Overcoming Data Scarcity in Protein Engineering: AI-Driven Strategies for Success with Limited Experimental Data

This article provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a comprehensive framework for advancing protein engineering projects when experimental data is scarce.

Overcoming Data Scarcity in Protein Engineering: AI-Driven Strategies for Success with Limited Experimental Data

Abstract

This article provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a comprehensive framework for advancing protein engineering projects when experimental data is scarce. It explores the fundamental challenges of limited data, details cutting-edge computational methods like latent space optimization and Bayesian optimization, offers practical troubleshooting for uncertainty quantification, and presents rigorous validation protocols. By synthesizing insights from recent algorithmic advances and real-world case studies on proteins like GFP and AAV, this guide enables more efficient and reliable protein design under data constraints, accelerating therapeutic and industrial applications.

The Data Dilemma: Understanding the Core Challenges of Limited Data in Protein Engineering

Why Limited Data is a Fundamental Bottleneck in Protein Design

In protein engineering and drug discovery, the ability to design and optimize proteins is constrained by a fundamental challenge: the severely limited availability of high-quality experimental data. While computational methods, particularly deep learning, have advanced rapidly, their performance and reliability are intrinsically linked to the quantity and quality of the data on which they are trained. This article establishes a technical support framework to help researchers diagnose, troubleshoot, and overcome data-related bottlenecks in their protein design projects.

The Core Problem: Quantifying Data Scarcity

The following table summarizes key evidence of data limitations in structural biology and its impact on molecular design.

Table 1: Evidence and Impact of Limited Data in Protein Design

| Aspect of Scarcity | Quantitative Evidence | Direct Consequence |

|---|---|---|

| Publicly Available Protein-Ligand Complexes | Fewer than 200,000 complexes are public [1] | Models struggle to learn transferable geometric priors and overfit to training-set biases [1]. |

| Experimentally Solved Protein Structures | ~177,000 structures in the PDB; 155,000 from X-ray crystallography [2] | High cost and time requirements limit data for modeling proteins without homologous counterparts [2]. |

| Performance in Data-Scarce Regimes | IBEX raised docking success from 53% to 64% by better leveraging limited data [1] | Highlights the significant performance gains possible with improved data-utilization strategies. |

| Marginal Stability of Natural Proteins | A large fraction of proteins exhibit low stability, hindering experimentation [3] | Limits heterologous expression, reducing the number of proteins amenable to high-throughput screening [3]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) & Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ 1: My structure-based generative model for molecular design is overfitting to the training set and fails to generalize. What strategies can I use?

- Problem Diagnosis: This is a classic symptom of training a complex model on a small dataset. The model memorizes the training examples' biases rather than learning the underlying physics of binding.

- Recommended Solutions:

- Leverage a Coarse-to-Fine Pipeline: Implement a framework like IBEX, which separates information-rich generation from physics-guided refinement. This reduces the search space during generation and uses a subsequent optimization step (e.g., L-BFGS) to refine conformations based on physics-based terms like van-der-Waals attraction and hydrogen-bond energy [1].

- Reframe the Task: If your goal is de novo generation, try training your model on a related task with higher information density, such as Scaffold Hopping. Research shows this can endow the model with greater effective capacity and improved transfer performance, even for de novo tasks [1].

- Incorporate Synthetic Data: Augment your experimental data with computationally generated structures. For example, the ESM-IF1 model was trained on a mix of thousands of experimental structures and millions of AlphaFold2-predicted structures, drastically expanding the effective training dataset [4].

FAQ 2: I want to predict protein fitness, but I have a very small set of labeled variants. How can I build a reliable model?

- Problem Diagnosis: Supervised machine learning requires a substantial amount of labeled data to generalize. When labeled protein-fitness pairs are scarce, model performance plummets.

- Recommended Solutions:

- Employ Semi-Supervised Learning (SSL): Use the vast number of evolutionarily related (homologous) sequences as unlabeled data to improve your model. SSL leverages the latent information in these sequences to compensate for the lack of labels [5].

- Select an Effective SSL Strategy:

- Unsupervised Pre-processing: Encode your labeled sequences using methods that incorporate information from unlabeled homologous sequences. Prominent options include Direct Coupling Analysis (DCA) encoding and eUniRep [5].

- Wrapper Methods: Use methods like the Tri-Training Regressor (an adaptation for regression problems) or Co-Training. These methods use base estimators to generate pseudo-labels for unlabeled data, which are then safely incorporated into the training set in an iterative process [5].

- Adopt a Hybrid Framework: Implement the MERGE method, which combines a DCA model (derived from unlabeled sequences) with a supervised regressor (e.g., SVM) trained on your labeled data. This has been shown to outperform other encodings when labeled data is low [5].

FAQ 3: I need to optimize an existing protein for stability or expression, but experimental screening is low-throughput. How can computational design help?

- Problem Diagnosis: Optimizing a protein often requires testing many mutations, but low-throughput assays restrict the number of variants you can evaluate.

- Recommended Solutions:

- Use Evolution-Guided Atomistic Design: This strategy combines structure-based calculations with evolutionary information. First, analyze the natural diversity of homologous sequences to filter out rare, destabilizing mutations. Then, perform atomistic design calculations to stabilize the desired protein state within this reduced, evolutionarily validated sequence space [3].

- Apply Active Learning: If you can perform sequential rounds of experimentation, use an active learning cycle. Train an initial model on your available data, use it to query the sequence space for regions of high uncertainty, experimentally test those specific variants, and then append the new data to your training set for the next iteration. This efficiently focuses experimental resources on the most informative data points [4].

Experimental Protocols for Data-Limited Scenarios

Protocol 1: Semi-Supervised Protein Fitness Prediction with MERGE and DCA

This protocol is adapted from recent research showing success with limited labeled data [5].

- Input: A small set of labeled protein variants (sequences and fitness values) and a target protein of interest.

- Homology Search: Use the target protein's sequence to perform a homology search (e.g., with HHblits or Jackhmmer) to build a Multiple Sequence Alignment (MSA) from a large database of unlabeled, evolutionarily related sequences.

- Direct Coupling Analysis (DCA): Use the MSA to infer a DCA statistical model. This model captures the co-evolutionary couplings between residue pairs.

- Feature Extraction:

- Calculate the statistical energy for each of your labeled sequences using the DCA model.

- Use the parameters of the DCA model to encode each labeled sequence into a numerical feature vector.

- Model Training: Train a supervised regression model (e.g., Support Vector Regressor (SVR)) using the features from the previous step. The model learns to predict fitness from the DCA-based encodings.

- Prediction: For a new, unlabeled sequence, compute its DCA-based features and statistical energy, then input them into the trained SVR to predict its fitness.

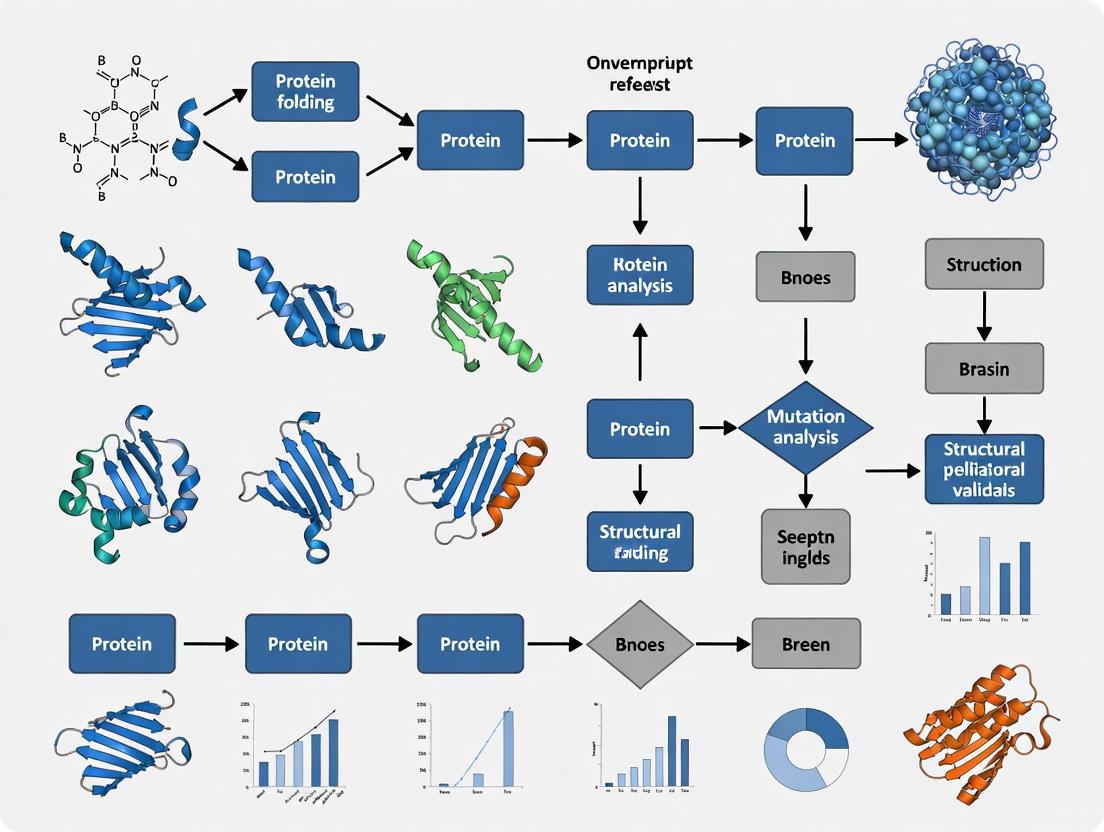

The workflow for this protocol is illustrated below.

Protocol 2: Coarse-to-Fine Molecular Generation with Refinement

This protocol is based on the IBEX pipeline, which is designed to improve generalization with limited protein-ligand complex data [1].

- Input: A dataset of protein-ligand complexes (e.g., CrossDocked2020).

- Coarse Generation: Train an SE(3)-equivariant diffusion model (e.g., TargetDiff) to generate candidate ligand molecules and their conformations directly within the protein pocket. To improve data efficiency, consider training on a scaffold-hopping task where key functional groups are fixed.

- Physics-Based Refinement: For each generated molecule and its coarse conformation, treat the ligand as a rigid body and perform a limited-memory BFGS (L-BFGS) optimization. The objective function to be minimized should include:

- Van-der-Waals attraction

- Steric repulsion

- Hydrogen-bond energy

- Output: The refined molecule with an optimized binding pose and improved binding affinity (Vina score).

Table 2: Essential Computational Tools for Data-Driven Protein Design

| Tool / Resource Name | Type | Primary Function in Protein Design |

|---|---|---|

| IBEX Pipeline [1] | Generative Model | A coarse-to-fine molecular generation pipeline that uses information-bottleneck theory and physics-based refinement to improve performance with limited data. |

| MERGE with DCA [5] | Semi-Supervised Learning Framework | A hybrid method that uses evolutionary information from unlabeled sequences to boost fitness prediction models when labeled data is scarce. |

| ESM-IF1 [4] | Inverse Folding Model | A deep learning model that can be used for zero-shot prediction tasks or fine-tuned on specific families. It can also generate synthetic structural data for training. |

| ChimeraX / PyMOL [6] | Molecular Visualization | Software for analyzing and presenting molecular structures, critical for validating designed proteins or generated ligands. |

| Rosetta [2] | Modeling Suite | A comprehensive platform for protein structure prediction, design, and refinement, including protocols for docking and side-chain optimization. |

The bottleneck of limited data in protein design is a persistent but not insurmountable challenge. By moving beyond purely supervised methods and adopting sophisticated strategies—such as semi-supervised learning, evolutionary guidance, task reframing, and hybrid physical-DL frameworks—researchers can significantly enhance the efficacy and reliability of their computational designs. The troubleshooting guides and protocols provided here offer a practical starting point for integrating these data-efficient approaches into your research workflow.

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: Our lab has very limited budget for high-throughput experimentation. How can we still generate meaningful data for machine learning? A1: Focus on strategic data acquisition. Instead of random mutagenesis, use computational tools to identify key "hotspot" positions for mutation [7]. Additionally, employ Few-Shot Learning strategies, which can optimize protein language models using only tens of labeled single-site mutants, dramatically reducing the required experimental data [8].

Q2: Our experimental data is low-throughput and prone to variability. How can we ensure its quality for building reliable models? A2: Robust quality control is non-negotiable. Implement these best practices [9]:

- Assay Validation: Before full screening, confirm your assay's pharmacological relevance and reproducibility using known controls.

- Plate Design: Include positive and negative controls on each assay plate to monitor performance and identify systematic errors like edge effects.

- QC Metrics: Use statistical metrics like Z'-factor to quantitatively assess assay quality across plates and runs.

Q3: How can we validate our computational designs without incurring massive synthesis and testing costs? A3: Participate in community benchmarking initiatives. The Protein Engineering Tournament provides a platform where participants' computationally designed protein sequences are synthesized and experimentally tested for free by the organizers, providing crucial validation data without individual cost [10] [11] [12].

Q4: What can we do to manage our limited experimental data effectively to ensure it can be reused and shared? A4: Adopt rigorous data management practices [13]:

- Preserve Raw Data: Always store the original, unprocessed data files in a write-protected, open format (e.g., CSV) to ensure authenticity.

- Document Extensively: Maintain comprehensive metadata, including detailed experimental protocols and instrument calibration data.

- Clean Data Thoughtfully: Document all data cleaning procedures (e.g., normalization, handling of outliers) to minimize information loss and bias.

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Hurdles

Problem: High rate of false positives in initial screening.

- Cause: Compounds may exhibit auto-fluorescence, form aggregates causing non-specific inhibition, or belong to classes known as Pan-Assay Interference Compounds (PAINS) [9].

- Solution:

- Implement counter-screens that use a different detection principle or mechanism to filter out artifactual hits [9].

- Use computational filters to flag compounds with known PAINS substructures [9].

- Consider Mass Spectrometry-based HTS, which directly detects unlabeled analytes and avoids common optical interference, though it requires specialized equipment [9].

Problem: Low protein expression and stability hinders functional assays.

- Cause: Many natural proteins are marginally stable, leading to poor expression in heterologous hosts, low yields, and difficulty in introducing beneficial mutations without compromising folding [3].

- Solution: Utilize structure-based stability design methods. These computational approaches can suggest stabilizing mutations, often leading to variants with identical or improved function that can be expressed efficiently in systems like E. coli, reducing production costs and time [3].

Problem: Predicting and improving enzyme stereoselectivity is experimentally intensive.

- Cause: The high cost and labor intensity of measuring enantiomeric excess (ee) values leads to a severe scarcity of high-quality stereoselectivity data, limiting model development [14].

- Solution: Standardize all stereoselectivity measurements to relative activation energy differences (ΔΔG≠), which unifies different metrics (ee, E value) across studies [14]. Develop machine learning models that use hybrid feature sets combining 3D structural information and physicochemical properties to capture subtle differences in enzyme-substrate interactions [14].

Key Methodologies and Workflows

The following workflow illustrates an integrated computational and experimental pipeline designed to operate effectively under data and resource constraints.

Optimizing Proteins with Limited Data

Detailed Protocol: Applying Few-Shot Learning for Fitness Prediction

This protocol is based on the FSFP method, which enhances protein language models with minimal wet-lab data [8].

Objective: Improve the accuracy of a Protein Language Model (PLM) for predicting the fitness of your target protein using a very small dataset (e.g., 20-100 labeled mutants).

Materials:

- Computing Resources: Access to a computing environment (e.g., provided by sponsors like Modal Labs in tournaments [12] or local servers).

- Pre-trained Model: A pre-trained Protein Language Model (e.g., ESM-1v, ESM-2, SaProt).

- Target Protein Data: A small set of experimentally characterized variants (sequence and fitness value) for your target protein.

- Auxiliary Data: Public deep mutational scanning (DMS) datasets (e.g., from ProteinGym benchmark) for meta-training.

Procedure:

- Step 1: Meta-Training Preparation

- Build auxiliary tasks by finding the top two proteins in a database like ProteinGym that are most similar to your target protein in the PLM's embedding space.

- Generate a third auxiliary task by using an alignment-based method (e.g., GEMME) to score candidate mutants of your target protein, creating pseudo-labels.

- Step 2: Model-Agnostic Meta-Learning (MAML)

- Use the MAML algorithm to meta-train the PLM on the three auxiliary tasks. This involves:

- Inner Loop: For a sampled task, initialize a temporary model with the current meta-learner's weights and update it using the task's training data.

- Outer Loop: Compute the test loss of this temporary model and use it to update the meta-learner's weights.

- To prevent overfitting, use Parameter-Efficient Fine-Tuning (e.g., Low-Rank Adaptation - LoRA) during this process, which freezes the original PLM weights and only updates a small set of injected parameters.

- Use the MAML algorithm to meta-train the PLM on the three auxiliary tasks. This involves:

- Step 3: Transfer Learning to Target Task

- Initialize your model with the meta-trained weights from Step 2.

- Fine-tune the model on your small, target protein dataset. Frame the problem as a Learning to Rank task instead of regression.

- Use the ListMLE loss function, which trains the model to learn the correct ranking order of variants by fitness, rather than predicting absolute fitness values.

- Step 4: Prediction and Validation

- Use the fine-tuned model to predict and rank novel protein variants.

- Select top-ranked candidates for experimental validation in the lab.

- Step 1: Meta-Training Preparation

Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

The following table details key resources that support protein engineering under constraints.

| Item | Function in Research | Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| Synthetic DNA (e.g., Twist Bioscience) | Bridges digital designs with biological reality; synthesizes variant libraries and novel gene sequences for testing. | Critical for validating computational predictions. Sponsorships in tournaments can provide free access [12]. |

| Pre-trained Protein Language Models (e.g., ESM, SaProt) | Provides a powerful base for fitness prediction without initial experimental data; encodes evolutionary information. | Can be fine-tuned with minimal data using few-shot learning techniques for improved accuracy [8]. |

| High-Quality Public Datasets (e.g., ProteinGym) | Serves as benchmark for model development and source of auxiliary data for meta-learning and transfer learning. | Essential for pre-training and benchmarking models when in-house data is scarce [11] [8]. |

| Stability Design Software | Computationally predicts mutations that enhance protein stability and expression, improving experimental success rates. | Methods like evolution-guided atomistic design can dramatically increase functional protein yields [3]. |

Quantitative Data and Metrics

The table below summarizes key cost and performance metrics relevant to constrained research environments.

| Metric | Typical Value/Range | Impact on Constraints | Source / Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Classical Drug Discovery Cost | >$2.5 billion per drug | Highlights immense financial pressure to optimize early R&D. | [9] |

| Phase 1 Attrition Rate | >80-90% | Underlines need for better predictive models to avoid costly late-stage failures. | [9] |

| Data for Model Improvement | ~20 single-site mutants | Demonstrates that significant performance gains are possible with very small, targeted datasets. | [8] |

| Performance Gain (Spearman) | Up to +0.1 | Quantifies the improvement in prediction accuracy achievable with few-shot learning on limited data. | [8] |

The Perils of Rugged Fitness Landscapes and Epistatic Interactions

Welcome to the Technical Support Center

This resource provides troubleshooting guides and FAQs for researchers navigating the challenges of rugged fitness landscapes and epistatic interactions in protein engineering. The guidance is framed within the critical thesis that successful engineering in the face of limited experimental data requires strategies that explicitly account for, and even leverage, epistasis.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: Why do my protein variants, designed using rational, additive models, consistently fail to exhibit the predicted functions? This failure is likely due to epistasis—the non-additive, often unpredictable interactions between mutations within a protein sequence [15]. In a rugged fitness landscape shaped by strong epistasis, the effect of a mutation depends on its genetic background. A mutation that is beneficial in one sequence can become deleterious in another. Purely additive models ignore these interactions, leading to inaccurate predictions when multiple mutations are combined [16].

FAQ 2: Our deep mutational scanning (DMS) data only covers a local region of sequence space. Can we use it to predict function in distant regions? This is a high-risk endeavor due to the potential for higher-order epistasis. While local data can be well-explained by additive and pairwise effects, predictions for distant sequences often require accounting for interactions among three or more residues [17]. One study found that the contribution of higher-order epistasis to accurate prediction can be negligible in some proteins but critical in others, accounting for up to 60% of the epistatic component when generalizing to distant sequences [17].

FAQ 3: How can we experimentally detect if a fitness landscape is rugged? A key signature of a rugged landscape is specificity switching and the presence of multiple fitness peaks. In a study of the LacI/GalR transcriptional repressor family, researchers characterized 1,158 sequences from a phylogenetic tree. They observed an "extremely rugged landscape with rapid switching of specificity, even between adjacent nodes" [16]. If your experiments show that a few mutations can drastically alter or even reverse function, you are likely dealing with a rugged landscape.

FAQ 4: What computational tools can help us model higher-order epistasis for a full-length protein? Traditional regression methods fail for full-length proteins because the number of possible higher-order interactions explodes exponentially. A modern solution is the use of specialized machine learning models. The "epistatic transformer" is a neural network architecture designed to implicitly model epistatic interactions up to a specified order (e.g., pairwise, four-way, eight-way) without an unmanageable number of parameters, making it scalable to full-length proteins [17].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Low Predictive Accuracy from Additive Models

Symptoms:

- The functional output of multi-mutant variants deviates significantly from the sum of individual mutation effects.

- Designed combinatorial libraries show a high fraction of non-functional variants.

Diagnosis: You are operating in a rugged fitness landscape where epistasis is a dominant factor [15] [16].

Solutions:

- Incorporate Pairwise and Higher-Order Epistasis into Models: Move beyond linear models. Employ machine learning frameworks, like the epistatic transformer, that can capture specific epistatic interactions [17].

- Account for Global Epistasis: Model your sequence-function relationship using a two-component framework:

g(ϕ(x))whereϕ(x)captures specific epistasis between amino acids, and the nonlinear functiongaccounts for global, non-specific epistasis that shapes the overall fitness landscape [17]. - Use Evolution-Guided Design: Analyze natural sequence diversity to identify positions that are conserved or co-vary. This evolutionary information can act as a negative design filter, helping to avoid mutations that lead to misfolding or instability, thereby simplifying the fitness landscape [3].

Issue: Difficulty Extrapolating from Local to Global Sequence Space

Symptoms:

- Models trained on local single- and double-mutant data perform poorly when predicting the function of triple mutants or sequences with multiple mutations.

- Difficulty in identifying viable evolutionary paths toward a desired function.

Diagnosis: Higher-order epistatic interactions (involving three or more residues) become significant outside the locally sampled data [17].

Solutions:

- Systematically Test Interaction Orders: Fit a series of models with increasing epistatic complexity (e.g., additive, pairwise, four-way). If predictive accuracy on a held-out test set—particularly one containing higher-order mutants—improves significantly, you have evidence that higher-order epistasis is important for your system [17].

- Prioritize Sparse Data Collection: If resources are limited, use model uncertainty to guide experiments. Focus on characterizing variants that the model is most uncertain about, which often lie in regions of sequence space influenced by higher-order interactions.

Issue: Navigating Multi-Peak Landscapes to Avoid Evolutionary Dead Ends

Symptoms:

- Evolution gets "stuck" on a local fitness peak and cannot reach a higher, global peak without traversing a fitness valley (deleterious mutations).

- Observed evolutionary paths show "switch-backs," where populations alternate adaptations to different selective pressures (e.g., different antibiotics) [15].

Diagnosis: The fitness landscape contains multiple peaks separated by valleys, a direct result of epistasis [16].

Solutions:

- Map Ancestral Paths: Use Ancestral Sequence Reconstruction (ASR) to infer historical sequences and then characterize them experimentally. This can reveal viable, historical paths through the landscape that might not be apparent from extant sequences alone [16].

- Analyze Drug Combinations with Care: In antibiotic development, be aware that using non-interacting drug pairs can sometimes accelerate the evolution of dual resistance through positive epistasis and mutational switch-backs. A deeper understanding of how drug combinations affect adaptation is required [15].

The table below consolidates key findings on the role and impact of epistasis from recent research.

| Protein/System | Key Finding on Epistasis | Quantitative Impact / Prevalence | Experimental Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| 10 Combinatorial Protein DMS Datasets [17] | Contribution of higher-order epistasis to prediction | Ranged from negligible to ~60% of the epistatic variance | Epistatic Transformer ML Model |

| LacI/GalR Repressor DBDs [16] | Landscape ruggedness and specificity switching | Extremely rugged landscape; rapid specificity switches between 1,158 nodes | Ancestral Sequence Reconstruction & Deep Mutational Scanning |

| Self-cleaving Ribozyme [15] | Prevalence of negative epistasis | Extensive pairwise & higher-order epistasis impedes prediction | High-throughput sequencing & ML |

| Francisella tularensis [15] | Role of positive epistasis in antibiotic resistance | Contributed to accelerated evolution of dual drug resistance | Experimental evolution & genomics |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Characterizing a Fitness Landscape via Deep Mutational Scanning

Objective: To empirically measure the function of tens of thousands of protein variants and map the local fitness landscape.

Key Reagents:

- Gene Library: A comprehensive oligo library encoding the designed variants (e.g., all single mutants, all pairwise mutants of a region of interest).

- Selection System: A high-throughput assay that links protein function to a selectable or scorable output (e.g., cell growth, fluorescence, binding to a labeled target).

- Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) Platform: For quantifying the enrichment or depletion of each variant before and after selection.

Workflow:

- Library Construction: Synthesize the DNA library and clone it into an appropriate expression vector.

- Transformation & Expression: Introduce the library into a host cell line and induce protein expression.

- Selection/Assay: Apply the functional assay to separate functional variants from non-functional ones.

- Sequencing: Isolve DNA from the pre-selection (input) and post-selection (output) populations and perform NGS.

- Fitness Calculation: Calculate a fitness score for each variant based on its enrichment in the output library relative to the input.

Protocol 2: Quantifying Higher-Order Epistasis with an Epistatic Transformer

Objective: To fit a model that isolates and quantifies the contribution of higher-order epistasis to protein function [17].

Key Reagents:

- Large Protein Sequence-Function Dataset: A DMS dataset or equivalent with measured functions for a large number of variants.

- Computational Framework: Implementation of the epistatic transformer architecture (typically in Python with PyTorch/TensorFlow).

Workflow:

- Data Preparation: Split the dataset into training and test sets. Ensure the test set includes variants with multiple mutations.

- Model Training: Fit a series of epistatic transformer models with an increasing number of attention layers (M). Each increase allows the model to capture higher-order interactions (up to order 2M).

- Model Evaluation: Compare the predictive performance (e.g., R² correlation) of each model on the held-out test set.

- Variance Decomposition: The improvement in model accuracy with added layers indicates the contribution of higher-order epistasis. The total variance explained can be partitioned into additive, pairwise, and higher-order components.

Evaluating Higher-Order Epistasis

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Key Consideration for Epistasis |

|---|---|---|

| Combinatorial DNA Library | Simultaneously tests a vast number of protein variants. | Essential for empirically detecting interactions between mutations; local libraries miss higher-order effects [17]. |

| Epistatic Transformer Model | Machine learning model to predict function and quantify interaction orders. | Scalable to full-length proteins; allows control over maximum epistasis order fitted [17]. |

| Ancestral Sequence Reconstruction (ASR) | Infers historical protein sequences to map evolutionary paths. | Reveals viable paths through rugged landscapes and historical specificity switches [16]. |

| Stability Design Software | Computationally optimizes protein stability via positive/negative design. | Improved stability provides a robust scaffold, potentially mitigating some destabilizing epistatic effects during engineering [3]. |

Common Scenarios Leading to Sparse Datasets in Research and Development

Frequently Asked Questions

1. What are the primary sources of sparse data in protein engineering? Sparse data in protein engineering typically arises from three areas: the high cost and labor intensity of wet-lab experiments, the limitations of high-throughput screening, and the inherent complexity of protein fitness landscapes. Generating reliable data, especially on properties like stereoselectivity, is expensive and time-consuming, meaning that comprehensive mapping of sequence-function relationships is often practically impossible [14]. Furthermore, high-throughput methods, while generating more data points, can still only cover a minuscule fraction of the nearly infinite protein sequence space [3] [18]. Finally, complex properties governed by non-linear and epistatic interactions require dense sampling to model accurately, which exacerbates the data scarcity problem [18].

2. How can I effectively run experiments when I have low traffic or a small sample size? When experimental throughput is low, strategic adjustments are crucial. Focus your resources by testing bold, high-impact changes that users are likely to notice and engage with. Simplify your experimental design to an A/B test with only two variations to maximize the traffic allocated to each. You can also consider increasing your statistical significance threshold (e.g., from 0.05 to 0.10) for lower-risk experiments, as this reduces the amount of data needed to detect an effect. Finally, use targeted metrics that are directly related to the change being tested, such as micro-conversions, which are more sensitive than overarching macro-conversions [19].

3. My ML model for fitness prediction performs well on held-out test data but fails in real-world design. Why? This is a classic sign of overfitting and a failure to extrapolate. Models trained on small datasets are prone to learning patterns that exist only in your local, limited training data and do not generalize to distant regions of the fitness landscape [18] [20]. Protein engineering is an extrapolation task; you are using a model trained on a tiny subset of sequences to design entirely new ones. Simpler models or model ensembles can sometimes be more robust for this task. Ensuring your training data is as diverse as possible and using techniques like transfer learning can also improve the model's ability to generalize [21] [18].

4. Are there specific machine learning techniques suited for small data regimes in protein science? Yes, several techniques are particularly valuable. Transfer learning has shown remarkable performance, where a model pre-trained on a large, general protein dataset (like a protein language model) is fine-tuned on your small, specific dataset [21]. Choosing simpler models with fewer parameters, like logistic regression or linear models, can reduce overfitting [20]. Implementing model ensembles, which combine predictions from multiple models, can also make protein engineering efforts more robust and accurate by averaging out errors [18].

5. What wet-lab strategies can help overcome the data bottleneck? Adopting semi-automated and high-throughput experimental platforms is key to breaking this bottleneck. Integrated platforms can dramatically increase data generation by using miniaturized, parallel processing (e.g., in 96-well plates), sequencing-free cloning for speed, and automated data analysis [22]. Furthermore, innovative methods to slash DNA synthesis costs, which can be a major expense, are critical. For example, constructing sequence-verified clones from inexpensive oligo pools can reduce DNA construction costs by 5- to 8-fold, enabling the testing of thousands of designs [22].

Troubleshooting Guide: Solving Common Sparse Data Problems

| Problem Symptom | Potential Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| High predictive error on new, designed variants | Model overfitting; failure to extrapolate | Use simpler models (e.g., Linear Regression), implement model ensembles, or apply transfer learning with a pre-trained model [18] [20] [21]. |

| Inability to reach statistical significance in tests | Low sample size or underpowered experimental design | Test bold changes, limit to 2 variations (A/B), raise the significance threshold for low-risk contexts, and use targeted primary metrics [19]. |

| High cost and slow pace of experimental validation | Manual, low-throughput wet-lab workflows | Implement a semi-automated protein production platform (e.g., SAPP workflow) and leverage low-cost DNA construction methods (e.g., DMX) [22]. |

| Model predictions are unstable and vary greatly | High variance due to limited data and model complexity | Utilize ensemble methods that output the median prediction from multiple models to reduce variance and increase robustness [18]. |

| Lack of generalizability across protein families or substrates | Data is too specific and scarce for robust learning | Employ multimodal ML architectures that combine sequence and structural information, and use transfer learning to leverage larger, related datasets [14]. |

Experimental Protocols for Data-Efficient Research

Protocol 1: Semi-Automated Protein Production (SAPP) for High-Throughput Validation This protocol is designed to rapidly generate high-quality protein data from DNA constructs, bridging the gap between in silico design and empirical validation [22].

- Sequencing-Free Cloning: Use Golden Gate Assembly with a vector containing a suicide gene (e.g., ccdB). This achieves ~90% cloning accuracy, eliminating the need for time-consuming colony picking and sequence verification.

- Miniaturized Expression: Conduct protein expression in a 96-well deep-well plate using auto-induction media to remove the need for manual induction.

- Parallel Purification & Analysis: Perform a two-step purification (e.g., nickel-affinity and size-exclusion chromatography) in parallel. The size-exclusion chromatography (SEC) step simultaneously provides data on purity, yield, oligomeric state, and dispersity.

- Automated Data Processing: Use open-source software to automatically analyze thousands of SEC chromatograms, standardizing data output for downstream analysis.

This workflow enables a 48-hour turnaround from DNA to purified protein with approximately six hours of hands-on time [22].

SAPP Experimental Workflow

Protocol 2: Leveraging Transfer Learning for Fitness Prediction with Small Datasets This protocol outlines a methodology for applying deep transfer learning to predict protein fitness when labeled data is scarce [21].

- Base Model Selection: Start with a pre-trained protein language model (e.g., ProteinBERT) that has been trained on a large, diverse corpus of protein sequences in an unsupervised manner. This model has learned general evolutionary and structural patterns.

- Model Adaptation: Replace the output layer of the pre-trained model to suit your specific prediction task (e.g., regression for fitness value).

- Fine-Tuning: Train (fine-tune) the entire model on your small, labeled dataset. Use a low learning rate to gently adapt the general-purpose knowledge to your specific problem without catastrophic forgetting.

- Model Evaluation: Rigorously evaluate the model's performance using cross-validation and on held-out test sets, comparing its performance to supervised methods trained from scratch.

This approach allows the model to leverage broad biological knowledge, making it more robust and accurate in low-data scenarios [21].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Oligo Pools | A cost-effective source of DNA encoding thousands of variant genes for library construction [22]. |

| Vectors with Suicide Genes (e.g., ccdB) | Enables high-fidelity, sequencing-free cloning by selecting only for correctly assembled constructs [22]. |

| Auto-induction Media | Simplifies and automates protein expression in high-throughput formats by removing the need for manual induction [22]. |

| Pre-trained Protein Language Models (e.g., ESM2) | Provides a foundational model of protein sequences that can be fine-tuned for specific prediction tasks, reducing the need for large labeled datasets [21] [23]. |

| 96-well Deep-well Plates | The standard format for miniaturized, parallel processing of samples in automated or semi-automated platforms [22]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What are the most common causes of data loss in a research setting? Data loss can occur through hardware failure (e.g., hard drive crashes), human error (e.g., accidental deletion, working with outdated dataset versions), software errors (e.g., spreadsheet reformatting data), insufficient documentation, and failure during data migration. The loss of associated metadata and experimental context can be as damaging as the loss of raw data itself [24] [25].

How can I improve the reproducibility of my high-throughput screens? Focus on rigorous assay validation, strategic plate design with positive and negative controls, and monitoring key quality control metrics like the Z'-factor to ensure robust and reproducible results. Implementing automation can reduce manual variability, but it must be integrated into a cohesive workflow to be effective [9].

My proteomics data has a lot of missing values. How should I handle this? Missing values are a common challenge in single-cell proteomics and other high-throughput techniques. Strategies include using statistical methods to reduce sparsity, followed by careful application of missing value imputation algorithms such as k-nearest neighbors (kNN) or random forest (RF). The choice of method should be evaluated to avoid introducing artifactual changes [26] [27].

What is the difference between a backup and an archive? A backup is designed for disaster recovery and should be loadable back into an application quickly, within the uptime requirements of your service. An archive is for long-term safekeeping of data to meet compliance needs; its recovery is not typically time-sensitive. For active research data, you need real backups [28].

Why is a Data Management Plan (DMP) important? A DMP provides a formal framework that defines folder structures, data backup schedules, and team roles regarding data handling. It helps prevent data loss, ensures everyone follows the same protocols, and is often a requirement from public funding agencies [13] [24].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Diagnosing and Recovering from General Data Loss

This guide addresses general data loss scenarios, from hardware failure to accidental deletion.

Step 1: Identify the Source and Scope

- Action: Determine which data sources, pipelines, or systems are affected. Quantify how much data is missing or corrupted.

- Tools: Use data quality dashboards, data lineage diagrams, and system log files to track the issue. Use validation techniques like checksums to compare expected versus actual data [25].

Step 2: Analyze the Root Cause

- Action: Understand why the error occurred. Was it a hardware fault, a software bug, a configuration error, or human action?

- Tools: Use debugging tools, code analysis software, and incident response tools to examine the code, configuration, or environment that caused the error [25].

Step 3: Recover or Restore the Data

- Action: Execute your recovery plan using available backups.

- Tools: Use backup and recovery tools to restore data. A robust strategy follows the 3-2-1 Rule: keep 3 copies of your data on 2 different media, with 1 copy stored offsite [24]. For corrupted data, use data cleansing or transformation tools to repair it [25].

Step 4: Prevent Future Loss

- Action: Implement proactive measures.

- Tools:

- Electronic Lab Notebooks (ELNs): Securely store and organize research records with automated metadata [24].

- Version Control & Monitoring: Use tools like Git for code and configuration, and implement monitoring systems with alerts for anomalies [25].

- Regular Training: Ensure all team members are trained on data management protocols and the use of shared systems [29].

Guide 2: Troubleshooting High-Throughput Screening (HTS) Data Quality

This guide helps identify and correct common issues that compromise the quality of HTS data.

Symptom: Poor reproducibility across assay plates.

- Potential Cause: Edge effects due to evaporation or temperature gradients in microplates [9].

- Solution:

Symptom: High rate of false positives.

- Potential Cause: Compound interference, such as auto-fluorescence, aggregation, or belonging to a class of Pan-Assay Interference Compounds (PAINS) [9].

- Solution:

- Implement Counter-screens: Use secondary assays with different detection principles (e.g., orthogonal assays) to filter out artifactual hits [9].

- Use Computational Filters: Apply PAINS substructure filters to flag potentially problematic compounds early in the analysis [9].

- Alternative Methods: Consider using label-free detection methods or mass spectrometry-based HTS, which are less prone to certain optical artifacts [9].

Symptom: Data handling has become a major bottleneck.

- Potential Cause: Disparate data formats, manual data transcription, and lack of integrated data management infrastructure [9].

- Solution:

- Automate Data Capture: Use integrated data management solutions, such as a Laboratory Information Management System (LIMS), to automate data capture from instruments and standardize formats [9].

- Adopt Advanced Data Analysis Pipelines: Implement automated or machine learning-guided data analysis pipelines to handle the scale and complexity of HTS datasets [9].

The table below summarizes key statistical metrics used to quantitatively assess the quality of an HTS assay [9].

| Metric | Formula | Interpretation | Ideal Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Z'-Factor | ( 1 - \frac{3(\sigma{p} + \sigma{n})}{ | \mu{p} - \mu{n} | } ) | Assay quality and suitability for HTS; incorporates dynamic range and data variation. | > 0.5 |

| Signal-to-Noise Ratio (S/N) | ( \frac{ | \mu{p} - \mu{n} | }{\sigma_{n}} ) | Ratio of the desired signal to the background noise. | > 10 |

| Signal-to-Background Ratio (S/B) | ( \frac{\mu{p}}{\mu{n}} ) | Ratio of the signal in the positive control to the negative control. | > 10 | ||

| Coefficient of Variation (CV) | ( \frac{\sigma}{\mu} \times 100\% ) | Measure of precision and reproducibility within replicates. | < 10% |

HTS Data Analysis Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Category | Item | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| Software & Informatics | DIA-NN | A popular software tool for data-independent acquisition (DIA) mass spectrometry data analysis, known for its sensitivity in single-cell proteomics [26]. |

| Spectronaut | Another leading software for DIA data analysis, often noted for high proteome coverage and detection capabilities [26]. | |

| Electronic Lab Notebook (ELN) | Digital tool for securely storing, organizing, and backing up research records. Ensures data is traceable and protected from physical damage or loss [24]. | |

| Data Management | Laboratory Information Management System (LIMS) | Software-based system for tracking samples, associated data, and workflows in the laboratory, improving data integrity and operational efficiency [9]. |

| Data Governance Platform (e.g., Collibra) | Provides comprehensive solutions for data cataloging, policy management, and lineage tracking, ensuring data is trustworthy and well-managed [29]. | |

| Molecular Biology Reagents | TEV Protease (TEVp) | A highly specific model protease often used in protein engineering and in developing novel screening platforms, such as DNA recorders for specificity profiling [30]. |

| Phage Recombinase (Bxb1) | An enzyme used in advanced genetic recorders. Its stability can be made dependent on protease activity, enabling the linking of biological activity to a DNA-based readout [30]. | |

| Stability & Expression | Proteolytic Degradation Signal (SsrA) | A peptide tag that targets proteins for degradation in cells. Used in engineered systems to link protease activity to the stability of a reporter protein [30]. |

Advanced Methodologies for Data-Rich Protein Engineering

Experimental Protocol: DNA Recorder for Deep Protease Specificity Profiling

This protocol enables high-throughput collection of sequence-activity data for proteases against numerous substrates in parallel [30].

- Construct Plasmid Architecture: Create a plasmid with expression cassettes for the candidate protease and the phage recombinase Bxb1. Fuse Bxb1 to a C-terminal peptide containing the protease substrate (TEVs) followed by an SsrA degradation tag. Include a recombination array flanked by Bxb1's attachment sites [30].

- Cell Culture and Induction: Transform the plasmid into an appropriate E. coli strain. Grow the culture and induce expression of Bxb1 at an optimized time point [30].

- Sample Collection and DNA Extraction: Draw samples at different time points post-induction. Extract plasmids from these samples [30].

- NGS Library Preparation: Isolate target fragments containing protease and substrate barcodes and the recombination array via a PCR-free protocol. Ligate fragments to Illumina-compatible adapters with sample-specific indices and pool for sequencing [30].

- Data Processing and Analysis: Process NGS data to obtain the sequences of the protease and substrate candidates and calculate the "fraction flipped" over time. This flipping curve correlates directly with the proteolytic activity for each protease-substrate pair [30].

DNA Recorder Workflow Principle

Practical AI and Computational Strategies for Protein Design with Sparse Data

Protein engineering is fundamental to developing new therapeutics, enzymes, and diagnostics. However, a significant bottleneck in this field is the limited availability of high-quality experimental data, which makes it challenging to train robust models for predicting protein fitness and function. Wet lab researchers often operate with small, expensive-to-generate datasets [21]. Latent Space Optimization (LSO) emerges as a powerful strategy to address this challenge. LSO involves performing optimization tasks within a compressed, abstract representation—or latent space—of a generative model [31] [32]. This approach allows researchers to efficiently navigate the vast space of possible protein sequences to find variants with desired properties, even when starting with limited data.

FAQs and Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ 1: What is Latent Space Optimization, and why is it particularly useful when experimental data is limited?

Latent Space Optimization (LSO) is a technique where optimization algorithms search through the latent space of a generative model to find inputs that produce outputs with optimal properties [33]. Instead of searching through the impossibly large space of all possible protein sequences (data space), you search a simpler, continuous latent space that captures the essential features of functional proteins [31] [32].

This is exceptionally useful with limited data because:

- Efficiency: The latent space is a compressed, lower-dimensional representation, making the optimization problem computationally more tractable [32] [33].

- Data Leverage: You can leverage pre-trained generative models (e.g., Protein Language Models) that have learned the "rules" of protein sequences from vast public databases. This prior knowledge helps guide the search toward viable protein sequences, even with limited project-specific data [34] [21].

- Constraint Encoding: The latent space inherently captures the relationships and patterns of the training data, helping to avoid the generation of nonsensical or non-functional sequences [31].

Troubleshooting Guide 1: My LSO process is generating protein sequences that are unstable or non-functional. What could be wrong?

This is a common challenge, often resulting from the model prioritizing the objective function (e.g., binding affinity) at the expense of fundamental protein stability.

- Potential Cause 1: The generative model was not trained to account for thermodynamic stability.

- Solution:

- Incorporate Stability Metrics: Integrate a stability metric directly into your objective function. For example, the PREVENT model successfully learned the sequence-to-free-energy relationship, ensuring generated variants were thermodynamically stable [35].

- Use a Regularization Term: Add a regularization term to your optimization objective that penalizes sequences with high predicted free energy (ΔG) [36].

- Potential Cause 2: The optimization process has strayed into an unstable region of the latent space.

- Solution:

- Apply Constraints: Use methods like surrogate latent spaces, which define a custom, bounded search space using a few known stable sequences as "seeds." This ensures the optimization remains within model-supported regions that generate valid outputs [33].

- Refine the Model: Employ strategies like evolution-guided atomistic design, which filters mutation choices based on natural sequence diversity to eliminate destabilizing mutations before the atomistic design step [3].

Troubleshooting Guide 2: I have a very small dataset of labeled protein sequences for my target property. How can I effectively apply LSO?

With small datasets, the key is to leverage knowledge from larger, related datasets.

- Potential Cause: The model is overfitting to the small dataset and failing to generalize.

- Solution:

- Utilize Deep Transfer Learning: Start with a model pre-trained on a massive corpus of protein sequences (e.g., ESM2). Then, fine-tune this model on your small, specific dataset. Studies have shown that deep transfer learning excels in small dataset scenarios for protein fitness prediction, outperforming traditional supervised and semi-supervised methods [21].

- Multi-Likelihood Optimization: As proposed in recent research, train your generative model by optimizing the likelihood of your data in both the amino acid sequence space and the latent space of a pre-trained protein language model. This acts as a functional validator and helps distill broader knowledge into your model [34].

FAQ 2: How does LSO compare to traditional methods like Directed Evolution?

Directed Evolution (DE) is a powerful but laborious experimental process that involves generating vast mutant libraries and screening them for desired traits [35] [3]. LSO offers a computational acceleration to this process.

- LSO uses models to intelligently navigate the sequence space, proposing a focused set of promising candidates for experimental testing. The PREVENT model, for example, used LSO to design 40 variants of an E. coli enzyme, with 85% found to be functional [35].

- Key Advantage: LSO dramatically reduces the number of variants that need to be synthesized and screened experimentally, saving significant time and resources, which is crucial when data and resources are limited [35] [3].

Quantitative Performance of LSO Methods

The table below summarizes the performance of various LSO-related approaches as reported in recent literature.

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Recent LSO-Related Methods in Protein Engineering

| Method / Model | Primary Task | Reported Performance | Key Innovation |

|---|---|---|---|

| PREVENT [35] | Generate stable/functional protein variants | 85% of generated EcNAGK variants were functional; 55% showed similar growth rate to wildtype. | Learns sequence-to-free-energy relationship using a VAE. |

| Deep Transfer Learning (e.g., ProteinBERT) [21] | Protein fitness prediction on small datasets | State-of-the-art performance on small datasets; outperforms supervised & semi-supervised methods. | Leverages pre-trained models fine-tuned on limited task-specific data. |

| Surrogate Latent Spaces [33] | Controlled generation in complex models (e.g., proteins) | Enabled generation of longer proteins than previously feasible; improved success rate of generations. | Defines a custom, low-dimensional latent space for efficient optimization. |

| Latent-Space Codon Optimizer (LSCO) [36] | Maximize protein expression via codon optimization | Outperformed frequency-based and naturalness-driven baselines in predicted expression yields. | Combines data-driven expression objective with MFE regularization in latent space. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Protein Variant Generation using a VAE-based LSO Framework (based on PREVENT [35])

This protocol outlines the steps for generating thermodynamically stable protein variants using a Variational Autoencoder (VAE).

Input Dataset Creation:

- Perform in silico mutagenesis on a wildtype protein sequence (e.g., generate ~100,000+ unique variants with up to 15% mutated residues).

- Compute the associated folding free energy (ΔG) for each variant using a forcefield-based tool like FOLDX.

- Split the dataset into training/validation (90%) and a held-out test set (10%).

Model Training:

- Architecture: Use a Transformer-based VAE.

- Training Setup:

- Train the model to reconstruct protein sequences from the training set.

- Simultaneously, train a regression head on the latent space to predict the ΔG value for each sequence.

- Use a latent space dimension of 128, a learning rate of 10⁻⁴, and apply regularization (e.g., dropout of 0.2).

Latent Space Optimization:

- Encode the training sequences into the latent space.

- Navigate this latent space (e.g., via gradient-based optimization or sampling) to find latent points (z) that are decoded into novel sequences and are predicted by the regression head to have low ΔG (high stability).

Experimental Validation:

- Select top-ranked generated variants for synthesis and wet lab testing.

- Assay for functionality (e.g., ability to complement a knockout strain) and stability.

Diagram 1: VAE-based LSO workflow for generating stable protein variants.

Protocol 2: Optimization in a Surrogate Latent Space for Controlled Generation [33]

This protocol is useful for applying LSO to complex generative models (like diffusion models) for tasks such as generating proteins with specific properties.

Seed Selection:

- Choose K example data points (e.g., K=3) that possess properties related to your goal. For a protein, these could be known stable structures.

- Use the generative model's inversion process (if deterministic) to map these seeds to their latent representations, z₁ ... zₖ.

Construct Surrogate Space:

- Define a (K-1)-dimensional bounded space, 𝒰 = [0,1]^K⁻¹.

- Create a mapping from any point u in 𝒰 to a unique latent vector z in the model's full latent space. This creates a custom, low-dimensional "surrogate latent space."

Perform Black-Box Optimization:

- Define your objective function f(x) that scores a generated protein x on your desired property (e.g., predicted fitness).

- Use a black-box optimizer like Bayesian Optimization (BO) or CMA-ES to solve: u∗ = argmax_{u in 𝒰} f(g(z(u))), where g is the generative model.

Validation:

- Decode the optimal z* into its protein sequence and validate computationally and experimentally.

Diagram 2: Surrogate latent space optimization for controlled generation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 2: Essential Computational Tools for LSO in Protein Engineering

| Tool / Resource | Function / Description | Application in LSO |

|---|---|---|

| Pre-trained Protein Language Models (e.g., ESM2) [34] | Deep learning models trained on millions of protein sequences to understand evolutionary constraints. | Provides a rich latent space for feature extraction, sequence generation, and as a functional validator. |

| Generative Model Architectures (VAE, GAN, Diffusion) [35] [33] | Models that can learn data distributions and generate novel, similar samples. | The core engine for creating the latent space that LSO navigates. |

| Free Energy Calculation Tools (e.g., FOLDX) [35] | Forcefield-based software for rapid computational estimation of protein stability (ΔG). | Used to label training data and as a regularization objective to ensure generated proteins are stable. |

| Black-Box Optimizers (e.g., BO, CMA-ES) [33] | Algorithms designed to find the maximum of an unknown function with minimal evaluations. | The "search" algorithm that efficiently explores the latent space to find optimal sequences. |

| Surrogate Latent Space Framework [33] | A method to construct a custom, low-dimensional latent space from example seeds. | Enables efficient and reliable LSO on complex modern generative models like diffusion models. |

The following table summarizes the key quantitative results from the evaluation of GROOT on biological sequence optimization tasks, demonstrating its effectiveness with limited data.

| Task | Dataset Size | Key Performance Result | Comparative Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Green Fluorescent Protein (GFP) | Extremely limited (<100 labeled sequences) | 6-fold fitness improvement over training set [37] | Performs stably where other methods fail [37] |

| Adeno-Associated Virus (AAV) | Extremely limited (<100 labeled sequences) | 1.3 times higher fitness than training set [37] | Outperforms previous state-of-the-art baselines [37] |

| Various Tasks (Design-Bench) | Limited labeled data | Competitive with state-of-the-art approaches [37] | Highlights domain-agnostic capabilities (e.g., robotics, DNA) [37] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the core innovation of the GROOT framework? GROOT introduces a novel graph-based latent smoothing technique to address the challenge of limited labeled experimental data in biological sequence design. It generates pseudo-labels for neighbors sampled around training data points in a latent space and refines them using Label Propagation. This creates a smoothed fitness landscape, enabling more effective optimization than the original, sparse data allows [37].

Q2: Why do existing methods fail with very limited labeled data, and how does GROOT solve this? Standard surrogate models trained on scarce labeled data are highly vulnerable to noisy labels, often leading to sampling false negatives or getting trapped in suboptimal local minima. GROOT addresses this by regularizing the fitness landscape. It expands the effective training set through synthetic sample generation and graph-based smoothing, which enhances the model's predictive ability and guides optimization more reliably [37].

Q3: In which practical scenarios would GROOT be most beneficial for my research? GROOT is particularly powerful in scenarios where wet-lab experiments are costly and time-consuming, thus severely limiting the amount of available labeled fitness data. It has been proven effective in protein optimization tasks like enhancing Green Fluorescent Protein (GFP) and Adeno-Associated Virus (AAV) with fewer than 100 known sequences. Its domain-agnostic design also makes it suitable for other fields like robotics and DNA sequence design [37].

Q4: How does GROOT ensure that its extrapolations into new regions of the latent space are reliable? The GROOT framework is supported by a theoretical justification that guarantees its extrapolation remains within a reasonable upper bound of the expected distances from the training data regions. This controlled exploration helps reduce prediction errors for unseen points that would otherwise be too far from the original training set, maintaining reliability while discovering novel, high-fitness sequences [37].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Suboptimal or Poor-Quality Sequence Outputs

- Potential Cause: The surrogate model is overfitting to the noise in the very small initial labeled dataset.

- Solution:

- Verify Latent Space Construction: Ensure the encoder network is properly trained to map sequences to a meaningful latent representation. The quality of the graph depends on this.

- Check Graph Parameters: Review the criteria for building the graph from latent embeddings (e.g., the number of neighbors considered for each node). Adjusting the graph's connectivity can improve the smoothness of the propagated labels.

- Validate Pseudo-Labels: Monitor the Label Propagation process. The refined pseudo-labels for synthesized nodes should form a smoother fitness landscape than the original, noisy data.

Problem 2: Failure to Find Sequences Better than the Training Data

- Potential Cause: The optimization algorithm is trapped in a local minimum of the unsmoothed fitness landscape.

- Solution:

- Leverage the Smoothed Model: Confirm that the optimization algorithm (e.g., gradient ascent) is using the surrogate model trained on the smoothed data from GROOT, not the model trained on the raw, limited data. This model should have a less rugged landscape.

- Explore Extrapolation Boundaries: The theoretical foundation of GROOT allows for safe extrapolation. Ensure the optimization process is configured to explore regions just beyond the immediate neighborhood of the training data, as GROOT is designed to be reliable in these areas.

Problem 3: High Computational Cost during the Training Phase

- Potential Cause: The graph construction and Label Propagation scale with the number of nodes (both original and synthesized).

- Solution:

- Manage Synthetic Sample Volume: While generating synthetic samples is key, start with a moderate number of interpolated neighbors. The method is designed to be effective even with limited data, so excessive synthesis may not be necessary.

- Optimize Graph Structure: Use an efficient graph structure and a fixed number of nearest neighbors for graph construction to prevent the graph from becoming too large and computationally expensive to process.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Core GROOT Workflow for Protein Sequence Optimization

This protocol details the steps to apply the GROOT framework to a protein optimization task such as enhancing GFP or AAV fitness [37].

Data Preparation and Latent Encoding:

Graph Construction and Synthetic Sampling:

- Form a graph where each node is a latent vector ( z ) from the training data, with the node attribute being its fitness value ( y ) [37].

- For each training data point, sample new latent embeddings in its neighborhood (e.g., via interpolation with nearby points). These new nodes are initially unlabeled [37].

Label Propagation and Landscape Smoothing:

- Apply a Label Propagation algorithm on the constructed graph. This algorithm iteratively propagates fitness labels from the labeled training nodes to the unlabeled, synthesized nodes based on the graph's connectivity, generating pseudo-labels for them [37].

- The result is a expanded and smoothed dataset containing both original and synthetic points with refined fitness values.

Surrogate Model Training and Sequence Optimization:

- Train a surrogate model (e.g., a neural network) ( f_{\Phi} ) to predict fitness from the latent space using this smoothed dataset [37].

- Use an optimization algorithm (e.g., gradient ascent) within the latent space to find points ( z^* ) that maximize the prediction of the smoothed surrogate model ( f_{\Phi} ) [37].

- Decode the optimized latent vector ( z^* ) back into a biological sequence ( s^* ) using the decoder component of the model.

Protocol 2: In-silico Benchmarking with an Oracle

This protocol is for researchers who wish to evaluate GROOT's performance using a publicly available benchmark with a simulated oracle, such as those found in Design-Bench [37].

Dataset and Oracle Setup:

- Select a task from a benchmark suite (e.g., GFP, AAV, or a non-biological task from Design-Bench).

- Use the provided dataset ( \mathcal{D}^* ) of sequences and fitness measurements. Artificially limit this dataset to simulate a low-data scenario [37].

- Train an oracle model ( \mathcal{O}_{\psi} ) on the full dataset ( \mathcal{D}^* ) to act as a high-fidelity simulator for the black-box function [37].

Model Training and Evaluation:

- Apply the Core GROOT Workflow (Protocol 1) using only the limited subset of data.

- Generate proposed optimal sequences ( s^* ) using GROOT.

- Evaluate the true fitness of the proposed sequences ( s^* ) using the pre-trained oracle ( \mathcal{O}_{\psi} ) to validate performance against other methods [37].

Visualization of GROOT's Architecture and Logic

The following diagram illustrates the core architecture of GROOT, showing how it transforms limited labeled data into a smoothed fitness model for reliable optimization.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table lists key components and their functions within the GROOT framework, acting as the essential "reagents" for computational experiments.

| Component / 'Reagent' | Function in the GROOT Framework |

|---|---|

| Encoder Model | Maps discrete, high-dimensional biological sequences into a continuous, lower-dimensional latent space where operations can be performed [37]. |

| Graph Structure | Represents the relationship between latent vectors. Nodes are data points, and edges connect similar sequences, enabling the propagation of information [37]. |

| Label Propagation Algorithm | The core "smoothing" agent that diffuses fitness labels from known sequences to synthesized neighboring points in the graph, creating a regularized fitness landscape [37]. |

| Surrogate Model (( f_{\Phi} )) | A neural network trained on the smoothed dataset to predict the fitness of any point in the latent space, guiding the optimization process [37]. |

| Optimization Algorithm | (e.g., Gradient Ascent). Navigates the smoothed latent space using the surrogate model to find latent points ( z^* ) that correspond to sequences with predicted high fitness [37]. |

| Decoder Model | Translates the optimized latent vector ( z^* ) back into a concrete, discrete biological sequence ( s^* ) that can be synthesized and tested in the lab [37]. |

How Pseudo-Labeling and Label Propagation Enhance Limited Datasets

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the core semi-supervised learning scenarios in bioinformatics? Semi-supervised learning (SSL) is primarily used to overcome the challenge of limited labelled data, which is common in experimental biology. The main scenarios are:

- Unsupervised Pre-processing: Information from a large number of unlabelled sequences (e.g., homologous sequences) is used to create better features or models. These enhanced features are then used to train a supervised model on the small labelled dataset. Methods like MERGE and eUniRep encoding fall into this category [5].

- Wrapper Methods: A supervised model is first trained on the limited labelled data. This model is then used to predict pseudo-labels on the unlabelled data. The safest and most confident pseudo-labels are added to the training set, and the process repeats iteratively. Tri-Training and Co-Training are examples of this approach [5].

Q2: My model's performance plateaued after introducing pseudo-labels. What could be wrong? This is a common issue in wrapper methods. The likely cause is error propagation from incorrectly pseudo-labelled data. To troubleshoot:

- Check Pseudo-label Certainty: Implement a certainty measure, such as calculating the entropy of the predictions. Only incorporate pseudo-labels with the highest certainty (lowest entropy) into your training set [38].

- Review Data Quality: The performance of methods like label propagation is highly dependent on the quality of the initial labelled data and the underlying network (e.g., PPI network). Noisy or biased input data will lead to degraded performance [39].

- Stagger the Integration: Gradually increase the number of pseudo-labelled examples added in each iteration, rather than adding a large batch at once, to allow the model to adjust more stably [5].

Q3: How do I handle ambiguous or uncertain experimental data in structure prediction? Traditional methods assume all experimental data is correct, which can lead to errors when data is sparse or semireliable. The MELD (Modeling Employing Limited Data) framework addresses this by using a Bayesian approach.

- Principle: Instead of using all data restraints at once, MELD's likelihood function actively identifies and ignores the least reliable data points for a given structure. For example, if you have 100 predicted contacts but know only about 65 are correct, MELD will, for each conformation, consider the 35 least-satisfied restraints as incorrect and only enforce the top 65. This sculpts a multi-funneled energy landscape that guides the search to the correct structure [40].

Q4: Can I use these methods with very deep protein language models (PLMs)? Yes, and specific strategies have been developed for this purpose. The FSFP (Few-Shot Learning for Protein Fitness Prediction) strategy is designed to optimize large PLMs with minimal wet-lab data.

- Key Techniques: It combines meta-transfer learning to find a good model initialization from related tasks, learning to rank (LTR) to focus on the relative order of fitness rather than precise values, and parameter-efficient fine-tuning (like LoRA) to avoid overfitting by only updating a small subset of parameters [8]. This approach has been shown to significantly boost the performance of models like ESM-1v and ESM-2 with only tens of labelled examples [8].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Poor Model Generalization on Limited Labelled Data

Problem: A supervised model trained on a small dataset of labelled protein variants fails to accurately predict the fitness of new, unseen variants.

Solution: Employ a semi-supervised learning strategy to leverage unlabelled homologous sequences.

Required Materials:

- Labelled Data: A small set of protein variants with experimentally measured fitness values.

- Unlabelled Data: A larger set of evolutionarily related protein sequences (homologs).

- Computational Tools: Software for multiple sequence alignment (MSA) and a machine learning library (e.g., scikit-learn).

Step-by-Step Protocol: Using the MERGE Method [5]

Data Collection & Pre-processing:

- Gather your small set of labelled protein sequences and their fitness values.

- Perform a homology search (e.g., using HMMER against UniRef) for your protein of interest to build a multiple sequence alignment (MSA) with unlabelled related sequences.

Unsupervised Feature Extraction (Direct Coupling Analysis - DCA):

- Use the MSA to infer a DCA statistical model. This model captures the co-evolutionary constraints between residue pairs.

- Use the DCA model for two purposes:

- Predict the "statistical energy" for any given sequence in an unsupervised manner.

- Use its parameters to encode your labelled sequences into numerical feature vectors (DCA encoding).

Supervised Model Training:

- Train a supervised regression model (e.g., Ridge Regression or SVM) using the DCA-encoded features of your labelled sequences as input and their experimental fitness as the target output.

Fitness Prediction:

- To predict the fitness of a new, unlabelled variant, the model's output is complemented by adding the unsupervised statistical energy from the DCA model. This hybrid approach combines evolutionary information with supervised learning from labelled data.

Issue: Propagating Noisy Labels in a Biological Network

Problem: A label propagation algorithm on a Protein-Protein Interaction (PPI) network is producing unreliable predictions, likely due to false-positive interactions in the network data.

Solution: Implement a method that can learn and correct for noise in the network itself, such as the Improved Dual Label Propagation (IDLP) framework [39].

Required Materials:

- Network Data: A PPI network (e.g., from BioGRID) and a phenotype similarity network.

- Association Data: Known gene-phenotype associations (e.g., from OMIM).

- Computational Environment: A platform capable of performing matrix operations and optimization (e.g., Python with NumPy/SciPy).

Step-by-Step Protocol: The IDLP Framework [39]

Network Construction:

- Construct a heterogeneous network by linking the PPI network and the phenotype similarity network using the known gene-phenotype associations.

Model Formulation:

- The key innovation of IDLP is to treat the adjacency matrices of the PPI network ((S1)) and the phenotype network ((S2)) as variables to be learned, rather than fixed inputs.

- The objective function minimizes a loss that includes:

- Label Propagation Loss: Ensures that genes/phenotypes close in the network have similar labels.

- Reconstruction Error: Keeps the learned networks ((S1), (S2)) close to their original, noisy versions ((\bar{S}1), (\bar{S}2)).

- Fitting Error: Ensures the predicted associations ((Y)) do not deviate too much from the known ones ((\hat{Y})).

Optimization:

- The loss function is optimized to simultaneously learn the corrected gene-phenotype association matrix ((Y)), a denoised PPI network ((S1)), and a denoised phenotype network ((S2)).

- This is typically done by alternately optimizing for (Y), (S1), and (S2) until convergence, with each step having a closed-form solution for efficiency.

Prediction:

- After optimization, the genes with the highest scores in the learned association matrix (Y) for a given phenotype are prioritized as the most likely disease genes.

The following diagram illustrates the flow of information and the core iterative process of the IDLP framework:

Experimental Workflow: Label Propagation for Deep Semi-Supervised Learning

This workflow, adapted from computer vision, is highly applicable for tasks like classifying protein sequences or images from limited labelled examples [38].

Protocol: Iterative Label Propagation with a Deep Neural Network

- Initial Supervised Training: Start by training a deep neural network (e.g., a CNN or a protein-specific LM) on the limited set of labelled examples ((XL), (YL)) using a standard cross-entropy loss.

- Descriptor Extraction: For the entire dataset (both labelled and unlabelled), pass the inputs through the network and extract the descriptor vectors from the layer just before the final classification layer.

- Graph Construction & Label Propagation:

- Construct a nearest-neighbor graph from all the descriptor vectors.

- Compute a symmetric affinity matrix ((A)) for this graph.