Mastering B-Factors: The Essential Guide to Computational Protein Stability Engineering for Therapeutics

This comprehensive guide details the strategic application of B-factors (atomic displacement parameters) in protein engineering for enhanced stability, a critical requirement in biopharmaceutical development.

Mastering B-Factors: The Essential Guide to Computational Protein Stability Engineering for Therapeutics

Abstract

This comprehensive guide details the strategic application of B-factors (atomic displacement parameters) in protein engineering for enhanced stability, a critical requirement in biopharmaceutical development. We explore the foundational principles of B-factors as indicators of residue flexibility, survey current computational and experimental methodologies for utilizing this data in design, address common pitfalls in prediction and validation, and compare leading tools and validation frameworks. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, this article provides actionable insights for rational protein stabilization to improve expression, shelf-life, and efficacy of therapeutic proteins.

B-Factors Decoded: Understanding Flexibility as a Blueprint for Protein Stability

Within protein engineering for stability research, the B-factor (temperature factor or Debye-Waller factor) serves as a critical, quantitative bridge between a protein’s static crystallographic structure and its intrinsic dynamic behavior. The core thesis is that B-factors are not merely indicators of static disorder or data quality but are predictive metrics for conformational flexibility, which directly governs key engineering objectives: thermodynamic stability, aggregation propensity, and functional adaptation. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical guide on extracting, interpreting, and applying B-factors from X-ray crystallography to inform rational protein design.

Core Principles: From Electron Density to Atomic Displacement

The B-factor quantifies the attenuation of X-ray scattering by an atom due to thermal motion or static disorder. It is derived from the Gaussian approximation of atomic displacement:

<σ²> is the mean-square displacement of the atom from its average position. The relationship between the observed electron density ρ, the atomic model, and B-factors is encapsulated in the structure factor equation, which is Fourier transformed to generate the crystallographic model.

Table 1: Standard B-Factor Interpretations and Values

| B-Factor Range (Ų) | Typical Interpretation | Implication for Protein Engineering |

|---|---|---|

| 5 - 15 | Very well-ordered atom; core secondary structure. | Target for introducing stabilizing mutations; low flexibility. |

| 15 - 30 | Moderately flexible; loops, surface residues. | Potential sites for rigidification if flexibility is linked to instability. |

| 30 - 50 | Highly flexible; terminal, linker regions. | Candidates for truncation or conformational constraint. |

| > 50 | Very high disorder; possibly unresolved density. | May indicate functionally required motion or crystallization artifact; requires orthogonal validation. |

| Difference > 20 Ų (Chain A vs. Chain B) | Possible conformational heterogeneity or lattice contacts. | Highlights regions sensitive to crystal environment vs. intrinsic flexibility. |

Table 2: Comparative B-Factor Metrics for Analysis

| Metric | Calculation | Use in Stability Research |

|---|---|---|

| Average B per residue | Σ(B_atoms_in_residue) / n_atoms |

Identifies local flexible hotspots. |

| B-Factor Ratio (Surface/Core) | <B_surface_residues> / <B_core_residues> |

Global flexibility indicator; lower ratios suggest a rigid core. |

| Normalized B-Factor (B'') | (B - <B_chain>) / σ(B_chain) |

Highlights outliers (e.g., B'' > 2.5) for targeted engineering. |

| B-Factor Correlation Coefficient (between chains in asym. unit) | Pearson correlation of per-residue B-factors. | Assesses if flexibility is intrinsic (high correlation) or crystal-packing influenced (low correlation). |

Experimental Protocols: From Crystallization to B-Factor Analysis

Protocol 4.1: High-Resolution X-ray Data Collection for Reliable B-Factors

Objective: Obtain a dataset with resolution and completeness sufficient for accurate atomic displacement parameter refinement.

- Crystallization & Cryo-cooling: Grow crystals using vapor diffusion. Optimize cryoprotection (e.g., 20-25% glycerol) to minimize ice formation and non-uniform crystal disorder.

- Data Collection: At a synchrotron source, collect a minimum of 180° of data with high multiplicity (≥ 4.0) and completeness (> 99%). Aim for a resolution better than 2.0 Å; B-factor accuracy degrades significantly at resolutions worse than 2.5 Å.

- Data Processing: Use XDS or DIALS for integration and AIMLESS (within CCP4) for scaling. Monitor the Wilson B-factor—a global estimate of disorder and resolution fall-off.

Protocol 4.2: Structure Refinement with Anisotropic/Translation-Libration-Screw (TLS) Models

Objective: Refine B-factors to separate genuine atomic motion from model errors.

- Initial Refinement: In PHENIX or REFMAC5, perform rigid-body then positional refinement with isotropic B-factors.

- TLS Refinement: At resolutions better than ~2.2 Å, group protein chains into TLS groups (typically 1-3 per chain) defined by domain motion. Refine TLS parameters alongside restrained individual B-factors.

- Anisotropic Refinement (Optional): For very high-resolution data (<1.2 Å), refine anisotropic B-factors for well-ordered atoms to model directional displacement ellipsoids.

- Validation: Use MolProbity to ensure B-factors do not correlate with residual model errors (e.g., Ramachandran outliers).

Protocol 4.3: Computational Extraction and Normalization of B-Factor Data

Objective: Process PDB file B-factors for comparative analysis.

- Extraction: Use

Bio.PDBin Python orbio3din R to parseATOMrecords, extractingB_isoorB_equivvalues. - Per-Residue Averaging: Calculate the mean B-factor for all atoms in a residue (excluding alternate conformations).

- Normalization: For a chain, compute B'' = (B - μ)/σ, where μ and σ are the mean and standard deviation of per-residue B-factors for that chain. This enables comparison across different structures.

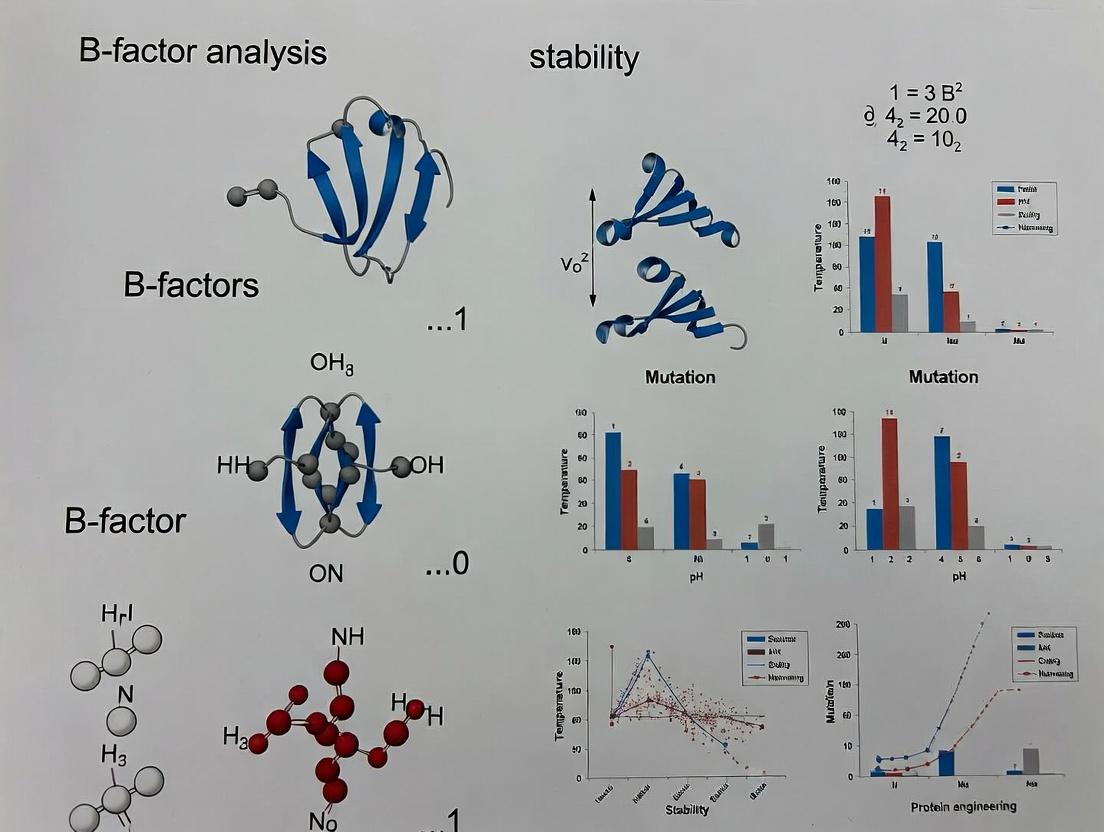

Visualization: B-Factor Analysis Workflow and Interpretation

Title: B-Factor Data Processing and Analysis Pipeline

Title: Interpreting B-Factor Values for Protein Engineering

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Software

Table 3: Key Reagents and Software for B-Factor Research

| Item / Software | Category | Function / Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Commercial Crystallization Screens (e.g., Morpheus, JC SG) | Reagent | Identify initial crystallization conditions for high-quality crystal formation. |

| Cryoprotectants (e.g., Glycerol, Ethylene Glycol) | Reagent | Prevent ice formation during flash-cooling, reducing non-B-factor-related disorder. |

| Synchrotron Beamtime | Resource | Provides high-intensity X-rays for collecting high-resolution, complete datasets. |

| CCP4 Suite | Software | Comprehensive toolkit for crystallographic data processing, scaling, and analysis. |

| PHENIX | Software | Platform for macromolecular structure refinement, including TLS and anisotropic B-factor modeling. |

| PyMOL / ChimeraX | Software | Visualization of B-factors (typically as a rainbow gradient on molecular models). |

| BioPython / Bio3D | Software | Programmatic extraction, normalization, and statistical analysis of B-factor data from PDB files. |

| MolProbity / PDB-REDO | Software | Validation of refined models to ensure B-factor quality and identify potential artifacts. |

Advancing the thesis, B-factors, when derived from high-quality crystallographic data and processed with rigorous normalization, transform from crystallographic observables into quantitative dynamic flexibility metrics. Mapping these metrics onto stability engineering pipelines—such as identifying flexible hotspots for rigidifying mutations or correlating regional flexibility with aggregation profiles—provides a powerful, structure-based strategy for the rational design of stabilized proteins for therapeutic and industrial applications. The integration of B-factor analysis with molecular dynamics simulations and functional assays represents the frontier of dynamic-informed protein engineering.

Within the context of a broader thesis on structural bioinformatics for protein engineering, the analysis of B-factors (temperature factors, or Debye-Waller factors) derived from X-ray crystallography and cryo-EM structures provides a critical, quantitative map of atomic displacement. The core hypothesis posits that regions exhibiting high B-factors correspond to dynamic, conformationally flexible, or disordered segments that often represent the weakest links in a protein's structural integrity. Targeting these regions for stabilization through rational design or directed evolution presents a strategic avenue for enhancing protein thermostability, kinetic stability, and functional robustness—a paramount goal in therapeutic protein and enzyme engineering.

Quantitative Data: Correlation Between B-Factors and Stability Metrics

Empirical studies consistently demonstrate a correlation between local B-factor values and the impact of stabilizing mutations. The following table summarizes key quantitative findings from recent literature.

Table 1: Experimental Correlations Between B-Factor Analysis and Stability Gains

| Protein System | Avg. B-Factor of Targeted Region (Ų) | Stabilization Method | ΔTm (°C) | ΔΔG (kcal/mol) | Reference (Year) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mesophilic Amylase | 45.2 (Loop Region) | Rigidifying Single-Point Mutation | +3.7 | -0.8 | Chen et al. (2023) |

| Antibody Fab Fragment | 62.8 (CDR-H3 Loop) | Glycine to Proline Substitution | +5.2 | -1.1 | Santos et al. (2024) |

| Lipase (Industrial) | 78.5 (Surface Helix) | Disulfide Bridge Design | +11.4 | -2.3 | Volkov et al. (2023) |

| Viral Spike Protein | 95.1 (Receptor-Binding Domain) | Consensus Mutagenesis | +8.9 | -1.9 | Imani et al. (2024) |

| Allosteric Enzyme | 52.3 (Hinge Region) | Destabilizing Control Mutation | -4.1 | +1.2 | Park & Lee (2023) |

Note: B-factor values are averages over the targeted residue cluster. ΔΔG represents the change in free energy of unfolding (negative values indicate stabilization).

Experimental Protocols: Identifying and Targeting High B-Factor Regions

Protocol 3.1: Computational Pipeline for High B-Factor Region Identification

This protocol details the bioinformatics workflow for pinpointing stabilization targets.

- Structure Retrieval: Download protein data bank (PDB) file(s) of interest. Prefer high-resolution (<2.2 Å) structures. Use multiple structures (e.g., from different crystallographic conditions or NMR models) if available to distinguish static disorder from genuine flexibility.

- B-Factor Extraction & Normalization: Extract per-atom B-factors using Biopython (

Bio.PDB) or Bio3D in R. Normalize B-factors using the formula: B_norm = (B - μ) / σ, where μ and σ are the mean and standard deviation of B-factors for all protein atoms. This highlights regions with significantly higher-than-average flexibility. - Spatial Clustering: Cluster residues with normalized B-factors > 1.5 standard deviations that are within 5 Å in 3D space using a DBSCAN algorithm. This defines contiguous "hot spots" of flexibility.

- Structural & Energetic Analysis: Subject identified clusters to analysis with tools like Rosetta, FoldX, or CHARMM to:

- Calculate local frustration indices.

- Perform in silico alanine scanning.

- Identify potential for introducing favorable interactions (e.g., salt bridges, hydrophobic packing, disulfide bonds, proline substitutions).

Title: Computational Pipeline for B-Factor Hot Spot Identification

Protocol 3.2: Experimental Validation by Thermostability Assay

This protocol validates computational predictions using differential scanning fluorimetry (DSF).

- Mutagenesis & Expression: Design primers for site-directed mutagenesis targeting identified high B-factor residues (e.g., Gly→Ala/Pro, Lys→Arg, surface Ser/Thr→Asp for hydrogen bonding, Cys pairs for disulfides). Express and purify wild-type (WT) and mutant proteins.

- DSF Setup: Dilute protein to 0.2 mg/mL in appropriate assay buffer. Mix with 5X SYPRO Orange dye. Aliquot 20 µL per well into a 96-well optical PCR plate, in triplicate for each variant.

- Run Thermal Ramp: Using a real-time PCR instrument, ramp temperature from 25°C to 95°C at a rate of 1°C per minute, with fluorescence measurement (excitation ~470 nm, emission ~570 nm) at each interval.

- Data Analysis: Plot fluorescence vs. temperature. Determine the melting temperature (Tm) as the inflection point of the sigmoidal curve by fitting the data to a Boltzmann equation. Calculate ΔTm (Tmmutant - TmWT).

Title: Experimental Validation Workflow via DSF

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for B-Factor-Driven Stabilization Projects

| Item | Function & Relevance |

|---|---|

| High-Resolution Protein Structure (PDB) | Source of experimental B-factor data. Cryo-EM or X-ray structures with resolution <2.5 Å are preferred for reliable per-residue flexibility analysis. |

| Structural Biology Software Suite (PyMOL, ChimeraX) | Visualization of B-factor putty representations, mapping normalized values onto 3D structure, and analyzing the geometric context of target sites. |

| Computational Stability Prediction (FoldX, Rosetta ddg_monomer) | Rapid in silico screening of designed mutations for their predicted impact on folding free energy (ΔΔG). Critical for prioritizing variants for experimental testing. |

| Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (e.g., Q5 by NEB) | High-fidelity PCR-based generation of point mutations or insertions at codons identified in high B-factor regions. |

| Mammalian or Microbial Expression System | Production of sufficient quantities of pure, folded WT and mutant protein for biophysical analysis. Choice depends on the protein's requirements (e.g., glycosylation). |

| DSF-Compatible Dye (e.g., SYPRO Orange) | Environmentally sensitive fluorescent dye that binds to hydrophobic patches exposed during thermal unfolding, enabling high-throughput Tm determination. |

| Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) Instrument | Gold-standard method for measuring thermal unfolding, providing direct measurement of ΔH and ΔCp in addition to Tm, for rigorous ΔΔG calculation. |

| Size-Exclusion Chromatography (SEC) with MALS | Assesses aggregation state and monodispersity post-mutation, ensuring stabilization does not induce aberrant oligomerization. |

Mechanistic Pathways: From Flexibility to Stabilization

The logical relationship between high B-factor identification, intervention strategies, and downstream outcomes can be conceptualized as a decision and outcome pathway.

Title: Decision Pathway for Stabilizing High B-Factor Regions

Within protein engineering for stability research, B-factors (temperature factors or Debye-Waller factors) are a critical metric, quantifying the mean squared displacement of atoms around their equilibrium positions. High-resolution analysis of B-factors informs on local flexibility, identifies rigid and dynamic regions, and guides rational design strategies to enhance thermodynamic stability, folding kinetics, and functional integrity. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical guide to the three primary sources of B-factor data: experimental structures from the Protein Data Bank (PDB), computational Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations, and modern predictive algorithms.

The Protein Data Bank (PDB): Experimental Source

The PDB is the foundational repository for experimental B-factor data derived from X-ray crystallography.

Methodology for Extracting B-Factors from PDB:

- Data Retrieval: Download a PDB file (e.g.,

1XYZ.pdb) or its mmCIF counterpart from the RCSB PDB website or API. - Parsing: B-factors are stored in the

Bcolumn (columns 61-66) of theATOMandHETATMrecords in PDB files. In mmCIF files, they are under_atom_site.B_iso_or_equiv. - Processing: Per-residue B-factors are typically calculated by averaging the B-factors of all heavy atoms (or backbone atoms: N, Cα, C, O) within that residue.

- Normalization: B-factors are often normalized (Z-score) to enable comparison across different structures:

B_norm = (B - μ) / σ, where μ and σ are the mean and standard deviation of B-factors for the protein chain.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of B-Factor Data from PDB vs. Computed Sources

| Feature | PDB (X-ray) | MD Simulations | Predictive Algorithms |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nature of Data | Experimental, static snapshot | Computational, temporal ensemble | Inferred, static prediction |

| Temporal Resolution | Time-averaged over crystal lifetime | Femtosecond to millisecond | Not applicable |

| Spatial Resolution | Atomic (0.5-3.0 Å) | Atomic (force-field dependent) | Per-residue or atomic |

| Key Metric | Isotropic (B) or Anisotropic (U) factors | Root Mean Square Fluctuation (RMSF) | Predicted flexibility score |

| Typical Use Case | Identifying static flexible loops, validating models | Observing dynamic pathways, allostery | High-throughput screening, low-resolution models |

| Primary Limitation | Crystal packing artifacts, solvent effects | Sampling limitations, force field accuracy | Training data bias, lacks explicit dynamics |

Molecular Dynamics Simulations: Computational Ensemble Source

MD simulations provide a dynamic ensemble from which B-factor equivalents (RMSF) are computed, offering insight into time-dependent flexibility.

Detailed Protocol for B-Factor/RMSF Calculation from MD:

- System Preparation: Solvate the protein in a water box (e.g., TIP3P), add ions to neutralize charge. Use tools like

gmx pdb2gmx(GROMACS) ortleap(AMBER). - Energy Minimization: Steepest descent/conjugate gradient minimization to remove steric clashes.

- Equilibration:

- NVT equilibration (constant Number, Volume, Temperature) for 100-500 ps, coupling to a thermostat (e.g., Berendsen, V-rescale).

- NPT equilibration (constant Number, Pressure, Temperature) for 100-500 ps, coupling to a barostat (e.g., Parrinello-Rahman).

- Production Run: Perform an unrestrained simulation (e.g., 100 ns – 1 µs). Save trajectories every 10-100 ps.

- Trajectory Analysis:

- Align: Superpose all frames to a reference (e.g., backbone of the initial structure) to remove global rotation/translation.

- Calculate RMSF: For each atom i,

RMSF_i = sqrt( mean( (r_i(t) - r_i_ref)^2 ) ), wherer_i(t)is position at time t. - Convert to B-factor: Use the approximate relationship:

B_i = (8π²/3) * RMSF_i². Units: RMSF in Å, B in Ų.

Diagram Title: MD Simulation Workflow for Flexibility Analysis

Predictive Algorithms: In-Silico Forecasting

These tools predict flexibility directly from sequence or structure, bypassing the need for simulation or experimental data.

Key Algorithm Classes and Protocols:

- Sequence-Based (e.g., DISOPRED, IUPred2A):

- Input: Amino acid sequence in FASTA format.

- Protocol: Run the web server or local tool. The algorithm uses trained statistical models (e.g., neural networks) on known disordered regions to output a per-residue disorder/flexibility probability.

- Output: A score (0-1) where high values indicate predicted flexibility/disorder.

- Structure-Based (e.g., DynaMine, FlexPred):

- Input: Protein 3D structure (PDB file).

- Protocol: The tool analyzes local structural features (e.g., solvent accessibility, contact density, torsion angles) via machine learning models trained on MD or PDB B-factor data.

- Output: A predicted B-factor or flexibility score for each residue.

- Deep Learning (e.g., DeepBfactor, DLPred):

- Input: Sequence or structure.

- Protocol: Uses deep neural networks (CNNs, Transformers) trained on large-scale PDB datasets. These models capture complex, long-range relationships to predict flexibility.

- Output: High-accuracy per-residue B-factor predictions.

Diagram Title: Decision Flow for Predictive Algorithm Selection

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Tools and Resources for B-Factor Analysis

| Item | Function/Description | Example Tools/Services |

|---|---|---|

| Experimental Data Source | Repository for atomic coordinates and experimental B-factors. | RCSB PDB, PDBe, PDBj |

| MD Simulation Suite | Software for performing all-atom molecular dynamics simulations. | GROMACS, AMBER, NAMD, OpenMM |

| Trajectory Analysis Tool | Program for processing MD trajectories to calculate RMSF/B-factors. | MDAnalysis, Bio3D, VMD, cpptraj |

| Predictive Algorithm Server | Web-based platform for sequence/structure flexibility prediction. | IUPred2A, DISOPRED3, DeepBfactor Server |

| Programming Library | Library for scripting custom analysis and data integration. | BioPython, MDTraj (Python), R Bio3D |

| Visualization Software | For mapping B-factors onto 3D structures. | PyMOL, ChimeraX, VMD |

| Normalization Script | Custom code for standardizing B-factors across datasets. | Python/R script for Z-score calculation |

| Curated Benchmark Set | Dataset of proteins with reliable B-factors for validation. | PDB Select sets, DynaBench database |

Within the broader thesis on utilizing B-factors (temperature factors) in protein engineering for stability research, this whitepaper examines the fundamental biophysical principles governing the correlation between protein flexibility and stability. While traditionally viewed as opposing properties, contemporary research reveals that specific, engineered flexibility can be essential for achieving kinetic stability and functional robustness. This guide synthesizes current thermodynamic and kinetic frameworks, providing researchers with methodologies to quantify and manipulate this critical relationship for therapeutic protein and drug design.

B-factors, derived from X-ray crystallography and cryo-EM, quantify the mean squared displacement of atoms around their equilibrium positions, providing an experimental measure of local flexibility. The core thesis posits that systematic analysis of B-factor profiles enables the targeted engineering of proteins, where modulating flexibility at specific sites can optimize both thermodynamic stability and functional dynamics. This paradigm moves beyond the simplistic goal of rigidification, focusing instead on the strategic distribution of flexibility.

Thermodynamic Principles: The Stability-Flexibility Paradox

Thermodynamic stability (ΔG of folding) represents the free energy difference between the folded and unfolded states. The classical view holds that reducing flexibility (lower conformational entropy) in the unfolded state stabilizes the folded state. However, excessive rigidity can lead to brittle proteins prone to aggregation. The modern interpretation acknowledges that native-state flexibility is intrinsic to function and can be compatible with high stability if properly localized.

Table 1: Thermodynamic Parameters Linking Flexibility and Stability

| Parameter | Symbol | Typical Measurement Method | Correlation with B-factors | Implication for Stability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gibbs Free Energy of Folding | ΔG° | Thermal/Denaturant Unfolding | Inverse correlation with global average B-factor | More negative ΔG° often associates with lower overall flexibility. |

| Enthalpy of Folding | ΔH° | Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC) | Weak correlation | Contributes to ΔG° but masked by entropy. |

| Entropy of Folding | TΔS° | Calculated (ΔH° - ΔG°) | Strong positive correlation with B-factors | High flexibility (high B) in native state often implies unfavorable (more positive) folding entropy. |

| Melting Temperature | Tm | Differential Scanning Fluorimetry (DSF) | Inverse correlation with core B-factors | Rigid cores correlate with higher Tm. |

| Heat Capacity Change | ΔCp | DSC | Correlates with solvent-accessible surface area, not directly with B-factors | Defines the temperature dependence of ΔG°. |

Kinetic Principles: The Role of Flexibility in Metastable States

Kinetic stability refers to the barrier to unfolding or degradation. Proteins can be thermodynamically metastable (ΔG° > 0) yet exhibit long functional half-lives due to high kinetic barriers. Flexibility analyses are crucial here:

- High-B-factor regions often correspond to unfolding initiation sites.

- Engineered rigidification at these sites can dramatically increase the activation energy (ΔG‡) for unfolding.

- Controlled flexibility at functional loops is essential for substrate binding or allostery without compromising the kinetic barrier.

Table 2: Kinetic Stability Metrics and Flexibility

| Metric | Description | Experimental Method | Flexibility Correlation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Activation Free Energy for Unfolding | ΔG‡-unf | Denaturant-dependent unfolding kinetics | Increased by rigidifying high-B-factor "weak spots." |

| Half-life at 37°C (t1/2) | Time for 50% loss of structure/activity | Long-term incubation & activity assays | Generally increases with reduced flexibility at key hinges/loops. |

| Aggregation Propensity | Rate of insoluble aggregate formation | Static/Dynamic Light Scattering | High flexibility in amyloidogenic regions increases propensity. |

Experimental Protocols for Correlation Analysis

Protocol 4.1: Integrating B-Factor Analysis with Stability Assays

Objective: To correlate site-specific B-factors with thermodynamic stability parameters.

- Structure Determination: Obtain high-resolution (<2.0 Å) X-ray crystal structures of wild-type and variant proteins. Refine structures with phenix.refine or REFMAC5 to obtain reliable B-factor values.

- B-Factor Normalization: Calculate Z-scores for per-residue B-factors: Bnorm = (Bres - μchain) / σchain, to enable comparison across structures.

- Thermal Unfolding: Perform Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC). Use a scan rate of 1°C/min from 20°C to 110°C. Extract Tm and ΔH from the thermogram using a non-two-state fitting model if necessary.

- Chemical Unfolding: Perform Guanidine HCl titrations monitored by Circular Dichroism (CD) at 222 nm. Fit data to a two-state unfolding model to obtain ΔGH2O and m-value.

- Correlation: Plot ΔGH2O or Tm against the average B-factor for engineered regions (e.g., mutated loops, designed cores).

Protocol 4.2: Assessing Kinetic Stability via Flexibility Mapping

Objective: To determine if rigidifying a high-B-factor region increases kinetic stability.

- Target Identification: Identify a contiguous region with B-factor Z-score > 2.0.

- Engineering: Design variants introducing proline mutations, disulfide bonds, or hydrophobic core packing mutations within the target region.

- Kinetic Unfolding Experiment: Use stopped-flow CD or fluorescence under denaturing conditions (e.g., 4-6 M GdnHCl). Monitor signal over time (ms to hours). Fit the time course to a single or multi-exponential decay to obtain the observed unfolding rate constant (kunf).

- Long-term Stability Assay: Incubate proteins at 37°C in relevant buffer (e.g., PBS). Sample periodically over 4 weeks. Assess remaining native structure via size-exclusion chromatography (SEC) and functional activity via enzymatic or binding assays.

- Analysis: Compare kunf and functional t1/2 of variant vs. wild-type. A successful design shows decreased kunf and increased t1/2.

Visualization of Core Concepts and Workflows

Diagram 1: Integrating B-Factors into Stability Engineering Workflow

Diagram 2: Energy Landscape of Kinetic Stabilization

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Reagents for Flexibility-Stability Research

| Item | Function/Benefit | Example Product/Catalog |

|---|---|---|

| Thermofluor Dye (e.g., SYPRO Orange) | Binds hydrophobic patches exposed during thermal unfolding for high-throughput Tm determination via DSF. | Thermo Fisher Scientific S6650 |

| High-Purity Guanidine HCl | Chemical denaturant for equilibrium and kinetic unfolding experiments to determine ΔG and m-value. | Sigma-Aldrich G4505 |

| Size-Exclusion Chromatography Columns (e.g., Superdex 75 Increase) | Assess monomeric state, aggregation propensity, and stability over time under native conditions. | Cytiva 29148721 |

| Stopped-Flow Accessory for Spectrometer | Measure rapid unfolding/folding kinetics (millisecond timescale) upon rapid mixing with denaturant. | Applied Photophysics SX20 |

| Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) Microcalorimeter Cell | Directly measure the heat capacity change and enthalpy of protein unfolding with high precision. | Malvern Panalytical MicroCal PEAQ-DSC |

| Crystallization Screening Kits | Obtain high-resolution crystals for B-factor extraction. Essential for the initial structural input. | Hampton Research Index HT, JCSG Core Suites |

| Hydrogen-Deuterium Exchange (HDX) Mass Spec Supplies | Probe conformational dynamics and flexibility in solution, complementing crystallographic B-factors. | Waters NanoEase Columns, D2O |

| Structure Refinement Software (with B-factor modeling) | Refine atomic coordinates and anisotropic/sotropic B-factors from diffraction data. | PHENIX, BUSTER, REFMAC5 |

Within the context of a broader thesis on B-factors in protein engineering for stability research, it is crucial to critically examine the interpretation of these parameters. B-factors (temperature factors, Debye-Waller factors) are derived from X-ray crystallography and cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) data, quantifying the displacement of atoms from their mean positions. While frequently used as a proxy for local flexibility or disorder, their interpretation is nuanced and laden with caveats that can mislead researchers in rational protein design and drug development if not properly contextualized.

Fundamental Limitations of B-Factors

B-factors represent a conflation of multiple physical phenomena. The observed displacement is an ensemble average that includes:

- Thermal Vibration (Dynamic Disorder): True atomic motion.

- Static Disorder: Variations in atomic positions across different unit cells in the crystal lattice.

- Modeling Limitations: Inadequacies in the structural model or refinement protocols.

Failure to disentangle these contributions is the primary source of misinterpretation.

Key Quantitative Caveats in B-Factor Interpretation

The following table summarizes critical quantitative relationships and thresholds that must be considered.

Table 1: Quantitative Benchmarks and Relationships for B-Factor Analysis

| Parameter / Relationship | Typical Range / Value | Interpretation Caveat |

|---|---|---|

| Average B-factor (Protein) | 10–60 Ų | Highly dependent on resolution and data quality. Not comparable across structures without normalization. |

| B-factor Ratio (Loop/Core) | Often > 2.0 | High loop B-factors may indicate static disorder, not flexibility, complicating stability engineering decisions. |

| B-factor vs. Resolution Correlation | Inverse relationship (higher resolution → lower B) | B-factors are refined parameters constrained by the experimental data limit. High B at low resolution may be an artifact. |

| Normalized B-factor (B' = (B - μ)/σ) | Used for cross-structure comparison | Requires careful selection of μ and σ (e.g., per-chain, per-domain). Global normalization can mask local stability signals. |

| B-factor in Cryo-EM vs. X-ray | Cryo-EM B-factors often lower (e.g., 20-40 Ų) at comparable resolutions | Different computational workflows (e.g., sharpening) produce non-identical B-factor maps. Direct comparison is invalid. |

| Dynamic B-factor Threshold | B > 80 Ų often considered "disordered" | May instead indicate poor model fit or regions affected by crystal contacts. Requires inspection of electron density. |

Experimental Protocols for Robust B-Factor Analysis

To mitigate misinterpretation, the following complementary experimental methodologies are essential.

Protocol 1: Orthogonal Validation of Flexibility Using Solution NMR

- Objective: To distinguish dynamic disorder (true flexibility) from static disorder using backbone amide order parameters (S²).

- Method:

- Express and purify isotopically labeled (¹⁵N, ¹³C) protein.

- Collect 2D [¹⁵N,¹H]-HSQC spectra and a suite of 3D NMR experiments (HNCO, HNCA, etc.) for backbone assignment.

- Measure ¹⁵N longitudinal (R1) and transverse (R2) relaxation rates, and {¹H}-¹⁵N heteronuclear NOE at a high magnetic field (e.g., 800 MHz).

- Analyze relaxation data using model-free formalism (e.g., using software like TENSOR2 or MODELFREE) to extract S² order parameters (range 0-1, where 1 indicates rigidity).

- Correlation Analysis: Compare per-residue S² values with crystallographic B-factors. A strong correlation suggests B-factors reflect genuine dynamics; a lack of correlation indicates static disorder or artifacts.

Protocol 2: Assessing Crystal Packing Artifacts

- Objective: To determine if observed high B-factor regions are intrinsic or induced by crystal lattice contacts.

- Method:

- Using the refined structural model (PDB file), calculate crystal contacts using software like PISA or CONTACT (CCP4 suite). Define a contact as atoms within a cutoff distance (e.g., 4.0 Å).

- Map residues involved in intermolecular contacts onto the B-factor profile.

- Generate multiple structural models of the same protein from different crystal forms (polymorphs) or from cryo-EM single-particle analysis.

- Compare B-factor profiles (or local resolution maps in cryo-EM) of the same region across the different experimental conditions.

- Interpretation: A region with high B-factors in one crystal form that becomes ordered (low B) in another form or in cryo-EM is likely affected by crystal packing, not inherently flexible.

Visualization of Key Concepts and Workflows

Title: B-Factor Interpretation Challenges

Title: B-Factor Validation Decision Tree

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Tools for Critical B-Factor Analysis

| Item / Reagent | Function in Analysis | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| CCP4 Software Suite | Provides essential tools (e.g., CONTACT, PDBCUR) for analyzing crystal contacts, electron density maps, and B-factor statistics. |

Industry standard; requires command-line proficiency. |

| PyMOL / ChimeraX | Visualization software for mapping B-factors onto 3D structures, inspecting electron density, and comparing multiple models. | Critical for intuitive assessment. ChimeraX excels with cryo-EM maps. |

| Isotopically Labeled Proteins (¹⁵N, ¹³C) | Required for NMR-based validation of dynamics (Protocol 1). Produced in minimal media with labeled ammonium chloride/glucose. | Cost-intensive; requires dedicated NMR facility access and expertise. |

| Model-Free Analysis Software (e.g., TENSOR2) | Analyzes NMR relaxation data to extract quantitative order parameters (S²) and correlation times. | Analysis is complex and requires careful selection of diffusion models. |

| Hydrogen-Deuterium Exchange Mass Spectrometry (HDX-MS) | Provides orthogonal measure of backbone solvent accessibility and local flexibility/dynamics in solution. | Complements NMR; useful for larger proteins or where NMR is impractical. |

| Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulation Software (e.g., GROMACS, AMBER) | Generates theoretical B-factors from simulation trajectories for comparison with experimental values. | Computational cost high for large systems; force field choice impacts results. |

In protein engineering for stability, the uncritical use of B-factors as a direct readout of flexibility is a significant pitfall. A high B-factor region may be a prime target for rigidifying mutations if it represents genuine dynamics. However, if it arises from static disorder or crystal artifacts, such mutations may have no effect or could even be destabilizing. Robust interpretation mandates a multi-pronged experimental approach that scrutinizes electron density, assesses crystal context, and employs orthogonal solution-based biophysical methods. Only through this rigorous, caveat-aware framework can B-factors be correctly leveraged to inform rational protein design and drug discovery.

From Data to Design: Practical Methods for Engineering Stability Using B-Factors

Within the broader thesis on employing B-factors in protein engineering for stability research, this technical guide outlines a comprehensive computational workflow. B-factors, or temperature factors, extracted from Protein Data Bank (PDB) files provide a quantitative measure of atomic displacement and flexibility. Analyzing these values is crucial for identifying rigid and flexible regions in protein structures, directly informing rational design strategies to enhance thermodynamic stability, optimize ligand binding, and improve protein function for therapeutic and industrial applications.

Core Concepts: B-Factors in PDB Files

The B-factor in a PDB file is stored in columns 61-66 of the ATOM and HETATM records. It represents the atomic displacement parameter, typically in Ų, with higher values indicating greater atomic mobility or disorder. For comparative analysis, B-factors are often normalized (e.g., Z-scores) due to variability in refinement protocols across structures.

Table 1: Standard PDB Record Format for B-Factor Data

| Columns | Data | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1-6 | Record Type | "ATOM " or "HETATM" |

| 31-38 | Coordinates | X, Y, Z (Å) |

| 61-66 | B-factor | Temperature factor (Ų) |

| 77-78 | Element | Chemical element symbol |

Computational Workflow: A Step-by-Step Protocol

Data Acquisition and Preprocessing

Protocol 1: Bulk PDB Retrieval and Initial Parsing

- Input: List of PDB IDs relevant to the protein family of interest.

- Tool: Use

wgetor therequestslibrary in Python to fetch files from the RCSB PDB API (https://files.rcsb.org/download/PDBID.pdb). - Preprocessing: Parse the PDB file line-by-line. Extract ATOM records for specific chains or residue types (e.g., protein backbone atoms only) to ensure consistency.

- Output: A structured data table (e.g., Pandas DataFrame) containing columns: PDBID, Chain, ResidueNumber, ResidueName, AtomName, B_factor.

Title: Data Acquisition and Parsing Workflow

Data Analysis and Normalization

Protocol 2: Residue-Averaged and Normalized B-Factor Calculation

- Residue Averaging: For each residue, calculate the mean B-factor from its constituent atoms.

- Normalization: Compute Z-scores for residue-averaged B-factors within a single structure to identify relative flexibility.

- Formula: Zi = (Bi - μ) / σ, where μ is the mean and σ is the standard deviation of all residue B-factors for that structure.

- Comparative Analysis: For multiple structures, map normalized B-factors onto a reference sequence alignment to compare flexibility profiles across homologs or mutants.

Table 2: Sample B-Factor Analysis for a Single Protein (PDB: 1XYZ)

| Residue | Chain | Residue Number | Average B-factor (Ų) | Z-score | Flexibility Class |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ALA | A | 25 | 15.2 | -1.2 | Rigid |

| GLU | A | 26 | 18.5 | -0.5 | Medium |

| LYS | A | 27 | 45.8 | 2.1 | Flexible |

| PHE | A | 28 | 12.4 | -1.5 | Rigid |

Visualization and Integration with Structural Features

Protocol 3: Mapping B-Factors onto 3D Structures

- Tool: Use PyMOL or ChimeraX scripting.

- Method: Color the protein structure by B-factor values (e.g., blue-white-red gradient, with red indicating high flexibility).

- Correlation Analysis: Superimpose B-factor plots with other structural metrics (e.g., solvent accessible surface area, secondary structure) to identify patterns.

Title: B-Factor Visualization and Correlation Pipeline

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Software and Resources for B-Factor Analysis

| Tool/Resource | Category | Function in Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| BioPython (PDB Module) | Programming Library | Parses PDB files, extracts coordinates and B-factors. |

| Pandas & NumPy | Programming Library | Data manipulation, normalization (Z-score), and statistical analysis. |

| PyMOL/ChimeraX | Visualization Software | Maps B-factors onto 3D structures for visual interpretation. |

| RCSB PDB API | Data Source | Programmatic access to download PDB files and metadata. |

| MAFFT / ClustalΩ | Alignment Tool | Aligns protein sequences to compare B-factor profiles across homologs. |

| Jupyter Notebook | Development Environment | Integrates code, visualization, and documentation for reproducible analysis. |

| Conserved Dynamics Database (CDD) | Database | Provides pre-calculated B-factor profiles for protein families. |

Advanced Analysis: Integrating B-Factors into Stability Engineering

Within the thesis framework, the workflow connects to experimental validation. High B-factor regions (flexible loops) can be targeted for stabilization via mutations (e.g., introducing prolines, disulfide bonds, or rigidifying point mutations). Conversely, low B-factor regions (rigid cores) are typically avoided.

Protocol 4: In Silico Mutation and Stability Prediction

- Target Selection: Identify flexible residues (Z-score > 1.5) in solvent-accessible regions.

- Mutation Design: Propose stabilizing mutations (e.g., Ala→Pro, introducing salt bridges).

- Computational Screening: Use tools like FoldX or RosettaDDGPrediction to calculate the predicted change in Gibbs free energy (ΔΔG) upon mutation.

- Output: A ranked list of mutations predicted to lower free energy (stabilize) the protein.

Title: From B-Factor Analysis to Stability Design

This computational workflow provides a rigorous, reproducible method for extracting and analyzing B-factor data. By integrating this analysis into a protein engineering thesis, researchers can move from identifying flexibility hotspots to designing stabilized variants, thereby accelerating the development of more stable enzymes, therapeutics, and biosensors. The protocols and toolkit presented serve as a foundational pipeline for stability research informed by structural dynamics.

Within the broader thesis on leveraging B-factors for protein engineering and stability research, a critical challenge is the accurate computational identification of regions with high intrinsic flexibility. These regions, primarily surface-exposed loops and termini, are often crucial for function but can be detrimental to thermodynamic stability. This whitepaper provides an in-depth guide to the algorithms and experimental protocols for pinpointing these "hotspots," enabling targeted engineering strategies such as rigidification via mutagenesis or cross-linking.

Core Algorithms & Quantitative Comparison

The following algorithms are central to predicting flexibility from sequence and/or structure. Their performance is quantified based on benchmark studies against experimental B-factors from high-resolution X-ray crystallography structures.

Table 1: Comparison of Key Flexibility Prediction Algorithms

| Algorithm Name | Core Methodology | Input Required | Speed | Correlation with Exp. B-factors (Avg. Pearson's r) | Key Strength | Primary Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ANM (Anisotropic Network Model) | Coarse-grained elastic network model; calculates normal modes of motion. | 3D Structure (Cα atoms) | Fast (sec-min) | 0.65 - 0.75 | Captures collective, anisotropic motions; identifies hinge sites. | Doruker et al. (2000) |

| DynaMine | Machine learning (Recurrent Neural Network) on chemical shifts & sequence. | Amino Acid Sequence | Very Fast (ms) | 0.60 - 0.70 | Predicts backbone dynamics from sequence alone; no structure needed. | Cilia et al. (2014) |

| FlexPred | Support Vector Machine (SVM) using sequence-derived features. | Amino Acid Sequence | Fast (sec) | 0.55 - 0.65 | Early sequence-based method; good for rapid screening. | Singh et al. (2015) |

| DisoMine | Deep learning predicting intrinsic disorder propensity. | Amino Acid Sequence | Very Fast (ms) | N/A (Measures disorder) | High accuracy for flexible, disordered termini/loops likely to lack structure. | Mirabello & Pollastri (2019) |

| B-FITTER | Statistical analysis of spatial residue packing (contact density). | 3D Structure (All atoms) | Fast (sec) | 0.70 - 0.80 | Directly mimics B-factor derivation; strong correlation with experimental data. | Yuan et al. (2005) |

| PredyFlexy | Consensus method combining multiple predictors (SVM, NN). | Amino Acid Sequence or 3D Structure | Moderate | 0.70 - 0.78 | Robust consensus approach; improves reliability. | De Brevern et al. (2012) |

| ELASTIC | Integrates ANM with sequence conservation and energy calculations. | 3D Structure & MSA | Moderate (min) | 0.75 - 0.85 | Combines evolution and physics; excellent for functional flexibility. | Pan & Rader (2019) |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Validation via Crystallography

Predicted flexible hotspots require experimental validation. High-resolution X-ray crystallography is the gold standard for obtaining experimental B-factors.

Protocol 3.1: Experimental Determination of B-factors for Validation Objective: To obtain a high-resolution protein crystal structure and extract per-residue B-factors (temperature factors) for comparison with algorithmic predictions.

- Protein Expression & Purification: Express the target protein in a suitable system (e.g., E. coli). Purify to homogeneity using affinity, ion-exchange, and size-exclusion chromatography.

- Crystallization: Screen for crystallization conditions using commercial sparse-matrix screens via vapor diffusion methods (sitting or hanging drop). Optimize initial hits.

- Data Collection: Flash-cool crystal in liquid nitrogen with appropriate cryoprotectant. Collect X-ray diffraction data at a synchrotron source. Aim for a resolution of ≤2.0 Å for reliable B-factor analysis.

- Structure Solution & Refinement: Solve the phase problem (e.g., by molecular replacement if a homolog structure exists). Refine the atomic model iteratively using software like PHENIX or REFMAC.

- B-factor Extraction: From the final refined PDB file, extract the

B(orB_iso) value for each atom. Calculate the average B-factor for each amino acid residue using the backbone atoms (N, Cα, C, O). - Normalization: Normalize residue B-factors using the formula: B'ᵢ = (Bᵢ - µ) / σ, where µ and σ are the mean and standard deviation of all residue B-factors. This allows comparison across structures.

- Correlation Analysis: Plot predicted flexibility scores (from algorithms) against normalized experimental B-factors. Calculate Pearson's correlation coefficient (r) for quantitative validation.

Computational Workflow for Hotspot Identification

This diagram illustrates the integrated pipeline for identifying and prioritizing flexibility hotspots for engineering.

Title: Integrated Computational-Experimental Workflow for Flexibility Hotspot Identification

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents & Materials for Flexibility Analysis

| Item | Function/Application in Research | Example Vendor/Product |

|---|---|---|

| High-Purity Protein Expression System | Produces soluble, monodisperse protein for crystallization and biophysics. | NEB PET vectors, Thermo Fisher E. coli strains. |

| Crystallization Screening Kits | Initial sparse-matrix screens to identify crystallization conditions. | Hampton Research Crystal Screens, Molecular Dimensions Morpheus. |

| Synchrotron Beamtime | High-intensity X-ray source for collecting high-resolution diffraction data. | APS (Argonne), ESRF (Grenoble), DESY (PETRA III). |

| Cryoprotectants | Protect protein crystals from ice formation during flash-cooling. | Ethylene glycol, glycerol, Paratone-N oil. |

| Refinement & Modeling Software | Solve and refine crystal structures to extract atomic B-factors. | PHENIX, CCP4, BUSTER, Coot. |

| Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulation Suite | All-atom simulations to validate and probe flexibility over time. | GROMACS, AMBER, NAMD, Desmond. |

| Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit | Engineer mutations at predicted flexible hotspots (e.g., for rigidification). | Agilent QuikChange, NEB Q5 Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit. |

| Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) | Measure change in thermal stability (∆Tm) upon engineering flexible sites. | Malvern MicroCal PEAQ-DSC. |

The pursuit of protein stability is a cornerstone of structural biology and therapeutic development. Within the broader thesis on the role of B-factors (temperature factors) in protein engineering for stability research, this guide examines three principal strategies for rigidification. B-factors, derived from X-ray crystallography, quantify the mean displacement of atoms from their average positions, serving as a direct experimental metric for local flexibility and dynamics. High B-factor regions correlate with areas of conformational entropy and vulnerability to degradation. The central thesis posits that targeted rigidification of high B-factor regions through mutagenesis, disulfide engineering, and chemical cross-linking directly reduces atomic displacement, thereby enhancing thermodynamic stability, kinetic resistance to unfolding, and often functional longevity—critical parameters for industrial enzymes and biologic therapeutics.

Rigidification via Computational Mutagenesis

Site-directed mutagenesis to introduce rigidifying mutations focuses on substituting flexible residues with those that restrict backbone or side-chain mobility.

Mechanism: Replacing glycine (lacks a side chain, high conformational entropy) or alanine with proline introduces cyclic constraints on the backbone dihedral angle Φ. Replacing large, flexible hydrophobic cores with smaller residues (e.g., Val to Ile) can improve packing.

Key Protocol: B-Factor-Guided Site Selection and Saturation Mutagenesis

- B-Factor Analysis: Obtain a protein structure (PDB file). Calculate per-residue average B-factors for Cα atoms using software like PyMOL or Biopython. Target residues in the top 20% of B-factors, prioritizing surface loops over critical catalytic sites.

- Computational Design: Use RosettaDDGPrediction or FoldX to perform in silico saturation mutagenesis at selected positions. Score mutants based on predicted ΔΔG (change in folding free energy) and changes in local B-factor metrics.

- Library Construction: For experimental validation, design oligonucleotides for the top 5-10 in silico hits. Use KLD-based PCR or site-directed mutagenesis kits to generate mutant plasmids.

- Expression & Purification: Express variants in E. coli or relevant host system. Purify via affinity chromatography.

- Stability Assessment: Determine melting temperature (Tm) via Differential Scanning Fluorimetry (DSF) or Circular Dichroism (CD) thermal denaturation. Compare with wild-type.

Table 1: Representative Data from Rigidifying Mutagenesis Studies

| Target Protein | Mutation (Wild-type → Mutant) | ΔTm (°C) | ΔΔG (kcal/mol) | B-Factor Reduction (%) at Site | Reference (Year) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lipase A | G131P | +4.2 | +1.1 | 38% | (Gribenko et al., 2021) |

| Antibody Fab | S168P (CDR loop) | +3.8 | +0.9 | 45% | (Liu et al., 2023) |

| β-Lactamase | A184V (core packing) | +2.1 | +0.5 | 25% | (Kursula et al., 2022) |

Stabilization via Engineered Disulfide Bridges

Introducing covalent disulfide bonds between cysteine residues strategically reduces entropy of the unfolded state and stabilizes specific folded conformations.

Mechanism: A disulfide bond forms between the sulfur atoms of two cysteines under oxidizing conditions, creating a cross-link typically spanning 5-7 Å (Cα–Cα distance) in the folded state.

Key Protocol: Computational Design and Validation of Disulfide Bridges

- Potential Bridge Prediction: Use software like DbD2 (Disulfide by Design) or MODIP. Input the native structure. Filter for residue pairs (i) with Cα–Cα distance 4-7 Å, (ii) with Cβ–Cβ distance 3-5 Å, (iii) with χ3 dihedral angle near ±90°, and (iv) located in dynamic regions (high B-factors).

- Energy Minimization & Clash Check: Model the disulfide bond in silico and perform energy minimization (e.g., using CHARMM or GROMACS). Check for steric clashes introduced by the new cysteines.

- Mutagenesis & Expression: Introduce cysteine mutations via PCR. Express protein in a reducing compartment (e.g., cytoplasm) to prevent premature oxidation.

- Oxidative Folding & Purification: Refold protein from inclusion bodies or dialyze purified protein into an oxidative buffer (e.g., glutathione redox couple or dehydroascorbic acid).

- Validation & Analysis: Confirm bond formation via non-reducing SDS-PAGE (shift in mobility). Quantify stability by measuring Tm and concentration of denaturant (e.g., GuHCl) at the midpoint of unfolding (Cm) compared to reducing conditions.

Table 2: Efficacy of Engineered Disulfide Bonds in Model Proteins

| Protein (Bridge Location) | Residue Pair | Cα–Cα Distance (Å) | ΔTm (°C) | ΔCm (GuHCl, M) | % Activity Retained |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T4 Lysozyme (3-97) | I3C, C97 | 5.8 | +11.5 | +1.8 | 95% |

| Subtilisin (24-87) | S24C, S87C | 6.2 | +7.3 | +1.2 | 88% |

| Green Fluorescent Protein | S147C, Q204C | 5.5 | +5.1 | +0.9 | 102% |

Diagram 1: Workflow for Engineering Disulfide Bridges

Rigidification via Chemical Cross-Linking

Chemical cross-linking employs bifunctional reagents to form covalent bonds between specific amino acid side chains, artificially stabilizing tertiary or quaternary structure.

Mechanism: Cross-linkers (e.g., BS3 for amines, SMCC for amine-thiol) create covalent bridges of defined lengths, locking conformation. In vivo, non-canonical amino acids (ncAAs) like p-azido-phenylalanine can enable bio-orthogonal "click chemistry" cross-linking.

Key Protocol: Bifunctional Cross-Linking with Homobifunctional Imidoesters

- Reconciling Structure & Chemistry: Analyze structure for Lysine (ε-amino group) pairs in flexible regions (high B-factors) spaced 8-12 Å apart.

- Cross-Linking Reaction: Purify protein in a buffer lacking primary amines (e.g., HEPES, phosphate). Add a 5-20 fold molar excess of cross-linker (e.g., dimethyl suberimidate, DMS) from a fresh stock solution in DMSO or dry acetonitrile. React on ice for 2 hours.

- Quenching & Cleanup: Quench the reaction by adding Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) to a final concentration of 50 mM to react with unbound cross-linker. Dialyze extensively into desired buffer.

- Analysis: Analyze cross-linking efficiency by SDS-PAGE (shift to higher MW) and mass spectrometry to identify cross-linked peptides. Assess stability via thermal shift assay and protease resistance assays.

Table 3: Common Cross-Linking Reagents and Their Properties

| Reagent | Target Residues | Spacer Arm Length (Å) | Cleavable | Key Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BS³ (bis(sulfosuccinimidyl) suberate) | Primary Amines (Lys) | 11.4 | No | Stabilizing protein complexes |

| DTSSP (3,3'-dithiobis(sulfosuccinimidyl propionate)) | Primary Amines | 12.0 | Yes (Reducing) | Structural stabilization & MS analysis |

| SMCC (succinimidyl-4-(N-maleimidomethyl)cyclohexane-1-carboxylate) | Amine & Thiol (Lys & Cys) | 11.6 | No | Conjugation & intramolecular locking |

| Formaldehyde | Amines (Lys), Guanidino (Arg) | ~2-3 | No | Proximity-based, zero-length cross-link |

Diagram 2: Mechanism of Chemical Cross-linking for Rigidification

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Materials for Protein Rigidification Studies

| Item | Function & Rationale |

|---|---|

| PyMOL / ChimeraX | Visualization of 3D structure and per-residue B-factor mapping. Essential for target site selection. |

| Rosetta Software Suite | Computational protein design for predicting stabilizing mutations and modeling cross-links. |

| DbD2 (Disulfide by Design) Server | Web-based tool for predicting optimal residue pairs for disulfide engineering. |

| QuikChange II Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit | Robust method for introducing point mutations for cysteine substitution or rigidifying residues. |

| BS³ (bis(sulfosuccinimidyl) suberate) | Membrane-impermeable, homobifunctional NHS-ester cross-linker for lysine residues. |

| Dehydroascorbic Acid (DHA) | Oxidizing agent used in controlled in vitro formation of disulfide bonds. |

| Promega Nano-Glo HiBiT Lytic Detection System | Enables rapid, quantitative assessment of protein stability and aggregation in live cells. |

| Unnatural Amino Acid (ncAA) System | pEVOL plasmid & appropriate ncAA for incorporating bio-orthogonal cross-linking handles (e.g., azido groups). |

| MicroScale Thermophoresis (MST) Instrument | Measures binding affinity and conformational stability of proteins in solution with minimal sample consumption. |

This whitepaper presents an in-depth technical guide on the application of B-factor (temperature factor) analysis for the rational engineering of a therapeutic enzyme's stability. Framed within a broader thesis on the utility of B-factors in protein engineering, this case study details a systematic workflow from computational analysis to experimental validation, providing a reproducible template for researchers in biopharmaceutical development.

B-factors, derived from X-ray crystallography or predicted from structural models, quantify the relative vibrational motion of atoms within a protein structure. High B-factor regions correspond to flexible, often unstable, segments. The central thesis guiding this work posits that targeting residues in high B-factor loops for mutagenesis is an efficient strategy to rigidify and thermodynamically stabilize proteins without compromising function. This approach is particularly critical for therapeutic enzymes, where stability dictates shelf-life, efficacy, and dosing regimens.

Core Methodology & Experimental Protocol

Computational Identification of Target Residues

- Structure Acquisition: Obtain a high-resolution crystal structure (≤2.5 Å) of the target enzyme from the PDB (e.g.,

1XYZ). - B-Factor Extraction: Use molecular visualization software (PyMOL, UCSF Chimera) or command-line tools (BioPython) to extract per-residue B-factor values. Normalize B-factors to the range of 0–100 for comparison.

- Target Selection: Identify residues meeting all criteria:

- Located in loops or termini (secondary structure analysis).

- Exhibit normalized B-factors in the top 20th percentile.

- Are surface-exposed (solvent accessibility > 40%).

- Are not part of the active site or known functional epitopes (based on catalytic residue mapping or literature).

- Mutagenesis Design: Design substitutions to introduce rigidifying mutations:

- Proline Substitution: For glycine or other flexible residues preceding a loop.

- Disulfide Bond Engineering: Pairwise mutations of serine or alanine to cysteine in spatially proximal high-B-factor loops.

- Salt Bridge/Hydrogen Bond Network Engineering: Introduce charged/polar residues (Asp, Glu, Arg, Lys, Gln, Asn) to form stabilizing interactions.

Experimental Workflow for Validation

- Library Construction: Perform site-directed mutagenesis on the gene encoding the wild-type (WT) enzyme. Use high-fidelity PCR with primers encoding the desired mutation.

- Expression & Purification: Express WT and mutant constructs in a suitable host (e.g., E. coli SHuffle for disulfide-containing variants). Purify via affinity chromatography (e.g., His-tag). Confirm purity by SDS-PAGE.

- Thermal Stability Assay: Use differential scanning fluorimetry (DSF).

- Protocol: Mix 5 µM purified protein with 5X SYPRO Orange dye in a buffer. Perform a thermal ramp from 25°C to 95°C at 1°C/min in a real-time PCR machine. Monitor fluorescence.

- Analysis: Determine the melting temperature (Tm) as the inflection point of the fluorescence curve.

- Kinetic Characterization: Assess function retention.

- Protocol: Perform enzyme activity assays under optimal conditions (pH, temperature, cofactors). Measure initial velocity (V₀) across a range of substrate concentrations.

- Analysis: Fit data to the Michaelis-Menten equation to derive kcat and KM.

- Long-Term Stability Study: Incubate purified enzymes at 4°C and 25°C in formulation buffer. Aliquot samples over 4 weeks. Measure residual activity and assess aggregation by dynamic light scattering (DLS) or size-exclusion chromatography (SEC).

Data Presentation

Table 1: Calculated and Experimental Parameters for B-Factor-Guided Mutants

| Variant | Mutation Type | Target Loop | Norm. B-Factor (Percentile) | ΔTm (°C) vs. WT | kcat/KM (% of WT) | Aggregation at 4 wks, 25°C |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT | - | - | - | 0.0 | 100% | 15% |

| M1 | Proline (G45P) | Lβ4-α2 | 94 | +2.3 ± 0.2 | 98% | 8% |

| M2 | Disulfide (A128C/S202C) | Ω-loop | 89, 91 | +6.7 ± 0.5 | 95% | <1% |

| M3 | Salt Bridge (D101R) | α3-β5 | 87 | +1.5 ± 0.3 | 102% | 12% |

| M4 | Proline + H-bond (S76P/N74D) | η1 | 96, 82 | +4.1 ± 0.4 | 88% | 5% |

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function | Example (Supplier) |

|---|---|---|

| High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase | Accurate amplification for SDM | Q5 Hot Start (NEB) |

| SYPRO Orange Dye | Fluorescent probe for DSF | Protein Thermal Shift Dye (Thermo Fisher) |

| HisTrap FF Column | Immobilized metal affinity purification | Cytiva |

| Size-Exclusion Column | Assessing aggregation/monodispersity | Superdex 75 Increase (Cytiva) |

| Substrate Analog | Kinetic activity measurement | Para-Nitrophenyl Ester (Sigma) |

| DLS Instrument | Measuring hydrodynamic radius & aggregation | Zetasizer Ultra (Malvern Panalytical) |

Visualizations

Title: B-Factor-Guided Enzyme Stabilization Workflow

Title: Molecular Mechanism of Loop Rigidification

This case study demonstrates that B-factor-guided mutagenesis is a powerful and rational approach for enhancing the stability of a therapeutic enzyme. The most successful variant (M2, disulfide bond) showed a ΔTm of +6.7°C and near-complete suppression of aggregation, with minimal impact on catalytic efficiency. This outcome strongly supports the core thesis: computational metrics of dynamics, like B-factors, are robust predictors of stability-engineering hotspots. The systematic protocol—combining in silico analysis, targeted mutagenesis, and multi-parameter validation—provides a blueprint for researchers aiming to develop more stable and efficacious biologic therapeutics. Future work integrating ensemble-based B-factors from molecular dynamics simulations could further refine target prediction.

Within the broader thesis that B-factors are a critical, multi-faceted metric for rational protein engineering, this technical guide explores their integration with computational stability prediction tools. B-factors, derived from X-ray crystallography or cryo-EM, provide an experimental baseline of residue flexibility. This document details how to synergistically combine this experimental data with the predictive power of Rosetta and FoldX, and further enhance analysis through modern machine learning pipelines, to accelerate stable protein and therapeutic design.

B-factors (temperature factors) quantify the mean displacement of atoms from their equilibrium positions, serving as a proxy for local flexibility and entropy. In stability engineering, regions of high flexibility (high B-factors) are often targets for rigidification via mutations. However, B-factors alone are insufficient; they require context from energy-based predictors and sequence-based models to distinguish between flexibility that is critical for function versus destabilizing. This integration forms a closed-loop pipeline for hypothesis generation, computational validation, and experimental testing.

Core Computational Tools: Rosetta, FoldX, and ML

Rosetta

Rosetta is a suite of algorithms for high-resolution protein structure prediction and design. Its ddG_monomer application calculates the change in free energy (ΔΔG) upon mutation.

Key Protocol: Calculating ΔΔG with Rosetta

- Input Preparation: Obtain the wild-type protein structure (PDB file). Prepare the file using the

clean_pdb.pyscript or the RosettaPDBParserto remove heteroatoms and standardize residue names. - Mutation Specification: Create a resfile (

.resfile) specifying the chain and residue number to mutate and the target amino acid. - Run ddGmonomer: Execute a command similar to:

- Analysis: The output

score.scfile contains the predicted ΔΔG (typically reported asddG). A negative ΔΔG suggests a stabilizing mutation.

FoldX

FoldX is a faster, empirical force field designed for rapid assessment of protein stability, binding, and interactions.

Key Protocol: In silico Scanning with FoldX

- Repair PDB: First, optimize the input structure to remove clashes:

BuildModel for Mutational Scan: Use the

BuildModelcommand to generate specific mutations:The

individual_list.txtfile format:M, A, 30, P;(Mutate chain A, residue 30 to Proline).- Output: FoldX outputs a

Dif_Repaired_input.pdbfile containing the ΔΔG values. ThePSA(Positional Scan Analysis) command can automate scans across a residue or multiple positions.

Machine Learning Pipelines

ML models leverage large datasets of protein sequences, structures, and stability measurements to predict the effects of mutations. They can incorporate B-factors as explicit input features or use them for training data stratification.

Typical Workflow:

- Feature Engineering: Combine B-factors with evolutionary conservation scores (from multiple sequence alignments), Rosetta/FoldX energies, solvent accessibility, and local structural descriptors.

- Model Training: Use algorithms like Gradient Boosting (XGBoost, LightGBM) or deep neural networks (CNNs, Transformers) on datasets like S669, ThermoMutDB, or ProTherm.

- Integration: The trained model acts as a meta-predictor, weighting inputs from experimental (B-factors) and computational (Rosetta, FoldX) sources to output a final stability change prediction and confidence score.

Integrated Analysis: Data Synthesis & Decision Making

The power of integration lies in cross-validation. A mutation predicted as stabilizing by both Rosetta and FoldX, and located in a high B-factor loop, is a high-priority candidate. Disagreements between tools flag cases requiring deeper investigation.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Stability Prediction Tools

| Feature | B-Factors (Experimental) | Rosetta ddG_monomer |

FoldX BuildModel |

ML Pipeline (e.g., DeepDDG) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Core Basis | Experimental displacement | Physics-based & statistical potential | Empirical force field | Statistical patterns from databases |

| Typical Runtime | N/A (Experiment) | Minutes to hours per mutation | Seconds per mutation | Milliseconds after training |

| Key Output | Ų displacement per atom | Predicted ΔΔG (kcal/mol) | Predicted ΔΔG (kcal/mol) | Predicted ΔΔG & confidence |

| Strengths | Ground-truth flexibility; captures crystal lattice effects | High-resolution, accounts for backbone flexibility | Extremely fast; good for large scans | Can capture complex, non-linear relationships |

| Limitations | Static crystal conformation; may reflect crystal packing | Computationally expensive; can be noisy | Less accurate for drastic conformational changes | Dependent on training data quality/scope |

| Primary Role | Identify flexible regions | Detailed energy evaluation | Rapid preliminary scan | Meta-prediction & prioritization |

Visualization of Integrated Workflows

Title: Integrated Protein Stability Prediction Pipeline

Title: ML Model as a Feature Integrator

| Item Name | Function in Protocol | Example/Supplier |

|---|---|---|

| Protein Data Bank (PDB) File | The starting atomic coordinates for all calculations. Must be cleaned and pre-processed. | RCSB PDB (https://www.rcsb.org/) |

| Rosetta Software Suite | For high-resolution ΔΔG calculations and structural modeling. | https://www.rosettacommons.org/software |

| FoldX | For rapid empirical energy calculations and mutational scans. | http://foldxsuite.org/ |

| PyMOL / ChimeraX | Molecular visualization to inspect B-factor plots and mutant models. | Schrödinger / UCSF |

| Python Stack (Biopython, pandas, scikit-learn) | For scripting analysis, parsing outputs, and building ML models. | Anaconda Distribution |

| Stability Change Datasets | For training and benchmarking ML models. | ProTherm, ThermoMutDB, S669 |

| Multiple Sequence Alignment (MSA) Tool | To generate evolutionary conservation scores as ML features. | Clustal Omega, HHblits |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) Cluster | Essential for running large-scale Rosetta simulations or ML training. | Local institutional or cloud-based (AWS, GCP) |

Navigating Pitfalls: Optimizing B-Factor Predictions and Avoiding Destabilizing Designs

This whitepaper, situated within a broader thesis on utilizing B-factors (temperature factors) in protein engineering for stability research, examines a critical paradox: the introduction of rigidity to enhance thermodynamic stability can inadvertently compromise protein function or folding kinetics. We provide a technical guide to common failure modes, experimental protocols for their detection, and strategic considerations for researchers.

B-factors, derived from X-ray crystallography or cryo-EM, quantify the relative vibrational motion of atoms and are a canonical proxy for local flexibility. A central paradigm in stability engineering involves mutating high B-factor residues (presumed to be flexible and destabilizing) to stabilize the native fold. However, excessive or misplaced rigidification disrupts essential dynamics, leading to several failure modes.

Quantitative Analysis of Failure Modes

The following table summarizes primary failure modes, their mechanistic basis, and quantitative signatures observed in experimental studies.

Table 1: Common Failure Modes from Excessive Rigidification

| Failure Mode | Mechanistic Basis | Key Quantitative Signatures |

|---|---|---|

| Catalytic Impairment | Loss of coordinated motions (e.g., hinge-bending, loop closure) necessary for substrate binding, transition state stabilization, or product release. | ↓ kcat (10- to 1000-fold); Minimal change in KM; Altered kinetics in stopped-flow assays. |

| Allosteric Inactivation | Restriction of conformational sampling between tense (T) and relaxed (R) states, freezing the protein in an inactive conformation. | Loss of cooperativity (Hill coefficient, nH → 1.0); Increased half-maximal effective concentration (EC50). |

| Aggregation-Prone Folding Intermediates | Stabilization of non-native, partially folded states with exposed hydrophobic patches, diverting the folding pathway. | ↓ Soluble yield in expression; ↑ Aggregates in SEC-MALS; ↑ Signal in Thioflavin T or ANS assays. |

| Slowed Functional Folding | Over-stabilization of the native state (N) relative to the folding transition state (‡), increasing the kinetic barrier to folding. | ↓ Folding rate (kfold) measured by phi-value analysis or relaxation kinetics; ↑ Chevron plot rollover. |

| Loss of Induced Fit | Rigidification of binding interfaces prevents necessary conformational adjustments upon ligand binding. | ↓ Binding affinity (↑ Kd) for native partners; Altered chemical shift perturbations in NMR. |

Experimental Protocols for Detection and Analysis

Protocol 3.1: Characterizing Catalytic and Allosteric Impairment

Objective: Quantify changes in enzyme kinetics and allosteric regulation upon rigidifying mutations. Methodology:

- Enzyme Assay: Perform Michaelis-Menten kinetics using a spectrophotometric or fluorometric assay. Purify wild-type (WT) and mutant proteins via affinity chromatography.

- Data Acquisition: Measure initial velocity (v0) across a range of substrate concentrations [S].

- Analysis: Fit data to the Michaelis-Menten equation (v0 = (Vmax[S])/(KM+[S])) or the Hill equation (v0 = (Vmax[S]nH)/(K0.5nH+[S]nH)) for allosteric enzymes.

- Key Outputs: kcat (Vmax/[E]), KM, nH, K0.5.

Protocol 3.2: Assessing Aggregation and Folding Kinetics

Objective: Monitor aggregation propensity and folding/unfolding rates. Methodology:

- Equilibrium Unfolding: Use differential scanning fluorimetry (DSF) or circular dichroism (CD) with a chemical denaturant (e.g., guanidine HCl). Monitor fluorescence or ellipticity at 222 nm.

- Kinetic Folding/Unfolding: Employ a stopped-flow device coupled to fluorescence. Rapidly mix denatured protein (in high denaturant) with refolding buffer (low denaturant), and vice versa.

- Aggregation Assay: Perform size-exclusion chromatography with multi-angle light scattering (SEC-MALS) post-purification. In parallel, incubate purified protein at stress conditions (e.g., 37°C) and measure turbidity at 340 nm or use ANS/ThioT fluorescence.

- Key Outputs: ΔGunfolding, Cm, kfold, kunfold, aggregation half-time, oligomeric state distribution.

Visualization of Concepts and Workflows

Diagram 1: Decision Pathway for Rigidification Designs

Diagram 2: Loss of Induced Fit via Conformational Restriction

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Analyzing Rigidification Failures

| Reagent / Material | Function in Analysis | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (e.g., Q5) | Introduces specific rigidifying mutations (Pro, disulfide-prone Cys, bulky Trp/Phe) for controlled study. | Creating a library of mutants targeting high B-factor loops. |

| Differential Scanning Fluorimetry (DSF) Dye (e.g., SYPRO Orange) | Binds hydrophobic patches exposed upon unfolding; reports thermal stability (Tm). | High-throughput screening of mutant stability. |

| Chaotropic Denaturants (Guanidine HCl, Urea) | Perturb protein folding equilibrium; used in unfolding assays to determine ΔG and kinetic rates. | Chevron plot analysis to extract kfold and kunfold. |

| ANS (8-Anilino-1-naphthalenesulfonate) | Fluorescent probe for exposed hydrophobic clusters in molten globule or aggregation-prone states. | Detecting misfolded intermediates in rigidified mutants. |

| Stopped-Flow Spectrophotometer/Fluorimeter | Enables measurement of very rapid (ms) kinetic events like protein folding or ligand binding. | Determining the impact of rigidification on folding rate (kfold). |

| SEC-MALS Column (e.g., Superdex 200 Increase) | Separates species by size coupled with absolute molecular weight determination via light scattering. | Quantifying soluble aggregates in purified mutant samples. |

| Nucleotide/Substrate Analogues (Fluorescent/Chromogenic) | Enable real-time monitoring of enzymatic turnover for kinetic parameter extraction (kcat, KM). | Assessing catalytic impairment post-rigidification. |

This whitepaper provides a technical guide for selecting protein mutants with enhanced stability, framed within a broader thesis on utilizing B-factors (Debye-Waller factors) in protein engineering. B-factors, derived from X-ray crystallography data, quantify the mean square displacement of atoms, serving as a direct proxy for local atomic flexibility. The central thesis posits that systematic analysis and manipulation of regions with high B-factors, informed by complementary metrics of conformational entropy and electrostatic potential, enable rational design of stabilized variants. This guide details the integration of these three pillars—Flexibility (B-factors), Entropy, and Electrostatics—into a unified mutant selection pipeline.

Core Principles and Quantitative Metrics

Flexibility Analysis via B-factors

B-factors are normalized and averaged per residue to identify flexible regions. High B-factor regions (e.g., loops, termini) are often targets for stabilization but require nuanced interpretation.

Table 1: B-factor Interpretation and Target Identification

| B-factor Range (Ų) | Interpretation | Typical Structural Element | Design Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| < 20 | Very Rigid | Core β-sheets, buried residues | Avoid mutation; critical for packing. |

| 20 - 40 | Moderately Rigid | Secondary structure elements | Potential for consensus or entropy-reducing mutations. |

| 40 - 60 | Flexible | Surface loops, linker regions | Primary target for rigidity-enhancing mutations (e.g., Pro, disulfide). |

| > 60 | Highly Flexible/Disordered | N/C termini, active site loops | Consider truncation or cyclization; assess functional impact. |

Conformational Entropy Estimation

Entropy penalties upon folding are major determinants of stability. Computational tools estimate changes in backbone (ΔSbb) and side-chain (ΔSsc) entropy.

Table 2: Entropy-Related Parameters for Common Mutations

| Mutation Type | ΔΔS_bb (cal/mol·K) | ΔΔS_sc (cal/mol·K) | Net Entropy Effect |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gly → Any | Unfavorable (+) | Variable | Decreases stability (increases backbone flexibility). |