Geometric Deep Learning for Protein Structures: A New Paradigm in Drug Discovery and Protein Design

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of geometric deep learning (GDL) and its transformative impact on computational biology, specifically for analyzing and designing protein structures.

Geometric Deep Learning for Protein Structures: A New Paradigm in Drug Discovery and Protein Design

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of geometric deep learning (GDL) and its transformative impact on computational biology, specifically for analyzing and designing protein structures. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it covers the foundational principles of GDL, including key symmetry groups and 3D protein representations. It delves into state-of-the-art methodologies and their applications in critical tasks like drug docking, binding affinity prediction, and de novo protein design. The article further addresses persistent challenges such as model generalization and data scarcity, alongside rigorous validation and benchmarking efforts. Finally, it synthesizes key takeaways and outlines future directions, positioning GDL as a cornerstone technology for the next generation of biomedical breakthroughs.

The Geometric Revolution: Core Principles and Data Representations for Protein Structures

Geometric Deep Learning (GDL) represents a transformative paradigm in machine learning that extends neural network capabilities to non-Euclidean domains including graphs, manifolds, and complex geometric structures. Unlike traditional deep learning approaches designed for regularly structured data like images (grids) or text (sequences), GDL provides a principled framework for learning from data with complex relational structures and underlying symmetries. This approach has proven particularly valuable in structural biology and drug discovery, where molecules and proteins inherently possess complex geometric properties that cannot be adequately captured by Euclidean representations alone [1] [2].

The fundamental motivation for GDL stems from the limitations of conventional deep learning architectures when confronted with data that lacks a natural grid structure. Proteins, molecular graphs, and social networks all exhibit relational inductive biases that traditional convolutional neural networks cannot efficiently process. GDL addresses this limitation by explicitly incorporating geometric priors into model architectures, enabling more efficient learning and better generalization on structured data [1]. This capability is particularly crucial for protein structure research, where the spatial arrangement of atoms and residues determines biological function and therapeutic potential.

Theoretical Foundations: Core Principles of GDL

Geometric Deep Learning is built upon several foundational principles that distinguish it from traditional deep learning approaches. These principles enable GDL models to effectively handle the complex structures encountered in protein research and drug discovery.

Geometric Priors

GDL incorporates three fundamental geometric priors that guide model architecture design [1]:

Symmetry and Invariance: Models are designed to be equivariant or invariant to specific transformations such as rotations, translations, and reflections. For protein structures, this means predictions should not change when the entire structure is rotated or translated in space, as these transformations do not alter biological function [3].

Stability: GDL models preserve similarity measures between data instances, ensuring that small distortions in input space correspond to small changes in the representation space. This property is crucial for analyzing protein dynamics and conformational changes.

Multiscale Representations: GDL architectures capture hierarchical patterns at different scales, from local atomic interactions to global protein topology, enabling comprehensive analysis of complex biological systems.

Categories of Geometric Deep Learning

GDL approaches can be categorized into several domains based on their underlying geometric structure [1]:

Table: Categories of Geometric Deep Learning

| Category | Data Type | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Grids | Regularly sampled data (images) | Basic CNN applications |

| Groups | Homogeneous spaces with global symmetries (spheres) | Molecular chemistry, panoramic imaging |

| Graphs | Nodes and edges connecting entities | Social networks, molecular structures |

| Geodesics & Gauges | Manifolds and 3D meshes | Protein structures, computer vision |

For protein structure research, the graph and geodesic categories are particularly relevant, as proteins can be naturally represented as graphs (with residues as nodes and interactions as edges) or as 3D manifolds capturing their complex spatial structure.

GDL Architectures and Implementation

Architectural Building Blocks

Geometric Deep Learning models are constructed from specialized layers that preserve geometric properties [1]:

Linear Equivariant Layers: Core components like convolutions that are equivariant to symmetry transformations. These must be specifically designed for each geometric category.

Non-linear Equivariant Layers: Pointwise activation functions (e.g., ReLUs) that introduce non-linearity while preserving equivariance.

Local and Global Averaging: Pooling operations that impose invariances at different scales, enabling hierarchical feature learning.

These building blocks are combined to create architectures that respect the geometric structure of proteins while maintaining the expressive power needed for complex prediction tasks.

Protein-Specific GDL Implementations

In protein research, GDL models typically follow a structured pipeline that transforms protein data into predictive insights [3]:

Structure Acquisition: Obtaining 3D protein structures through experimental methods (X-ray crystallography, cryo-EM) or computational prediction tools like AlphaFold [4].

Graph Construction: Representing proteins as graphs where nodes correspond to residues or atoms, and edges capture spatial relationships or chemical bonds.

Geometric Feature Encoding: Incorporating spatial, topological, and physicochemical features into node and edge attributes.

Message Passing: Using graph neural networks to propagate information across the structure, capturing both local and global dependencies.

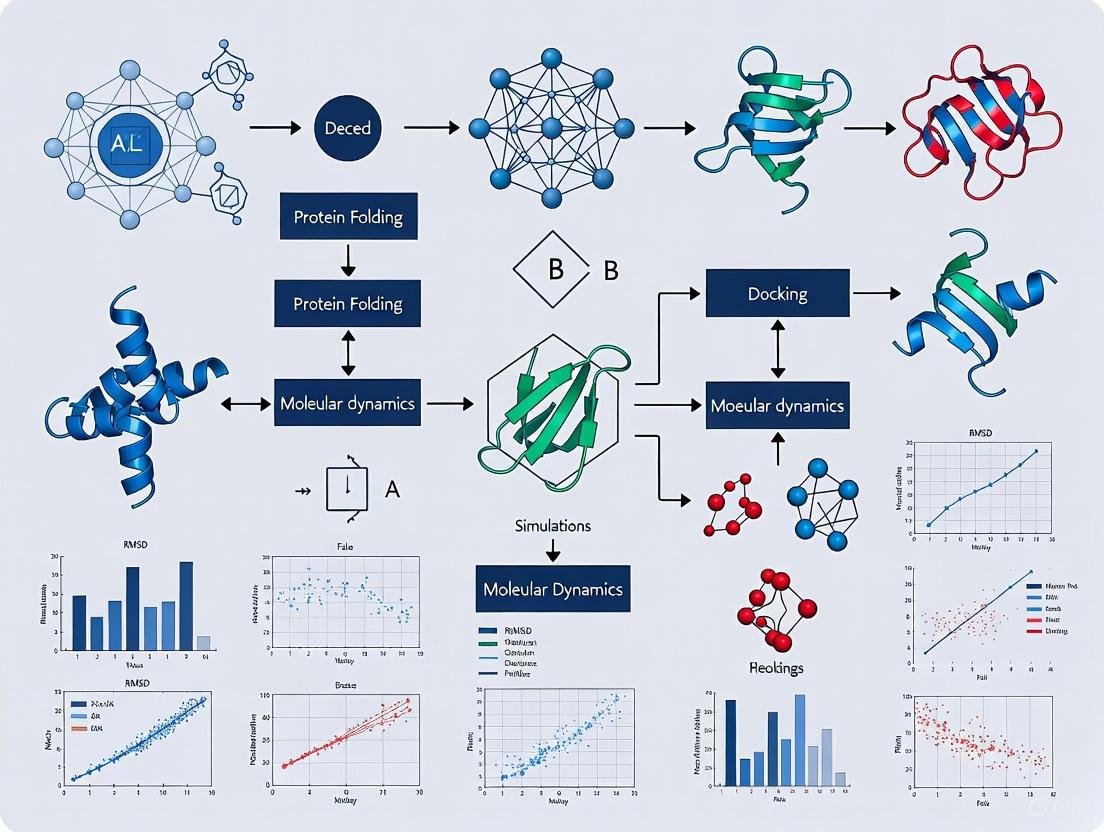

The following diagram illustrates a typical GDL workflow for protein structure analysis:

GDL for Protein Structure Research: Methods and Applications

Key Research Applications

Geometric Deep Learning has enabled significant advances across multiple domains of protein science:

Protein-Protein Interaction Prediction

SpatPPI represents a specialized GDL framework designed to predict protein-protein interactions involving intrinsically disordered regions (IDRs) [5]. This model addresses the critical challenge of capturing interactions with flexible protein regions that lack stable 3D structures. SpatPPI leverages structural cues from folded domains to guide dynamic adjustment of IDRs through geometric modeling and adaptive conformation refinement, achieving state-of-the-art performance on benchmark datasets.

Protein Structure Prediction

GDL has revolutionized protein structure prediction through models like AlphaFold, which employ geometric constraints and equivariant architectures to generate accurate 3D structures from amino acid sequences [4]. These approaches have largely replaced traditional methods such as template-based modeling and ab initio prediction for many applications.

Functional Property Prediction

GDL models can predict various protein properties including stability, binding affinities, and catalytic properties by analyzing 3D structural features [3]. These models capture spatial, topological, and physicochemical features essential to protein function, enabling accurate prediction without costly experimental measurements.

Experimental Framework and Evaluation

To illustrate a complete GDL application, we examine the experimental framework for protein-protein interaction prediction as implemented in SpatPPI [5]:

Table: SpatPPI Experimental Protocol for IDPPI Prediction

| Stage | Method | Key Parameters | Output |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data Preparation | HuRI-IDP dataset construction | 15,000 proteins, 36,300 PPIs, 50% IDPPIs | Training/validation/test splits |

| Graph Representation | Protein structure to directed graph conversion | Nodes: residues, Edges: spatial relationships | Geometric graphs with 7D edge attributes |

| Model Architecture | Edge-enhanced Graph Attention Network (E-GAT) | Dynamic edge updates, two-stage decoding | Residue-level representations |

| Training Protocol | Siamese network with bidirectional computation | Order-invariant aggregation, bilinear function | Interaction probability scores |

| Evaluation | Temporal split with class imbalance adjustment | Metrics: MCC, AUPR (focused on positive class) | Performance comparison against baselines |

The following diagram illustrates the specialized architecture of SpatPPI for handling intrinsically disordered regions:

Performance Benchmarks

GDL models have demonstrated remarkable performance across diverse protein research tasks:

Table: Performance Comparison of GDL Models on Protein Tasks

| Task | Dataset | Baseline Performance | GDL Performance | Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model Quality Assessment | CASP structures | Varies by method | GVP-GNN + PLM: 84.92% RS | +32.63% global RS [6] |

| Protein-Protein Docking | DB5.5 (253 structures) | EquiDock baseline | EquiDock + PLM | 31.01% interface RMSD improvement [6] |

| IDPPI Prediction | HuRI-IDP (15K proteins) | SGPPI, D-SCRIPT | SpatPPI | State-of-the-art MCC/AUPR [5] |

| Binding Affinity Prediction | PDBBind database | Traditional ML | GDL + PLM integration | Significant improvement [6] |

Implementing Geometric Deep Learning for protein research requires specialized tools and resources. The following table catalogs essential components of the GDL research pipeline:

Table: Research Reagent Solutions for GDL Protein Studies

| Resource Category | Specific Tools | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Structure Prediction | AlphaFold, RoseTTAFold, ESMFold | Generate 3D structures from sequences | Foundation for graph construction [3] [4] |

| Geometric Learning Frameworks | PyTorch Geometric, TensorFlow GNN | Specialized GDL implementation | Graph neural network development [6] |

| Protein Language Models | ESM, ProtTrans | Evolutionary sequence representations | Enhancing GDL with evolutionary information [6] |

| Molecular Dynamics | GROMACS, AMBER | Conformational sampling | Data augmentation for dynamic processes [3] |

| Specialized Architectures | GVP-GNN, EGNN, EquiDock | Task-specific geometric models | PPIs, docking, quality assessment [6] |

| Evaluation Metrics | TRA, RMSD, MCC, AUPR | Performance quantification | Benchmarking against experimental data [7] [5] |

Future Directions and Challenges

Despite significant progress, Geometric Deep Learning for protein research faces several important challenges that represent opportunities for future advancement.

Current Limitations

Data Scarcity: High-quality annotated structural datasets remain limited compared to sequence databases, potentially restricting model generalization [3] [6].

Dynamic Representations: Most current GDL frameworks operate on static structures, limiting their ability to capture functionally relevant conformational dynamics and allosteric transitions [3].

Interpretability: Many GDL models function as "black boxes," impeding mechanistic insights that are crucial for guiding experimental design [3].

Generalization: Transferability across protein families, functional contexts, and evolutionary clades remains challenging, particularly for proteins with limited homology to training examples [3].

Emerging Solutions

Future research directions aim to address these limitations through several promising approaches:

Integration with Protein Language Models: Combining GDL with pre-trained protein language models has demonstrated impressive performance gains, with some studies reporting approximately 20% overall improvement across multiple benchmarks [6]. This integration helps overcome data scarcity by leveraging evolutionary information from massive sequence databases.

Dynamic Geometric Learning: Emerging approaches incorporate molecular dynamics simulations and flexibility-aware priors to capture protein dynamics, including cryptic binding pockets and transient interactions [3].

Explainable AI (XAI): Integration of interpretability methods within GDL frameworks is increasing model transparency and providing biological insights [3].

Generative GDL Models: Combining GDL with generative approaches like diffusion models enables de novo protein design, opening new possibilities for therapeutic development [3].

As GDL continues to converge with high-throughput experimentation and generative modeling, it is positioned to become a central technology in next-generation protein engineering and synthetic biology, ultimately accelerating drug discovery and our fundamental understanding of biological systems.

In structural biology, the E(3) and SE(3) symmetry groups provide the fundamental mathematical framework for describing transformations in three-dimensional space. These groups formally characterize the geometric symmetries inherent to all biomolecules, where properties and interactions must remain consistent regardless of molecular orientation or position. The E(3) group (Euclidean group in 3D) encompasses all possible rotations, reflections, and translations in 3D space. The SE(3) group (Special Euclidean group in 3D) includes rotations and translations but excludes reflections, preserving handedness or chirality [8] [9].

Understanding these groups is essential for developing geometric deep learning (GDL) models that process 3D molecular structures. By building equivariance to these symmetries directly into neural network architectures, researchers create models that inherently understand the geometric principles governing biomolecular interactions, leading to remarkable improvements in data efficiency, predictive accuracy, and generalization capability across computational biology tasks [3] [10] [9].

Mathematical Foundations of E(3) and SE(3) Equivariance

Formal Definitions and Transformation Properties

Formally, the E(3) group consists of all distance-preserving transformations of 3D Euclidean space, including translations, rotations, and reflections. The SE(3) group contains all rotations and translations but excludes reflections. A function ( f: X \rightarrow Y ) is equivariant with respect to a group ( G ) that acts on ( X ) and ( Y ) if:

[ {D}{Y}[g]f(x) = f({D}{X}[g]x) \quad \forall g \in G, \forall x \in X ]

where ( DX[g] ) and ( DY[g] ) are the representations of the group element ( g ) in the vector spaces ( X ) and ( Y ), respectively [10] [9]. This mathematical property ensures that when the input to an equivariant network is transformed by any group element ( g ) (e.g., rotated or translated), the output transforms in a corresponding, predictable way. For example, if a molecular structure is rotated, the predicted atomic force vectors rotate accordingly, and binding site predictions move consistently with the rotation [10].

Irreducible Representations and Tensor Operations

Practical implementation of E(3)- and SE(3)-equivariant neural networks relies on decomposing features into irreducible representations of the O(3) or SO(3) groups. Network features are structured as geometric tensors that transform predictably under rotation: scalars (type-0 tensors) remain unchanged, vectors (type-1 tensors) rotate according to standard 3×3 rotation matrices, and higher-order tensors transform via more complex Wigner D-matrices [9]. This decomposition enables networks to learn sophisticated interactions between different geometric entities while strictly preserving transformation properties.

Architectural Implementation of Equivariant Networks

Core Components of Equivariant Graph Neural Networks

Equivariant Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) implement symmetry preservation through specialized layers that maintain equivariance in all internal operations. In these architectures, molecular structures are represented as graphs where nodes correspond to atoms or residues, and edges represent spatial relationships or chemical bonds [8] [10]. The key innovation lies in how message passing and feature updating occur while preserving equivariance.

The message-passing kernels in these networks are constructed as linear combinations of products of learnable radial profiles and fixed angular profiles given by spherical harmonics. Formally, the kernels satisfy:

[ W^{\ell k}(Rg^{-1}x) = D\ell(g) W^{\ell k}(x) D_k(g)^{-1} ]

for every group element ( g ), ensuring rotational equivariance of all messages passed between nodes [9]. This mathematical constraint guarantees that regardless of how the input molecular structure is oriented, the internal representations transform consistently, eliminating the need for data augmentation to teach the network rotational invariance.

Self-Attention Mechanisms in Equivariant Transformers

Recent advances incorporate invariant attention mechanisms into equivariant architectures, creating transformers that operate on 3D molecular data. In these architectures, attention weights are computed as scalar invariants:

[ \alpha{ij} = \frac{\exp(qi^\top k{ij})}{\sum{j'}\exp(qi^\top k{ij'})} ]

where both queries ( qi ) and keys ( k{ij} ) are constructed from equivariant maps, ensuring the attention weights themselves are invariant to rotations and translations [9]. This enables data-dependent weighting of neighbor information while maintaining overall equivariance. The SE(3)-Transformer combines this invariant attention with equivariant value updates, allowing the network to focus on the most relevant molecular substructures regardless of orientation.

Experimental Applications in Structural Biology

Performance Comparison of Equivariant Models

Table 1: Performance Metrics of E(3)/SE(3)-Equivariant Models in Structural Biology Applications

| Model | Application | Key Performance Metrics | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| EquiPPIS | Protein-protein interaction site prediction | Substantial improvement over state-of-the-art; better accuracy with AlphaFold2 predictions than existing methods achieve with experimental structures | [8] |

| DiffGui | Target-aware 3D molecular generation | State-of-the-art performance on PDBbind; generates molecules with high binding affinity, rational structure, and desirable drug-like properties | [11] |

| DeepTernary | Ternary complex prediction for targeted protein degradation | DockQ score of 0.65 on PROTAC benchmark; ~7 second inference time; correlation between predicted BSA and experimental degradation potency | [12] |

| SpatPPI | Protein-protein interactions involving disordered regions | State-of-the-art on HuRI-IDP benchmark; robust to conformational changes in intrinsically disordered regions | [5] |

| NequIP | Interatomic potentials for molecular dynamics | State-of-the-art accuracy with up to 1000x less training data; reproduces structural and kinetic properties from ab-initio MD | [10] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protein-Protein Interaction Site Prediction (EquiPPIS Protocol)

The EquiPPIS methodology demonstrates a complete pipeline for E(3)-equivariant prediction of protein-protein interaction sites [8]:

Input Representation: Convert input protein monomer structures into graphs ( G = (V, E) ) where residues represent nodes and edges connect non-sequential residue pairs within 14Å cutoff distance.

Feature Engineering: Extract sequence- and structure-based node features (evolutionary conservation, physicochemical properties) and edge features (distance, orientation).

Model Architecture: Implement deep E(3)-equivariant graph neural network with multiple Equivariant Graph Convolutional Layers (EGCLs), each updating coordinate and node embeddings using edge information.

Training Protocol: Train on combined benchmark datasets (Dset186, Dset72, Dset_164) using standard train-test splits. Optimize using binary cross-entropy loss for residue classification.

Evaluation Metrics: Assess performance using accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score, Matthews correlation coefficient (MCC), ROC-AUC, and PR-AUC.

This protocol demonstrates the remarkable robustness of E(3)-equivariant models, achieving better accuracy with AlphaFold2-predicted structures than traditional methods achieve with experimental structures [8].

Target-aware 3D Molecular Generation (DiffGui Protocol)

DiffGui implements an E(3)-equivariant diffusion model for generating drug-like molecules within protein binding pockets [11]:

Forward Diffusion Process: Gradually inject noise into both atoms and bonds of ligand molecules over diffusion steps ( q(\mathbf{x}^t | \mathbf{x}^{t-1}, \mathbf{p}, \mathbf{c}) ), where ( \mathbf{p} ) represents protein pocket and ( \mathbf{c} ) represents molecular property conditions.

Dual Diffusion Strategy: Implement two-phase diffusion where bond types diffuse toward prior distribution first, followed by atom type and position perturbation.

Reverse Generation Process: Employ property guidance incorporating binding affinity (Vina Score), drug-likeness (QED), synthetic accessibility (SA), and physicochemical properties (LogP, TPSA) to steer molecular generation.

Architecture Modifications: Extend standard E(3)-equivariant GNNs to update representations of both atoms and bonds within the message passing framework.

Evaluation Framework: Assess generated molecules using Jensen-Shannon divergence of structural features (bonds, angles, dihedrals), RMSD to reference geometries, binding affinity estimates, and various chemical validity metrics.

This approach addresses critical limitations in structure-based drug design by explicitly modeling bond-atom interdependencies and incorporating drug-like properties directly into the sampling process [11].

Research Reagent Solutions for Equivariant Modeling

Table 2: Essential Computational Tools for E(3)/SE(3)-Equivariant Research

| Tool/Resource | Type | Function in Research | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| e3nn | Software Library | Provides primitives for building E(3)-equivariant neural networks | Used in NequIP for implementing equivariant convolutions [10] |

| AlphaFold2/3 | Structure Prediction | Generates high-quality protein structures for training and inference | Provides input structures for EquiPPIS and SpatPPI [8] [5] |

| PDBbind | Curated Dataset | Provides protein-ligand complexes for training and evaluation | Benchmark dataset for DiffGui molecular generation [11] |

| TernaryDB | Specialized Dataset | Curated ternary complexes for targeted protein degradation | Training data for DeepTernary model [12] |

| HuRI-IDP | Benchmark Dataset | Protein-protein interactions involving disordered regions | Evaluation benchmark for SpatPPI [5] |

Workflow Visualization of Equivariant Prediction Models

E(3)-Equivariant PPI Site Prediction (EquiPPIS)

SE(3)-Equivariant Ternary Complex Prediction (DeepTernary)

Future Directions and Challenges

While E(3) and SE(3)-equivariant models have demonstrated remarkable success across structural biology applications, several challenges remain. Current architectures primarily operate on static structural representations, limiting their ability to capture the dynamic conformational ensembles essential to biomolecular function [3]. Future developments must incorporate flexibility-aware priors such as B-factors, backbone torsion variability, or molecular dynamics trajectories to model biologically relevant protein dynamics [3].

Another significant challenge lies in generalization across protein families and functional contexts, particularly for proteins with limited evolutionary information or novel folds. Transfer learning strategies that repurpose geometric models pretrained on large-scale structural datasets show promise for addressing this limitation [3]. As geometric deep learning converges with generative modeling and high-throughput experimentation, E(3) and SE(3)-equivariant architectures are positioned to become central technologies in next-generation computational structural biology and drug discovery [3].

The integration of explainable AI (XAI) techniques with equivariant models represents another critical frontier, enabling researchers to extract mechanistic insights from these sophisticated architectures and guiding experimental design through interpretable predictions [3]. As these models become more widely adopted in pharmaceutical research, their ability to capture complex topological and geometrical information while maintaining physical plausibility will accelerate the development of novel therapeutics for previously undruggable targets [11] [12].

The accurate computational representation of three-dimensional protein structures is a foundational challenge in structural biology and computational biophysics. These representations form the essential input for Geometric Deep Learning (GDL) models, which have emerged as powerful tools for predicting protein functions, interactions, and properties by operating directly on non-Euclidean data domains [3]. The choice of representation fundamentally influences a model's capacity to capture biologically relevant spatial relationships, physicochemical properties, and topological features. Within the framework of GDL for protein science, three principal representation paradigms have been established: grid-based (voxel) representations, surface-based depictions, and spatial graph constructions [3] [13]. Each paradigm offers distinct advantages for encoding different aspects of protein geometry and function, with selection criteria dependent on the specific biological question, computational constraints, and required resolution. This technical guide provides an in-depth analysis of these core representation methodologies, their quantitative characteristics, implementation protocols, and their integral role in advancing protein research through geometric deep learning.

Grid-Based Representations

Core Methodology and Applications

Grid-based or voxel-based representations discretize the three-dimensional space surrounding a protein into a regular lattice of volumetric pixels (voxels). Each voxel is assigned values representing local structural or physicochemical properties, such as electron density, atom type occupancy, or electrostatic potential [13]. This Euclidean structuring makes grid data particularly amenable to processing with 3D convolutional neural networks (3D-CNNs), which can learn hierarchical spatial features directly from the voxelized input.

A key application of grid representations is in protein surface comparison. The 3D-SURFER tool, for instance, employs voxelization to convert a protein surface mesh into a cubic grid, which subsequently undergoes a 3D Zernike transformation [13]. This process yields compact 3D Zernike Descriptors (3DZD)—rotation-invariant feature vectors comprising 121 numerical invariants that enable rapid, alignment-free comparison of global surface shapes across the proteome through simple Euclidean distance calculations [13].

Quantitative Characterization of Grid Representations

Table 1: Key Properties and Metrics for Grid-Based Representations

| Property | Typical Value/Range | Biological Interpretation | Computational Consideration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Grid Resolution | 0.5–2.0 Å | Determines atomic-level detail capture | Higher resolution exponentially increases memory requirements |

| Voxel Dimensions | 64³ to 128³ | Balance between coverage and detail | Powers of 2 optimize CNN performance |

| 3DZD Vector Size | 121 invariants | Compact molecular shape signature | Enables rapid similarity search via Euclidean distance |

| Rotational Invariance | Yes (via 3DZD) | Alignment-free comparison | Eliminates costly superposition steps |

| Surface Approximation | MSROLL algorithm [13] | Molecular surface triangulation | Pre-processing step before voxelization |

Experimental Protocol: Implementing Grid-Based Surface Comparison

Objective: Generate a rotation-invariant shape descriptor for protein surface similarity search.

- Input Preparation: Obtain protein structure in PDB format from experimental sources (X-ray crystallography, cryo-EM) or computational prediction tools (AlphaFold2, RoseTTAFold) [4].

- Surface Mesh Generation: Use the MSROLL program from the Molecular Surface Package (v3.9.3) to extract a triangulated mesh representing the protein's molecular surface [13].

- Voxelization: Discretize the surface mesh into a cubic grid with a recommended step size of 1.0 Å. Assign values of 1 to grid points inside the surface and 0 to points outside.

- 3D Zernike Transformation: Apply the 3DZD algorithm to the cubic grid to compute the 3D Zernike Descriptors. This transformation projects the 3D grid onto a series of orthogonal 3D Zernike polynomials.

- Descriptor Calculation: Generate the final 3DZD feature vector containing 121 rotation-invariant numerical invariants representing the protein's surface shape at multiple hierarchical resolutions [13].

- Similarity Assessment: Compare protein surfaces by computing the Euclidean distance between their respective 3DZD vectors. Smaller distances indicate higher surface shape similarity.

Surface-Based Representations

Geometric Property Mapping and Analysis

Surface representations focus on the protein-solvent interface, encoding critical functional information about binding sites, catalytic pockets, and protein interaction motifs. Unlike grid-based approaches that volume-fill the protein, surface representations are inherently more efficient for characterizing interaction interfaces. The VisGrid algorithm exemplifies this approach by classifying local surface regions into cavities, protrusions, and flat areas using a geometric visibility criterion [13].

This visibility metric quantifies the fraction of unobstructed directions from each point on the protein surface. Cavities (potential binding pockets) are identified as clusters of points with low visibility values, while protrusions manifest as pockets in the negative image of the structure [13]. These geometric features can be color-mapped directly onto the 3D structure for visualization, with typical color coding of red (first-ranked), green (second-ranked), and blue (third-ranked) for each feature type based on their geometric significance [13].

Quantitative Characterization of Surface Representations

Table 2: Analytical Metrics for Surface-Based Representations

| Metric | Calculation Method | Biological Significance | Visualization Approach |

|---|---|---|---|

| Visibility Criterion | Fraction of visible directions from surface point | Identifies concave vs. convex regions | Continuous color mapping from red (cavity) to blue (protrusion) |

| Pocket Volume | Convex hull of pocket residues (ų) | Predicts ligand binding capacity | Ranked coloring (Red>Green>Blue) by volume [13] |

| Surface Area | Accessible surface area (Ų) | Measures solvent exposure | Transparent rendering for context surfaces |

| Conservation Score | Sequence entropy of surface residues | Functional importance assessment | Overlay conservation scores on surface geometry |

| LIGSITEcsc Ranking | Combination of geometry and conservation | Binding site prediction confidence | Top 3 clusters retained and re-ranked |

Experimental Protocol: Surface Feature Detection with VisGrid

Objective: Identify and characterize cavities, protrusions, and flat regions on a protein surface.

- Grid Generation: Project the protein structure onto a 3D grid with 1.0 Å spacing, labeling each grid point as protein interior, surface, or solvent [13].

- Visibility Calculation: For each surface grid point, compute the visibility fraction by casting rays in multiple directions and determining the proportion that extends into solvent without intersecting the protein.

- Feature Classification:

- Cavities: Cluster points with visibility values below threshold τ (typically τ < 0.3)

- Protrusions: Identify as regions with high visibility in the negative image

- Flat Regions: Areas with intermediate visibility values

- Cluster Ranking: Group spatially proximal points into clusters using a distance criterion (typically 3.0 Å). Rank clusters by size (number of constituent grid points).

- Conservation Integration (Optional for LIGSITEcsc): Incorporate evolutionary conservation scores from multiple sequence alignments to re-rank pockets by likely functional importance.

- Visualization: Map computed features onto the molecular surface using a color scheme that maintains sufficient contrast between the foreground elements and background for interpretation [14] [15].

Spatial Graph Representations

Graph Construction for Geometric Deep Learning

Spatial graph representations have emerged as the most expressive paradigm for protein structure analysis in geometric deep learning. In this formulation, proteins are represented as graphs where nodes correspond to amino acid residues and edges encode spatial relationships between them [3] [5]. This non-Euclidean representation preserves the intrinsic geometry of protein structures and enables the application of graph neural networks (GNNs) that respect biological constraints.

Advanced implementations like SpatPPI demonstrate sophisticated graph constructions where edge attributes encompass both distance and angular information [5]. Specifically, edges encode 3D coordinates within local residue frames and quaternion representations of rotation matrices to capture orientational differences between residue geometries [5]. This rich geometric encoding allows GDL models to automatically distinguish between folded domains and intrinsically disordered regions (IDRs) based on their distinct structural signatures, enabling accurate prediction of interactions involving dynamically flexible regions [5].

Quantitative Characterization of Spatial Graph Representations

Table 3: Architectural Parameters for Protein Spatial Graphs

| Graph Component | Attribute Dimensions | Geometric Interpretation | GDL Model Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Node Features | 20-50 dimensions | Evolutionary, structural, physicochemical properties | Initial residue embedding quality |

| Edge Connections | k-NN (k=10-30) or radial cutoff (4-10Å) | Local spatial neighborhood definition | Information propagation scope |

| Distance Attributes | 3D coordinates in local frame | Relative positional relationships | Euclidean equivariance preservation |

| Angular Attributes | 4D quaternion rotations | Orientational geometry | Side-chain interaction modeling |

| Dynamic Edge Updates | Iterative refinement during training | Adaptive to IDR flexibility | Captures conformational changes |

Experimental Protocol: Constructing Spatial Graphs for IDR-Inclusive PPI Prediction

Objective: Build a residue-level spatial graph suitable for predicting protein-protein interactions involving intrinsically disordered regions.

- Structure Acquisition: Obtain 3D protein structures from AlphaFold2 predictions or experimental PDB entries. For IDRs, use AlphaFold2-predicted structures despite their static nature, as they preserve functionally relevant distance information [5].

- Graph Initialization:

- Nodes: Represent each amino acid residue. Encode node features with evolutionary information from multiple sequence alignments, secondary structure assignments, and atomic chemical properties.

- Edges: Connect residues using a k-nearest neighbors approach (k=20) or radial cutoff (8.0 Å). For each edge, compute 7-dimensional attributes: 3D coordinates in local residue frame plus 4D quaternion representing orientational differences [5].

- Geometric Feature Enhancement: Construct local coordinate frames for each residue using Cα-Cβ vectors to embed backbone dihedral angles into multidimensional edge attributes, enabling automatic distinction between folded domains and IDRs.

- Dynamic Edge Refinement: Implement iterative edge updates during model training using a customized edge-enhanced graph attention network (E-GAT). Recompute inter-residue distances and angular relationships based on evolving node embeddings to refine AlphaFold2-predicted structures [5].

- Partition-Aware Decoding: Adopt a two-stage decoding strategy that generates residue-level contact probability matrices preserving partition-specific interaction modes (ordered-ordered, ordered-disordered, disordered-disordered) to prevent signal dilution in disordered regions [5].

Table 4: Critical Resources for Protein Structure Representation Research

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Methods | Primary Function | Representation Compatibility |

|---|---|---|---|

| Structure Prediction | AlphaFold2, RoseTTAFold, ESMFold | Generate 3D models from sequence | All representations (provides input) [4] |

| Surface Analysis | 3D-SURFER, MSROLL, VisGrid, LIGSITEcsc | Surface characterization and comparison | Surface-based [13] |

| Geometric Descriptors | 3D Zernike Descriptors (3DZD) | Rotation-invariant shape similarity | Grid-based [13] |

| Graph Neural Networks | SpatPPI, E-GAT, GNN frameworks | Process spatial graph representations | Spatial graphs [5] |

| Structure Alignment | Combinatorial Extension (CE) | Superposition-based comparison | All representations (validation) [13] |

| Molecular Dynamics | GROMACS, AMBER, NAMD | Assess flexibility and conformational changes | Spatial graphs (dynamic edges) [5] |

| Quality Validation | MolProbity, PROCHECK | Structure quality assessment | All representations (input validation) |

Comparative Analysis and Integration of Representation Paradigms

Each representation paradigm offers distinct advantages for specific applications in protein informatics. Grid-based methods excel at global shape comparison and are computationally efficient for large-scale similarity screening, with 3D Zernike Descriptors enabling rapid retrieval of proteins with similar surface topography without requiring structural alignment [13]. Surface-based approaches provide superior characterization of binding sites and functional interfaces, with algorithms like VisGrid and LIGSITEcsc directly identifying potential interaction pockets through geometric and evolutionary analysis [13]. Spatial graphs offer the most expressive representation for GDL applications, capturing both topological connectivity and intricate geometric relationships between residues, making them particularly effective for predicting interactions involving intrinsically disordered regions and allosteric mechanisms [5].

The integration of multiple representation paradigms often yields the most biologically insightful results. For example, a workflow might employ surface-based methods to identify potential binding pockets, followed by spatial graph analysis to model the allosteric consequences of ligand binding. Similarly, grid-based global shape similarity search can efficiently filter large structure databases, while spatial graph representations enable detailed analysis of specific functional interfaces. This multimodal approach leverages the complementary strengths of each representation, providing a comprehensive computational framework for protein structure analysis in the era of geometric deep learning.

The field of structural biology is built upon a foundational understanding of protein three-dimensional structure, which is critical for elucidating biological function and advancing drug discovery. For decades, this understanding has been primarily derived from experimental methods such as X-ray crystallography, NMR spectroscopy, and cryo-electron microscopy. However, the recent emergence of sophisticated deep learning systems, most notably AlphaFold, has fundamentally transformed this data landscape. This paradigm shift enables researchers to access highly accurate structural predictions for nearly the entire known proteome. For researchers working at the intersection of structural biology and machine learning, particularly in geometric deep learning (GDL) for protein structures, understanding the characteristics, limitations, and appropriate applications of these diverse data sources is paramount. This technical guide provides an in-depth analysis of both experimental and computational protein structure data sources, framed within the context of their utility for advancing geometric deep learning research.

Experimental Structure Determination: The Traditional Gold Standard

Experimental methods have long been the cornerstone of structural biology, providing high-resolution models of protein structures through direct physical measurement.

Core Methodologies and Workflows

The primary experimental techniques for structure determination each follow distinct workflows to resolve atomic-level details:

X-ray Crystallography: This method involves purifying the protein and growing it into a highly ordered crystal. When X-rays are directed at the crystal, they diffract, producing a pattern that can be transformed into an electron density map. Researchers then build an atomic model that best fits this experimental density [16] [4]. The final "deposited model" represents the refined atomic coordinates that interpret the crystallographic data.

Cryo-Electron Microscopy (Cryo-EM): In this technique, protein samples are flash-frozen in a thin layer of vitreous ice and then imaged using an electron microscope. Multiple two-dimensional images are collected and computationally combined to reconstruct a three-dimensional density map, from which an atomic model is built [4].

Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) Spectroscopy: NMR analyzes proteins in solution by applying strong magnetic fields to measure interactions between atomic nuclei. The resulting spectra provide information on interatomic distances and torsional angles, which are used to calculate an ensemble of structures that satisfy these spatial restraints [17] [4]. Unlike other methods, NMR typically yields multiple models representing the dynamic behavior of the protein in solution.

Data Representation and Access

The Protein Data Bank (PDB) serves as the central repository for experimentally determined structures. When accessing structures via platforms like the RCSB PDB Mol* viewer, researchers encounter several representations [17]:

- Model/Deposited Coordinates: The exact atomic coordinates as determined by the experimental method and refined by the researchers.

- Biological Assembly: The structurally or functionally significant form of the molecule, which may require applying symmetry operations to the deposited coordinates (particularly for X-ray structures) or selecting specific subsets from an NMR ensemble.

- Symmetry-Related Views: For crystalline structures, options to visualize the unit cell or supercell provide context for the crystal packing environment.

Table 1: Key Experimental Structure Determination Methods

| Method | Principle | Typical Resolution | Sample State | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| X-ray Crystallography | X-ray diffraction from protein crystals | Atomic (1-3 Å) | Crystalline solid | High resolution; Well-established workflow | Requires crystallization; Crystal packing artifacts |

| Cryo-EM | Electron scattering from vitrified samples | Near-atomic to atomic (1.5-4 Å) | Frozen solution | No crystallization needed; Captures large complexes | Expensive equipment; Complex image processing |

| NMR Spectroscopy | Magnetic resonance properties of nuclei | Atomic (ensemble) | Solution | Studies dynamics; Native solution conditions | Limited to smaller proteins; Complex data analysis |

The AlphaFold Revolution: Computational Structure Prediction

The development of AlphaFold by DeepMind represents a watershed moment in computational biology, providing highly accurate protein structure predictions from amino acid sequences alone.

Architectural Foundations and Workflow

AlphaFold's breakthrough performance stems from its novel neural network architecture that integrates evolutionary, physical, and geometric constraints of protein structures [18]. The system operates through two main stages:

Evoformer Processing: The input amino acid sequence and its multiple sequence alignment (MSA) of homologs are processed through Evoformer blocks. This novel architecture treats structure prediction as a graph inference problem where edges represent residues in spatial proximity. It employs attention mechanisms and triangular multiplicative updates to reason about evolutionary relationships and spatial constraints simultaneously [18].

Structure Module: This component introduces an explicit 3D structure through rotations and translations for each residue (global rigid body frames). Initialized trivially, these rapidly develop into a highly accurate protein structure with precise atomic details through iterative refinement, a process known as "recycling" [18].

Table 2: AlphaFold Version Comparison and Key Features

| Feature | AlphaFold2 (2021) | AlphaFold3 (2024) | ESMFold |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Input | Amino acid sequence + MSA | Amino acid sequence + MSA | Amino acid sequence only |

| Output Type | Protein structure (atomic coordinates) | Protein-ligand complexes | Protein structure |

| Key Innovation | Evoformer + iterative refinement | Expanded to biomolecular complexes | Language model-based |

| Training Data | PDB + evolutionary data | PDB + evolutionary data | Evolutionary scale modeling |

| Confidence Metric | pLDDT (per-residue) | pLDDT + PAE (interaction) | pLDDT |

Comparative Analysis: Data Quality and Limitations

A critical understanding of the relative strengths and limitations of both experimental and predicted structures is essential for appropriate application in research.

Accuracy Metrics and Performance Benchmarks

Rigorous validation studies have quantified the accuracy of AlphaFold predictions relative to experimental structures:

Overall Accuracy: The median RMSD between AlphaFold models and experimental structures is approximately 1.0 Å, compared to 0.6 Å between different experimental structures of the same protein [19]. This indicates excellent overall fold prediction, though with slightly higher deviation than between experimental replicates.

Confidence-Stratified Accuracy: In high-confidence regions (pLDDT > 90), the median RMSD improves to 0.6 Å, matching the variability between experimental structures. However, in low-confidence regions, RMSD can exceed 2.0 Å, indicating substantial deviations [19].

Side Chain Placement: Approximately 93% of AlphaFold-predicted side chains are roughly correct, and 80% show a perfect fit with experimental data, compared to 98% and 94% respectively for experimental structures [19]. This marginal difference becomes significant for applications requiring atomic precision, such as drug docking studies.

Error Analysis: Even the highest-confidence AlphaFold predictions contain errors approximately twice as large as those in high-quality experimental structures, with about 10% of these high-confidence predictions containing substantial errors that render them unusable for detailed analyses like drug discovery [16].

Table 3: Data Quality Comparison: Experimental vs. AlphaFold Structures

| Quality Metric | Experimental Structures | AlphaFold Predictions | Implications for Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Global Backbone Accuracy (Median RMSD) | 0.6 Å (between experiments) | 1.0 Å (vs experiment) | AF captures correct fold; suitable for evolutionary studies |

| High-Confidence Region Accuracy | Reference standard | 0.6 Å (vs experiment) | Suitable for most modeling applications |

| Low-Confidence Region Accuracy | Reference standard | >2.0 Å (vs experiment) | Caution required; may need experimental validation |

| Side Chain Accuracy | 94% perfect fit | 80% perfect fit | Experimental superior for catalytic site analysis |

| Dynamic Regions | Captured by NMR ensembles | Poorly modeled | Experimental essential for flexible linkers, IDRs |

| Ligand/Binding Partners | Directly observed | Not modeled (AF2); Limited (AF3) | Experimental crucial for complex studies |

Specific Limitations and Considerations

Both data sources present important limitations that researchers must consider:

AlphaFold's Blind Spots:

- Intrinsically disordered regions (IDRs) and flexible linkers are predicted with low confidence and often deviate from experimental observations [19].

- Domain orientations in multidomain proteins, particularly without well-defined relative positions, are essentially random and reflected in poor PAE scores [19].

- Environmental factors including ligands, ions, covalent modifications, and membrane contexts are not natively accounted for in AlphaFold2 [16].

- Predictions for proteins lacking homologous sequences in training data show reduced accuracy [4].

Experimental Challenges:

- Crystallization may introduce artifacts or miss biologically relevant conformations.

- Solution-state dynamics are lost in crystalline environments.

- Technical limitations include radiation damage in X-ray crystallography and resolution limits in cryo-EM.

- The experimental structure determination process remains time-consuming and resource-intensive [4].

Integration with Geometric Deep Learning

The convergence of protein structure data with geometric deep learning (GDL) represents a powerful synergy for advancing protein engineering and design.

GDL Applications and Data Requirements

Geometric deep learning operates on non-Euclidean domains, capturing spatial, topological, and physicochemical features essential to protein function [3]. This approach addresses key limitations of traditional machine learning models that often reduce proteins to oversimplified representations overlooking allosteric regulation, conformational flexibility, and solvent-mediated interactions [3]. Specific applications include:

- Stability Prediction: GDL models use structural graphs to predict the effects of mutations on protein stability.

- Functional Annotation: Spatial and chemical features extracted from structures enable inference of molecular function.

- Protein-Protein Interactions: Models like SpatPPI leverage geometric learning to predict interactions involving intrinsically disordered regions by representing protein structures as graphs with nodes corresponding to residues and edges encoding spatial relationships [5].

- De Novo Protein Design: Generative GDL models create novel protein structures with desired functions.

Data Preprocessing for GDL Pipelines

Implementing GDL for protein structures requires careful data preprocessing:

Structure Acquisition: Researchers can utilize experimental structures from the PDB or predicted structures from AlphaFold, RoseTTAFold, or ESMFold [3]. The choice depends on availability and the specific research question.

Graph Construction: Protein structures are converted into graphs where nodes represent amino acid residues and edges capture spatial relationships. Critical considerations include:

Handling Structural Uncertainty: GDL models can incorporate confidence metrics from prediction tools (e.g., pLDDT, PAE) or experimental quality indicators (e.g., B-factors) to weight the reliability of different structural regions [3].

Table 4: Key Research Resources for Protein Structure Analysis

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Platforms | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Structure Prediction | AlphaFold, RoseTTAFold, ESMFold | Generate 3D models from sequence | Initial structure acquisition; homology modeling |

| Structure Visualization | Mol*, PyMOL, ChimeraX | 3D visualization and analysis | Structural analysis; figure generation |

| Geometric Deep Learning | SpatPPI, Evoformer-based models | Structure-based prediction | PPI prediction; stability analysis; function annotation |

| Experimental Validation | Phenix suite, Cryo-EM pipelines | Experimental structure determination | Validating predictions; determining novel structures |

| Data Repositories | PDB, Model Archive | Store and access structures | Data sourcing; benchmarking |

| Quality Assessment | pLDDT, PAE, MolProbity | Evaluate model quality | Validating predictions; assessing experimental models |

The contemporary data landscape for protein structures is fundamentally hybrid, integrating both experimental and computationally predicted sources. For researchers in geometric deep learning, this expanded landscape offers unprecedented opportunities while demanding critical awareness of the appropriate application of each data type. Experimental structures remain essential for characterizing atomic-level details, validating predictions, and studying dynamic regions and complexes. Meanwhile, AlphaFold predictions provide broad structural coverage and serve as excellent hypotheses for guiding experimental design. The most powerful research approaches will strategically combine both data types—using predicted structures for initial insights and large-scale analyses, while relying on experimental validation for mechanistic studies and applications requiring high precision. As geometric deep learning continues to evolve, its integration with both experimental and predicted structural data will undoubtedly drive future innovations in protein science, drug discovery, and synthetic biology.

Geometric Deep Learning (GDL) has emerged as a transformative framework for computational biology, enabling researchers to model the intricate three-dimensional structures of proteins with unprecedented fidelity. Unlike traditional neural networks designed for Euclidean data, GDL operates directly on non-Euclidean domains—including graphs, manifolds, and point clouds—making it uniquely suited for representing molecular structures. The fundamental architectures within GDL, particularly Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) and equivariant models, have demonstrated remarkable success in predicting protein functions, interactions, and properties by leveraging their inherent spatial geometries. This technical guide provides an in-depth examination of these core architectures within the context of protein structure research, offering researchers and drug development professionals both theoretical foundations and practical methodologies.

Core Architectural Foundations

Graph Neural Networks for Molecular Representation

Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) form the foundational architecture for most GDL applications in protein science. These networks operate on graph-structured data where nodes represent amino acid residues and edges capture spatial or chemical relationships between them. The core innovation of GNNs lies in their message-passing mechanism, where each node iteratively aggregates information from its neighbors to build increasingly sophisticated representations of its local structural environment [20].

In protein structure applications, GNNs typically employ two primary architectures: Graph Convolutional Networks (GCNs) and Graph Attention Networks (GATs). GCNs apply spectral graph convolutions with layer-wise propagation rules, while GATs introduce attention mechanisms that assign learned importance weights to neighboring nodes during message aggregation [20]. This capability is particularly valuable for proteins, where certain residue interactions (e.g., catalytic triads or binding interfaces) play disproportionately important roles in function. When implementing GNNs for protein graphs, standard practice involves connecting nodes (residues) if they have atom pairs within a threshold distance (typically 4-8 Å), creating what's known as a residue contact network [20].

Table 1: Core GNN Architectures for Protein Applications

| Architecture | Key Mechanism | Protein-Specific Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Graph Convolutional Network (GCN) | Spectral graph convolutions with layer-wise propagation rules | Efficient processing of residue contact maps; captures local chemical environments | Limited expressivity for long-range interactions; isotropic filtering |

| Graph Attention Network (GAT) | Self-attention mechanism weighting neighbor contributions | Adaptively focuses on critical residue interactions (e.g., active sites); handles variable-sized neighborhoods | Higher computational cost; requires more data for stable attention learning |

| KAN-Augmented GNN (KA-GNN) | Fourier-based Kolmogorov-Arnold networks in embedding, message passing, and readout | Enhanced approximation capability; improved parameter efficiency; inherent interpretability | Emerging methodology with less extensive validation [21] |

Equivariant Models for Geometric Structure Processing

Equivariant models represent a significant architectural advancement beyond standard GNNs by explicitly encoding geometric symmetries into their operations. These networks are designed to be equivariant to transformations in 3D space—specifically rotations, translations, and reflections—meaning their outputs transform predictably when their inputs are transformed. This property is crucial for biomolecular modeling, where a protein's function is independent of its global orientation but fundamentally depends on the relative spatial arrangement of its residues [3].

The most common equivariant architectures operate on the principles of E(3) or SE(3) equivariance, respecting the symmetries of 3D Euclidean space. These models typically represent each residue not just as a node in a graph, but as a local coordinate frame comprising a Cα coordinate and N-Cα-C rigid orientation [22]. This representation enables the network to reason about both positional and orientational relationships between residues, capturing geometric features like backbone dihedral angles and side-chain orientations that are critical for understanding protein function [5]. RFdiffusion exemplifies this approach, using an SE(3)-equivariant architecture based on RoseTTAFold to generate novel protein structures through a diffusion process [22].

Table 2: Equivariant Architectures for Protein Structure Modeling

| Model Type | Symmetry Group | Key Protein Applications | Notable Implementations |

|---|---|---|---|

| E(3)-Equivariant GNN | Euclidean group E(3) | Molecular property prediction; binding affinity estimation | Multiple frameworks with invariant/equivariant layers [3] |

| SE(3)-Equivariant Diffusion | Special Euclidean group SE(3) | De novo protein design; protein structure generation | RFdiffusion [22] |

| Frame-Based Equivariant Models | Rotation and translation equivariance | Protein-protein interaction prediction; conformational refinement | SpatPPI [5] |

Advanced Architectural Innovations

Hybrid and Specialized Architectures

Recent architectural innovations have focused on hybrid approaches that combine the strengths of multiple GDL paradigms. The Kolmogorov-Arnold GNN (KA-GNN) framework represents one such advancement, integrating Fourier-based Kolmogorov-Arnold networks into all three fundamental components of GNNs: node embedding, message passing, and graph-level readout [21]. This architecture replaces the conventional multi-layer perceptrons (MLPs) typically used in GNNs with learnable univariate functions based on Fourier series, enabling the model to capture both low-frequency and high-frequency structural patterns in protein graphs [21].

Another significant hybrid approach is exemplified by SpatPPI, which combines equivariant principles with specialized graph attention mechanisms for predicting protein-protein interactions involving intrinsically disordered regions (IDRs) [5]. SpatPPI constructs local coordinate frames for each residue and embeds backbone dihedral angles into multidimensional edge attributes, enabling automatic distinction between folded domains and IDRs. It employs a customized edge-enhanced graph self-attention network (E-GAT) that alternates between updating node and edge attributes, dynamically refining inter-residue distances and angular relationships based on evolving node embeddings [5].

Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

Standard Experimental Pipeline for GDL Protein Modeling

The following Graphviz diagram illustrates the complete workflow for applying GDL architectures to protein structure research:

Implementation Protocol for PPI Prediction with SpatPPI-like Architecture

For researchers implementing protein-protein interaction prediction with a focus on intrinsically disordered regions, the following detailed methodology adapted from SpatPPI provides a robust foundation [5]:

Graph Construction Phase:

- Generate protein structures using AlphaFold2 for all sequences in your dataset.

- Convert each protein structure into a directed graph where nodes represent amino acid residues.

- Construct a local coordinate frame for each residue, capturing both positional (3D coordinates) and orientational (rotation matrix quaternions) information across 7-dimensional edge attributes.

- Encode node attributes with evolutionary information from multiple sequence alignments, secondary structure predictions, and atomic chemical properties.

Network Architecture Configuration:

- Implement a Siamese network framework to process protein pairs.

- Employ an edge-enhanced graph self-attention network (E-GAT) with alternating node and edge attribute updates.

- Configure dynamic edge updates that reconstruct spatially enriched residue embeddings based on learned node representations.

- Apply a two-stage decoding strategy that first generates residue-level contact probability matrices preserving partition-specific interaction modes (ordered-ordered, ordered-disordered, disordered-disordered).

Training Protocol:

- Utilize the HuRI-IDP dataset or comparable PPI data with known disordered region annotations.

- Apply bidirectional computation (forward and reversed protein pair orders) to eliminate input-order biases.

- Use Matthews correlation coefficient (MCC) and area under the precision-recall curve (AUPR) as primary evaluation metrics instead of AUROC, as they better handle class imbalance characteristic of PPI data.

- Train with a positive-to-negative sample ratio of 1:10 to reflect biological network sparsity.

Validation and Interpretation:

- Perform molecular dynamics simulations on a subset of predictions to assess robustness to conformational changes in IDRs.

- Visualize final residue representations to verify clustering patterns between ordered and disordered regions.

- Compare against baseline methods (SGPPI, D-SCRIPT, Topsy-Turvy) using standardized benchmark datasets.

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for GDL Protein Research

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| AlphaFold2/3 | Structure Prediction | Predicts 3D protein structures from sequence | Provides input structures for graph construction [5] [4] |

| RoseTTAFold | Structure Prediction | Alternative structure prediction engine | Basis for RFdiffusion and other generative models [22] |

| RFdiffusion | Generative Model | De novo protein design via diffusion | Creates novel protein structures conditional on specifications [22] |

| ProteinMPNN | Sequence Design | Designs sequences for given protein backbones | Complements structure generation models [22] |

| ESMFold | Structure Prediction | Rapid structure prediction using language model | Alternative to AlphaFold for large-scale applications [3] |

| MD Simulations | Molecular Dynamics | Samples conformational diversity | Validates model robustness to structural fluctuations [5] |

Architectural Comparison and Performance Benchmarks

Quantitative Performance Analysis

Table 4: Performance Comparison of GDL Architectures on Protein Tasks

| Architecture | Task | Performance Metrics | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| SpatPPI | IDPPI Prediction | State-of-the-art on HuRI-IDP benchmark; stable under MD simulations [5] | Dynamic adjustment for IDRs; geometric awareness |

| KA-GNN | Molecular Property Prediction | Outperforms conventional GNNs on 7 benchmarks; superior computational efficiency [21] | Fourier-based representations; enhanced interpretability |

| RFdiffusion | De Novo Protein Design | Experimental validation of diverse structures; high AF2 confidence (pAE < 5) [22] | Conditional generation; SE(3) equivariance |

| GCN/GAT Baseline | PPI Prediction | Strong performance on Human and S. cerevisiae datasets [20] | Established methodology; extensive benchmarking |

Future Directions and Challenges

The architectural evolution of GDL for protein science continues to advance rapidly. Key challenges include improving model interpretability, capturing conformational dynamics more effectively, and generalizing to unseen protein families [3]. Emerging approaches are addressing these limitations through several promising directions:

Integration of Dynamic Information: Future architectures will increasingly incorporate molecular dynamics simulations directly into geometric learning pipelines, either through ensemble-based graphs or flexibility-aware priors integrated into node and edge embeddings [3].

Explainable AI Integration: Models like GDLNN and KA-GNN are pioneering the integration of interpretability directly into architecture design, enabling researchers to identify chemically meaningful substructures that drive predictions [23] [21].

Generative Capabilities Expansion: Equivariant diffusion models represent just the beginning of generative protein design. Future architectures will likely combine the conditional generation capabilities of RFdiffusion with the geometric awareness of SpatPPI to enable precise functional protein design [22].

As these architectures mature, they will increasingly serve as the computational foundation for transformative advances in drug discovery, synthetic biology, and fundamental molecular science.

From Theory to Therapy: GDL Methods for Drug Discovery and Protein Engineering

The accurate prediction of protein-ligand interactions through molecular docking and binding affinity estimation represents a cornerstone of modern computational biology and structure-based drug design. Traditional docking methods, which rely on search-and-score algorithms and often treat proteins as rigid bodies, have long faced limitations in capturing the dynamic nature of biomolecular recognition [24]. The integration of geometric deep learning (GDL) has catalyzed a paradigm shift, enabling models to operate directly on the non-Euclidean domains of molecular structures and capture essential spatial, topological, and physicochemical features [3]. This technical guide examines current GDL methodologies, benchmarks their performance, and provides detailed protocols for their application, framing these advances within the broader context of geometric deep learning for protein structure research.

Geometric Deep Learning Foundations for Molecular Interactions

Geometric deep learning (GDL) provides a principled framework for developing models that respect the fundamental symmetries and geometric priors inherent to biomolecular structures. GDL architectures are designed to be equivariant to rotations, translations, and reflections—transformations under which the physical laws governing molecular interactions remain invariant [3]. This equivariance ensures that a model's predictions are consistent regardless of the global orientation of a protein-ligand complex in 3D space, a property critical for robust generalization.

For protein-ligand interaction prediction, GDL typically represents molecular structures as graphs. In this representation, nodes correspond to atoms or residues, encoding features such as element type, charge, and evolutionary profile. Edges represent spatial or chemical relationships, capturing interactions such as covalent bonds, ionic interactions, and hydrogen bonding networks [5] [3]. Equivariant Graph Neural Networks (EGNNs) and other geometric architectures then perform message passing over these graphs, iteratively updating node and edge features to integrate information from local molecular neighborhoods and capture long-range interactions critical for allostery and conformational change [24] [3].

A significant challenge in the field is moving beyond static structural representations. Proteins and ligands are dynamic entities that undergo conformational changes upon binding. Next-generation GDL models are beginning to address this limitation by incorporating dynamic information from molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, multi-conformational ensembles, and flexibility-aware priors such as B-factors and disorder scores directly into their geometric learning pipelines [3].

Deep Learning Approaches for Docking and Affinity Prediction

A Taxonomy of Computational Docking Methods

Table 1: Classification of Molecular Docking Methods Based on Flexibility and Approach

| Method Category | Description | Key Features | Example Methods |

|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Rigid Docking | Treats both protein and ligand as rigid bodies. | Fast but inaccurate; oversimplifies binding process. | Early AutoDock versions [24] |

| Semi-Flexible Docking | Allows ligand flexibility while keeping the protein rigid. | Balanced efficiency and accuracy; limited for flexible proteins. | AutoDock Vina, GOLD [24] |

| Flexible Docking | Models flexibility for both ligand and protein. | High computational cost; challenging search space. | FlexPose, DynamicBind [24] |

| Deep Learning Docking | Uses GDL to predict binding structures and affinities. | Rapid, can handle flexibility; generalizability challenges. | EquiBind, DiffDock, TankBind [24] |

| Co-folding Methods | Predicts protein-ligand complexes directly from sequence. | End-to-end prediction; training biases toward common sites. | NeuralPLexer, RoseTTAFold All-Atom, Boltz-1/Boltz-1x [25] |

Key Methodological Approaches

Geometric Deep Learning for Docking

Recent GDL approaches have demonstrated remarkable success in predicting the 3D structure of protein-ligand complexes. EquiBind, an Equivariant Graph Neural Network (EGNN), identifies key interaction points on both the ligand and protein, then uses the Kabsch algorithm to find the optimal rotation matrix that aligns these points [24]. TankBind employs a trigonometry-aware GNN to predict a distance matrix between protein residues and ligand atoms, subsequently reconstructing the 3D complex structure through multi-dimensional scaling [24].

A particularly impactful innovation has been the introduction of diffusion models to molecular docking. DiffDock employs a diffusion process that progressively adds noise to the ligand's degrees of freedom (translation, rotation, and torsion angles), training an SE(3)-equivariant network to learn a denoising score function that iteratively refines the ligand's pose toward a plausible binding configuration [24]. This approach achieves state-of-the-art accuracy while operating at a fraction of the computational cost of traditional methods.

Incorporating Protein Flexibility

A major limitation of many early DL docking methods was the treatment of proteins as rigid structures. Flexible docking approaches aim to overcome this by modeling protein conformational changes. FlexPose enables end-to-end flexible modeling of protein-ligand complexes regardless of input conformation (apo or holo) [24]. DynamicBind uses equivariant geometric diffusion networks to model backbone and sidechain flexibility, enabling the identification of cryptic pockets—transient binding sites not visible in static structures [24].

Co-folding for Complex Prediction

Co-folding methods represent a revolutionary advance by predicting protein-ligand interactions directly from amino acid and ligand sequences, effectively extending the principles of AlphaFold2 to molecular complexes. These include NeuralPLexer, RoseTTAFold All-Atom, and the Boltz series [25]. However, these models face challenges, particularly in predicting allosteric binding sites, as their training data is heavily biased toward orthosteric sites [25]. A benchmark study involving 17 orthosteric/allosteric ligand sets found that while Boltz-1x produced high-quality predictions (>90% passing PoseBusters quality checks), these methods generally favored placing ligands in orthosteric sites even when allosteric binding was expected [25].

Diagram 1: Co-folding workflow for predicting protein-ligand complexes from sequence, highlighting the challenge of allosteric site prediction.

Binding Affinity Prediction

Accurate prediction of binding affinities remains a formidable challenge. While classical scoring functions struggle with generalization, GDL-based approaches have shown promise. However, a critical issue identified in recent literature is the data leakage between popular training sets (e.g., PDBbind) and benchmark datasets (e.g., CASF), which has led to inflated performance metrics and overestimation of model capabilities [26].

The PDBbind CleanSplit dataset was developed to address this problem by applying a structure-based filtering algorithm that eliminates train-test data leakage and reduces redundancies within the training set [26]. When state-of-the-art models like GenScore and Pafnucy were retrained on CleanSplit, their performance dropped markedly, indicating their previously reported high performance was largely driven by data leakage rather than genuine generalization [26].

The recently introduced GEMS (Graph neural network for Efficient Molecular Scoring) model maintains strong benchmark performance when trained on CleanSplit, suggesting more robust generalization capabilities [26]. GEMS leverages a sparse graph modeling of protein-ligand interactions and transfer learning from language models to achieve accurate affinity predictions on strictly independent test datasets [26].

Experimental Protocols and Benchmarking

Quantitative Performance Comparison

Table 2: Performance Benchmarks for Deep Learning-Based Docking and Affinity Prediction

| Method | Category | Key Metric | Performance | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DiffDock [24] | DL Docking | Top-1 RMSD < 2.0Å (on PDBBind) | State-of-the-art pose prediction | Limited explicit protein flexibility |

| Boltz-1x [25] | Co-folding | >90% PoseBusters pass rate | High quality ligand poses | Bias toward orthosteric sites |

| GEMS [26] | Affinity Prediction | RMSE on CASF benchmark | Robust performance on CleanSplit | - |

| FlexPose [24] | Flexible Docking | Cross-docking accuracy | Improved apo-structure docking | Computational complexity |

| Retrained Models on CleanSplit [26] | Affinity Prediction | Performance drop vs. original | Highlight data leakage issues | Overestimated generalization |

Benchmarking Strategies and Protocols

Docking Task Definitions

Rigorous evaluation requires testing models on distinct docking tasks of varying difficulty:

- Re-docking: Docking a ligand back into its bound (holo) receptor conformation. Evaluates pose prediction accuracy in an idealized setting [24].

- Cross-docking: Docking ligands to alternative receptor conformations from different ligand complexes. Simulates real-world scenarios where the protein conformation is not perfectly optimized for the specific ligand [24].

- Apo-docking: Using unbound (apo) receptor structures. A highly realistic setting requiring models to infer induced fit effects [24].

- Blind docking: Predicting both ligand pose and binding site location without prior knowledge of the binding site [24].

Diagram 2: Workflow for rigorous benchmarking of protein-ligand interaction prediction methods.

Addressing Data Leakage in Affinity Prediction

The protocol for creating a non-leaky benchmark, as exemplified by PDBbind CleanSplit, involves:

- Structure-based clustering using a combined assessment of protein similarity (TM-scores), ligand similarity (Tanimoto scores), and binding conformation similarity (pocket-aligned ligand RMSD) [26].

- Identifying and removing training complexes that closely resemble any test complex according to defined similarity thresholds.

- Eliminating training complexes with ligands identical to those in the test set (Tanimoto > 0.9) to prevent ligand-based memorization [26].

- Reducing redundancy within the training set by iteratively removing complexes from similarity clusters to discourage memorization and encourage genuine learning [26].

Target Identification Benchmark

A demanding new benchmark evaluates a model's ability to identify the correct protein target for a given active molecule—a task known as the inter-protein scoring noise problem. Classical scoring functions typically fail at this task due to scoring variations between different binding pockets [27]. A model with truly generalizable affinity prediction capability should successfully identify the correct target by predicting higher binding affinity for it compared to decoy targets. Recent evaluations indicate that even advanced models like Boltz-2 struggle with this challenge, suggesting that generalizable understanding of protein-ligand interactions remains elusive [27].