Rational Protein Design and Site-Directed Mutagenesis: A Modern Guide for Researchers

This article provides a comprehensive overview of rational protein design, with a specific focus on the pivotal role of site-directed mutagenesis (SDM).

Rational Protein Design and Site-Directed Mutagenesis: A Modern Guide for Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of rational protein design, with a specific focus on the pivotal role of site-directed mutagenesis (SDM). Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational principles of using detailed protein structure and function knowledge to guide targeted mutations. The scope ranges from core methodologies and practical applications—including enhancing enzyme thermostability, activity, and specificity for industrial and therapeutic use—to advanced troubleshooting of SDM protocols. It also covers the validation of designed variants and offers a comparative analysis with other protein engineering strategies like directed evolution, concluding with an outlook on the transformative impact of computational tools and automation on the future of biomedical research.

The Principles and Power of Rational Protein Design

Rational protein design represents a foundational methodology in protein engineering that employs precise, knowledge-driven modifications to alter protein function. Unlike stochastic methods, this approach leverages detailed structural and functional insights to predict beneficial amino acid substitutions, typically achieved via site-directed mutagenesis (SDM). This application note delineates the core principles, methodologies, and practical protocols of rational design, contextualized within the broader paradigm of site-directed mutagenesis research. It provides a detailed framework for researchers and drug development professionals to implement these strategies for developing novel biocatalysts, therapeutics, and research tools.

Protein engineering is a powerful biotechnological process focused on creating new enzymes or proteins and improving the functions of existing ones by manipulating their natural macromolecular architecture [1]. Within this field, rational protein design stands as a classical method characterized by its hypothesis-driven nature. The core premise of rational design is the application of existing structural, functional, and mechanistic knowledge of a target protein to make precise, targeted changes to its amino acid sequence [1] [2]. This strategy aims to produce proteins with enriched activities, such as enhanced thermostability, catalytic efficiency, or altered substrate specificity, by focusing mutations on key regions known to influence these properties.

This approach contrasts sharply with methods like directed evolution, which introduces random mutations across the gene and relies on high-throughput screening to identify improved variants without requiring prior structural knowledge [1]. Rational design produces smaller, more focused mutant libraries, increasing the likelihood that screened variants will possess the desired function [2]. The method's success is intrinsically tied to the depth and accuracy of the available protein data, making it a highly focused and efficient strategy when such information is available.

Rational Design in the Context of Protein Engineering Strategies

The landscape of protein engineering is diverse, encompassing multiple strategies. Rational design is one of several key methodologies, each with distinct advantages and applications. The following table provides a comparative overview of major protein engineering approaches.

Table 1: Key Methods in Protein Engineering

| Method | Core Principle | Knowledge Requirement | Key Advantage | Typical Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rational Design | Site-directed mutagenesis based on structural/functional knowledge [1] | High (3D structure, mechanism) [1] | Precise; produces small, focused libraries [2] | Engineering protein-based vaccines, antibodies, and enzymes [1] |

| Directed Evolution | Random mutagenesis followed by screening/selection; mimics natural evolution [1] | Low | Does not require prior structural information [1] | General protein optimization when structural data is limited |

| Semi-Rational Design | Combines rational and directed evolution; uses computation to target specific sites for randomization [1] [2] | Moderate (e.g., bioinformatic data) | Balances library size and quality; increased chance of success [1] | Creating biocatalysts with wider substrate range and stability [1] |

| De Novo Design | Creating proteins with specific structural/functional properties from scratch [1] [3] | Principles of protein folding | Generates entirely novel proteins and folds [3] | Designing binders, symmetric assemblies, and new protein topologies [3] |

A specialized form of rational design is site-saturation mutagenesis (SSM), which randomizes a specific codon, or short sequence of codons, to produce libraries of mutants with all possible amino acid substitutions at the targeted positions [2]. While it creates a larger library than typical rational design, it remains semi-rational because the randomization is focused on specific, pre-selected sites, making it more efficient than sequence-agnostic random mutagenesis [2].

Core Principles and Workflow of Rational Protein Design

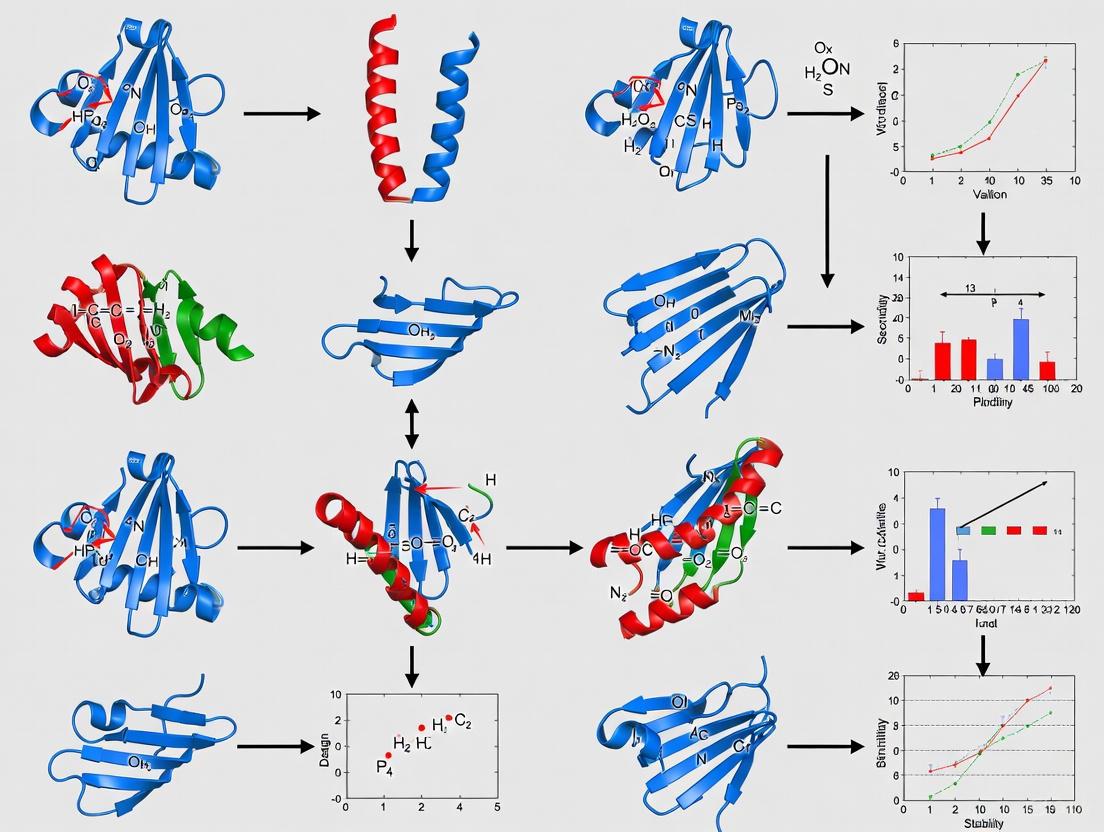

The rational design process is a systematic sequence of stages that transforms knowledge of a protein into a tested, improved variant. The workflow can be visualized as a logical pathway from target analysis to experimental validation.

Experimental Workflow for Rational Protein Design

The following diagram outlines the key stages in a rational protein design project, from initial target identification to the final experimental validation of designed variants.

Detailed Protocol for Site-Directed Mutagenesis

This protocol provides a step-by-step methodology for performing PCR-based site-directed mutagenesis, a cornerstone technique of rational protein design.

Objective: To introduce a specific point mutation into a gene of interest. Principle: Desired point mutations are incorporated into primers that are used to amplify the entire plasmid in a PCR reaction. The PCR product, containing the nicked plasmid with the mutation, is then transformed into a host strain where the nicks are repaired [2].

Materials:

- Template DNA: Plasmid containing the wild-type gene of interest.

- Oligonucleotide Primers: Forward and reverse primers designed to contain the desired mutation in their sequence.

- High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase: An enzyme suitable for PCR amplification of plasmids (e.g., PfuUltra, KAPA HiFi).

- Restriction Enzyme (DpnI): Specifically digests methylated and hemi-methylated DNA (used to selectively digest the parental DNA template).

- Competent Cells: Chemically or electrocompetent E. coli cells for transformation.

- LB Agar Plates: Containing the appropriate antibiotic for plasmid selection.

Procedure:

- Primer Design:

- Design primers that are complementary to the template sequence and anneal back-to-back.

- The desired mutation (base substitution, insertion, or deletion) should be located in the middle of the primer sequence.

- Primers should typically be 25-45 nucleotides long with a GC content of ~40-60%.

- The melting temperature (Tm) should be ≥78°C.

- Phosphorylation of the 5'-end is recommended if the polymerase used does not add an adenosine overhang.

PCR Amplification:

- Set up a PCR reaction mix containing:

- Template DNA (10-100 ng)

- Forward and reverse mutagenic primers (0.1-1 µM each)

- dNTPs

- High-fidelity DNA polymerase and corresponding buffer

- Run a thermal cycling program as follows:

- Initial Denaturation: 95°C for 2 minutes

- Denaturation: 95°C for 20 seconds

- Annealing: 55-65°C (based on Tm) for 30 seconds → 25-30 cycles

- Extension: 72°C for 2-6 minutes (depending on plasmid length)

- Final Extension: 72°C for 5-10 minutes

- Set up a PCR reaction mix containing:

Digestion of Template DNA:

- Following PCR, add 1 µL of DpnI restriction enzyme directly to the PCR tube.

- Mix gently and incubate at 37°C for 1-2 hours to digest the methylated parental DNA template.

Transformation:

- Transform 1-5 µL of the DpnI-treated DNA into 50 µL of competent E. coli cells following standard transformation protocols (heat-shock or electroporation).

Screening and Verification:

- Plate the transformed cells onto LB agar plates with the appropriate antibiotic.

- After overnight growth, pick several colonies for sequence verification to confirm the presence of the desired mutation and the absence of unintended mutations.

Advanced Applications and Data-Driven Extensions

Rational design is increasingly being augmented by artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML), leading to more powerful and efficient engineering pipelines. These advanced methods help bridge knowledge gaps, such as predicting the complex conformational changes that occur during molecular binding [1].

One innovative approach, termed Omni-Directional Multipoint Mutagenesis (ODM), fine-tunes a pre-trained protein language model (BERT) on homologous sequences of a target protein to generate thousands of mutant sequences [4]. A key screening metric in this pipeline is "Weakness screening" (Ws), which is based on the "Barrel Theory." This theory posits that the lowest predicted probability mutation in a sequence—the "shortest plank"—has the greatest impact on overall protein activity. By ranking mutants based on their highest minimal probability value, researchers can efficiently select the most promising variants for experimental testing [4].

The following table summarizes experimental outcomes from a study that employed this ODM pipeline to engineer two different enzymes, demonstrating the success rate achievable with advanced rational design methods.

Table 2: Experimental Outcomes from an AI-Augmented Rational Design Pipeline [4]

| Target Enzyme | Property Engineered | Screening Method | Success Rate | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protease (ZH1) | Thermostability | Weakness screening (Ws) & thermostability models | 62.5% of mutants showed increased thermostability | AI-driven ranking effectively identified stabilized variants. |

| Lysozyme (G732) | Bacteriolytic Activity | Weakness screening (Ws) & biological indicators | 50% of mutants showed increased activity | Introduction of additional basic residues enhanced function. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of rational protein design relies on a suite of essential reagents and computational tools. The following table details key materials and their functions.

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Tools for Rational Protein Design

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Description | Application in Rational Design |

|---|---|---|

| High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase | PCR enzyme with low error rate for accurate amplification. | Critical for performing site-directed mutagenesis PCR to introduce specific mutations without introducing random errors [2]. |

| DpnI Restriction Enzyme | Cuts methylated and hemi-methylated DNA. | Used post-PCR to selectively digest the original, methylated parental DNA template, enriching for the newly synthesized, mutated plasmid [2]. |

| Competent E. coli Cells | Bacterial cells rendered permeable for DNA uptake. | Used for transforming the mutated plasmid DNA after PCR and DpnI digestion to amplify the plasmid and produce the mutant protein [2]. |

| Crystallography & Modeling Software | Determines and visualizes 3D protein structures (e.g., X-ray crystallography, AlphaFold2, RoseTTAFold) [1]. | Provides the structural insights essential for identifying key residues to mutate in rational design [1] [3]. |

| Structure Prediction Networks (e.g., RoseTTAFold, AlphaFold2) | Deep-learning networks for predicting protein structure from sequence [3]. | Informs the initial design hypothesis and is used for in silico validation of designed protein structures [3]. |

| Generative Models (e.g., RFdiffusion, Protein BERT) | AI models that can generate new protein structures or sequences based on constraints [3] [4]. | Enables de novo design of protein binders or scaffolds, and generates focused mutant libraries for specific properties [4]. |

Rational protein design remains a powerful and precise approach within protein engineering, distinguished by its foundational reliance on structural and functional knowledge. The method, centered on site-directed mutagenesis, allows for the direct testing of hypotheses about protein structure-function relationships. While the requirement for prior knowledge can be a limitation, the integration of advanced computational tools—from structure prediction networks like AlphaFold2 and RoseTTAFold to generative AI models—is dramatically expanding the scope and success rate of rational design. As these data-driven technologies continue to mature, they are forging a new paradigm that merges the precision of rationality with the explorative power of computation, thereby accelerating the development of novel enzymes, therapeutics, and biomaterials.

Site-directed mutagenesis (SDM) is a fundamental in vitro method that enables researchers to create specific, targeted changes in double-stranded plasmid DNA [5]. This technique serves as a cornerstone in molecular biology and protein engineering, allowing for the precise introduction of nucleotide substitutions, insertions, or deletions at defined locations within a known DNA sequence [6]. Within the context of rational protein design, SDM provides the essential experimental link between computational models and functional validation, permitting researchers to systematically test hypotheses about protein structure-function relationships.

The versatility of SDM extends across multiple research applications, including investigating protein activity changes resulting from DNA manipulation, screening for mutations with desired properties at the DNA, RNA, or protein level, and introducing or removing critical molecular features such as restriction endonuclease sites or affinity tags [5]. The development of SDM methodologies has evolved significantly from early approaches that relied on specialized bacterial strains to contemporary PCR-based methods that utilize standard primers and high-fidelity polymerases, dramatically increasing the accessibility and efficiency of protein engineering workflows [5].

Core Principles and Mechanisms

Site-directed mutagenesis operates on the principle of using custom oligonucleotide primers to confer desired mutations during amplification of a DNA template [5]. The most widely-used methods today employ inverse PCR with standard primers that can be designed in either overlapping or back-to-back orientations [5]. These approaches differ in their mechanisms and resulting products, with each offering distinct advantages for particular experimental needs.

In overlapping primer design, the primers are complementary to adjacent regions of the plasmid and include the desired mutation at their centers. This approach produces a PCR product that re-circularizes to form a doubly-nicked plasmid, which can be directly transformed into E. coli despite lower transformation efficiency compared to non-nicked plasmids [5]. In contrast, back-to-back primer design positions primers to bind on opposite strands facing away from each other, resulting in exponential amplification and generation of significantly more desired product [5]. This method produces linear, double-stranded DNA that requires circularization prior to transformation but offers the advantage of creating non-nicked plasmids with higher transformation efficiency [5].

Following PCR amplification, a critical step in the SDM workflow involves template removal using the restriction endonuclease DpnI, which selectively digests methylated DNA (i.e., the original plasmid propagated and isolated from E. coli) [7]. Because PCR products are generated in vitro, they lack methylation and remain resistant to DpnI activity, enabling selective elimination of the parental template [7] [8]. The resulting mutated plasmid is then transformed into competent E. coli cells, where cellular machinery repairs nicks and enables propagation of the engineered DNA [9].

Experimental Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the generalized site-directed mutagenesis workflow from primer design to sequence verification:

Critical Experimental Considerations

Primer Design Strategies

The most critical component for successful site-directed mutagenesis is proper primer design [7]. Multiple factors must be considered during this process, with the first consideration being the relative location of the two primers. Primers designed back-to-back have the benefit of exponential amplification but also propagate polymerase errors exponentially; therefore, only the highest fidelity enzymes should be used with this approach [7].

Melting temperature represents another crucial consideration, as forward and reverse primers should be designed with similar melting temperatures to ensure comparable annealing efficiency [7]. Standard melting temperature calculations prove challenging for SDM because most online tools cannot accurately account for alterations caused by mismatched nucleotides. Specialized tools such as NEBaseChanger address this limitation by providing annealing temperatures that incorporate adjustments for primer mismatches [7].

For traditional overlapping primer methods, primers should contain the desired mutation in the center, flanked by 12-18 complementary bases on both sides [8] [9]. The introduction or ablation of a restriction site through mutagenesis significantly facilitates subsequent screening for successfully mutated clones [9]. Additionally, primers longer than 40-50 nucleotides should undergo PAGE purification to minimize errors from incomplete synthesis [7].

Technical Optimization Parameters

Several technical parameters require careful optimization to ensure successful mutagenesis outcomes. The use of high-fidelity DNA polymerase with 5'→3' polymerase activity, 3'→5' exonuclease activity (for increased fidelity), and no 5'→3' exonuclease activity is essential to prevent introduction of undesired mutations [9]. The polymerase must produce blunt-ended PCR products, eliminating Taq polymerase from consideration due to its generation of A-overhangs that interfere with plasmid reconstitution [9].

Template quality and concentration significantly impact success rates. High-purity plasmid preparations isolated from methylation-competent bacterial strains (e.g., DH5α, which is dam+) are essential for effective DpnI digestion of the parental template [9]. Smaller plasmids (~3 kb) are generally amplified more efficiently than larger constructs, though plasmids up to ~6 kb can be successfully mutated with adjusted extension times [9]. For GC-rich templates, the addition of DMSO (typically ~3% final concentration) reduces secondary structures and may decrease primer annealing temperatures [9].

Following transformation, screening and validation represent critical quality control steps. If a restriction site was introduced or ablated, bacterial colonies can be screened by restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) analysis [9]. Ultimately, sequencing the mutated region in both directions provides essential confirmation of the desired mutation and absence of unintended modifications [7] [8].

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table summarizes essential reagents and their functions in site-directed mutagenesis workflows:

| Reagent | Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Mutagenic Primers [7] [8] | Introduce specific mutations; anneal to plasmid template | 12-18 complementary bases flanking mutation; similar Tm for forward/reverse; PAGE purification if >40-50 nt |

| High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase [9] | Amplifies plasmid with mutation; maintains sequence accuracy | Must have 5'→3' polymerase activity, 3'→5' exonuclease activity, no 5'→3' exonuclease activity; produces blunt ends |

| DpnI Restriction Enzyme [7] [8] | Selectively digests methylated parental template | Critical for template removal; only cleaves methylated DNA (GATC sequences) |

| Competent E. coli Cells [7] [8] | Propagate mutated plasmid; repair nicked DNA | Chemically competent cells suitable for cloning; transformation efficiency varies by strain and preparation |

| DNA Ligase [7] | Circularizes linear PCR products | Required for back-to-back primer designs; intramolecular ligation recreates circular plasmid |

| Cloning Vector [10] | Replicates mutated DNA independent of host genome | Contains selective marker (antibiotic resistance); allows easy insertion/removal of desired DNA |

Quantitative Analysis of Mutation Effects

Large-scale mutagenesis studies provide invaluable insights into the functional consequences of amino acid substitutions, informing rational protein design strategies. Analysis of 34,373 mutations across 14 proteins revealed significant variation in how different amino acid substitutions impact protein function [11].

Table: Amino Acid Substitution Tolerance and Representation in Protein Mutagenesis

| Amino Acid | Tolerance Ranking | Disruptiveness | Representativeness | Interface Detection Utility |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Methionine | Most tolerated | Low | Moderate | Low |

| Proline | Least tolerated | High | Low | High |

| Histidine | Moderate | Moderate | High (best) | Moderate |

| Asparagine | Moderate | Moderate | High (best) | High |

| Aspartic Acid | Low | High | Low | High (best) |

| Glutamic Acid | Low | High | Low | High (best) |

| Alanine | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate |

This comprehensive analysis demonstrated that methionine substitutions were the most tolerated, while proline substitutions proved most disruptive to protein function [11]. Interestingly, histidine and asparagine substitutions best recapitulated the effects of other substitutions, even when considering wild-type amino acid identity and structural context [11]. For detecting ligand-binding interfaces, highly disruptive substitutions like aspartic acid and glutamic acid showed the greatest discriminatory power [11].

These findings challenge conventional assumptions in protein engineering, particularly the historical preference for alanine scanning mutagenesis. The data suggest that alternative substitution strategies may provide more representative information about position importance or better discrimination of binding interfaces depending on experimental goals [11].

Advanced Applications in Protein Engineering

Multi-Site and Combinatorial Mutagenesis

Advanced SDM applications extend beyond single amino acid substitutions to encompass multi-site mutagenesis and comprehensive analysis of functional residues. Efficient multi-site mutagenesis can be accomplished using assembly methods such as NEBuilder HiFi DNA Assembly, which enables simultaneous introduction of multiple mutations across a protein sequence [5]. This capability proves particularly valuable for exploring synergistic effects between distal residues or reconstructing evolutionary pathways.

Combinatorial approaches have revealed intricate functional connectivity within enzyme active sites. An extensive study of E. coli alkaline phosphatase involving nearly all possible combinations of five active site residues identified three energetically independent but structurally interconnected functional units with distinct cooperative modes [12]. This research demonstrated that despite structural connectivity among all five residues, only subsets directly influenced each other functionally, revealing a complex network of energetic interdependencies that would remain undetected through single-point mutations alone [12].

Integration with Rational Design and High-Throughput Methodologies

Modern protein engineering increasingly combines SDM with computational design and high-throughput screening methodologies. The DiRect method exemplifies this integration, achieving high performance (≥99% substitution efficiency) without recombinant DNA technology [13]. When combined with cell-free protein expression systems, this approach enabled rapid screening of 90 designed mutant proteins within two days, successfully identifying a previously unreported mutant (Q135I) with significantly enhanced thermostability [13].

Such methodologies facilitate the testing of rational design hypotheses while accommodating the exploration of sequence-function relationships beyond purely computational predictions. The continued development of these integrated approaches addresses key bottlenecks in protein engineering pipelines, particularly the reliance on traditional cloning and expression systems that limit throughput and scalability [13].

Detailed Protocol for Site-Directed Mutagenesis

Materials and Reagent Preparation

- Template DNA: High-purity plasmid preparation (0.1-1.0 ng/μl) isolated from a methylation-competent E. coli strain (e.g., DH5α) [9].

- Primers: Forward and reverse primers (10 μM each) containing desired mutation flanked by 12-18 complementary bases [8]. For back-to-back designs, ensure similar melting temperatures (Tm) [7].

- PCR Components: High-fidelity DNA polymerase (e.g., PfuTurbo, Phusion), corresponding reaction buffer, dNTP mix (10 mM each) [8] [9].

- Post-PCR Processing: DpnI restriction enzyme, T4 DNA ligase (for back-to-back designs), ligation buffer [7] [8].

- Transformation: Chemically competent E. coli cells, LB agar plates with appropriate antibiotic, LB broth with antibiotic [8].

Step-by-Step Procedure

PCR Amplification:

- Prepare 50 μl reaction containing: 5-50 ng plasmid template, 10 pmol each primer, 200 μM dNTPs, 1X polymerase buffer, 1-2 units high-fidelity DNA polymerase [8].

- Cycling parameters: Initial denaturation 95°C for 2 minutes; 18-30 cycles of: 95°C for 30 seconds, annealing temperature (Tm -5°C) for 30 seconds, extension at 68°C for 1 minute/kb of plasmid length; final extension 68°C for 5 minutes [8].

- For GC-rich templates, include DMSO to 3% final concentration [9].

Template Removal:

- Add 1 μl DpnI directly to PCR reaction mixture.

- Incubate at 37°C for 1-2 hours to digest methylated parental DNA [8].

Ligation (for back-to-back primer designs):

- Add ligase buffer and T4 DNA ligase to DpnI-treated PCR product.

- Incubate at room temperature for 5 minutes to circularize linear PCR products [7].

Transformation:

Screening and Validation:

- Select 3-5 colonies for screening via colony PCR or restriction analysis if site was introduced/ablated [9].

- Inoculate positive colonies in LB broth with antibiotic and culture overnight.

- Isolate plasmid DNA and sequence the mutated region to confirm desired mutation and absence of secondary mutations [8].

Troubleshooting Common Issues

- Low Efficiency: Optimize template concentration (0.1-1.0 ng/μl), ensure primer melting temperatures are similar, verify DpnI digestion efficiency, and use high-quality competent cells [7] [9].

- No Colonies: Check primer design for complementarity, verify template quality and concentration, ensure antibiotic selection is correct, test competent cell efficiency with control plasmid [8].

- Unintended Mutations: Use high-fidelity polymerase with proofreading activity, minimize PCR cycle number, sequence entire plasmid if critical regions outside target are essential for function [9].

- Primer Duplication: Screen for this artifact by performing restriction digest that excises a short region (<400 bp) proximal to the target site; separated fragments on high-percentage agarose gel (~3%) will show slightly larger band sizes if duplication occurred [9].

Site-directed mutagenesis remains an indispensable technique in the molecular biology toolkit, providing precise control over genetic sequences for protein engineering and functional analysis. The continued refinement of SDM methodologies has expanded their applications from single amino acid substitutions to comprehensive analysis of functional networks and multi-site combinatorial libraries. When strategically employed within rational protein design frameworks, SDM enables critical testing of structure-function hypotheses and provides experimental validation of computational predictions.

The integration of SDM with high-throughput screening technologies and cell-free expression systems represents a promising direction for accelerating protein engineering cycles. Furthermore, large-scale mutational sensitivity data increasingly inform rational design strategies, enabling more intelligent selection of target positions and substitutions. As protein engineering advances toward increasingly ambitious goals, site-directed mutagenesis will continue to provide the essential experimental bridge between digital designs and biological function.

Rational protein design through site-directed mutagenesis is a cornerstone of modern biotechnology and therapeutic development. Its success is fundamentally predicated on two critical pillars: comprehensive protein structural data and detailed functional information. Without these prerequisites, attempts to engineer proteins with enhanced properties, such as improved stability, novel catalytic activity, or regulated allosteric control, revert to random guesswork rather than informed design. This application note details the essential structural and functional data required and provides validated protocols for their implementation within a rational protein engineering framework, empowering researchers to systematically design and characterize novel protein variants.

Essential Structural Data for Informed Mutagenesis

A deep understanding of protein structure is indispensable for predicting the functional consequences of amino acid substitutions. The following structural data types provide complementary insights for guiding mutagenesis strategies.

Table 1: Essential Structural Data for Rational Mutagenesis

| Data Type | Description | Role in Mutagenesis Design | Source/Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| High-Resolution 3D Structure | Atomic-level coordinates from techniques like X-ray crystallography or cryo-EM. | Identifies active sites, binding interfaces, and spatial relationships between residues for targeted mutations. | X-ray, Cryo-EM, NMR [14] |

| Deep Mutational Scanning (DMS) | A comprehensive dataset quantifying the fitness effects of thousands of single-point mutations. | Reveals epistatic interactions between residues to infer structural contacts and functional constraints [14]. | High-throughput selection assays coupled with sequencing [14] |

| Evolutionary Coupling Analysis | Statistical analysis of co-evolving amino acid pairs in multiple sequence alignments. | Identifies residue pairs that are spatially proximal or functionally linked, guiding multipoint mutagenesis [14]. | Bioinformatics tools (e.g., EVcouplings) |

| Predicted Structural Features | Computationally derived data on secondary structure, solvent accessibility, and dynamics. | Pinpoints surface loops and flexible regions that may tolerate insertions or deletions [15]. | AI-based models (e.g., AlphaFold, ESMFold) [16] |

Critical Functional Data for Validating Design Outcomes

Structural data must be complemented by robust functional metrics to validate design hypotheses and quantify the success of mutagenesis experiments.

Table 2: Key Functional Assays for Mutant Characterization

| Functional Property | Key Assays | Measurable Output | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thermostability | Thermal shift assays, Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC). | Melting temperature (Tm), change in free energy of unfolding (ΔΔG). | Engineering robust enzymes for industrial processes [4] [16]. |

| Catalytic Activity | Enzyme-specific kinetic assays (e.g., spectrophotometric, fluorometric). | Michaelis constant (Km), turnover number (kcat), catalytic efficiency (kcat/Km). | Optimizing biocatalysts for enhanced reaction rates or altered substrate specificity. |

| Binding Affinity | Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR), Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC). | Dissociation constant (Kd), enthalpy (ΔH), and entropy (ΔS) of binding. | Developing therapeutic antibodies or modulating protein-protein interactions [14]. |

| Allosteric Regulation | Dose-response or light-response assays in cellular or purified systems. | Half-maximal effective concentration (EC50), dynamic range (fold-induction). | Creating chemogenetic or optogenetic protein switches [15]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: SPRINP Site-Directed Mutagenesis

The Single-Primer Reactions IN Parallel (SPRINP) method is a highly efficient and reliable PCR-based technique for introducing point mutations or small insertions, minimizing the primer-dimer formation common in other protocols [17].

Key Reagents:

- Template DNA: Methylated, dam+ plasmid DNA (e.g., purified from XL1-Blue E. coli).

- Primers: Forward and reverse primers (36-57 nt) containing the desired mutation in the center, designed with high Tm (75–85°C) and GC-clamps.

- Enzyme: High-fidelity DNA polymerase (e.g., Pwo DNA polymerase).

- Restriction Enzyme: DpnI.

Procedure:

- Reaction Setup: Prepare two separate 25 µL PCR reactions.

- Reaction 1: ~500 ng template DNA, 40 pmol forward primer.

- Reaction 2: ~500 ng template DNA, 40 pmol reverse primer.

- Common Mix: 0.2 mM dNTPs, 0.2 mM MgCl₂, 1.25 U Pwo DNA polymerase, 10 mM Tris buffer, pH 7.5.

- PCR Amplification:

- Initial Denaturation: 94°C for 2 min.

- 30 Cycles: Denaturation at 94°C for 40 s, Annealing at 55°C for 40 s, Extension at 72°C (1 min/kb of plasmid size).

- Final Extension: 72°C for 5–10 min.

- Hybridization:

- Combine the two PCR products (total volume 50 µL).

- Denature and reanneal using a slow cooling program: 95°C for 5 min, then step down to 37°C (90°C for 1 min, 80°C for 1 min, 70°C for 30 s, 60°C for 30 s, 50°C for 30 s, 40°C for 30 s, and hold at 37°C).

- Parental Template Digestion: Add 30 units of DpnI directly to the 50 µL hybridized product. Incubate at 37°C overnight to digest the methylated parental DNA strand.

- Transformation: Transform 5–10 µL of the DpnI-treated DNA into competent E. coli cells and plate on selective media for colony isolation.

Protocol: In Silico Prediction of Domain Insertion Sites Using ProDomino

The ProDomino machine learning pipeline rationalizes the engineering of allosteric protein switches by predicting permissive sites for domain insertion, a process that traditionally requires extensive screening [15].

Key Inputs:

- Effector Protein Sequence: The amino acid sequence of the protein to be engineered (the "parent").

- Insert Domain Information: The sequence or structural class of the domain to be inserted (e.g., a light-sensitive LOV domain).

Procedure:

- Data Curation: ProDomino was trained on a semisynthetic dataset derived from naturally occurring intradomain insertion events, encompassing 174,872 sequences with low pairwise identity [15].

- Sequence Encoding: Input the parent protein sequence. ProDomino uses ESM-2-derived protein language model embeddings to convert the sequence into a feature-rich numerical representation [15].

- Model Inference: The processed sequence is analyzed by the ProDomino model, which assigns an "insertion tolerance" score to each residue position in the sequence. High scores indicate sites predicted to tolerate domain insertion without disrupting the structural or functional integrity of the parent protein.

- Output Analysis: The output is a positional score profile. Positions with the highest scores are selected for experimental validation. The model shows no strong bias for surface-exposed loops and can accurately identify permissive sites within secondary structure elements [15].

Workflow Visualization

Diagram 1: Rational protein design workflow.

Diagram 2: SPRINP mutagenesis protocol steps.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Rational Protein Design

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase (e.g., Pwo) | PCR amplification with low error rates for accurate mutant library generation. | SPRINP site-directed mutagenesis protocol [17]. |

| DpnI Restriction Enzyme | Selective digestion of methylated parental plasmid template post-PCR. | Enrichment for newly synthesized mutant strands in SPRINP [17]. |

| QresFEP-2 Software | A hybrid-topology Free Energy Perturbation (FEP) protocol. | Physics-based in silico prediction of mutation effects on protein stability and binding [16]. |

| ProDomino Pipeline | Machine learning model for predicting permissive domain insertion sites. | Rational engineering of allosteric protein switches [15]. |

| Omni-Directional Mutagenesis (ODM) Model | Fine-tuned protein language model (BERT) for generating multipoint mutant libraries. | AI-guided generation of 100,000s of mutant sequences with enhanced properties [4]. |

The intricate relationship between a protein's amino acid sequence, its three-dimensional structure, and its biological function represents a fundamental paradigm in molecular biology. Rational protein design seeks to manipulate this relationship to create novel proteins with enhanced or entirely new functions. Among the most powerful strategies in this endeavor is the use of evolutionary information encapsulated in multiple sequence alignments (MSAs) and consensus design, which leverages nature's vast experimental record to guide engineering efforts. This approach operates on the principle that evolutionary conservation across homologous sequences signals structural and functional importance.

The explosive growth of biological sequence data, coupled with advances in artificial intelligence (AI) and computational modeling, has dramatically expanded the toolkit available to protein engineers. Where earlier methods relied heavily on limited structural information, modern pipelines can now integrate evolutionary insights with deep learning to predict mutation effects and generate novel functional sequences with remarkable efficiency. These approaches have proven particularly valuable for optimizing key protein properties such as thermostability, catalytic efficiency, and expression yield, with applications spanning therapeutic development, industrial biocatalysis, and basic research.

This application note provides a structured framework for implementing MSA and consensus design strategies within rational protein engineering workflows. It details practical protocols, quantitative performance metrics, and computational tools to help researchers harness evolutionary insights for creating improved protein variants.

Theoretical Foundation

The Consensus Design Hypothesis

The core hypothesis underlying consensus design is that, at any given position in a multiple sequence alignment, the most frequently observed amino acid (the consensus residue) contributes more significantly to protein stability than non-conserved alternatives [18]. This premise stems from the evolutionary optimization process, where functionally important residues are maintained across homologous sequences, while less critical positions accumulate neutral mutations. By reconstructing a protein sequence with consensus residues at each position, engineers aim to capture the stabilizing interactions that have been evolutionarily selected throughout the protein family's history.

The theoretical basis for this approach connects evolutionary conservation with protein biophysics. Conserved residues often participate in critical structural roles, such as forming hydrophobic cores, stabilizing secondary structure elements, or maintaining active site architecture. Statistical analyses of consensus design outcomes reveal that approximately 50% of conserved residues are associated with improved stability, while ~10% are stability-neutral, and ~40% can be destabilizing [18]. This distribution underscores the importance of careful MSA construction and analysis rather than blind application of consensus rules.

Diversity of Implementation Strategies

Consensus design principles can be applied through several distinct methodological approaches, each with specific advantages and considerations:

Point Mutagenesis: Single or multiple point mutations are introduced at the most conserved amino acid positions in a target protein. This minimally invasive approach allows researchers to test the individual contribution of specific consensus residues and is particularly valuable when working with proteins that already possess desirable characteristics that should not be disrupted [18].

De Novo Sequence Design: Full-length consensus sequences are constructed entirely from consensus residues, creating novel proteins that represent the evolutionary average of the entire protein family. This approach avoids potential incompatibilities between native and consensus residues but requires recombinant expression and characterization of entirely new protein constructs [18].

Library Enhancement: Consensus residues are used to inform or bias directed evolution libraries, increasing the sampling of functionally relevant sequence space. This hybrid approach combines the broad exploration of random mutagenesis with the focused guidance of evolutionary information [18].

Computational Methods and Protocols

MSA Construction and Curation

The quality of the input MSA directly determines the success of any consensus design project. The following protocol outlines a systematic approach for acquiring and curating homologous sequences:

Table 1: Sequence Database Sources for MSA Construction

| Database | Content Type | Primary Use | Access Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pfam | Curated protein families and HMMs | Domain-specific consensus design | Web interface or HMMER |

| UniProtKB/Swiss-Prot | Manually annotated protein sequences | Full-length protein design | Direct download or API |

| NCBI Protein | Comprehensive protein sequences | Broad homology searches | BLAST/PSI-BLAST |

| Protein Data Bank (PDB) | Experimentally determined structures | Structure-informed design | Direct download |

| Rfam | RNA families | RNA consensus design | Web interface |

Step 1: Sequence Acquisition

- For well-characterized protein families, begin with curated alignment databases such as Pfam or PROSITE which provide pre-computed hidden Markov models (HMMs) and seed alignments [18].

- For novel or poorly characterized targets, use BLAST or PSI-BLAST against UniProtKB or NCBI databases to identify homologous sequences, using an initial E-value threshold of 0.001.

- For remote homology detection, employ iterative search tools like Jackhmmer with bit score thresholds of 0.5-1.0 bits per residue to balance sensitivity and specificity [4].

Step 2: MSA Curation

- Remove redundant sequences at 90-95% identity threshold to reduce taxonomic bias.

- Filter sequences by length to maintain domain architecture integrity.

- Manually inspect and correct alignment errors in functionally important regions.

- For challenging families with low sequence conservation (<30% identity), consider neutral drift experiments to generate functional diversity for alignment [18].

Step 3: Diversity Management

- Assess taxonomic representation to avoid over-representation of specific clades.

- If excessive diversity causes alignment errors, subclassify the MSA into taxonomic subgroups and perform separate consensus calculations [18].

- Balance sequence similarity (for accurate alignment) with diversity (for comprehensive sequence space sampling).

Advanced MSA Post-processing Methods

Recent methodological advances have significantly improved MSA quality through sophisticated post-processing approaches:

Table 2: MSA Post-processing Methods

| Method | Category | Algorithm | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| M-Coffee | Meta-alignment | Consistency library + T-Coffee | DNA/Protein sequences |

| TPMA | Meta-alignment | Two-pointer algorithm + SP scores | Large nucleic acid datasets |

| ReAligner | Realigner (Horizontal) | Single-type partitioning | DNA/RNA local optimization |

| AQUA | Automated pipeline | MUSCLE3 + MAFFT + RASCAL | High-throughput protein design |

Meta-alignment Methods: Tools like M-Coffee integrate multiple independent MSA results generated by different algorithms or parameters to produce a consensus alignment that captures the strengths of each input method. The algorithm constructs a consistency library that weights aligned character pairs according to their agreement across different alignments, then uses the T-Coffee algorithm to generate a final MSA that maximizes global support [19].

Realigner Methods: These tools locally optimize existing alignments without complete realignment. Horizontal partitioning strategies work by iteratively extracting sequences or subgroups and realigning them to the profile of remaining sequences. The single-type partitioning approach extracts one sequence at a time, while tree-dependent partitioning divides the alignment based on phylogenetic relationships before profile-to-profile realignment [19].

Consensus Calculation and Sequence Design

Once a high-quality MSA is obtained, consensus residues can be determined through multiple approaches:

Frequency Threshold Method: The most straightforward approach selects the amino acid with the highest frequency at each position, with optional minimum frequency thresholds (typically 25-40%) to avoid low-confidence calls.

Statistical Methods: More sophisticated approaches use pseudo-counts, sequence weighting, or entropy-based measures to account for sampling bias and phylogenetic relationships within the MSA.

Structure-Informed Filtering: Integrating structural information allows prioritization of consensus mutations in structurally important regions like hydrophobic cores or secondary structure elements, while avoiding surface residues that may be optimized for specific biological interactions.

Integration with AI and Machine Learning

The field of protein engineering has been transformed by the integration of evolutionary information with artificial intelligence methods. Modern pipelines now combine MSAs with deep learning models to generate and screen protein variants with unprecedented efficiency.

Language Model-Based Approaches

Protein language models, particularly those based on the BERT architecture, have demonstrated remarkable capability in capturing evolutionary principles from sequence data alone. The Omni-Directional Multipoint Mutagenesis (ODM) pipeline exemplifies this approach [4]:

Model Architecture and Training:

- Start with a pre-trained protein BERT model (e.g., Mindspore Protein BERT)

- Fine-tune on target-specific homologous sequences obtained from Jackhmmer searches

- Use masked language modeling to learn position-specific amino acid probabilities

- Generate mutant libraries by predicting multiple simultaneous mutations

Weakness Screening (Ws) Metric: Drawing from Barrel Theory, the pipeline identifies "the shortest plank" - the mutation with the lowest predicted probability in each sequence - as the primary limitation on protein activity. Sequences are ranked by their minimal probability value using the formula:

where S represents the sequence set, si is a mutant sequence, and Mi is the predicted probability set for si [4]. This approach enabled identification of protease mutants with 62.5% showing increased thermostability and lysozyme mutants with 50% displaying increased bacteriolytic activity [4].

Structure Prediction with Evolutionary Insights

AlphaFold2 has revolutionized structure prediction by leveraging co-evolutionary signals from MSAs. Recent methods like AF-Cluster extend this capability to predict multiple conformational states by clustering MSAs based on sequence similarity [20]. This approach has successfully predicted fold-switched states in metamorphic proteins and identified point mutations that flip conformational equilibria.

The AF-Cluster protocol involves:

- Generating a deep MSA using ColabFold

- Clustering sequences by edit distance using DBSCAN

- Running separate AlphaFold2 predictions for each cluster

- Analyzing the distribution of structures across clusters

This method has revealed that evolutionary couplings for alternative states can be segregated in sequence space, enabling prediction of both ground and fold-switched states with high confidence [20].

Experimental Validation and Applications

Quantitative Performance Metrics

Consensus design has demonstrated impressive success across diverse protein families, with particularly notable improvements in thermostability:

Table 3: Experimental Performance of Consensus Design

| Protein Target | Property Enhanced | Performance Improvement | Library Size | Success Rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protease ZH1 [4] | Thermostability | Significant increase in Tm | 100,000 variants | 62.5% |

| Lysozyme G732 [4] | Bacteriolytic activity | Increased activity | 100,000 variants | 50.0% |

| Various proteins [18] | Melting temperature | +10°C to +32°C | N/A | ~50% of mutations stabilizing |

| FN3con [18] | Stability | Well-folded, stable | Full consensus | Successful |

| cLRRTM2 [18] | Expression, stability | Well-expressed, stable | Full consensus | Successful |

Case Study: Bacterial Response Regulator Engineering

Evolutionary analysis of ~600,000 bacterial response regulator proteins revealed an unexpected structural relationship between helix-turn-helix (HTH) and winged helix (wH) DNA-binding domains [21]. Through detailed phylogenetic analysis and ancestral sequence reconstruction, researchers identified a covert evolutionary pathway between these two distinct folds.

The experimental workflow included:

- Identification of homologous sequences with different folds (FixJ vs KdpE)

- Statistical validation of homology (e-value 1e-07)

- Phylogenetic analysis of the massive sequence family

- Ancestral sequence reconstruction of key nodes

- Structural characterization of reconstructed ancestors

This study demonstrated how evolutionary insights can reveal unexpected structural plasticity and provide templates for engineering proteins with altered binding specificities [21].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Tools

| Reagent/Tool | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| HMMER Suite | Hidden Markov Model construction | Build custom profiles from seed sequences |

| Jackhmmer | Iterative sequence search | Detects remote homologs; adjust bit score (0.5-1.0 bits/residue) for sensitivity [4] |

| M-Coffee | Meta-alignment | Integrates multiple alignment methods |

| R-scape | Covariation analysis | Statistical validation of RNA structures |

| SISSIz | RNA structure conservation | Z-scores based on shuffled alignments |

| AlphaFold2 | Structure prediction | Requires GPU resources; use ColabFold for accessibility |

| Protein BERT models | Sequence generation | Fine-tune on target-specific families |

| AF-Cluster | Conformational state prediction | DBSCAN clustering of MSA before AF2 prediction [20] |

Workflow Visualization

The integration of multiple sequence alignment analysis with consensus design represents a powerful strategy for rational protein engineering. By leveraging the vast experimental record of natural evolution, researchers can identify stabilizing mutations and functional patterns that would be difficult to predict from first principles alone. The continued development of AI methods, particularly protein language models and advanced structure prediction tools, is further enhancing our ability to extract meaningful signals from evolutionary data.

Successful implementation requires careful attention to MSA construction and curation, as the quality of evolutionary information directly impacts design outcomes. Taxonomic bias, alignment errors, and insufficient diversity can all compromise results. By following the protocols outlined in this application note and utilizing the appropriate computational tools, researchers can systematically harness evolutionary insights to create protein variants with enhanced properties for diverse applications in biotechnology, medicine, and basic research.

In the field of protein engineering, researchers primarily employ two distinct philosophies: rational design and directed evolution (which often utilizes random mutagenesis) [22] [23]. While directed evolution mimics natural selection by randomly generating diversity and selecting for desired functions, rational design takes a more targeted approach based on prior knowledge of protein structure and function [22]. The strategic decision to employ rational design over random mutagenesis is crucial for efficient resource allocation and project success, particularly when specific structural information is available, when engineering precise functional traits, or when high-throughput screening is impractical [24] [23].

Rational design operates on the principle that understanding the sequence-structure-function relationship enables researchers to make precise, predictive changes to a protein's amino acid sequence [22]. This approach contrasts with "irrational" methods that rely on generating large random variant libraries, acknowledging that even with structural data, the effects of multiple mutations on protein function are not easily predictable [23]. This application note provides a structured framework for selecting rational design strategies, complete with comparative analyses, detailed protocols, and practical visualization tools to guide researchers in leveraging rational design's strategic advantages.

Comparative Analysis: Rational Design Versus Alternative Methods

Technical Comparison and Decision Framework

The choice between rational design and random mutagenesis depends on multiple factors, including available structural knowledge, desired property, and resource constraints. The following table summarizes key decision parameters to guide method selection.

Table 1: Strategic Selection Framework for Protein Engineering Approaches

| Decision Parameter | Rational Design | Random Mutagenesis/Directed Evolution |

|---|---|---|

| Structural Knowledge Requirement | Requires high-quality structural data or reliable models [22] | No structural information needed [23] |

| Mutational Precision | Targets specific residues; introduces defined changes [25] | Random mutations across entire sequence [22] |

| Library Size & Screening Burden | Smaller, focused libraries; lower screening burden [24] | Very large libraries; requires high-throughput screening [22] |

| Ideal Application Scope | Engineering specific functions like catalytic activity, binding affinity, or stability when mechanism is understood [22] [24] | Optimizing complex phenotypes or when structure-function relationship is unknown [23] |

| Resource & Time Investment | Higher initial research investment; potentially faster optimization cycles [24] | Lower initial design cost; potentially more iterative testing rounds [22] |

| Risk of Functional Loss | Higher if structural predictions are inaccurate [22] | Lower; typically starts with functional parent sequence [23] |

| Ability to Explore Unknown Sequence Space | Limited to researcher's hypotheses and structural understanding [22] | Broad, unbiased exploration of functional sequence space [23] |

Quantitative Performance Metrics

Modern autonomous enzyme engineering platforms demonstrate the powerful synergy of computational and evolutionary approaches. Recent studies achieving 16- to 90-fold improvements in enzyme activity highlight how machine learning and large language models can guide the design of smart libraries, requiring construction and characterization of fewer than 500 variants for significant optimization [24]. This represents a substantial efficiency improvement over traditional random mutagenesis, which often requires screening thousands to millions of variants [22].

Table 2: Representative Outcomes from Hybrid Engineering Approaches

| Engineering Goal | Enzyme | Fold Improvement | Library Size | Key Method |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Altered Substrate Preference | Arabidopsis thaliana halide methyltransferase (AtHMT) | 90-fold change in preference | <500 variants | AI-guided design [24] |

| Enhanced Activity | Yersinia mollaretii phytase (YmPhytase) | 26-fold at neutral pH | <500 variants | Protein LLM and epistasis model [24] |

| Ethyltransferase Activity | Arabidopsis thaliana halide methyltransferase (AtHMT) | 16-fold improvement | <500 variants | Autonomous engineering platform [24] |

Experimental Protocols for Rational Design

Core Site-Directed Mutagenesis Protocol: DREAM Method

The Designed Restriction Endonuclease-Assisted Mutagenesis (DREAM) method provides an efficient, cost-effective protocol for site-directed mutagenesis that facilitates straightforward mutant screening [25].

Principle: The DNA sequence encoding the target amino acid sequence is reverse-translated using degenerate codons, generating numerous silently mutated sequences containing various restriction endonuclease cleavage sites. A sequence with an appropriate restriction site is selected for mutagenic primer design, enabling easy screening of successful mutants without radioactive hybridization [25].

Materials:

- Template DNA: Double-stranded plasmid containing the target gene [25]

- Primers: Complementary primers containing desired mutation and silent restriction site

- Enzymes: High-fidelity DNA polymerase (e.g., Phusion DNA polymerase), T4 polynucleotide kinase (PNK), T4 DNA ligase, restriction endonuclease for screening [25]

- Supplies: dNTPs, ATP, agarose gel materials, transformation-competent E. coli cells [25]

Procedure:

- Silent Restriction Site Selection: Use computational tools (e.g., WatCut) to identify silent mutations that introduce a restriction site near the target mutation site [25].

- Primer Design: Design inverse PCR primers containing both the desired mutation and the silent restriction site. The primers should be perfectly complementary without overlapping regions when using high-fidelity polymerase [25].

- Inverse PCR: Set up 50μL reaction with:

- 1× HF PCR buffer (Mg²⁺ Plus)

- 200 μmol/L dNTPs

- 200 nmol/L forward and reverse primers

- 1 ng template DNA

- 1 U high-fidelity DNA polymerase

- PCR parameters: 98°C for 30s; 35 cycles of (98°C for 10s, 65°C for 20s, 72°C for 150s); 72°C for 10min [25]

- Product Verification: Separate PCR products on 1% agarose gel electrophoresis and extract correct-sized band [25].

- Phosphorylation: Treat purified PCR product with T4 PNK in 1× T4 PNK buffer with 200 μmol/L ATP at 37°C for 30min [25].

- Ligation: Circularize phosphorylated product using T4 DNA ligase (350 U) at 12°C for 16h [25].

- Transformation: Transform 10μL ligation mixture into competent E. coli cells and plate on selective media [25].

- Screening: Pick random colonies, prepare plasmid DNA, and digest with designed restriction enzyme. Successful mutants will display the expected digestion pattern [25].

- Sequencing: Verify mutation and ensure no secondary mutations in critical regions [25].

Critical Notes:

- Use high-fidelity polymerase (e.g., Phusion with error rate 4.4×10⁻⁷ bp⁻¹) to minimize unwanted mutations [25]

- Method applicable to point mutations, insertions, and deletions [25]

- Sequence broader regions to verify no unintended mutations in regulatory elements [25]

AI-Guided Rational Design Workflow

Modern rational design increasingly incorporates artificial intelligence and machine learning to predict beneficial mutations [24].

Procedure:

- Input Definition: Provide target protein sequence and quantifiable fitness assay [24].

- Variant Prediction: Utilize protein large language models (e.g., ESM-2) and epistasis models (e.g., EVmutation) to generate list of promising variants [24].

- Library Construction: Implement high-fidelity assembly mutagenesis without intermediate sequencing verification [24].

- Automated Characterization: Employ biofoundry platforms for high-throughput transformation, protein expression, and functional assays [24].

- Model Refinement: Use experimental data to retrain machine learning models for subsequent design cycles [24].

Visualization of Strategic Workflows

Protein Engineering Decision Pathway

The following workflow diagram illustrates the strategic decision-making process for selecting between rational design and directed evolution approaches, highlighting key decision points and methodology selection criteria.

Rational Design Experimental Workflow

The DREAM method implementation demonstrates a streamlined protocol for site-directed mutagenesis that facilitates efficient mutant screening through strategic incorporation of restriction sites.

Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of rational design approaches requires specific reagents and tools optimized for precision mutagenesis and analysis.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Rational Design Implementation

| Reagent/Tool | Specifications | Application & Function |

|---|---|---|

| High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase | Phusion DNA polymerase (error rate: 4.4×10⁻⁷ bp⁻¹) [25] | PCR amplification with minimal introduction of unwanted mutations during plasmid amplification for mutagenesis |

| Silent Mutation Design Tool | WatCut web-based software [25] | Identification of silent mutations that introduce restriction enzyme sites for streamlined mutant screening |

| Restriction Endonucleases | Specific to designed silent site (e.g., XhoI) [25] | Rapid screening of successful mutants through diagnostic digest pattern analysis |

| Phosphorylation/Ligation System | T4 Polynucleotide Kinase + T4 DNA Ligase [25] | Phosphorylation and circularization of PCR-amplified plasmid DNA for transformation |

| AI-Guided Design Tools | ESM-2 (protein LLM), EVmutation [24] | Prediction of beneficial mutations based on evolutionary sequence analysis and fitness prediction |

| Automated Biofoundry Platforms | iBioFAB with integrated robotic systems [24] | High-throughput implementation of mutagenesis, transformation, and screening workflows |

Rational design provides strategic advantages over random mutagenesis when structural information is available, when precise control over mutations is required, or when high-throughput screening capabilities are limited. The integration of AI-guided tools with traditional site-directed mutagenesis has created powerful hybrid approaches that maximize the benefits of both rational and evolutionary strategies [24]. The DREAM method exemplifies how thoughtful experimental design can streamline the rational design process, reducing screening burdens while maintaining precision [25].

As computational power and biological understanding advance, rational design continues to evolve from a purely structure-guided approach to an integrated discipline combining physical principles, evolutionary analysis, and machine learning. This progression enables researchers to tackle increasingly complex protein engineering challenges with greater efficiency and success rates, accelerating the development of novel enzymes for therapeutic, industrial, and research applications.

Core Methods and Real-World Applications in Biocatalysis and Therapeutics

Site-directed mutagenesis (SDM) serves as a cornerstone technology in rational protein design, enabling researchers to create specific, targeted changes in double-stranded plasmid DNA. This powerful approach allows scientists to establish direct causal relationships between protein sequence and function by making precise alterations including insertions, deletions, and substitutions [26]. In pharmaceutical and biotechnological applications, quantifying the effects of point mutations is of utmost interest, with reliable computational methods ranging from statistical and AI-based to physics-based approaches accelerating the protein engineering pipeline [16]. The integration of advanced SDM methodologies with high-throughput screening techniques has dramatically accelerated the pace of protein engineering for therapeutic development, enzyme optimization, and fundamental research into protein structure-function relationships.

Within rational protein design frameworks, SDM provides the experimental verification mechanism for hypotheses generated through computational analysis. As researchers aim to elucidate gene functions, engineer proteins with enhanced properties, or develop novel biotherapeutics, the accuracy and efficiency offered by modern SDM protocols become indispensable [26]. These techniques enable the systematic exploration of sequence space in a targeted manner, moving beyond random mutagenesis approaches to make precise alterations that test specific structural or mechanistic hypotheses. The continuing evolution of SDM methods reflects their critical role in bridging computational predictions with experimental validation in the protein engineering workflow.

Established Site-Directed Mutagenesis Methods

QuikChange Method and Its Evolution

The QuikChange methodology represents one of the most widely adopted approaches for site-directed mutagenesis in molecular biology laboratories. The QuikChange II system utilizes PfuUltra high-fidelity (HF) DNA polymerase for mutagenic primer-directed replication of both plasmid strands with the highest fidelity [27]. This method employs a supercoiled double-stranded DNA vector with an insert of interest and two synthetic oligonucleotide primers, both containing the desired mutation and each complementary to opposite strands of the vector.

During thermal cycling, these oligonucleotide primers are extended by DNA polymerase without primer displacement, generating a mutated plasmid containing staggered nicks. A critical selection step follows temperature cycling, where the product is treated with DpnI endonuclease, which specifically digests methylated and hemimethylated DNA (target sequence: 5´-Gm6ATC-3´) [27]. This enzyme efficiently cleaves the parental DNA template (isolated from dam-methylating E. coli strains), while selecting for the newly synthesized mutation-containing DNA. The nicked vector DNA carrying the desired mutations is then transformed into competent cells for propagation.

The QuikChange platform has evolved to address various experimental needs through specialized kits:

- QuikChange II Kit: Optimized for shorter targets (4kb – 8kb) and includes XL1-Blue competent cells

- QuikChange II XL Kit: Designed for longer (8kb – 14kb) or difficult targets and includes XL10-Gold ultracompetent cells

- QuikChange II-E Kit: Formulated for researchers performing mutagenesis via transformation into electroporation-competent cells [27]

Q5 Site-Directed Mutagenesis System

The Q5 Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit developed by New England Biolabs represents an advancement in PCR-based mutagenesis approaches. This system employs a back-to-back primer design strategy rather than the overlapping primers used in traditional methods [26]. This orientation provides significant advantages, including the transformation of non-nicked plasmids and enabling exponential amplification, which generates substantially more of the desired product compared to overlapping primer approaches.

The back-to-back primer design also offers enhanced flexibility for genetic modifications. Because the primers do not overlap each other, deletion sizes are limited only by the plasmid itself, while insertions are constrained primarily by the practical limitations of modern primer synthesis [26]. By strategically splitting insertions between the two primers, researchers can routinely create insertions up to 100 bp in a single reaction step. The method utilizes high-fidelity Q5 polymerase, which ensures exceptional accuracy during amplification, followed by DpnI digestion to eliminate the methylated parental template prior to transformation.

Traditional Laboratory SDM Protocol

For individual research laboratories implementing site-directed mutagenesis, a standardized protocol utilizing commercially available components provides an accessible and cost-effective option. The following protocol uses KOD Xtreme Hot Start DNA Polymerase for high-fidelity PCR amplification followed by DpnI digestion and high-efficiency transformation [28].

Table: Traditional SDM Reaction Setup

| Component | Volume | Final Concentration |

|---|---|---|

| KOD Xtreme Buffer (2X) | 25 μL | 1X |

| Autoclaved Milli-Q water | 10 μL | - |

| dNTPs (2 mM) | 10 μL | 200 μM each |

| Template DNA (25 ng/μL) | 2 μL | ~50 ng |

| Forward primer | 1 μL | 0.2-1.0 μM |

| Reverse primer | 1 μL | 0.2-1.0 μM |

| KOD Xtreme Hot Start DNA Polymerase (1.0 U/μL) | 1 μL | 1.0 U/50 μL reaction |

| Total Volume | 50 μL |

The thermocycling conditions consist of an initial denaturation at 95°C for 2 minutes, followed by 25-35 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 20 seconds, annealing at 60°C for 30 seconds, and extension at 70°C (with time adjusted according to the length of the template DNA, approximately 30 seconds per kb). A final extension at 70°C for 5 minutes completes the amplification [28]. Following PCR amplification, the product undergoes DpnI digestion by adding 5 μL of CutSmart Buffer and 1 μL of DpnI restriction enzyme directly to the PCR product, followed by incubation at 37°C for at least 15 minutes to digest methylated parental DNA.

Transformation is performed using high-efficiency competent cells (such as DH5α), with the entire digestion product added to thawed competent cells on ice. After 10-15 minutes incubation on ice, cells are heat-shocked at 42°C for 40-45 seconds, immediately returned to ice for 2 minutes, then supplemented with SOC media and incubated at 37°C with shaking for 1 hour before plating on selective media [28].

Diagram: Standard SDM Workflow. This flowchart illustrates the fundamental steps in traditional site-directed mutagenesis protocols, from primer annealing to mutant plasmid recovery.

Advanced Methodologies: The DiRect Protocol

DiRect-CF: Integrating SDM with Cell-Free Protein Synthesis

The Dimer-mediated Reconstruction by PCR (DiRect) method represents a significant advancement in site-directed mutagenesis technology, specifically designed to expedite rational design-based protein engineering (RDPE). This innovative approach addresses the major bottleneck in protein engineering workflows - the laborious and time-consuming process of preparing mutant proteins through conventional SDM followed by protein expression [29]. DiRect achieves nearly perfect mutation rates while eliminating the time-consuming steps required by conventional SDM methods, dramatically accelerating the creation of protein variants.

A particularly powerful implementation of this technology is DiRect-CF, which combines the DiRect mutagenesis method with an E. coli cell extract-based cell-free protein synthesis (eCF) system [29]. This integration creates a seamless pipeline from genetic design to protein characterization, bypassing the need for traditional cloning, transformation, and fermentation steps. The cell-free protein synthesis component uses PCR-amplified linearized DNA constructs and cell extracts to express target proteins, omitting multiple time-consuming procedures associated with recombinant DNA technology [29]. This combined approach enables researchers to progress from mutagenic primer design to functional protein analysis in a dramatically compressed timeframe compared to conventional methodologies.

DiRect Experimental Workflow

The DiRect protocol employs three consecutive PCR experiments to achieve high-fidelity mutagenesis: Mutagenesis PCR (MutPCR), Reconstruction PCR with outer primer (RecPCR-out), and Reconstruction PCR with inner primer (RecPCR-in) [29]. In the first stage reaction, both forward and reverse primers for MutPCR are designed with a 5' half comprising a 21-nt complementary sequence containing the mutation site in the middle, and a 3' half consisting of a 19-nt sequence complementary to the template. This design produces a dimer intermediate as the major product, which serves as the template for the subsequent reconstruction PCRs.

The reconstruction phase begins with RecPCR-out, which selectively amplifies the correctly assembled DNA fragment using primers that bind to the outer regions of the expression construct. This is followed by RecPCR-in, which further amplifies the product using primers binding to the inner regions. The final product is exceptionally pure and can be directly used for E. coli cell extract-based CF (eCF) without additional purification or cloning steps [29]. This streamlined workflow has been successfully applied to more than 200,000 construct generations without critical issues, demonstrating its robustness and reliability for high-throughput protein engineering applications.

Table: DiRect-CF Method Advantages

| Feature | Benefit | Application Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Three-step PCR process | Nearly perfect mutation rates | Eliminates need for cloning and sequencing |

| Integration with CFPS | Direct protein expression from PCR products | Reduces timeline from days to hours |

| Minimal background | Negligible original sequence contamination | High-fidelity mutant generation |

| High-throughput compatibility | Scalable for multi-variant studies | Accelerates protein engineering campaigns |

Diagram: DiRect-CF Workflow. This flowchart illustrates the integrated process of DiRect mutagenesis combined with cell-free protein synthesis for rapid protein engineering.

Computational Approaches for Mutation Effect Prediction

QresFEP-2: Hybrid-Topology Free Energy Protocol

In parallel with experimental advances in SDM methodologies, computational approaches for predicting mutational effects have seen significant development. The QresFEP-2 protocol represents a state-of-the-art physics-based method that combines excellent accuracy with high computational efficiency for quantifying the effects of point mutations [16]. This hybrid-topology free energy perturbation (FEP) protocol has been benchmarked on comprehensive protein stability datasets encompassing nearly 600 mutations across 10 protein systems, demonstrating robust performance in predicting mutation-induced thermodynamic changes.

QresFEP-2 employs a novel hybrid topology approach that combines a single-topology representation for conserved backbone atoms with separate topologies for variable side-chain atoms [16]. This methodology overcomes limitations of previous single-topology approaches that required annihilation of both wild-type and mutant side chains to a common alanine intermediate, a process that could introduce artifacts and require extensive simulation steps. The hybrid topology approach implemented in QresFEP-2 avoids transformation of atom types or any bonded parameters, enabling a rigorous and automatable FEP protocol that maintains high computational efficiency while delivering accurate predictions.

Applications in Protein Engineering and Drug Design

The QresFEP-2 protocol demonstrates wide applicability across multiple domains relevant to pharmaceutical development and protein engineering. The method has been validated for assessing the impact of mutations on protein stability through comprehensive domain-wide mutagenesis studies, including a systematic mutation scan of the 56-residue B1 domain of streptococcal protein G (Gβ1) involving over 400 mutations [16]. Additionally, the protocol has proven effective for evaluating site-directed mutagenesis effects on protein-ligand binding, as tested on a GPCR system, and for analyzing protein-protein interactions using the barnase/barstar complex as a model system.

These computational approaches provide valuable triaging tools for rational protein design, helping researchers prioritize which mutations to test experimentally. By accurately predicting the thermodynamic consequences of point mutations before laboratory implementation, these methods significantly reduce the experimental burden and accelerate the protein optimization process. The integration of such computational predictions with advanced SDM methods like DiRect creates a powerful framework for iterative protein engineering, combining in silico design with rapid experimental validation.

Table: Computational Protein Engineering Methods Comparison

| Method | Approach | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| QresFEP-2 | Hybrid-topology free energy perturbation | High accuracy, computational efficiency | Requires protein structure |

| Traditional FEP | Physics-based molecular dynamics | Rigorous thermodynamic calculations | Computationally intensive |

| Machine Learning | AI-based prediction from sequence/structure | Rapid prediction, no simulation required | Generalizability concerns |

| Statistical Potentials | Knowledge-based energy functions | Fast, simple implementation | Limited physical basis |

Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Materials for Site-Directed Mutagenesis

| Reagent/Cell Line | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|