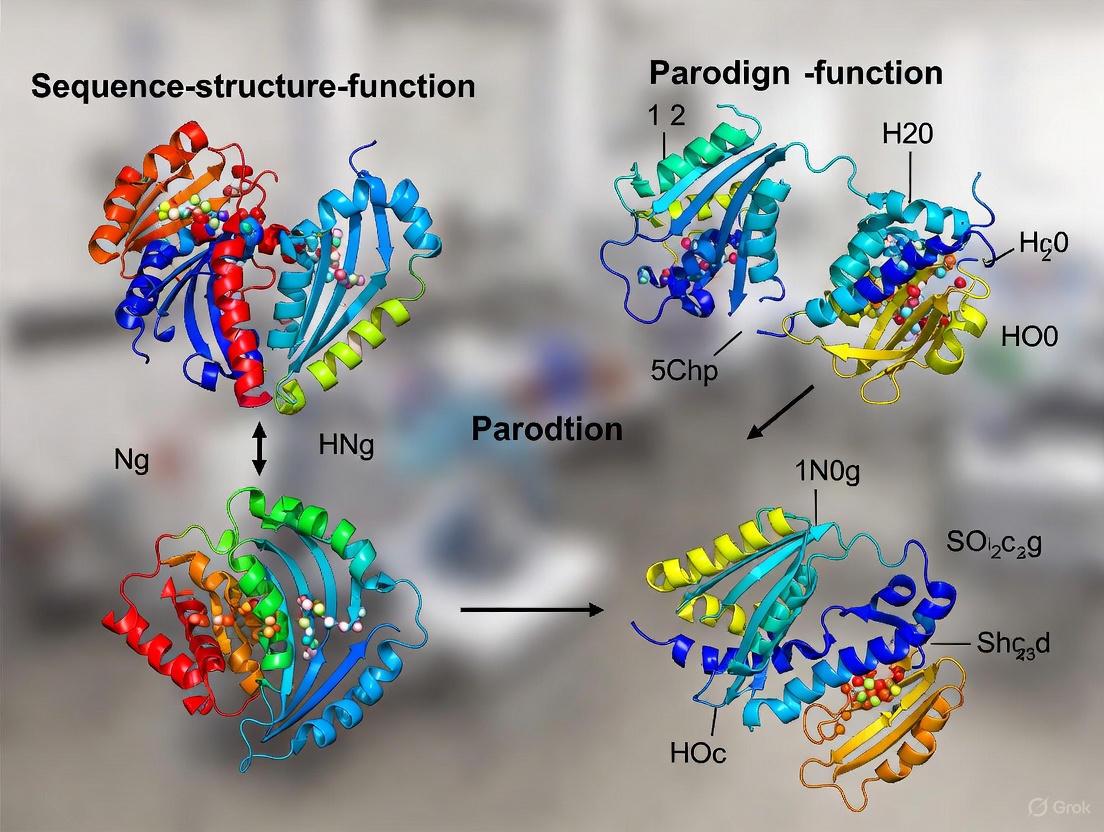

From Sequence to Therapy: Decoding Protein Structure-Function Relationships for Advanced Research and Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the protein sequence-structure-function relationship, a cornerstone of molecular biology with critical implications for biomedical research and therapeutic discovery.

From Sequence to Therapy: Decoding Protein Structure-Function Relationships for Advanced Research and Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the protein sequence-structure-function relationship, a cornerstone of molecular biology with critical implications for biomedical research and therapeutic discovery. We begin by exploring the foundational paradigm and its nuances, including how divergent sequences can achieve similar functions and the quantitative thresholds governing functional annotation transfer. The piece then details cutting-edge methodological approaches, from AI-driven structure prediction with tools like AlphaFold and Rosetta to experimental sequencing via mass spectrometry and Edman degradation. A dedicated troubleshooting section addresses common pitfalls such as misannotation and model quality assessment, while a final comparative analysis validates prediction accuracy against experimental data. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this resource synthesizes current knowledge to guide the reliable prediction and application of protein function.

The Protein Paradigm: How Sequence Dictates Structure and Function

The Central Dogma of molecular biology represents the fundamental framework for understanding the flow of genetic information within biological systems. First articulated by Francis Crick in 1958, this principle delineates the sequential transfer of information from nucleic acids to proteins, establishing a foundational paradigm for modern molecular biology [1]. The dogma originally posited that once information transfers into protein, it cannot flow backward to nucleic acid, emphasizing the unidirectional nature of genetic information transfer in biological systems [1]. In its contemporary understanding, the Central Dogma encompasses the core sequence of DNA replication, transcription of DNA to RNA, and translation of RNA into protein, representing the primary information transfer pathway that enables the conversion of genetic blueprints into functional molecular machines.

This whitepaper examines the Central Dogma through the lens of modern protein science, focusing particularly on how the linear amino acid sequence specified by genetic information determines the three-dimensional structure and ultimately the function of proteins. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding this sequence-structure-function relationship is paramount for rational drug design, understanding disease mechanisms, and engineering novel proteins. Recent advances in artificial intelligence and machine learning, particularly deep learning systems like AlphaFold, have revolutionized our ability to predict protein structure from sequence alone, creating unprecedented opportunities for accelerating research and therapeutic development [2] [3].

Theoretical Foundation: From Sequence to Structure

The Central Dogma: Detailed Molecular Processes

The Central Dogma encompasses several specific molecular processes that enable the faithful transfer of genetic information:

DNA Replication: A complex group of proteins called the replisome performs the replication of information from the parent DNA strand to the complementary daughter strand, ensuring genetic continuity across cell divisions [1].

Transcription: This process involves the transfer of information from DNA to messenger RNA (mRNA), facilitated by enzymes including RNA polymerase and transcription factors. In eukaryotic cells, the initial transcript (pre-mRNA) undergoes processing including 5' capping, polyadenylation, and splicing to produce mature mRNA [1].

Translation: The mature mRNA is translated into protein by ribosomes that read triplet codons, typically beginning with an AUG initiator methionine codon. Transfer RNAs (tRNAs) bearing specific amino acids match their anticodons to mRNA codons, adding amino acids to the growing polypeptide chain in the sequence specified by the genetic code [1].

The resulting polypeptide chain represents the primary structure of the protein—a linear sequence of amino acids whose properties ultimately determine the protein's final three-dimensional conformation and function. The protein folding process occurs as the chain emerges from the ribosome, often requiring chaperone proteins to ensure proper folding, and may be followed by additional post-translational modifications that fine-tune protein function [1].

Additional Information Transfer Pathways

Beyond the canonical pathway, several non-canonical information transfers expand the scope of the Central Dogma:

Reverse Transcription: The transfer of information from RNA to DNA, employed by retroviruses like HIV and eukaryotic retrotransposons, using enzymes called reverse transcriptases [1].

RNA Replication: The direct copying of RNA to RNA, utilized by many viruses through RNA-dependent RNA polymerases, which are also found in eukaryotes where they participate in RNA silencing mechanisms [1].

These additional pathways demonstrate that while the core principle of information flow from nucleic acids to proteins remains inviolate, nature has evolved diverse mechanisms for managing genetic information that expand beyond the simplest DNA→RNA→protein pathway.

Modern Research Frameworks: Sequence-Structure-Function Relationships

The Complexity of Genetic Architecture

A fundamental question in protein science concerns the complexity of the rules governing how a protein's amino acid sequence determines its structure and function. The relationship between sequence and function can be conceptualized in terms of epistatic interactions—the dependence of mutation effects on genetic context. If all residues acted independently, predicting function from sequence would be straightforward. However, high-order epistasis would make predictions idiosyncratic and context-dependent, requiring exhaustive characterization of all possible sequences [4].

Recent research suggests that sequence-function relationships are surprisingly simple and predictable. A 2024 study in Nature Communications presented a reference-free analysis method that jointly infers specific epistatic interactions and global nonlinearities using a comprehensive view of sequence space [4]. This approach demonstrates that context-independent amino acid effects and pairwise interactions, combined with a simple nonlinearity to account for limited dynamic range, explain a median of 96% of phenotypic variance across 20 experimental datasets, with over 92% in every case [4]. This indicates that only a tiny fraction of genotypes are strongly affected by higher-order epistasis, and sequence-function relationships are remarkably sparse, with a miniscule fraction of amino acids and interactions accounting for the majority of phenotypic variance [4].

Quantitative Structure-Property Relationship (QSPR) Frameworks

Quantitative Structure-Property Relationship (QSPR) theory provides a mathematical foundation for understanding sequence-structure-function relationships, based on the assumption that physicochemical properties are directly determined by molecular structure [5]. QSPR models utilize statistical approaches including multiple linear regression, Bayesian classification, and machine learning to correlate structural descriptors with functional properties [5].

These models have been successfully applied to predict various protein properties, including:

- Aqueous solubility using simple structural and physicochemical properties like lipophilicity (clogP) and molecular weight [5]

- Retention index in HPLC using interaction group descriptors that combine atomic E-state descriptors [5]

- Biological activity and membrane permeability using artificial neural networks that outperform traditional partial least squares analyses [5]

Advanced computational methods including COSMO-RS (Conductor-like Screening Model for Real Solvents), Hansen Solubility Parameters, and Perturbed Chain-Statistical Associating Fluid Theory (PC-SAFT) further enable researchers to correlate molecular structures with solvent properties and phase behavior, facilitating the customization of solvents for specific applications [5].

Methodological Advances: Protein Structure Prediction

The AlphaFold Revolution

A transformative development in protein science came with the introduction of AlphaFold, an AI system developed by Google DeepMind that predicts a protein's 3D structure from its amino acid sequence with accuracy competitive with experimental methods [2]. The 2020 release of AlphaFold2 represented a quantum leap in prediction quality, generating models that in some cases were indistinguishable from experimental maps [3]. The subsequent public release of the AlphaFold database, hosted by EMBL-EBI, has provided open access to over 200 million protein structure predictions, covering nearly all catalogued protein sequences and revolutionizing structural biology [2] [3].

The impact of AlphaFold on research has been profound, with nearly 40,000 journal articles citing the original AlphaFold2 paper as of 2025 [3]. Analysis shows that researchers using AlphaFold submitted approximately 50% more protein structures to the Protein Data Bank compared to non-users, significantly accelerating the pace of structural discovery [3]. The database has seen global adoption, with 3.3 million users across 190 countries, including over one million from low- and middle-income nations, democratizing access to structural information [3].

Addressing the Currency Challenge: AlphaSync

A significant limitation in static protein structure databases is the inability to incorporate new sequence information as it becomes available. To address this challenge, scientists at St. Jude Children's Research Hospital developed AlphaSync, a continuously updated database that ensures researchers work with the most current structural information [6].

AlphaSync maintains 2.6 million predicted protein structures across hundreds of species, updating predictions when new or modified sequences become available in UniProt, the largest protein sequence database [6]. When first implemented, this system identified a backlog of 60,000 outdated structures, including 3% of human proteins, highlighting the critical importance of currency in structural databases [6]. Beyond mere structure prediction, AlphaSync provides pre-computed data including residue interaction networks, surface accessibility, and disorder status, and presents 3D structural information in simplified 2D tabular formats that are more accessible for researchers and more amenable to machine learning applications [6].

Table 1: Comparison of Major Protein Structure Prediction Resources

| Resource | Developer | Structures | Update Frequency | Special Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AlphaFold DB | Google DeepMind & EMBL-EBI | ~240 million | Static releases | Broad coverage, established resource, integrates with UniProt [2] |

| AlphaSync | St. Jude Children's Research Hospital | 2.6 million | Continuous | Updated structures, residue interaction networks, surface accessibility, disorder status [6] |

| AlphaFold2 Code | Google DeepMind | User-dependent | Open source | Enables custom predictions, including multimer predictions [2] |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Reference-Free Analysis of Genetic Architecture

Reference-free analysis (RFA) represents a methodological advance for dissecting sequence-function relationships without the biases introduced by reference-based approaches that designate a single wild-type sequence [4]. The RFA protocol involves:

Data Collection: Measure phenotypes for a diverse set of protein variants, ensuring broad sampling of sequence space.

Global Mean Calculation: Compute the mean phenotype across all measured sequences as the zero-order term.

First-Order Effects: Calculate the context-independent effect of each amino acid state as the difference between the mean phenotype of all sequences containing that state and the global mean.

Epistatic Effects: Determine pairwise and higher-order interaction effects as the difference between the mean phenotype of sequences containing the combination and that expected given lower-order effects.

Model Estimation: Use least-squares regression to estimate model terms, which remains accurate even with 50% missing data due to the averaging across sequence space.

This approach explains the maximum possible amount of phenotypic variance for any linear model of a given order, with greater robustness to measurement noise compared to reference-based methods [4].

Integrated Workflow for Structure-Function Analysis

The following workflow integrates modern computational and experimental approaches for comprehensive structure-function analysis:

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Protein Structure-Function Studies

| Resource | Function/Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|

| AlphaFold Database | Protein structure prediction | >240 million structures, covers most known proteins, freely accessible [2] [3] |

| AlphaSync Database | Updated protein structures | Continuous updates, residue interaction networks, surface accessibility [6] |

| UniProt | Protein sequence database | Largest protein sequence repository, source for updates [6] |

| Reference-Free Analysis (RFA) | Sequence-function modeling | Robust to noise, handles missing data, explains >92% variance [4] |

| QSPR Models | Property prediction | Predicts solubility, retention, activity from structural descriptors [5] |

| Cryo-EM & X-ray Crystallography | Experimental structure validation | Gold-standard methods for determining atomic-level structures [3] |

Quantitative Findings in Sequence-Function Relationships

Recent research has yielded substantial quantitative insights into the nature of sequence-function relationships in proteins:

Table 3: Quantitative Findings on Sequence-Function Relationships

| Parameter | Finding | Implication |

|---|---|---|

| Variance Explained | >92% of phenotypic variance explained by zero, first, and second-order effects [4] | High predictability of sequence-function relationships |

| Higher-Order Epistasis | Only a tiny fraction of genotypes strongly affected by higher-order epistasis [4] | Genetic architecture is fundamentally simple and tractable |

| Data Efficiency | RFA models accurately estimated with 50% missing data [4] | Robust to incomplete sampling of sequence space |

| Structural Coverage | >240 million structures in AlphaFold DB [3] | Nearly comprehensive coverage of known proteins |

| Research Impact | ~40,000 journal articles citing AlphaFold2 [3] | Widespread adoption across biological sciences |

| Update Requirement | 3% of human proteins had outdated structures before AlphaSync [6] | Critical need for continuous database updating |

The Central Dogma continues to provide a robust conceptual framework for understanding how genetic information flows from DNA sequence to functional protein machines. Contemporary research has revealed that the relationship between amino acid sequence and protein function is remarkably deterministic and predictable, with context-independent amino acid effects and pairwise interactions explaining the vast majority of functional variance [4]. The development of powerful AI-based structure prediction tools like AlphaFold has democratized access to protein structural information, while methodological advances like reference-free analysis provide more robust frameworks for interpreting sequence-function relationships [2] [4].

For researchers and drug development professionals, these advances create unprecedented opportunities to connect genetic variation to protein function, understand disease mechanisms at atomic resolution, and accelerate the design of novel therapeutics. The integration of continuously updated structural databases like AlphaSync with sophisticated analytical frameworks promises to further enhance our ability to traverse the path from amino acid sequence to three-dimensional functional machine, fulfilling the promise of the Central Dogma as a guiding principle for 21st century molecular biology and medicine.

This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical guide to the four hierarchical levels of protein organization, framed within the broader thesis that a protein's amino acid sequence intrinsically dictates its three-dimensional structure, which in turn governs its biological function. Understanding this sequence-structure-function relationship is paramount for advancements in structural biology, disease mechanism elucidation, and rational drug design. We detail the biochemical principles defining each structural level, present experimental and computational methodologies for their determination, and summarize key quantitative data for comparative analysis. The document is intended to serve as a resource for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals engaged in protein science.

Proteins are fundamental macromolecules responsible for a vast array of biological functions, including catalysis, structural support, transport, and signaling [7] [8]. The functions of these complex biomolecules are exclusively determined by their intricate three-dimensional structures [7]. The organization of proteins is conceptually divided into four hierarchical levels: primary, secondary, tertiary, and quaternary structures [9]. This framework is essential for systematically understanding how a linear amino acid sequence folds into a functional, often globular, form. Anfinsen's dogma established that all the information required for a protein to attain its native, biologically active conformation is encoded in its primary sequence [7]. However, the Levinthal paradox highlights the profound complexity of this process, noting that proteins cannot randomly sample all possible conformations but must follow defined folding pathways [7]. The exponential growth of protein sequence data, with over 200 million entries in TrEMBL compared to only about 200,000 known structures in the Protein Data Bank (PDB), has created a critical gap, necessitating robust methods for predicting structure from sequence [7]. This review delves into the defining characteristics of each structural level and the experimental and computational techniques used to decipher them, underscoring their collective importance in modern biological and pharmaceutical research.

Primary Structure

Definition and Composition

The primary structure of a protein is defined as the linear sequence of amino acids in its polypeptide chain [10] [8] [11]. By convention, this sequence is reported and read from the amino-terminal (N) end to the carboxyl-terminal (C) end [10] [12]. Each amino acid is connected to the next by a peptide bond, a covalent linkage formed between the carboxyl group of one amino acid and the amino group of another, releasing a water molecule in a dehydration condensation reaction [7] [11]. This sequence is genetically determined by the nucleotide sequence of the corresponding gene [7] [9].

Notation and Representation

Protein primary structure can be represented using a string of letters, employing either a three-letter code or a single-letter code for the 20 naturally encoded amino acids [10]. Special notation is used to represent ambiguous or general amino acid types, which is particularly useful in sequence alignments and profile analysis. Key symbols are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1: Standard and Ambiguous Amino Acid Notation in Primary Sequences

| Symbol | Description | Residues Represented |

|---|---|---|

| B | Aspartate or Asparagine | D, N |

| Z | Glutamate or Glutamine | E, Q |

| J | Leucine or Isoleucine | I, L |

| X | Any amino acid or unknown | All |

| Φ | Hydrophobic | V, I, L, F, W, M |

| ζ | Hydrophilic | S, T, H, N, Q, E, D, K, R, Y |

| + | Positively Charged | K, R, H |

| - | Negatively Charged | D, E |

Modifications and Cleavage

The initial polypeptide chain often undergoes significant post-translational modifications (PTMs) that are considered part of its primary structure specification [10]. These include:

- Disulfide bond formation: Covalent cross-links between the thiol groups of cysteine residues, which stabilize the protein's structure [10].

- N-terminal modifications: Including acetylation, formylation, and the formation of pyroglutamate, which can neutralize charge or block the terminus [10].

- Side-chain modifications: A diverse set of chemical alterations including phosphorylation of serine, threonine, or tyrosine; glycosylation of serine, threonine, or asparagine; methylation of lysine and arginine; and hydroxylation of proline and lysine [10].

Furthermore, many proteins are synthesized as inactive precursors that are activated by proteolytic cleavage, where specific peptide bonds are cleaved to remove inhibitory segments or pro-peptides [10].

Functional Consequences of Alterations

The primary structure is the foundational determinant of a protein's final shape and function. A single amino acid substitution can have dramatic pathological consequences. A canonical example is sickle cell anemia, where a mutation in the β-globin subunit of hemoglobin causes a substitution of valine for glutamic acid at the sixth position (E6V) [8] [9]. This single change alters the protein's solubility and leads to the polymerization of hemoglobin under low oxygen tension, distorting red blood cells into a sickle shape and causing vascular occlusions [9].

Secondary Structure

Definition and Fundamental Elements

Secondary structure refers to the local spatial conformation of the polypeptide backbone, excluding the side chains, stabilized primarily by hydrogen bonds between backbone carbonyl oxygen and amide hydrogen atoms [13] [8]. The two most common and stable secondary structures are the alpha-helix (α-helix) and the beta-sheet (β-sheet), while beta-turns and loops connect these regular elements [13].

Table 2: Geometrical Parameters of Protein Helices

| Geometry Attribute | α-helix | 310 helix | π-helix |

|---|---|---|---|

| Residues per turn | 3.6 | 3.0 | 4.4 |

| Translation per residue | 1.5 Å | 2.0 Å | 1.1 Å |

| Radius of helix | 2.3 Å | 1.9 Å | 2.8 Å |

| Pitch | 5.4 Å | 6.0 Å | 4.8 Å |

Alpha-Helix

The alpha-helix is a right-handed helical coil stabilized by hydrogen bonds that form between the carbonyl oxygen of residue i and the amide hydrogen of residue i+4, making it a very stable structure [13] [12]. Key properties include:

- It completes one turn every 3.6 residues [12].

- It has a pitch (rise per turn) of approximately 5.4 Å [12].

- The backbone dihedral angles (φ, ψ) for residues in an α-helix are typically in the range of -60° and -50°, placing them in the lower left quadrant of the Ramachandran plot [12].

- The structure has an overall macroscopic dipole moment due to the alignment of individual peptide bond dipoles, with a positive partial charge at the N-terminus and a negative partial charge at the C-terminus [12].

- Amino acids exhibit different propensities for forming α-helices. Ala, Glu, Leu, and Lys ("MALEK") are strong helix-formers, while Proline acts as a "helix-breaker" due to its rigid cyclic structure, which introduces a kink and cannot form the required hydrogen bond [13] [12].

Beta-Sheet

The beta-sheet (or beta-pleated sheet) is an extended, sheet-like structure formed by multiple stretches of the polypeptide chain, known as beta-strands [12] [8]. Hydrogen bonds form between the backbone atoms of adjacent strands, stabilizing the sheet. The side chains of adjacent amino acids protrude from the zig-zagging backbone in alternating directions [9]. Beta-sheets are classified based on the relative direction of their constituent strands:

- Antiparallel β-sheet: Neighboring strands run in opposite directions (N→C adjacent to C→N). The hydrogen bonds in this configuration are nearly perpendicular to the strands [12].

- Parallel β-sheet: Neighboring strands run in the same direction. The hydrogen bonds are slanted and generally longer and weaker than in antiparallel sheets [12].

- Mixed β-sheet: A combination of parallel and antiparallel hydrogen bonding within a single sheet, which is common in globular proteins [12].

A beta-barrel is a special type of beta-sheet structure where antiparallel strands twist and coil to form a closed, barrel-like structure, often found in transmembrane proteins like aquaporins [8].

Experimental Determination and Prediction

The secondary structure content of a protein is routinely estimated using spectroscopic techniques. Far-ultraviolet circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy is a primary method, where a double minimum at 208 nm and 222 nm indicates α-helical structure, while a single minimum at 217 nm is characteristic of β-sheet structure [13]. Infrared spectroscopy can also detect differences in amide bond oscillations due to hydrogen-bonding patterns [13].

Formal assignment of secondary structure from atomic coordinates (e.g., from X-ray crystallography or NMR) is performed using algorithms like DSSP (Dictionary of Protein Secondary Structure), which classifies structure based on hydrogen-bonding patterns [13]. DSSP uses eight assignment codes (e.g., H for α-helix, E for extended strand, B for isolated β-bridge, etc.) [13].

Early methods for predicting secondary structure from amino acid sequence alone, such as the Chou-Fasman and GOR methods, achieved limited accuracy [13]. Modern methods, including PSIPRED and PORTER, leverage multiple sequence alignments and machine learning (e.g., neural networks) to identify evolutionary patterns, pushing accuracies to nearly 80% [13].

Figure 1: Workflow for modern deep learning-based protein secondary structure prediction.

Tertiary Structure

Definition and Stabilizing Forces

The tertiary structure is the overall three-dimensional shape of an entire polypeptide chain, formed by the folding and packing of secondary structure elements and the arrangement of side chains [7] [9]. This structure results from interactions between distant side chains (R groups) along the sequence, which stabilize the native, functional conformation of the protein [8]. The native state of a globular protein represents a thermodynamically stable energy minimum under physiological conditions [7]. Key stabilizing interactions include:

- Hydrophobic interactions: The burial of nonpolar side chains away from the aqueous environment is a major driving force in protein folding.

- Hydrogen bonding: Between polar side chains and with the solvent.

- Electrostatic interactions: Including salt bridges between positively and negatively charged side chains.

- Van der Waals forces: Between closely packed atoms in the protein core.

- Disulfide bonds: Covalent cross-links that can lock the folded structure in place.

Structural Classes

Globular proteins can be categorized into structural classes based on the composition and arrangement of their secondary structure elements [7]:

- All-α proteins: Domains are composed predominantly of alpha-helices.

- All-β proteins: Domains are composed predominantly of beta-sheets.

- α/β proteins: Contain beta-sheets surrounded by alpha-helices.

- α+β proteins: Contain segregated regions of alpha-helices and beta-sheets.

Quaternary Structure

Definition and Biological Significance

Quaternary structure is the highest level of protein organization and refers to the three-dimensional arrangement of multiple folded polypeptide chains, known as subunits, into a multisubunit complex [14]. Not all proteins possess quaternary structure; it is a property of multimeric proteins. The subunits can be identical (homomeric) or different (heteromeric) [14]. This level of organization is crucial for many biological functions, including:

- Cooperativity: As exemplified by hemoglobin, where the binding of oxygen to one subunit increases the affinity of the remaining subunits [14].

- Allostery: The regulation of a protein's activity through the binding of an effector molecule at a site distinct from the active site [14].

- Formation of complex molecular machines: Such as ribosomes, proteasomes, and viral capsids [14].

Nomenclature and Symmetry

The nomenclature for protein quaternary structure is based on the number of subunits, using names that end in -mer [14].

- 2 = dimer

- 3 = trimer

- 4 = tetramer

- 5 = pentamer

- 6 = hexamer

These complexes often display symmetry. For example, a tetramer may have cyclic symmetry (C4) or dihedral symmetry (D2), with the latter often described as a "dimer of dimers" [14]. Viral capsids represent extreme examples of quaternary structure, often composed of hundreds of protein subunits arranged with high symmetry [14].

Experimental Determination

Determining quaternary structure requires techniques that analyze the native, intact complex under non-denaturing conditions [14].

- Analytical Ultracentrifugation: Measures the sedimentation velocity of a complex to determine its molecular mass and shape in solution.

- Surface-Induced Dissociation Mass Spectrometry: A powerful technique for characterizing the stoichiometry and arrangement of subunits within a complex [14].

- Dynamic Light Scattering: Measures the hydrodynamic radius of a complex, providing information about its size.

- NMR Spectroscopy: Can be used to study protein-protein interactions and the structure of smaller complexes in solution [14].

It is critical to note that techniques like SDS-PAGE, which use denaturing conditions, typically dissociate non-covalent complexes and are not suitable for determining native quaternary structure [14].

Figure 2: A multi-technique experimental workflow for determining protein quaternary structure.

Experimental and Computational Methodologies

Experimental Structure Determination

Experimental determination of protein structure is a cornerstone of structural biology. The primary high-resolution methods are:

- X-ray Crystallography: The gold standard for determining atomic-resolution structures, requiring the protein to be crystallized. It provides a static snapshot of the protein's structure [7].

- Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) Spectroscopy: Allows for the determination of protein structure in solution, providing insights into protein dynamics and flexibility. It is particularly suited for smaller proteins [7].

- Cryo-Electron Microscopy (cryo-EM): Involves flash-freezing protein samples and imaging them with an electron microscope. It is exceptionally powerful for determining the structures of large complexes, such as those with quaternary structure, and membrane proteins that are difficult to crystallize [7].

Computational Structure Prediction

Computational methods have emerged to bridge the gap between the number of known sequences and experimentally solved structures. These are broadly categorized as follows [7]:

- Template-Based Modeling (TBM): Relies on identifying a known protein structure (a template) that is homologous to the target sequence. This category includes homology modeling (for high sequence similarity) and threading or fold recognition (for low sequence similarity but similar folds) [7].

- Template-Free Modeling (TFM): Predicts structure directly from sequence, often using deep learning and co-evolutionary information from multiple sequence alignments (MSAs). Modern AI-based tools like AlphaFold2 and RoseTTAFold fall into this category and have achieved remarkable accuracy [7].

- Ab initio Modeling: Based purely on physicochemical principles and force fields, without relying on known structural templates. This approach seeks to simulate the protein folding process from an unfolded state [7].

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Protein Structure Analysis

| Reagent / Tool | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| Protein Crystallization Kits | Contains sparse matrix conditions to screen for optimal crystal growth for X-ray crystallography. |

| Isotopically Labeled Amino Acids (¹⁵N, ¹³C) | Essential for multi-dimensional NMR spectroscopy to assign resonances and determine 3D structure. |

| Cross-linking Reagents (e.g., BS3, DSS) | Chemically cross-link proximal subunits in a complex for MS or SDS-PAGE analysis of quaternary structure. |

| Size Exclusion Chromatography (SEC) Columns | Separate proteins and complexes based on hydrodynamic size; used for purification and analysis of oligomeric state. |

| Monoclonal Antibodies | Used in co-immunoprecipitation (co-IP) to identify and isolate protein-protein interaction partners. |

| Fluorescent Dyes (for FRET) | Label proteins to study interactions and conformational changes via Förster Resonance Energy Transfer. |

Clinical Significance and the Sequence-Structure-Function Relationship

The direct link between protein sequence, structure, and function is starkly illustrated in human disease. Pathologies often arise from mutations that disrupt the normal folding pathway or the stability of the native state.

- Sickle Cell Anemia: As previously described, a single E6V mutation in the primary structure of β-globin destabilizes the tertiary and quaternary structure of hemoglobin, leading to polymerization and disease [8] [9].

- Prion Diseases: Including Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease and bovine spongiform encephalopathy, these involve the conversion of the normal cellular prion protein (PrPC), which is rich in α-helix, into a pathological form (PrPSc) that is rich in β-sheet [8]. This change in secondary structure leads to the formation of insoluble, non-degradable aggregates that damage neural tissue [8].

- Amyloidosis: A class of diseases where proteins misfold into β-sheet-rich aggregates known as amyloid fibrils. This can be systemic, as in primary amyloidosis involving immunoglobulin light chains, or localized, as in Alzheimer's disease, where the β-amyloid peptide aggregates into plaques in the brain [8].

These examples underscore that the primary sequence must not only code for a functional tertiary structure but must also avoid alternative, pathological folding pathways. This understanding is the bedrock of therapeutic strategies aimed at stabilizing native protein structures or inhibiting aberrant protein aggregation.

The four hierarchical levels of protein organization—primary, secondary, tertiary, and quaternary—provide a fundamental framework for deconstructing and understanding the intricate architecture of proteins. The central dogma of structural biology, that sequence dictates structure and structure dictates function, remains a powerful guiding principle. Disruptions at any level of this hierarchy can lead to a loss of function or a gain of toxic function, resulting in disease. The field is currently being transformed by the integration of high-resolution experimental methods with powerful computational predictions, as exemplified by deep learning models like AlphaFold. For researchers and drug development professionals, a deep understanding of these structural principles is indispensable for rationally designing experiments, interpreting pathological mechanisms, and developing novel therapeutics that target specific proteins or their interactions. The continued synthesis of experimental and computational approaches will be crucial for unraveling the remaining complexities of the protein universe.

The central dogma of molecular biology has long been governed by the sequence-structure-function paradigm, which posits that similar protein sequences fold into similar structures that perform similar functions. However, recent advances in structural biology and deep learning have revealed fundamental limitations in this classical framework. This technical review synthesizes evidence from large-scale structural studies demonstrating that similar biological functions can indeed emerge from divergent sequences and structural scaffolds. We examine the mechanistic basis for this phenomenon and present standardized experimental protocols for its investigation, alongside a curated toolkit of computational resources essential for researchers probing the complex landscape of protein function prediction. Our analysis underscores the need for a paradigm shift from sequence-centric to structure-aware function annotation across all branches of biological research and therapeutic development.

For decades, structural biology has operated under the foundational assumption that similar protein sequences give rise to similar structures and functions [15]. This principle has guided protein annotation efforts, drug discovery pipelines, and evolutionary studies. However, the exponential growth of available protein sequences, coupled with recent breakthroughs in structure prediction, has revealed substantial areas of the protein universe where this paradigm does not hold [15].

Historically, homology-based function prediction dominated computational approaches, wherein proteins were annotated based on sequence similarity to characterized proteins [16]. While this method remains valuable for closely related sequences, its limitations become apparent when sequence similarity drops below 30-40% identity, or when proteins evolve different functions despite high sequence similarity [16]. The classical view is further challenged by numerous examples where distinct structural folds perform remarkably similar biochemical functions, suggesting evolutionary convergence at the functional rather than structural level.

The advent of large-scale structure prediction initiatives, including citizen science projects and deep learning approaches like AlphaFold2, has dramatically expanded the known structure space [15]. Analysis of these structural datasets reveals a protein universe that is largely continuous and saturated, yet surprisingly flexible in its mapping of sequence and structure to function [15]. This technical review examines the evidence supporting this revised understanding of protein function emergence and provides practical methodologies for investigating these relationships in silico.

Quantitative Evidence from Large-Scale Studies

Recent large-scale structural studies have provided quantitative evidence challenging the classical sequence-structure-function paradigm. The table below summarizes key findings from major investigations that document functional similarity despite sequence and structural divergence.

Table 1: Evidence from Large-Scale Studies of Sequence-Structure-Function Relationships

| Study | Dataset Size | Key Finding | Methodology | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MIP Database [15] | ~200,000 microbial protein models | 148 novel folds identified; continuous structural space observed | Rosetta de novo modeling & DMPfold; DeepFRI functional annotation | Demonstrates structural continuity and functional conservation across distinct folds |

| DPFunc [17] | PDB structures + large-scale CAFA-style dataset | Outperforms homology-based methods (16-27% Fmax improvement) | Domain-guided deep learning with structure information | Shows domain context, not just sequence, determines function |

| Gal1/Gal3 Case [16] | Paralogs with 73% sequence identity | Divergent functions (galactokinase vs. transcriptional inducer) | Structural and functional characterization | Challenges assumption that high sequence similarity guarantees identical function |

| Enzyme Substrate Diversity [16] | Enzyme pairs with 50% sequence identity | 10% show different substrates; different reactions common | Comparative enzymology and sequence analysis | Reveals functional divergence even at moderate sequence identity |

Analysis of the microbial protein universe reveals a structural space that is continuous rather than discretely partitioned, with smooth transitions between folds suggesting functional promiscuity across distinct architectural contexts [15]. This structural continuity enables the emergence of similar functions from different structural scaffolds through evolutionary processes that optimize functional residues rather than overall fold conservation.

The limitations of traditional homology-based approaches are quantitatively demonstrated by the performance gap between methods like BLAST and modern structure-aware predictors. DPFunc, which incorporates domain-guided structure information, achieves improvements in Fmax of 16%, 27%, and 23% for molecular function, cellular component, and biological process predictions, respectively, compared to structure-based methods lacking domain context [17]. This performance gap highlights the importance of local structural environments over global sequence or structure similarity alone.

Mechanistic Basis for Functional Convergence

Local Structural Motifs vs. Global Fold

The primary mechanism enabling similar functions from different sequences and structures involves the conservation of local structural motifs responsible for functional activity, rather than conservation of the entire protein fold. Specific arrangements of catalytic residues, binding pockets, or interaction surfaces can be maintained across different structural scaffolds through convergent evolution or evolutionary tinkering.

Table 2: Mechanisms Enabling Functional Similarity from Divergent Sequences/Structures

| Mechanism | Description | Example | Experimental Detection |

|---|---|---|---|

| Active Site Convergence | Distinct folds evolve similar catalytic triads or binding surfaces | unrelated enzyme families evolving similar catalytic mechanisms | Computational solvent mapping [16]; motif identification |

| Domain Shuffling | Functional domains combine in novel architectural contexts | multi-domain proteins with new functions from existing parts | Domain analysis (e.g., InterProScan [17]) |

| Paralogous Divergence | Gene duplication followed by functional specialization | Gal1/Gal3 paralogs with different functions [16] | Phylogenetic analysis & functional assays |

| Structural Exaptation | Existing structural elements co-opted for new functions | sugar-binding sites evolving from non-binding scaffolds | Structural comparison & evolutionary tracing |

For enzymes, predictions of specific functions are especially challenging, as they only need a few key residues in their active site; hence very different sequences can have very similar activities [16]. This local functional conservation explains why global sequence similarity thresholds (e.g., 30-40% identity) often fail to accurately predict function, particularly for enzymes where even with sequence identity of 70% or greater, 10% of any pair of enzymes have different substrates [16].

The Role of Domain Context in Function Determination

Protein domains represent fundamental units of function, and their contextual arrangement within larger structural scaffolds significantly influences functional specificity. Modern deep learning approaches leverage this insight by explicitly incorporating domain guidance when predicting function from structure. DPFunc demonstrates that domain information contained in protein sequences provides valuable insights for protein function prediction that surpass what can be gleaned from overall structure alone [17].

The importance of domain context explains why traditional structure-based methods that average all amino acid features into protein-level representations often fail to detect functionally relevant regions. By scanning sequences for known domains and using this information to guide attention mechanisms, deep learning models can identify key residues or regions in protein structures that are closely related to their functions, even when these regions are embedded in different overall structural contexts [17].

Experimental Methodologies and Protocols

Large-Scale Structure-Function Annotation

The following workflow outlines the standardized protocol for large-scale structure prediction and functional annotation, as implemented in recent studies of the microbial protein universe:

Figure 1: Workflow for large-scale structure-function annotation. Key quality control steps ensure model reliability before functional annotation and novel fold identification.

Protocol Steps:

Input Sequence Curation: Select non-redundant protein sequences without matches to existing structural databases. Filter for sequences that produce multiple-sequence alignments with sufficient depth (N_eff > 16) for robust structure prediction [15].

Structure Prediction: Generate structural models using complementary approaches:

- Rosetta de novo modeling: Generate 20,000 models per sequence using citizen science computing resources (e.g., World Community Grid) [15].

- DMPfold: Generate up to 5 models per sequence using machine learning approaches [15].

- AlphaFold2: Use for verification of novel folds, though computational cost may limit large-scale application [15].

Model Quality Assessment: Apply multiple quality metrics to filter out low-quality models:

- Calculate Model Quality Assessment (MQA) score by averaging pairwise TM-scores of the 10 lowest-scoring Rosetta models; retain models with MQA score > 0.4 [15].

- Filter by coil content: Rosetta models with >60% coil content and DMPfold models with >80% coil content are typically low quality and should be removed [15].

- Assess agreement between Rosetta and DMPfold models; retain models with TM-score ≥ 0.5 between methods [15].

Functional Annotation: Annotate curated models using structure-based Graph Convolutional Network embeddings (e.g., DeepFRI) that provide residue-specific functional predictions [15].

Novel Fold Identification: Compare models against representative domains in CATH and PDB using TM-score cutoff of 0.5. Verify putative novel folds with independent structure prediction methods to eliminate false positives [15].

Domain-Guided Function Prediction

The following protocol details the DPFunc methodology for accurate function prediction using domain-guided structure information:

Figure 2: Domain-guided function prediction workflow. Domain information directs attention to functionally relevant regions within structures.

Protocol Steps:

Residue-Level Feature Learning:

- Generate initial residue features using pre-trained protein language models (ESM-1b) based on protein sequences [17].

- Construct contact maps from protein structures (experimental or predicted) based on 3D coordinates of amino acids [17].

- Process contact maps and residue features through Graph Convolutional Network (GCN) layers with residual connections to update and learn final residue-level features [17].

Domain Identification and Embedding:

- Scan protein sequences using InterProScan to identify functional domains by comparison to background databases [17].

- Convert identified domains into dense vector representations using embedding layers that capture their unique characteristics [17].

- Sum domain embeddings to create protein-level domain information [17].

Attention-Guided Feature Integration:

- Implement attention mechanism inspired by transformer architecture to interweave protein-level domain features and residue-level features [17].

- Calculate importance scores for each residue based on domain guidance [17].

- Generate protein-level features through weighted summation of residue-level features using attention-derived importance scores [17].

Function Prediction and Post-Processing:

- Combine protein-level features with initial residue-level features through fully connected layers to predict Gene Ontology terms across molecular function, cellular component, and biological process ontologies [17].

- Apply post-processing to ensure consistency with the hierarchical structure of GO terms, which significantly improves prediction performance [17].

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Investigating Sequence-Structure-Function Relationships

| Tool/Resource | Type | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| DPFunc [17] | Deep Learning Model | Protein function prediction with domain-guided structure information | State-of-the-art function prediction; identifying key functional residues |

| DeepFRI [15] | Graph Convolutional Network | Structure-based function prediction with residue-level annotation | Large-scale functional annotation of structural models |

| Structome-AlignViewer [18] | Visualization Tool | 3Di character alignment visualization alongside molecular structures | Assessing alignment quality for structure-based evolutionary analysis |

| InterProScan [17] | Domain Identification | Scans sequences against databases to detect protein domains | Essential for domain-guided approaches; identifying functional units |

| ESM-1b [17] | Protein Language Model | Generates residue-level features from sequences alone | Feature extraction for sequences without structural information |

| 3D-Beacons Network [19] | Structure Repository | Discovers experimental and predicted structures for sequences | Accessing structural data for proteins of interest |

| Jalview [19] | Alignment Visualization | Multiple sequence alignment editing, visualization, and analysis | Traditional sequence-based analysis and comparison |

The compelling evidence from large-scale structural studies necessitates a fundamental shift in how we conceptualize and investigate protein sequence-structure-function relationships. The classical view that similar sequences dictate similar structures and functions represents an oversimplification that fails to account for the remarkable functional plasticity observed across the protein universe. Rather than discrete mapping, we observe a continuous structural space where similar functions can emerge from different sequences and structural scaffolds through conservation of local functional motifs and domain contexts.

This revised understanding has profound implications for biomedical research and therapeutic development. Drug discovery efforts must move beyond sequence similarity alone when assessing potential off-target effects or repurposing opportunities, as functionally similar binding sites can occur in structurally distinct proteins. Functional annotation pipelines require integration of structure-aware, domain-guided prediction methods to accurately characterize the rapidly expanding universe of unannotated sequences.

Future research directions should prioritize the development of integrated databases that capture continuous structure-function relationships rather than discrete classifications. Methodological advances should focus on improving residue-level function prediction and elucidating the evolutionary mechanisms that enable functional convergence across distinct structural scaffolds. By embracing this more nuanced understanding of protein function emergence, researchers can accelerate discovery across basic biology, protein engineering, and therapeutic development.

The paradigm that similar protein sequences yield similar structures and functions has long guided structural biology. However, a more complex reality is emerging, where functional conservation can persist despite significant sequence divergence, challenging the establishment of universal sequence identity thresholds. This whitepaper synthesizes current research to quantify these relationships, presenting data on thresholds across different protein systems, detailing experimental protocols for functional validation, and providing a toolkit for researchers. Framed within the broader context of protein sequence-structure-function research, this guide underscores that while heuristic thresholds are valuable, functional conservation is often governed by contextual factors beyond mere sequence identity, including genomic context, structural motifs, and syntenic relationships.

The classical sequence-structure-function paradigm posits that a protein's amino acid sequence determines its three-dimensional structure, which in turn dictates its biological function. This framework implies that sequence similarity can be a reliable proxy for functional similarity. However, the exponential growth of genomic data and advances in structure prediction have revealed a more nuanced landscape. It is now evident that similar functions can be achieved by different sequences and even different structures, a phenomenon widespread in rapidly evolving systems like host-defense mechanisms [20] [15]. Conversely, minute sequence changes can sometimes lead to complete loss of function. This complexity necessitates a quantitative and evidence-based approach to define the relationship between sequence identity and functional conservation. Such an approach is critical for applications in protein engineering, functional annotation in genomics, and drug discovery, where accurately predicting function from sequence is paramount. This guide explores the quantitative thresholds, experimental methodologies, and conceptual frameworks needed to navigate this complex relationship.

Quantitative Data on Sequence Identity and Functional Conservation

The relationship between sequence identity and functional conservation is not uniform across all proteins. The thresholds can vary significantly depending on the protein family, the specific function being assessed, and the evolutionary pressures acting on the system. The following table synthesizes quantitative findings from recent studies, highlighting this variability.

Table 1: Experimentally Determined Sequence-Function Relationships Across Protein Systems

| Protein System | Sequence Identity to Natural Protein | Functional Outcome | Experimental Assay | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| De Novo Anti-CRISPR (Acr) [20] | No significant similarity | Robust activity | Phage defense assay | Generative AI can design functional proteins with no sequence homology to known naturals. |

| De Novo Toxin (EvoRelE1) [20] | 71% to known RelE toxin | Strong growth inhibition (∼70% reduction) | Bacterial growth inhibition assay | Function retained despite significant divergence; context enabled conjugate antitoxin design. |

| WW Domain Mutants [21] | N/A (Single mutants) | 97.2% were deleterious | Phage display for binding | A comprehensive sequence-function map revealed most mutations are detrimental, highlighting key conserved residues. |

| Cis-Regulatory Elements (CREs) [22] | Highly diverged (non-alignable) | Functional conservation in vivo | In vivo reporter assays (mouse/chicken) | Widespread functional conservation exists in the absence of sequence conservation, identified via synteny. |

The data indicates that functional conservation is not strictly bound by a single sequence identity threshold. In some cases, like the de novo anti-CRISPRs, function can emerge in sequences with no significant similarity to any natural protein, completely bypassing traditional evolutionary constraints [20]. In other contexts, such as the de novo toxin EvoRelE1, a 71% sequence identity was sufficient to maintain strong function, and more importantly, this sequence served as a contextual prompt for generating functional partners [20]. Furthermore, in non-coding regions, the principle breaks down entirely, with functional cis-regulatory elements showing conservation in the absence of sequence alignability, reliant instead on syntenic genomic position [22]. These examples underscore that the genomic and functional context is as critical as the percentage identity itself.

Experimental Protocols for Validating Functional Conservation

Establishing functional conservation requires rigorous experimental validation, especially when sequence identity is low. The following protocols detail key methodologies used in the cited studies to quantify protein function and validate bioactivity.

Bacterial Growth Inhibition Assay for Toxin Activity

This protocol is used to assess the functionality of generated toxin proteins, such as in the validation of the EvoRelE1 toxin [20].

- Cloning and Transformation: The gene encoding the candidate toxin protein is cloned into an inducible expression vector (e.g., pBAD or pET series). The construct is then transformed into a suitable bacterial strain (e.g., E. coli BL21).

- Culture and Induction: Primary cultures are grown to mid-log phase. The culture is then diluted and split into two aliquots. One aliquot is induced with a suitable agent (e.g., IPTG or arabinose) to express the toxin, while the other is left uninduced as a control.

- Spot Assay or Serial Dilution: Induced and uninduced cultures are serially diluted (e.g., 10-fold serial dilutions). A fixed volume of each dilution is spotted onto solid agar plates containing the inducing agent. Alternatively, growth can be monitored in liquid culture via optical density (OD600).

- Incubation and Analysis: Plates are incubated for 12-16 hours at the appropriate temperature. Cell viability is quantified by comparing the number of colonies or the growth density in the induced versus uninduced samples. A functional toxin will demonstrate a significant reduction in survival, calculated as Relative Survival (%) = (CFU induced / CFU uninduced) * 100 [20].

Phage Display with High-Throughput Sequencing for Sequence-Function Mapping

This method, used for the WW domain, allows for the parallel quantitative assessment of hundreds of thousands of protein variants [21].

- Library Construction: A diverse library of protein variants is created via synthetic oligonucleotide synthesis, encompassing single, double, and triple mutants of the target gene. The library is cloned into a phage display vector, such as for T7 bacteriophage, creating a fusion with a capsid protein.

- Moderate Selection Pressure: The phage library is subjected to rounds of selection against an immobilized target (e.g., a peptide ligand). Critically, selection pressure is moderated to avoid rapidly converging on the few best binders, thereby preserving library diversity for quantitative analysis.

- DNA Sequencing and Quantification: After several rounds of selection (e.g., rounds 3 and 6), the pooled phage DNA is prepared for high-throughput sequencing (e.g., Illumina). The frequency of each variant in the input library is compared to its frequency after selection.

- Data Analysis: An enrichment ratio for each variant is calculated as (Frequency after selection / Frequency in input). Variants with ratios >1 are enriched and likely functional, while those with ratios <1 are deleterious. This generates a high-resolution map of mutational tolerance across the entire protein sequence [21].

In Vivo Enhancer-Reporter Assay for Non-Coding Elements

This protocol validates the function of non-coding cis-regulatory elements (CREs), such as those identified as indirectly conserved between species [22].

- Candidate Enhancer Cloning: The candidate non-coding DNA sequence (e.g., a predicted enhancer from chicken) is cloned upstream of a minimal promoter driving a reporter gene, such as lacZ or GFP, in a plasmid vector.

- Generation of Transgenic Models: The constructed plasmid is used to create transgenic animal models (e.g., mouse embryos) via pronuclear injection or other methods.

- Temporal and Spatial Analysis: The expression pattern of the reporter gene is analyzed at the equivalent developmental stage from which the CRE was originally assayed (e.g., embryonic day E10.5 in mouse). This is often done via staining for β-galactosidase activity (for lacZ) or fluorescence microscopy (for GFP).

- Validation of Functional Conservation: The reporter expression pattern is compared to the expression pattern of the putative target gene in the native species. A recapitulation of the expected tissue-specific pattern in the transgenic model, despite sequence divergence, provides strong evidence for functional conservation [22].

Visualization of Concepts and Workflows

Semantic Design for Functional De Novo Proteins

The following diagram illustrates the "semantic design" workflow using a genomic language model to generate novel functional proteins based on genomic context.

Sequence-Function Relationship Spectrum

This diagram contrasts the classical view of sequence-structure-function with emerging paradigms where function is conserved despite sequence or structural divergence.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table catalogues key reagents, datasets, and computational tools essential for research in sequence-structure-function relationships.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for Protein Function Investigation

| Reagent / Resource | Type | Function and Application | Example / Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genomic Language Model | Computational Tool | Generates novel DNA sequences conditioned on a functional genomic prompt; enables semantic design. | Evo (Evo 1.5) [20] |

| SynGenome Database | Database | Provides access to over 120 billion base pairs of AI-generated sequences for semantic design across functions. | evodesign.org/syngenome/ [20] |

| Phage Display System | Experimental Platform | Links protein phenotype to genotype for high-throughput screening of variant libraries for binding function. | T7 Bacteriophage Display [21] |

| Structural Model Database | Database | Provides predicted protein structures for functional annotation and fold-space analysis. | MIP Database [15] |

| Synteny Mapping Algorithm | Computational Tool | Identifies orthologous genomic regions independent of sequence conservation. | Interspecies Point Projection (IPP) [22] |

| In Vivo Reporter Assay System | Experimental Platform | Validates the function of non-coding regulatory elements in a developmental context. | Transgenic Mouse/Chicken Models [22] |

| High-Throughput Sequencer | Instrument | Enables quantitative tracking of hundreds of thousands of protein variants in parallel during selection. | Illumina Platform [21] |

Proteins are fundamental to virtually every biological process, acting as enzymes, structural elements, and signaling molecules. Their diverse functions are inextricably linked to unique three-dimensional structures, which are determined by their amino acid sequences. The relationship between sequence, structure, and function forms a core principle of molecular biology. Mutations—variations in the amino acid sequence—can disrupt this delicate relationship by altering protein structure, stability, interactions, and ultimately, biological function. Such disruptions frequently manifest as disease, making the understanding of mutational impact crucial for both basic research and therapeutic development [23].

The challenge of interpreting missense variants remains significant in genetic medicine. While each human genome contains tens of thousands of genetic variants, only a handful are likely to disrupt protein function in ways that cause disease. Identifying these "disease-causing needles" in the vast genomic "haystack" is a central problem in clinical genomics [24]. Recent advances in artificial intelligence, structural biology, and biophysical modeling are transforming our ability to predict and understand these effects, offering new pathways for diagnosis and treatment.

Fundamental Mechanisms: How Mutations Disrupt Protein Structure

Energetic and Stability Consequences

Single amino acid substitutions can induce a spectrum of structural disturbances, primarily by altering the delicate thermodynamic balance that stabilizes the native protein fold.

- Destabilization of the Native Fold: Many disease-associated mutations reduce protein stability by disrupting favorable interactions within the folded structure. This includes the loss of stabilizing hydrogen bonds, salt bridges, or van der Waals contacts, or the introduction of steric clashes or unfavorable charge interactions. The net effect is a reduction in the free energy difference (ΔG) between the folded and unfolded states, increasing the population of non-functional or aggregation-prone unfolded or partially folded states [25].

- Perturbation of Folding Pathways: Beyond thermodynamic stability, mutations can also disrupt the kinetic accessibility of the native fold by altering critical nucleation sites or introducing non-productive interactions that trap intermediate states.

Disruption of Functional Motifs and Allostery

Mutations need not cause global unfolding to be pathogenic. Subtle changes in specific functional regions can be equally detrimental.

- Active Site Disruption: Mutations within enzyme active sites or binding pockets can directly interfere with substrate binding, cofactor recruitment, or catalytic efficiency. Even small structural shifts of key residues can abolish function.

- Allosteric Disruption: Mutations distal to active sites can propagate conformational changes through the protein scaffold, effectively "tuning" functional activity. This allosteric mechanism is increasingly recognized as a common cause of disease [23].

- Protein-Protein and Protein-Ligand Interactions: Many proteins function as part of larger complexes. Mutations at interaction interfaces can disrupt quaternary structure assembly, signal transduction, and regulatory networks [25].

Computational Methodologies for Predicting Mutational Impact

The development of reliable computational models to predict the effects of mutations has been a major focus of structural bioinformatics and computational biology. These methods can be broadly categorized into evolution-based, physics-based, and AI-driven approaches, each with distinct strengths and applications.

Evolution-Informed and AI Models

Deep generative models, such as popEVE, represent a significant advance in variant effect prediction. popEVE integrates deep evolutionary information from diverse species with human population genetic data from resources like the UK Biobank and gnomAD. This combination allows it to estimate variant deleteriousness on a proteome-wide scale, calibrating scores to reflect human-specific constraint. The model operates by:

- Learning Evolutionary Constraints: Using a deep generative model to identify patterns of mutation tolerance from billions of years of evolutionary history.

- Incorporating Population Data: Transforming evolutionary scores using human population frequency data to distinguish variants critical for human health.

- Providing Calibrated Scores: Outputting a continuous measure of deleteriousness that enables comparison across different proteins, distinguishing variants causing severe childhood disorders from those with milder effects [26] [24].

A key advantage of popEVE is its performance in real-world applications. In a cohort of approximately 30,000 patients with severe developmental disorders, popEVE analysis led to a diagnosis in about one-third of previously undiagnosed cases and identified variants in 123 novel genes linked to developmental disorders, 25 of which have since been independently confirmed [24].

Physics-Based Free Energy Calculations

Physics-based methods, such as Free Energy Perturbation (FEP), offer a complementary approach rooted in statistical thermodynamics. Protocols like QresFEP-2 provide a rigorous, physics-based alternative for quantifying the effect of point mutations on protein stability and ligand binding.

The QresFEP-2 protocol employs a hybrid-topology approach:

- System Setup: The protein is solvated in a water sphere or periodic box, and ions are added to neutralize the system.

- Hybrid Topology Construction: A single-topology representation is used for the conserved protein backbone and a dual-topology for the variable side chains of the wild-type and mutant residues.

- Alchemical Transformation: The wild-type side chain is gradually transformed into the mutant side chain via a series of non-physical intermediate states (λ windows).

- Free Energy Calculation: The change in free energy (ΔΔG) is calculated by integrating the derivative of the Hamiltonian with respect to λ across the transformation pathway. This ΔΔG value quantitatively predicts the change in protein stability or binding affinity resulting from the mutation [25].

QresFEP-2 has been benchmarked on comprehensive datasets, including nearly 600 mutations across 10 protein systems, demonstrating excellent accuracy and high computational efficiency. It is applicable to protein stability, protein-ligand binding (e.g., GPCRs), and protein-protein interactions [25].

Table 1: Comparison of Leading Computational Methods for Predicting Mutational Impact

| Method | Underlying Principle | Key Application | Key Strength | Representative Tool |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Evolutionary AI | Deep generative models trained on evolutionary sequences and population data | Proteome-wide variant prioritization and diagnosis of rare diseases | Calibrated scores that distinguish severity across genes; minimal ancestry bias | popEVE [26] |

| Physics-Based Simulation | Molecular dynamics and statistical thermodynamics | Quantitative prediction of stability changes (ΔΔG) and binding affinity for drug design | High accuracy for specific proteins; provides atomic-level insight | QresFEP-2 [25] |

| Deep Learning Structure Prediction | Transformer-based neural networks trained on known structures | Rapid generation of 3D structural models to interpret mutations in a structural context | Access to structural models for proteins with unknown experimental structures | AlphaFold [27] [23] |

Figure 1: Workflow of the popEVE model for proteome-wide variant effect prediction. The model integrates deep evolutionary information with human population data to generate calibrated deleteriousness scores [26] [24].

The Role of Advanced Structural Prediction: AlphaFold

The revolution in protein structure prediction, led by AlphaFold, has provided an unprecedented view of the structural landscape of proteomes. AlphaFold2, recognized as a solution to the 50-year protein folding problem in 2020, predicts protein structures with accuracy comparable to experimental methods [27] [28].

Applications in Mutation Research

AlphaFold models are being used to interpret the mechanistic basis of disease-causing mutations in several ways:

- Visualizing Mutations in Structural Context: Researchers can place a variant onto an AlphaFold-predicted structure to see if it localizes to a critical functional region, such as an active site, protein-protein interface, or allosteric network [29] [23].

- Guiding Experimental Design: For proteins with no experimental structure, AlphaFold models provide a reliable starting point for designing mutagenesis experiments and formulating hypotheses about molecular mechanisms of disease [28].

- Studying Protein Complexes: Subsequent versions like AlphaFold Multimer and AlphaFold 3 enable the prediction of multimeric protein assemblies, allowing researchers to assess how mutations disrupt protein-protein interactions [28] [23].

Limitations and Complementary Techniques

Despite its transformative impact, AlphaFold has limitations. It is primarily a static structure prediction tool and may not accurately capture protein dynamics, multiple conformational states, or the effects of mutations on folding pathways. As one scientist noted, AlphaFold's predictions can sometimes be ambiguous: "Is this real or is this not? It's sort of borderline... it will bullshit you with the same confidence as it would give a true answer" [28].

Therefore, AlphaFold predictions are most powerful when integrated with complementary techniques:

- Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulations: To model flexibility and time-dependent behavior.

- Experimental Structural Biology: Such as Cryo-EM and X-ray crystallography, for high-resolution validation.

- Functional Assays: Such as electrophysiology for ion channels, to confirm the physiological impact of a mutation predicted in silico [29] [23].

Experimental Validation and Workflow Integration

Computational predictions require rigorous experimental validation to confirm their biological and clinical relevance. A synergistic workflow combining computation and experiment is essential for elucidating the mechanistic link between mutation and disease.

A Protocol for Ion Channel Studies

The structure-function relationship of ion channels, which are crucial for signaling and often mutated in disease, can be systematically studied using AlphaFold3. A representative protocol involves:

- Structure Prediction and Analysis: Use AlphaFold3 to predict the structure of the wild-type and mutant ion channel complex. Analyze key structural parameters like pore radius, subunit interfaces, and ligand-binding sites [29].

- Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulations: Perform MD simulations on the predicted models to assess stability and identify conformational changes in key regions, such as the gating domain [29] [25].

- Functional Assays: Validate computational insights experimentally.

- Electrophysiology: Use patch-clamp recording to measure changes in ion conductance, activation, and inactivation properties.

- Ion Imaging: Employ fluorescence-based assays to visualize changes in ion flux in living cells [29].

- Data Integration: Correlate structural changes observed in the models with functional deficits measured in the assays to establish a causative mechanism [29].

Figure 2: An integrated computational and experimental workflow for validating the impact of mutations on ion channel function, applicable to other protein classes [29].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Materials for Studying Mutation Effects

| Reagent / Tool | Function in Research | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| AlphaFold Protein Structure Database | Provides instant access to predicted structures for over 200 million proteins, serving as a primary hypothesis-generation tool. | Visualizing the structural location of an uncharacterized missense variant in a protein of interest [27]. |

| popEVE Score | A calibrated AI-based metric for variant deleteriousness that enables prioritization of candidate mutations across the entire genome. | Triaging thousands of variants from a patient exome to identify the single most likely pathogenic candidate [26] [24]. |

| QresFEP-2 Software | An open-source, physics-based protocol for calculating the change in free energy (ΔΔG) resulting from a point mutation. | Quantitatively predicting whether a mutation in a drug target will destabilize the protein or reduce drug-binding affinity [25]. |

| Cryo-Electron Microscopy (Cryo-EM) | An experimental technique for determining high-resolution structures of proteins and complexes, often used to validate computational models. | Solving the atomic structure of a mutant ion channel complex to confirm a predicted disruption of the pore region [23]. |

| Plasmids for Site-Directed Mutagenesis | Molecular biology tools used to introduce specific mutations into a protein-coding sequence for recombinant expression. | Creating the wild-type and mutant versions of a protein for subsequent biophysical or functional characterization in cells [29]. |

Implications for Drug Discovery and Therapeutic Development

The ability to accurately predict and understand mutational impact is directly translating into advances in drug discovery and therapeutic strategies.

- Target Identification and Validation: By pinpointing causal variants and their mechanisms, tools like popEVE help identify novel drug targets for rare and common diseases. The 123 novel candidate genes identified for severe developmental disorders represent a new frontier for therapeutic exploration [26] [24].

- Personalized Medicine and Drug Design: Understanding how patient-specific mutations affect a drug target's structure allows for the design of next-generation therapeutics. For instance, if a mutation causes resistance by altering a drug-binding pocket, FEP simulations can help design a modified compound that overcomes this resistance [25].

- Enhancing Protein Therapeutics: Computational protocols can be used in reverse to design more stable and efficacious protein-based therapeutics, such as antibodies and enzymes, by predicting stabilizing mutations [25].

The integration of evolutionary AI, physics-based simulations, and accessible high-accuracy structural prediction is fundamentally transforming the study of mutational impact. Framed within the core principle of protein sequence-structure-function relationships, these technologies provide a powerful, multi-scale toolkit for deciphering the molecular etiology of disease. This integrated understanding, moving seamlessly from genetic sequence to atomic structure to physiological function, is paving the way for more precise diagnostics and targeted therapeutics, ultimately bridging the gap between genetic variation and patient health.

Methodologies in Action: Predicting Structure and Inferring Function from Sequence