Engineering Protein Thermostability: AI-Driven Methods, Practical Applications, and Future Directions for Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive overview of modern strategies for enhancing protein thermostability, a critical challenge in developing effective biopharmaceuticals and industrial enzymes.

Engineering Protein Thermostability: AI-Driven Methods, Practical Applications, and Future Directions for Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of modern strategies for enhancing protein thermostability, a critical challenge in developing effective biopharmaceuticals and industrial enzymes. We explore the fundamental biophysical principles governing thermal stability, detail cutting-edge methodologies from ancestral sequence reconstruction to machine learning and reinforcement learning, and address key troubleshooting considerations for balancing stability with activity. By comparing the performance and validation of various computational and experimental approaches, this review serves as a strategic guide for researchers and drug development professionals seeking to design more stable, robust proteins for therapeutic and biomedical applications.

The Biophysical Basis of Protein Thermostability: From Fundamental Principles to Evolutionary Insights

Understanding the Free Energy Landscape of Protein Folding and Unfolding

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is a protein free energy landscape and why is it important? The free energy landscape is a cornerstone concept in protein folding that visually represents the stability of different protein conformations. It plots the free energy of the protein as a function of one or more reaction coordinates (like the fraction of native contacts, Q) [1]. A globally funneled landscape explains how proteins can fold rapidly to their native state despite the astronomically large number of possible conformations, thus resolving Levinthal's paradox [1] [2]. A steep, smooth funnel indicates a strong energetic bias toward the native state, while a rugged landscape with kinetic traps can lead to misfolding or slow folding kinetics [2]. This framework is essential for understanding not just folding, but also biomolecular binding and aggregation [1].

2. What is the difference between a "funneled" and a "rugged" landscape? A funneled landscape has an overall downhill slope toward the native state, guiding the protein efficiently to its stable conformation. In contrast, a rugged landscape contains many non-native local minima and energy barriers [2]. Proteins can become temporarily trapped in these minima (kinetic traps), which slows down the folding process. The "roughness" of the landscape is influenced by factors like non-native interactions, and the ratio of the folding transition temperature (Tf) to the glass transition temperature (Tg) provides a quantitative measure of this frustration [2].

3. How does the free energy landscape explain the behavior of Intrinsically Disordered Proteins (IDPs)? IDPs, like the pKID domain studied, have a free energy landscape that is funneled but significantly shallower than that of ordered proteins [1]. Research shows that while a typical ordered protein (e.g., HP-35, WW domain) has a landscape slope of about -50 kcal/mol, an IDP like pKID has a shallower slope of about -24 kcal/mol [1]. This means the energetic drive to adopt a single native structure is weaker, explaining their disordered nature in isolation. Upon binding to a partner (like KIX binding to pKID), the landscape becomes steeper (slope of -54 kcal/mol) due to new intermolecular interactions, enabling the IDP to fold [1].

4. What are the key order parameters for constructing a free energy landscape? Choosing the right order parameters (or reaction coordinates) is critical for meaningful landscape visualization. Common choices include:

- Fraction of Native Contacts (Q): Measures the proportion of atom-atom contacts in a given configuration that are also present in the native structure. A value of 1 indicates the fully folded state [1].

- Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD): Measures the average distance between the atoms of a structure and a reference structure (usually the native fold).

- Radius of Gyration (Rg): Describes the overall compactness of the protein structure [3]. Often, two-dimensional landscapes are constructed using a combination of these parameters, such as RMSD versus Rg, to better distinguish between different conformational states [3].

5. What are common challenges in free energy landscape calculations and how can they be overcome? A major challenge is the timescale gap: the time scales of folding/unfolding events often far exceed what is practical with standard molecular dynamics (MD) simulations due to free energy barriers [4].

- Solution: Use enhanced sampling methods. These are algorithms designed to accelerate the exploration of configuration space and overcome energy barriers. The field is actively working on making these methods more reproducible and less dependent on expert tuning [4]. Another challenge is the identification of optimal reaction coordinates, which is often cumbersome [4].

- Solution: Careful analysis and the use of dimensionality reduction techniques like Principal Component Analysis (PCA) can help identify meaningful collective variables that capture the essential dynamics of the folding process.

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Inadequate Sampling of Protein Conformations

Problem: The resulting free energy landscape appears poorly defined, with missing intermediate states or a lack of clear funnels. This often occurs because the simulation trajectory did not capture a sufficient number of folding and unfolding events.

Solution: Ensure extensive conformational sampling.

- Action 1: Run longer simulations. If resources are limited, consider using multiple, shorter parallel simulations starting from different initial configurations.

- Action 2: Employ enhanced sampling techniques. Methods like metadynamics, umbrella sampling, or replica exchange MD can force the system to explore high-energy regions and cross barriers more efficiently [4].

- Action 3: Save a large number of frames during your simulation. As a general guideline, at least 10,000 frames are often required to obtain a reasonable representation of the free energy landscape for a flexible protein [3].

Issue 2: Noisy or Non-Reproducible Landscapes

Problem: The landscape changes significantly between independent simulation runs, or minor conformational states appear over-represented.

Solution: Improve statistical robustness and validation.

- Action 1: Replicate your simulations. Run multiple independent trajectories to ensure the observed landscape features are consistent and not artifacts of a single run.

- Action 2: Use a common binning scheme and range when comparing multiple landscapes. This ensures that differences are due to the system's properties and not variations in data processing [3].

- Action 3: Validate your landscape with experimental data. If available, compare the predicted stable states and their populations with experimental data from NMR, FRET, or folding rate measurements.

Issue 3: Incorrect Interpretation of Landscape Features

Problem: Confusing the potential of mean force (free energy profile, F(Q)) with the effective energy landscape (f(Q)).

Solution: Understand the distinction between different landscape definitions.

- Action 1: Recall that the effective energy landscape,

f(Q) = E_u + G_solv, has a globally funneled shape because it lacks configurational entropy [1]. - Action 2: Remember that the free energy profile,

F(Q) = -k_B T log P(Q), includes the configurational entropy. It is this profile,F(Q), that shows a clear barrier between the unfolded and folded states for two-state folders [1]. - Diagnostic Table:

| Feature | Effective Energy Landscape (f(Q)) | Free Energy Profile (F(Q)) |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Average of (Gas-phase energy + Solvation free energy) over configurations at Q [1] | -k_B T log(Probability of Q) |

| Includes Entropy? | No | Yes |

| Typical Shape | Globally funneled (downhill slope) | Double-well with a transition barrier |

| Primary Use | Understanding the overall energetic bias toward the native state | Studying thermodynamics (state populations) and kinetics (barrier heights) |

Experimental Protocols & Data Presentation

Protocol 1: Constructing a Free Energy Landscape from MD Simulations

This protocol outlines the steps for generating a free energy landscape using simulation data and the Boltzmann inversion method [3].

- Run Molecular Dynamics Simulations: Perform MD simulations that sufficiently sample the unfolded, folded, and potential intermediate states of the protein.

- Extract Order Parameters: For each saved frame in the trajectory, calculate two order parameters (e.g., RMSD and Rg, or the projection on the first two principal components).

- Create a 2D Histogram: Bin the two calculated variables to create a 2D histogram. The count in each bin,

n_i, represents the population of that region of conformational space. - Perform Boltzmann Inversion: Calculate the change in free energy,

Δε_i, for each bin using the formula:Δε_i = -k_B T ln(n_i / n_max)wherek_Bis Boltzmann's constant, T is the temperature, andn_maxis the population of the most occupied bin [3]. - Normalize and Plot: Subtract the maximum

Δε_ivalue so that the most probable state has the most negative free energy. Plot the resulting landscape as a 3D surface or a 2D contour plot.

Protocol 2: Quantifying Landscape "Funneledness" for Ordered vs. Disordered Proteins

This methodology, based on a 2019 Scientific Reports paper, allows for the quantitative comparison of landscape slopes [1].

- Simulate and Calculate Q: Perform all-atom MD simulations for the protein of interest (e.g., an ordered protein like HP-35 and a disordered protein like pKID, both free and bound to its partner KIX).

- Compute Effective Energy: For each configuration

r, compute the effective energyf(r) = E_u(r) + G_solv(r), whereE_uis the gas-phase energy andG_solvis the solvation free energy [1]. - Calculate f(Q): Average

f(r)over all configurations that have a specific value of the fraction of native contacts,Q. Repeat for all Q between 0 and 1. - Determine the Slope: Plot

f(Q)versusQand perform a linear fit. The slope of this line quantitatively represents the strength of the energetic bias toward the native state.

Table: Quantitative Comparison of Free Energy Landscape Slopes [1]

| Protein | Type | Condition | Landscape Slope (kcal/mol) | Functional Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HP-35 | Ordered α-helical | Isolated | ~ -50 | Steep funnel enabling fast, autonomous folding |

| WW Domain | Ordered β-sheet | Isolated | ~ -50 | Steep funnel enabling fast, autonomous folding |

| pKID | Intrinsically Disordered | Isolated | ~ -24 | Shallow funnel, explaining disordered nature |

| pKID-KIX | Complex (IDP bound) | Bound | ~ -54 | Steep funnel induced by binding, enabling folding upon binding |

Workflow Diagram: Free Energy Landscape Analysis

Workflow for constructing and analyzing a free energy landscape from simulation data.

Free Energy Landscape Models Diagram

Conceptual models of free energy landscapes, each with different implications for folding kinetics and mechanisms [2].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Computational Tools and Resources

| Item | Function/Brief Explanation | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| MD Simulation Software (e.g., GROMACS, AMBER, NAMD) | Generates the atomic-level trajectory of the protein in solution by numerically solving Newton's equations of motion. | Producing the raw conformational data needed to calculate order parameters and construct landscapes [3]. |

| Free Energy Landscape Tool (e.g., MD DaVis) | Software specifically designed to process simulation data, perform Boltzmann inversion, and create interactive plots of free energy landscapes [3]. | Taking RMSD and Rg data from a trajectory file and generating a publishable-quality landscape plot. |

| Stability Prediction Tools (e.g., FoldX, Rosetta-ddG, PoPMuSiC) | Algorithms that predict the change in folding free energy (ΔΔG) upon mutation, often based on empirical energy functions or machine learning [5]. | Rapidly screening point mutations to identify those likely to improve thermostability before experimental validation [6] [5]. |

| AI Thermostability Models (e.g., SCSAddG) | Deep learning models that predict thermostability trends from protein sequence, potentially capturing complex, non-obvious patterns [5]. | Guiding protein engineering campaigns by predicting which mutation trends lead to higher stability, reducing experimental screening load [5]. |

| Molecular Integral-Equation Theory | A computational method for estimating the solvation free energy (G_solv) of a protein configuration, a key component of the effective energy f(r) [1]. | Quantifying the solvation contribution for each snapshot in an MD trajectory when constructing a quantitative f(Q) landscape [1]. |

Troubleshooting Guide: FAQs on Protein Stabilization

FAQ 1: How significant is the contribution of hydrophobic interactions to overall protein stability compared to other forces?

Hydrophobic interactions are a dominant force in stabilizing the native, folded structure of globular proteins. Experimental data suggests that for a range of proteins, hydrophobic interactions contribute approximately 60 ± 4% to the overall stability, while hydrogen bonds contribute about 40 ± 4% [7]. The stability gained from burying a hydrophobic group is quantifiable; on average, burying a –CH₂– group contributes 1.1 ± 0.5 kcal/mol to the folding free energy [7]. It is important to note that this contribution can vary with protein size, being less in small proteins and greater in larger ones [7].

Table 1: Energetic Contribution of Hydrophobic Interactions

| Measurement | Energetic Contribution | Context / Conditions |

|---|---|---|

| Average contribution per –CH₂– group buried | 1.1 ± 0.5 kcal/mol [7] | Based on 148 hydrophobic mutants in 13 proteins |

| Contribution in a small protein (VHP, 36 residues) | 0.6 ± 0.3 kcal/mol per –CH₂– group [7] | Ile/Val to Ala mutations |

| Contribution in a large protein (VlsE, 341 residues) | 1.6 ± 0.3 kcal/mol per –CH₂– group [7] | Ile to Val mutations |

| Total hydrophobic contribution to VHP stability | ~40 kcal/mol [7] | Major contributors: Phe, Met, Leu residues |

Troubleshooting Note: If your protein exhibits lower-than-expected stability, consider using algorithms to optimize the hydrophobic core by replacing buried residues with longer or bulkier hydrophobic side chains to improve packing, a strategy that has successfully increased melting points by over 15°C [6].

FAQ 2: Are salt bridges always stabilizing for proteins?

No, salt bridges do not always confer stability and can sometimes even destabilize the folded state. The net stabilizing effect of a salt bridge is the sum of favorable Coulombic attraction between opposite charges and often unfavorable desolvation penalties incurred when the charged groups are removed from water and placed in the protein's interior [8] [9]. The strength of electrostatic interactions is highly context-dependent, influenced by the local environment, the dynamic flexibility of the groups, and the interactions in the unfolded state [8]. While not always a dominant factor in the thermodynamic stability of mesophilic proteins, they are frequently critical for the stability of proteins from thermophiles and hyperthermophiles, which often possess more, and sometimes networked, salt bridges [8].

Troubleshooting Note: When engineering salt bridges for enhanced thermostability, consider evolutionary stability. Analyses suggest that introducing salt bridges where at least one of the amino acid positions is evolutionarily conserved is more likely to improve stability [10].

FAQ 3: What is the primary mechanism by which disulfide bonds stabilize proteins?

The classical view is that disulfide bonds primarily stabilize proteins by reducing the conformational entropy (disorder) of the unfolded state, making the unfolded chain less favorable and thereby shifting the equilibrium toward the folded state [11]. However, more recent research indicates that this is an oversimplification. Enthalpic effects and specific interactions within the native state also play significant roles and cannot be neglected [11]. The stabilizing effect can be substantial, with the introduction of multiple engineered disulfide bonds leading to a marked increase in stability [11].

Troubleshooting Note: The stability conferred by a disulfide bond can be context-dependent. Research on model proteins suggests that a disulfide bond can rigidify the structure and amplify the destabilizing effect of a mutation some distance away, whereas the protein is more flexible and accommodating of the mutation without the disulfide [12].

FAQ 4: Why is my designed salt bridge not stabilizing the protein as predicted?

This is a common challenge in protein engineering. The failure can be attributed to several factors:

- High Desolvation Penalty: The energy cost of removing the charged atoms from water (desolvation) may outweigh the favorable energy from the charge-charge interaction in the folded state [9].

- Suboptimal Geometry: The spatial arrangement and distance between the charged groups may not be optimal for a strong electrostatic interaction [10].

- Lack of Evolutionary Context: Introducing a salt bridge at a position that is not evolutionarily constrained may disrupt existing, finely-tuned interactions. Focusing on positions where charged residues are evolutionarily conserved can improve success rates [10].

- Altered Unfolded State: Electrostatic interactions might also be present in the unfolded state, which would diminish the net stabilizing effect upon folding [8].

FAQ 5: The measured stabilization from my disulfide bond mutant does not match theoretical predictions. Why?

Current theoretical models often fail to accurately predict the quantitative stabilization from disulfide bonds. The discrepancies arise from:

- Deficiencies in Theoretical Models: Models may not fully account for all enthalpic and native-state effects [11].

- Subtle Stabilizing Factors: The measured change in stability (ΔΔG) is against a backdrop of numerous other subtle stabilizing and destabilizing interactions in both the native and denatured states that the disulfide bond may also affect [11].

- Altered Denatured State: The disulfide bond can sometimes stabilize a compact denatured state, which reduces the net free energy change between the folded and unfolded states [11].

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Protocol 1: Quantifying Hydrophobic Contribution via Site-Directed Mutagenesis

This protocol outlines how to measure the contribution of a specific hydrophobic residue to protein stability.

- Design Mutants: Use site-directed mutagenesis to create variants where a buried hydrophobic residue (e.g., Leu, Ile, Phe) is mutated to Ala, Val, or another smaller residue. This removes a specific amount of hydrophobic surface area (–CH₂– or –CH₃ groups).

- Protein Purification: Express and purify the wild-type and mutant proteins to homogeneity.

- Equilibrium Denaturation:

- Prepare a series of solutions with increasing concentrations of a chemical denaturant like urea or guanidine hydrochloride (GuHCl).

- Incubate the protein in each denaturant solution until equilibrium is reached.

- Use a spectroscopic method like Circular Dichroism (CD) at 222 nm (for α-helical content) or fluorescence spectroscopy (for changes in the environment of tryptophan residues) to monitor the unfolding transition [7].

- Data Analysis:

- Fit the data to a two-state unfolding model to determine the free energy of unfolding in water, ΔG(H₂O), and the denaturant concentration at the midpoint of the transition, [Denaturant]₁/₂ [7].

- The change in stability, Δ(ΔG), is calculated as ΔG(mutant) - ΔG(wild-type). A negative value indicates destabilization.

- The Δ(ΔG) for a mutation like Ile to Val reports the stability contribution of the single –CH₂– group removed [7].

The workflow for this experimental approach is summarized in the following diagram:

Protocol 2: Assessing Disulfide Bond Stability via Redox Denaturation

This protocol determines the stabilizing effect of a disulfide bond by comparing the stability of the oxidized (bond intact) and reduced (bond broken) protein.

- Protein in Oxidized Form: Use the native, disulfide-bonded protein.

- Reduction of Disulfide Bond: Treat the protein with a reducing agent like Dithiothreitol (DTT) or Tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine (TCEP) to break the disulfide bond.

- Chemical Denaturation: As in Protocol 1, perform equilibrium denaturation experiments using urea or GuHCl on both the oxidized and reduced protein forms.

- Stability Comparison: Monitor unfolding via CD or fluorescence. The difference in ΔG(H₂O) between the oxidized and reduced forms, ΔΔGₒₓ₋ᵣₑd, represents the stabilizing contribution of the disulfide bond [12].

- Control for Alkylation (Optional): After reduction, the cysteine thiols can be alkylated with iodoacetamide to prevent re-oxidation or disulfide scrambling during the experiment [13].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Protein Stability Research

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Key Details |

|---|---|---|

| Urea & Guanidine HCl (GuHCl) | Chemical denaturants for equilibrium unfolding studies. | Used to perturb the folded-unfolded equilibrium. The mid-point of the transition ([Denaturant]₁/₂) and the m-value (cooperativity) are key stability parameters [7]. |

| Circular Dichroism (CD) Spectrometer | To monitor secondary structure changes during unfolding. | Measures loss of α-helical signal (at 222 nm) or β-sheet structure as a function of denaturant or temperature [7] [12]. |

| Fluorescence Spectrophotometer | To monitor changes in the local environment of aromatic residues. | Tryptophan fluorescence is a sensitive probe for its burial (folded) or exposure (unfolded) to solvent [7]. |

| Dithiothreitol (DTT) / TCEP | Reducing agents to break disulfide bonds. | Used to assess the specific contribution of a disulfide bond to stability by comparing reduced vs. oxidized protein forms [12] [13]. |

| Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit | To create specific point mutations (e.g., Ile to Val). | Essential for probing the role of individual residues, such as those in the hydrophobic core or forming salt bridges [7] [6]. |

| Protein Disulfide Isomerase (PDI) | Enzyme to study disulfide bond formation and isomerization. | Used in enzymatic assays to understand the dynamics of disulfide bond formation and rearrangement during folding [13]. |

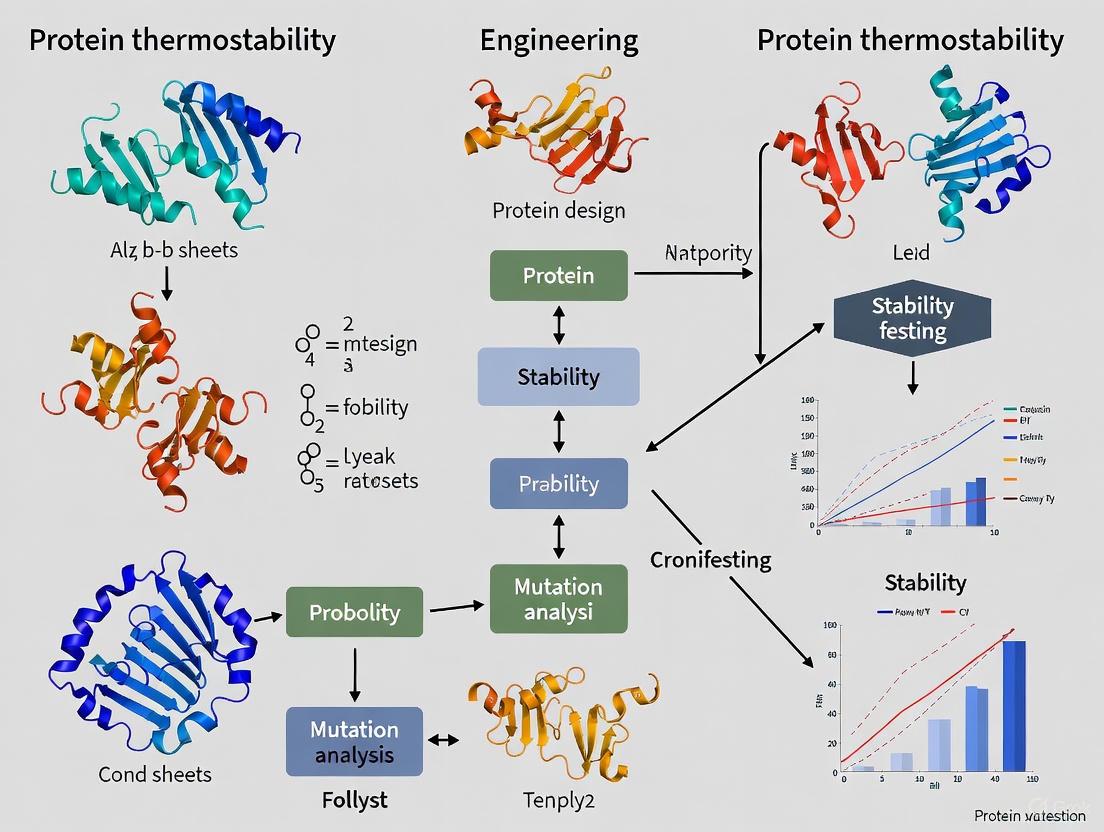

Stability Engineering Workflow

The following diagram integrates the concepts of hydrophobic engineering, salt bridge engineering, and disulfide bond engineering into a general workflow for improving protein thermostability.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the fundamental thermodynamic strategies that thermophilic proteins use to achieve high thermostability?

Thermophilic proteins achieve higher melting temperatures (Tm) through distinct thermodynamic methods. A comparative analysis of stability curves—which plot the free energy of stabilization (ΔG) against temperature—reveals three primary strategies [14]:

- Method I: Raising ΔG at all temperatures. This is the most commonly observed strategy, where the entire stability curve is elevated, resulting in a higher ΔG at every temperature, including the organism's habitat temperature.

- Method II: Broadening the stability curve. This is achieved by reducing the change in heat capacity (ΔCp) upon unfolding, which widens the curve and pushes the denaturation temperature higher.

- Method III: Shifting the curve to the right. This involves lowering the change in entropy (ΔS) of folding, which shifts the temperature of maximum stability (Ts) to a higher value.

On average, thermophilic proteins have a Tm that is 31.5°C higher and a conformational stability (ΔG) that is 8.7 kcal mol⁻¹ greater than their mesophilic counterparts [14].

FAQ 2: What are the key structural and sequence-based factors that contribute to a protein's thermostability?

Enhanced thermostability is not the result of a single factor but rather a combination of several minor structural modifications [15]. Key factors identified through comparative studies include [15] [16]:

- Increased Electrostatic Interactions: Thermophilic proteins often show a significant increase in salt bridges (ion pairs) and hydrogen bonds, particularly main-chain-to-main-chain hydrogen bonds, which stabilize the native structure.

- Optimized Amino Acid Composition: There is a tendency for thermophilic proteins to have a higher frequency of hydrophobic residues and a lower frequency of certain polar residues like Ser, Asn, Gln, and Cys. Proline is also more common, which can reduce the entropy of the unfolded state.

- Improved Core Packing: A more compact and better-packed hydrophobic core, with a reduction in the volume of internal cavities, contributes to stability.

- No Single Strategy: It is crucial to note that different proteins utilize different combinations of these strategies, and there is no universal rule for achieving thermostability.

FAQ 3: My engineered thermostable protein is inactive at lower temperatures. What could be the cause?

This is a classic challenge known as the stability-activity trade-off [17]. Increased rigidity is often necessary for thermal stability, but it can come at the cost of reduced catalytic activity at lower temperatures. This is because enzymatic activity often requires a degree of flexibility for substrate binding and product release. Computational studies using methods like Vibrational Energy Diffusivity (VED) have shown that thermophilic proteins can exhibit different patterns of residue flexibility and communication compared to mesophilic proteins [18]. Engineering efforts must therefore strike a balance, optimizing stability without overly restricting the conformational dynamics essential for function.

FAQ 4: What advanced experimental methods are available for probing the mechanisms of thermostability?

Researchers can employ a suite of biophysical and computational techniques [14] [18]:

- Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC): Directly measures the heat capacity change during unfolding, providing key thermodynamic parameters like Tm and ΔH.

- Circular Dichroism (CD) Spectroscopy: Tracks changes in secondary structure as a function of temperature or denaturant concentration.

- Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulations: Provides atomic-level insights into protein flexibility, dynamics, and unfolding pathways at different temperatures.

- Vibrational Energy Diffusivity (VED): A computational method that maps vibrational energy transfer between residues, helping identify key regions involved in thermal resistance and conformational stability.

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Insufficient Thermostability in an Engineered Enzyme You have engineered a protein for higher thermostability, but its melting temperature (Tm) remains too low for the intended industrial application.

| Step | Action | Rationale & Technical Details |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Diagnosis | Determine the current stability curve via DSC. Calculate ΔG, ΔH, Tm, and ΔCp. | Establishes a quantitative baseline. Identifying which thermodynamic parameter (e.g., ΔG, ΔCp) is suboptimal helps select the right engineering strategy [14]. |

| 2. In Silico Analysis | Perform a comparative sequence and structure analysis with a natural thermophilic homologue (if available). | Look for differences in: (a) Ion pairs and hydrogen bonds in the core and on the surface [15] [16]; (b) Core packing and cavity volume; (c) Proline content in loops; (d) Surface exposed hydrophobic areas [17]. |

| 3. Engineering Strategy | Use the analysis to design site-directed mutants. | To increase ΔG (Method I): Introduce mutations that add hydrogen bonds or salt bridges. To lower ΔCp (Method II): Optimize the hydrophobic core packing to reduce the exposed non-polar surface area upon unfolding [14]. |

| 4. Validation | Express and purify the mutant proteins. Characterize Tm and activity. | High-throughput screening methods and automated protein evolution platforms can rapidly test thousands of variants for both stability and function [19] [20]. |

Problem: Protein Aggregation at High Temperatures The protein forms aggregates when incubated at elevated temperatures, leading to loss of function.

| Step | Action | Rationale & Technical Details |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Confirmation | Use size-exclusion chromatography (SEC) or dynamic light scattering (DLS) post-incubation. | Confirms that the loss of soluble protein is due to aggregation and not just unfolding. |

| 2. Surface Analysis | Identify and neutralize exposed hydrophobic patches on the protein surface. | Surface hydrophobicity can drive intermolecular interactions leading to aggregation. Introduce charged residues (e.g., Lys, Glu, Asp) or create surface salt bridges to improve solubility [16] [17]. |

| 3. Redesign Strategy | If no natural thermophilic template exists, use computational protein design or machine learning. | Modern tools can predict stability-enhancing mutations. Machine learning models, trained on datasets of thermophilic and mesophilic proteins, can guide the exploration of sequence space more efficiently than random mutagenesis [21] [17]. |

Data Presentation: Key Differentiating Factors

Table 1: Amino Acid Composition Differences Between Thermophilic and Mesophilic Proteins Data derived from a comparative study of 60 thermophilic proteins and their mesophilic homologues [16].

| Amino Acid | Trend in Thermophiles | Proposed Structural Role |

|---|---|---|

| Glu, Pro | Significantly Increased | Proline reduces loop flexibility; Glu participates in salt bridges and hydrogen bonding networks. |

| His, Ser, Asn, Gln, Cys | Significantly Decreased | These residues are thermolabile (Asn, Gln can deamidate; Cys can oxidize) or can destabilize secondary structures. |

| Hydrophobic Residues (e.g., Ile, Leu, Val) | Increased | Improves hydrophobic core packing and enhances the hydrophobic effect. |

| Charged Residues | Overall Increase | Facilitates the formation of a higher number of ion pairs (salt bridges) and hydrogen bonds. |

Table 2: Comparative Structural and Interaction Profiles Summary of key structural factors identified through comparative analyses [15] [16].

| Structural Feature | Observation in Thermophiles | Statistical Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Main Chain Hydrogen Bonds | Increased | Yes |

| Ion Pairs (Salt Bridges) | Increased | Yes |

| Polar Contribution to Surface Area | Similar | No |

| Nonpolar Contribution to Surface Area | Similar | No |

| Compactness | Similar | No |

| Internal Cavities | Decreased | Often Observed |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Determining the Protein Stability Curve by Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC)

Principle: DSC directly measures the heat capacity of a protein solution as it is heated, allowing for the determination of the temperature-induced unfolding transition and the calculation of key thermodynamic parameters [14].

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Dialyze the purified protein (>0.5 mg/mL) into an appropriate buffer. Ensure the buffer composition is identical for the sample and reference cells.

- Instrument Calibration: Calibrate the DSC instrument for baseline stability, temperature, and cell capacity according to the manufacturer's instructions.

- Data Acquisition: Load the protein solution and reference buffer into the cells. Scan at a constant heating rate (e.g., 1°C/min) over a temperature range that encompasses the entire unfolding transition.

- Data Analysis:

- Subtract the buffer-buffer baseline scan from the protein-buffer scan.

- Determine the melting temperature (Tm) at the midpoint of the transition peak.

- Calculate the enthalpy of unfolding (ΔH) by integrating the area under the transition peak.

- The heat capacity change (ΔCp) can be estimated from the difference in baselines of the native and denatured states.

- Fit the data to the modified Gibbs-Helmholtz equation to construct the stability curve and obtain ΔG at any temperature (T) [14]:

Protocol 2: Comparative Sequence and Structure Analysis for Thermostability Engineering

Principle: By comparing a target protein to a thermostable homologue, one can identify stabilizing features to engineer into the target.

Procedure:

- Homologue Identification: Use BLASTP against the PDB to find a high-quality crystal structure of a thermophilic homologue of your target mesophilic protein [16].

- Structure Alignment: Superimpose the three-dimensional structures of the mesophilic and thermophilic proteins using software like PyMOL or Swiss-PDB Viewer.

- Analysis of Key Features:

- Salt Bridges: Calculate ion pairs (oppositely charged residues where atoms are within 4.0 Å). Note any additional networks in the thermophile.

- Hydrogen Bonds: Use a program like DSSP to enumerate main-chain and side-chain hydrogen bonds [16].

- Core Packing: Analyze the size and distribution of internal cavities. A reduction in cavity volume often correlates with stability.

- Amino Acid Substitutions: Map the sequence alignment onto the structures. Pay special attention to substitutions that introduce more Pro, Arg, or Glu, or remove Asn, Gln, or Cys in the thermophile [16].

- Mutation Design: Based on the analysis, design point mutations in the mesophilic protein to incorporate the identified stabilizing features from the thermophile.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Thermostability Engineering

| Reagent / Method | Function in Research | Key Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| Differential Scanning Calorimeter (DSC) | Directly measures the heat capacity change during protein unfolding, providing Tm, ΔH, and ΔCp. | Essential for constructing protein stability curves and determining the thermodynamic strategy of stabilization [14]. |

| Circular Dichroism (CD) Spectrometer | Monitors changes in secondary structure during thermal or chemical denaturation. | A workhorse for rapidly assessing Tm and confirming the two-state nature of the unfolding transition [14]. |

| Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulation Software (e.g., GROMACS) | Computes the movements of atoms in a protein over time at different temperatures. | Provides atomic-level insight into flexibility, unfolding pathways, and the role of specific residues in stability [18]. |

| Continuous Evolution Systems (e.g., OrthoRep) | Enables continuous, automated mutagenesis and selection of proteins in yeast. | Allows for large-scale exploration of protein sequence space to discover highly stable and functional variants with minimal human intervention [20]. |

| Machine Learning Guided Design Tools | Predicts stability-enhancing mutations based on learned patterns from protein databases. | Overcomes the limitation of limited understanding in sequence-function relationships, enabling more intelligent and efficient protein engineering [21] [17]. |

Experimental Workflow Visualization

Diagram 1: Thermostability engineering workflow depicting an iterative cycle of analysis, design, and experimental validation.

Diagram 2: Thermostability strategies map showing how structural mechanisms link to thermodynamic outcomes.

Ancestral Sequence Reconstruction (ASR) as an Evolutionary Guide to Stability

FAQs: Core Concepts and Common Challenges

What is Ancestral Sequence Reconstruction (ASR) and how can it guide protein engineering?

ASR is a technique used in molecular evolution to computationally infer the sequences of ancient genes from a multiple sequence alignment of modern descendants, and then experimentally "resurrect" those proteins for study [22]. For protein engineering, ASR serves as a powerful guide because resurrected ancestral proteins often exhibit enhanced thermostability, catalytic activity, and catalytic promiscuity compared to their modern counterparts [22] [23]. This provides engineers with stable, robust scaffolds that are more tolerant to mutations aimed at introducing new functions.

Why do my reconstructed ancestral proteins show poor expression or solubility?

This is a common experimental hurdle. Potential causes and solutions include:

- Incorrect Inferred Sequence: The reconstruction may contain errors at ambiguous residue positions. Solution: Generate and test a set of plausible alternative sequences (often called a "posterior sample") for the same node to find a functional variant [22] [24].

- Incompatibility with Modern Host: The ancestral protein's expression requirements (e.g., codon usage, co-factors) may not be optimal in your lab host (e.g., E. coli). Solution: Consider codon optimization or trying different expression strains and conditions [25].

- Methodological Bias: The assumptions of the phylogenetic model or the composition of your input sequence alignment can bias the reconstruction [25]. Solution: Validate your findings by reconstructing the same node using different methods (e.g., Maximum Likelihood and Bayesian Inference) and compare the resulting proteins [22].

Does the high thermostability of some ancestral proteins prove that ancient life was thermophilic?

Not conclusively. While many ASR studies have resurrected thermostable proteins that support the hypothesis of a thermophilic last universal common ancestor (LUCA) [25], this interpretation requires caution. The observed thermostability can sometimes be influenced by the reconstruction methodology itself [22] [25]. It is crucial to complement ASR findings with geological and geochemical data to build a robust picture of ancient environments.

What is the difference between "Ancestral Superiority" and a simple "Consensus" sequence?

The "ancestral superiority" observed in some studies refers to the phenomenon where resurrected ancestors are more stable or robust than any of the modern sequences used to reconstruct them [22]. This is different from a consensus sequence, which is a simple majority vote at each position. ASR uses a phylogenetic model that accounts for evolutionary relationships and branch lengths, not just frequency. The superior stability from ASR is thought to arise because the method integrates stabilizing mutations that arose independently across different evolutionary lineages, resulting in an additive effect [23].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Addressing Low Thermostability in Resurrected Ancestors

Problem: Your resurrected ancestral protein shows lower-than-expected thermal stability, failing to provide a stable scaffold for engineering.

| Troubleshooting Step | Action & Description |

|---|---|

| Verify Prerequisites | Confirm that the protein is pure, properly folded, and that the functional assay is working correctly with a positive control (e.g., a modern thermophilic homolog). |

| Inspect MSA and Tree | The Multiple Sequence Alignment (MSA) and phylogenetic tree are the foundations of ASR. Re-examine the MSA for errors and ensure the phylogenetic tree topology is biologically reasonable and well-supported [25] [24]. |

| Reconstruct with Alternate Methods | Rebuild the ancestor using a different statistical method (e.g., switch from Maximum Likelihood to a Bayesian approach) or with a different set of modern sequences. Compare the stability of the resulting proteins [22] [23]. |

| Check for Key Stabilizing Residues | Manually inspect or use molecular dynamics simulations to see if known stabilizing features (e.g., salt bridges, improved core packing, shortened loops) are present in your ancestor compared to a more stable reference [25]. |

| Test Posterior Sample | Generate and express a small set (e.g., 5-10) of alternative sequences for the same node that account for statistical uncertainty in the reconstruction. Often, the phenotype (stability) is conserved even if the genotype varies [22] [24]. |

Guide 2: Troubleshooting Functional Inactivity

Problem: The resurrected ancestral protein expresses well but lacks the expected catalytic or ligand-binding function.

| Troubleshooting Step | Action & Description |

|---|---|

| Confirm Correct Cofactors | Ensure that all necessary metal ions, coenzymes, or prosthetic groups are present in the assay buffer. Ancestral cofactor requirements might differ from modern proteins. |

| Test Function at Different Temperatures | The ancestor's temperature-activity profile may be different. Assay function across a broad temperature range, including higher temperatures that might match its proposed ancient environment [25]. |

| Investigate Conformational Dynamics | Function is often linked to protein dynamics. Use techniques like Hydrogen-Deuterium Exchange Mass Spectrometry (HDX-MS) or molecular dynamics simulations to see if the ancestor has restricted dynamics that might impair functional motions [24]. |

| Reconstruct Deeper Node | The function of interest might have emerged earlier in evolution. Try reconstructing and testing a deeper, more ancient ancestor to find a timepoint before the function was specialized or lost [24]. |

| Validate with Key Historical Mutations | Identify the specific historical mutations that led to the modern function. Introduce these "key historical mutations" into the inactive ancestor to see if function is restored, confirming the evolutionary path [24]. |

Essential Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Basic Workflow for Ancestral Sequence Reconstruction and Validation

This protocol outlines the standard pipeline for inferring and experimentally characterizing an ancestral protein [22] [24] [26].

- Sequence Collection & Curation: Collect a broad and diverse set of homologous protein sequences from public databases (e.g., UniProt, NCBI). Avoid over-representation of any specific clade.

- Multiple Sequence Alignment (MSA): Align sequences using a tool like MAFFT or Clustal Omega. Manually inspect and refine the alignment, as errors here propagate through the entire analysis.

- Phylogenetic Tree Inference: Construct a phylogenetic tree from the MSA using software like IQ-TREE (Maximum Likelihood) or MrBayes (Bayesian Inference). Select the best-fit model of evolution (e.g., LG, WAG) using model-testing programs.

- Ancestral Sequence Inference: Using the tree and MSA, infer the sequences at internal nodes. Common tools include CodeML (PAML), FastML, or IQ-TREE. Output the most likely sequence and, if possible, a set of plausible alternatives.

- Gene Synthesis & Cloning: The inferred ancestral sequences are typically synthesized de novo due to a lack of exact modern DNA templates, and cloned into an appropriate expression vector.

- Protein Expression & Purification: Express the protein in a suitable host (e.g., E. coli) and purify using standard chromatography methods (e.g., Ni-NTA affinity, size exclusion).

- Biophysical & Biochemical Characterization:

- Thermostability: Measure the melting temperature ((T_m)) using differential scanning fluorimetry (DSF) or calorimetry (DSC).

- Activity: Perform enzyme kinetics assays ((k{cat}), (Km)) or ligand-binding assays.

- Structure (Optional): If resources allow, determine the 3D structure via X-ray crystallography or cryo-EM to provide mechanistic insights [27].

Diagram: ASR Experimental Workflow

Data Presentation: Key Findings from ASR Studies

Table 1: Properties of Selected Resurrected Ancestral Proteins

| Protein & Approximate Age | Key Findings & Properties | Implications for Stability & Engineering | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thioredoxin (~4 Ga) | Significantly elevated thermal and acidic stability compared to modern counterparts, while maintaining chemical activity. | Demonstrates that ASR can access hyper-stable protein scaffolds from the deep past, useful for industrial processes. | [22] |

| Elongation Factor Tu (EF-Tu) & V-ATPase Subunits | Resurrected ancestors are more thermostable, consistent with a hotter ancient Earth. Stability declined over evolutionary time as Earth cooled. | Provides a historical trend where ancestral proteins can serve as better starting points for engineering in high-temperature applications. | [22] [25] |

| Hormone Receptors (~500 Ma) | ASR revealed key residues determining ligand-binding specificity, allowing engineering of receptors with novel functions. | Highlights that stable ancestral scaffolds can be used to trace and re-engineer functional evolutionary paths. | [22] |

| Ribonuclease H1 (Ec) | A model system for detailed study; shows that thermostability can be achieved through diverse, non-additive molecular mechanisms. | Illustrates the importance of characterizing dynamic properties and epistatic interactions when engineering stability. | [22] |

| Polyketide Synthase (PKS) Domains | Replacing a modern domain with a reconstructed ancestral domain improved solubility and facilitated high-resolution structural analysis by cryo-EM. | ASR is a tool for protein engineering to improve properties like solubility, aiding structural biology and mechanistic studies. | [27] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Reagents and Resources for ASR Experiments

| Reagent / Resource | Function & Role in ASR | Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Sequence Databases | Source of homologous sequences for alignment and tree-building. | UniProt, NCBI Protein Database. Crucial for broad taxonomic sampling. |

| Phylogenetic Software | Infers evolutionary relationships and reconstructs ancestral sequences. | IQ-TREE (ML), MrBayes (Bayesian), PAML/CodeML. The core computational engine of ASR. |

| Gene Synthesis Service | Provides the physical DNA for inferred ancestral sequences, which do not exist in nature. | Various commercial providers. Essential for the experimental phase. |

| Heterologous Expression System | Produces the ancestral protein for laboratory study. | E. coli, yeast, or cell-free systems. Choice depends on protein complexity and required post-translational modifications. |

| Differential Scanning Fluorimetry (DSF) | A high-throughput method to quickly estimate protein thermal stability ((T_m)). | Uses a fluorescent dye (e.g., SYPRO Orange) to monitor thermal unfolding. |

| Size Exclusion Chromatography (SEC) | Assesses the oligomeric state and purity of the ancestral protein, which can impact stability and function. | Often coupled with Multi-Angle Light Scattering (SEC-MALS) for precise molecular weight determination. |

The Critical Relationship Between Thermostability and Mutational Robustness

Frequently Asked Questions

- What is the fundamental relationship between thermostability and mutational robustness? Research indicates that selection for thermostability can lead to the emergence of mutational robustness. This is explained by plastogenetic congruence – a stable, thermostable protein structure can better tolerate mutations without compromising its fold or function, acting as a buffer against deleterious changes [28].

- Does increased thermostability always enhance a protein's evolvability? Not always. The relationship is complex. While thermostability can provide mutational robustness, excessive stability might confer conformational rigidity that hinders the structural flexibility needed to explore new functions. Evidence from bacteriophage λ shows that variants with moderately unstable host-recognition proteins were more evolvable for host-range expansion than their stabilized counterparts [29].

- What are the primary computational methods for predicting thermostability? Methods range from traditional machine learning like Support Vector Machines (SVM) and Gaussian Process Regression to more advanced deep learning models. Newer approaches, such as self-attention mechanism-driven sparse convolutional networks (SCSAddG), aim to better capture long-range dependencies in protein sequences for improved ΔΔG prediction [5]. Frameworks like GeoEvoBuilder leverage protein language models to simultaneously optimize for both activity and stability [30].

- What experimental technique is best for high-throughput thermal stability screening? High-throughput Differential Scanning Calorimetry (RS-DSC) is a powerful method. Modern platforms can simultaneously analyze up to 24 samples, providing precise melting temperatures (Tm) and enabling rapid screening of buffer conditions, protein variants, and formulations [31].

- Besides point mutations, what other strategies can improve thermostability?

Alternative strategies include:

- Hydrophobic Core Engineering: Optimizing buried hydrophobic residues to improve core packing and minimize voids [6].

- De Novo Design: Computational creation of proteins with maximized hydrogen-bond networks for extreme stability [32].

- Topological Engineering: Using techniques like protein chain threading (e.g., creating GFP catenanes) to introduce conformational constraints that enhance stability and refolding (heat回复性) [33].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Designed thermostable protein has lost catalytic activity.

- Potential Cause: Over-stabilization leading to rigidity. Excessively rigid structures can impair the conformational dynamics essential for catalytic function [29].

- Solutions:

- Employ design algorithms that consider functional dynamics, not just static stability. The GeoEvoBuilder framework, for example, is specifically reported to improve both activity and stability in a single design round [30].

- Focus stabilization efforts on regions distal from the active site to avoid interfering with the catalytic mechanism.

- Screen for stability and activity in parallel, not sequentially, to identify variants that balance both properties.

Problem: Inconsistent thermostability measurements across replicates.

- Potential Cause: Inadequate buffer standardization or protein quality. Variations in pH, ionic strength, or the presence of aggregates can significantly impact observed stability [31].

- Solutions:

- Ensure exhaustive buffer exchange into a consistent, well-defined formulation before analysis.

- Characterize protein samples for monodispersity and aggregation prior to stability assays.

- When using high-throughput DSC, leverage automated data analysis (e.g., NanoAnalyze Software) but always perform visual inspection of the thermograms to confirm automated peak detection [31].

Problem: Computational predictions of stability change (ΔΔG) do not match experimental results.

- Potential Cause: Limitations of the predictive model. Many models rely heavily on sequence or static structure and may miss context-dependent effects from long-range interactions or protein dynamics [5].

- Solutions:

- Use models that incorporate evolutionary information from protein language models (e.g., ESM2) or explicit structural dynamics simulations [30] [34].

- Validate predictions with a small-scale experimental screen to calibrate the computational tool for your specific protein family.

- Consider consensus approaches, comparing results from multiple prediction tools (e.g., FoldX, Rosetta) before committing to experimental validation.

Experimental Data & Protocols

Table 1: Quantitative Data on Thermostability Engineering from Literature

| Protein / System | Engineering Strategy | Key Metric Change | Experimental Validation Method | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bacteriophage Qβ | Experimental evolution with heat shock | Increased resistance to nitrous acid mutagenesis | Growth rate assay under mutagenesis | [28] |

| NEDD8 | Hydrophobic core optimization (2 substitutions) | ΔΔG = +1.7 kcal/mol; Tm ↑ +17°C | DSC, MD simulations, NMR, Functional assays | [6] |

| Glutathione Peroxidase 4 | AI-driven design (GeoEvoBuilder) | Catalytic efficiency ↑ 10-20x; Tm ↑ ~10°C | Enzyme kinetics, DSC, X-ray crystallography | [30] |

| Dihydrofolate Reductase | AI-driven design (GeoEvoBuilder) | Catalytic efficiency ↑ 10-20x; Tm ↑ ~10°C | Enzyme kinetics, DSC | [30] |

| Green Fluorescent Protein (GFP) | Topological catenation | Greatly improved thermal refolding (热回复性) | Fluorescence recovery after heating | [33] |

| Superstable de novo protein | Maximized H-bond network in β-sheets | Unfolding force >1000 pN (400% stronger than titin) | Steered Molecular Dynamics (SMD), retained structure at 150°C | [32] |

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Key Feature |

|---|---|---|

| TA Instruments RS-DSC | High-throughput thermal stability screening | Simultaneously analyzes up to 24 samples; automated Tm detection [31] |

| SCSAddG Model | Predicting protein thermostability trends (ΔΔG) | Self-attention & sparse convolution to capture long-range sequence dependencies [5] |

| GeoEvoBuilder Framework | AI-driven protein design for simultaneous activity and stability enhancement | Combines structure-based design with protein language model (ESM2) [30] |

| AlloSigMA 3 Platform | Computing allosteric signaling free energy upon mutation | Helps understand how stability changes can affect functional, long-range allosteric networks [34] |

| Hydrophobic Core Design Algorithm | Structure-guided stabilization via core repacking | Calculates ΔΔG for substitutions with longer/bulkier hydrophobic side chains [6] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: High-Throughput Thermal Stability Screening via RS-DSC

This protocol is adapted from the methodology used for screening monoclonal antibody formulations [31].

- Sample Preparation:

- Prepare protein samples in the buffer/formulation of interest. A concentration of ~20 mg/mL is typical, but the system can handle concentrations exceeding 330 mg/mL.

- Centrifuge samples to remove any particulate matter.

- Instrument Loading and Setup:

- Load 11 µL of each protein sample into individual channels of a disposable glass microfluidic chip (MFC).

- Seal the MFC with an adhesive glass coverslip.

- Place the assembled MFC into the sample side of the RS-DSC; a reusable PEEK chip is placed on the reference side. Up to 24 samples can be run simultaneously.

- Data Acquisition:

- Equilibrate the system at the initial temperature (e.g., 20°C) for 30 minutes.

- Run a temperature scan from 20°C to 100°C at a controlled rate of 1–2°C per minute.

- Data Analysis:

- Process thermograms using software (e.g., NanoAnalyze).

- Use automated features (e.g., RapidDSC algorithm) to detect the denaturation midpoint temperature (Tm) for each peak.

- Manually inspect and validate all automatically assigned Tm values and baselines.

Protocol 2: Assessing Mutational Robustness in Viral Populations

This protocol is based on the experimental approach used to study bacteriophage Qβ [28].

- Generate Thermostable Populations:

- Subject viral populations (e.g., RNA bacteriophage Qβ) to serial passages interspersed with heat shocks (e.g., 45-55°C). This selects for mutations conferring thermostability.

- Sequence Genomes:

- Isolate and sequence the genomes of thermostable evolved lineages to identify stabilizing mutations.

- Challenge with Mutagen:

- Passage both the thermostable evolved lines and the ancestral control lines in the presence of a chemical mutagen, such as nitrous acid.

- The mutagen increases the mutation rate, accelerating the accumulation of deleterious mutations.

- Measure Robustness:

- Measure the growth rate (or plaque-forming ability) of the populations before and after mutagenic challenge.

- Interpretation: A population with high mutational robustness will show little to no reduction in growth rate after mutagenesis, as its essential functions are buffered against the deleterious effects of mutations. Control populations will show a significant decline in fitness.

Signaling Pathways and Workflows

Diagram 1: The Thermostability-Robustness Pathway. This diagram illustrates the proposed pathway through which selection for thermostability can lead to increased mutational robustness and evolvability, while also highlighting the potential trade-off with functional dynamics.

Diagram 2: The Protein Thermostability Engineering Cycle. This workflow depicts the iterative cycle of computational design and experimental validation that is central to modern protein engineering, highlighting the critical feedback loop for refining AI models.

Modern Toolkit for Stability Engineering: From Rational Design to AI-Powered Prediction

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide: Troubleshooting Engineered Protein Thermostability

Problem: Introduced Mutation Decreases Protein Activity or Expression

| Observation | Potential Cause | Solution / Diagnostic Experiment |

|---|---|---|

| Low catalytic activity despite improved thermostability | Rigidification compromises essential conformational flexibility for catalysis [35] [36] | 1. Perform B-factor or MD simulation analysis on the mutant model to assess over-rigidification [36].2. Introduce flexibility at a distal site to compensate [36]. |

| Poor protein expression or aggregation | Destabilizing mutation disrupting protein fold or core packing [35] | 1. Use computational tools (e.g., Rosetta) pre-design to calculate folding free energy change (ΔΔG) and favor stabilizing mutations (ΔΔG < 0) [36].2. Screen for soluble expression in a smaller, representative protein domain. |

| No improvement in thermostability | Mutation location is not a key stability "hotspot" [36] | 1. Target flexible loops with high B-factors, especially those near active sites or dimer interfaces [36].2. Combine thermostability strategies (e.g., a salt bridge with a proline substitution) [36]. |

Problem: Inconsistent Measurement of Thermostability Parameters

| Observation | Potential Cause | Solution / Diagnostic Experiment |

|---|---|---|

| High variability in melting temperature (Tm) measurements | Protein aggregation during thermal denaturation, leading to irreversible unfolding [35] | 1. Include stabilizing ligands or cofactors in the buffer [36].2. Use a method that detects first-order unfolding, or switch to an activity-based half-life (t1/2) assay at elevated temperatures [36]. |

| Discrepancy between Tm and half-life (t1/2) at lower temperatures | Stability at extreme heat (Tm) does not always correlate with long-term operational stability [36] | 1. For industrial applications, prioritize measuring the functional half-life (t1/2) at your target process temperature [36].2. Use a combination of DSC (for Tm) and activity assays over time (for t1/2). |

Guide: Troubleshooting Computational Design Strategies

Problem: Low Success Rate of Predicted Stabilizing Mutations

| Observation | Potential Cause | Solution / Diagnostic Experiment |

|---|---|---|

| Computational tool (e.g., Rosetta) predicts stability but experimental validation fails | Inaccurate energy functions or lack of explicit solvent in the model [36] | 1. Use the computational prediction as a filter, not a final selector. Experimentally test the top ~10-20 candidates [36].2. Employ a consensus strategy by comparing with homologous thermophilic sequences to guide and validate design [36]. |

| Designed salt bridge is not formed | Lack of precise geometry and side-chain flexibility in the designed orientation [35] | 1. Use MD simulations to validate the stability of the salt bridge geometry in the folded state.2. Design hydrogen-bonding networks to support the salt bridge and maintain correct side-chain rotamers. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the most reliable strategies for rationally engineering a salt bridge? The most reliable strategy involves targeting sites where charged residues are already present or can be introduced with minimal backbone strain. Prioritize positions where:

- The side chains of the two charged residues (e.g., Lys/Asp, Arg/Glu) are within 4 Å in the folded structure.

- The mutation is on a surface-exposed, rigid secondary structure element to minimize entropy cost.

- You can introduce a pair of mutations simultaneously to maintain the overall protein charge, which can improve expression and solubility [35]. Computational design with tools like Rosetta can help evaluate the geometry and energy of the proposed salt bridge [36].

Q2: When should I introduce a proline residue to enhance thermostability? Proline is most effective when introduced in the first or second position of a protein loop or a turn, where it can restrict the backbone dihedral angles and reduce the entropy of the unfolded state [35] [36]. Avoid introducing proline in the middle of flexible, catalytically essential loops, as this can impair function. A "back-to-consensus" approach, where you mutate a residue to one more commonly found in thermophilic homologs, is a powerful guide for identifying beneficial proline substitutions [36].

Q3: How do I identify the best flexible loops to target for rigidification? Combine structural and sequence analysis:

- Structural Analysis: Calculate the B-factor from X-ray crystallography data or perform Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations to identify highly flexible loops. Prioritize loops that are surface-exposed but not directly involved in catalysis [36].

- Sequence Analysis: Look for loops with low sequence conservation among homologs, as this indicates natural tolerance for mutation. The "consensus" approach can again be used here to identify stabilizing mutations from thermophilic family members [36].

Q4: Why did my thermostable variant show a significant decrease in specific activity? This is a classic stability-activity trade-off. Catalysis often requires a degree of local flexibility, particularly in loops surrounding the active site. If your rigidifying mutation (e.g., in a loop) restricts a necessary conformational change for substrate binding or product release, activity will drop [35] [36]. To mitigate this, focus stabilization efforts on flexible regions that are not critical for the catalytic cycle, or use directed evolution after initial rational design to re-optimize activity.

Q5: What quantitative metrics should I use to report improved thermostability? A comprehensive assessment includes both thermodynamic and functional metrics:

- Melting Temperature (Tm): The temperature at which 50% of the protein is unfolded. An increase of 5°C or more is generally considered significant [36].

- Half-life (t1/2) at a target temperature: The time it takes for the enzyme to lose 50% of its activity at a specific, elevated temperature. A 2 to 3-fold improvement is a strong result [36].

- Specific Activity at Elevated Temperature: The enzyme's turnover number at a temperature above the mesophilic optimum. This demonstrates retained functionality under more industrially relevant conditions [36].

Data Presentation

| Strategy | Mechanism | Target Sites | Expected Outcome | Success Rate / Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Salt Bridge Engineering | Introduces electrostatic interactions (e.g., Lys-Glu) that stabilize the native fold [35]. | Surface-exposed regions, ends of alpha-helices [35]. | Increased Tm; stability against chaotropic agents [35]. | Higher success when introducing charge-neutral pairs. Can be combined with other strategies [36]. |

| Proline Substitution | Reduces the entropy of the unfolded state by restricting backbone conformation in loops and turns [35] [36]. | First position of loops, sites with high native flexibility [36]. | Improved half-life (t1/2) at elevated temperatures [36]. | "Back-to-consensus" is an effective guiding method [36]. |

| Loop Rigidification | Reduces flexibility in potential unfolding initiation sites, slowing the denaturation process [36]. | Surface loops with high B-factors, identified via MD or consensus analysis [36]. | Increased Tagg and Tm; reduced aggregation [36]. | Success rate can be ~65% with computational pre-screening (e.g., Rosetta) [36]. Avoid catalytic loops. |

| Hydrophobic Core Packing | Increases internal hydrophobicity and van der Waals contacts, improving packing efficiency [35]. | Buried sites in the protein core. | Increased overall structural rigidity and Tm [35]. | Higher frequency of Ile, Val, Leu, Phe, and Trp in thermophiles (IVYWREL index) [35]. |

Experimental Metrics from Successful Engineering Study

The table below summarizes key experimental results from the thermostability engineering of E. coli Transketolase, demonstrating the impact of strategic loop rigidification [36].

| Variant | Mutation Type | Half-life at 60°C (min) | Specific Activity at 65°C (U/mg) | Tm (°C) | kcat (s-1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild Type | - | ~15 | Baseline (1x) | 60.0 | Baseline (1x) |

| I189H | Single (Loop) | - | - | - | - |

| A282P | Single (Loop) | - | - | - | - |

| H192P / A282P | Double (Loop) | ~45 (3x) | ~5x Improved | 65.0 (+5.0) | 1.3x Improved |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: B-Factor Analysis for Identifying Flexible Loops

Purpose: To identify flexible regions in a protein structure using atomic displacement parameters (B-factors) from X-ray crystallography data for targeted rigidification [36].

Materials:

- Protein Data Bank (PDB) file of the target protein.

- Molecular visualization software (e.g., PyMOL).

- B-FITTER program or equivalent script for calculating average residue B-factors [36].

Method:

- Obtain Structure: Download the high-resolution crystal structure (PDB file) of your target protein.

- Calculate B-Factors: Use the B-FITTER tool or a custom script to compute the average B-factor for each amino acid residue in the structure.

- Define Loops: Annotate the secondary structure elements and define the loop regions connecting them using PyMOL.

- Identify Hotspots: For each loop, calculate the average B-factor by summing the B-factors of all residues within the loop and dividing by the number of residues. Flag loops with the highest average B-factors as potential targets for engineering.

- Contextual Analysis: Cross-reference high-B-factor loops with functional data (e.g., active site proximity) to avoid disrupting catalysis.

Protocol: Computational Design of Stabilizing Point Mutations using Rosetta

Purpose: To predict point mutations that improve protein stability by calculating the change in folding free energy (ΔΔG) [36].

Materials:

- High-resolution protein structure (PDB format).

- Rosetta software suite installed on a computing cluster or server.

- List of target residues for mutation (e.g., from B-factor analysis).

Method:

- Prepare Structure: Clean the PDB file by removing heteroatoms (except essential cofactors/ligands) and adding missing hydrogen atoms using Rosetta's

prepare_pdb.pyscript. - Generate Mutants: Use the

Rosetta ddg_monomerapplication. Create a list of mutation commands (e.g.,-resfile my_resfile.txt) specifying which residues to mutate and to what amino acids. - Run Calculation: Execute the Rosetta ΔΔG protocol. This typically involves:

- Backbone minimization of the wild-type and mutant structures.

- Side-chain repacking around the mutation site.

- Scoring the energy of the folded and unfolded states to compute ΔΔG.

- Analyze Output: Rosetta will output a file with predicted ΔΔG values for each mutation. A negative ΔΔG value indicates a predicted stabilizing mutation. Select top candidates (e.g., ΔΔG < -1.0 Rosetta Energy Unit) for experimental testing.

Mandatory Visualization

Workflow for Rational Thermostability Engineering

Stability-Activity Trade-off in Enzyme Engineering

The Scientist's Toolkit

Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function / Application in Thermostability Engineering |

|---|---|

| Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulation Software (e.g., GROMACS) | Used to simulate atomic-level protein movements over time, identifying flexible regions (loops) that are prime targets for rigidification [36]. |

| Rosetta Software Suite | A comprehensive modeling software for computational protein design. Its ΔΔG protocol predicts the change in folding free energy for point mutations, filtering out destabilizing designs before experimental work [36]. |

| Thermophilic Protein Homologs | Sequences from thermophilic organisms serve as a "natural library" of stabilizing mutations. A "back-to-consensus" approach, mutating residues to match these homologs, is a highly effective design strategy [36]. |

| Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) | A biophysical technique used to directly measure the thermal denaturation of a protein, providing the melting temperature (Tm) and thermodynamic parameters of unfolding [36]. |

| Fast Protein Liquid Chromatography (FPLC) | Used for the purification of engineered protein variants, particularly for assessing solubility and obtaining pure samples for activity and stability assays. |

Directed Evolution and High-Throughput Screening Strategies like Hot-CoFi

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Issues in Directed Evolution Workflows

This guide addresses frequent challenges encountered during directed evolution experiments, from library transformation to screening.

Few or No Transformants

After overnight incubation following transformation, few or no colonies are observed on selective plates [37].

| Possible Cause | Recommendations for Optimization |

|---|---|

| Suboptimal Transformation Efficiency | - Avoid freeze-thaw cycles of competent cells; re-freezing lowers efficiency ~2x [37].- Thaw cells on ice and avoid vortexing [37].- For chemical transformation, ensure DNA is free of phenol, ethanol, proteins, and detergents [37].- Consider electroporation for better efficiency with low DNA amounts or library construction [37]. |

| Suboptimal DNA Quality/Quantity | - For heat shock, use ≤5 µL of ligation mixture per 50 µL of competent cells [37].- For electroporation, purify DNA from the ligation reaction prior to transformation [37].- Use appropriate DNA amounts: 1–10 ng per 50–100 µL of chemically competent cells [37]. |

| Toxic Cloned DNA/Protein | - Use a tightly regulated expression strain with minimal basal expression [37].- Consider a low-copy number plasmid [37].- Grow cells at a lower temperature (e.g., 30°C) to mitigate toxicity [37]. |

| Insufficient Cells Plated | - Recover cells in rich medium (e.g., SOC) post-transformation for ~1 hour before plating [37].- Adjust cell volume and/or dilutions during plating to obtain a desirable number of colonies (e.g., 30-300 per plate) [37]. |

Transformants with Incorrect or Truncated DNA Inserts

Analysis reveals vectors with incorrect or truncated fragments [37].

| Possible Cause | Recommendations |

|---|---|

| Unstable DNA | - Use specialized strains (e.g., Stbl2 or Stbl4) for sequences with direct repeats, tandem repeats, or retroviral sequences [37].- For lentiviral sequences, use Stbl3 cells [37].- Pick colonies from fresh plates (<4 days old) [37]. |

| DNA Mutation | - If mutations occur during propagation, pick a sufficient number of colonies for representative screening [37].- Use high-fidelity polymerase in PCR steps to reduce accidental mutations [37]. |

| Cloned Fragment Truncated | - If using restriction enzymes, ensure no additional, overlapping restriction sites exist in the fragment [37].- For seamless cloning (e.g., Gibson Assembly), consider longer overlaps or re-designing fragments [37]. |

Many Colonies with Empty Vectors (No DNA Inserts)

After selection and analysis, the vector is found to be empty [37].

| Possible Cause | Recommendations |

|---|---|

| Improper Colony Selection | - Blue/white screening: Ensure the host strain carries the lacZΔM15 marker and the vector contains the lacZ gene with the MCS [37].- Positive selection: Verify the host strain lacks resistance to the vector's lethal gene, ensuring cells with empty vectors die [37]. |

Slow Cell Growth or Low DNA Yield

It takes unusually long to grow cells in liquid media, or purified DNA yields are insufficient [37].

| Possible Cause | Recommendations |

|---|---|

| Suboptimal Growth Conditions | - If growing at 30°C instead of 37°C, extend recovery and incubation times [37].- Use a colony no older than one month to start a culture [37].- Ensure good aeration by using larger flasks and adequate shaking [37]. |

| Wrong Media | - To increase plasmid yields, especially for pUC-based plasmids, use TB medium instead of LB [37]. |

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Core Directed Evolution Workflow

Directed evolution mimics natural selection through iterative rounds of diversification, selection, and amplification to steer proteins toward a user-defined goal [38] [39].

Structure-Guided Engineering for Thermostability

A structure-guided approach can enhance thermostability by optimizing the hydrophobic core, minimizing internal voids, and improving packing [6].

Detailed Methodology [6]:

Algorithmic Analysis:

- Input the protein's three-dimensional structure.

- Identify buried hydrophobic residues suitable for mutation, excluding functionally important residues and contact networks.

- For each candidate residue, calculate the change in free energy of unfolding (ΔΔG) for substitutions with longer or bulkier hydrophobic side chains (e.g., Val → Leu, Ile → Phe).

- Select only configurations predicted to be significantly stabilizing.

Experimental Validation:

- Construct Generation: Synthesize genes encoding the selected top-prediction variants using site-directed mutagenesis.

- Expression and Purification: Express the variant proteins (e.g., in E. coli) and purify them using standard chromatography techniques.

- Thermostability Assay:

- Use Differential Scanning Fluorimetry (DSF) or Circular Dichroism (CD) spectroscopy to determine the melting temperature (Tm).

- Compare the Tm of the variant to the wild-type protein. An increase in Tm indicates improved thermostability.

- Functional Assay:

- Perform functional assays (e.g., enzyme activity assays, binding assays) to confirm that the stabilizing mutations do not compromise the protein's native function.

- Structural Analysis (Optional):

- Use techniques like NMR spectroscopy or X-ray crystallography to validate the structural changes, such as reduced conformational fluctuations and increased stabilizing interactions.

AI-Assisted Thermostability Prediction (SCSAddG Model)

Machine learning models can predict thermostability trends, reducing the experimental screening burden [5].

Detailed Methodology for SCSAddG [5]:

Data Preparation:

- Utilize a curated dataset, such as S2648 from the ProTherm database, which contains ΔΔG values for thousands of single-point mutations.

- Preprocess the data, splitting it into training and test sets (e.g., 80/20 split).

Protein Representation (Feature Engineering):

- Encode the protein sequence by considering the physicochemical properties of the original and mutant amino acids, such as hydrophobicity, volume, and chemical characteristics.

- This creates a numerical feature vector representing each mutation.

Model Training:

- The SCSAddG model employs a Sparse Convolutional Network driven by a Self-Attention Mechanism.

- Sparse Convolution: Uses flexible convolutional kernels to extract local sequence features efficiently.

- Self-Attention Mechanism: Weights the importance of different amino acid positions, capturing long-range dependencies within the protein sequence that are critical for stability.

- The model is trained to predict the ΔΔG value (stability change) from the input feature vector.

Prediction and Validation:

- Input novel mutation data into the trained model to receive a predicted ΔΔG.

- Experimentally validate the top-predicted stabilizing mutations using the methods described in Section 2.2.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the key advantages of directed evolution over rational protein design? Directed evolution does not require in-depth knowledge of the protein's structure or catalytic mechanism, which can be difficult to predict. It is particularly powerful for optimizing properties like thermostability and catalytic activity at positions distant from the active site, where functional linkages are complex and unknown [38] [40].

Q2: What is the main limitation of directed evolution? The primary bottleneck is often the requirement for a robust high-throughput screening or selection assay to evaluate large libraries of variants. Developing such assays can be time-consuming and is often highly specific to a particular activity, making it non-transferable [38].

Q3: How can I improve the stability of a protein that is toxic to the host cells?

- Use a tightly regulated expression strain to minimize basal (leaky) expression of the toxic gene [37].

- Clone the gene into a low-copy-number plasmid to reduce the gene dosage [37].

- Lower the growth temperature (e.g., to 30°C or room temperature) to reduce the metabolic burden and mitigate toxicity [37].

Q4: What can I do if my transformation efficiency is low?