From Sequence to Therapy: The Central Dogma of Protein Engineering in Drug Development

This article explores the modern interpretation of the central dogma in protein engineering, framing it as the guided flow of information from sequence to structure to function for designing novel...

From Sequence to Therapy: The Central Dogma of Protein Engineering in Drug Development

Abstract

This article explores the modern interpretation of the central dogma in protein engineering, framing it as the guided flow of information from sequence to structure to function for designing novel therapeutics. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, it details foundational concepts, state-of-the-art computational and experimental methodologies, strategies for overcoming key optimization challenges, and frameworks for validating engineered proteins. By integrating insights from deep learning, directed evolution, and rational design, this review provides a comprehensive guide for developing high-performance proteins with enhanced efficacy, stability, and specificity for clinical applications, from targeted drug delivery to enzyme engineering.

The Protein Engineering Central Dogma: From Genetic Code to Functional Molecules

The classical Central Dogma of molecular biology, as articulated by Francis Crick, posited a unidirectional flow of genetic information: DNA → RNA → protein [1]. While this framework correctly established the fundamental relationships between these core biological molecules, contemporary research has revealed a far more complex and dynamic reality. The modern understanding extends this paradigm beyond simple information transfer to encompass the functional realization of genetic potential, crystallized as Sequence → Structure → Function.

This expanded framework acknowledges that biological information does not merely flow linearly but is regulated, interpreted, and expressed through multi-layered systems. The sequence of nucleotides in DNA dictates the sequence of amino acids in a protein, which in turn determines the protein's three-dimensional structure. This structure is the primary determinant of the protein's specific biological function [2]. This conceptual advancement is driven by insights from systems biology, which demonstrates that information flows multi-directionally between different tiers of biological data (genes, transcripts, proteins, metabolites), giving rise to the emergent properties of cellular function [3]. The following sections will delineate the quantitative rules, regulatory mechanisms, and experimental frameworks that define this modern Central Dogma, with a specific focus on its implications for protein engineering and therapeutic development.

Quantitative Foundations of Gene Expression

The expression of a protein at a defined abundance is a fundamental requirement for both natural biological systems and engineered organisms. The modern Central Dogma incorporates a quantitative understanding of the four basic rates governing this process: transcription, translation, mRNA decay, and protein decay [4].

The Crick Space and the Precision-Economy Trade-off

Research has systematically analyzed the combinations of transcription (βm) and translation (βp) rates—conceptualized as "Crick space"—used by thousands of genes across diverse organisms to achieve their steady-state protein levels. A striking finding is that approximately half of the theoretically possible Crick space is depleted; genes strongly avoid combinations of high transcription with low translation [4]. This pattern is observed in organisms ranging from E. coli to H. sapiens and is not due to a mechanistic constraint, as synthetic constructs can access this region.

The depletion is explained by an evolutionary trade-off between precision and economy:

- Precision: High transcription with low translation minimizes stochastic fluctuations (noise) in protein abundance because the relative fluctuations in the number of abundant mRNAs are small [4].

- Economy: High transcription rates incur significant biosynthetic costs for the cell, penalizing growth rates [4].

The boundary of the depleted region is defined by a constant ratio of translation to transcription, βp/βm = k. The value of k varies significantly between organisms, reflecting their distinct biological constraints (Table 1).

Table 1: Boundary Parameters of the Depleted Crick Space Across Model Organisms

| Organism | Boundary Constant (k) | Max Translation Rate (proteins/mRNA/hour) |

|---|---|---|

| S. cerevisiae (Yeast) | 1.1 ± 0.1 | 104 |

| E. coli (All Genes) | 14 ± 3 | 104 |

| E. coli (Non-essential Genes) | 44 ± 9 | 104 |

| M. musculus (Mouse) | 44 ± 3 | 103.6 |

| H. sapiens (Human) | 66 ± 4 | 103.6 |

Experimental Protocol: Genome-Wide Measurement of Central Dogma Rates

The quantitative principles outlined above were established using high-throughput experimental methodologies.

Protocol: Measuring Crick Space Parameters via mRNA-seq and Ribosome Profiling [4]

- Cell Culture and Harvesting: Grow cells of interest (e.g., S. cerevisiae, E. coli, mammalian cell lines) under rapid growth conditions to a mid-log phase. Rapidly harvest cells to snapshot the in vivo state.

- mRNA Sequencing (mRNA-seq): a. RNA Extraction: Isolate total RNA using a commercial kit, followed by poly-A selection for eukaryotes or rRNA depletion for bacteria. b. Library Preparation: Fragment the RNA, reverse-transcribe to cDNA, and attach sequencing adaptors. c. Sequencing & Analysis: Perform high-throughput sequencing. The normalized read count (e.g., Reads Per Kilobase per Million mapped reads, RPKM) for each gene provides a quantitative measure of its mRNA abundance. Transcription rates (βm) can be inferred from these abundances combined with mRNA decay rates.

- Ribosome Profiling (Ribo-seq): a. Cell Lysis and Nuclease Digestion: Lyse cells and treat with a specific nuclease that digests mRNA regions not protected by ribosomes. b. Ribosome Protection Fragment Isolation: Isolate the protected mRNA fragments (ribosome footprints) by size selection. c. Library Preparation and Sequencing: Convert the footprints into a sequencing library. The sequence reads reveal the exact positions of ribosomes on transcripts. d. Quantification: The density of ribosome footprints on a given mRNA, normalized by the mRNA abundance, provides a direct measure of its translation rate (βp).

- Data Integration: Integrate mRNA-seq and Ribo-seq data for the same genes to plot the transcription and translation rates, populating the Crick space and revealing the depleted region.

Orchestration by Non-Coding RNAs and the Environment

The modern Central Dogma accounts for the pervasive role of non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs) and environmental signals that regulate the flow of information from sequence to functional output, challenging the notion of a simple one-way street [1] [5].

Non-Coding RNAs as Master Regulators

Once dismissed as "transcriptional noise," ncRNAs are now recognized as central players that orchestrate the Central Dogma by serving as scaffolds, catalysts, and fine-tuners of gene expression [5]. They operate as components of highly integrated and dynamic regulatory networks, known as RNA interactomes, which are flexible enough to adapt to shifting cellular demands.

Table 2: Key Non-Coding RNA Classes and Their Regulatory Functions

| ncRNA Class | Primary Function | Impact on Central Dogma |

|---|---|---|

| miRNA (microRNA) | Binds to target mRNAs, leading to their degradation or translational repression. | Regulates the "RNA → Protein" step by disposing of messenger RNA [1]. |

| lncRNA (Long Non-coding RNA) | Involved in epigenetic regulation, transcriptional control, and nuclear organization. | Can regulate the "DNA → RNA" step by altering chromatin state, and also regulate protein modifications [1]. |

| piRNA (Piwi-interacting RNA) | Binds to Piwi proteins to silence transposable elements in the germline. | Protects the integrity of the "DNA" sequence from reshuffling by "jumping genes" [1]. |

| Transposable Elements (e.g., LINE-1) | Ancient viral fragments that can "copy-and-paste" themselves to new genomic locations. | Can alter the "DNA" sequence itself, demonstrating that proteins (e.g., ORF2) can reshape the genome [1]. |

Gene-Environment Interaction and Epigenetics

The initiation of the Central Dogma process is not autonomous; DNA does not decide when to transcribe itself. Environmental signals—including nutrition, toxins, stress, and social factors—are the primary triggers that turn gene expression on or off in the correct sequence [1]. This gene-environment interaction is mediated by epigenetic mechanisms, which include:

- DNA methylation: The addition of methyl groups to DNA, which typically tightens chromatin and silences genes.

- Histone modifications: Changes to the proteins around which DNA is wound, altering chromatin accessibility.

- These mechanisms respond to environmental cues and create a dynamic layer of regulation that controls the accessibility of DNA sequences for transcription, thereby directly influencing the "Sequence → RNA" step [1].

A Computational Framework for the Modern Central Dogma

The "Sequence → Structure → Function" paradigm has been formalized in advanced computational models like Life-Code, a unifying framework designed to overcome the "data island" problem of siloed molecular modalities [2].

Life-Code: Unifying Multi-Omics Data

Life-Code implements the modern Central Dogma by redesigning the data and model pipeline:

- Data Flow: A unified pipeline integrates multi-omics data by reverse-transcribing RNA and reverse-translating amino acids into nucleotide-based sequences, grounding all information in the DNA coordinate system [2].

- Model Architecture: A hybrid backbone architecture uses a specialized codon tokenizer and efficient attention mechanisms to handle long biological sequences. It explicitly distinguishes coding (CDS) and non-coding (nCDS) regions, learning through masked language modeling for nCDS and protein translation objectives for CDS [2].

This approach allows the model to capture complex interactions, such as how a genetic variant in DNA might alter RNA splicing and ultimately impact protein structure and function.

Experimental Protocol: The Life-Code Pipeline

Protocol: Implementing the Life-Code Multi-Omics Analysis [2]

- Sequence Input and Unification:

a. DNA Input: Use a DNA sequence

x ∈ Dfrom the reference genome. b. RNA Unification: For an RNA sequencey ∈ R, align it to the genomic DNA to find its originx, using the transcription mapy = T_transcribe(x). c. Protein Unification: For a protein sequencez ∈ P, reverse-translate each amino acid to its canonical codon using the standard genetic code, reconstructing the underlying coding DNA sequence. - Tokenization: Process the unified nucleotide sequences using a codon-level tokenizer, which groups every three nucleotides, preserving the biological meaning of the coding frame.

- Model Pre-training: a. Pre-training Objective: Train the model using a masked language modeling task, where random tokens in the input sequence are masked and the model must predict them. b. Hybrid Attention: Apply a computationally efficient attention mechanism (e.g., linear attention) to the entire sequence, with focused standard attention on key functional regions like promoters and coding sequences.

- Downstream Task Application: Use the pre-trained Life-Code model for specific prediction tasks across DNA, RNA, and protein domains, such as variant effect prediction, protein structure inference, or gene expression level prediction.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The following table details key reagents and materials essential for experimental research in the field of protein engineering and central dogma analysis.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Central Dogma and Protein Engineering Studies

| Research Reagent / Material | Function in Experimental Protocol |

|---|---|

| Poly-A Selection / rRNA Depletion Kits | Isolates mature mRNA from total RNA for mRNA-seq library preparation, enabling accurate transcription analysis. |

| Specific Nuclease (e.g., RNase I) | Digests unprotected mRNA in ribosome profiling, allowing for the isolation of ribosome-protected fragments to measure translation. |

| Crosslinking Reagents (e.g., formaldehyde) | Stabilizes transient molecular interactions in vivo, such as protein-RNA complexes, for techniques like CLIP-seq. |

| Codon-Optimized Synthetic Genes | Gene synthesis designed with host-preferred codons to maximize translation efficiency (high βp) for recombinant protein expression. |

| Tunable Promoter/RBS Libraries | Provides a set of genetic parts (promoters, Ribosomal Binding Sites) of varying strengths to systematically explore Crick space in synthetic biology applications [4]. |

| Mass Spectrometry-Grade Trypsin | Proteolytic enzyme used in bottom-up proteomics to digest proteins into peptides for identification and quantification by mass spectrometry [3]. |

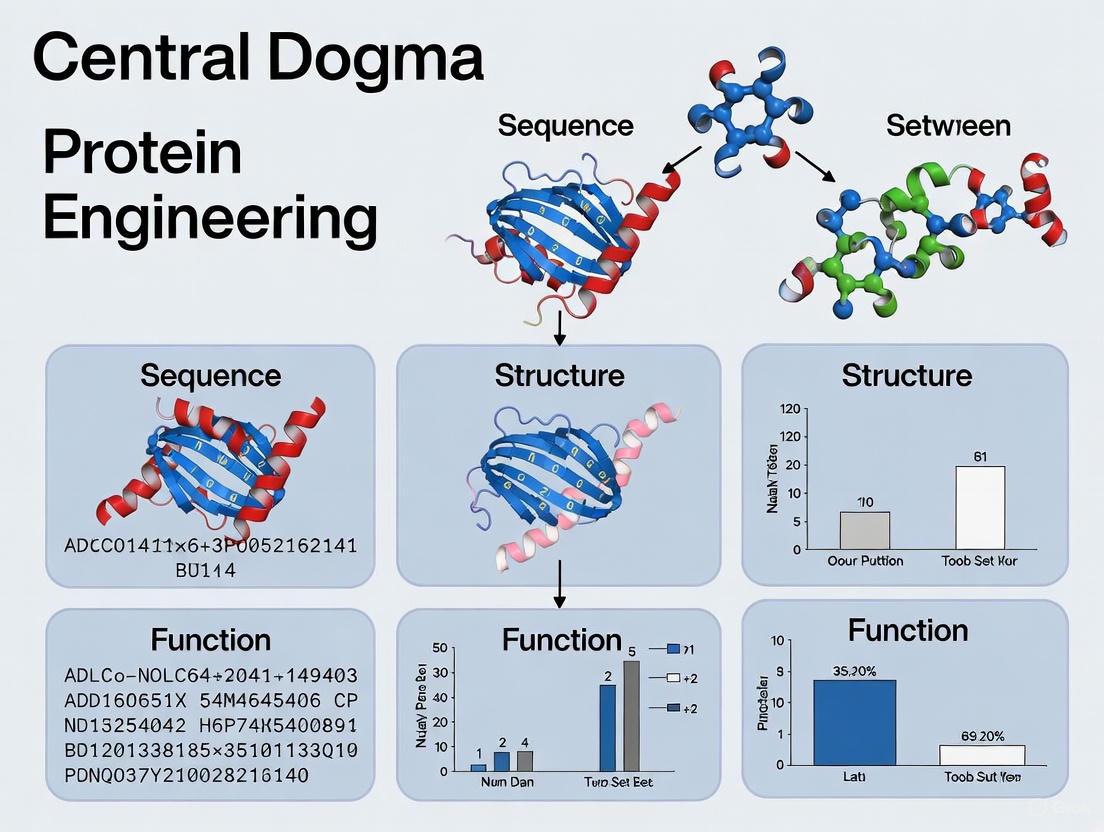

Visualizing the Modern Central Dogma Framework

The following diagram illustrates the core components and their interrelationships within the modern "Sequence → Structure → Function" paradigm, integrating the regulatory influences of non-coding RNAs and environmental factors.

Diagram 1: The Modern Central Dogma integrates core information flow with multi-layered regulation.

The framework of Sequence → Structure → Function constitutes the modern Central Dogma, a sophisticated expansion of Crick's original theorem. It integrates the quantitative rules of gene expression, the regulatory mastery of non-coding RNAs and epigenetics, and the power of unified computational models. This integrated view is fundamental to protein engineering and drug development, providing a roadmap for rationally designing proteins with novel functions, understanding disease mechanisms at a systems level, and developing therapies that can modulate specific nodes within this complex network. The future of biological research and therapeutic innovation lies in leveraging this comprehensive understanding of how genetic information is stored, interpreted, and functionally expressed.

The flow of genetic information from DNA to RNA to protein, enshrined as the central dogma of molecular biology, establishes the fundamental framework for all of life's processes [6] [7]. This sequence of events—where DNA is transcribed into RNA, and RNA is translated into protein—provides the foundational code that determines the structure and function of every cell [7]. In protein engineering, this paradigm is both a guide and a canvas. The field seeks to understand and manipulate the sequence → structure → function relationship to create novel proteins with tailored properties [8]. While the classical view assumes that similar sequences yield similar structures and functions, recent explorations of the protein universe reveal that similar functions can be achieved by different sequences and structures, pushing the boundaries of conventional bioengineering [8]. This whitepaper details the core mechanisms of transcription and translation and examines how they serve as a starting point for advanced research and therapeutic development.

Core Mechanisms: Transcription and Translation

Transcription: DNA to RNA

Transcription is the first step in the actualization of genetic information, the process by which a DNA sequence is copied into a complementary RNA strand [7]. It occurs in the nucleus of eukaryotic cells and involves three key steps:

- Initiation: The enzyme RNA polymerase binds to a specific region of a gene known as the promoter, signaling the DNA to unwind [7].

- Elongation: RNA polymerase reads the template DNA strand and adds complementary RNA nucleotides, building a single-stranded mRNA molecule in the 5' to 3' direction [7].

- Termination: Upon reaching a terminator sequence, RNA polymerase detaches from the DNA, releasing the newly formed pre-mRNA transcript [7].

In eukaryotes, the pre-mRNA undergoes extensive processing before becoming mature mRNA and exiting the nucleus. This includes:

- 5' Capping: Addition of a modified guanine nucleotide to the 5' end, which protects the mRNA and aids ribosomal binding [7].

- Splicing: Removal of non-coding sequences (introns) and joining of coding sequences (exons) [7].

- Polyadenylation: Addition of a poly-A tail (a string of adenine nucleotides) to the 3' end, which also contributes to mRNA stability and export [7].

Translation: RNA to Protein

Translation is the process by which the genetic code carried by mRNA is decoded to synthesize a specific protein. This occurs at ribosomes in the cytoplasm [7]. Transfer RNA (tRNA) molecules act as adaptors, each bearing a specific amino acid and a three-nucleotide anticodon that base-pairs with the corresponding codon on the mRNA. The ribosome facilitates this interaction, catalyzing the formation of peptide bonds between amino acids to form a polypeptide chain. The process also proceeds through three stages:

- Initiation: The small ribosomal subunit, initiator tRNA, and mRNA assemble, followed by the binding of the large ribosomal subunit.

- Elongation: tRNAs deliver amino acids in the sequence specified by the mRNA codons. The ribosome moves along the mRNA, one codon at a time, extending the growing polypeptide chain.

- Termination: When a stop codon is encountered, a release factor binds, prompting the ribosome to dissociate and release the completed protein.

The following diagram illustrates the complete flow of genetic information from DNA to a functional protein.

Central Dogma of Molecular Biology

Quantitative Data in Protein Engineering

Protein engineering relies on quantitative data to link genetic modifications to functional outcomes. Key metrics include thermodynamic stability, binding affinity, and catalytic efficiency, which are essential for evaluating designed proteins.

Table 1: Key Quantitative Metrics in Protein Engineering

| Metric | Symbol | Typical Units | Significance in Protein Engineering |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gibbs Free Energy of Folding | ΔG | kJ/mol | Measures protein stability; more negative values indicate higher stability [9]. |

| Melting Temperature | Tm | °C | Temperature at which 50% of the protein is unfolded; higher Tm indicates greater thermal stability [9]. |

| Dissociation Constant | Kd | M | Measure of binding affinity; lower values indicate tighter binding [9]. |

| Catalytic Rate Constant | kcat | s-1 | Turnover number, the number of substrate molecules converted per enzyme per second [9]. |

| Denaturant Concentration at Unfolding Midpoint | Cm | M (e.g., GdmCl) | Concentration of denaturant at which 50% of the protein is unfolded; indicates resistance to chemical denaturation [9]. |

The interpretation of this data is heavily dependent on the experimental context. Factors such as assay conditions, pH, temperature, and buffer composition must be meticulously recorded to enable valid comparisons across different studies, a principle rigorously upheld by repositories like ProtaBank [9].

From Sequence to Function: Experimental and Computational Methodologies

Computational Prediction and AI in Biology

The complexity of the sequence-structure-function relationship often exceeds the analytical capacity of traditional methods. Machine learning is now being used to pull together higher-order patterns from massive biological datasets [6]. A prime example is the Evo model series.

Table 2: Overview of the Evo Model Series for Biological Sequence Analysis

| Feature | Evo 1 (2024) | Evo 2 (2025) |

|---|---|---|

| Training Data | Trained entirely on single-celled organisms [6]. | 9.3 trillion nucleotides; 128,000 whole genomes from ~100,000 species across the tree of life [6]. |

| Model Capabilities | Foundational model for biological sequence analysis. | Classifies pathogenicity of mutations (e.g., >90% accuracy on BRCA1); predicts essential genes and causal disease mechanisms [6]. |

| Technical Specs | A large language model for biological sequences. | Processes up to 1 million nucleotides at once; uses nucleotide "tokens" (A, C, G, T/U) to predict sequences and biological properties [6]. |

The workflow for large-scale structure-function analysis, as used to map the microbial protein universe, is outlined below.

Workflow for Mapping Protein Universe

Engineering Protein Switches and Biosensors

A major goal in protein engineering is creating switches where protein activity is controlled by a specific input, such as ligand binding [10]. The general strategy involves fusing an input domain (which recognizes the trigger) to an output domain (which produces the biological response). For DNA-sensing switches, the input domain is often an oligonucleotide-recognition module [10].

Protocol: Creating a DNA-Activated Biosensor via Alternate Frame Folding

- Selection of Domains: Choose a DNA-binding protein (e.g., GCN4) as the input domain and a reporter enzyme (e.g., nanoluciferase, nLuc) as the output domain [10].

- Insertion and Fusion: Insert the gene encoding the input domain into a surface-exposed loop of the output domain gene. This creates a single open reading frame for the chimeric protein [10].

- Library Construction: Use techniques like circular permutation or random linkers to generate a library of constructs where the insertion site and linker sequences are varied [10].

- Functional Screening: Express the library and screen for clones where the luminescent output (from nLuc) is minimal in the absence of the target DNA and significantly increases upon DNA binding. This indicates a successful coupling of binding to activation [10].

- Characterization: Purify the positive hits and quantify key performance metrics, including the limit of detection, dynamic range, and specificity for the target DNA sequence over non-target sequences [10].

Advancing protein engineering research requires a suite of specialized reagents, databases, and computational tools.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Protein Engineering

| Reagent / Resource | Function / Application | Specifications / Examples |

|---|---|---|

| ProtaBank | A centralized repository for storing, querying, and sharing protein engineering data, including mutational stability, binding, and activity data [9]. | Accommodates data from rational design, directed evolution, and deep mutational scanning; enforces full-sequence storage for accurate comparison [9]. |

| Evo 2 Model | A machine learning model for predicting the functional impact of genetic variations and guiding target identification [6]. | Trained on 9.3 trillion nucleotides; can classify variant pathogenicity with high accuracy and predict causal disease relationships [6]. |

| Nanoluciferase (nLuc) | A small, bright, and stable luminescent output domain for biosensor engineering, enabling highly sensitive detection [10]. | From Oplophorus gracilirostris; 171 residues; catalyzes furimazine oxidation to emit blue light; used in BRET-based assays [10]. |

| CRISPR/dCas9 Actvators | Engineered transcriptional machinery for programmable gene activation in functional genomics and therapeutic development [11]. | Systems like SAM (Synergistic Activation Mediator); novel activators like MHV and MMH show enhanced potency and reduced toxicity [11]. |

| DNA Shuffling Tools | Protocols and methods for in vitro directed evolution to recombine beneficial mutations and optimize protein function [12]. | Described in Protein Engineering Protocols; used to mimic natural recombination and evolve improved protein variants [12]. |

Transcription and translation are more than just the core mechanisms of the central dogma; they are the foundational processes from which modern protein engineering emerges. By leveraging advanced computational models like Evo, robust databases like ProtaBank, and sophisticated design strategies such as alternate frame folding, researchers are moving beyond observation to causation. This allows for the rational design of proteins with novel functions, from highly specific biosensors for point-of-care diagnostics to potent and safe CRISPR-based activators for therapeutic intervention. The continued integration of AI, large-scale experimental data, and precise molecular biology techniques will further decouple the sequence-structure-function relationship, enabling the engineering of biological solutions to some of medicine's most persistent challenges.

How Protein Sequence Dictates 3D Structure and Biological Activity

The fundamental paradigm in molecular biology, often termed the sequence-structure-function relationship, posits that a protein's amino acid sequence dictates its unique three-dimensional structure, which in turn determines its specific biological activity. This principle forms the cornerstone of structural biology and modern protein engineering. With the advent of advanced computational models and high-throughput experimental methods, our understanding of this relationship has deepened significantly, enabling the precise prediction of protein structures from sequences and the rational design of novel protein functions. This technical guide examines the current state of research on how protein sequence governs 3D structure formation and biological activity, with particular emphasis on revolutionary deep learning approaches, experimental validation methodologies, and therapeutic applications relevant to drug development professionals.

Fundamental Principles of Sequence-to-Structure Relationship

The Thermodynamic and Evolutionary Basis

The folding of a protein from a linear amino acid chain into a specific three-dimensional structure is governed by both thermodynamic principles and evolutionary constraints. The amino acid sequence encodes the information necessary to guide this folding process through a complex balance of molecular interactions, including hydrogen bonding, van der Waals forces, electrostatic interactions, and hydrophobic effects. These interactions collectively drive the polypeptide chain toward its native conformation, which represents the global free energy minimum under physiological conditions.

Evolution has shaped protein sequences to optimize this folding process, resulting in structural conservation even when sequences diverge significantly. This conservation is particularly evident at the structural level of protein-protein interactions, where interaction interfaces tend to be more conserved than sequence motifs. Extensive experimental evidence suggests that the repertoire of protein interaction modes in nature is remarkably limited, with similar structural binding patterns observed across diverse protein-protein interactions [13].

Challenges to the Traditional Paradigm

While the sequence→structure→function paradigm remains a foundational concept, certain protein regions defy this constraint, with protein activity dictated more by amino acid composition than precise primary sequence. These composition-driven protein activities are often associated with intrinsically disordered regions (IDRs) and low-complexity domains (LCDs) that do not adopt stable 3D structures yet perform crucial biological functions [14].

For well-folded proteins, even slight changes to primary amino acid sequence can substantially affect function, and they often exhibit primary-sequence conservation across organisms. In contrast, IDRs evolve faster than structured regions and can diverge considerably while maintaining activity. Some IDRs retain activity simply by conserving amino acid composition despite substantial primary-sequence divergence [14].

Computational Methods for Structure Prediction and Validation

Revolution in Structure Prediction Through Deep Learning

Recent breakthroughs in deep learning have dramatically advanced our ability to predict protein structures from amino acid sequences with experimental accuracy. AlphaFold2, recognized for its revolutionary performance in CASP14, employs an Evoformer architecture that refines evolutionary information from multiple sequence alignments and structural template searches to determine final protein structures [15]. The system has been extended to protein complex prediction with AlphaFold-Multimer and the more recent AlphaFold3, which can predict various biomolecular interactions with high accuracy through a simplified MSA representation and diffusion module for predicting raw atom coordinates [13] [15].

Similar to AlphaFold2, RoseTTAFold uses a three-track network that integrates information from amino acid sequences, distance maps, and 3D coordinates. Its recent extension, RoseTTAFold All-Atom, incorporates information on chemical element types of non-polymer atoms, chemical bonds, and chirality, enabling prediction of diverse biomolecular structures [15].

Advanced Methods for Protein Complex Prediction

Predicting the quaternary structure of protein complexes presents significantly greater challenges than monomer prediction, as it requires accurate modeling of both intra-chain and inter-chain residue-residue interactions. DeepSCFold represents a notable advancement in this area, using sequence-based deep learning models to predict protein-protein structural similarity and interaction probability. This pipeline constructs deep paired multiple-sequence alignments for protein complex structure prediction, achieving an improvement of 11.6% and 10.3% in TM-score compared to AlphaFold-Multimer and AlphaFold3, respectively, on CASP15 multimer targets [13].

For antibody-antigen complexes, which often lack clear co-evolutionary signals, DeepSCFold enhances prediction success rates for binding interfaces by 24.7% and 12.4% over AlphaFold-Multimer and AlphaFold3, respectively, demonstrating its ability to capture intrinsic protein-protein interaction patterns through sequence-derived structure-aware information [13].

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Protein Structure Prediction Methods

| Method | Type | Key Features | Reported Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| AlphaFold2 | Monomer structure prediction | Evoformer architecture, MSA processing | CASP14 top-ranked method; accuracy competitive with experiments [16] [15] |

| AlphaFold3 | Complex structure prediction | Simplified MSA, diffusion module | Predicts various biomolecules; outperformed by DeepSCFold on complexes [13] [15] |

| RoseTTAFold | Monomer structure prediction | Three-track network | Accuracy comparable to AlphaFold2 [15] |

| DeepSCFold | Complex structure prediction | Sequence-derived structure complementarity | 11.6% improvement in TM-score over AlphaFold-Multimer on CASP15 targets [13] |

| trRosettaX-Single | Orphan protein prediction | MSA-free algorithm | Superior to AlphaFold2 and RoseTTAFold for orphan proteins [15] |

Protein Language Models and Function Prediction

Inspired by successes in natural language processing, protein language models (PLMs) have emerged as powerful tools for extracting functional information directly from sequences. These models, including ESM 1b and ESM3, utilize transformer architectures pre-trained on millions of protein sequences to learn evolutionary patterns and structural constraints [17]. PLMs have demonstrated remarkable performance in predicting protein function, often outperforming traditional methods in the Critical Assessment of Function Annotation (CAFA) challenges.

ESM3 represents a significant advancement as a multimodal generative language model capable of learning joint distributions over protein sequence, structure, and function simultaneously. This enables programmable protein design through a "chain-of-thought" approach across modalities, though it does not generate multiple modalities simultaneously [18].

Experimental Methodologies for Validation

Assessing Composition-Driven Activities

For composition-driven activities, experimental validation often involves testing whether scrambling the protein's primary sequence abolishes function. A hallmark of composition dependence is the maintenance of protein activity upon repeated scrambling while preserving amino acid composition. In practice, the distribution of activity levels for scrambled variants tends to be higher than when the domain is deleted entirely or replaced with an inactive domain [14].

Deep mutational scanning (DMS) provides a high-throughput approach to systematically assess how sequence variations affect structure and function. By generating and screening large libraries of protein variants, researchers can map sequence-activity relationships and identify critical residues for folding, stability, and function [14].

Platforms for Structural Analysis

Integrated platforms like DPL3D provide comprehensive tools for predicting and visualizing 3D structures of mutant proteins. This platform incorporates multiple prediction tools including AlphaFold 2, RoseTTAFold, RoseTTAFold All-Atom, and trRosettaX-Single, alongside advanced visualization capabilities. It includes query services for over 210,000 molecular structure entries, including 54,332 human proteins, enabling researchers to quickly access structural information for biological discovery [15].

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Protein Structure-Function Studies

| Research Reagent/Platform | Function/Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|

| DPL3D Platform | Protein structure prediction and visualization | Integrates AlphaFold 2, RoseTTAFold, RoseTTAFold All-Atom, trRosettaX-Single; 210,180 structure entries [15] |

| AlphaFold Database | Access to pre-computed protein structures | Over 200 million protein structure predictions; covers most of UniProt [16] |

| OrthoRep Continuous Evolution System | Protein engineering through directed evolution | Enables growth-coupled evolution for proteins with diverse functionalities [19] |

| Synthetic Gene Circuits | Tunable gene expression in human cells | Permits precise control of gene expression from completely off to completely on [20] |

| Deep Mutational Scanning (DMS) | High-throughput functional characterization | Systematically assesses how sequence variations affect protein function [14] |

Protein Design and Engineering Applications

Generative Models for Protein Design

Generative artificial intelligence has opened new frontiers in protein design by enabling the creation of novel protein sequences and structures with desired functions. Diffusion models, including JointDiff and JointDiff-x, implement a unified architecture that simultaneously models amino acid types, positions, and orientations through dedicated diffusion processes. These models represent each residue by three distinct modalities (type, position, and orientation) and employ a shared graph attention encoder to integrate multimodal information [18].

While these joint sequence-structure generation models currently lag behind two-stage approaches in sequence quality and motif scaffolding performance based on computational metrics, they are 1-2 orders of magnitude faster and support rapid iterative improvements through classifier-guided sampling. Experimental validation of jointly designed green fluorescent protein (GFP) variants has confirmed measurable fluorescence, demonstrating the functional potential of this approach [18].

Automated Laboratory Platforms

Industrial automated laboratories represent the cutting edge in protein engineering, enabling continuous and scalable protein evolution. The iAutoEvoLab platform features high throughput, enhanced reliability, and minimal human intervention, operating autonomously for approximately one month. This system integrates new genetic circuits for continuous evolution systems to achieve growth-coupled evolution for proteins with complex functionalities [19].

Such platforms have been used to evolve proteins from inactive precursors to fully functional entities, such as a T7 RNA polymerase fusion protein CapT7 with mRNA capping properties, which can be directly applied to in vitro mRNA transcription and mammalian systems [19].

Visualization of Methodologies

Workflow for Protein Structure-Function Analysis

The following diagram illustrates the integrated computational and experimental workflow for analyzing how protein sequence dictates 3D structure and biological activity:

Protein Sequence-Structure-Function Relationship Spectrum

The relationship between protein sequence, structure, and function exists on a spectrum from strict dependence on primary sequence to composition-driven activities:

The fundamental relationship between protein sequence, structure, and function continues to be elucidated through integrated computational and experimental approaches. Deep learning models have revolutionized our ability to predict structures from sequences, while advanced experimental methods enable high-throughput validation and engineering of novel protein functions.

Future research directions will likely focus on improving multimodal generative models for joint sequence-structure-function design, enhancing prediction accuracy for protein complexes and membrane proteins, and developing more sophisticated automated laboratory systems for continuous protein evolution. As these technologies mature, they will accelerate drug discovery and development by enabling more precise targeting of disease mechanisms and engineering of therapeutic proteins with optimized properties.

The integration of protein language models, diffusion-based generative architectures, and automated experimental validation represents a powerful paradigm for advancing both fundamental understanding and practical applications of the sequence-structure-function relationship. This integrated approach will continue to drive innovations in protein engineering and therapeutic development for years to come.

The central dogma of molecular biology describes the fundamental flow of genetic information from DNA sequence to RNA transcript to functional protein, where function is the final outcome of a linear process [2]. In contrast, the paradigm of modern protein engineering seeks to invert this flow, beginning with a precisely defined desired function and working backward to design an optimal amino acid sequence that will achieve it [21]. This reverse-engineering goal represents a cornerstone of contemporary biotechnology, enabling the creation of novel enzymes, therapeutics, and biosensors with tailor-made properties.

This inversion rests on a critical intermediary: protein structure. The classic understanding of protein biochemistry posits that a sequence folds into a single, stable three-dimensional structure, which in turn dictates its biological function [22]. Therefore, the core challenge in reversing the central dogma lies in first determining a protein structure capable of executing the desired function, and then identifying a sequence that will reliably fold into that specific structure [21]. This process, known as the "sequence → structure → function" paradigm, underpins nearly all de novo protein design efforts, transforming protein engineering from a discovery-based science into a predictive and creative discipline [21].

Computational Methodologies for Structure and Sequence Design

The computational arm of protein engineering has been revolutionized by deep learning, which provides the tools to navigate the vast sequence and structure spaces.

Protein Structure Prediction

Accurate prediction of a protein's three-dimensional structure from its amino acid sequence is a foundational capability. Deep learning has dramatically advanced this field, moving from homology-based methods to ab initio and template-free modeling. These approaches leverage large language models trained on known protein structures from databases like the Protein Data Bank (PDB) to predict the spatial arrangement of amino acid residues with remarkable accuracy [22].

Table 1: Key Deep Learning Approaches for Protein Structure Prediction

| Method Category | Representative Tools | Core Principle | Key Input Data | Best-Suited Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Template-Based Modeling (TBM) | MODELLER, SwissPDBViewer [22] | Uses known protein structures as templates for a target sequence with significant homology. | Target sequence, homologous template structure(s). | Predicting structures with high sequence identity (>30%) to known templates. |

| Template-Free Modeling (TFM) | AlphaFold, TrRosetta [22] | Predicts structure directly from sequence using AI, without explicit global templates, though trained on PDB data. | Target sequence, Multiple Sequence Alignments (MSAs). | Predicting novel protein folds or proteins with low homology to known structures. |

| Ab Initio | Various research tools [22] | Based purely on physicochemical principles and energy minimization, without relying on existing structural data. | Amino acid sequence and physicochemical properties. | True de novo folding simulations; useful when no homologous structures exist. |

From Target Structure to Optimal Sequence

Once a target structure is defined, the next step is finding sequences that stabilize it. This involves searching the vast sequence space for candidates that possess the right physicochemical properties to fold into the desired conformation.

Table 2: Computational Methods for Sequence Design

| Method | Underlying Principle | Key Advantage | Inherent Challenge |

|---|---|---|---|

| Physics-Based Energy Minimization | Uses force fields to calculate and minimize the free energy of a sequence in the target structure. | Grounded in fundamental physicochemical principles. | Computationally intensive; force fields may be imperfect. |

| Machine Learning-Guided Design | Employs models trained on protein databases to predict which sequences are compatible with a fold. | Rapidly explores sequence space; learns from natural protein rules. | Model performance is dependent on the quality and breadth of training data. |

| Sequence-Structure Co-Design | Simultaneously optimizes both sequence and structure, rather than as separate sequential steps. | Allows for flexibility and mutual adjustment between sequence and structure. | Increases the complexity of the optimization landscape. |

Experimental Realization: Continuous Evolution and Automated Laboratories

Computational predictions require experimental validation and refinement. Recent advances have automated and accelerated this process through continuous evolution systems and self-driving laboratories.

Platforms like OrthoRep enable continuous directed evolution by creating a tight link between a protein's function and its host organism's growth rate [19]. This growth-coupled selection allows for the autonomous exploration of sequence space, pushing proteins toward improved or novel functions over generations without human intervention [19]. Furthermore, the integration of such evolution systems into fully automated laboratories, such as the iAutoEvoLab, allows for continuous and scalable protein evolution. These systems can operate autonomously for extended periods (e.g., ~1 month), systematically exploring protein fitness landscapes to discover functional variants [19].

These automated platforms can implement sophisticated genetic circuits to select for complex functionalities. For instance, a NIMPLY logic circuit was used to successfully evolve the transcription factor LmrA for enhanced operator selectivity, demonstrating the ability to select for specific, non-growth-related functional properties [19].

Integrated Experimental Protocol: Evolving a Functional Protein from an Inactive Precursor

The following detailed methodology, inspired by the workflow of automated evolution labs, outlines the key steps for evolving a functional protein from an inactive starting sequence [19].

Step 1: Define Functional Goal and Selection Strategy

- Clearly articulate the desired protein function (e.g., binding affinity, enzymatic activity, spectral property).

- Design a genetic selection or screen that links the desired function to a measurable output, such as cell survival, fluorescence, or antibiotic resistance. For complex functions, this may require sophisticated circuits like dual-selection or NIMPLY logic gates [19].

Step 2: Construct Diversity Library

- Starting Point: Begin with an inactive precursor or a low-activity scaffold protein.

- Library Generation: Introduce genetic diversity through error-prone PCR, DNA shuffling, or synthetic oligonucleotide libraries to create a vast pool of sequence variants.

Step 3: Implement Continuous Evolution System

- Platform: Employ a continuous evolution system (e.g., OrthoRep in yeast or PACE in bacteria) [19].

- Coupling: Clone the variant library into the system such that the desired protein function is linked to the propagation of its encoding genetic element (e.g., a plasmid or phage genome).

Step 4: Automate and Monitor Evolution

- Automation: Integrate the evolution system into an automated platform capable of continuous culturing, sampling, and environmental modulation (e.g., using eVOLVER or similar systems) [19].

- Process: Allow the system to run autonomously. Host cells harboring beneficial mutations will outcompete others, enriching the population for functional protein sequences over successive generations.

Step 5: Isolation and Validation

- Sampling: Periodically sample the population from the evolution vessel.

- Screening: Isolate individual clones and subject them to secondary assays to confirm the function and characterize the improved protein (e.g., measure activity, specificity, and expressibility).

- Sequence Analysis: Sequence the genes of the top-performing variants to identify the mutations responsible for the gained function.

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the core conceptual and experimental workflow for reversing the central dogma in protein engineering.

Diagram 1: The core paradigm of reverse protein engineering, moving from desired function to optimal sequence via computational and experimental cycles.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Reagents for Protein Engineering

| Tool / Reagent | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| OrthoRep System [19] | A continuous in vivo evolution platform in yeast. It uses an orthogonal DNA polymerase-plasmid pair to create a high mutation rate specifically on the target gene, enabling rapid evolution. |

| PACE (Phage-Assisted Continuous Evolution) [19] | A continuous in vivo evolution system in bacteria. It links protein function to phage propagation, allowing for dozens of rounds of evolution to occur in a single day with minimal manual intervention. |

| Automated Cultivation Systems (e.g., eVOLVER) [19] | Scalable, automated bioreactors that allow for precise, high-throughput control of growth conditions (e.g., temperature, media) for hundreds of cultures in parallel, facilitating massive evolution experiments. |

| Pre-trained Protein Language Models (e.g., ESM, AlphaFold) [2] [22] | Deep learning models pre-trained on millions of protein sequences and/or structures. They can be fine-tuned for tasks like structure prediction, variant effect prediction, and generating novel, foldable sequences. |

| Genetic Circuits (e.g., NIMPLY, Dual Selection) [19] | Synthetic biological circuits implemented in the host organism. They enable selection for complex, multi-faceted functions that are not directly tied to survival, such as high specificity or logic-gated behavior. |

The central dogma of protein engineering encapsulates the fundamental principle that a protein's amino acid sequence determines its three-dimensional structure, which in turn dictates its function [23]. This sequence-structure-function relationship serves as the foundational framework for efforts to understand, predict, and design protein activity. While this paradigm has guided biological research for decades, the protein engineering landscape is now being transformed by two simultaneous revolutions: the explosive growth of biological data and the integration of sophisticated artificial intelligence (AI) methodologies [23] [24]. These developments are rapidly shifting the field from a predominantly experimental discipline to one that increasingly relies on computational prediction and design.

However, significant challenges persist in accurately mapping the intricate relationships between sequence variation, structural conformation, and functional output. Researchers now recognize that the sequence-structure-function pathway is not always a linear, deterministic process [25]. This technical guide examines the key challenges in navigating this complex landscape, surveys cutting-edge computational and experimental approaches to address them, and provides practical methodologies for researchers working in drug development and protein engineering.

Core Challenges in the Sequence-Structure-Function Relationship

Limitations of the Central Dogma in Practical Applications

The conventional understanding of the central dogma assumes that increasing the expression of a gene's RNA transcript will reliably lead to increased production and secretion of the corresponding protein. However, recent research challenges this assumption. A UCLA study on mesenchymal stem cells revealed a surprisingly weak correlation between VEGF-A gene expression and actual protein secretion levels, indicating that post-transcriptional factors and cellular machinery significantly modulate protein output [25]. This finding has profound implications for biotechnological applications where cells are engineered as protein-producing factories, suggesting that focusing solely on gene expression may be insufficient for optimizing protein secretion.

Additionally, the interpretation of Anfinsen's dogma – that a protein's native structure is determined solely by its sequence under thermodynamic control – faces limitations when applied to static computational predictions. Proteins exist as dynamic ensembles of conformations, particularly in flexible regions or intrinsically disordered segments, which current AI methods struggle to capture accurately [26]. This simplification becomes especially problematic for proteins whose functional conformations are influenced by their thermodynamic environment or interactions with binding partners [26].

Data Scarcity and the High-Order Mutant Problem

A significant bottleneck in protein engineering is the limited availability of experimental data for training predictive models, particularly for high-order mutants (variants with multiple amino acid substitutions). Supervised deep learning models generally outperform unsupervised approaches but require substantial amounts of experimental mutation data – often hundreds to thousands of data points per protein – which is experimentally challenging and costly to generate [24]. This data scarcity becomes particularly acute for high-order mutants, which often represent the most promising candidates for therapeutic applications but require exponentially more screening capacity [24].

Table 1: Key Challenges in Protein Sequence-Structure-Function Prediction

| Challenge | Impact | Current Status |

|---|---|---|

| Data Scarcity for High-Order Mutants | Limits accurate fitness prediction for multi-site variants | Supervised models require 100s-1000s of data points; experimental screening remains costly [24] |

| Static Structure Prediction | Inadequate representation of dynamic protein conformations | AI models produce static snapshots; fail to capture functional flexibility [26] |

| Complex Structure Prediction | Reduced accuracy for multi-chain complexes | AlphaFold-Multimer accuracy lower than monomer predictions [13] |

| Weak Correlation Gene Expression-Protein Secretion | Challenges biotechnological protein production | UCLA study showed weak link between VEGF-A gene expression and secretion [25] |

Computational Limitations in Structure Prediction

Despite revolutionary advances in AI-based protein structure prediction, recognized by the 2024 Nobel Prize in Chemistry, significant limitations remain. Current methods face particular challenges with protein complexes and dynamic conformations [26]. For example, AlphaFold-Multimer achieves considerably lower accuracy for multimer structures compared to AlphaFold2's performance on monomeric proteins [13]. This represents a critical limitation since most proteins function as complexes rather than isolated chains in biological systems.

The problem is particularly pronounced for certain classes of interactions, such as antibody-antigen complexes, where traditional co-evolutionary signals may be weak or absent [13]. These systems often lack clear sequence-level co-evolution because identifying orthologs between host and pathogenic proteins is challenging due to the absence of species overlap [13]. This necessitates alternative approaches that can capture structural complementarity beyond direct evolutionary relationships.

Advanced Computational Approaches

Integrated Sequence-Structure Deep Learning Models

To address the limitations of single-modality approaches, researchers have developed integrated models that leverage both sequence and structure information. SESNet represents one such advanced framework that combines three complementary encoder modules: a local encoder derived from multiple sequence alignments (MSA) capturing residue interdependence from homologous sequences; a global encoder from protein language models capturing features from universal protein sequence space; and a structure module capturing 3D geometric microenvironments around each residue [24].

This integrated approach demonstrates superior performance in predicting the fitness of protein variants, particularly for higher-order mutants. On 26 deep mutational scanning datasets, SESNet outperformed state-of-the-art models including ECNet, ESM-1b, ESM-1v, ESM-IF1, and MSA transformer [24]. The model's architecture enables it to learn the sequence-function relationship more effectively by leveraging both evolutionary information and structural constraints.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Protein Engineering Models

| Model | Type | Key Features | Performance Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| SESNet | Supervised | Integrates local MSA, global language model, and structure module | Outperforms other models on 26 DMS datasets; excels with high-order mutants [24] |

| ECNet | Supervised | Evolutionary model coupled with supervised learning | Generally outperforms unsupervised models but requires large experimental datasets [24] |

| ESM-1b/ESM-1v | Unsupervised/Language Model | Learns from universal protein sequences without experimental labels | Lower performance than supervised models but doesn't require experimental data [24] |

| DeepSCFold | Complex Prediction | Uses sequence-derived structure complementarity for complexes | 11.6% improvement in TM-score over AlphaFold-Multimer on CASP15 targets [13] |

| AlphaFold-Multimer | Complex Prediction | Adapted from AlphaFold2 for multimers | Lower accuracy than monomeric AlphaFold2; challenges with antibody-antigen interfaces [13] |

Data-Efficient Learning Strategies

To overcome the data scarcity problem, particularly for high-order mutants, researchers have developed innovative data augmentation strategies. One effective approach involves pretraining models on large quantities of lower-quality data derived from unsupervised models, followed by fine-tuning with small amounts of high-quality experimental data [24]. This strategy significantly reduces the experimental burden while maintaining high prediction accuracy.

Remarkably, with this approach, models can achieve striking accuracy in predicting the fitness of protein variants with more than four mutation sites when fine-tuned with as few as 40 experimental measurements [24]. This makes the approach particularly valuable for practical protein engineering applications where extensive experimental screening may be prohibitively expensive or time-consuming.

Leveraging Structural Complementarity

For protein complex prediction, new methods like DeepSCFold address the limitations of traditional co-evolution-based approaches by incorporating structural complementarity information derived directly from sequence data. DeepSCFold uses deep learning to predict protein-protein structural similarity (pSS-score) and interaction probability (pIA-score) from sequence information alone, enabling more accurate construction of paired multiple sequence alignments for complex structure prediction [13].

This approach has demonstrated significant improvements, achieving 24.7% and 12.4% enhancement in success rates for antibody-antigen binding interface prediction compared to AlphaFold-Multimer and AlphaFold3, respectively [13]. By capturing conserved structural interaction patterns that may not be evident at the sequence level, these methods open new possibilities for modeling challenging complexes.

Experimental Methods and Validation

Single-Cell Secretion Analysis

The UCLA challenge to the central dogma employed innovative experimental methodology based on nanovial technology – microscopic bowl-shaped hydrogel containers that capture individual cells and their secretions [25]. This platform enabled researchers to correlate protein secretion profiles with gene expression patterns at single-cell resolution, revealing the disconnect between VEGF-A gene expression and protein secretion in mesenchymal stem cells.

The experimental workflow involved:

- Single-Cell Encapsulation: Mesenchymal stem cells were individually captured in nanovials along with antibody-coated beads to capture secreted VEGF-A.

- Secretion Profiling: VEGF-A secretion was quantified for each cell via fluorescence labeling.

- Cell Sorting: Cells were sorted based on secretion levels using fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS).

- Transcriptome Analysis: Single-cell RNA sequencing was performed on sorted cells to correlate gene expression with secretion profiles.

This approach identified novel surface markers, such as IL13RA2, that correlated strongly with VEGF-A secretion. Cells with this marker showed 30% higher VEGF-A secretion initially and 60% higher secretion after six days in culture [25].

Deep Mutational Scanning

Deep Mutational Scanning (DMS) represents a key experimental methodology for generating fitness landscapes of protein variants. This approach involves:

- Library Construction: Creating a diverse library of protein variants through mutagenesis.

- Functional Selection: Applying selective pressure based on desired protein function.

- High-Throughput Sequencing: Quantifying variant abundance before and after selection.

- Fitness Calculation: Determining the functional impact of each mutation based on enrichment/depletion.

DMS datasets provide crucial training data for supervised learning models and validation benchmarks for computational methods [24]. These experiments have been applied to various protein functionalities, including catalytic rate, stability, binding affinity, and fluorescence intensity [24].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Protein Engineering

| Tool/Reagent | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Nanovials | Single-cell analysis platform | Correlating protein secretion with gene expression [25] |

| Deep Mutational Scanning Libraries | Protein variant fitness profiling | Generating sequence-function training data [24] |

| Protein Language Models (ESM) | Sequence representation learning | Zero-shot mutation effect prediction [23] [24] |

| AlphaFold-Multimer | Protein complex structure prediction | Modeling quaternary structures [13] |

| Rosetta & DMPfold | De novo structure prediction | Modeling novel folds without templates [8] |

| DeepSCFold | Complex structure modeling | Predicting antibody-antigen interfaces [13] |

| SESNet | Fitness prediction | High-order mutant effect prediction [24] |

| World Community Grid | Distributed computing | Large-scale structure prediction [8] |

The field of protein engineering is undergoing rapid transformation driven by computational advances, yet fundamental challenges remain in fully capturing the complexity of the sequence-structure-function relationship. Future progress will likely depend on several key developments: better integration of protein dynamics into structural models, improved handling of multi-chain complexes, and more effective bridging of the gap between in silico predictions and cellular implementation [26] [25].

The discovery that gene expression does not necessarily correlate with protein secretion highlights the need for more sophisticated models that incorporate cellular context and post-translational processes [25]. Similarly, the limitations of current AI methods in capturing functional conformations underscore the importance of developing dynamic rather than static structural representations [26].

As these challenges are addressed, the potential for computational protein engineering to accelerate therapeutic development remains immense. By combining increasingly powerful AI models with targeted experimental validation, researchers can navigate the vast sequence-structure-function landscape more effectively, opening new possibilities for drug development, enzyme design, and synthetic biology.

Computational and Experimental Tools for Designing Functional Proteins

Rational protein design represents a paradigm shift in molecular biology, enabling the creation of novel protein structures and functions through computational approaches that inverse the traditional sequence-structure-function relationship. This technical guide examines structure-based computational modeling methodologies that leverage physical principles and algorithmic optimization to design proteins with predetermined characteristics. By integrating quantum mechanical calculations, molecular mechanics force fields, and sophisticated search algorithms, researchers can now engineer proteins with novel catalytic activities, enhanced stability, and customized molecular recognition properties. This whitepaper comprehensively reviews the computational frameworks, experimental validation protocols, and emerging applications in biotechnology and therapeutics, providing researchers with both theoretical foundations and practical methodologies for advancing protein engineering initiatives.

Rational protein design establishes a direct pathway from desired function to molecular implementation by leveraging computational modeling to identify amino acid sequences that will fold into specific three-dimensional structures capable of performing target functions [27]. This approach inverts the classical central dogma of molecular biology - which describes the unilateral flow of genetic information from DNA to RNA to protein - by starting with a target protein structure and working backward to identify sequences that will achieve it [28] [29]. Where natural evolution and traditional protein engineering rely on stochastic variation and screening, rational design employs computational prediction to precisely determine sequences that satisfy structural and functional constraints before experimental implementation [30].

The foundational principle of rational protein design rests on the structure-function relationship in proteins, where three-dimensional structure dictates biological activity. Computational protein design programs must solve two fundamental challenges: accurately evaluating how well a particular amino acid sequence fits a given scaffold through scoring functions, and efficiently searching the vast sequence-conformation space to identify optimal solutions [27] [31]. This process constitutes a rigorous test of our understanding of protein folding and function - successful design validates the completeness of our knowledge, while failures reveal gaps in our understanding of the physical forces governing protein structure [30].

Computational Frameworks and Methodologies

Fundamental Components of Protein Design Algorithms

Computational protein design platforms incorporate four essential elements: (1) a target structure or structural ensemble, (2) defined sequence space constraints, (3) models of structural flexibility, and (4) energy functions for evaluating sequence-structure compatibility [31]. These components work in concert to navigate the immense combinatorial complexity of protein sequence space and identify solutions that stabilize the target fold.

Target Structure Specification: The process begins with selection of a protein backbone that will support the desired function. This may be derived from natural proteins or created de novo using algorithms that generate novel folds [31]. For example, the Top7 protein developed in David Baker's laboratory demonstrated the feasibility of designing entirely new protein folds not observed in nature [31].

Sequence Space Definition: The possible amino acid substitutions at each position must be constrained to make the search problem tractable. In protein redesign, most residues maintain their wild-type identity while a limited subset is allowed to mutate. In de novo design, the entire sequence is variable but subject to composition constraints [31].

Structural Flexibility Modeling: To increase the number of sequences compatible with the target fold, design algorithms incorporate varying degrees of structural flexibility. Side-chain flexibility is typically modeled using rotamer libraries - collections of frequently observed low-energy conformations - while backbone flexibility may be introduced through small continuous movements, discrete sampling around the target fold, or loop flexibility models [31].

Energy Functions: Scoring functions evaluate sequence-structure compatibility using physics-based potentials (adapted from molecular mechanics programs like AMBER and CHARMM), knowledge-based statistical potentials derived from protein structure databases, or hybrid approaches [31]. The Rosetta energy function, for instance, incorporates both physics-based terms from CHARMM and statistical terms such as rotamer probabilities and knowledge-based electrostatics [31].

Key Algorithms and Their Applications

Table 1: Computational Protein Design Algorithms and Their Applications

| Algorithm | Methodological Approach | Primary Applications | Representative Successes |

|---|---|---|---|

| ROSETTA | Monte Carlo optimization with combinatorial sequence-space search | De novo enzyme design, protein-protein interface design, membrane protein design | Kemp eliminases, retro-aldolases, designed protein-protein interactions [27] [32] |

| K* Algorithm | Continuous optimization of side-chain conformations with backbone flexibility | Metalloprotein design, thermostability engineering | Designed metalloenzymes with novel coordination geometries [27] |

| DEZYMER/ORBIT | Fixed-backbone design with rigid body docking | Active site grafting, functional site design | Introduction of triose phosphate isomerase activity into thioredoxin scaffold [27] |

| Dead-End Elimination | Combinatorial optimization that eliminates high-energy conformations | Protein core redesign, specificity switching | Repacked cores of protein G B1 domain with improved stability [27] [30] |

| FRESCO | Computational library design and in silico screening | Enzyme thermostabilization | Stabilized enzymes with >20°C improvement in melting temperature [32] |

Active Site Design and Functional Engineering

The design of functional proteins requires precise positioning of catalytic residues and cofactors to enable chemical transformations. De novo active site design implements quantum mechanical calculations to model transition states and identify protein scaffolds capable of stabilizing high-energy intermediates [27]. Theozymes, or theoretical enzymes, represent optimal arrangements of amino acid residues that stabilize the transition state of a reaction; these are positioned into compatible protein scaffolds using algorithms like RosettaMatch [32].

Metalloprotein design presents particular challenges and opportunities, as metal cofactors expand the catalytic repertoire beyond natural amino acid chemistry. Successful metalloprotein design requires precise geometric positioning of metal-coordinating residues while maintaining the overall protein stability [27]. For example, zinc-containing adenosine deaminase has been computationally redesigned to catalyze organophosphate hydrolysis with a catalytic efficiency (kcat/Km) of ~10⁴ M⁻¹s⁻¹, representing a >10⁷-fold increase in activity [27].

Figure 1: Computational Protein Design Workflow. The design process begins with quantum mechanical modeling of transition states, proceeds through scaffold identification and sequence optimization, and culminates in experimental validation with iterative refinement.

Experimental Validation and Characterization

Expression and Purification Protocols

Designed proteins must be experimentally validated to confirm computational predictions. The first step involves gene synthesis and recombinant expression, typically in E. coli systems. Standard protocols include:

Gene Synthesis and Cloning: Codon-optimized genes are synthesized and cloned into expression vectors (e.g., pET series) with appropriate affinity tags (6xHis, GST, etc.) for purification.

Recombinant Expression: Transformed E. coli strains (BL21(DE3) or related) are grown in LB medium at 37°C to OD600 ≈ 0.6-0.8, induced with 0.1-1.0 mM IPTG, and expressed typically for 16-20 hours at 18-25°C for proper folding [27].

Protein Purification: Cell lysates are prepared by sonication or homogenization, and proteins are purified using immobilized metal affinity chromatography (IMAC) for His-tagged proteins, followed by size-exclusion chromatography to isolate monodisperse species [33].

Structural and Functional Characterization Methods

Table 2: Experimental Validation Methods for Designed Proteins

| Characterization Method | Information Obtained | Protocol Details | Interpretation Guidelines |

|---|---|---|---|

| Circular Dichroism (CD) Spectroscopy | Secondary structure content, thermal stability | Far-UV scans (190-260 nm); thermal ramps (20-95°C) | α-helical content: double minima at 208/222 nm; β-sheet: single minimum at 215 nm; Tm = melting temperature [27] |

| Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) | Binding affinity, kinetics | Immobilize one binding partner; flow analyte at varying concentrations | KD = koff/kon; 1:1 binding model; significance: KD < 100 nM generally considered high affinity [33] |

| Size Exclusion Chromatography with Multi-Angle Light Scattering (SEC-MALS) | Oligomeric state, molecular weight | Separation by hydrodynamic radius with inline light scattering | Monodispersity indicated by symmetric peak; molecular weight from light scattering independent of shape [33] |

| X-ray Crystallography | Atomic-level structure | Crystal growth, data collection, structure solution | RMSD < 1.0 Å between design model and experimental structure indicates high accuracy [33] |

| Enzyme Kinetics | Catalytic efficiency, substrate specificity | Varied substrate concentrations; measure initial velocities | kcat (turnover number); KM (Michaelis constant); kcat/KM (catalytic efficiency) [27] |

The Design Cycle: Iterative Refinement

The rational protein design process follows an iterative design cycle where computational predictions inform experimental constructs, and experimental results feed back to refine computational models [30]. This cycle continues until designs achieve target specifications. For example, in the computational design of organophosphate hydrolase activity, only four simultaneous mutations were required to convert mouse adenosine deaminase into an organophosphate hydrolase with a catalytic efficiency of ~10⁴ M⁻¹s⁻¹ [27].

Failed designs provide particularly valuable information for refining energy functions and search algorithms. Common failure modes include protein aggregation, incorrect folding, lack of expression, and absence of desired function. These outcomes indicate gaps in our understanding of protein folding principles or limitations in the energy functions used for design [30].

Advanced Applications and Case Studies

Enzyme Design for Novel Catalytic Functions

Computational enzyme design has progressed from creating catalysts for reactions with natural counterparts to engineering entirely novel activities not found in nature. Key successes include:

Kemp Eliminases: The design of enzymes that catalyze the Kemp elimination reaction, a model reaction for proton transfer from carbon, demonstrated the feasibility of creating novel biocatalysts. Using Rosetta-based algorithms, researchers designed enzymes with rate accelerations of >10⁵ over the uncatalyzed reaction [27] [32].

Retro-Aldolases: The design of enzymes that catalyze carbon-carbon bond cleavage in a retro-aldol reaction represented a more complex challenge requiring precise positioning of multiple catalytic residues. The successful designs achieved significant rate enhancements and demonstrated stereoselectivity [27].

Metalloenzyme Engineering: The introduction of metal binding sites into proteins has expanded the repertoire of catalyzed reactions. For example, the redesign of zinc-containing adenosine deaminase to hydrolyze organophosphates demonstrated the potential for engineering detoxification enzymes [27].

Therapeutic Protein Design

Rational design has produced significant advances in therapeutic protein engineering:

Chemically-Controlled Protein Switches: Computational design has created protein switches that respond to small molecules, enabling precise control of therapeutic activities. These include chemically disruptable heterodimers (CDHs) based on protein-protein interactions inhibited by clinical drugs such as Venetoclax [33]. These switches allow external control of therapeutic proteins, including CAR-T cells, using FDA-approved drugs.

Designed Immunogens: Structure-based design has created immunogens that focus immune responses on conserved epitopes of rapidly evolving pathogens. For HIV, computationally designed probes like RSC3 have enabled isolation of broadly neutralizing antibodies from patient sera [31] [34]. Nanoparticle display of designed immunogens has been used to elicit broadly protective responses against influenza and other viruses [34].

Design of Extreme Stability Proteins

Recent advances have enabled the design of proteins with exceptional stability properties. Using computational frameworks combining AI-guided structure prediction with molecular dynamics simulations, researchers have designed β-sheet proteins with maximized hydrogen bonding networks that exhibit remarkable mechanical stability [35]. These designed proteins demonstrated unfolding forces exceeding 1,000 pN (approximately 400% stronger than natural titin immunoglobulin domains) and retained structural integrity after exposure to 150°C [35].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Rational Protein Design

| Tool/Reagent | Type | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| ROSETTA Software Suite | Computational platform | Protein structure prediction, design, and docking | De novo enzyme design, protein-protein interface design, stability optimization [27] [31] |

| RosettaMatch | Algorithm | Scaffold identification for theozyme placement | Identifies protein scaffolds compatible with transition state geometry [32] |

| DEZYMER/ORBIT | Algorithm | Fixed-backbone design and rigid body docking | Active site grafting between unrelated protein folds [27] |

| CAVER | Software plugin | Identification and analysis of tunnels and channels | Engineering substrate access tunnels to alter enzyme specificity [32] |

| YASARA | Molecular modeling | Visualization, homology modeling, molecular docking | Structure analysis, mutant prediction, and docking experiments [32] |

| FRESCO | Computational framework | Enzyme stabilization through computational library design | Thermostabilization of enzymes for industrial applications [32] |

| SpyTag-SpyCatcher | Protein conjugation system | Covalent linkage of protein domains through isopeptide bond formation | Antigen display on nanoparticle vaccines [34] |

Figure 2: Integration of Rational Design with Central Dogma. Rational protein design reverses the traditional central dogma flow, starting from desired structure/function and working backward to identify sequences that will achieve target properties.

Rational protein design has matured from a theoretical concept to a practical discipline that continues to expand its capabilities. Emerging methodologies include the integration of machine learning approaches with physical modeling, as demonstrated by the prediction of microbial rhodopsin absorption wavelengths using group-wise sparse learning algorithms [36]. These data-driven approaches complement first-principles physical modeling and enable the identification of non-obvious sequence-structure-function relationships.

The continued development of protein design methodologies promises to address increasingly complex challenges in biotechnology and medicine. Future applications may include the design of molecular machines, programmable biomaterials, and dynamically regulated therapeutic systems. As computational power increases and algorithms become more sophisticated, the scope of designable proteins will continue to expand, enabling solutions to challenges in energy, medicine, and materials science that are currently inaccessible through natural proteins alone.