Semi-Rational Protein Design: Bridging Computational Modeling and Experimental Science for Next-Generation Therapeutics

This article provides a comprehensive overview of semi-rational protein design, a powerful methodology that synergistically combines computational modeling with experimental screening to engineer proteins with novel or enhanced functions.

Semi-Rational Protein Design: Bridging Computational Modeling and Experimental Science for Next-Generation Therapeutics

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of semi-rational protein design, a powerful methodology that synergistically combines computational modeling with experimental screening to engineer proteins with novel or enhanced functions. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational principles of moving beyond traditional directed evolution. The scope covers key computational tools and strategies for designing high-quality, small libraries, addresses common challenges and optimization techniques, and validates the approach through comparative analysis with other methods. The article concludes by examining the transformative impact of integrating artificial intelligence and advanced data-driven approaches on the future of protein engineering in biomedicine.

Beyond Directed Evolution: The Principles and Power of Semi-Rational Design

Semi-rational protein design represents a powerful hybrid methodology that strategically combines elements of rational design and directed evolution to accelerate the engineering of improved biocatalysts. This approach utilizes computational and bioinformatic analyses to identify promising "hotspot" residues for mutagenesis, creating smart libraries that are significantly smaller yet enriched with functional variants compared to traditional random mutagenesis libraries [1] [2]. By focusing experimental efforts on limited sets of residues predicted to be functionally important, semi-rational design dramatically reduces the experimental burden of library screening while maintaining a broad exploration of sequence space at targeted positions [3]. This methodology has transformed protein engineering from a largely discovery-based process toward a more hypothesis-driven discipline, enabling researchers to efficiently tailor enzymes for industrial applications including biocatalysis, therapeutics, and biomaterial development [1] [3].

The fundamental advantage of semi-rational design lies in its balanced approach. While traditional directed evolution requires creating and screening extremely large libraries (often millions of variants) through iterative cycles of random mutagenesis, and pure rational design demands complete structural and mechanistic understanding to predict effective mutations, the semi-rational pathway navigates between these extremes [4] [5]. It acknowledges the limitations in our current ability to perfectly predict protein behavior while leveraging available structural and evolutionary information to make informed decisions about which regions of sequence space to explore experimentally [6]. This practical compromise has proven exceptionally effective, with many successful engineering campaigns requiring the evaluation of fewer than 1000 variants to achieve significant improvements in enzyme properties such as stability, activity, and enantioselectivity [1] [2].

Conceptual Framework and Key Principles

Theoretical Foundations

Semi-rational design operates on the principle that not all amino acid positions contribute equally to specific protein functions. By identifying and targeting evolutionarily variable sites or structurally strategic positions, researchers can create focused libraries that sample a higher proportion of beneficial mutations [1] [5]. This approach recognizes that natural evolution has already explored certain sequence variations across protein families, information that can be harnessed through analysis of homologous sequences [1]. The methodology further acknowledges that proteins possess modular features where specific regions often control distinct properties, allowing for targeted optimization of particular functions without completely random exploration [6].

The theoretical framework incorporates both sequence-based and structure-based principles. From a sequence perspective, positions that show variation across homologs but maintain structural constraints represent potential engineering targets [5]. From a structural perspective, residues lining substrate access tunnels, forming active site walls, or located at domain interfaces often control key catalytic properties even when they don't participate directly in chemistry [1] [6]. This understanding enables the strategic selection of residues for mutagenesis based on their potential influence on the desired function, whether it be substrate specificity, enantioselectivity, or thermostability [6] [5].

Comparison with Traditional Approaches

Table 1: Comparison of Protein Engineering Strategies

| Feature | Directed Evolution | Rational Design | Semi-Rational Design |

|---|---|---|---|

| Library Size | Very large (10⁴-10⁶ variants) | Small (often <10 variants) | Focused (10²-10⁴ variants) |

| Structural Knowledge Required | Minimal | Extensive | Moderate |

| Computational Requirements | Low | High | Moderate to High |

| Experimental Throughput Needed | Very high | Low | Moderate |

| Mutation Strategy | Random across entire gene | Specific predetermined mutations | Targeted randomization at selected positions |

| Success Rate | Low but broad | High when structure-function well understood | Higher than directed evolution |

Semi-rational design occupies a strategic middle ground between two established protein engineering paradigms. Unlike traditional directed evolution, which relies on random mutagenesis of the entire gene and high-throughput screening of very large libraries, semi-rational approaches incorporate prior knowledge to create smaller, smarter libraries [4] [5]. This significantly reduces the screening burden while increasing the likelihood of identifying improved variants [1]. Conversely, unlike pure rational design that requires complete structural and mechanistic understanding to predict specific point mutations, semi-rational methods allow for limited randomization at targeted positions, accommodating gaps in our knowledge of structure-function relationships [6] [5].

The key advantage of semi-rational design emerges from this balanced approach. While rational design can be limited by imperfect structural knowledge and directed evolution by the vastness of sequence space, semi-rational design uses available information to constrain the search space to promising regions [1] [2]. This enables researchers to navigate protein sequence landscapes more efficiently, often achieving significant improvements in fewer iterative cycles and with substantially less screening effort [4]. The methodology is particularly valuable when engineering complex enzyme properties like enantioselectivity, where subtle changes in active site geometry can dramatically influence catalytic outcomes [6] [5].

Computational Tools and Methods

Sequence-Based Analysis Tools

Sequence-based methods leverage evolutionary information to identify promising target residues for protein engineering. Multiple sequence alignment (MSA) of homologous proteins helps identify conserved and variable positions, with "back-to-consensus" mutations often improving stability [5]. The 3DM database system automates superfamily analysis by integrating sequence and structure data from GenBank and PDB, allowing researchers to quickly identify evolutionarily allowed substitutions at specific positions [1]. This approach proved highly effective in engineering Pseudomonas fluorescens esterase, where a library designed with 3DM guidance yielded variants with 200-fold improved activity and significantly enhanced enantioselectivity, outperforming controls with random or evolutionarily disallowed substitutions [1].

The HotSpot Wizard server represents another powerful sequence-based tool that combines evolutionary information with structural data to create mutability maps for target proteins [1]. This web server performs extensive sequence and structure database searches integrated with functional data to recommend positions for mutagenesis, successfully guiding the engineering of haloalkane dehalogenase from Rhodococcus rhodochrous for improved catalytic activity [1]. These sequence-based tools are particularly valuable when high-quality structural information is limited, as they can identify functionally important residues based solely on evolutionary patterns.

Structure-Based Analysis Tools

When high-resolution structures are available, structure-based tools provide powerful platforms for identifying engineering targets. CAVER software analyzes protein tunnels and channels, identifying residues that control substrate access or product egress [6]. This approach helped explain and further improve haloalkane dehalogenase variants, where beneficial mutations optimized access tunnels rather than directly modifying the active site [1]. YASARA offers a user-friendly interface for structure visualization, hotspot identification, and molecular docking, with built-in capabilities for homology modeling when experimental structures are unavailable [6].

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations provide dynamic information beyond static structures, identifying flexible regions and conformational changes relevant to catalysis [6]. MD simulations have proven valuable for understanding the structural basis of enantioselectivity and for identifying distal mutations that influence enzyme function through allosteric effects or dynamic networks [6] [5]. For example, MD simulations of phenylalanine ammonia lyase revealed how loop flexibility controls reaction specificity, enabling engineering to alter enzyme function [6].

Advanced Computational Design Frameworks

Rosetta Design represents a comprehensive computational framework for enzyme redesign and de novo enzyme design [1] [6]. Its algorithm involves identifying optimal geometries for transition state stabilization (theozymes), searching for compatible protein scaffolds (RosettaMatch), and optimizing the active site pocket (RosettaDesign) [6]. This approach has successfully created novel enzymes for non-biological reactions, including Diels-Alderase catalysts [1]. The FRESCO (Framework for Rapid Enzyme Stabilization by Computational Libraries) pipeline enables computational prediction of stabilizing mutations, generating virtual libraries that are screened in silico before experimental validation [6].

Machine learning approaches are emerging as powerful tools for predicting sequence-function relationships. One study demonstrated that a group-wise sparse learning algorithm could predict microbial rhodopsin absorption wavelengths from amino acid sequences with an average error of ±7.8 nm, additionally identifying previously unknown color-tuning residues [7]. Such data-driven methods become increasingly powerful as experimental datasets grow, offering complementary approaches to physics-based modeling.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol 1: Coevolutionary Analysis and Multidimensional Virtual Screening (Co-MdVS)

The Co-MdVS strategy represents an advanced semi-rational protocol that combines coevolutionary analysis with multi-parameter computational screening to identify stabilizing mutations [8].

Step-by-Step Procedure

Sequence Collection and Alignment: Collect homologous sequences of the target enzyme (e.g., nattokinase) from public databases. Perform multiple sequence alignment using tools like ClustalW or MUSCLE.

Coevolutionary Analysis: Identify coevolving residue pairs using direct coupling analysis (DCA) or similar methods. These pairs represent evolutionarily correlated positions that likely influence protein stability.

Virtual Library Construction: Create a virtual mutation library containing single and double mutants at identified coevolutionary positions. For nattokinase, this generated 7980 virtual mutants [8].

Multidimensional Virtual Screening:

- Calculate folding free energy changes (ΔΔG) using tools like FoldX or Rosetta.

- Perform molecular dynamics simulations to determine dynamic parameters: root mean square deviation (RMSD), radius of gyration (Rg), and hydrogen bond counts.

- Screen mutants based on combined criteria: negative ΔΔG, reduced RMSD and Rg, increased hydrogen bonds compared to wild-type.

Experimental Validation: Select top-ranked mutants (e.g., 8 double mutants for nattokinase) for experimental characterization of thermostability, activity, and expression [8].

Iterative Combination: Combine beneficial mutations from initial hits and repeat screening if necessary. For nattokinase, this process yielded a final variant (M6) with a 31-fold increased half-life at 55°C [8].

Applications and Outcomes

This protocol successfully enhanced nattokinase robustness, with the optimal mutant M6 exhibiting significantly improved thermostability, acid resistance, and catalytic efficiency with different substrates [8]. The strategy was validated on other enzymes including L-rhamnose isomerase and PETase, demonstrating its general applicability [8].

Protocol 2: Sequence-Based Hotspot Identification and Saturation Mutagenesis

This protocol utilizes evolutionary information to identify target positions for saturation mutagenesis, particularly effective when structural data is limited.

Step-by-Step Procedure

Multiple Sequence Alignment: Compile homologous sequences (dozens to thousands) representing functional diversity within the enzyme family.

Conservation and Variability Analysis: Identify positions showing either high conservation (potential key functional residues) or high variability (potential specificity-determining residues).

Target Selection: Select 3-5 positions based on conservation patterns and proximity to active site or substrate binding regions.

Library Construction: Perform site-saturation mutagenesis at selected positions using degenerate codons (e.g., NNK codons) to create libraries of ~3000 variants.

Screening and Characterization: Screen for desired properties (activity, selectivity, stability). Isolate improved variants and sequence to identify beneficial substitutions.

Iterative Optimization: Combine beneficial mutations or perform additional rounds of saturation mutagenesis at newly identified hotspots.

Applications and Outcomes

This approach successfully engineered Pseudomonas fluorescens esterase for improved enantioselectivity, identifying variants with 200-fold improved activity and significantly enhanced stereoselectivity through mutations at just four targeted positions [1]. Similarly, engineering Bacillus-like esterase (EstA) for activity toward tertiary alcohol esters involved identifying a non-conserved position in the oxyanion hole (GGS instead of conserved GGG), with a single mutation (S to G) improving conversion by 26-fold [5].

Application Notes and Case Studies

Quantitative Results from Semi-Rational Engineering

Table 2: Representative Results from Semi-Rational Protein Engineering

| Target Enzyme | Engineering Goal | Methodology | Library Size | Key Results | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nattokinase | Improve thermostability | Co-MdVS | 8 double mutants screened | 31-fold increase in half-life at 55°C | [8] |

| Pseudomonas fluorescens esterase | Enhance enantioselectivity | 3DM analysis & SSM | ~500 variants | 200-fold activity improvement, 20-fold enantioselectivity enhancement | [1] |

| Haloalkane dehalogenase (DhaA) | Increase catalytic activity | HotSpot Wizard & MD simulations | ~2500 variants | 32-fold improved activity by restricting water access | [1] |

| Bacillus-like esterase (EstA) | Activity toward tertiary alcohol esters | MSA & site-directed mutagenesis | 1 variant | 26-fold improved conversion | [5] |

| nanoFAST protein | Expand color palette | Rational mutagenesis & fluorogen screening | 24 protein variants | Enabled red and green fluorogens in addition to original orange | [9] |

| Glutamate dehydrogenase (PpGluDH) | Enhance reductive amination activity | MSA & site-directed mutagenesis | 6 variants | 2.1-fold increased activity while maintaining soluble expression | [5] |

Case Study: Engineering Nattokinase Robustness

Nattokinase (NK), a fibrinolytic enzyme with therapeutic potential, suffers from limited stability at high temperatures and under acidic conditions. Traditional engineering approaches faced challenges due to trade-offs between stability and activity [8]. Application of the Co-MdVS strategy enabled precise redesign focusing on coevolutionary residue pairs:

Experimental Design: Researchers identified 28 coevolutionary residue pairs from analysis of 634 homologous sequences. They constructed a virtual library of 7980 mutants and applied multidimensional screening including ΔΔG calculations, RMSD, Rg, and hydrogen bond analysis [8].

Key Outcomes: From initial screening of just 8 double mutants, researchers identified several with improved properties. Iterative combination yielded mutant M6 with:

- 31-fold longer half-life at 55°C

- Enhanced acid resistance

- Improved catalytic efficiency (kcat/KM)

- Reduced flexibility in thermal and acid-sensitive regions confirmed by MD simulations [8]

This case demonstrates how semi-rational approaches can efficiently break stability-activity trade-offs by targeting evolutionarily correlated residues with precision.

Case Study: Expanding the nanoFAST Color Palette

The nanoFAST protein, smallest fluorogen-activating protein tag (98 amino acids), originally bound only a single orange fluorogen. Researchers employed semi-rational design to expand its color versatility for bioimaging:

Experimental Design: Based on structural knowledge and previous directed evolution results from the parent FAST protein, researchers introduced specific mutations at key positions (E46Q, position 52 variations, and entrance residues 68-69). They screened 24 protein variants against a library of fluorogenic compounds including arylidene-imidazolones and arylidene-rhodanines [9].

Key Outcomes: The E46Q mutation proved critical for expanding fluorogen range. Modified nanoFAST variants could now utilize red and green fluorogens in addition to the original orange, enabling multicolor imaging applications with this minimal tag. This successful engineering demonstrates how semi-rational approaches can efficiently expand protein functionality by combining structural insights with limited experimental screening [9].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Semi-Rational Design

| Reagent/Resource | Type | Function in Semi-Rational Design | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3DM Database | Bioinformatics platform | Superfamily analysis for evolutionarily allowed substitutions | Engineering esterase enantioselectivity [1] |

| HotSpot Wizard | Web server | Identification of mutable positions combining sequence and structure data | Haloalkane dehalogenase engineering [1] |

| Rosetta Software Suite | Computational design platform | De novo enzyme design, transition state stabilization, scaffold matching | Diels-Alderase design [1] [6] |

| CAVER | Structure analysis tool | Identification and analysis of substrate access tunnels and channels | Engineering substrate access in dehalogenases [6] |

| YASARA | Molecular modeling suite | Structure visualization, homology modeling, molecular docking | Residue interaction analysis and mutation prediction [6] |

| Site-Saturation Mutagenesis Kits | Experimental reagent | Creating all possible amino acid substitutions at targeted positions | Focused library generation [4] |

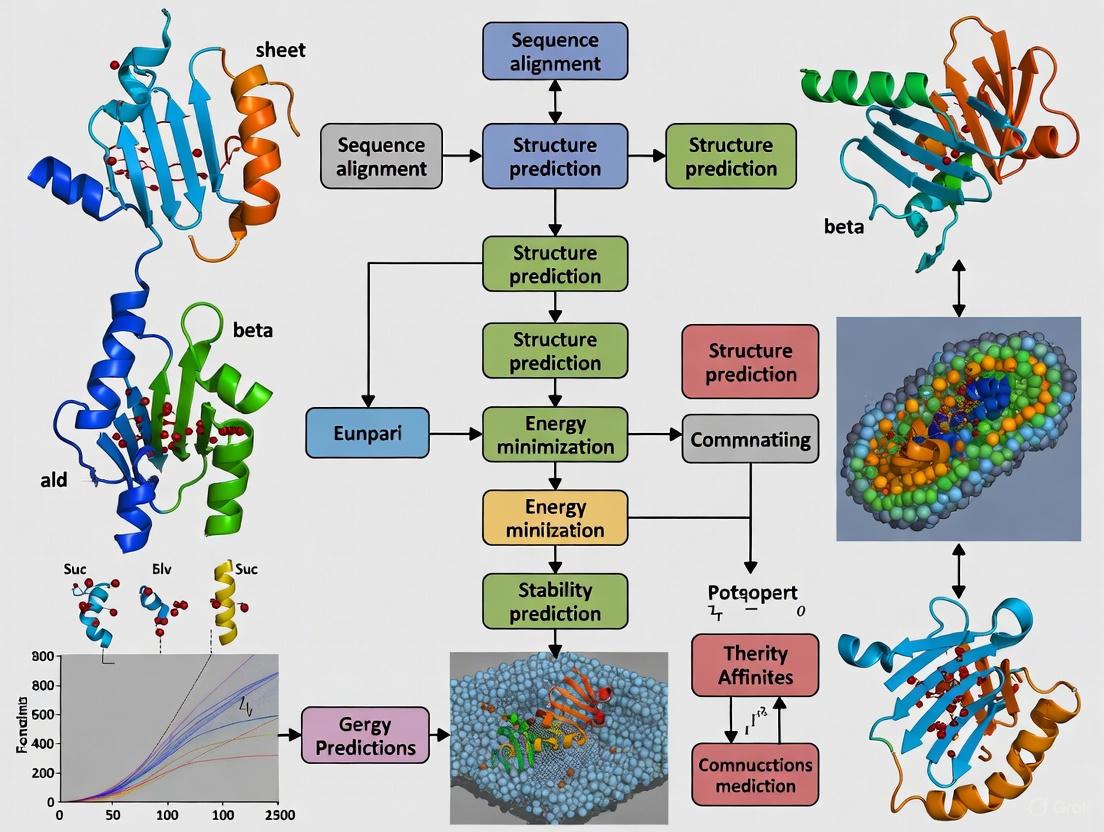

Workflow Visualization

Semi-Rational Design Workflow: This diagram illustrates the iterative cycle of computational analysis and experimental validation that characterizes semi-rational protein design.

Co-MdVS Strategy: This diagram outlines the coevolutionary analysis and multidimensional virtual screening protocol for enhancing enzyme robustness, demonstrating the high efficiency of this semi-rational approach.

Semi-rational protein design has established itself as a highly efficient methodology that successfully bridges the gap between purely computation-driven rational design and screening-intensive directed evolution. By leveraging the growing wealth of protein structural data, evolutionary information, and advanced computational tools, this approach enables researchers to navigate the vastness of protein sequence space with unprecedented efficiency [1] [8]. The continued development of computational methods, particularly in machine learning and molecular dynamics, promises to further enhance the precision and predictive power of semi-rational design [7] [8].

Future advances in semi-rational design will likely focus on improved prediction of allosteric effects and long-range interactions, more accurate modeling of conformational dynamics, and better integration of high-throughput experimental data to refine computational models [1] [6]. As these methods mature, semi-rational approaches will play an increasingly central role in engineering enzymes for sustainable chemistry, therapeutic applications, and novel biomaterials, accelerating the development of biocatalysts tailored to specific industrial needs [3] [8]. The integration of semi-rational design with automated laboratory systems and high-throughput characterization techniques will further streamline the protein engineering pipeline, making customized enzyme development more accessible and efficient across diverse applications.

The Shift from Large Combinatorial Libraries to Small, Functionally-Rich Libraries

The field of protein engineering is undergoing a significant transformation, moving away from brute-force screening of massive combinatorial libraries toward the design of focused, functionally enriched libraries. This paradigm shift is driven by the recognition that randomly generated sequences rarely fold into well-ordered proteinlike structures, making conventional approaches inefficient for discovering novel proteins with desired activities [10]. Traditional saturation mutagenesis techniques, which use degenerate codons to encode all 20 amino acids, explore only a tiny fraction of possible sequence space while consuming substantial experimental resources [11] [1]. In contrast, semi-rational design strategies leverage computational modeling, structural biology insights, and artificial intelligence to create smaller, smarter libraries highly enriched for stable, functional variants [1]. This approach has become increasingly viable due to advances in bioinformatics and the growing availability of detailed enzyme crystal structures, enabling researchers to preselect promising target sites and limited amino acid diversity [12] [1]. The result is dramatically improved efficiency in protein engineering campaigns, often requiring fewer iterations and eliminating the need for ultra-high-throughput screening methods while providing an intellectual framework to predict and rationalize experimental findings [1].

Key Methodological Approaches

Sequence-Based Design Using Evolutionary Information

Sequence-based methods leverage evolutionary information to identify functional hotspots and acceptable amino acid substitutions. By analyzing multiple sequence alignments (MSAs) and phylogenetic relationships among homologous proteins, researchers can identify evolutionarily conserved positions and residues with high natural variability [1]. Tools like the 3DM database systematically integrate protein sequence and structure data from GenBank and the PDB to create comprehensive alignments of protein superfamilies, enabling researchers to identify correlated mutations and conservation patterns [1]. Similarly, the HotSpot Wizard server combines information from extensive sequence and structure database searches with functional data to create mutability maps for target proteins [1]. These approaches were successfully applied to engineer Pseudomonas fluorescens esterase, where a library focused on evolutionarily allowed substitutions significantly outperformed controls with random or non-allowed substitutions, yielding variants with higher frequency and superior catalytic performance [1].

Structure-Based Computational Design

Structure-based methods utilize protein three-dimensional structural information to design optimized libraries. The Structure-based Optimization of Combinatorial Mutagenesis (SOCoM) method exemplifies this approach, using structural energies to optimize combinatorial mutagenesis libraries [13]. SOCoM employs cluster expansion (CE) to transform structure-based evaluation into a function of amino acid sequence that can be efficiently assessed and optimized, choosing both positions and substitutions that maximize library quality [13] [11]. This method enables the design of libraries enriched with stable variants while covering substantial sequence diversity. In application case studies targeting green fluorescent protein, β-lactamase, and lipase A, SOCoM-designed libraries achieved variant energies comparable to or better than previous library design efforts while maintaining greater diversity than representative random library approaches [13]. Another structure-based strategy involves analyzing and engineering access tunnels to enzyme active sites, as demonstrated with Rhodococcus rhodochrous haloalkane dehalogenase (DhaA), where mutations affecting product release pathways led to 32-fold improved activity [1].

Binary Patterning for De Novo Protein Design

The binary code strategy represents a powerful approach for designing novel proteins from scratch by specifying the pattern of polar and nonpolar residues while varying their precise identities [10]. This method constrains sequences to favor the formation of amphiphilic secondary structures that can anneal into well-defined tertiary structures. For α-helical bundles, polar and nonpolar residues are arranged with a periodicity of 3.6 residues per turn, while for β-sheets, residues alternate with a periodicity of 2.0 [10]. Combinatorial diversity is introduced using degenerate genetic codons: polar residues (Lys, His, Glu, Gln, Asp, Asn) are encoded by VAN, and nonpolar residues (Met, Leu, Ile, Val, Phe) by NTN [10]. This approach has successfully produced well-ordered structures, cofactor binding, catalytic activity, self-assembled monolayers, amyloid-like nanofibrils, and protein-based biomaterials [10]. The solution structure of a binary-patterned four-helix bundle (S-824) confirmed the formation of a nativelike protein with proper segregation of polar and nonpolar residues, despite the combinatorial approach not explicitly designing specific side-chain interactions [10].

Table 1: Comparison of Semi-Rational Library Design Strategies

| Method | Key Principle | Library Size | Advantages | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sequence-Based Design | Evolutionary conservation and variability analysis from multiple sequence alignments | Small to medium (~100-1000 variants) | Leverages natural evolutionary optimization; identifies functionally important positions | Esterase enantioselectivity improvement [1]; Prolyl endopeptidase stability enhancement [1] |

| Structure-Based Design (SOCoM) | Cluster expansion of structural energies for library optimization | Small to very large (thousands to billions) | Directly optimizes for structural stability; enables design of large diverse libraries with high quality | GFP core libraries [13]; β-lactamase and lipase A active sites [13] |

| Binary Patterning | Polar/nonpolar residue patterning for secondary structure control | Very large (combinatorial diversity) | Enables de novo protein design; produces well-folded structures without existing templates | Four-helix bundle proteins [10]; Amyloid-like nanofibrils [10] |

| Active Site Optimization | Molecular dynamics and docking simulations to guide active site mutations | Small (~10-100 variants) | Directly targets catalytic efficiency and substrate specificity | Terpene synthase engineering [12]; α-L-rhamnosidase tolerance enhancement [14] |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Structure-Based Library Design Using SOCoM

The SOCoM protocol enables optimization of combinatorial mutagenesis libraries based on structural energies [13]:

Define Library Design Space: Identify potential mutation positions and possible amino acid substitutions at each position, typically excluding proline and cysteine to avoid backbone strain and disulfide complications.

Cluster Expansion Transformation: Use CE to convert the structure-based energy function into a efficient sequence-based evaluation method, dramatically reducing computation time without significant accuracy loss.

Library Representation: Specify libraries as sets of "tubes," where each tube defines amino acid choices at a particular position. The total library size equals the product of individual tube sizes.

Library Optimization: Employ integer linear programming to select optimal libraries based on library-averaged CE energy scores without explicit enumeration of all variants.

Library Construction and Screening: Synthesize and express the designed library, then screen for desired functional properties.

This protocol was successfully applied to design GFP libraries targeting core positions (57-72), resulting in variants with favorable Rosetta energies while maintaining structural integrity [13].

Semi-Rational Engineering of α-L-Rhamnosidase for Alkaline Tolerance

A recent study demonstrated a comprehensive semi-rational approach to enhance the alkaline tolerance of Metabacillus litoralis C44 α-L-rhamnosidase (MlRha4) for industrial production of isoquercetin [14]:

Random Mutagenesis and Analysis: Perform error-prone PCR to generate an initial mutant library (350 variants). Identify improved variants and, importantly, analyze completely inactive mutants to understand critical structural constraints.

Reverse Mutagenesis: Implement reverse mutations at critical positions identified from inactive mutants (e.g., D482R and T334R), which surprisingly yielded higher enzymatic activity than wild-type.

Semi-Rational Design: Employ three parallel strategies:

- Surface Charge Engineering: Modify surface residues to enhance alkaline stability.

- Substrate Pocket Saturation: Target residues within 6Å of the substrate for saturation mutagenesis.

- Stability Enhancement: Reduce unfolding free energy through structure-guided mutations.

Combinatorial Mutagenesis: Combine beneficial mutations to generate superior variants like R-28 (K89R-K70R-E475D) with improved alkali tolerance, stability, and activity.

Molecular Dynamics Validation: Perform MD simulations to understand structural basis for improved performance, confirming enhanced compactness and binding free energy.

The resulting R-28 mutant demonstrated significantly improved production of isoquercetin across a wide range of rutin concentrations (10-300 g/L), addressing a major industrial challenge [14].

Diagram 1: Semi-rational protein engineering workflow highlighting the iterative process from target analysis to lead identification.

Binary Patterned Library Construction for De Novo Proteins

The binary code strategy for creating novel protein structures follows this protocol [10]:

Scaffold Design: Select a target protein architecture (e.g., four-helix bundle, β-sheet) and an appropriate sequence length.

Binary Pattern Specification: Define the precise pattern of polar (○) and nonpolar (•) residues matching the structural periodicity of the target:

- For α-helices: Use 3.6-residue repeat (e.g., ○•○○••○○•○○••○)

- For β-strands: Use alternating pattern (e.g., ○•○•○•○)

Degenerate Codon Design: Encode polar positions with VAN codons (specifying Lys, His, Glu, Gln, Asp, Asn) and nonpolar positions with NTN codons (specifying Met, Leu, Ile, Val, Phe).

Gene Library Synthesis: Construct synthetic genes using degenerate oligonucleotides and clone into appropriate expression vectors.

Expression and Screening: Express proteins in bacterial systems and screen for solubility, stability, and secondary structure content.

Structural Validation: For promising candidates, determine three-dimensional structures using NMR or X-ray crystallography to verify design principles.

This protocol successfully generated well-ordered four-helix bundle proteins, with the solution structure of S-824 confirming the designed topology [10].

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Semi-Rational Protein Design

| Reagent/Resource | Function in Semi-Rational Design | Specific Examples |

|---|---|---|

| 3DM Database | Analysis of protein superfamily sequences and structures to identify evolutionarily allowed substitutions | Engineering of Pseudomonas fluorescens esterase for improved enantioselectivity [1] |

| HotSpot Wizard | Identification of mutable positions based on sequence and structure analysis | Engineering of haloalkane dehalogenase tunnels for improved activity [1] |

| Rosetta Software Suite | Structure-based energy calculations and library design | SOCoM library optimization for GFP, β-lactamase, and lipase A [13] |

| Degenerate Codons (VAN/NTN) | Implementation of binary patterning for de novo protein design | Construction of four-helix bundle libraries [10] |

| Molecular Dynamics Software (GROMACS) | Simulation of protein dynamics and stability | Validation of α-L-rhamnosidase mutant stability [14] |

| Error-Prone PCR Kits | Introduction of random mutations for initial functional mapping | Generation of M. litoralis α-L-rhamnosidase mutant library [14] |

Case Studies and Applications

AI-Driven De Novo Binder Design

Artificial intelligence and machine learning have dramatically accelerated the design of novel binding proteins, enabling rapid in silico generation of high-affinity binders to diverse and previously intractable targets [15]. This approach represents a paradigm shift from traditional library-based methods to computational design, dramatically reducing binder development time and resource requirements while improving hit rates and designability [15]. Recent successes include the creation of binding proteins that neutralize toxins, modulate immune pathways, and engage disordered targets with high affinity and specificity [15]. Methods like RFdiffusion and ProteinMPNN enable the design of protein structures and sequences with tailored architectures and binding specificities, expanding the scope of what can be designed for therapeutic applications [16].

Engineering of Superstable Proteins Through Maximized Hydrogen Bonding

Computational design combining AI-guided structure prediction with all-atom molecular dynamics simulations has created exceptionally stable proteins through strategic optimization of hydrogen-bond networks [16]. Inspired by natural mechanostable proteins like titin and silk fibroin, researchers designed β-sheet proteins with maximized backbone hydrogen bonds, systematically increasing the number from 4 to 33 [16]. The resulting proteins exhibited remarkable properties:

- Unfolding forces exceeding 1,000 pN (approximately 400% stronger than natural titin immunoglobulin domains)

- Retention of structural integrity after exposure to 150°C

- Formation of thermally stable hydrogels

This molecular-level stability translated directly to macroscopic properties, demonstrating the power of computational design for engineering robust protein systems for extreme environments [16].

Semi-Rational Design of Terpene Synthases

Advances in bioinformatics and availability of detailed enzyme crystal structures have made semi-rational design a powerful strategy for enhancing the catalytic performance of terpene synthases and modifying enzymes [12]. This approach has been successfully applied to key enzymes in the biosynthetic pathways of various terpenes, including mono-, sesqui-, di-, tri-, and tetraterpenes, as well as modifying enzymes such as cytochrome P450s, glycosyltransferases, acetyltransferases, ketolases, and hydroxylases [12]. For example, structure-guided engineering of glycosyltransferase UGT76G1 enhanced production of the sweetener rebaudioside M, while engineering of cytochrome P450 CYP76AH15 improved activity and specificity toward forskolin biosynthesis in yeast [12]. These successes demonstrate how semi-rational design can overcome inherent limitations of native enzymes, such as low catalytic activity and poor stability, to improve production capacity in microbial cell factories [12].

Diagram 2: Strategy selection for library design based on available data and project goals, showing multiple pathways to improved variants.

The shift from large combinatorial libraries to small, functionally-rich libraries represents a fundamental advancement in protein engineering methodology. By leveraging computational modeling, structural insights, and evolutionary information, researchers can now design focused libraries that dramatically improve the efficiency of protein optimization campaigns. These semi-rational approaches have demonstrated success across diverse applications, from engineering stable enzymes for industrial processes to designing novel therapeutic proteins with tailored functions [14] [16] [15]. As computational power increases and AI methods become more sophisticated, the trend toward smaller, smarter library design will continue to accelerate, enabling more ambitious protein engineering projects and expanding the scope of programmable protein functions. The integration of these methodologies represents a new paradigm in protein engineering—one that is increasingly predictive, efficient, and capable of addressing complex challenges in biotechnology and medicine.

In semi-rational protein design, the integration of sequence, structure, and functional information represents a paradigm shift from traditional design methods. This approach leverages computational models to systematically exploit the relationships between a protein's primary sequence, its three-dimensional conformation, and its biological activity. The exponential growth of protein databases and recent breakthroughs in deep learning have dramatically accelerated our ability to predict and manipulate these components, enabling the design of proteins with novel functions and enhanced stability for therapeutic and industrial applications [17].

The core premise of semi-rational design is the interdependence of sequence, structure, and function. A protein's amino acid sequence dictates its folding into a specific three-dimensional structure, which in turn determines its function [18] [17]. Computational modeling serves as the crucial link, allowing researchers to predict the structural and functional outcomes of sequence modifications, thereby guiding the design process with greater precision and efficiency than ever before [18].

Core Data Types and Their Interrelationships

In protein design, three primary data types form the foundation of all computational models.

- Sequence Data: This is the linear string of amino acids that constitutes the primary structure of a protein. It is the most fundamental data type and is directly encoded by genes.

- Structure Data: This refers to the three-dimensional atomic coordinates of a folded protein, defining its tertiary structure. This spatial arrangement is critical for function.

- Functional Information: This encompasses data describing the protein's biological roles, such as its Gene Ontology (GO) terms, Enzyme Commission (EC) numbers, interaction partners, and catalytic activity [19].

The relationship between these components is hierarchical and deeply intertwined. The sequence dictates the possible folds a protein can adopt. The resulting structure creates a specific chemical and geometric environment that enables function, such as binding a ligand or catalyzing a reaction. Advances in deep learning have enabled the creation of multimodal models, such as ProSST, which processes sequence and structure as discrete tokens to uncover the latent relationships between them, thereby enhancing our predictive power for protein properties [19].

Table 1: Key Data Types in Semi-Rational Protein Design

| Data Type | Description | Example Sources | Role in Design |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sequence | Linear amino acid chain | UniProt, GenBank | Provides the primary blueprint for folding and function. |

| Structure | 3D atomic coordinates | Protein Data Bank (PDB), AlphaFold DB | Serves as a template for homology modeling and defines the functional geometry. |

| Function | Biological activity annotations | Gene Ontology (GO), Enzyme Commission (EC) numbers [19] | Provides the target phenotype for design, guiding sequence and structure optimization. |

Quantitative Performance of Integrated Models

Benchmarking studies demonstrate that computational models integrating multiple data types significantly outperform those relying on a single data type. The performance is typically evaluated using metrics such as Template Modeling Score (TM-score) for global structure accuracy, interface accuracy for complexes, and Fmax scores for functional classification tasks.

For protein complex prediction, DeepSCFold, which uses sequence-derived structural complementarity, shows a marked improvement over leading methods. When applied to challenging antibody-antigen complexes, its superiority is even more pronounced, highlighting the value of structural complementarity information in the absence of strong co-evolutionary signals [20].

In the realm of protein property prediction, the SST-ResNet framework, which synergistically uses sequence and structure, achieves state-of-the-art performance on EC number and Gene Ontology prediction tasks, surpassing models that use either sequence or structure alone [19].

Table 2: Benchmarking Performance of Integrated Models

| Model | Core Approach | Test Dataset | Key Metric | Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DeepSCFold [20] | Sequence-derived structure complementarity | CASP15 Multimers | TM-score | 11.6% improvement over AlphaFold-Multimer; 10.3% improvement over AlphaFold3 |

| DeepSCFold [20] | Sequence-derived structure complementarity | SAbDab (Antibody-Antigen) | Interface Prediction Success Rate | 24.7% improvement over AlphaFold-Multimer; 12.4% improvement over AlphaFold3 |

| SST-ResNet [19] | Multimodal sequence-structure integration | Gene Ontology (GO) | Fmax Score | Outperformed previous sequence- or structure-only models |

| SST-ResNet [19] | Multimodal sequence-structure integration | Enzyme Commission (EC) | Fmax Score | Outperformed previous sequence- or structure-only models |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Protein Complex Modeling with DeepSCFold

This protocol details the steps for predicting the structure of a protein complex using the DeepSCFold pipeline, which leverages deep learning to predict interaction probabilities and structural similarity from sequence data [20].

I. Input Preparation and Monomeric MSA Generation

- Input Query: Provide the amino acid sequences of all constituent protein chains in FASTA format.

- Generate Monomeric MSAs: For each individual chain, perform a multiple sequence alignment (MSA) by searching against large sequence databases (e.g., UniRef30, UniRef90, BFD, MGnify) using tools like HHblits or Jackhmmer [20].

II. Construction of Paired MSAs

- Predict Structural Similarity (pSS-score): Use a deep learning model to predict the protein-protein structural similarity between the query sequence and its homologs within the monomeric MSA. Use this pSS-score to refine the ranking and selection of sequences in the monomeric MSA.

- Predict Interaction Probability (pIA-score): For pairs of sequence homologs from different subunit MSAs, use a second deep learning model to predict their interaction probability.

- Concatenate and Filter: Systematically concatenate pairs of sequences from different monomeric MSAs based on their high predicted pIA-scores to construct deep paired multiple sequence alignments (pMSAs). Integrate additional biological information, such as species annotation and known complex data from the PDB, to create biologically relevant paired MSAs [20].

III. Complex Structure Prediction and Model Selection

- Execute AlphaFold-Multimer: Use the constructed series of paired MSAs as input to AlphaFold-Multimer to generate multiple candidate models of the protein complex.

- Select Top Model: Rank the generated models using a complex-specific model quality assessment method (e.g., DeepUMQA-X). Select the top-ranking model (ranked #1) based on the predicted quality.

- Template-Based Refinement: Use the selected top-1 model as an input template for a final iteration of AlphaFold-Multimer to produce the refined, output structure of the complex [20].

Protocol 2: Protein Property Prediction with SST-ResNet

This protocol describes the use of the SST-ResNet framework for predicting protein properties, such as EC numbers and Gene Ontology terms, by integrating sequence and structural information through a multimodal language model [19].

I. Data Input and Tokenization

- Sequence Tokenization: Input the protein's amino acid sequence, treating each amino acid as a discrete sequence token.

- Structure Tokenization:

- Encode Local Structure: For each residue in the protein structure (experimental or predicted), use a pre-trained Geometric Vector Perceptron (GVP) encoder to convert its local structural environment into a dense vector representation.

- Quantize via Clustering: Use a pre-trained k-means clustering model to assign a discrete category label (structure token) to the vector representation of each residue's local structure [19].

II. Multimodal Representation Learning

- Model Processing: Input the paired sequence and structure tokens into the ProSST multimodal language model.

- Feature Extraction: Allow ProSST to process the tokens using its disentangled attention mechanism, which captures the latent relationships between the sequence and structure modalities, and output a combined representation [19].

III. Multi-Scale Integration and Prediction

- Multi-Kernel Convolution: Pass the combined representations through a ResNet-like module that employs convolutional kernels of multiple sizes (e.g., 3x3, 5x5, 7x7) to capture hierarchical features at different spatial scales.

- Feature Aggregation: Aggregate the outputs from the different convolutional kernels.

- Residual Learning: Process the aggregated features through a residual network to facilitate robust fusion and prevent vanishing gradients.

- Classification: Use the final, integrated representation to make synergistic predictions for the target properties, such as EC numbers or GO terms [19].

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the integrated computational workflow for semi-rational protein design, highlighting the synergy between sequence, structure, and functional data.

Protein Design Workflow

Research Reagent Solutions

A successful semi-rational protein design pipeline relies on a suite of computational tools and databases. The table below catalogues essential "research reagents" for the in silico component of this work.

Table 3: Essential Computational Reagents for Semi-Rational Protein Design

| Reagent / Tool Name | Type | Primary Function in Design |

|---|---|---|

| UniProt [20] | Database | Provides comprehensive, annotated protein sequence data. |

| Protein Data Bank (PDB) [20] [17] | Database | Repository of experimentally determined 3D protein structures for template-based modeling and analysis. |

| AlphaFold-Multimer [20] | Deep Learning Model | Predicts the 3D structure of protein complexes from sequence. |

| DeepSCFold [20] | Computational Pipeline | Enhances complex structure prediction by constructing paired MSAs based on predicted structural complementarity. |

| ProSST [19] | Multimodal Language Model | Jointly processes protein sequence and structure as discrete tokens for improved property prediction and representation learning. |

| SST-ResNet [19] | Deep Learning Framework | Integrates multi-scale sequence and structure information for synergistic prediction of protein properties (e.g., EC, GO). |

| ESM [19] | Protein Language Model | Generates evolutionary-aware embeddings from sequence data alone, useful for predicting structure and function. |

| GVP (Geometric Vector Perceptron) [19] | Neural Network Architecture | Encodes local 3D structural information of residues for integration into deep learning models. |

| Rosetta [17] | Software Suite | Provides energy functions and sampling methods for protein structure prediction, design, and refinement. |

Semi-rational protein design represents a paradigm shift in biotechnology, merging the exploratory power of directed evolution with the predictive precision of computational modeling. This approach utilizes knowledge of protein sequence, structure, and function to create smart, focused libraries, enabling researchers to navigate vast sequence spaces with unprecedented efficiency [1] [2]. The methodology marks a transition from discovery-based to hypothesis-driven protein engineering, providing both practical efficiencies and a robust intellectual framework for understanding and optimizing biocatalysts [1]. This document outlines the core advantages and provides detailed protocols for implementing semi-rational design in research and development pipelines.

Quantitative Advantages of Semi-Rational Design

Semi-rational protein engineering delivers measurable improvements in key performance metrics compared to traditional directed evolution. The most significant advantage lies in dramatically reduced experimental burden while maintaining or even improving success rates in obtaining enhanced protein variants.

Table 1: Comparative Efficiency of Semi-Rational vs. Traditional Directed Evolution

| Target Protein | Project Goal | Methodology | Library Size Evaluated | Key Outcome | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pseudomonas fluorescens esterase | Improve enantioselectivity | 3DM analysis & site-saturation mutagenesis | ~500 variants | 200-fold improved activity, 20-fold improved enantioselectivity | [1] |

| Sphingomonas capsulata prolyl endopeptidase | Improve activity & stability | Hot-spot selection & machine learning | 91 variants (over two rounds) | 20% higher activity, 200-fold improved protease resistance | [1] |

| Halogenase (DhaA) | Improve catalytic activity | MD simulations of access tunnels | ~2500 variants | 32-fold improved activity by restricting water access | [1] |

| Gramicidine S synthetase A | Alter substrate specificity | K* algorithm & computational design | <10 variants | 600-fold specificity shift (Phe→Leu) | [1] |

| Phytase (YmPhytase) | Improve activity at neutral pH | AI/ML-powered autonomous platform | <500 variants (over four rounds) | 26-fold higher activity at neutral pH | [21] |

The data demonstrates that semi-rational strategies consistently achieve significant functional improvements while screening orders of magnitude fewer variants than traditional approaches. This efficiency translates directly into reduced resource consumption, shorter development timelines, and the ability to use analytical methods not amenable to high-throughput formats [1] [2].

Foundational Methodologies and Protocols

Sequence-Based Enzyme Redesign

Protocol 1: Evolutionary-Guided Hot-Spot Identification

- Objective: To identify beneficial mutation sites using natural evolutionary information.

Principle: Analyze multiple sequence alignments (MSAs) of protein homologs to determine evolutionary conservation and amino acid variability. Positions with higher natural diversity are often more tolerant to mutation and can be targeted for engineering [1] [6].

Step-by-Step Workflow:

- Sequence Collection: Gather a diverse set of homologous sequences from databases (e.g., GenBank, UniRef) using the target protein as a query.

- Multiple Sequence Alignment: Perform MSA using tools like ClustalOmega, MUSCLE, or MAFFT.

- Conservation Analysis: Calculate per-position conservation scores from the MSA. The 3DM database system can automate this process for entire protein superfamilies, integrating structural data and literature tracking [1].

- Hot-Spot Selection: Select target residues that are:

- Non-conserved in the MSA.

- Located in functionally relevant regions (e.g., near active sites, substrate channels, or domain interfaces).

- Amino Acid Diversity Definition: At selected positions, consider including only amino acids that are "evolutionarily allowed" (i.e., those found in natural homologs) to create higher-quality libraries [1].

Application Note: This protocol was successfully used to engineer an esterase for a 20-fold improvement in enantioselectivity by focusing on four specific amino acid positions preselected via 3DM analysis [1].

Structure-Based Enzyme Redesign

Protocol 2: Structure-Guided Tunnel Engineering

- Objective: To enhance catalytic activity by modifying substrate access or product egress tunnels.

Principle: Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations and structural analysis can identify residues lining access tunnels. Mutations at these positions can modulate tunnel geometry and properties, thereby improving substrate trafficking [1] [6].

Step-by-Step Workflow:

- Structure Preparation: Obtain a high-resolution crystal structure or a reliable homology model of the target enzyme.

- Tunnel Identification: Use software like CAVER (available as a PyMOL plugin) to detect and characterize major tunnels leading from the protein surface to the active site [6].

- Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulations: Perform MD simulations to observe dynamic tunnel behavior and identify key residues involved in gating or defining the tunnel architecture.

- Residue Selection for Mutagenesis: Select tunnel-lining residues that are not part of the catalytic machinery. Tools like HotSpot Wizard can automate this by creating mutability maps from combined sequence and structure data [1].

- Library Construction: Perform site-saturation mutagenesis or incorporate predefined mutations at the selected positions.

Application Note: Applying this protocol to haloalkane dehalogenase (DhaA) identified five key tunnel residues. Subsequent engineering yielded variants with a 32-fold increase in activity by optimizing product release [1].

Computational De Novo Enzyme Design

Protocol 3: Theozyme Implementation into Protein Scaffolds

- Objective: To create entirely new enzymatic activities from scratch.

Principle: This advanced protocol uses quantum mechanical (QM) calculations to design an ideal catalytic site (theozyme) and computational protein design software to match and embed this site into structurally compatible protein scaffolds [1] [6].

Step-by-Step Workflow:

- Theozyme Construction: Use QM/MM simulations to model the transition state of the target reaction and design an optimal arrangement of amino acid side chains (theozyme) that stabilizes it.

- Scaffold Screening: Use algorithms like RosettaMatch to search the Protein Data Bank (PDB) for protein scaffolds that can structurally accommodate the designed theozyme.

- Active Site Design: Use computational design software (e.g., RosettaDesign) to optimize the surrounding active site pocket for precise positioning of the catalytic residues and transition state. The KINematic Closure (KIC) method within Rosetta allows for accurate sampling of protein loop conformations critical for active site formation [22].

- In Silico Screening: Evaluate and rank the designed proteins using scoring functions. Typically, only a small number (10-100) of top-ranking designs are selected for experimental testing [1] [6].

- Experimental Validation: Synthesize the genes for the designed proteins and characterize their activity.

Application Note: This approach has been used to design a stereoselective Diels-Alderase, whose functional performance matches that of catalytic antibodies, demonstrating the power of fully computational enzyme design [1].

Semi-Rational Protein Engineering Workflow

Successful implementation of semi-rational design relies on a suite of specialized computational tools and reagents.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Computational Solutions for Semi-Rational Design

| Item Name / Tool | Category | Primary Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3DM Database | Software / Database | Superfamily analysis, correlated mutation identification | Identifying evolutionarily allowed substitutions for enantioselectivity engineering [1] |

| HotSpot Wizard | Web Server | Identifies functional hot spots from sequence/structure data | Creating a mutability map for targeting key residues [1] |

| Rosetta Software Suite | Software Suite | Protein structure prediction & design (de novo, docking) | Designing novel enzymes (Diels-Alderase) and optimizing active sites [1] [22] |

| CAVER | Software Plugin | Analyzes tunnels and channels in protein structures | Engineering substrate access tunnels in haloalkane dehalogenase [1] [6] |

| ESM-2 (LLM) | AI Model | Predicts amino acid likelihood from sequence context | Generating diverse, high-quality initial mutant libraries autonomously [21] |

| YASARA | Software | Molecular modeling, visualization, MD simulations, docking | Constructing homology models and performing molecular mechanics simulations [6] |

| Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit | Wet-Lab Reagent | Introduces specific mutations into plasmid DNA | Constructing variant libraries based on computational predictions |

| High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase | Wet-Lab Reagent | Accurate amplification for library construction | Ensuring low error rates during PCR-based mutagenesis [21] |

The Intellectual Framework: From Discovery to Hypothesis-Driven Science

Beyond mere efficiency, the most profound impact of semi-rational design is its provision of a robust intellectual framework. It transforms protein engineering from a "black box" discovery process into a hypothesis-driven scientific discipline [1]. Computational models provide testable predictions about structure-function relationships, and experimental results, in turn, feed back to validate and refine these models [23] [6]. This virtuous cycle deepens the fundamental understanding of protein mechanics, creating a powerful feedback loop that accelerates both basic research and applied engineering. The integration of machine learning and large language models, as seen in autonomous engineering platforms, represents the next evolution of this framework, where the cycle of hypothesis, experiment, and learning becomes increasingly automated and powerful [21].

Computational Tools and Practical Applications in Biocatalyst and Therapeutic Design

Semi-rational protein design represents a powerful methodology that merges the depth of computational analysis with the efficiency of experimental screening. By leveraging evolutionary information encapsulated in multiple sequence alignments (MSAs) and phylogenetic analysis, researchers can make informed decisions about which residues to mutate, thereby reducing the immense combinatorial space of possible protein variants. This approach is grounded in the premise that natural evolutionary processes have already sampled a vast landscape of functional sequences, providing key insights into residue importance, functional conservation, and structural constraints. The integration of MSAs and phylogenetic trees enables the identification of co-evolving residues, functional subfamilies, and stability-determining positions that would be difficult to predict from static structural information alone. This Application Note provides detailed protocols and frameworks for implementing sequence-based redesign strategies, with a focus on practical implementation for researchers in computational biology and protein engineering.

Theoretical Foundation: MSAs and Phylogenetic Analysis in Protein Design

The Critical Role of Multiple Sequence Alignments

Multiple sequence alignment serves as the foundational step in sequence-based protein design, enabling direct comparison of homologous sequences to identify conserved and variable regions. The reliability of MSA results directly determines the credibility of subsequent biological conclusions, including those drawn for protein engineering purposes [24]. However, MSA constitutes an NP-hard problem computationally, making it theoretically impossible to guarantee a globally optimal solution. This inherent challenge has led to the development of two primary post-processing strategies for improving initial alignment quality: meta-alignment and realigner methods [24].

Meta-alignment tools such as M-Coffee and TPMA integrate multiple independent MSA results generated from different alignment programs or parameter settings. These methods create consensus alignments that preserve the strongest signals from each input, often revealing alignment patterns not captured by any single tool [24]. Alternatively, realigner methods like ReAligner operate through iterative optimization processes that directly refine existing alignments by locally adjusting regions with potential insertion or mismatch errors without re-running the entire alignment process [24]. For protein engineering applications, high-quality MSAs enable the identification of:

- Conserved catalytic residues critical for function

- Co-evolving networks of residues that may communicate allosterically

- Stability hotspots that vary between functional subfamilies

- Flexible regions that can accommodate mutations

Phylogenetic Analysis for Functional Subfamily Identification

Phylogenetic trees reconstructed from MSAs provide evolutionary context for interpreting sequence variation. By clustering sequences into evolutionary subfamilies, researchers can identify residues that correlate with functional divergence or environmental adaptation. This evolutionary perspective is particularly valuable for distinguishing between positions that are conserved for structural stability versus those conserved for specific functional attributes. The integration of phylogenetic analysis with structural information creates a powerful framework for predicting functional changes resulting from mutations, enabling more informed library design in semi-rational protein engineering campaigns.

Application Notes: Sequence-Based Design Strategies

Consensus Design Approach

Consensus design utilizes the most frequent amino acid at each position across an MSA to create stabilized protein variants. This approach leverages natural selection across diverse organisms, assuming that evolutionary pressure has optimized stability while maintaining function. The underlying principle posits that residues observed more frequently in homologous sequences contribute more favorably to stability than their less common counterparts.

Key considerations for implementation:

- Sequence diversity: The MSA should contain sufficient evolutionary diversity (>100 sequences recommended) to provide meaningful consensus information

- Subfamily weighting: Avoid averaging across distinct functional classes; instead, focus on subfamilies relevant to the desired protein function

- Gap treatment: Positions with high gap frequency often indicate structural flexibility or functionally unimportant regions

Statistical Coupling Analysis for Co-Evolution Networks

Statistical Coupling Analysis (SCA) and similar methods identify networks of co-evolving residues that often comprise allosteric pathways or functional sites. These approaches analyze correlations in amino acid usage patterns across an MSA to reveal residues that evolutionarily "communicate" with each other.

Application in semi-rational design:

- Allosteric regulation: Designing mutations in co-evolving networks to modulate allostery

- Functional enhancement: Targeting positions with high co-evolution scores for mutagenesis to alter function

- Stability-function tradeoffs: Identifying positions where mutations may affect both stability and function through their network connections

Ancestral Sequence Reconstruction

Ancestral sequence reconstruction uses phylogenetic models to infer ancestral proteins at different evolutionary nodes, often resulting in variants with enhanced stability and promiscuity. A case study on glycosyltransferase engineering utilized ancestral reconstruction to create efficient catalysts for synthesizing rare ginsenoside Rh1 [12].

Implementation workflow:

- Build a robust phylogeny from a diverse MSA

- Select reconstruction nodes based on evolutionary significance

- Infer ancestral sequences using probabilistic models (e.g., maximum likelihood)

- Screen ancestral variants for desired properties

Table 1: Semi-Rational Design Strategies and Their Applications in Protein Engineering

| Design Strategy | Key Principle | Typical Application | Data Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|

| Consensus Design | Select most frequent amino acids in MSA | Thermal stability enhancement | MSA of >100 homologs |

| Statistical Coupling Analysis | Identify networks of co-evolving residues | Allosteric control, functional enhancement | Large MSA (>200 sequences) of diverse homologs |

| Ancestral Reconstruction | Resurrect inferred ancestral sequences | Thermostability, substrate promiscuity | Phylogeny with diverse sequences spanning desired nodes |

| Evolutionary Mining | Extract subfamily-specific patterns | Functional specialization, substrate specificity | MSA containing distinct functional subfamilies |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: MSA Construction and Curation for Protein Engineering

Objective: Generate a high-quality MSA suitable for identifying mutation targets in semi-rational design.

Materials and Reagents:

- Target protein sequence in FASTA format

- Multiple sequence databases (e.g., UniProt, NCBI NR)

- MSA software (MAFFT, MUSCLE, or Clustal Omega)

- MSA post-processing tools (M-Coffee, T-Coffee)

- Computing resources (workstation or cluster)

Procedure:

- Sequence Collection

- Perform BLASTP search against UniProt database with default parameters

- Set E-value threshold to 0.001 to balance diversity and homology

- Collect up to 1000 homologous sequences, avoiding fragments (<80% length of target)

- Save sequences in FASTA format

Alignment Generation

- Execute MAFFT with G-INS-I algorithm for highest accuracy:

- For larger datasets (>500 sequences), use FFT-NS-2 strategy for efficiency

- Alignments can be validated with NorMD scores or similar quality metrics [24]

Post-processing and Refinement

- Apply meta-alignment using M-Coffee to integrate multiple methods:

- Remove poorly aligned regions using trimAl:

- Visually inspect alignment using Jalview or similar tools

Conservation Analysis

- Calculate position-specific conservation scores (e.g., Shannon entropy)

- Identify fully conserved residues (potential functional/structural essentials)

- Map variable regions (potential mutagenesis targets)

Troubleshooting:

- If alignment contains too many gaps, adjust sequence similarity thresholds

- If conservation patterns are unclear, expand or refine sequence dataset

- For difficult-to-align regions, consider structural constraints if available

Protocol 2: Phylogenetic Analysis for Functional Subfamily Identification

Objective: Construct phylogenetic trees to identify evolutionary subfamilies and correlate their sequence features with functional attributes.

Materials and Reagents:

- Curated MSA from Protocol 1

- Phylogenetic software (IQ-TREE, RAxML, or PhyML)

- Tree visualization tools (FigTree, iTOL)

Procedure:

- Model Selection

- Use ModelFinder in IQ-TREE to identify best-fitting substitution model:

- Note model with lowest Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC)

Tree Construction

- Build maximum likelihood tree with best model:

- Perform 1000 ultrafast bootstrap replicates for branch support

Subfamily Identification

- Visually inspect tree for distinct clades with high support (>80% bootstrap)

- Extract sequences from each subfamily

- Generate subfamily-specific sequence logos

Correlation with Function

- If functional data available, map to tree tips

- Identify subfamily-specific residues correlated with functional differences

- Select candidate positions for site-directed mutagenesis

Analysis Notes:

- Subfamilies with long branch lengths may indicate functional divergence

- Convergent evolution across clades suggests important adaptive mutations

- Root tree using appropriate outgroup for directional evolutionary analysis

Protocol 3: Integration with Structure-Guided Design

Objective: Combine evolutionary information with structural data to select mutation sites and amino acid substitutions.

Materials and Reagents:

- Conservation analysis from Protocol 1

- Phylogenetic subfamilies from Protocol 2

- Protein structure (experimental or predicted)

- Molecular visualization software (PyMOL, ChimeraX)

Procedure:

- Structure Conservation Mapping

- Map conservation scores onto protein structure

- Identify surface patches of high conservation (potential functional sites)

- Note conserved residues in active site or protein core

Subfamily-Specific Structural Analysis

- For each subfamily, model representative sequences using AlphaFold2

- Compare structures to identify conformational differences

- Correlase subfamily-specific residues with structural variations

Mutation Site Selection

- Prioritize sites with intermediate conservation (neither fully conserved nor highly variable)

- Focus on positions that differ between functional subfamilies

- Avoid buried core residues unless specifically targeting stability

Amino Acid Substitution Design

- For variable positions, consider subfamily-specific amino acid preferences

- Incorporate biochemical similarity in substitution choices

- Use computational tools (Rosetta, FoldX) to predict stability effects

Design Output:

- List of prioritized mutation sites with suggested substitutions

- Structural models of designed variants

- Preliminary stability and function predictions

Case Studies in Semi-Rational Engineering

Engineering Alkali-Tolerant α-L-Rhamnosidase

A recent study demonstrated the power of combining random mutagenesis with semi-rational design to enhance the alkali tolerance of Metabacillus litoralis C44 α-L-rhamnosidase [14]. Researchers first performed error-prone PCR to generate a mutant library, identifying both improved and inactive variants. Analysis of inactivation mutants revealed critical positions where reverse mutations actually enhanced enzymatic activity compared to wild-type. Semi-rational design strategies included:

- Surface charge modification to improve alkali tolerance

- Substrate pocket saturation to enhance substrate binding

- Reduction of unfolding free energy to improve stability

The resulting mutant R-28 (K89R-K70R-E475D) exhibited significantly improved alkali tolerance, stability, and enzymatic activity. Molecular dynamics simulations confirmed reduced binding free energies for both rutin substrate and isoquercitrin product, explaining the enhanced performance at high rutin concentrations (up to 300 g/L) [14].

Enhancing Thermostability of Terpene Synthases

Semi-rational design has successfully improved the catalytic performance of terpene synthases and their modifying enzymes [12]. For example:

- Glycosyltransferase engineering from Panax ginseng improved thermostability and catalytic activity for Rebaudioside D synthesis through structure-guided mutations informed by sequence analysis [12]

- Ancestral sequence reconstruction of glycosyltransferase enabled efficient production of rare ginsenoside Rh1 [12]

- Structure-guided engineering of glycosyltransferase UGT76G1 enhanced production of Rebaudioside M through mutations informed by sequence-structure analysis [12]

These cases demonstrate how evolutionary information guides effective mutation choices that would be difficult to identify through purely structure-based or random approaches.

Table 2: Representative Successful Applications of Sequence-Based Redesign

| Protein Target | Engineering Strategy | Key Mutations | Experimental Outcome | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| α-L-Rhamnosidase (MlRha4) | Surface charge optimization, unfolding energy reduction | K89R, K70R, E475D | Improved alkali tolerance, 300 g/L rutin conversion | [14] |

| Glycosyltransferase (UGTSL2) | Semi-rational design based on subfamily analysis | Asn358Phe | Efficient Reb D production from stevioside | [12] |

| Glycosyltransferase (Panax ginseng) | Structure-guided consensus design | Multiple stability mutations | Improved thermostability and catalytic activity | [12] |

| Glycosyltransferase (UGT76G1) | Structure-guided engineering | Not specified | Enhanced Rebaudioside M production | [12] |

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Sequence-Based Redesign

| Reagent/Resource | Function/Application | Example Products/Tools | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sequence Databases | Source of homologous sequences for MSA construction | UniProt, NCBI NR, Pfam, InterPro | |

| Alignment Software | Generate multiple sequence alignments | MAFFT, MUSCLE, Clustal Omega, T-Coffee | |

| Phylogenetic Tools | Construct evolutionary trees from alignments | IQ-TREE, RAxML, PhyML, MrBayes | |

| Post-processing Algorithms | Refine and improve initial alignments | M-Coffee, TPMA, RASCAL, trimal | |

| Structure Prediction | Generate 3D models for structure-function analysis | AlphaFold2, RoseTTAFold, Rosetta, MODELLER | |

| Stability Prediction | Estimate thermodynamic stability changes from mutations | FoldX, Rosetta ddG, I-Mutant, CUPSAT | |

| Data Repository | Store and share protein engineering data | ProtaBank, PDB, UniProt | [25] |

Workflow Visualization

Diagram 1: Sequence-Based Redesign Workflow

Diagram 2: Semi-Rational Design Strategy Framework

Structure-based protein redesign represents a cornerstone of modern computational biology, enabling the rational engineering of proteins for enhanced stability, novel catalytic activity, and specific molecular recognition. This protocol details an integrated computational pipeline combining evolutionary analysis via SCHEMA, energy-based design using Rosetta, and binding validation through molecular docking. Framed within a broader thesis on semi-rational protein design, this approach systematically navigates the sequence-structure-function landscape to achieve predictable protein engineering outcomes. The methodology is particularly valuable for drug development professionals seeking to create therapeutic proteins with optimized properties, where controlling binding interactions and stability is paramount. By leveraging the complementary strengths of these tools, researchers can efficiently explore vast sequence spaces that would be prohibitively expensive to screen experimentally.

Background and Significance

The foundational principle of structure-based redesign lies in the relationship between protein sequence, three-dimensional structure, and biological function. Traditional rational design approaches often focus on limited mutations based solely on structural analysis, while purely random methods require high-throughput screening. Semi-rational strategies bridge this gap by using computational models to intelligently constrain sequence space to regions most likely to yield functional variants.

SCHEMA employs protein block modeling to facilitate the recombination of protein fragments while minimizing structural disruptions, effectively exploring functional sequence diversity [26]. The Rosetta software suite provides physics-based and knowledge-based energy functions to evaluate and predict the stability of these designed sequences [27] [28]. Finally, molecular docking validates that designed proteins maintain or achieve desired binding specificities, with advanced protocols like ReplicaDock addressing the challenge of conformational flexibility upon binding [29].

The integration of these methods has become increasingly powerful with the advent of deep learning architectures. Tools like AlphaFold now provide accurate structural templates, while protein language models (ESM, AntiBERTy) offer insights into sequence plausibility and developability [27] [30]. This pipeline represents the current state-of-the-art in computational protein engineering, combining evolutionary information with biophysical principles.

Computational Requirements and Reagents

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 1: Essential computational tools and their functions in structure-based redesign

| Tool Name | Type | Primary Function | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| SCHEMA | Algorithm/Software | Protein block modeling & recombination | Creating chimeric proteins, minimizing structural disruption [26] |

| Rosetta | Software Suite | Energy-based structure prediction & design | Protein-protein docking, side-chain optimization, stability calculations [27] [28] |