Self-Supervised Learning for Protein Data: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomedical Research and Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of self-supervised learning (SSL) methodologies applied to protein data, a transformative approach addressing the critical challenge of limited labeled data in computational biology.

Self-Supervised Learning for Protein Data: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomedical Research and Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of self-supervised learning (SSL) methodologies applied to protein data, a transformative approach addressing the critical challenge of limited labeled data in computational biology. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it covers foundational SSL concepts specific to protein sequences and structures, details cutting-edge methodological architectures like protein language models and structure-aware GNNs, and offers practical strategies for troubleshooting and optimizing model performance. Further, it synthesizes validation frameworks and performance benchmarks across key downstream tasks such as structure prediction, function annotation, and stability analysis, serving as an essential resource for leveraging SSL to accelerate biomedical discovery and therapeutic development.

The Rise of Self-Supervised Learning in Protein Science: Overcoming Data Scarcity

The central challenge in modern computational biology lies in bridging the protein sequence-structure gap—the fundamental disconnect between the linear amino acid sequences that define a protein's primary structure and the complex, three-dimensional folds that determine its biological function. While advances in sequencing technologies have generated billions of protein sequences, experimentally determining protein structures through methods like X-ray crystallography or cryo-electron microscopy remains expensive, time-consuming, and technically challenging. This has resulted in a massive disparity between the number of known protein sequences and those with experimentally resolved structures, creating a critical bottleneck in our ability to understand protein function and engineer novel therapeutics.

Self-supervised learning (SSL) has emerged as a transformative paradigm for addressing this challenge by leveraging unlabeled data to learn meaningful protein representations. Traditional supervised learning approaches for protein structure prediction are severely constrained by the limited availability of labeled structural data. SSL methods circumvent this limitation by pretraining models on vast corpora of unlabeled protein sequences and structures, allowing them to learn the fundamental principles of protein folding and function without requiring explicit structural annotations for every sequence. These methods create models that capture evolutionary patterns, physical constraints, and structural preferences encoded in protein sequences, enabling accurate prediction of structural features and functional properties [1].

The significance of bridging this gap extends across multiple biological domains. In drug discovery, understanding protein structure is crucial for identifying drug targets, predicting drug-drug interactions, and designing therapeutic molecules. For example, computational models that integrate protein sequence and structure information have demonstrated superior performance in predicting drug-drug interactions (DDIs), achieving precision rates of 91%–98% and recall of 90%–96% in recent evaluations [2]. In functional annotation, protein structure provides critical insights into molecular mechanisms, catalytic sites, and binding interfaces that sequence information alone cannot fully reveal.

Computational Frameworks for Leveraging Unlabeled Data

Self-Supervised Learning Strategies for Protein Data

Self-supervised learning frameworks for proteins can be broadly categorized into sequence-based and structure-aware approaches. Sequence-based methods, inspired by natural language processing, treat proteins as sequences of amino acids and employ transformer architectures or recurrent neural networks trained on masked language modeling objectives. These models learn to predict masked residues based on their contextual surroundings, capturing evolutionary patterns and co-variance signals that hint at structural constraints. While powerful, these methods primarily operate on sequence information alone and may not explicitly capture complex structural determinants [1].

Structure-aware SSL methods represent a significant advancement by directly incorporating three-dimensional structural information during pretraining. The STrucure-awarE Protein Self-supervised learning (STEPS) framework exemplifies this approach by using graph neural networks (GNNs) to model protein structures as graphs, where nodes represent residues and edges capture spatial relationships [1]. This framework employs two novel self-supervised tasks: pairwise residue distance prediction and dihedral angle prediction, which explicitly incorporate finer structural details into the learned representations. By reconstructing these structural elements from masked inputs, the model develops a sophisticated understanding of protein folding principles.

Recent geometric SSL approaches further extend this paradigm by focusing on the spatial organization of proteins. One method pretrains 3D GNNs by predicting distances between local geometric centroids of protein subgraphs and the global geometric centroid of the entire protein [3]. This approach enables the model to learn hierarchical geometric properties of protein structures without requiring explicit structural annotations, demonstrating that meaningful representations can be learned through carefully designed pretext tasks that capture essential structural constraints.

Meta-Learning for Data-Scarce Protein Problems

Meta-learning, or "learning to learn," provides another powerful framework for addressing data scarcity in protein research. This approach is particularly valuable for protein function prediction, where many functional categories have only a few labeled examples. Meta-learning algorithms acquire prior knowledge across diverse protein tasks, enabling rapid adaptation to new tasks with limited labeled data [4]. Optimization-based methods like Model-Agnostic Meta-Learning (MAML) and metric-based approaches such as prototypical networks have shown promising results in few-shot protein function prediction and rare cell type identification [4].

These methods are especially relevant for bridging the sequence-structure gap because they can leverage knowledge from well-characterized protein families to make predictions about poorly annotated ones. By learning transferable representations across diverse protein classes, meta-learning models can infer structural and functional properties for proteins with limited experimental data, effectively amplifying the value of existing structural annotations.

Experimental Protocols and Performance Benchmarks

Quantitative Performance of Protein Representation Learning Methods

Table 1: Performance benchmarks of self-supervised learning methods on protein structure and function prediction tasks

| Method | SSL Approach | Data Modalities | Membrane/Non-membrane Classification (F1) | Location Classification (Accuracy) | Enzyme Reaction Prediction (Accuracy) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| STEPS [1] | Structure-aware GNN | Sequence + Structure | 0.89 | 0.78 | 0.72 |

| Geometric Pretraining [3] | Geometric SSL | 3D Structure | 0.85 | 0.81 | 0.69 |

| Sequence-only SSL [1] | Masked Language Modeling | Sequence Only | 0.82 | 0.72 | 0.65 |

| Supervised Baseline [1] | Fully Supervised | Sequence + Structure | 0.80 | 0.70 | 0.62 |

Table 2: Protein structure-based DDI prediction performance of PS3N framework [2]

| Dataset | Precision (%) | Recall (%) | F1 Score (%) | AUC (%) | Accuracy (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dataset 1 | 91-94 | 90-93 | 86-90 | 88-92 | 86-90 |

| Dataset 2 | 95-98 | 94-96 | 92-95 | 96-99 | 92-95 |

Detailed Methodologies for Key Experiments

Protocol 1: Structure-Aware Self-Supervised Pretraining with STEPS Framework

The STEPS framework employs a dual-task self-supervised approach to capture protein structural information [1]:

Protein Graph Construction: Represent protein structure as a graph ( G(V,E) ) where ( V ) is the set of residues and ( E ) contains edges between residues with spatial distance below a threshold (typically 6-10Å). Node features include dihedral angles (( \phi ), ( \psi )) and pretrained residue embeddings from protein language models.

Graph Neural Network Architecture: Implement a GNN model using the framework from Xu et al. (2018) with the following propagation rules:

- ( ai^{(k)} = \text{AGGREGATE}^{(k)}({e{iv}h_v^{(k-1)}|\forall v\in \mathcal{N}(i)}) )

- ( hi^{(k)} = \text{COMBINE}^{(k)}(hi^{(k-1)}, ai^{(k)}) ) where ( e{iv} ) represents edge features (inverse square of pairwise residue distance), and ( \mathcal{N}(i) ) denotes neighbors of node i.

Self-Supervised Pretraining Tasks:

- Distance Prediction: Randomly mask portions of the protein graph and train the model to reconstruct pairwise residue distances using mean squared error loss.

- Angle Prediction: Predict dihedral angles (( \phi ), ( \psi )) for masked residues using circular loss functions that account for angle periodicity.

Knowledge Integration: Incorporate sequential information from protein language models through a pseudo bi-level optimization scheme that maximizes mutual information between sequential and structural representations while keeping the protein LM parameters fixed.

Protocol 2: Geometric Self-Supervised Pretraining on 3D Protein Structures

This approach focuses on capturing hierarchical geometric properties of proteins [3]:

Subgraph Generation: Decompose protein structures into meaningful subgraphs based on spatial proximity and structural motifs.

Centroid Distance Prediction: For each subgraph, compute its geometric centroid. The pretraining objective is to predict distances between:

- Local subgraph centroids

- Global protein structure centroid

- Between local centroids of different subgraphs

Graph Neural Network Architecture: Employ 3D GNNs that operate directly on atomic coordinates and spatial relationships, using message-passing mechanisms that respect geometric constraints.

Multi-Scale Learning: Capture protein structure at multiple scales—from local residue arrangements to global domain organization—through hierarchical graph representations.

Protocol 3: Protein Sequence-Structure Similarity for Drug-Drug Interaction Prediction (PS3N)

The PS3N framework leverages protein structural information to predict novel drug-drug interactions [2]:

Data Collection: Compile diverse drug information including:

- Drug-drug interactions from DrugBank

- Drug attributes: active ingredients, protein targets

- Protein sequences and 3D structures for drug targets

Similarity Computation: Calculate multiple similarity metrics between drugs based on:

- Protein sequence similarity using alignment scores

- Protein structure similarity using spatial feature comparisons

- Chemical structure similarity

- Side effect profiles

Neural Network Architecture: Implement a similarity-based neural network that integrates multiple similarity measures through dedicated encoding branches, followed by cross-similarity attention mechanisms and fusion layers.

Training Procedure: Optimize model parameters using multi-task learning objectives that jointly predict DDIs and reconstruct similarity relationships, with regularization terms to prevent overfitting on sparse interaction data.

Table 3: Essential research reagents and computational tools for protein SSL research

| Resource | Type | Function | Access |

|---|---|---|---|

| AlphaFold2 Database [1] | Data Resource | Provides predicted protein structures for numerous sequences | https://alphafold.ebi.ac.uk/ |

| Protein Data Bank (PDB) [1] | Data Resource | Repository of experimentally determined protein structures | https://www.rcsb.org/ |

| STEPS Codebase [1] | Software | Implementation of structure-aware protein self-supervised learning | https://github.com/GGchen1997/STEPS_Bioinformatics |

| Protein Language Models | Software | Pretrained sequence-based models for transfer learning | Various repositories |

| Graph Neural Network Libraries | Software | Frameworks for implementing structure-based learning models | PyTorch Geometric, DGL |

| DrugBank [2] | Data Resource | Database of drug-drug interactions and drug target information | https://go.drugbank.com/ |

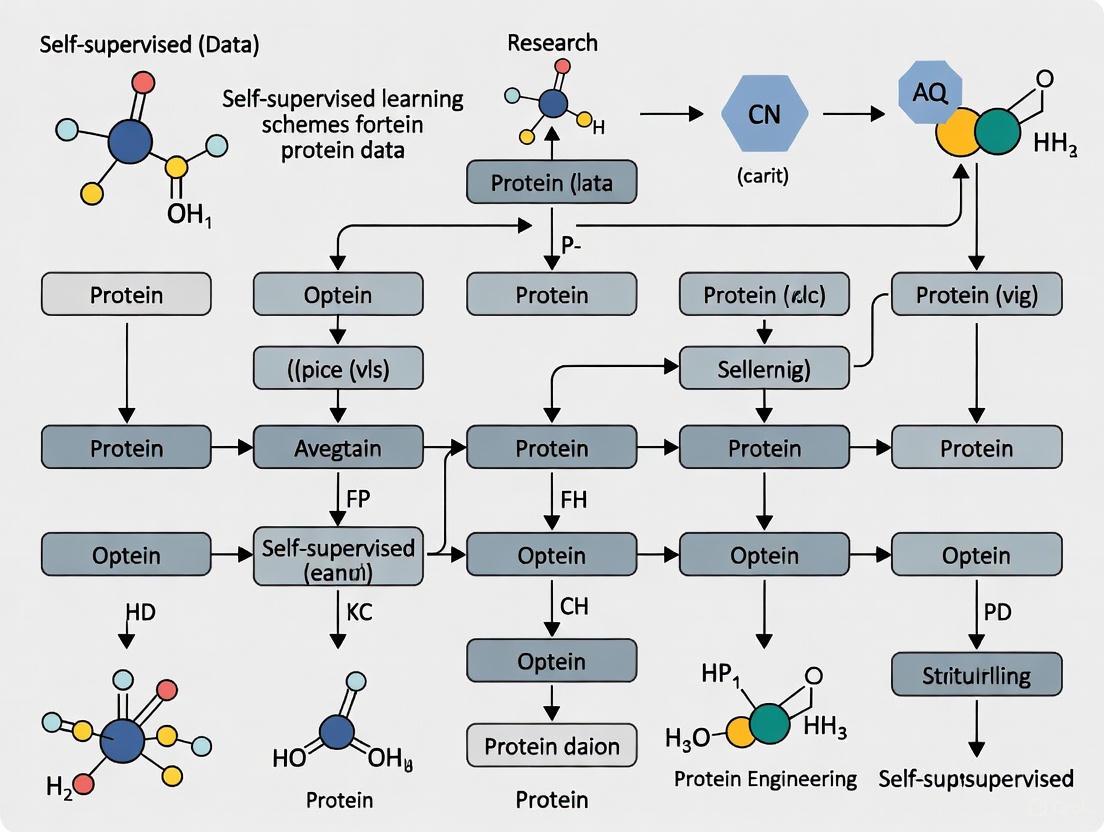

Technical Implementation and Workflow Visualization

Structure-Aware Protein Self-Supervised Learning Workflow

Protein Graph Neural Network Architecture

Geometric Self-Supervised Pretraining Approach

Self-supervised learning represents a paradigm shift in computational biology, offering powerful frameworks for bridging the protein sequence-structure gap by leveraging unlabeled data. The integration of structural information through graph neural networks and geometric learning approaches has demonstrated significant improvements in protein representation learning, enabling more accurate function prediction, drug interaction forecasting, and structural annotation. As these methods continue to evolve, we anticipate further advancements in multi-modal learning that combine sequence, structure, and functional data, as well as more sophisticated few-shot learning approaches that can generalize from limited labeled examples. The ongoing development of these computational techniques promises to accelerate drug discovery, protein engineering, and our fundamental understanding of biological systems by finally bridging the divide between sequence information and structural reality.

Self-supervised learning (SSL) has emerged as a transformative framework in computational biology, enabling researchers to extract meaningful patterns from vast amounts of unlabeled protein data. In protein informatics, where obtaining labeled experimental data remains expensive and time-consuming, SSL provides a powerful alternative by creating learning objectives directly from the data itself without human annotation. This approach has demonstrated remarkable success across diverse applications including molecular property prediction, drug-target binding affinity estimation, protein fitness prediction, and protein structure determination. The fundamental advantage of SSL lies in its ability to leverage the enormous quantities of available unlabeled protein sequences and structures – from public databases like UniProt and the Protein Data Bank – to learn rich, generalizable representations that capture essential biological principles. These pre-trained models can then be fine-tuned on specific downstream tasks with limited labeled data, significantly accelerating research in drug discovery and protein engineering.

This technical guide examines the core principles of self-supervised learning as applied to protein data, focusing on the pretext tasks that enable models to learn powerful representations, the architectural innovations that facilitate this learning, and the practical methodologies for applying these techniques in real-world research scenarios. By understanding these foundational concepts, researchers can better leverage SSL to advance their work in protein design, function prediction, and therapeutic development.

Core SSL Principles and Pretext Tasks

Foundational SSL Concepts

Self-supervised learning operates on a simple yet powerful premise: create supervisory signals from the intrinsic structure of unlabeled data. For protein sequences and structures, this involves designing pretext tasks that require the model to learn meaningful biological patterns without external labels. The SSL pipeline typically involves two phases: (1) pre-training, where models learn general protein representations by solving pretext tasks on large unlabeled datasets, and (2) fine-tuning, where these pre-trained models are adapted to specific downstream tasks using smaller labeled datasets.

The mathematical foundation of SSL lies in learning an encoder function fθ that maps input data X to meaningful representations Z = fθ(X), where the parameters θ are learned by optimizing objectives designed to capture structural, evolutionary, or physicochemical properties of proteins. Unlike supervised learning which maximizes P(Y|X) for labels Y, SSL objectives are designed to capture P(X) or internal relationships within X itself [5] [6].

Key Pretext Tasks for Protein Data

SSL methods for proteins employ diverse pretext tasks tailored to biological sequences and structures. The table below summarizes the most influential categories and their implementations:

Table 1: Key Pretext Tasks for Protein SSL

| Pretext Task Category | Core Mechanism | Biological Insight Captured | Example Methods |

|---|---|---|---|

| Masked Language Modeling | Randomly masks portions of input sequence/structure and predicts masked elements from context | Context-dependent residue properties, evolutionary constraints | ESM-1v, ProteinBERT [7] [6] |

| Contrastive Learning | Maximizes agreement between differently augmented views of same protein while distinguishing from different proteins | Structural invariants, functional similarities | MolCLR, ProtCLR [8] |

| Autoregressive Modeling | Predicts next element in sequence given previous elements | Sequential dependencies, local structural patterns | GPT-based protein models [9] |

| Multi-task Self-supervision | Combines multiple pretext tasks simultaneously | Comprehensive representation capturing diverse protein properties | MTSSMol [8] |

| Evolutionary Modeling | Leverages homologous sequences through multiple sequence alignments | Evolutionary conservation, co-evolutionary patterns | MSA Transformer [6] |

These pretext tasks can be applied to different protein representations including amino acid sequences, 3D structures, and evolutionary information. For example, masked language modeling has been successfully adapted from natural language processing to protein sequences by treating amino acids as tokens and predicting randomly masked residues based on their context within linear sequences [6]. For structural data, graph-based SSL methods mask node or edge features in molecular graphs and attempt to reconstruct them based on the overall structure [7].

SSL Architectures for Protein Representation

Transformer-based Architectures

Transformer architectures have revolutionized protein SSL through their self-attention mechanism, which enables modeling of long-range dependencies in protein sequences – a critical capability given that distal residues in sequence space often interact closely in 3D space to determine protein function. The core self-attention operation computes weighted sums of value vectors based on compatibility between query and key vectors:

[ \text{Attention}(Q, K, V) = \text{softmax}\left(\frac{QK^T}{\sqrt{d_k}}\right)V ]

Where Q, K, and V are query, key, and value matrices derived from input sequence embeddings, and d_k is the dimension of key vectors [9]. This mechanism allows each position in the protein sequence to attend to all other positions, capturing complex residue-residue interactions that underlie protein folding and function.

Transformer models for proteins typically undergo large-scale pre-training on millions of protein sequences from databases like UniRef, learning generalizable representations that encode structural and functional information. For example, ESM-1v was trained using masked language modeling on 150 million sequences from the UniRef90 database, achieving exceptional zero-shot fitness prediction on 41 deep mutation scanning datasets with an average Spearman's rho of 0.509 [7]. These pre-trained models can then be fine-tuned on specific downstream tasks with limited labeled data, demonstrating remarkable transfer learning capabilities.

Graph Neural Networks for Structural Data

Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) provide a natural architectural framework for representing and learning from protein structures. In GNN-based SSL, proteins are represented as graphs where nodes correspond to amino acids (or atoms) and edges represent spatial proximity or chemical bonds. The message-passing mechanism in GNNs enables information propagation through the graph structure, capturing local and global structural patterns essential for understanding protein function.

For a protein graph G = (V, E) with nodes V and edges E, the message passing at layer k can be described as:

[ \begin{align} av^{(k)} &= \text{AGGREGATE}^{(k)}({hu^{(k-1)} : u \in N(v)}) \ hv^{(k)} &= \text{COMBINE}^{(k)}(hv^{(k-1)}, a_v^{(k)}) \end{align} ]

Where (h_v^{(k)}) is the feature of node v at layer k, N(v) denotes neighbors of v, and AGGREGATE and COMBINE are differentiable functions [8]. This formulation allows GNNs to capture complex atomic interactions that determine protein stability and function.

SSL pretext tasks for GNNs include masked attribute prediction (predicting masked node or edge features), contrastive learning between structural augmentations, and self-prediction tasks. For example, Pythia employs a GNN-based SSL approach where the model learns to predict amino acid types at specific positions within protein structures, enabling zero-shot prediction of free energy changes (ΔΔG) resulting from mutations [7].

Multi-Modal and Hybrid Approaches

The most powerful SSL approaches for proteins often integrate multiple data modalities and architectural paradigms. Multi-modal SSL combines sequence, structure, and evolutionary information to learn more comprehensive representations that capture complementary aspects of protein biology. Hybrid architectures might combine Transformers for sequence processing with GNNs for structural reasoning, leveraging the strengths of each architectural type.

For example, MTSSMol employs a multi-task SSL strategy that integrates both chemical knowledge and structural information through multiple pretext tasks including multi-granularity clustering and graph masking [8]. This approach demonstrates that combining diverse SSL objectives can lead to more robust and generalizable representations than single-task pre-training.

Table 2: SSL Architecture Comparison for Protein Data

| Architecture | Primary Data Type | Key Strengths | Representative Models |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transformer | Amino acid sequences | Captures long-range dependencies, scalable to billions of parameters | ESM-1v, ProtBERT, AlphaFold [9] [6] |

| Graph Neural Networks | 3D protein structures | Models spatial relationships, inherently captures local interactions | Pythia, GNN-based SSL [7] [8] |

| Recurrent Networks | Linear sequences | Effective for sequential dependencies, computational efficiency | Self-GenomeNet [10] |

| Hybrid Models | Multiple modalities | Combines complementary information sources, more biologically complete | MTSSMol, Multimodal fusion networks [8] [6] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

SSL Pre-training Implementation

Implementing effective SSL for protein data requires careful attention to data preparation, model architecture selection, and training procedures. The following protocol outlines a standardized approach for protein SSL pre-training:

Data Preparation: Curate a large, diverse set of protein sequences or structures from databases such as UniProt, Protein Data Bank, or AlphaFold Database. For sequence-based methods, this may involve 10-100 million sequences, while structure-based methods typically use smaller datasets of high-resolution structures. Preprocessing may include filtering by sequence quality, removing redundancies, and standardizing representations.

Pretext Task Design: Select appropriate pretext tasks based on the data type and target applications. For sequence data, masked language modeling typically masks 10-20% of residues. For structural data, contrastive learning between spatially augmented views or masked attribute prediction works effectively.

Model Configuration: Choose an architecture suited to the data type – Transformers for sequences, GNNs for structures, or hybrid models for multi-modal data. Set hyperparameters including model dimension (512-4098), number of layers (6-48), attention heads (8-64), and batch size (256-4096 examples) based on available computational resources.

Training Procedure: Utilize the AdamW or LAMB optimizer with learning rate warming followed by cosine decay. Training typically requires significant computational resources – from days on 8 GPUs for moderate models to weeks on TPU pods for large-scale models like ESM-2 and AlphaFold. Regularly validate representation quality on downstream tasks to monitor training progress [7] [8] [6].

The following diagram illustrates the complete SSL pre-training workflow for protein data:

Downstream Task Fine-tuning

After SSL pre-training, models are adapted to specific downstream tasks through fine-tuning:

Task-Specific Data Preparation: Gather labeled datasets for the target application (e.g., protein function annotation, stability prediction, drug-target interaction). Split data into training, validation, and test sets, ensuring no overlap between pre-training and fine-tuning data.

Model Adaptation: Replace the pre-training head with task-specific output layers. For classification tasks, this typically involves a linear layer followed by softmax; for regression tasks, a linear output layer.

Fine-tuning Procedure: Initialize with pre-trained weights and train on the labeled dataset using lower learning rates (typically 1-10% of pre-training rate) to avoid catastrophic forgetting. Employ gradual unfreezing strategies – starting with the output layer and progressively unfreezing earlier layers – to balance adaptation with retention of general features. Monitor performance on validation sets to determine stopping points and avoid overfitting [8] [10].

Experimental Validation and Performance

Benchmark Results

SSL methods for proteins have demonstrated state-of-the-art performance across diverse benchmarks. The table below summarizes key quantitative results from recent SSL protein models:

Table 3: Performance Benchmarks of SSL Protein Models

| Model | SSL Approach | Benchmark Task | Performance | Comparative Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pythia [7] | Self-supervised GNN | ΔΔG prediction (zero-shot) | State-of-the-art accuracy, 10^5x speedup vs force fields | Outperforms force field-based approaches while competitive with supervised models |

| ESM-1v [7] | Masked language modeling | Mutation effect prediction | Spearman's rho = 0.509 (avg across 41 DMS datasets) | Zero-shot performance comparable to supervised methods |

| MTSSMol [8] | Multi-task SSL | Molecular property prediction (27 datasets) | Exceptional performance across domains | Effective identification of FGFR1 inhibitors validated by molecular dynamics |

| Self-GenomeNet [10] | Contrastive predictive coding | Genomic task classification | Outperforms supervised training with 10x fewer labeled data | Generalizes well to new datasets and tasks |

| MERGE + SVM [11] | Semi-supervised with DCA encoding | Protein fitness prediction | Superior performance with limited labeled data | Effectively leverages evolutionary information from homologs |

These results demonstrate that SSL approaches can match or exceed supervised methods while requiring minimal labeled data for downstream tasks. The performance gains are particularly pronounced in data-scarce scenarios common in protein engineering and drug discovery.

Case Study: Pythia for Protein Stability Prediction

Pythia provides an instructive case study of specialized SSL for protein engineering. The model employs a graph neural network architecture that represents protein local structures as k-nearest neighbor graphs, with nodes corresponding to amino acids and edges connecting spatially proximate residues. Node features include amino acid type, backbone dihedral angles, and relative positional encoding, while edge features incorporate distances between backbone atoms.

Pythia's SSL pretext task involves predicting the natural amino acid type of the central node using information from neighboring nodes and edges, effectively learning the statistical relationships between local structure and residue identity. This approach leverages the Boltzmann hypothesis of protein folding, where the probability of amino acids at specific positions relates to their free energy contributions:

[ -\ln\frac{P{AAj}}{P{AAi}} = \frac{1}{kB T} \Delta\Delta G{AAi \to AAj} ]

Where (P_{AA}) represents the probability of an amino acid type at a specific structural position, and (\Delta\Delta G) is the folding free energy change [7].

This SSL formulation enables Pythia to achieve state-of-the-art performance in predicting mutation effects on protein stability while requiring orders of magnitude less computation than traditional force field methods. The model demonstrates how domain-specific SSL pretext tasks based on biophysical principles can yield highly effective specialized representations.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Implementing SSL for protein research requires both computational resources and biological data assets. The following table catalogues essential "research reagents" for conducting SSL protein studies:

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Protein SSL

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Function and Utility | Access Information |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protein Sequence Databases | UniProt, UniRef, NCBI Protein | Provides millions of diverse sequences for SSL pre-training | Publicly available online |

| Protein Structure Databases | Protein Data Bank (PDB), AlphaFold Database | High-resolution structures for structure-based SSL | Publicly available online |

| Pre-trained SSL Models | ESM, ProtBERT, Pythia | Ready-to-use protein representations for downstream tasks | GitHub repositories, model hubs |

| Deep Learning Frameworks | PyTorch, TensorFlow, JAX | Infrastructure for developing and training SSL models | Open source |

| Specialized Protein ML Libraries | DeepChem, TorchProtein | Domain-specific tools for protein machine learning | Open source |

| Computational Resources | GPUs, TPUs, HPC clusters | Accelerated computing for training large SSL models | Institutional resources, cloud computing |

These resources provide the foundation for developing and applying SSL approaches to protein research. Pre-trained models offer immediate utility for researchers seeking to extract protein representations without undertaking expensive pre-training, while databases and software frameworks enable development of novel SSL methods tailored to specific research needs.

Visualization of SSL Workflows

The following diagram illustrates the complete SSL workflow for proteins, from pre-training through downstream application:

This workflow highlights the two-phase nature of SSL for proteins: (1) pre-training on unlabeled data through pretext tasks to learn general protein representations, followed by (2) fine-tuning on labeled data for specific applications. This paradigm has proven remarkably effective across diverse protein informatics tasks, establishing SSL as a cornerstone methodology in computational biology and drug discovery.

In the field of computational biology, self-supervised learning (SSL) has emerged as a powerful paradigm for extracting meaningful representations from large-scale, unlabeled biological data. For protein research, SSL models learn directly from the intrinsic patterns within core data modalities—sequences, structures, and interactions—to predict protein function, design novel proteins, and elucidate biological mechanisms. This guide provides a technical overview of these fundamental protein data modalities, detailing their sources, standardized formats, and their role as input for machine learning models, all within the context of self-supervised learning schemes.

Protein Sequence Data

Definition and Biological Basis

The protein sequence is the most fundamental data modality, representing the linear chain of amino acids that form the primary structure of a protein. This sequence is determined by the genetic code and dictates how the protein will fold into its three-dimensional shape, which in turn governs its function [12]. Sequences are the most abundant and accessible form of protein data.

Major repositories provide access to millions of protein sequences, often with rich functional annotations. These databases are foundational for training large-scale protein language models.

Table 1: Major Protein Sequence Databases

| Database Name | Provider/Platform | Key Features | Data Sources |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protein Database [13] [14] | NCBI | Aggregated protein sequences from multiple sources | GenBank, RefSeq, SwissProt, PIR, PRF, PDB |

| Reference Sequence (RefSeq) [13] | NCBI | Curated, non-redundant sequences providing a stable reference | Genomic DNA, transcript (RNA), and protein sequences |

| Identical Protein Groups [13] | NCBI | Consolidated records to target searches and identify specific proteins | GenBank, RefSeq, SwissProt, PDB |

| Swiss-Prot (via UniProt) | N/A | Manually annotated and reviewed protein sequences | Literature and curator-evaluated computational analysis |

Sequence Data as Model Input

In SSL, sequence data is typically processed into a numerical format that models can learn from. Common featurization methods include:

- One-Hot Encoding: A simple vector representation where each amino acid in a sequence is represented as a vector of 20 bits (19 zeros and a single 1), corresponding to the 20 standard amino acids.

- Amino Acid Physicochemical Properties (AAindex): Represents sequences using quantitative properties of amino acids like hydrophobicity, charge, and size [15].

- Embeddings from Protein Language Models (pLMs): Modern pLMs like ESM (Evolutionary Scale Modeling) [15] [16] [12] are pre-trained on millions of sequences using self-supervised objectives (e.g., masked token prediction). These models generate dense, contextual vector representations (embeddings) for each residue or entire sequences, capturing evolutionary and functional information.

Protein Structure Data

Definition and Biological Significance

Protein structure describes the three-dimensional arrangement of atoms in a protein molecule. The principle that "sequences determine structures, and structures determine functions" [12] underscores its critical importance. Structures provide direct insight into functional mechanisms, binding sites, and molecular interactions.

Experimental structures are determined using techniques like X-ray crystallography, NMR spectroscopy, and cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM). The rise of computational predictions, most notably AlphaFold 2, has dramatically expanded the universe of available protein structures [12].

Table 2: Key Protein Structure Resources

| Resource Name | Provider/Platform | Content Type | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| RCSB Protein Data Bank (PDB) [17] | RCSB PDB | Experimentally-determined 3D structures | Primary archive for structural data; provides visualization and analysis tools |

| AlphaFold DB [12] [17] | EMBL-EBI | Computed Structure Models (CSMs) | High-accuracy predicted structures for vast proteomes |

| ModelArchive [17] | N/A | Computed Structure Models (CSMs) | A repository for computational models |

PDB File Format and Featurization

The Protein Data Bank (PDB) file format is a standard textual format for describing 3D macromolecular structures [18] [19]. Though now supplemented by the newer PDBx/mmCIF format, it remains widely used. The format consists of fixed-column width records, each providing specific information.

Table 3: Essential Record Types in the PDB File Format [18]

| Record Type | Description | Key Data Contained |

|---|---|---|

| ATOM | Atomic coordinates for standard residues (amino acids, nucleic acids) | X, Y, Z coordinates (Å), occupancy, temperature factor, element symbol |

| HETATM | Atomic coordinates for nonstandard residues (inhibitors, cofactors, ions, solvent) | Same as ATOM records |

| TER | Indicates the end of a polymer chain | Chain identifier, residue sequence number |

| HELIX | Defines the location and type of helices | Helix serial number, start/end residues, helix type |

| SHEET | Defines the location and strand relationships in beta-sheets | Strand number, start/end residues, sense relative to previous strand |

| SSBOND | Defines disulfide bond linkages between cysteine residues | Cysteine residue chain identifiers and sequence numbers |

For model input, structural data is converted into numerical features. Common approaches include:

- Atomic Coordinate Tensors: Directly using the 3D (x, y, z) coordinates of atoms as input for geometric deep learning models.

- Distance Maps: Creating 2D matrices representing the distances between each pair of residues in the structure.

- Point Clouds: Treating atoms as points in 3D space, enabling the use of architectures like PointNet [16].

- Graph Representations: Representing a structure as a graph where nodes are amino acids (or atoms) and edges represent spatial proximity or chemical bonds. This is then processed by Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) [16] [12].

Diagram: From PDB File to Machine Learning Input. The workflow demonstrates how raw PDB files are parsed into different structural representations suitable for deep learning models.

Protein Interaction Data

Definition and Functional Role

Protein-protein interactions (PPIs) are the physical contacts between two or more proteins, specific and evolved for a particular function [20]. PPIs are crucial for virtually all cellular processes, including signal transduction, metabolic regulation, immune responses, and the formation of multi-protein complexes [20] [16]. Mapping PPIs into networks provides invaluable insights into functional organization and disease pathways [20].

Experimental Methods for PPI Detection

High-throughput experimental techniques are the primary sources for large-scale PPI data.

Table 4: Key Experimental Methods for Detecting PPIs [20]

| Method | Principle | Type of Interaction Detected | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yeast Two-Hybrid (Y2H) | Reconstitution of a transcription factor via bait-prey interaction in vivo [20]. | Direct, binary physical interactions. | Simple; detects transient interactions; system of choice for high-throughput screens [20]. | High false positive/negative rate; cannot detect membrane protein interactions well [20]. |

| Tandem Affinity Purification Mass Spectrometry (TAP-MS) | Two-step purification of a protein complex followed by MS identification of components [20]. | Direct and indirect associations (co-complex). | Identifies multi-protein complexes; high-confidence interactions. | In vitro method; transient interactions may be lost; does not directly infer binary interactions [20]. |

| Co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP) | Antibody-based purification of a protein and its binding partners [20]. | Direct and indirect associations (co-complex). | Works with native proteins and conditions. | Same limitations as TAP-MS; antibody specificity issues. |

Diagram: Key Experimental Workflows for PPI Detection. This outlines the core processes for Y2H and AP-MS, the two main high-throughput methods.

PPI Databases and Computational Prediction

Specialized databases curate PPI data from experimental studies. Given the limitations of experiments, computational prediction is a vital and active field.

- Databases: The STRING database is a widely used resource for known and predicted PPIs, often used to construct benchmark datasets for ML models [16]. NCBI's HIV-1, Human Protein Interaction Database is an example of a focused, pathogen-specific resource [13].

- Computational Prediction with SSL: Modern SSL approaches for PPI prediction often use multi-modal learning, integrating sequence, structure, and network data.

- Sequence-based Features: pLM embeddings, amino acid composition, and evolutionary information [16].

- Structure-based Features: If available, protein structures provide direct spatial information about potential interaction interfaces.

- Network-based Features: Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) can learn from the topology of existing PPI networks to predict new interactions. Models like MESM use GNNs, GATs, and SubgraphGCNs to learn from global and local network structures [16].

Integrated Multimodal Approaches and SSL Frameworks

The most advanced self-supervised learning frameworks in protein science move beyond single modalities to integrate sequence, structure, and sometimes interaction data. This multimodal approach allows models to capture complementary information, leading to more robust and generalizable representations.

Multimodal Model Architectures

- MESM (Multimodal Encoding Subgraph Model): A deep learning method that uses separate autoencoders to extract features from protein sequences (SVAE), structures (VGAE), and 3D point clouds (PAE). A Fusion Autoencoder (FAE) then integrates these multimodal features for enhanced PPI prediction [16].

- STELLA: A multimodal large language model (LLM) that uses ESM3 as a unified encoder for protein sequence and structure. It integrates these representations with a natural language LLM to predict protein functions and enzyme-catalyzed reactions based on user prompts [12].

- HyLightKhib: While focused on predicting post-translational modification sites, this framework exemplifies the hybrid feature strategy, combining ESM-2 sequence embeddings, Composition-Transition-Distribution (CTD) descriptors, and physicochemical properties (AAindex) for a comprehensive representation [15].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 5: Essential Computational Tools and Resources for Protein Data Research

| Tool/Resource Name | Type | Primary Function | Relevance to SSL |

|---|---|---|---|

| ESM-3 (Evolutionary Scale Modeling 3) [12] | Protein Language Model | Unified sequence-structure encoder and generator. | Provides foundational, general-purpose protein representations for downstream tasks. |

| RCSB PDB Protein Data Bank [17] | Database & Web Portal | Access, visualize, and analyze experimental 3D protein structures. | Source of high-quality structural data for training and benchmarking. |

| NCBI Protein Database [13] [14] | Database | Comprehensive repository of protein sequences from multiple sources. | Primary source of sequence data for pre-training pLMs. |

| AlphaFold DB [12] [17] | Database | Repository of highly accurate predicted protein structures. | Expands structural coverage for proteomes, enabling large-scale structural studies. |

| STRING [16] | Database | Database of known and predicted Protein-Protein Interactions. | Provides network data for training and evaluating PPI prediction models. |

| LightGBM [15] | Machine Learning Library | Gradient boosting framework for classification/regression. | High-performance classifier for tasks like PTM site prediction using extracted features. |

| Graph Neural Network (GNN) Libraries (e.g., PyTorch Geometric) | Machine Learning Library | Implementations of graph neural network architectures. | Essential for building models that learn from PPI networks or graph-based structural representations. |

| Cn3D [13] | Structure Viewer | Visualization of 3D structures from NCBI's Entrez. | Critical for interpreting and validating model predictions related to structure. |

Protein sequences, structures, and interactions constitute the core data modalities driving innovation in computational biology. The self-supervised learning paradigm leverages the vast, unlabeled data available in these modalities to learn powerful, generalizable representations. As the field progresses, the integration of these modalities through sophisticated multimodal architectures is paving the way for a more comprehensive and predictive understanding of protein biology, with profound implications for drug discovery, functional annotation, and synthetic biology.

The explosion of biological data, from protein sequences to single-cell genomics, has created a critical need for machine learning methods that can learn from limited labeled examples. Self-supervised learning (SSL) has emerged as a powerful paradigm that bridges the gap between supervised and unsupervised learning, particularly for biological applications where labeled data is scarce but unlabeled data is abundant. Unlike supervised learning, which requires extensive manually-annotated datasets, and unsupervised learning, which focuses solely on inherent data structures without task-specific guidance, SSL creates its own supervisory signals from the data itself [21] [22]. This approach has demonstrated remarkable success across diverse biological domains, from protein fitness prediction to single-cell analysis and gene-phenotype associations [23] [24] [25]. Within protein research specifically, SSL enables researchers to leverage the vast quantities of available unlabeled protein sequences and structures to build foundational models that can be fine-tuned for specific downstream tasks with minimal labeled data, thereby accelerating discovery in protein engineering and drug development.

Core Conceptual Differences Between Learning Paradigms

The fundamental distinction between learning paradigms lies in their relationship with data labels and their learning objectives. Supervised learning relies completely on labeled datasets, where each training example is paired with a corresponding output label. The model learns to map inputs to these known outputs, making it powerful for specific prediction tasks but heavily dependent on expensive, manually-curated labels. In biological contexts, this often becomes a bottleneck due to the complexity and cost of experimental validation [11].

Unsupervised learning operates without any labels, focusing exclusively on discovering inherent structures, patterns, or groupings within the data. Common applications include clustering similar protein sequences or dimensionality reduction for visualization. While valuable for exploration, these methods lack the ability to make direct predictions about specific properties or functions [22].

Self-supervised learning occupies a middle ground, creating its own supervisory signals from unlabeled data through pretext tasks. The model learns rich, general-purpose representations by solving these designed tasks, then transfers this knowledge to downstream problems with limited labeled data [24] [26]. This approach is particularly powerful in biology where unlabeled protein sequences, structures, and genomic data are abundant, but specific functional annotations are sparse.

Table 1: Core Characteristics of Machine Learning Paradigms in Biological Research

| Paradigm | Data Requirements | Primary Objective | Typical Biological Applications | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Supervised Learning | Large labeled datasets | Map inputs to known outputs | Protein function classification, fitness prediction | Limited by labeled data availability and cost |

| Unsupervised Learning | Only unlabeled data | Discover inherent data structures | Protein sequence clustering, cell population identification | No direct predictive capability for specific tasks |

| Self-Supervised Learning | Primarily unlabeled data + minimal labels | Learn transferable representations from pretext tasks | Protein pre-training, single-cell representation learning | Pretext task design crucial for performance |

Quantitative Performance Comparison Across Biological Domains

Empirical evidence demonstrates SSL's advantages in data efficiency and performance across multiple biological domains. In protein stability prediction, the self-supervised model Pythia achieved state-of-the-art prediction accuracy while increasing computational speed by up to 105-fold compared to traditional methods [23]. Pythia's zero-shot predictions demonstrated strong correlations with experimental measurements and higher success rates in predicting thermostabilizing mutations for limonene epoxide hydrolase.

In single-cell genomics, SSL has shown particularly strong performance in transfer learning scenarios. When analyzing the Tabula Sapiens Atlas (483,152 cells, 161 cell types), self-supervised pre-training on additional single-cell data improved macro F1 scores from 0.2722 to 0.3085, with particularly dramatic improvements for specific cell types - correctly classifying 6,881 of 7,717 type II pneumocytes compared to only 2,441 without SSL pre-training [24].

For gene-phenotype association prediction, SSLpheno addressed the critical challenge of limited annotations in the Human Phenotype Ontology database, which contains phenotypic annotations for only 4,895 genes out of approximately 25,000 human genes [25]. The method outperformed state-of-the-art approaches, particularly for categories with fewer annotations, demonstrating SSL's value for imbalanced biological datasets.

Table 2: Performance Benchmarks of SSL Methods Across Biological Applications

| Method | Domain | Base Performance | SSL-Enhanced Performance | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pythia [23] | Protein stability prediction | Varies by traditional method | State-of-the-art accuracy across benchmarks | 105x speed increase, zero-shot capability |

| SSL Single-Cell [24] | Cell-type prediction (Tabula Sapiens) | 0.2722 ± 0.0123 macro F1 | 0.3085 ± 0.0040 macro F1 | Improved rare cell type identification |

| SSLpheno [25] | Gene-phenotype associations | Outperformed by supervised methods with limited labels | Superior to state-of-the-art methods | Especially effective for sparsely annotated categories |

| Self-GenomeNet [26] | Genomic sequence tasks | Standard supervised training requires ~10x more labeled data | Matches performance with limited data | Robust cross-species generalization |

SSL Methodologies and Experimental Protocols in Protein Research

Structure-Based Protein SSL

Structure-aware protein SSL incorporates crucial structural information that sequence-only methods miss. The methodology typically involves:

Graph Construction: Represent protein structures as graphs where nodes correspond to amino acid residues and edges represent spatial relationships or chemical interactions [27].

Pre-training Tasks: Design self-supervised objectives that capture structural properties:

- Pairwise Residue Distance Prediction: Train the model to predict spatial distances between residue pairs, enforcing learning of tertiary structure constraints.

- Dihedral Angle Prediction: Predict backbone torsion angles to capture local folding patterns.

- Contrastive Learning: Create positive pairs through structure-preserving augmentations and negative pairs from different proteins [27].

Integration with Protein Language Models: Combine structural SSL with sequential pre-training through pseudo bi-level optimization, allowing information exchange between sequence and structure representations [27].

Fine-tuning: Transfer learned representations to downstream tasks like stability prediction or function classification with minimal task-specific labels.

Masked Autoencoder Approaches for Biological Sequences

Masked autoencoders have proven particularly effective for biological sequence data:

Multiple Masking Strategies: Implement diverse masking approaches:

- Random Masking: Randomly mask portions of the input sequence or features.

- Gene Programme Masking: Mask biologically meaningful gene sets.

- Isolated Masking: Target specific functional groups like transcription factors [24].

Reconstruction Objective: Train the model to reconstruct the original input from the masked version, forcing it to learn meaningful representations and dependencies within the data.

Multi-scale Prediction: For genomic sequences, predict targets of different lengths to capture both short- and long-range dependencies [26].

Architecture Design: Utilize encoder-decoder architectures where the encoder processes the masked input and the decoder reconstructs the original, with the encoder outputs used as representations for downstream tasks.

Research Reagent Solutions for SSL in Protein Studies

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Implementing SSL in Protein Research

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pythia [23] | Web Server/Software | Zero-shot protein stability prediction | Predicting ΔΔG changes for mutations |

| HPO Database [25] | Biological Database | Standardized phenotype ontology | Training data for gene-phenotype prediction |

| Protein Data Bank | Structure Repository | Experimental protein structures | Input for structure-aware SSL |

| UniProt/Swiss-Prot [25] | Protein Database | Curated protein sequence and functional data | Gene-to-protein mapping and feature extraction |

| Direct Coupling Analysis [11] | Statistical Method | Infer evolutionary constraints from MSA | Encoding evolutionary information in SSL |

| Multiple Sequence Alignment [11] | Bioinformatics Tool | Identify homologous sequences | Constructing evolutionary context for proteins |

| Graph Neural Networks [27] | Deep Learning Architecture | Process structured data like protein interactions | Structure-aware protein representation learning |

Implementation Workflow for Protein Fitness Prediction

SSL implementation for protein fitness prediction demonstrates the practical application of these methodologies:

The workflow begins with collecting evolutionarily related protein sequences and generating multiple sequence alignments to identify conserved regions [11]. The Direct Coupling Analysis (DCA) statistical model is then inferred from these alignments, serving dual purposes: predicting statistical energy of sequences in an unsupervised manner and encoding labeled sequences for supervised training [11]. During SSL pre-training, models learn general protein representations through pretext tasks like masked residue prediction, where portions of the input sequence are masked and the model must reconstruct them, forcing it to learn contextual relationships within protein sequences. For contrastive learning, positive pairs are created through sequence augmentations that preserve functional properties, while negative pairs come from different protein families [27]. Finally, the pre-trained model is fine-tuned on limited labeled fitness data, enabling accurate prediction of protein fitness and guiding protein engineering campaigns with minimal experimental data [11].

Self-supervised learning represents a paradigm shift in biological machine learning, offering a powerful alternative to traditional supervised and unsupervised approaches. By creating supervisory signals from unlabeled data, SSL models can learn rich, transferable representations that capture fundamental biological principles—from protein folding constraints to evolutionary patterns. The quantitative evidence across multiple domains demonstrates SSL's superior data efficiency, performance in low-label regimes, and ability to accelerate discovery in protein research and drug development. As biological data continues to grow exponentially, SSL methodologies will play an increasingly crucial role in extracting meaningful insights and advancing our understanding of biological systems.

Architectures and Applications: Implementing SSL for Protein Structure and Function

Protein Language Models (pLMs) represent a transformative innovation at the intersection of natural language processing (NLP) and computational biology, leveraging self-supervised learning paradigms to extract meaningful representations from unlabeled protein sequences. By treating protein sequences as strings of tokens analogous to words in human language, where the 20 common amino acids form the fundamental alphabet, these models capture evolutionary, structural, and functional patterns without explicit supervision [28] [29]. The exponential growth of publicly available protein sequence data, exemplified by databases such as UniRef and BFD containing tens of millions of sequences, has provided the essential substrate for training increasingly sophisticated pLMs [28] [30]. This technological advancement has fundamentally reshaped research methodologies across biochemistry, structural biology, and therapeutic development, enabling state-of-the-art performance in tasks ranging from structure prediction to novel protein design.

The conceptual foundation of pLMs rests upon the striking parallels between natural language and protein sequences. Just as human language exhibits hierarchical structure from characters to words to sentences with semantic meaning, proteins display organizational principles from amino acids to domains to full proteins with biological function [28]. This analogy permits the direct application of self-supervised learning techniques originally developed for NLP, particularly transformer-based architectures, to model the complex statistical relationships within protein sequence space. The resulting models serve as powerful feature extractors, generating contextual embeddings that encode rich biological information transferable to diverse downstream applications without task-specific training [30].

Architectural Foundations of Protein Language Models

Evolution of Model Architectures

The architectural landscape of pLMs has evolved significantly from initial non-transformer approaches to contemporary sophisticated transformer-based designs. Early models employed shallow neural networks like ProtVec, which applied word2vec techniques to amino acid k-mers, treating triplets of residues as biological "words" to generate distributed representations [28] [30]. Subsequent approaches incorporated recurrent neural architectures, with UniRep utilizing multiplicative Long Short-Term Memory networks (mLSTMs) and SeqVec employing ELMo-inspired bidirectional recurrent networks to capture contextual information across protein sequences [28]. However, these architectures faced limitations in parallelization capability and handling long-range dependencies, constraints that would eventually be addressed by transformer-based approaches [28].

The introduction of the transformer architecture marked a paradigm shift in protein representation learning, with most contemporary pLMs adopting one of three primary configurations. Encoder-only models, exemplified by the ESM series and ProtTrans, utilize BERT-style architectures to generate contextual embeddings for each residue position through masked language modeling objectives [28] [29]. Decoder-only models, including ProGen and ProtGPT2, employ GPT-style autoregressive architectures trained for next-token prediction, enabling powerful sequence generation capabilities [30] [29]. Encoder-decoder models adopt T5-style architectures for sequence-to-sequence tasks such as predicting complementary protein chains or functional modifications [30]. A notable architectural innovation emerged from Microsoft Research, where convolutional neural networks (CNNs) were implemented in the CARP model series, demonstrating performance comparable to transformer counterparts while offering linear scalability with sequence length compared to the quadratic complexity of attention mechanisms [31].

Key Architectural Components

The transformer architecture, foundational to most modern pLMs, incorporates several essential components that enable its exceptional performance on protein sequence data. The self-attention mechanism forms the core innovation, allowing the model to dynamically weight the importance of different residue positions when processing each token in the input sequence [29]. Multi-head attention extends this capability by enabling the model to simultaneously capture different types of relational information—such as structural, functional, and evolutionary constraints—under various representation subspaces [28] [29].

Positional encoding represents another critical component, as transformers lack inherent order awareness unlike recurrent networks. pLMs typically employ either absolute positional encodings (sinusoidal or learnable) or relative encodings such as Rotary Positional Encoding (RoPE) to inject information about residue positions within the sequence [30]. This capability has been progressively extended to handle increasingly long protein sequences, with early models truncating at 1,024 residues and contemporary models like Prot42 processing sequences up to 8,192 residues [30]. The feed-forward networks within each transformer layer apply position-wise transformations to refine representations, while residual connections and layer normalization stabilize the training process across deeply stacked architectures [29].

Table: Evolution of Protein Language Model Architectures

| Architecture Type | Representative Models | Key Characteristics | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Transformer | ProtVec, UniRep, SeqVec | Shallow embeddings, RNNs/LSTMs | Basic sequence classification, initial embeddings |

| Encoder-only | ESM series, ProtTrans, ProtBERT | Bidirectional context, MLM training | Structure prediction, function annotation, variant effect |

| Decoder-only | ProGen, ProtGPT2 | Autoregressive generation | De novo protein design, sequence completion |

| Encoder-Decoder | T5-based models | Sequence-to-sequence transformation | Scaffolding, binding site design |

| Convolutional | CARP series | Linear sequence length scaling | Efficient representation learning |

Self-Supervised Training Methodologies

Pre-training Objectives and Strategies

Protein language models employ diverse self-supervised objectives during pre-training to learn generalizable representations from unlabeled sequence data. Masked Language Modeling (MLM), adapted from BERT-style training, randomly masks portions of the input sequence (typically 15-20%) and trains the model to reconstruct the original amino acids based on contextual information [30] [29]. Advanced variations incorporate dynamic masking strategies, where masking patterns change across training epochs, and specialized objectives like pairwise MLM that capture co-evolutionary signals without requiring explicit multiple sequence alignments [28]. Autoregressive next-token prediction, utilized in decoder-only architectures, trains models to predict each successive residue given preceding context, enabling powerful generative capabilities [30].

Emerging training paradigms increasingly incorporate multi-task learning frameworks that combine multiple self-supervised objectives. The Ankh model series employs both MLM and protein sequence completion tasks to enhance generalization [30], while structure-aligned pLMs like SaESM2 incorporate contrastive learning objectives to align sequence representations with structural information from protein graphs [30]. Metalic leverages meta-learning across fitness prediction tasks, enabling rapid adaptation to new protein families with minimal parameters through in-context learning mechanisms [30]. These advanced training strategies progressively narrow the gap between sequence-based representations and experimentally validated structural and functional properties.

Data Curation and Scaling Laws

The performance of pLMs is fundamentally constrained by the quality and diversity of pre-training data. Current models primarily utilize comprehensive protein sequence databases including UniRef (50/90/100), Swiss-Prot, TrEMBL, and metagenomic datasets like BFD, which collectively encompass hundreds of millions of natural sequences across diverse organisms and environments [28] [30]. Recent investigations into scaling laws for pLMs have revealed that, within fixed computational budgets, model size should scale sublinearly while dataset token count should scale superlinearly, with diminishing returns observed after approximately a single pass through available datasets [30]. This finding suggests potential compute inefficiencies in many widely-used pLMs and indicates opportunities for optimization through more balanced model-data scaling.

Table: Key Pre-training Datasets for Protein Language Models

| Dataset | Sequence Count | Key Characteristics | Representative Models Using Dataset |

|---|---|---|---|

| UniRef50 | ~45 million | Clustered at 50% identity | ESM-1b, ProtTrans, CARP |

| UniRef90 | ~150 million | Clustered at 90% identity | ESM-2, ESM-3 |

| BFD | >2 billion | Metagenomic sequences | ProtTrans, ESM-2 |

| Swiss-Prot | ~500,000 | Manually annotated | Early models, specialized fine-tuning |

Experimental Frameworks and Downstream Applications

Structure Prediction and Validation

Protein structure prediction represents one of the most significant success stories for pLMs, with models like ESMFold and the Evoformer component of AlphaFold demonstrating remarkable accuracy in predicting three-dimensional structures from sequence information alone [30]. The experimental protocol for evaluating structural prediction capabilities typically involves benchmark datasets such as CAMEO (Continuous Automated Model Evaluation) and CASP (Critical Assessment of Structure Prediction), with performance quantified through metrics including TM-score (Template Modeling Score), RMSD (Root Mean Square Deviation), and precision of long-range contacts (Precision@L) [30]. The Evoformer architecture, which integrates both multiple sequence alignments and structural supervision through distogram losses, has achieved exceptional performance with Precision@L scores of approximately 94.6% for contact prediction [30].

The typical workflow begins with generating embeddings for target sequences using pre-trained pLMs, which are then processed through specialized structural heads that translate residue-level representations into spatial coordinates. For proteins with known homologs, methods like AlphaFold incorporate explicit evolutionary information from MSAs, while "evolution-free" approaches like ESMFold demonstrate that single-sequence embeddings from sufficiently large pLMs can capture structural information competitive with MSA-dependent methods [30]. Experimental validation typically involves comparison to ground truth structures obtained through X-ray crystallography or cryo-EM, with TM-scores >0.8 generally indicating correct topological predictions.

Function Prediction and Engineering Applications

pLMs have revolutionized computational function prediction by enabling zero-shot transfer learning, where models pre-trained on general sequence databases are directly applied to specific functional annotation tasks without further training. Standard evaluation benchmarks include TAPE (Tasks Assessing Protein Embeddings), CAFA (Critical Assessment of Function Annotation), and ProteinGym, which assess performance across diverse functional categories including enzyme commission numbers, Gene Ontology terms, and antibiotic resistance [30]. Experimental protocols typically involve extracting embeddings from pre-trained pLMs, followed by training shallow classifiers (e.g., logistic regression, multilayer perceptrons) on labeled datasets, with performance measured through accuracy, F1 scores, and area under ROC curves [30].

In protein engineering applications, pLMs enable both directed evolution and de novo design through sequence generation and fitness prediction. The experimental framework for validating designed proteins involves in silico metrics such as sequence recovery rates (similarity to natural counterparts) and computational fitness estimates, followed by experimental validation through heterologous expression, purification, and functional assays [30]. Recent approaches like LM-Design incorporate lightweight structural adapters for structure-informed sequence generation, while ProtFIM employs fill-in-middle objectives for flexible protein engineering tasks [30]. These methodologies have demonstrated remarkable success, with experimental validation reporting identification of nanomolar binders for therapeutic targets like EGFR within hours of computational screening [30].

Table: Standard Evaluation Benchmarks for Protein Language Models

| Application Domain | Primary Benchmarks | Key Evaluation Metrics |

|---|---|---|

| Structure Prediction | CAMEO, CASP, SCOP | TM-score, RMSD, Precision@L |

| Function Prediction | TAPE, CAFA, ProteinGym | Accuracy, F1, auROC |

| Protein Engineering | CATH, GB1, FLIP | Sequence recovery, fitness scores |

| Mutation Effects | ProteinGym, Clinical Variants | Spearman correlation, AUC |

Core Software and Model Implementations

The practical application of pLMs in research environments requires access to specialized software tools and pre-trained model implementations. The ESM (Evolutionary Scale Modeling) model series, developed by Meta AI, provides comprehensive codebases and pre-trained weights for models ranging from the 650M parameter ESM-1b to the 15B parameter ESM-3, with implementations available through PyTorch and Hugging Face transformers library [28] [29]. The ProtTrans framework offers similarly accessible implementations of BERT-style models trained on massive protein sequence datasets, while the CARP (Convolutional Autoencoding Representations of Proteins) series provides efficient alternatives based on convolutional architectures [31] [28]. These resources typically include inference pipelines for generating embeddings, fineuning scripts for downstream tasks, and visualization utilities for interpreting model outputs.

Specialized frameworks have emerged to address specific research applications. DeepChem integrates pLM capabilities with molecular machine learning for drug discovery pipelines, while OpenFold provides open-source implementations of structure prediction models for academic use [30]. The ProteinGym benchmark suite offers standardized evaluation frameworks for comparing model performance across diverse tasks, including substitution effect prediction and fitness estimation [30]. For generative applications, ProtGPT2 and ProGen provide trained models for de novo protein sequence generation, with fine-tuning capabilities for targeting specific structural or functional properties [29].

Computational Requirements and Optimization

Deploying pLMs in research environments necessitates careful consideration of computational resources and optimization strategies. While large models like the 15B parameter ESM-3 require significant GPU memory (typically 40-80GB) for inference and fine-tuning, distilled versions like DistilProtBERT offer more accessible alternatives with minimal performance degradation [28]. Recent optimization advances include flash attention implementations that reduce memory requirements for long sequences, and quantization techniques that enable inference on consumer-grade hardware [30]. For processing massive protein databases, tools like bio-embeddings provide pipelined workflows that efficiently generate embeddings across distributed computing environments.

Table: Essential Research Resources for Protein Language Modeling

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Models | Primary Function | Access Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-trained Models | ESM-1b/2/3, ProtTrans, CARP | Generate protein embeddings | PyTorch/Hugging Face |

| Benchmark Suites | TAPE, ProteinGym, CAFA | Standardized performance evaluation | GitHub repositories |

| Structure Prediction | ESMFold, OpenFold | 3D structure from sequence | Web servers, local install |

| Generation & Design | ProtGPT2, ProGen | De novo protein sequence generation | GitHub, API access |

| Visualization | PyMOL plugins, Embedding Projectors | Interpret embeddings and predictions | Various platforms |

Future Directions and Emerging Challenges

The rapid evolution of pLMs faces several significant challenges that will shape future research directions. Data quality and diversity limitations persist, with current training sets exhibiting biases toward well-studied organisms and underrepresentation of certain structural motifs like β-sheet-rich proteins [30]. Computational requirements present substantial barriers to broader adoption, though recent work on scaling laws suggests potential for more efficient architectures trained with optimal compute budgets [30]. Interpretability remains another critical challenge, as the biological significance of internal representations is often opaque, though emerging techniques like automated neuron labeling show promise for generating human-understandable explanations of model decisions [30].

Future research directions point toward several transformative developments. Multimodal integration represents a particularly promising avenue, with models like DPLM-2 already demonstrating unified sequence-structure modeling through discrete diffusion processes and lookup-free coordinate quantization [30]. Instruction-tuning approaches are emerging that enable natural language guidance of protein design and analysis tasks, making pLMs accessible to non-specialist researchers [30]. Architectural innovations continue to push boundaries, with models like Prot42 extending sequence length capabilities to 8,192 residues and beyond, enabling modeling of complex multi-domain proteins and large complexes [30]. As these technologies mature, pLMs are poised to become increasingly central to biological discovery and therapeutic development, potentially enabling rapid response to emerging pathogens and design of novel biocatalysts for environmental and industrial applications.

The integration of self-supervised learning (SSL) with graph neural networks (GNNs) has ushered in a transformative paradigm for analyzing biomolecular structures, particularly proteins. This approach addresses a fundamental challenge in computational biology: leveraging the vast and growing repositories of unlabeled protein structural data to enhance our understanding of function, interaction, and dynamics. Structure-aware SSL frameworks enable the learning of rich, contextual representations of proteins by formulating predictive tasks that exploit the intrinsic geometric relationships within molecular structures—specifically, atomic distances and angles—without requiring experimentally-determined labels [32] [33]. This technical guide explores the core principles, methodologies, and applications of GNN-based SSL for distance and angle prediction within the broader context of a research thesis on self-supervised learning schemes for protein data.

The prediction of inter-atomic distances and bond angles is not merely a technical exercise; it provides a foundational geometric constraint that governs protein folding, stability, and function. Accurate estimation of these parameters enables the reconstruction of reliable 3D structures from sequence information alone, facilitates the prediction of mutation effects on protein stability, and illuminates the molecular determinants of functional interactions [23] [34]. By framing these predictions as self-supervised pre-training tasks, GNNs can learn transferable knowledge about the physical and chemical rules of structural biology, which subsequently enhances performance on downstream predictive tasks such as function annotation, interaction partner identification, and stability change quantification, even with limited labeled data [23] [32] [34].

Theoretical Foundations

Graph Representation of Protein Structures

Proteins are inherently graph-structured entities. In computational models, this representation can be realized at different levels of granularity, each serving distinct predictive purposes. The residue-level graph is particularly prevalent for predicting protein-protein interactions (PPIs) and coarse-grained functional sites [35] [34]. In this representation, nodes correspond to amino acid residues, and edges are formed between residues that are spatially proximate within the folded 3D structure, typically defined by a threshold distance between their atoms (e.g., 8-10 Å) [35]. This formulation captures the residue contact network, essential for understanding functional dynamics.

For tasks requiring atomic detail, such as quantifying the impact of mutations on protein stability or modeling precise molecular interactions, an atomic-level graph is more appropriate [23] [36]. Here, nodes represent individual atoms, and edges correspond to chemical bonds or, in some implementations, spatial proximity within a defined cutoff. This fine-grained representation allows GNNs to model the precise steric and electronic interactions that dictate molecular stability and binding affinity. The multi-scale nature of protein structure necessitates that the choice of graph representation aligns with the specific biological question and the resolution of the available data [36].

Self-Supervised Learning on Graphs

Self-supervised learning on molecular graphs aims to learn generalizable representations by designing pretext tasks that force the model to capture fundamental structural and chemical principles. Two dominant SSL paradigms are particularly relevant for distance and angle prediction: contrastive learning and pretext task-based learning [33].