for selected batch.

- Remove batch from

U, add toL.

- Train model on current

- Stopping Criterion: Loop until performance on a held-out validation set plateaus or annotation budget is exhausted.

Protocol 2: Informed Under-Sampling Using Tomek Links

- Input: Training set

Twith featuresXand labelsY, where class0is majority. - Distance Metric: Compute pairwise distances in embedded space (e.g., using ESM-2 embeddings). Normalize features.

- Identification: For each instance

iin class1(minority), find its nearest neighbornn(i). Ifnn(i)belongs to class0, and fornn(i), its nearest neighbor isi, then(i, nn(i))is a Tomek Link. - Removal: Remove all majority class instances (

nn(i)) that are part of any Tomek Link. - Output: Cleaned training set

T'.

Protocol 3: Evolutionary-Guided Data Augmentation for Proteins

- Input: A sequence

Sof lengthLbelonging to a known protein family. - MSA & PSSM: Retrieve or generate a deep MSA for the protein family. Build a PSSM of dimensions

20 x L(for 20 amino acids). - Substitution Probability: For each position

linS, the PSSM columnP_lgives the log-odds for each amino acid. - Augmentation Decision:

- For each sequence, sample a number

kfrom a Poisson distribution with λ=1.5 (target mutations per sequence). - Randomly select

kpositions inSwithout replacement. - For each selected position

l, sample a new amino acid from the distributionsoftmax(P_l * τ), whereτis a temperature parameter (τ < 1.0 to sharpen distribution). - Replace the original residue with the sampled one.

- For each sequence, sample a number

- Output: A set of augmented variant sequences

S'_1, S'_2, ....

Visualizations

Active Learning Loop for Protein Data Curation

Staged Data Curation Pipeline Workflow

Research Reagent Solutions

| Item / Solution | Function in Experiment | Example / Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Protein Language Model (Pretrained) | Generates contextual embeddings for sequences; serves as base for active learning classifier or feature extractor for clustering. | ESM-2 (650M params), ProtBERT. Use for sequence featurization. |

| Multiple Sequence Alignment (MSA) Tool | Generates evolutionary profiles essential for strategic, biologically-plausible data augmentation. | HMMER (hmmer.org), PSI-BLAST. Critical for building PSSMs. |

| Imbalanced-Learn Library | Provides implemented algorithms for informed under-sampling and over-sampling, ensuring reproducible methodology. | Python imbalanced-learn package. Includes TomekLinks, NearMiss, SMOTE. |

| ModAL Framework | Facilitates building active learning loops by abstracting acquisition functions and model querying. | Python modAL package. Integrates with scikit-learn and PyTorch. |

| Structural Stability Predictor | Filters augmented protein sequences by predicting potential destabilization, ensuring biophysical validity. | AlphaFold2 (local ColabFold), ESMFold. Predict structure/confidence. |

| Embedding Distance Metric | Measures similarity between protein sequences in embedding space for clustering and diversity sampling. | Cosine similarity or Euclidean distance on ESM-2 embeddings. |

| Annotation Platform Interface | Streamlines the expert-in-the-loop step of active learning by managing and recording batch annotations. | Custom REST API connected to LabKey, REDCap, or similar LIMS. |

Table 1: Comparison of Sampling Strategies on a Benchmark Protein Localization Dataset (10 classes, initial bias: 40% class 'Nucleus')

| Strategy | Final Balanced Accuracy | Minority Class (Lysosome) F1-Score | Avg. Expert Annotations Needed | Critical Parameter |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Random Sampling (Baseline) | 0.72 (±0.03) | 0.45 (±0.07) | 25,000 (full set) | N/A |

| Uncertainty Sampling (AL) | 0.81 (±0.02) | 0.68 (±0.05) | 8,500 | Batch Size = 250 |

| Uncert. + Diversity (AL) | 0.85 (±0.02) | 0.75 (±0.04) | 7,200 | Diversity Weight = 0.3 |

| Random Under-Sampling | 0.78 (±0.04) | 0.82 (±0.03) | 25,000 | Sampling Ratio = 0.5 |

| Tomek Links (US) | 0.83 (±0.02) | 0.80 (±0.03) | 25,000 | Distance Metric = Cosine |

| AL + Strategic US | 0.88 (±0.01) | 0.84 (±0.02) | 6,000 | US applied per AL batch |

| Full Pipeline (AL+US+SA) | 0.91 (±0.01) | 0.89 (±0.02) | 5,500 | Aug. Temp. (τ) = 0.8 |

Table 2: Impact of Strategic Augmentation Temperature (τ) on Model Performance

| Augmentation Temperature (τ) | Per-Sequence Mutations (Avg.) | Validation Accuracy | Structural Confidence (Avg. pLDDT) | Effect |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No Augmentation | 0.0 | 0.83 | N/A | Baseline |

| 0.2 (Very Conservative) | 1.1 | 0.85 | 89.2 | High confidence, low diversity |

| 0.8 (Recommended) | 1.4 | 0.88 | 86.5 | Good balance |

| 1.5 (High Diversity) | 2.3 | 0.81 | 74.1 | Lower confidence, noisy |

| Random Substitution | 1.5 | 0.76 | 62.3 | Biologically implausible, harmful |

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting & FAQs

This technical support center provides guidance for researchers implementing bias mitigation algorithms in the context of protein function prediction and annotation, specifically within a thesis on Addressing annotation biases in protein training data research.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: During adversarial debiasing, my primary classifier's performance collapses. The loss becomes unstable (NaN). What is the likely cause and solution? A: This is a common issue indicating an imbalance in the training dynamics between the primary model and the adversarial discriminator.

- Cause: The adversarial discriminator is becoming too powerful too quickly, providing excessively strong gradients that destabilize the primary model's weight updates.

- Solution: Implement a gradient reversal layer with a controlled scaling factor (λ). Start with a small λ (e.g., 0.1) and slowly increase it. Alternatively, use a two-time-scale update rule (TTUR), training the adversarial discriminator with a slower learning rate (e.g., 0.001) than the primary model (e.g., 0.01).

Q2: My bias-aware loss function (e.g., Group-DRO) leads to severe overfitting on the minority group. Validation performance drops after a few epochs. A: Overfitting to small, re-weighted groups is a key challenge.

- Cause: The loss function may be up-weighting a very small subset of data with high bias correlation, causing the model to memorize noise.

- Solution: Combine with robust regularization. Apply strong weight decay and dropout. Consider early stopping based on a held-out validation set that reflects the desired unbiased distribution. Data augmentation for the minority group (e.g., via stochastic protein sequence masking) can also help.

Q3: How do I quantify if my debiasing technique is working? My accuracy is unchanged, but I need to demonstrate bias reduction. A: Accuracy is an insufficient metric. You must measure bias metrics on a carefully constructed test set.

- Protocol: Create a "bias probe" test set where protein examples are paired or stratified by the suspected bias (e.g., sequence length, homology to a well-studied family, source organism). Calculate:

- Disparity in Performance: Difference in F1-score or AUROC between groups.

- Equality of Opportunity: Difference in true positive rates between groups.

- Predictive Parity: Difference in positive predictive values between groups.

- Solution: Track these metrics during training. Successful debiasing should show a reduction in these disparity scores with minimal loss in overall performance.

Q4: I suspect multiple overlapping biases in my protein data (e.g., taxonomic and experimental method). Can I use a multi-head adversarial debiasing setup? A: Yes, but architectural choices are critical to avoid conflicts.

- Cause: A single shared feature representation may not suffice to simultaneously deceive multiple adversarial discriminators for different bias attributes.

- Solution: Implement a multi-head adversarial network with projection. Use a shared encoder, then project features into separate subspaces before feeding to each bias-specific discriminator. This allows the model to learn to remove specific biases in different feature projections.

Experimental Protocols for Key Cited Experiments

Protocol 1: Evaluating Adversarial Debiasing for Taxonomic Bias

- Dataset Construction: From UniProt, select proteins with "enzyme" annotation. Create a biased training set by under-sampling proteins from fungal taxa (minority group). Create balanced validation/test sets.

- Model Architecture:

- Primary Classifier: CNN protein sequence encoder → 512D hidden layer → classification layer (enzyme/non-enzyme).

- Adversarial Discriminator: Gradient Reversal Layer (GRL) → 128D hidden layer → taxonomic group classifier (fungal/bacterial/archaeal).

- Training: Use TTUR. Primary classifier LR=0.01, Discriminator LR=0.001. λ for GRL annealed from 0 to 1 over epochs.

- Evaluation: Report primary task AUROC and Disparity in Performance (fungal vs. bacterial AUROC gap) on the balanced test set.

Protocol 2: Implementing a Bias-Aware Loss (Reduced Lagrangian Optimization)

- Bias Attribute Labeling: For each protein in the training set, label its "annotation source bias" (e.g., 1 if annotated via high-throughput experiment, 0 if via manual curation).

- Loss Formulation: Minimize the maximum loss across groups. Define groups g by bias label. The objective is: minθ maxg E(x,y)∈Ĝg[L(f_θ(x), y)].

- Optimization: Use the Group DRO algorithm with stochastic mirror descent. Update group weights q_g every k steps based on recent group losses.

- Validation: Monitor group-wise worst-case error on a validation set. Terminate training when this worst-case error plateaus.

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Debiasing Techniques on Protein Function Prediction (EC Number)

| Technique | Overall Accuracy (%) | Minority Group F1-Score (%) | Disparity (F1 Gap) | Training Time (Relative) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline (Cross-Entropy) | 88.7 | 65.2 | 28.5 | 1.0x |

| Adversarial Debiasing (GRL) | 87.1 | 78.9 | 12.3 | 1.8x |

| Group DRO Loss | 86.5 | 80.3 | 9.8 | 1.5x |

| Combined (DRO + Adv) | 86.0 | 82.1 | 7.9 | 2.2x |

Table 2: Impact of Taxonomic Debiasing on Downstream Drug Target Prediction

| Model | Novel Target Hit Rate (Bacterial) | Novel Target Hit Rate (Fungal) | Hit Rate Disparity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biased Pre-trained Embedding | 12.4% | 3.1% | 9.3 pp |

| Debiased Pre-trained Embedding | 10.8% | 7.9% | 2.9 pp |

pp = percentage points

Visualizations

Diagram 1: Adversarial Debiasing Architecture for Protein Data

Diagram 2: Workflow for Bias Evaluation & Mitigation

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Bias Mitigation Experiments |

|---|---|

| Stratified Protein Data Splits | Curated datasets (train/val/test) with documented distributions of bias attributes (taxonomy, sequence length, annotation type) for controlled evaluation. |

| Gradient Reversal Layer (GRL) | A connective layer that acts as an identity during forward pass but reverses and scales gradients during backpropagation, enabling adversarial training. |

| Group Distributionally Robust Optimization (DRO) | A PyTorch/TF-compatible loss function that minimizes the worst-case error over predefined data groups, directly targeting performance disparities. |

| Bias Probe Benchmark Suite | A collection of standardized test modules, each designed to stress-test a model's performance on a specific potential bias (e.g., Pfam-family hold-out clusters). |

| Sequence Masking Augmentation Tool | A script that applies random masking or substitution to protein sequences during training to artificially expand minority groups and reduce overfitting. |

| Disparity Metrics Logger | A training callback that computes and logs group-wise performance metrics (F1, TPR, PPV) after each epoch to track bias reduction progress. |

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Q1: Our model, trained on annotated protein-protein interaction (PPI) data, shows high performance on test sets but fails to predict novel interactions not represented in the training distribution. What strategies can we use to mitigate this annotation bias? A: This is a classic case of dataset bias where labeled data covers only a fraction of the true interactome. Implement the following protocol:

- Integrate Orthogonal Unlabeled Data: Source large-scale, unlabeled structural databases (e.g., AlphaFold DB, PDB) and protein co-complex data.

- Generate Pseudo-Labels: Use a pre-trained structure-based model (e.g., DeepMind's AlphaFold-Multimer) to predict interaction probabilities for unlabeled protein pairs. Apply a conservative confidence threshold (e.g., pLDDT > 80, ipTM > 0.7) to create a high-quality pseudo-labeled set.

- Semi-Supervised Training: Retrain your primary model using a combined loss:

L_total = L_supervised + λ * L_unsupervised, where the unsupervised loss is computed on the pseudo-labeled data. Start with λ=0.1 and gradually increase.

Q2: When using text mining from biomedical literature to expand training data, how do we handle contradictory or low-confidence assertions? A: Noise from text mining is a significant challenge. Employ a confidence-weighted integration framework.

- Extract Relations: Use an NLP tool (e.g., RELATION, BioBERT fine-tuned for relation extraction) to mine sentences for protein interactions.

- Assign Confidence Scores: For each extracted assertion, compute a confidence score

Cbased on:- NLP model probability.

- Sentence specificity (presence of specific interaction verbs like "binds," "phosphorylates").

- Publication frequency and recency.

- Filter and Integrate: Only add assertions with

C > T(a set threshold) to your training pool. Use the confidence score as a sample weight during model training to reduce the impact of noisy labels.

Q3: Our integration of interaction network data leads to over-smoothing in graph neural networks (GNNs), blurring distinctions between protein functions. How can we preserve local specificity? A: Over-smoothing occurs when nodes in a GNN become too similar after many propagation layers. Use a residual or jumping knowledge network architecture.

- Protocol: Implement a GNN with

klayers. Instead of using only the final node embeddings, concatenate the embeddings from each layer. This allows the classifier to access both local (early layers) and global (later layers) structural information. The formula for the final node representationh_vbecomes:h_v = CONCAT(h_v^(1), h_v^(2), ..., h_v^(k)), whereh_v^(l)is the embedding of nodevat layerl.

Q4: How can we quantitatively evaluate if our method has successfully reduced annotation bias, not just overfitted to new noise? A: Design a rigorous, multi-faceted evaluation split that separates the known from the unknown.

- Create Evaluation Sets:

- Temporal Holdout: Test on interactions discovered after the publication date of your training data sources.

- Functional Holdout: Test on proteins from a molecular function or pathway completely absent from training.

- Orthogonal Validation: Validate high-confidence predictions using an orthogonal method (e.g., validate computationally predicted interactions via surface plasmon resonance or yeast-two-hybrid assays on a subset).

- Track Key Metrics: Compare performance (AUC-ROC, Precision-Recall) across these holdout sets versus the standard benchmark. Successful bias reduction shows smaller performance gaps between benchmark and holdout sets.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of PPI Prediction Models with Unlabeled Data Integration

| Model Architecture | Training Data Source | Standard Test Set (AUC-ROC) | Temporal Holdout Set (AUC-ROC) | Functional Holdout Set (AUC-ROC) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline GCN | Curated PPI Databases Only | 0.92 | 0.65 | 0.58 |

| GCN + Structure Pseudo-Labels | Curated DB + AlphaFold DB Predictions | 0.91 | 0.78 | 0.75 |

| GCN + Text-Mined Assertions | Curated DB + Literature Mining | 0.89 | 0.72 | 0.70 |

| Hybrid GAT | Curated DB + AF DB + Literature | 0.93 | 0.82 | 0.81 |

GCN: Graph Convolutional Network; GAT: Graph Attention Network. Data is illustrative of current research trends.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Generating Structure-Based Pseudo-Labels for PPIs

- Input: A list of unlabeled protein pairs from a target proteome.

- Structure Prediction: For each pair (A, B), generate a complex structure using AlphaFold-Multimer v3 (localcolabfold or via API). Run 5 model predictions and 3 recycles.

- Scoring: Extract the predicted interface pTM (ipTM) and the average pLDDT of residues within 5Å of the interface.

- Thresholding: Assign a positive pseudo-label if

ipTM > 0.7ANDavg_pLDDT > 80. Assign a negative pseudo-label ifipTM < 0.4. - Output: A set of high-confidence positive and negative interaction pairs for semi-supervised training.

Protocol 2: Confidence-Weighted Integration of Text-Mined Interactions

- Corpus: Download PubMed abstracts and full-text articles relevant to your target proteins (e.g., via PubMed Central FTP).

- Relation Extraction: Process text through a fine-tuned BioBERT model trained on the PPI corpus (e.g., BioCreative VI). Extract (Protein1, Interaction, Protein2) triples.

- Confidence Scoring: Calculate final confidence

C = 0.5*P_model + 0.3*I_verb + 0.2*Pub_Score.P_model: Softmax probability from the NLP model.I_verb: 1.0 for direct verbs ("binds"), 0.5 for indirect ("regulates"), 0.1 for unclear.Pub_Score: Min-max normalized count of supporting papers from the last 5 years.

- Curation: Manually review a random sample of assertions at different confidence levels to calibrate the threshold

T(e.g., T=0.65).

Visualizations

Title: Semi-Supervised Learning Workflow to Counteract Annotation Bias

Title: Multi-View Data Integration Pipeline for Protein Analysis

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Tools for Debiasing Protein Data Research

| Item | Function & Role in Addressing Bias |

|---|---|

| AlphaFold DB / AlphaFold-Multimer | Provides high-quality predicted protein structures and complexes for millions of proteins, enabling the generation of structure-based pseudo-labels to fill gaps in experimental interaction data. |

| ColabFold (LocalColabFold) | Accessible, accelerated platform for running AlphaFold-Multimer, crucial for generating custom interaction predictions for specific protein pairs of interest. |

| BioBERT / PubMedBERT | Pre-trained language models fine-tuned for biomedical NLP, essential for mining protein interactions and functional annotations from vast, unlabeled literature corpora. |

| PyTorch Geometric / DGL | Graph Neural Network libraries that facilitate the building of models that integrate protein interaction networks, sequence, and structural features in a unified framework. |

| BioGRID / STRING / IID | Comprehensive protein interaction databases (containing both curated and predicted data) used as benchmarks, sources for unlabeled network context, and for constructing holdout evaluation sets. |

| Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) | An orthogonal biophysical validation technique (e.g., Biacore systems) used to experimentally confirm a subset of computationally predicted novel interactions, verifying model generalizability. |

This technical support center provides troubleshooting guidance for common issues encountered while constructing protein training sets, a critical step in mitigating annotation biases as part of broader research efforts.

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Q1: My dataset shows high sequence similarity clusters after redundancy reduction. How do I ensure it doesn't introduce taxonomic bias?

A: High clustering often indicates over-representation of certain protein families or organisms. First, analyze the taxonomic distribution of your clusters. Implement a stratified sampling approach during the clustering step, setting a maximum number of sequences per genus or family. Use tools like MMseqs2 linclust with the --max-accept parameter per taxon, rather than a global similarity cutoff alone.

Q2: I am getting poor model generalization on under-represented protein families. What preprocessing steps can address this? A: This is a classic symptom of annotation bias. Proactively augment your training set for these families. Use remote homology detection tools (e.g., HMMER, JackHMMER) to find distant, validated homologs from under-sampled taxa. Consider generating synthetic variants via carefully crafted multiple sequence alignment (MSA) profiles and in-silico mutagenesis, focusing on conservative substitutions.

Q3: How do I validate that my train/test split effectively avoids data leakage from homology? A: Perform an all-vs-all BLAST (or DIAMOND) search between your training and test/validation sets. Use the following protocol:

- Create a BLAST database from your test set.

- Use your training set as the query.

- Apply a strict E-value threshold (e.g., 1e-3). Any significant hit indicates potential leakage.

- Re-assign leaking sequences to the same set (train or test) to maintain separation.

Q4: What is the best practice for handling ambiguous or missing structural data in a sequence-based training set? A: Do not silently discard these entries, as it may bias your set. Create a tiered dataset:

- Tier 1: High-confidence sequences with experimental annotations.

- Tier 2: Sequences with computationally inferred (e.g., AlphaFold2) structures or lower-confidence annotations. Clearly flag the annotation source and confidence score in your dataset metadata. Train initial models on Tier 1 only, then use them to evaluate performance on Tier 2 to assess bias impact.

Table 1: Common Redundancy Reduction Tools & Their Impact on Bias

| Tool/Method | Typical Threshold | Primary Use | Bias Mitigation Feature |

|---|---|---|---|

| CD-HIT | 0.6-0.9 seq identity | Fast clustering | -g 1 (more accurate) helps, but no taxonomic control. |

| MMseqs2 | 0.5-1.0 seq/lin identity | Large-scale clustering | --taxon-list & --stratum options for controlled sampling. |

| PISCES | 0.7-0.9 seq identity, R-factor | High-quality structural sets | Chain quality filters reduce experimental method bias. |

| Custom Pipeline | Variable | Tailored control | Integrate ETE3 toolkit for explicit phylogenetic balancing. |

Table 2: Impact of Preprocessing Steps on Dataset Composition

| Processing Step | Avg. Sequence Reduction | Common Risk of Introduced Bias | Recommended Check |

|---|---|---|---|

| Initial Quality Filtering | 5-15% | Loss of low-complexity/transmembrane regions. | Compare domain architecture (Pfam) distribution pre/post. |

| Redundancy Reduction @70% | 40-60% | Over-representation of well-studied taxa. | Plot taxonomic rank frequency (e.g., Phylum level). |

| Splitting by Sequence Identity | N/A | Family-level data leakage. | All-vs-all BLAST between splits (see Q3 protocol). |

| Annotation Harmonization | 0-10% | Propagation of legacy annotation errors. | Benchmark against a small, manually curated gold standard. |

Experimental Protocol: Creating a Phylogenetically Balanced Training Set

Objective: Generate a non-redundant protein training set that minimizes taxonomic annotation bias.

Materials:

- Initial raw sequence dataset (e.g., from UniProt).

- High-performance computing cluster or server.

- Software: MMseqs2, DIAMOND, ETE3 toolkit, custom Python/R scripts.

Methodology:

- Initial Filtering: Retrieve sequences with desired evidence levels (e.g., "Reviewed" only). Filter out fragments (length < 50 aa).

- Taxonomic Annotation: Assign a consistent taxonomy to each sequence using the

ETE3NCBI Taxonomydatabase. - Clustering with Constraints: Use

MMseqs2 easy-clusterwith identity threshold (e.g., 0.7). Crucially, first split the input by a high-level taxon (e.g., Phylum). Cluster each phylum-specific file separately, using the same threshold. This prevents dominant phyla from overwhelming clusters. - Representative Selection: From each cluster, select the representative sequence. If multiple, choose the one with the highest-quality annotation (e.g., experimental evidence).

- Final Balance Check: Use

ETE3to visualize the taxonomic tree of the selected representatives. Manually inspect for glaring over/under-representation and subsample if necessary. - Train/Test/Validation Split: Perform splitting within each major taxonomic group (e.g., Class level) using a random 80/10/10 partition. This ensures all groups are represented in all splits.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Tools for Bias-Aware Preprocessing

| Item | Function | Example/Version |

|---|---|---|

| MMseqs2 | Ultra-fast clustering & searching. Enables taxonomic-stratified processing. | MMseqs2 Suite (v14.7e284) |

| ETE3 Toolkit | Programming library for analyzing, visualizing, and manipulating phylogenetic trees. Critical for taxonomic analysis. | ETE3 (v3.1.3) |

| DIAMOND | Accelerated BLAST-compatible local sequence aligner. Essential for leakage checks. | DIAMOND (v2.1.8) |

| HMMER Suite | Profile hidden Markov models for sensitive remote homology detection. Used to find distant members of under-represented families. | HMMER (v3.3.2) |

| Pandas / Biopython | Data manipulation and parsing of biological file formats (FASTA, GenBank, etc.). | Pandas (v1.5.3), Biopython (v1.81) |

| Jupyter Lab | Interactive computing environment for prototyping preprocessing scripts and visualizing distributions. | Jupyter Lab (v4.0.6) |

| Custom Curation Gold Standard | A small, manually verified set of sequences/structures for benchmarking annotation quality. | e.g., 100+ diverse proteins from PDB & literature |

Workflow & Pathway Visualizations

Title: Pipeline for Phylogenetically Balanced Protein Set Creation

Title: Protocol to Validate No Homology Leakage in Data Splits

Beyond the Benchmark: Troubleshooting Bias in Real-World Model Deployment

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guide: Model Validation Errors

Issue 1: High performance on held-out test sets but catastrophic failure in real-world validation or wet-lab experiments.

- Root Cause Analysis: The model's test data is likely sampled from the same biased annotation source as the training data, allowing the model to learn annotation artifacts instead of underlying biological principles.