Protein Language Models: How Transformer Architectures Are Revolutionizing Drug Discovery and Bioinformatics

This article provides a comprehensive overview of Protein Language Models (PLMs), deep learning systems based on Transformer architectures that are transforming computational biology and drug discovery.

Protein Language Models: How Transformer Architectures Are Revolutionizing Drug Discovery and Bioinformatics

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of Protein Language Models (PLMs), deep learning systems based on Transformer architectures that are transforming computational biology and drug discovery. By treating protein sequences as a language composed of amino acids, these models learn evolutionary patterns, structural principles, and functional relationships from massive sequence databases. We explore the foundational concepts of PLMs, their diverse architectures and training methodologies, practical applications in target identification and protein design, along with critical troubleshooting and optimization strategies. The article also examines rigorous validation frameworks and comparative performance metrics, offering researchers and drug development professionals essential insights for leveraging these powerful tools to accelerate biomedical innovation.

Decoding the Language of Proteins: From Amino Acid Sequences to Intelligent Models

The analogy of proteins as sentences constructed from amino acid words provides a powerful framework for understanding protein sequence analysis and design. This perspective treats the twenty amino acids as a fundamental alphabet, which combine into "words" or "short constituent sequences" (SCSs) that then assemble into full protein "sentences" with defined structure and function [1]. This linguistic analogy has transitioned from a conceptual metaphor to a practical foundation for modern computational biology, particularly with the advent of transformer-based architectures that directly leverage techniques from natural language processing (NLP) [2] [3]. Research has demonstrated that the rank-frequency distribution of these SCSs in protein sequences exhibits scale-free properties similar to Zipf's law in natural languages, though with distinct characteristics including larger linear ranges and smaller exponents [1]. This distribution suggests that evolutionary pressures on protein sequences may mirror the "principle of least effort" observed in linguistic evolution, balancing the need for mutational parsimony with structural and functional precision [1].

The Grammar of Protein Structure and Function

Hierarchical Language Structure in Molecular Biology

The linguistic analogy extends across multiple biological layers, creating a coherent hierarchy from genetic information to functional molecules. This hierarchical structure enables sophisticated information processing and function execution within biological systems.

Table: The Biological Language Hierarchy

| Linguistic Unit | Biological Equivalent | Functional Role |

|---|---|---|

| Alphabet | Nucleotides (A, C, G, T) | Basic information units |

| Words | Codons / SCSs | Amino acid specification & short functional sequences |

| Sentences | Proteins | Functional molecular entities |

| Paragraphs | Protein complexes & pathways | Higher-order functional assemblies |

DNA serves as the fundamental alphabet with its four nucleotides, while codons of three nucleotides each function as words that specify particular amino acids [4]. These amino acid "words" assemble into protein "sentences" through the cellular translation machinery. Finally, multiple proteins combine to form "paragraphs" representing functional complexes like hemoglobin, which comprises multiple subunits organized to transport oxygen efficiently [4].

Structural Grammar and Connectivity Rules

Protein structures follow grammatical rules that govern how secondary structure elements (SSEs) connect to form functional folds. Research on two-layer αβ sandwiches has revealed that only a limited subset of all theoretically possible connectivities actually occurs in nature [5]. For the 2α-4β arrangement, only 48 out of 23,000 possible connectivities (0.2%) are free from irregular connections like loop crossing, and among these, only 20 have been observed in natural proteins [5]. This demonstrates strong structural "grammar" rules that constrain protein fold space. These rules include preferences against consecutive parallel SSEs, loop crossing, left-handed β-X-β connections, and split β-turns [5]. The observed bias toward specific "super-connectivities" suggests that evolutionary pressure has selected for connectivities that satisfy both structural stability and functional requirements.

Diagram: Structural grammar rules governing protein fold formation. These constraints explain why only a small fraction of theoretically possible connectivities appear in nature.

Transformer Architectures for Protein Language Modeling

Evolution from Linguistic Analysis to Deep Learning

The application of linguistic analysis to proteins has evolved significantly from early statistical approaches to contemporary transformer-based models. Initial work focused on identifying SCSs and analyzing their distribution using principles like Zipf's law [1]. Modern approaches now employ large-scale transformer architectures pretrained on massive protein sequence databases, capturing complex patterns and relationships that enable sophisticated structure and function predictions [2] [3]. The Protein Set Transformer (PST) represents a recent advancement that models entire genomes as sets of proteins, demonstrating protein structural and functional awareness without requiring explicit functional labels during training [3]. This model outperforms homology-based methods for relating viral genomes based on shared protein content, particularly valuable for studying rapidly diverging viral proteins where traditional homology methods falter [3].

Key Architectures and Methodologies

Transformer-based protein language models employ several key architectural innovations adapted from NLP while addressing unique challenges in biological sequences:

- Attention Mechanisms: Self-attention layers enable the model to capture long-range dependencies in protein sequences, analogous to relationships between distant words in sentences [2] [3].

- Permutation-Invariant Set Processing: Models like PST process protein sets without imposing an inherent order, making them suitable for genome-level analysis where gene order may vary [3].

- Multi-scale Modeling: Advanced architectures simultaneously capture amino acid-level details and protein-level features, enabling predictions across structural hierarchies [2].

Table: Quantitative Performance of Protein Language Models

| Model | Training Data | Key Capabilities | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| ESM-2 [3] | 250 million protein sequences | Atomic-level structure prediction | Evolutionary analysis, function prediction |

| Protein Set Transformer [3] | >100,000 viral genomes | Protein-set embedding, functional clustering | Viral genomics, host prediction |

| ProGen [2] | Diverse protein families | De novo protein generation | Protein design, enzyme engineering |

Experimental Protocols and Research Applications

Fold-Switching Protein Design

The linguistic analogy enables sophisticated protein engineering, exemplified by recent work designing fold-switching proteins [6]. This protocol creates sequences compatible with two different native sets of interactions, allowing single amino acid substitutions to trigger profound conformational and functional changes:

- Threading and Alignment: Thread the sequence of a smaller fold (e.g., 3α-helix bundle) through the structure of a larger fold (e.g., α/β-plait) to identify promising alignments that minimize catastrophic interactions [6].

- Computational Design: Use Rosetta-based design to resolve unfavorable interactions in clusters of 4-6 amino acids, employing energy minimization while conserving original amino acids whenever possible [6].

- Stability Optimization: Computationally mutate amino acids at non-overlapping positions to optimize stability in both target folds, followed by energy minimization and evaluation [6].

- Experimental Validation: Express designed proteins in E. coli, purify, and characterize using NMR spectroscopy, circular dichroism, and functional binding assays [6].

This approach has successfully created proteins that switch between three common folds (3α, β-grasp, and α/β-plait) and their associated functions (HSA-binding, IgG-binding, and protease inhibition) [6].

Diagram: Experimental pathway for designing fold-switching proteins. This demonstrates how the protein language can be engineered to create sequences compatible with multiple structures.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Research Reagents for Protein Language Model Applications

| Reagent / Resource | Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| nr-aa Database [1] | Non-redundant protein sequence database | Training data for language models, SCS frequency analysis |

| Rosetta Software Suite [6] | Protein structure prediction and design | Computational design of fold-switching proteins |

| ECOD Database [5] | Evolutionary protein domain classification | Connectivity analysis, fold space enumeration |

| PDB-REPRDB [1] | Representative protein structures | Motif analysis, structural validation |

| NMR Spectroscopy [6] | 3D structure determination | Experimental validation of designed protein structures |

Future Directions and Challenges

The field of protein language modeling faces several important challenges and opportunities. Current limitations include handling the immense diversity of viral proteins, where rapid divergence reduces homology-based signal [3]. Future research directions include developing models that better incorporate structural constraints and physicochemical properties, moving beyond pure sequence-based approaches [2] [6]. The integration of protein language models with experimental validation creates a virtuous cycle where model predictions inform design, and experimental results refine model training [6]. As these models advance, they promise to accelerate drug discovery by enabling more accurate prediction of protein-ligand interactions, functional effects of mutations, and design of novel therapeutic proteins [2] [3]. The fundamental analogy of proteins as sentences will continue to provide a conceptual foundation for these advances, bridging computational innovation with biological understanding.

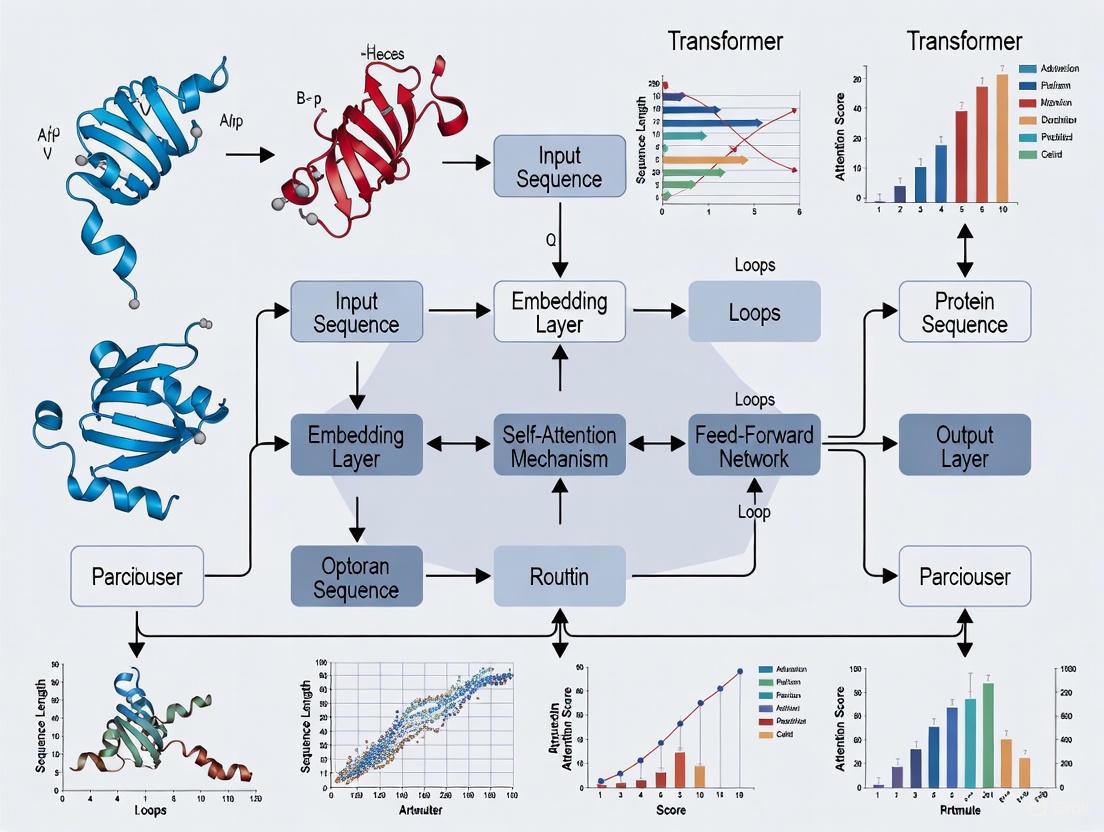

The evolution of transformer architectures represents a pivotal shift in artificial intelligence, with profound implications for computational biology. This progression, from simple word embeddings to the sophisticated self-attention mechanisms that underpin modern protein language models (pLMs), has fundamentally reshaped our ability to decode biological sequences. Within the specific context of protein language models research, understanding this architectural revolution is not merely academic—it provides the foundational knowledge required to engineer next-generation tools for drug discovery, protein design, and functional annotation. This technical guide traces the critical path of this transformation, examining how each architectural breakthrough has directly advanced our capacity to model the complex language of proteins.

The Pre-Transformer Era: Foundations in Sequence Modeling

Before the advent of transformers, sequence modeling in computational biology was dominated by architectures with inherent limitations for capturing long-range dependencies in biological data.

Recurrent Neural Networks and Their Limitations

The earliest approaches to sequence modeling relied on Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs), which process data sequentially, maintaining a hidden state that theoretically carries information from previous time steps. In 1990, the Elman network introduced this concept, using recurrent connections to provide networks with a dynamic memory [7]. Each word in a training set was encoded as a vector through word embedding, creating a numerical representation of sequence data [7]. However, a major shortcoming emerged: when identically spelled words with different meanings appeared in context, the model failed to differentiate between them, highlighting its limited contextual understanding [7].

The Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) network, proposed in 1997 by Hochreiter and Schmidhuber, addressed the vanishing gradient problem through a gating mechanism [8] [7]. This architecture featured a cell state with three specialized gates: forget, input, and output, which controlled information flow, allowing the network to retain important information over extended sequences [7]. While LSTMs became the standard for long sequence modeling until 2017, they still relied on sequential processing, preventing parallelization over all tokens in a sequence [8].

The Attention Mechanism Breakthrough

A critical breakthrough came with the integration of attention mechanisms into sequence-to-sequence (seq2seq) models. The RNN search model introduced attention to seq2seq for machine translation, solving the bottleneck problem of fixed-size output vectors and enabling better handling of long-distance dependencies [8]. This model essentially "emulated searching through a source sentence during decoding a translation" [8].

By 2016, decomposable attention applied a self-attention mechanism to feedforward networks, achieving state-of-the-art results in textual entailment with significantly fewer parameters than LSTMs [8]. This pivotal work suggested that attention without recurrence might be sufficient for complex sequence tasks, planting the seed for the transformer architecture's fundamental premise: "attention is all you need" [8].

Table 1: Evolution of Pre-Transformer Architectures for Sequence Modeling

| Architecture | Key Innovation | Limitations | Biological Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Elman Network (1990) | Recurrent connections for dynamic memory [7] | Unable to disambiguate word meanings; vanishing gradients [7] | Early protein sequence modeling |

| LSTM (1997) | Gating mechanism to preserve long-range dependencies [8] [7] | Sequential processing prevents parallelization; computationally expensive [8] | Protein family prediction; secondary structure prediction |

| Attention-enhanced Seq2Seq (2014-2016) | Focus on relevant parts of input sequence [8] | Still built on recurrent foundations; limited context window [8] | Limited use in structural bioinformatics |

The Transformer Revolution: Core Architecture and Mechanisms

The 2017 publication of "Attention Is All You Need" introduced the transformer architecture, marking a fundamental paradigm shift in sequence modeling that would eventually revolutionize computational biology.

Fundamental Components

The original transformer architecture discarded recurrence and convolutions entirely in favor of a stacked self-attention mechanism [8] [9]. Its key components include:

Self-Attention Mechanism: This allows the model to learn relationships between all elements of a sequence simultaneously, regardless of their positional distance [9]. The core function is computed as Attention(Q,K,V) = softmax(QKᵀ/√dₖ)V, where Q (queries), K (keys), and V (values) are matrices derived from the input [9].

Multi-Head Attention: Instead of performing a single attention function, the transformer uses multiple attention "heads" in parallel, each with learned projections [8] [9]. This allows the model to jointly attend to information from different representation subspaces, capturing diverse linguistic or biological relationships [9]. The outputs are concatenated and projected: MultiHeadAttn(Q,K,V) = [head₁,...,headₕ]Wᴼ where headᵢ = Attention(QWᵢᴼ, KWᵢᴷ, VWᵢⱽ) [9].

Positional Encodings: Since self-attention lacks inherent sequence order awareness, transformers inject positional information using sinusoidal encodings [9]. For each position

posand dimensioni, the encoding is computed as: PE(pos, 2i) = sin(pos/10000^(2i/dmodel)) and PE(pos, 2i+1) = cos(pos/10000^(2i/dmodel)) [9].Feed-Forward Networks: Each transformer block contains a position-wise feed-forward network with two linear transformations and a ReLU activation: FFN(x) = max(0, xW₁ + b₁)W₂ + b₂ [9].

Residual Connections and Layer Normalization: Each sublayer employs residual connections followed by layer normalization to stabilize training and mitigate vanishing gradients [9]. This can be represented as: H' = SelfAttention(X) + X; H = FFN(H') + H' [9].

Evolutionary Improvements to the Original Architecture

Since 2017, several critical refinements have enhanced transformer performance and stability:

Pre-Norm Configuration: Moving layer normalization before the sublayer ("pre-norm") rather than after ("post-norm") improves training stability and gradient flow in very deep networks [10]. Most modern transformer-based architectures (GPT-3, PaLM, LLaMA) now adopt pre-norm by default [10].

Rotary Positional Encodings (RoPE): RoPE encodes relative position information by applying a rotation operation to Query and Key vectors based on their relative positions [10]. This provides smooth relative encoding, multi-scale awareness, and easier extension to long contexts, making it particularly valuable for biological sequences [10].

Mixture of Experts (MoE): MoE layers replace standard feed-forward sublayers with multiple "expert" sub-networks, routing tokens to specialized processing paths [10]. This dramatically increases model capacity without proportionally increasing computational cost—a crucial advancement for large-scale biological models [10].

Transformer Adoption in Protein Language Models

The translation of transformer architectures to biological sequences has created a paradigm shift in computational biology, enabling unprecedented advances in protein structure prediction, function annotation, and design.

Architectural Adaptations for Protein Sequences

Protein language models adapt the core transformer architecture to biological sequences through several key modifications:

Tokenization Strategy: Whereas NLP transformers tokenize text into words or subwords, pLMs tokenize protein sequences into individual amino acids or meaningful k-mers, creating a biological vocabulary of 20 standard amino acids plus special tokens [2] [11].

Pre-training Objectives: pLMs employ self-supervised pre-training using masked language modeling (MLM) or autoregressive objectives [11]. In MLM, random amino acids are masked and predicted from context, forcing the model to learn biochemical principles and evolutionary constraints [11]. Autoregressive approaches predict the next amino acid in sequence, capturing sequential dependencies [11].

Taxonomic and Structural Awareness: Advanced pLMs incorporate structural biases or multiple sequence alignments (MSAs) to enhance predictions, with some models directly integrating structural data during training [3] [12].

Table 2: Key Protein Language Models and Their Transformer Architectures

| Model | Architecture | Parameters | Pre-training Objective | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ESM-2 [11] | Transformer Encoder | 8M to 15B [11] | Masked Language Modeling | Structure prediction, function annotation [13] [11] |

| ProtT5 [11] | Encoder-Decoder (T5) | Up to 3B [11] | Masked Language Modeling | Protein function prediction, embeddings [11] |

| ProGen [11] | Transformer Decoder | Up to 6.4B [11] | Autoregressive | De novo protein design [11] |

| Protein Set Transformer (PST) [3] | Set Transformer | - | Set-based learning | Viral genome classification [3] |

Performance Comparison with Traditional Methods

The adoption of transformer architectures has dramatically improved performance across various protein informatics tasks. Traditional methods based on sequence similarity (e.g., BLAST) or convolutional neural networks are increasingly outperformed by transformer-based approaches [12]. For example, ESM-1b as a coding tool significantly improved the accuracy of protein function prediction tasks [12]. In the Critical Assessment of Protein Function Annotation (CAFA) challenge, methods utilizing pLMs consistently outperform traditional approaches [12].

Experimental Applications and Methodologies

Fine-tuning Strategies for Domain Adaptation

A critical methodology in adapting general pLMs to specialized biological tasks is fine-tuning, particularly for underrepresented protein families. Recent research demonstrates that fine-tuning pre-trained pLMs on viral protein sequences significantly enhances representation quality and downstream task performance [11].

Parameter-Efficient Fine-Tuning (PEFT) methods like Low-Rank Adaptation (LoRA) have proven particularly valuable for large pLMs [11]. LoRA decomposes model weight matrices into smaller, low-rank matrices, dramatically reducing trainable parameters and computational requirements [11]. A typical implementation uses a rank of 8, achieving competitive performance while maintaining computational efficiency [11].

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Transformer-based Protein Modeling

| Reagent/Resource | Type | Function | Example Implementation |

|---|---|---|---|

| ESM-2 Model Weights [11] | Pre-trained model | Provides foundational protein representations | ESM-2-3B, ESM-2-15B variants [11] |

| LoRA (Low-Rank Adaptation) [11] | Fine-tuning method | Efficient parameter adaptation for specialized tasks | Rank=8 adaptation for viral proteins [11] |

| UniProt Database [11] | Protein sequence database | Training and evaluation dataset | >240 million protein sequences [12] |

| Annotated Protein Benchmark Sets [12] | Evaluation dataset | Performance validation | Swiss-Prot, CAFA challenges [12] |

| Sparse Autoencoders (SAEs) [13] | Interpretability tool | Feature discovery in latent representations | InterPLM, InterProt frameworks [13] |

Case Study: Fine-tuning for Viral Protein Analysis

Experimental Protocol: A 2025 study systematically evaluated LoRA fine-tuning with three representation learning approaches—masked language modeling, classification, and contrastive learning—on viral protein benchmarks [11].

Methodology:

- Model Selection: Pre-trained ESM-2-3B, ProtT5-XL, and ProGen2-Large models were used as base architectures [11].

- Fine-tuning: LoRA was applied with diverse learning objectives to adapt models to viral protein sequences [11].

- Evaluation: Embedding quality was assessed on downstream tasks including remote homology detection, function prediction, and structural property inference [11].

Results: The study demonstrated that LoRA fine-tuning with virus-domain specific data consistently enhanced downstream bioinformatics performance across all model architectures, validating the importance of domain adaptation for specialized biological applications [11].

Future Directions and Research Opportunities

The evolution of transformer architectures for biological sequences continues to present numerous research opportunities:

Multi-modal Integration: Future architectures may seamlessly integrate sequence, structure, and functional data within unified transformer frameworks, potentially using cross-attention mechanisms between modalities [2] [12].

Interpretability and Biological Insight: Techniques like sparse autoencoders (SAEs) are being applied to pLMs to extract interpretable features corresponding to biologically meaningful concepts [13]. For example, SAE analysis has revealed features activating on specific structural motifs (α-helices, β-sheets) and functional domains [13].

Long-Range Dependency Modeling: Biological sequences often contain long-range interactions, particularly in non-coding DNA and protein allostery. Advanced positional encoding schemes like RoPE and hierarchical attention mechanisms offer promising avenues for capturing these relationships [10].

Scalability and Efficiency: As biological datasets grow exponentially, developing more efficient transformer variants through methods like mixture-of-experts and linear attention mechanisms will be crucial for maintaining tractability [10].

The historical evolution from early embeddings to modern transformer architectures has positioned computational biology at the threshold of unprecedented discovery. By understanding this architectural progression and its biological applications, researchers can better leverage these powerful tools to unravel the complexity of protein sequences and accelerate therapeutic development.

Transformer architectures have become the foundational framework for natural language processing (NLP) and are now revolutionizing computational biology, particularly in the analysis and design of protein sequences [2]. The core architectural paradigms—encoder-only, decoder-only, and encoder-decoder models—each provide distinct advantages for specific tasks in protein research and drug development. Understanding these architectures is essential for researchers and scientists selecting appropriate models for tasks ranging from protein function prediction to de novo protein design.

This technical guide provides an in-depth analysis of these three transformer architectures, with specific emphasis on their applications in protein language models. We examine their fundamental operating principles, training methodologies, and quantitative performance characteristics to equip researchers with the knowledge needed to advance computational drug discovery and protein engineering.

Fundamental Architecture Components

All transformer architectures utilize a core set of components that enable their sophisticated sequence processing capabilities.

Self-Attention Mechanism

The self-attention mechanism forms the core of all transformer architectures, allowing the model to weigh the importance of different elements in a sequence when processing each element [14]. The operation transforms token representations by computing attention scores between all token pairs in a sequence. For an input sequence represented as a matrix ( X ) of dimension ( [B, T, d] ) (where ( B ) is batch size, ( T ) is sequence length, and ( d ) is embedding dimension), the model first projects the input into queries (Q), keys (K), and values (V) using learned linear transformations [14]:

[ \text{Attention}(Q, K, V) = \text{softmax}\left(\frac{QK^T}{\sqrt{d_k}}\right)V ]

The scaling factor ( \sqrt{d_k} ) improves training stability by preventing extremely small gradients [14]. Multi-head attention extends this mechanism by performing multiple attention operations in parallel, each with separate projection matrices, enabling the model to jointly attend to information from different representation subspaces [14] [8].

Positional Encoding

Unlike recurrent networks that inherently capture sequence order, transformers require explicit positional encodings to incorporate information about token positions [15]. These encodings, either fixed or learned, are added to the input embeddings before processing. For long sequences, axial positional encodings factorize the large positional encoding matrix into smaller matrices to conserve memory [16].

Encoder-Only Architecture

Architectural Principles

Encoder-only models utilize solely the encoder stack of the original transformer architecture [17] [16]. These models employ bidirectional self-attention, allowing each token in the input sequence to attend to all other tokens in both directions [17] [16]. This comprehensive contextual understanding makes encoder models particularly suited for analysis tasks requiring deep comprehension of the entire input.

The training of encoder models typically involves denoising objectives where the model learns to reconstruct corrupted input sequences [16]. For protein sequences, this approach enables the model to learn robust representations of protein structure and function.

Training Methodology

Encoder-only models are predominantly trained using Masked Language Modeling (MLM) [17]. In this approach, random tokens in the input sequence are replaced with a special [MASK] token, and the model must predict the original tokens based on the bidirectional context [17]. For BERT-based protein models, this typically involves masking 15% of amino acids in the protein sequence [17].

Some encoder architectures incorporate Next Sentence Prediction (NSP) during pre-training, where the model determines whether two sequences follow each other in the original corpus [17]. For protein models, this can be adapted to predict functional relationships between protein domains.

Key Protein Model Implementations

Table 1: Encoder-Only Protein Language Models

| Model Name | Key Features | Protein Applications |

|---|---|---|

| BERT-based Protein Models | Bidirectional attention, MLM pre-training | Protein function prediction, functional residue identification [2] |

| ESM (Evolutionary Scale Modeling) | Trained on evolutionary sequences, structural awareness | Protein structure prediction, functional site identification [2] [3] |

| RoBERTa-based Protein Models | Optimized BERT pre-training without NSP | Protein property prediction, variant effect analysis [15] |

Research Applications in Protein Science

Encoder-only models excel in protein classification tasks such as enzyme commission number prediction, Gene Ontology (GO) term annotation, and protein family classification [2] [3]. Their bidirectional nature enables accurate prediction of binding sites and functional residues by integrating contextual information from the entire protein sequence [2].

These models have demonstrated exceptional capability in protein variant effect prediction, where they assess how amino acid substitutions affect protein function and stability [2]. The embeddings generated by encoder models serve as rich feature representations for downstream predictive tasks in computational drug discovery.

Decoder-Only Architecture

Architectural Principles

Decoder-only models utilize exclusively the decoder component of the original transformer [14] [16]. These models employ causal (masked) self-attention, which restricts each token to attending only to previous tokens in the sequence [14]. This autoregressive property makes decoder models naturally suited for sequence generation tasks.

The training objective for decoder models is autoregressive language modeling, where the model predicts each token in the sequence based on preceding tokens [16]. For protein sequences, this enables the generation of novel protein sequences with desired properties.

Causal Self-Attention Implementation

Causal self-attention is implemented using a masking matrix that sets attention scores for future tokens to negative infinity before applying the softmax operation [14]. This ensures that during training, the model cannot "cheat" by looking ahead in the sequence. The implementation typically uses a lower-triangular mask matrix:

Key Protein Model Implementations

Table 2: Decoder-Only Protein Language Models

| Model Name | Key Features | Protein Applications |

|---|---|---|

| GPT-based Protein Models | Autoregressive generation, unidirectional context | De novo protein design, sequence optimization [18] |

| Protein Generator Models | Specialized for biological sequences, conditioned generation | Functional protein design, property-guided generation [2] |

| Large Language Models (LLMs) | Scaled to billions of parameters, instruction fine-tuning | Protein function description, research hypothesis generation [16] |

Research Applications in Protein Science

Decoder-only architectures enable autoregressive protein generation, allowing researchers to design novel protein sequences with specified structural or functional characteristics [2] [18]. These models can generate protein variants optimized for stability, expression, or binding affinity.

In protein sequence completion, decoder models can predict missing segments of partial protein sequences, useful for designing linkers or terminal extensions [18]. Their next-token prediction capability also facilitates protein sequence optimization through iterative refinement.

Encoder-Decoder Architecture

Architectural Principles

Encoder-decoder models utilize both components of the original transformer architecture [19] [15]. The encoder processes the input sequence with bidirectional attention, creating a comprehensive contextual representation [15]. The decoder then generates the output sequence autoregressively while attending to both previous decoder states and the full encoder output through cross-attention mechanisms [15].

This architecture is particularly suited for sequence-to-sequence tasks where the output significantly differs in structure or length from the input [15]. For protein research, this enables complex transformations between sequence representations.

Training Methodology

Encoder-decoder models are often trained using denoising or reconstruction objectives [16]. For example, the T5 model uses span corruption, where random contiguous spans of tokens are replaced with a single sentinel token, and the decoder must reconstruct the original tokens [16].

In protein applications, training objectives can include sequence translation tasks, such as generating protein sequences from structural descriptors or converting between different representations of protein information.

Research Applications in Protein Science

Encoder-decoder models facilitate protein sequence-to-function prediction, where the encoder processes the protein sequence and the decoder generates functional annotations or properties [2]. These models excel at multi-modal protein tasks, such as generating protein sequences from textual descriptions of desired functions [2].

These architectures also enable protein sequence transformation, such as optimizing wild-type sequences for enhanced properties or generating functional variants within structural constraints [15]. The bidirectional encoding coupled with autoregressive decoding provides the necessary framework for complex protein engineering tasks.

Comparative Analysis of Architectures

Quantitative Performance Metrics

Table 3: Architecture Comparison for Protein Tasks

| Architecture | Sequence Length Handling | Training Objective | Optimal Protein Tasks | Computational Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Encoder-Only | Quadratic complexity, full context | Masked Language Modeling (MLM) | Function prediction, variant effect, structure prediction [2] [16] | High memory usage for long sequences |

| Decoder-Only | Quadratic complexity, causal context | Autoregressive Language Modeling | De novo design, sequence completion, property optimization [18] [16] | Efficient during inference (sequential) |

| Encoder-Decoder | Quadratic for both input and output | Sequence-to-Sequence Learning | Sequence optimization, function translation, multi-modal tasks [15] [16] | Highest memory and computation requirements |

Architectural Selection Framework

Experimental Protocols for Protein Language Models

Standardized Evaluation Framework

To ensure fair comparison across architectural paradigms, researchers should implement standardized evaluation protocols when benchmarking protein language models:

Task-Specific Benchmarking:

- Function Prediction: Evaluate using Gene Ontology (GO) term prediction accuracy across biological process, molecular function, and cellular component categories [2]

- Structure Prediction: Assess using TM-score and RMSD between predicted and experimental structures [3]

- Variant Effect Prediction: Measure using ROC-AUC for classifying pathogenic versus benign variants [2]

Training Methodology:

- Implement transfer learning with pre-trained weights followed by task-specific fine-tuning

- Use k-fold cross-validation with stratified splits based on protein family classification

- Apply early stopping with patience of 10-20 epochs based on validation performance

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Materials for Protein Language Model Experiments

| Reagent/Material | Function | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|

| Protein Sequence Databases | Training data source | UniProt, Pfam, CATH for diverse protein families [2] |

| Structural Datasets | Evaluation and multi-modal training | Protein Data Bank (PDB), AlphaFold DB [3] |

| Functional Annotation Sources | Supervision for fine-tuning | Gene Ontology (GO), Enzyme Commission (EC) numbers [2] |

| Variant Effect Databases | Benchmarking pathogenic prediction | ClinVar, gnomAD, protein-specific variant databases [2] |

| Computation Frameworks | Model implementation and training | PyTorch, TensorFlow, JAX with transformer libraries [14] |

| Specialized Attention Implementations | Long sequence handling | Longformer, Reformer, or custom sparse attention for genomes [16] |

Future Directions in Protein Transformer Architectures

The field of protein language models is rapidly evolving, with several promising research directions emerging. Hybrid architectures that combine elements from multiple paradigms show potential for addressing complex protein design challenges [2]. Sparse attention mechanisms enable processing of extremely long sequences, such as complete viral genomes or multi-protein complexes [16].

Multimodal protein models that integrate sequence, structure, and functional data within unified architectures represent the next frontier in computational protein science [2] [3]. These advancements will further accelerate drug discovery and protein engineering applications.

Encoder-only, decoder-only, and encoder-decoder architectures each offer distinct advantages for protein research applications. Encoder-only models provide comprehensive understanding for prediction tasks, decoder-only models enable creative generation of novel sequences, and encoder-decoder architectures facilitate complex transformations between protein representations. As protein language models continue to evolve, understanding these fundamental architectural paradigms will remain essential for researchers developing next-generation computational tools for drug development and protein engineering.

The emergence of protein language models (PLMs) represents a paradigm shift in bioinformatics, drawing direct inspiration from the transformative success of large language models in natural language processing (NLP) [20] [21]. The conceptual similarity between protein sequences—linear chains of 20 amino acids—and natural language—strings of words—has enabled the application of powerful transformer architectures to biological data [20]. These models leverage self-supervised pre-training on massive datasets of protein sequences to learn fundamental principles of protein structure and function, revolutionizing tasks ranging from protein design to drug discovery [12] [21].

Within this context, the choice of pre-training objective becomes paramount in determining a model's capabilities and limitations. Two dominant paradigms have emerged: Masked Language Modeling (MLM) and Autoregressive (AR) Prediction [22] [20]. These objectives shape how a model learns from data and ultimately what biological insights it can provide. MLM, a bidirectional approach, allows the model to leverage contextual information from both sides of a masked token, making it particularly powerful for understanding protein semantics and function [20]. In contrast, AR Prediction, a unidirectional approach, trains models to predict the next token in a sequence, making it exceptionally well-suited for generative tasks such as de novo protein design [20] [21]. This technical guide provides an in-depth analysis of these two core pre-training objectives, their architectural implementations, their respective strengths and limitations, and the emerging hybrid approaches that seek to harness the benefits of both paradigms within the critical domain of protein science.

Masked Language Modeling (MLM)

Core Principles and Theoretical Foundations

Masked Language Modeling (MLM) is a self-supervised pre-training objective that trains a model to reconstruct randomly masked tokens within an input sequence based on their bidirectional context. Originally popularized by BERT in NLP [20], its application to protein sequences involves treating amino acids as tokens. During pre-training, a fraction of the input amino acids in a protein sequence (e.g., 15%) are randomly replaced with a special [MASK] token. The model is then trained to predict the original identities of these masked tokens using information from all unmasked positions in the sequence [20].

The formal objective is to minimize the negative log-likelihood of the correct tokens given the masked input. For a protein sequence ( x = (x1, x2, ..., xL) ) of length ( L ), a random subset of indices ( m \subset {1, ..., L} ) is selected for masking. The model learns to maximize ( \log p(xm | x{\setminus m}) ), where ( x{\setminus m} ) represents the sequence with the tokens at positions in ( m ) masked [22] [20]. This bidirectional understanding is particularly valuable for proteins, where the function of an amino acid can depend on residues that are both upstream and downstream in the sequence, or even far apart in the linear sequence but close in the three-dimensional structure.

Architectural Implementation in Proteins

MLM is typically implemented using encoder-only Transformer architectures [20]. The encoder uses bidirectional self-attention, allowing each position in the sequence to attend to all other positions. This is crucial for capturing the complex, long-range dependencies that characterize protein folding and function.

Table 1: Representative MLM-based Protein Language Models

| Model Name | Architecture | Key Features | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| ESM (Evolutionary Scale Modeling) [20] | Transformer Encoder | Trained on millions of diverse protein sequences from UniRef. | Protein function prediction, structure prediction. |

| ProtTrans [20] | Ensemble of BERT-style models | Includes models like ProtBERT, ProtALBERT, trained on UniRef and BFD. | Learning general protein representations for downstream tasks. |

| ProteinBERT [20] | Transformer Encoder with Global Attention | Incorporates a global attention mechanism and multi-task learning. | Protein function prediction with Gene Ontology terms. |

| PMLM [20] | Transformer Encoder with Pairwise MLM | Captures co-evolutionary signals without multiple sequence alignments (MSA). | Inferring residue-residue interactions. |

Experimental Protocols and Evaluation

A standard protocol for pre-training a PLM with MLM involves several key steps. First, a large-scale dataset of protein sequences (e.g., UniRef) is compiled [20] [21]. During training, for each sequence in a batch, 15% of amino acid tokens are selected at random. Of these, 80% are replaced with the [MASK] token, 10% are replaced with a random amino acid token, and 10% are left unchanged. This stochasticity helps make the model more robust [20].

The model's hidden states corresponding to the masked positions are passed through a linear classification head to predict the probability distribution over the 20 amino acids. The loss is computed using cross-entropy between the predicted distribution and the true amino acid identity.

The performance of MLM-pre-trained models is evaluated through downstream tasks. A common benchmark is protein function prediction, where the model's learned representations (e.g., the embedding of the [CLS] token or the mean of all residue embeddings) are used as features to train a classifier to predict Gene Ontology (GO) terms [12] [20]. Another critical evaluation is secondary or tertiary structure prediction, testing how well the learned embeddings capture structural information. For example, the ESM model family has demonstrated that representations learned purely from sequence via MLM can be fine-tuned to predict 3D structure with high accuracy, rivaling methods that rely on computationally intensive multiple sequence alignments [20].

Diagram 1: MLM pre-training workflow. Tokens are masked and the model learns from bidirectional context.

Autoregressive (AR) Prediction

Core Principles and Theoretical Foundations

Autoregressive (AR) Prediction is a generative pre-training objective where a model is trained to predict the next token in a sequence given all preceding tokens. This is a unidirectional approach, fundamentally different from the bidirectional nature of MLM. For a protein sequence ( x = (x1, x2, ..., xL) ), the AR model factorizes the joint probability of the sequence as a product of conditional probabilities: ( p(x) = \prod{i=1}^{L} p(xi | x{

This objective trains the model to capture the natural sequential order and dependencies within the data. In the context of proteins, this sequential generation mirrors the biological process of protein synthesis, where the polypeptide chain is assembled from the N-terminus to the C-terminus. AR models excel at generating novel, coherent, and functionally viable protein sequences by iteratively sampling the next most probable amino acid [21].

Architectural Implementation in Proteins

AR Prediction is implemented using decoder-only Transformer architectures [20]. A critical component of this architecture is the causal mask, which ensures that the self-attention mechanism for a given token can only attend to previous tokens in the sequence, preventing information leakage from the future. This makes the model inherently generative.

Table 2: Representative AR-based Protein Language Models

| Model Name | Architecture | Key Features | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| ProGen [21] | Transformer Decoder | Conditionally generates protein sequences based on property tags (e.g., family, function). | De novo protein design. |

| ProtGPT2 [21] | Transformer Decoder (GPT-2 style) | Trained on the UniRef50 dataset, generates novel protein sequences that are natural-like. | Generating diverse, functional protein sequences. |

| ProteinLM [20] | Transformer Decoder | An early exploration of AR modeling for proteins. | Protein sequence generation and representation learning. |

A key advantage of AR models is their inference efficiency. They can leverage KV (Key-Value) caching during generation, where the key-value pairs for previously generated tokens are stored and reused, significantly reducing computational overhead for each subsequent generation step [22]. This makes them highly scalable for generating long protein sequences.

Experimental Protocols and Evaluation

Pre-training a protein AR model involves presenting the model with a protein sequence and having it predict the next amino acid for every position in the sequence. The standard loss function is the cross-entropy loss between the predicted probability distribution and the actual next token across the entire sequence.

Evaluating AR models for proteins often focuses on generation quality and diversity. Key metrics include:

- Fluency and Naturalness: Measured by the perplexity of the generated sequences against a held-out test set of natural proteins. Lower perplexity indicates the model has learned the statistical regularities of natural protein sequences.

- Structural Plausibility: Using tools like AlphaFold2 to predict the 3D structure of generated sequences and assessing if they fold into stable, protein-like structures [21].

- Functional Efficacy: For models conditioned on specific functions, the evaluation involves wet-lab experiments to verify that the generated proteins exhibit the desired activity (e.g., binding affinity, enzymatic activity) [21]. Studies have shown that AR models like ProGen can generate functional enzymes that are experimentally validated.

Diagram 2: Autoregressive generation. The model iteratively predicts the next token to build a full sequence.

Comparative Analysis and Hybrid Approaches

Trade-offs: MLM vs. AR Prediction

The choice between MLM and AR objectives involves fundamental trade-offs that impact model capabilities, training efficiency, and applicability to downstream tasks in protein research.

Table 3: Comparative Analysis of MLM and AR Pre-training Objectives

| Aspect | Masked Language Modeling (MLM) | Autoregressive (AR) Prediction |

|---|---|---|

| Context Usage | Bidirectional; uses full context around a masked token. | Unidirectional; uses only leftward (preceding) context. |

| Primary Strength | Superior for understanding protein semantics, function prediction, and extracting rich, contextual representations. | Superior for generative tasks, de novo protein design, and sequence completion. |

| Training Complexity | Higher complexity as it learns from an exponentially large number of masking patterns [23]. | Lower complexity, focused on a single, natural sequential order. |

| Inference Flexibility | High flexibility at inference; can be adapted to decode tokens in various orders, but standard inference is non-generative [23]. | Fixed left-to-right order during standard generation. |

| Inference Efficiency | Less efficient for generation; no KV caching in standard encoder models. | Highly efficient for generation; supports KV caching for faster sequential decoding [22]. |

| Best-Suited Protein Tasks | Protein function prediction, stability prediction, variant effect analysis, structure prediction. | De novo protein design, sequence optimization, generating protein families. |

As shown in the table, neither objective is universally superior. MLM's bidirectional context is powerful for discriminative and analytical tasks, while AR's sequential nature is ideal for creation and generation. A critical insight from recent research is that the "worst-case" training subproblems for MDMs (a close relative of MLM) can be computationally intractable, but this can be mitigated at inference time through adaptive strategies that choose a favorable token decoding order [23].

Emerging Hybrid Architectures

To harness the complementary strengths of both MLM and AR objectives, researchers have developed several hybrid approaches.

Mask-Enhanced Autoregressive Prediction (MEAP) [24] is a training paradigm that seamlessly integrates MLM into the standard next-token prediction. In MEAP, a small fraction of input tokens are randomly masked, and the model is then tasked with performing standard AR prediction on this partially masked sequence using a decoder-only Transformer. This forces the model to rely more heavily on the remaining non-masked tokens, improving its in-context retrieval capabilities and focus on task-relevant signals without adding computational overhead during inference. This method has been shown to substantially improve performance on tasks requiring key information retrieval from long contexts.

MARIA (Masked and Autoregressive Infilling Architecture) [22] is another hybrid model designed to give AR models the capability of masked infilling—predicting masked tokens using both past and future context. MARIA combines a pre-trained MLM and a pre-trained AR model by training a linear decoder on their concatenated hidden states. This minimal modification allows the model to perform state-of-the-art infilling while retaining the AR model's advantages of scalable training and efficient KV-cached inference.

These hybrid approaches are particularly promising for protein engineering, where tasks often require both a deep, bidirectional understanding of protein function (MLM's strength) and the ability to generate novel, plausible sequences (AR's strength).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Resources for PLM Research and Application

| Resource Name | Type | Description and Function |

|---|---|---|

| UniProt Knowledgebase [12] [21] | Protein Database | A comprehensive, high-quality database of protein sequence and functional information. Serves as the primary pre-training data source for many PLMs. |

| Protein Data Bank (PDB) [12] [21] | Structure Database | A repository for 3D structural data of proteins and nucleic acids. Used for training structure prediction models and validating generated protein structures. |

| ESM Model Family [20] | Pre-trained Model | A suite of large-scale MLM-based protein language models (e.g., ESM-2, ESM-3) from Meta. Used for feature extraction, structure prediction, and function annotation. |

| AlphaFold2 [12] [21] | Prediction Tool | A revolutionary deep learning system for highly accurate protein structure prediction from sequence. Crucial for validating the structural plausibility of designed proteins. |

| ProGen, ProtGPT2 [21] | Pre-trained Model | State-of-the-art AR models for de novo protein design. Used to generate novel, functional protein sequences conditioned on desired properties. |

| Hugging Face Transformers | Software Library | An open-source library providing thousands of pre-trained models. Hosts many popular PLMs, making them easily accessible for fine-tuning and inference. |

The revolutionary progress in protein language models (pLMs) based on Transformer architectures is fundamentally underpinned by the large-scale, high-quality protein sequence databases used for their pre-training. These models learn the complex linguistic patterns of protein sequences—where amino acids serve as words and entire proteins as sentences—to make groundbreaking predictions about protein structure, function, and design. The quality, diversity, and scale of the training data directly determine the model's performance and generalizability. Among the plethora of available resources, three databases stand out as foundational for training state-of-the-art pLMs: UniRef, Swiss-Prot, and the Big Fantastic Database (BFD). This technical guide provides an in-depth analysis of these core resources, detailing their structures, applications in model training, and integration into experimental protocols for protein research and drug development.

Table 1: Core Protein Databases for pLM Training

| Database | Clustering Identity | Key Characteristics | Primary Application in pLMs |

|---|---|---|---|

| UniRef | 100% (UniRef100), 90% (UniRef90), 50% (UniRef50) | Non-redundant clustered sets of sequences from UniProtKB and UniParc [25] | Reducing sequence redundancy; efficient training on sequence space [26] |

| Swiss-Prot (UniProtKB/Swiss-Prot) | Not Applicable | Expertly reviewed, manually annotated entries with high-quality functional data [27] | Fine-tuning for function prediction; high-confidence benchmark datasets [28] [26] |

| BFD (Big Fantastic Database) | Not Explicitly Stated | Large-scale metagenomic sequence database; often used with HH-suite tools [29] | Generating deep Multiple Sequence Alignments (MSAs); enriching evolutionary signals [29] |

Database Architectures and Technical Specifications

UniRef: A Non-Redundant Sequence Space

The UniProt Reference Clusters (UniRef) databases provide clustered sets of protein sequences to minimize redundancy and accelerate sequence similarity searches [25]. UniRef operates at three primary levels of sequence identity, each serving distinct purposes in large-scale computational analyses. UniRef100 clusters sequences that are 100% identical, providing a complete non-redundant set while preserving all annotation data from individual members. UniRef90 is derived from UniRef100 by clustering sequences at the 90% identity threshold, and UniRef50 further clusters sequences at the 50% identity level, offering a broad overview of sequence diversity [25]. For pLM training, these clusters are instrumental in creating balanced datasets that adequately represent the protein sequence universe without computational overhead from highly similar sequences.

Swiss-Prot: The Gold Standard for Manual Annotation

Swiss-Prot, the expertly reviewed section of the UniProt Knowledgebase (UniProtKB), represents the gold standard for protein annotation, with each record containing a summary of experimentally verified or computationally predicted functional information added and evaluated by an expert biocurator [27]. Unlike its computationally annotated TrEMBL counterpart, Swiss-Prot entries feature extensive information on protein function, domain structure, post-translational modifications, and validated variants. This high-quality, trustworthy data is particularly valuable for supervised fine-tuning of pLMs on specific prediction tasks such as enzyme classification, metal ion binding site identification, and subcellular localization. The Gene Ontology (GO) annotations, Rhea biochemical reactions, and disease associations in Swiss-Prot provide structured vocabularies that pLMs can learn to associate with sequence patterns [27].

BFD: Metagenomic Diversity for Evolutionary Signals

The Big Fantastic Database (BFD) is a large-scale metagenomic protein sequence database frequently used in conjunction with HH-suite for sensitive sequence searches and profile construction [29]. While less documented in terms of its internal structure compared to UniProt resources, its value in pLM research comes from its extensive coverage of metagenomic sequences, which provides a vast source of evolutionary information. This diversity is particularly beneficial for constructing deep Multiple Sequence Alignments (MSAs), which are crucial for methods like AlphaFold2 and MSA-Transformer that leverage co-evolutionary signals to infer structural contacts [29]. The BFD's inclusion of environmental sequences expands the known protein sequence space beyond traditionally studied organisms, allowing pLMs to capture more diverse evolutionary patterns.

Integration with Protein Language Model Training

Pretraining Data Curation Strategies

The curation of pretraining datasets from these resources significantly impacts pLM performance. Most modern Transformer-based protein models, including ESM, ProtBERT, and ProGen, use single amino acid tokenization (1-mer) to preserve biological granularity, treating each amino acid as a discrete token [28]. Standard pretraining objectives include Masked Language Modeling (MLM), where random amino acids are masked and the model is trained to reconstruct them, and autoregressive next-token prediction, commonly used in decoder-only architectures like ProtGPT2 for sequence generation [26].

Training data is typically sourced from large-scale protein databases including UniRef (50/90/100), Swiss-Prot, TrEMBL, and BFD, sometimes encompassing over 50 million sequences [26]. The upcoming reorganization of UniProtKB, expected through 2025-2026, will limit UniProtKB/TrEMBL sequences to those derived from reference proteomes (unless they have significant additional functional information), reducing the total entries from ~253 million to ~141 million [30]. This deliberate reduction in redundancy aims to improve biodiversity representation, though researchers should note that removed sequences will be archived in UniParc and remain accessible via their stable EMBL Protein IDs [30].

Model Architectures and Database Utilization

Different pLM architectures leverage these databases in distinct ways. Encoder-only models (BERT-style), such as ESM-1b and ProtBERT, use UniRef and BFD for pretraining via MLM objectives, generating contextual embeddings for each residue suitable for per-residue tasks like contact prediction or variant effect analysis [26]. Decoder-only models (GPT-style), including ProGen and ProtGPT2, are trained autoregressively on these databases for sequence generation tasks [28] [26]. Encoder-decoder models (T5-style) apply sequence-to-sequence frameworks, potentially using Swiss-Prot's high-quality annotations for fine-tuning on function prediction [26].

Table 2: pLMs and Their Training Data Sources

| Protein Language Model | Architecture Type | Primary Data Sources | Notable Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| ESM (Evolutionary Scale Modeling) | Encoder-only | UniRef, BFD [29] | Structure/function prediction [28] |

| ProtBERT | Encoder-only | UniRef100 [28] | Protein sequence function prediction [28] |

| ProGen, ProtGPT2 | Decoder-only | UniRef, metagenomic data [28] [26] | De novo protein sequence generation [28] |

| AlphaFold (Evoformer) | Hybrid (MSA Integration) | BFD, UniRef, MGNify [29] | Protein structure prediction [29] |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Workflow: Protein Complex Structure Prediction with DeepSCFold

The DeepSCFold pipeline exemplifies how sequence databases enable high-accuracy protein complex structure modeling by leveraging sequence-derived structure complementarity [29]. This approach is particularly valuable for complexes lacking clear co-evolutionary signals, such as antibody-antigen systems.

Diagram: DeepSCFold uses pSS-scores and pIA-scores with monomeric MSAs to build paired MSAs for accurate complex prediction [29].

Protocol: Constructing Paired MSAs for Complex Prediction

- Input Query Sequences: Begin with protein complex subunit sequences (e.g., antibody-antigen pairs) [29].

- Generate Monomeric MSAs: Use sequence search tools (HHblits, Jackhmmer, MMseqs2) against databases including UniRef, BFD, and MGnify to create individual MSAs for each subunit [29].

- Predict Structural Similarity (pSS-score): Use a deep learning model to predict protein-protein structural similarity purely from sequence information, providing a complementary metric to traditional sequence similarity for ranking monomeric MSA homologs [29].

- Predict Interaction Probability (pIA-score): Employ a sequence-based deep learning model to estimate interaction probability between potential pairs of sequence homologs from distinct subunit MSAs [29].

- Construct Paired MSAs: Systematically concatenate monomeric homologs using pIA-scores and integrate multi-source biological information (species annotations, UniProt accessions, PDB complexes) to build biologically relevant paired MSAs [29].

- Structure Prediction and Selection: Execute AlphaFold-Multimer with the constructed pMSAs, then select the top model using quality assessment methods like DeepUMQA-X for final output [29].

Protocol: pLM Fine-tuning for Functional Annotation

- Base Model Selection: Choose a pre-trained pLM (e.g., ESM-2, ProtBERT) that has been trained on large-scale databases like UniRef [28] [26].

- Curate Fine-tuning Dataset: Extract sequences and annotations from Swiss-Prot for the target function (e.g., enzyme commission numbers, Gene Ontology terms) [27].

- Adapt Model Architecture: Add a task-specific classification head on top of the pre-trained Transformer encoder [26].

- Supervised Fine-tuning: Train the model on the annotated dataset, typically using cross-entropy loss for classification tasks [26].

- Validation: Evaluate model performance on held-out test sets from Swiss-Prot, using metrics such as precision, recall, and F1-score [26].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Resources for Protein Language Model Research

| Resource/Reagent | Type | Function in Research | Access Information |

|---|---|---|---|

| UniProt REST API | Web Service | Programmatic access to UniProtKB, UniRef, UniParc; enables automated data retrieval for large-scale analyses [25] | https://www.uniprot.org/api-documentation |

| HH-suite | Software Suite | Sensitive sequence searching against BFD and other large databases; constructs MSAs for co-evolutionary analysis [29] | https://github.com/soedinglab/hh-suite |

| AlphaFold-Multimer | Software | Predicts protein complex structures using paired MSAs derived from sequence databases [29] | https://github.com/deepmind/alphafold |

| ESM Model Variants | Pre-trained Models | Protein language models pre-trained on UniRef and BFD data; can be fine-tuned for specific prediction tasks [28] [26] | https://github.com/facebookresearch/esm |

| ColabFold DB | Database | Integrated database combining UniRef, BFD, MGnify, and PDB sequences; optimized for fast MSA construction [29] | https://colabfold.mmseqs.com |

Future Directions and Database Evolution

The landscape of protein databases continues to evolve, with significant implications for pLM research. UniProt's forthcoming reorganization to focus on reference proteomes will fundamentally change the sequence space available in UniProtKB, though archived sequences will remain accessible via UniParc [27] [30]. This shift aims to improve biodiversity representation while maintaining data quality. Emerging trends include the development of multi-modal models that integrate sequence, structure, and textual information, requiring more sophisticated database architectures to serve interconnected data types [26]. The research community is also placing greater emphasis on standardized benchmarking (e.g., ProteinGym, TAPE) to fairly evaluate pLMs trained on different data sources [26]. As scaling laws from NLP are adapted to protein sequences, the optimal balance between model size, dataset diversity, and computational budget continues to be refined, with current evidence suggesting that single-pass training on diverse, high-quality data may outperform multiple passes on larger but redundant datasets [26].

Transformer Architectures in Action: From Structure Prediction to De Novo Drug Design

The application of Transformer-based language models to protein sequences represents a paradigm shift in computational biology, enabling unprecedented capabilities in protein structure prediction, functional annotation, and de novo protein design. These models treat amino acid sequences as a biological "language," learning complex patterns from millions of natural protein sequences. Within this context, several landmark architectures have emerged with distinct capabilities: ESM (Evolutionary Scale Modeling) series for structure and function prediction, ProtTrans for scalable pre-training and functional annotation, AlphaFold for revolutionary structure prediction accuracy, and ProtGPT2 for generative protein design. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical analysis of these architectures, their experimental methodologies, and their transformative impact on biological research and therapeutic development.

Core Architectural Specifications

Table 1: Comparative specifications of landmark protein language models

| Model | Architecture Type | Training Data Scale | Key Output | Primary Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ProtTrans | Transformer-based [31] | 393 billion amino acids [32] | Sequence embeddings [33] | Protein function prediction [33] [32] |

| AlphaFold2 | Evoformer + Structure Module | Not specified | 3D atomic coordinates [34] | Protein structure prediction [34] |

| ProtGPT2 | GPT-2 decoder-only [35] | 50 million sequences (UniRef50) [35] | Novel protein sequences [35] | De novo protein design [35] |

| ESM | BERT-style [34] | Not specified | Sequence representations [34] | Structure/function prediction [34] |

Performance Metrics and Applications

Table 2: Quantitative performance and biological applications

| Model | Key Performance Metric | Biological Validation | Therapeutic Relevance |

|---|---|---|---|

| ProtTrans | Outperforms other tools in per-protein annotation [33] | Accurate identification of secondary active transporters [32] | Cancer-related transporter identification [32] |

| AlphaFold2 | Atomic accuracy in CASP14 [36] | Comparable to experimental methods [36] | Drug target identification [36] |

| EQAFold (AlphaFold enhancement) | Average pLDDT error: 4.74 (vs AF2 5.16) [34] | Tested on 726 monomeric proteins [34] | Improved confidence for drug discovery [34] |

| ProtGPT2 | 88% of generated proteins predicted globular [35] | Distantly related to natural sequences [35] | Exploration of novel protein space [35] |

Detailed Model Architectures and Methodologies

ProtTrans: Scalable Protein Representation Learning

ProtTrans represents one of the most ambitious efforts in scalable protein language model pre-training, utilizing 5616 GPUs and TPUs to train on 393 billion amino acid sequences [32]. The model employs a standard Transformer architecture similar to BERT, processing protein sequences as tokens and generating meaningful embeddings that capture evolutionary and structural information. These embeddings serve as input features for downstream tasks including functional annotation, secondary structure prediction, and membrane protein classification [33] [32].

In practical implementation, ProtTrans embeddings have been successfully integrated with deep learning networks for specific biological applications. For instance, the FANTASIA tool leverages ProtTrans for functional annotation based on embedding space similarity, enabling large-scale annotation of uncharacterized proteomes [33]. Similarly, ProtTrans embeddings combined with multiple window scanning convolutional neural networks have achieved high accuracy (MCC: 0.759) in identifying secondary active transporters from membrane proteins, demonstrating clinical relevance for cancer research [32].

AlphaFold2 and EQAFold: Revolutionizing Structure Prediction

AlphaFold2 represents a watershed moment in protein structure prediction, solving the 50-year-old protein folding problem through an innovative architecture that combines Evoformer modules with a structure module [36]. The system begins with multiple sequence alignment (MSA) generation, processes this through the Evoformer to create single and pair representations, then iteratively refines these through the structure module to produce atomic-level 3D coordinates with remarkable accuracy [36].

The recently introduced EQAFold (Equivariant Quality Assessment Folding) framework enhances AlphaFold2 by replacing the standard Local Distance Difference Test (LDDT) prediction head with an equivariant graph neural network (EGNN) [34]. This innovation addresses a critical limitation where poorly modeled protein regions were sometimes assigned high confidence scores. EQAFold constructs a graph representation where nodes represent amino acids and edges connect residues within 16Å, with node features incorporating Evoformer representations, ESM2 embeddings, and root mean square fluctuation (RMSF) values from multiple dropout replicates [34].

ProtGPT2: Generative Protein Design

ProtGPT2 implements a GPT-2 decoder-only architecture with 738 million parameters trained on UniRef50 using an autoregressive training objective [35]. The model learns to predict the next amino acid in a sequence given all previous context, enabling it to generate novel protein sequences with natural-like properties. Critical to its success is the implementation of appropriate sampling strategies—while greedy search and beam search produce repetitive sequences, random sampling with top-k=950 and a repetition penalty of 1.2 generates sequences with amino acid propensities matching natural proteins [35].

The model demonstrates remarkable biological realism, with 88% of generated proteins predicted to be globular, matching the proportion observed in natural sequences [35]. Generated sequences are evolutionarily distant from natural proteins yet maintain structural integrity, as confirmed by AlphaFold structure predictions that reveal well-folded structures with novel topologies not present in current databases [35]. This capability enables exploration of "dark" regions of protein space, potentially unlocking novel functions for therapeutic applications.

Experimental Protocols and Implementation

EQAFold Training and Evaluation Methodology

The EQAFold framework was trained and evaluated using rigorously curated datasets to ensure biological relevance and avoid overfitting:

Dataset Curation:

- Source: PISCES protein sequence culling server [34]

- Inclusion criteria: Monomeric protein structures with resolution ≤2.5Å

- Training set: 11,966 entries

- Test set: 726 entries

- Sequence similarity: ≤40% between training and test sets [34]

Feature Engineering:

- Node features: Concatenated Evoformer representations (L×384), averaged ESM layers (L×33), and RMSF values (L×1)

- Edge features: Pair embeddings (L×L×128) and averaged ESM attention layers (L×L×33)

- Graph construction: Residues within 16Å connected as edges [34]

Network Architecture:

- EGNN with 4 equivariant graph convolutional layers

- 384 input node features, 128 hidden features, 50 output features

- Training: Fine-tuned on pre-trained AlphaFold2 model [34]

Evaluation Metrics:

- Primary: pLDDT error (difference between predicted and true LDDT)

- Benchmarking: Compared against standard AlphaFold2 on 726 test proteins

- Results: EQAFold achieved 4.74 average pLDDT error vs 5.16 for standard AlphaFold2 [34]

ProtGPT2 Sequence Generation and Validation

ProtGPT2 employs sophisticated sampling strategies and multi-tier validation to ensure generated protein sequences exhibit natural-like properties:

Sampling Strategy Optimization:

- Greedy search: Produces deterministic, repetitive sequences

- Beam search: Improved but still suffers from repetitiveness

- Random sampling with top-k=950: Achieves natural amino acid propensities [35]

- Repetition penalty: 1.2 to avoid sequence degeneration [35]

Validation Pipeline:

- Amino acid propensity analysis: Compare distributions with natural sequences from UniRef50

- Structural disorder prediction: Assess globular vs disordered regions (88% globular) [35]

- Evolutionary distance assessment: Sensitive sequence searches against natural databases

- Structural validation: AlphaFold structure prediction of generated sequences

- Stability analysis: Predicted stability and dynamic properties comparison [35]

Experimental Findings:

- Generated sequences are evolutionarily distant from natural proteins

- AlphaFold predictions reveal well-folded structures with novel topologies

- Exploration of unexplored regions of protein space while maintaining foldability [35]

Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Table 3: Essential research reagents and computational tools for protein language model implementation

| Tool/Resource | Type | Function | Access |

|---|---|---|---|

| UniRef50 | Dataset | Curated protein sequence database at 50% identity | https://www.uniprot.org/ |

| FANTASIA | Software Tool | Functional annotation using ProtTrans embeddings | https://github.com/MetazoaPhylogenomicsLab/FANTASIA [33] |

| OpenFold | Software Framework | Open-source AlphaFold2 implementation | https://github.com/aqlaboratory/openfold [34] |

| ProtGPT2 Weights | Model Parameters | Pre-trained weights for sequence generation | https://huggingface.co/nferruz/ProtGPT2 [35] |

| PISCES Server | Curation Tool | Protein sequence culling for dataset creation | http://dunbrack.fccc.edu/pisces/ [34] |

| EQAFold Code | Software | Enhanced quality assessment for AlphaFold | https://github.com/kiharalab/EQAFold_public [34] |

The landmark architectures of ESM, ProtTrans, AlphaFold, and ProtGPT2 represent a transformative era in computational biology, where Transformer-based models have fundamentally altered our approach to protein science. These models demonstrate complementary strengths: ProtTrans provides scalable representations for functional annotation, AlphaFold delivers unprecedented structural accuracy, EQAFold enhances confidence estimation, and ProtGPT2 enables creative exploration of novel protein space.

Future developments are likely to follow several convergent trajectories: the replacement of handcrafted features with unified token-level embeddings, a shift from single-modal to multimodal architectures, the emergence of AI agents capable of scientific reasoning, and movement beyond static structure prediction toward dynamic simulation of protein function [37]. These advancements promise to deliver increasingly intelligent, generalizable, and interpretable AI platforms that will accelerate therapeutic discovery and deepen our understanding of fundamental biological processes.

The prediction of protein three-dimensional (3D) structure from amino acid sequence represents a central challenge in computational biology. The remarkable success of deep learning, particularly transformer-based Protein Language Models (PLMs), has revolutionized this field by achieving unprecedented accuracy. These models infer complex physical and evolutionary constraints directly from sequences, allowing them to predict 3D folds with near-experimental accuracy for many proteins [38] [39]. This technical guide explores the architectures, methodologies, and mechanisms by which PLMs decode the linguistic patterns of protein sequences to accurately infer their native structures, a capability with profound implications for drug discovery and protein engineering [38].

Foundations of Protein Language Models

Architectural Principles

Protein Language Models are built upon the transformer architecture, which utilizes self-attention mechanisms to weigh the importance of different amino acids in a sequence when constructing representations. PLMs are typically pre-trained on vast datasets of protein sequences, such as UniRef, using self-supervised objectives like masked language modeling [2] [40]. In this pre-training phase, random amino acids in sequences are masked, and the model learns to predict them based on their context, thereby internalizing fundamental principles of protein biochemistry, evolutionary constraints, and structural relationships without explicit structural supervision [40] [3].