Deep Learning for Protein Representation Encoding: From Sequence to Structure in Computational Biology

Protein representation learning (PRL) has emerged as a transformative force in computational biology, enabling data-driven insights into protein structure and function.

Deep Learning for Protein Representation Encoding: From Sequence to Structure in Computational Biology

Abstract

Protein representation learning (PRL) has emerged as a transformative force in computational biology, enabling data-driven insights into protein structure and function. This article provides a comprehensive overview for researchers and drug development professionals, exploring how deep learning techniques encode protein data—from sequences and 3D structures to evolutionary patterns—into powerful computational representations. We examine foundational concepts, diverse methodological approaches including topological and multimodal learning, and address key challenges like data scarcity and model interpretability. Through validation across tasks like mutation effect prediction and drug discovery, we demonstrate how these representations are revolutionizing protein engineering and therapeutic development, while outlining future directions for the field.

The Protein Representation Learning Landscape: From Amino Acids to 3D Structures

The Sequence-Structure-Function Paradigm in Computational Biology

The sequence-structure-function paradigm has long served as a foundational framework in structural biology, positing that a protein's amino acid sequence determines its three-dimensional structure, which in turn dictates its biological function. While this paradigm has guided research for decades, recent advances in deep learning and artificial intelligence are fundamentally transforming how we extract functional insights from sequence data. This technical review examines the current state of computational methods that leverage this paradigm, with particular focus on deep learning approaches for protein representation encoding. We explore how modern algorithms—including protein language models, geometric neural networks, and multi-modal architectures—are overcoming traditional limitations to enable accurate function prediction even for proteins with no evolutionary relatives. The integration of biophysical principles with data-driven approaches represents a significant shift toward more powerful, generalizable models capable of illuminating the vast unexplored regions of protein space.

The classical sequence-structure-function paradigm represents a central dogma in structural biology: protein sequence dictates folding into a specific three-dimensional structure, and this structure enables biological function [1]. For decades, this principle has guided both experimental and computational approaches to protein function annotation. However, this straightforward relationship has been challenged by the discovery of proteins with similar sequences adopting different functions, and conversely, proteins with divergent sequences converging on similar functions and structures [1].

The paradigm is undergoing substantial evolution driven by two key developments. First, large-scale structure prediction initiatives have revealed that the protein structural space appears continuous and largely saturated [1], suggesting we have sampled much of the possible structural universe. Second, the application of deep learning has revolutionized our ability to model complex sequence-structure-function relationships without explicit reliance on homology or manual feature engineering [2] [3].

Within the context of protein representation encoding research, this evolution marks a shift from handcrafted features to learned representations that capture intricate biological patterns [4]. Modern representation learning approaches now capture not just evolutionary constraints but also biophysical principles governing protein folding, stability, and interactions [5]. This review examines how these advanced encoding strategies are breathing new life into the sequence-structure-function paradigm, enabling unprecedented accuracy in predicting protein function across diverse biological contexts.

Data Modalities and Representation Strategies

Protein data encompasses multiple hierarchical levels of information, each requiring specialized encoding strategies for computational analysis. The integration of these modalities enables comprehensive functional annotation.

Table 1: Fundamental Protein Data Modalities and Their Characteristics

| Modality | Description | Encoding Strategies | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sequence | Linear amino acid sequence | One-hot encoding, BLOSUM, embeddings from PLMs (ESM, ProtTrans) | Function annotation, mutation effect prediction, remote homology detection |

| Structure | 3D atomic coordinates | Geometric Vector Perceptrons, Graph Neural Networks, 3D Zernike descriptors | Ligand binding prediction, interaction site identification, stability engineering |

| Evolution | Conservation patterns from MSAs | Position-Specific Scoring Matrices, covariance analysis | Functional site detection, contact prediction, evolutionary relationship inference |

| Biophysical | Energetic and dynamic properties | Molecular dynamics features, Rosetta energy terms, surface properties | Protein engineering, stability optimization, functional mechanism elucidation |

Sequence-Based Representations

Sequence representations form the foundation of most deep learning approaches in computational biology. Fixed representations include one-hot encoding and substitution matrices like BLOSUM, which embed biochemical similarities between amino acids [4]. Learned representations from protein language models (PLMs) such as ESM (Evolutionary Scale Modeling) and ProtTrans have demonstrated remarkable capability in capturing structural and functional information directly from sequences [2] [6]. These transformer-based models, pre-trained on millions of natural protein sequences, generate context-aware embeddings that encode semantic relationships between amino acids, analogous to how natural language processing models capture word meanings [2].

Structure-Based Representations

Structural representations encode the three-dimensional arrangement of atoms in proteins, providing critical information about functional mechanisms. Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) represent proteins as graphs with nodes as atoms or residues and edges as spatial relationships, effectively capturing local environments and long-range interactions [3]. Geometric Vector Perceptrons and SE(3)-equivariant networks incorporate rotational and translational symmetries inherent in structural data, enabling robust performance across different molecular orientations [2]. For local binding site comparison, 3D Zernike descriptors (3DZD) provide rotation-invariant representations of pocket shape and physicochemical properties, facilitating rapid comparison of functional sites without structural alignment [7].

Integrated and Multi-Modal Representations

The most powerful modern approaches integrate multiple representation types. Multi-modal architectures combine sequence, structure, and evolutionary information to capture complementary aspects of protein function [2] [8]. For example, the PortalCG framework employs 3D ligand binding site-enhanced sequence pre-training to encode evolutionary links between functionally important regions across gene families [8]. Similarly, mutational effect transfer learning (METL) unites molecular simulations with sequence representations to create biophysically-grounded models that generalize well even with limited experimental data [5].

Computational Methodologies and Architectures

Core Deep Learning Architectures

Table 2: Deep Learning Architectures for Protein Function Prediction

| Architecture | Key Variants | Strengths | Protein-Specific Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Graph Neural Networks | GCN, GAT, GraphSAGE, GAE | Captures spatial relationships, handles irregular structure | PPI prediction, binding site identification, structure-based function annotation |

| Transformers | ESM, ProtTrans, METL | Models long-range dependencies, transfer learning capability | Sequence-based function prediction, zero-shot mutation effects, remote homology |

| Convolutional Networks | 1D-CNN, 3D-CNN | Local pattern detection, parameter efficiency | Sequence motif discovery, structural motif recognition, contact maps |

| Equivariant Networks | SE(3)-Transformers | Preserves geometric symmetries, robust to rotations | Structure-based virtual screening, docking pose prediction, dynamics modeling |

Several specialized architectures have been developed to address protein-specific challenges. Attention-based GNNs enable models to focus on functionally important residues during protein-protein interaction prediction [3]. Geometric Vector Perceptrons jointly model scalar and vector features to maintain geometric integrity in structural representations [2]. The METL framework incorporates biophysical knowledge through pre-training on molecular simulation data before fine-tuning on experimental measurements, enhancing performance in low-data regimes [5].

Learning Strategies and Paradigms

Beyond architectural innovations, strategic training approaches significantly enhance model performance:

- Self-supervised pre-training: Models like ESM learn general protein representations through masked token prediction on large unlabeled sequence databases, capturing fundamental principles of protein structure and function [2].

- Multi-task learning: Simultaneous training on related tasks (e.g., stability, activity, expression) encourages representations that generalize across functional dimensions [3].

- Meta-learning: Approaches like PortalCG's out-of-cluster meta-learning extract transferable knowledge from diverse gene families, enabling application to dark proteins with no known relatives [8].

- Energy-based models: These learn the underlying fitness landscape of proteins, facilitating design of functional sequences with desired properties [2].

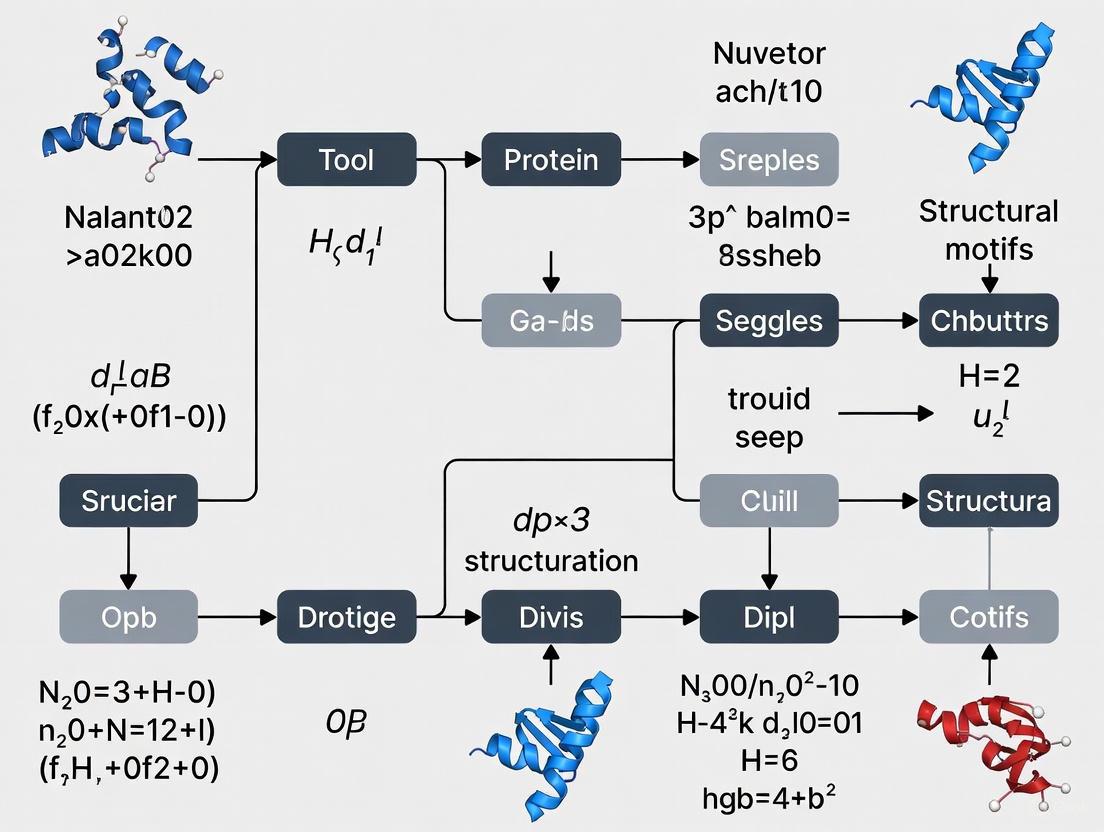

PortalCG Meta-Learning Framework

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol: METL Framework for Biophysics-Informed Function Prediction

The METL (Mutational Effect Transfer Learning) framework exemplifies the integration of biophysical principles with deep learning for protein engineering applications [5]:

Synthetic Data Generation

- Select base protein(s) of interest (single protein for METL-Local or 148 diverse proteins for METL-Global)

- Generate 20 million sequence variants with up to 5 random amino acid substitutions using Rosetta

- Model variant structures using Rosetta's comparative modeling protocol

- Compute 55 biophysical attributes for each variant (molecular surface areas, solvation energies, van der Waals interactions, hydrogen bonding)

Model Pre-training

- Initialize transformer encoder with structure-based relative positional embeddings

- Train model to predict biophysical attributes from sequence variants

- Use mean squared error loss between predicted and Rosetta-computed attributes

- Validate pre-training with Spearman correlation (target: >0.85 for METL-Local)

Experimental Fine-tuning

- Acquire experimental sequence-function data (e.g., fluorescence, stability, activity measurements)

- Replace attribute prediction head with property-specific regression/classification head

- Fine-tune entire model on experimental data with appropriate loss function

- Employ rigorous train/validation/test splits with size variations (64-1000+ examples)

Validation and Deployment

- Evaluate on extrapolation tasks: mutation, position, regime, and score extrapolation

- Compare against baselines (Rosetta total score, ESM fine-tuned, EVE, ProteinNPT)

- Deploy for protein design with iterative experimental validation

Protocol: Structure-Based Function Prediction with Local Descriptors

For predicting function from structure without global homology, local methods like Pocket-Surfer and Patch-Surfer provide robust solutions [7]:

Structure Preprocessing

- Generate protein surface using Adaptive Poisson-Boltzmann Solver (APBS)

- Identify potential binding pockets using VisGrid or LIGSITE

- Define pocket surface by casting rays from predicted pocket centers

Local Representation Generation

- Pocket-Surfer: Encode entire pocket shape and electrostatic potential using 3D Zernike descriptors

- Patch-Surfer: Segment pocket surface into overlapping 5Å radius patches

- Compute 3DZDs for shape, electrostatic potential, and hydrophobicity of each patch

Database Comparison

- Calculate Euclidean distances between query and database pocket descriptors

- For Patch-Surfer, employ modified bipartite matching to identify similar patch pairs

- Compute pocket similarity as weighted combination of patch similarities

Function Transfer

- Rank database matches by similarity score

- Transfer function from top matches with similar binding pockets

- Validate predictions through experimental testing or independent computational verification

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Computational Resources for Protein Function Prediction

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Databases | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protein Databases | UniProt, PDB, AlphaFold DB | Source sequences and structures | Training data, homology searching, functional annotation |

| Interaction Databases | STRING, BioGRID, IntAct | Protein-protein interactions | PPI prediction validation, network biology |

| Function Annotations | Gene Ontology, KEGG, CATH | Functional and structural classification | Model training, prediction interpretation |

| Structure Prediction | AlphaFold2, Rosetta, ESMFold | 3D structure from sequence | Input for structure-based methods, feature generation |

| Specialized Software | DeepFRI, PortalCG, METL | Function prediction implementations | Benchmarking, specialized prediction tasks |

| Molecular Simulation | Rosetta, GROMACS, OpenMM | Biophysical property calculation | Generating training data, mechanistic insights |

Current Challenges and Research Frontiers

Despite significant progress, several challenges remain in fully realizing the sequence-structure-function paradigm through deep learning:

Data Limitations and Biases

The available protein data exhibits substantial biases that limit model generalizability. Structural databases are dominated by easily crystallized proteins, while function annotations concentrate on well-studied biological processes [1]. The MIP database of microbial protein structures helps address this by focusing on archaeal and bacterial proteins, revealing 148 novel folds not present in existing databases [1]. However, massive regions of protein space remain underexplored, particularly for proteins with high disorder or complex quaternary structures.

The Out-of-Distribution Problem

Most function prediction methods perform well on proteins similar to their training data but struggle with dark proteins that have no close evolutionary relatives [8]. PortalCG addresses this through meta-learning that accumulates knowledge from diverse gene families and applies it to novel families, significantly outperforming conventional machine learning and docking approaches for understudied proteins [8].

Integrating Dynamics and Allostery

The static structure perspective fails to capture functional mechanisms dependent on protein dynamics and allosteric regulation [9]. Molecular dynamics simulations can provide these insights but remain computationally prohibitive at scale. New approaches that learn from MD trajectories or directly predict dynamic properties from sequence are emerging as critical research directions [4] [9].

METL Biophysics Integration Workflow

The sequence-structure-function paradigm continues to evolve through integration with deep learning methodologies. Several promising research directions are emerging:

Integrated Multi-Scale Modeling

Future approaches will likely combine atomistic detail with cellular context, modeling how protein function emerges from molecular interactions within biological pathways [2] [8]. This requires integrating function prediction with protein interaction networks and metabolic pathways to move from isolated molecular functions to systems-level understanding.

Explainable AI for Biological Insight

As models become more complex, developing interpretation methods is crucial for extracting biological insights beyond mere prediction [6]. Sparse autoencoders applied to protein language models are beginning to reveal what features these models use for predictions, potentially leading to novel biological discoveries [6].

Generative Models for Protein Design

The sequence-structure-function paradigm is increasingly being inverted for protein design, where desired functions inform the generation of novel sequences and structures [10] [5]. Models like METL demonstrate the potential of biophysics-aware generation, successfully designing functional GFP variants with minimal training examples [5].

In conclusion, the integration of deep learning with the sequence-structure-function paradigm has transformed computational biology from a homology-dependent endeavor to a principles-driven discipline. By learning representations that capture evolutionary, structural, and biophysical constraints, modern algorithms can predict protein function with increasing accuracy and generalizability. As these methods continue to mature, they promise to illuminate the vast unexplored regions of protein space, accelerating drug discovery and fundamental biological understanding.

The accurate computational representation of proteins is a foundational challenge in bioinformatics, with profound implications for drug discovery, protein engineering, and understanding fundamental biological processes. The evolution of protein encoding methodologies mirrors advances in machine learning, transitioning from expert-designed features to sophisticated deep learning models that automatically extract meaningful patterns from raw sequence and structure data. This paradigm shift is framed within a broader research thesis: that effective protein representation encoding is the cornerstone for accurate function prediction, engineering, and understanding.

Early methods relied on handcrafted features such as one-hot encoding, k-mer counts, and physiochemical properties [11]. While interpretable, these representations often failed to capture the complex semantic and structural constraints governing protein function. The contemporary deep learning era leverages unsupervised pre-training on massive sequence databases, geometric deep learning for structural data, and multi-modal integration to create representations that profoundly advance our ability to predict and design protein behavior [2] [12].

The Handcrafted Feature Era: Foundations and Limitations

Initial approaches to protein representation were built on features derived from domain knowledge and simple sequence statistics.

Primary Feature Types

- Amino Acid Composition and One-Hot Encoding: This simplest representation treats each amino acid in a sequence as an independent, categorical variable, typically using a 20-dimensional binary vector where each dimension corresponds to one of the standard amino acids. It completely ignores the context and order of residues [11].

- k-mer Counts: This method breaks down the protein sequence into overlapping subsequences of length k (e.g., 3-mers, 4-mers, 5-mers). The frequency of these k-mers is used to create a fixed-length vector representation for the entire protein, capturing local sequence order but at the cost of high dimensionality [11].

- Physicochemical Property Encoding: Experts manually designed features based on known amino acid properties, such as hydrophobicity, charge, polarity, and size. These representations embedded biochemical intuition but were inherently limited by the completeness of human knowledge [2].

Performance and Constraints

These handcrafted features formed the basis for early machine learning classifiers. However, their performance was limited. Studies found that models using these features were outperformed by simple sequence alignment methods like BLASTp in function prediction tasks [13]. A critical limitation was their inability to capture long-range interactions and complex hierarchical patterns that define protein structure and function [11] [2].

Table 1: Comparison of Traditional Handcrafted Feature Encoding Methods

| Method | Core Principle | Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| One-Hot Encoding | Independent binary representation for each of the 20 amino acids. | Simple, interpretable, no prior biological knowledge required. | Ignores context and semantic meaning; very high-dimensional for long sequences. |

| k-mer Counts | Frequency of all possible contiguous subsequences of length k. | Captures local order and short-range motifs. | Loses global sequence information; feature vectors become extremely sparse for large k. |

| Physicochemical Properties | Encoding residues based on expert-defined biochemical features (e.g., hydrophobicity). | Incorporates domain knowledge; can be informative for specific tasks. | Incomplete; relies on pre-existing human knowledge which may not capture all relevant factors. |

The Deep Learning Revolution: A New Paradigm

Deep learning has transformed protein encoding by using neural networks to automatically learn informative representations directly from data, moving beyond the constraints of manual feature engineering.

Protein Language Models (pLMs)

Inspired by breakthroughs in natural language processing (NLP), pLMs treat protein sequences as "sentences" where amino acids are "words." Models like ESM2, ESM1b, and ProtBert are pre-trained on millions of protein sequences from databases like UniProt using objectives like masked language modeling [2] [13]. This self-supervised pre-training allows them to learn the underlying "grammar" of protein sequences, capturing evolutionary constraints, structural patterns, and functional semantics without explicit labels [14] [12]. These embeddings have been shown to outperform handcrafted features across a wide range of tasks, from secondary structure prediction to function annotation [11] [13].

Structure-Aware Geometric Deep Learning

While sequences are primary, function is ultimately determined by 3D structure. Geometric deep learning models explicitly represent and learn from structural data.

- Graph Neural Networks (GNNs): Protein structures are naturally represented as graphs, where residues are nodes and edges represent spatial proximity or chemical bonds. GNNs perform message-passing across this graph to learn structural contexts [15] [16]. Tools like DeepFRI and GAT-GO use GCNs (Graph Convolutional Networks) on protein contact maps to predict function [15].

- SE(3)-Equivariant Networks: These advanced architectures are designed to be equivariant to rotations and translations in 3D space, a crucial property for correctly modeling biomolecular structures. The Topotein framework uses SE(3)-equivariant message passing across a hierarchical representation of protein structure (Protein Combinatorial Complex), enabling superior capture of multi-scale structural patterns [17].

Multi-Modal and Knowledge-Enhanced Models

The most advanced models integrate multiple data types to create comprehensive representations.

- ECNet: Integrates both local evolutionary context (from homologous sequences) and global semantic context (from a protein language model) to predict functional fitness for protein engineering, effectively capturing residue-residue epistasis [14].

- DPFunc: Leverages domain information from sequences to guide the attention mechanism in learning structure-function relationships, allowing it to detect key functional residues and regions [15].

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Comparison of Deep Learning Encoding Methods on Key Tasks

| Model | Core Encoding Approach | Key Benchmark/Task | Reported Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| ESM2 (pLM) [13] | Transformer-based Protein Language Model | Enzyme Commission (EC) Number Prediction | Superior to one-hot encoding; complementary to BLASTp, especially for sequences with <25% identity. |

| Topotein (TCPNet) [17] | Topological Deep Learning; SE(3)-Equivariant GNN | Protein Fold Classification | Consistently outperforms state-of-the-art geometric GNNs, validating the importance of hierarchical features. |

| DPFunc [15] | Domain-guided Graph Attention Network | Protein Function Prediction (Gene Ontology) | Outperformed GAT-GO with Fmax increases of 16% (Molecular Function), 27% (Cellular Component), and 23% (Biological Process). |

| ECNet [14] | Evolutionary Context-integrated LSTM | Fitness Prediction on ~50 DMS datasets | Outperformed existing ML algorithms in predicting sequence-function relationships, enabling generalization to higher-order mutants. |

Experimental Protocols in the Deep Learning Era

Protocol: Large-Scale Pre-training for Protein Language Models

Objective: To learn general-purpose, contextual representations of amino acids and protein sequences from unlabeled data.

- Data Curation: Assemble a large-scale dataset of protein sequences (e.g., from UniRef or UniProt), containing millions to billions of sequences [2] [18].

- Tokenization: Convert each protein sequence into a string of one-letter amino acid codes. Some models use subword tokenization, but character-level (per residue) is most common.

- Model Architecture Selection: Typically a deep Transformer network or a Bidirectional LSTM (e.g., for ELMo-like models) [11].

- Pre-training Objective: Employ a self-supervised task. The most common is the Masked Language Modeling (MLM) objective, where a random subset (e.g., 15%) of residues in an input sequence is masked, and the model is trained to predict the masked residues based on their context [2] [12].

- Output: The pre-trained model generates a high-dimensional (e.g., 1024- or 1280-dimensional) embedding vector for each residue in a sequence, as well as a summary embedding for the entire protein (e.g., via averaging or using a special token) [11].

Protocol: Training a Structure-Based Function Prediction Model (e.g., DPFunc)

Objective: To accurately predict protein function (e.g., Gene Ontology terms) by integrating sequence and structure information under the guidance of domain knowledge [15].

- Input Data Preparation:

- Sequence & Labels: Collect protein sequences and their experimentally validated GO annotations.

- Structure Input: Use experimentally determined structures (from PDB) or high-confidence predicted structures from AlphaFold2/ESMFold.

- Domain Information: Scan protein sequences with InterProScan to identify functional domains.

- Feature Extraction:

- Residue-Level Features: Generate initial residue embeddings using a pre-trained pLM (e.g., ESM-1b).

- Structure Graph Construction: Build a graph where nodes are residues. Connect nodes with edges based on spatial proximity (e.g., Cα atoms within a cutoff distance), creating a contact map.

- Model Training:

- Residue-Level Feature Learning: Process the initial residue features and the structure graph through several Graph Convolutional Network (GCN) layers to create updated, structure-aware residue representations.

- Protein-Level Feature Learning: This is the core innovation. The detected domain entries are converted into dense vectors via an embedding layer. An attention mechanism, guided by the protein's overall domain representation, weighs the importance of each residue. A final protein-level representation is generated by a weighted sum of the residue features.

- Function Prediction: The protein-level feature vector is passed through fully connected layers to predict GO terms.

- Evaluation: Use standard metrics from the Critical Assessment of Functional Annotation (CAFA), such as Fmax (maximum F-score) and AUPR (Area Under the Precision-Recall Curve), on a held-out test set [15].

Diagram 1: DPFunc's domain-guided architecture integrates sequence, structure, and domain knowledge [15].

This table details key computational tools and data resources that are foundational for modern protein representation learning research.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for Protein Encoding

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| UniProtKB [2] | Database | A comprehensive repository of protein sequence and functional information, used for training language models and as a ground truth reference. |

| Protein Data Bank (PDB) [15] [18] | Database | The single global archive for experimentally determined 3D structures of proteins and nucleic acids, essential for training and validating structure-based models. |

| AlphaFold DB [16] [18] | Database | Provides high-accuracy predicted protein structures for nearly the entire UniProt proteome, enabling large-scale structure-based analysis where experimental structures are unavailable. |

| ESM-1b / ESM-2 [15] [13] | Pre-trained Model | State-of-the-art protein Language Models used to generate powerful, context-aware residue and protein embeddings for downstream tasks. |

| InterProScan [15] | Software Tool | Scans protein sequences against multiple databases to identify functional domains, motifs, and sites, providing critical expert knowledge for guidance. |

| ProteinWorkshop [16] | Benchmark Suite | A comprehensive benchmark for evaluating protein structure representation learning with Geometric GNNs, facilitating rigorous comparison of new methods. |

The evolution of protein encoding from handcrafted features to deep learning represents a fundamental shift in our computational approach to biology. The new paradigm leverages unsupervised learning on big data to uncover the complex rules of protein sequence-structure-function relationships. The current state-of-the-art is characterized by multi-modal architectures that seamlessly integrate sequence, evolutionary, structural, and domain knowledge [15] [14] [2].

Future research will likely focus on several key challenges:

- Improved Efficiency: Reducing the computational cost of large-scale pre-training and inference.

- Generalizability: Enhancing model performance on proteins with few or no homologs, moving beyond patterns seen in natural sequences.

- Explicit Reasoning: Developing more interpretable models that not only predict but also explain the structural and biophysical mechanisms behind their predictions.

- Generative Design: Leveraging these powerful representations for the inverse problem of designing novel proteins with desired functions from scratch [2] [12].

As these models become more accurate, efficient, and interpretable, they will increasingly serve as indispensable tools for researchers and drug developers, accelerating the pace of discovery and engineering in the life sciences.

Proteins are fundamental macromolecules that serve as the workhorses of the cell, participating in virtually every biological process. Understanding their functions is essential for advancing knowledge in fields such as drug discovery, genetic research, and disease treatment. The exponential growth of biological data has created both unprecedented opportunities and significant challenges for protein characterization. While traditional experimental methods for determining protein function are time-consuming and expensive, computational approaches—particularly deep learning—have emerged as transformative tools for bridging this knowledge gap. These advanced methods rely on distinct, interconnected types of protein data to make accurate predictions. This technical guide provides an in-depth examination of the three core data types—sequences, structures, and evolutionary information—that form the foundational inputs for deep learning models in protein representation encoding research. We will explore the methodologies for obtaining these data, their interrelationships, and their critical roles in powering the next generation of computational biology tools for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Protein Sequences: The Primary Blueprint

Composition and Significance

The protein sequence represents the most fundamental data type, comprising a specific linear order of amino acids linked by peptide bonds. This primary structure dictates how the polypeptide chain folds into its specific three-dimensional conformation, which ultimately determines the protein's function. The unique arrangement of amino acids, each with distinct chemical properties, influences folding pathways, stability, and interaction capabilities. Any alterations in this sequence, such as mutations, can lead to profound changes in structure and function, potentially resulting in various diseases or altered biological activities [19].

Experimental and Computational Sequencing Methods

Multiple methodologies have been developed to determine protein sequences, each with distinct advantages and limitations. The table below summarizes key protein sequencing techniques:

Table 1: Protein Sequencing Methods Comparison

| Method | Key Principle | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Edman Degradation | Sequential chemical removal of N-terminal amino acids | High accuracy for short sequences; Direct sequencing | Limited to ~50-60 residues; Less effective for modified proteins |

| Mass Spectrometry (MS) | Determines mass-to-charge ratio of peptides | High sensitivity; Effective for complex mixtures | Requires sophisticated data analysis; Sample preparation needed |

| Tandem MS (MS/MS) | Multiple stages of mass spectrometry for peptide fragmentation | Detailed peptide sequencing; Detects post-translational modifications | Complex data analysis; Relies on sample quality and fragmentation efficiency |

| De Novo Sequencing | Determines sequences without prior information using fragmentation patterns | Useful for novel proteins; Reveals new sequences and modifications | Requires extensive computational resources; Quality of fragmentation affects results |

| Single-Molecule Protein Sequencing | Nanopore technologies analyzing individual protein molecules | Precision for rare samples; Real-time sequencing | Technological challenges; Complex data interpretation; Specialized equipment |

Bioinformatics Tools for Sequence Analysis

Several sophisticated bioinformatics tools enable researchers to extract meaningful information from protein sequences:

- BLAST (Basic Local Alignment Search Tool): A widely used algorithm for comparing protein sequences against databases of known sequences to identify homologs, evolutionary relationships, and predict functional domains [19] [20].

- UniProt: A comprehensive protein sequence database offering detailed annotations including protein function, structure, post-translational modifications, and interactions [2].

- Pfam and InterPro: Databases of protein families and conserved domains essential for understanding functional roles and predicting protein functions based on domain composition [19] [20].

- Clustal Omega and MUSCLE: Powerful tools for multiple sequence alignment that identify conserved regions and infer evolutionary relationships by comparing sequences across different species or within protein families [19].

Protein Structures: The Three-Dimensional Reality

The Hierarchical Organization of Protein Structure

Protein structure is organized into four distinct levels, each contributing to the overall function:

- Primary Structure: The linear sequence of amino acids in a polypeptide chain, determined by the nucleotide sequence of the corresponding gene [19].

- Secondary Structure: Local folding patterns including alpha helices and beta sheets, stabilized by hydrogen bonds between backbone atoms [19]. These elements serve as building blocks for higher-order structures.

- Tertiary Structure: The three-dimensional conformation of a single polypeptide chain, formed by interactions between secondary structural elements and stabilized by hydrophobic interactions, hydrogen bonds, and disulfide bridges [19].

- Quaternary Structure: The assembly of multiple polypeptide chains (subunits) into a functional protein complex, enabling cooperative interactions and allosteric regulation [19].

Structural Classification and the Protein Structure Universe

Protein structures cluster into four major classes when mapped based on similarity among 3D structures: all-α (alpha helices), all-β (beta sheets), α+β (mixed helices and sheets), and α/β (alternating helices and sheets) [21]. This structural classification reveals important evolutionary constraints, with studies suggesting that recently emerged proteins belong mostly to three classes (α, β, and α+β), while ancient proteins evolved to include the α/β class, which has become the most dominant population in present-day organisms [21].

Experimental and Computational Structure Determination

The Protein Data Bank (PDB) serves as the central repository for experimentally determined protein structures. Traditional experimental methods include X-ray crystallography, NMR spectroscopy, and cryo-electron microscopy. Recently, deep learning has revolutionized protein structure prediction through breakthroughs like:

- AlphaFold2: Deep neural networks that predict protein 3D structures with near-experimental accuracy based solely on sequence data [2].

- AlphaFold3 and AlphaFold-Multimer: Extensions enabling predictions of protein complexes and biological macromolecular assemblies [2].

- ESMFold: A protein language model that predicts high-accuracy protein structures from sequences [15].

These advances have dramatically expanded the structural coverage of the protein universe, enabling structure-based function prediction at unprecedented scales.

Evolutionary Information: The Historical Record

Evolutionary Patterns and Conservation

Evolutionary information captures the historical constraints on protein sequences and structures across different species. The fundamental premise is that functionally important residues tend to be more conserved through evolution due to selective pressure. Analysis of evolutionary patterns provides several types of biologically relevant information:

- Sequence Conservation: Identifies residues critical for maintaining structure or function across homologous proteins.

- Coevolution: Detects pairs of residues that evolve in a correlated manner, often indicating spatial proximity or functional coordination [22].

- Phylogenetic Analysis: Reconstructs evolutionary relationships among protein families to infer functional divergence.

Methods for Extracting Evolutionary Information

Several computational approaches extract evolutionary signals from protein sequence families:

- Multiple Sequence Alignments (MSAs): Align homologous sequences to identify conserved positions and patterns [23] [20].

- Evolutionary Trace Methods: Rank residue conservation to identify functional sites [20].

- Direct Coupling Analysis (DCA): Statistical physics-based approaches to identify coevolving residue pairs [22].

- Protein Language Models: Self-supervised learning on millions of protein sequences to capture evolutionary constraints [24] [6].

Evolutionary Couplings for Structure and Interaction Prediction

Analysis of correlated evolutionary changes across proteins can identify residues that are close in space with sufficient accuracy to determine three-dimensional structures of protein complexes [22]. This approach has been successfully applied to predict protein-protein contacts in complexes of unknown structure and to distinguish between interacting and non-interacting protein pairs in large complexes [22]. The evolutionary sequence record thus serves as a rich source of information about protein interactions complementary to experimental methods.

Integrating Data Types for Function Prediction

The Relationship Between Data Types

The three protein data types form an interconnected hierarchy of information. The sequence dictates the possible structural conformations through biophysical constraints. The structure, in turn, determines molecular function by creating specific binding sites and catalytic surfaces. Evolutionary information provides the historical context of these relationships, highlighting which elements are functionally constrained across biological diversity. Deep learning models excel at integrating these complementary data types to achieve performance superior to methods relying on any single data type.

Deep Learning Architectures for Multimodal Integration

Advanced deep learning approaches have been developed to leverage multiple protein data types:

- DPFunc: A deep learning-based method that integrates domain-guided structure information for accurate protein function prediction. It leverages domain information within protein sequences to guide the model toward learning the functional relevance of amino acids in their corresponding structures [15].

- DeepFRI and GAT-GO: Graph neural network-based methods that use protein structures represented as contact maps to extract features for function prediction [15].

- Multimodal Transformers: Architectures that process sequence, structure, and evolutionary information simultaneously through attention mechanisms [2] [15].

Table 2: Protein Data Types in Deep Learning Applications

| Data Type | Key Features | Deep Learning Approaches | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sequence | Amino acid residues, domain motifs, physicochemical properties | Transformers (ESM, ProtTrans), CNNs, LSTMs | Function annotation, mutation effects, remote homology detection |

| Structure | 3D coordinates, contact maps, surface topography | GNNs, SE(3)-equivariant networks, 3D CNNs | Binding site prediction, protein design, function annotation |

| Evolutionary Information | MSAs, conservation scores, coevolution patterns | Protein language models, attention mechanisms | Functional site detection, interaction prediction, stability effects |

Experimental Validation of Functional Predictions

Validating computational predictions is essential for establishing biological relevance. A machine learning method that combines statistical models for protein sequences with biophysical models of stability can predict functional sites by analyzing multiplexed experimental data on variant effects [23]. This approach successfully identifies active sites, regulatory sites, and binding sites by distinguishing between residues important for structural stability versus those directly involved in function.

The following workflow diagram illustrates the experimental and computational pipeline for identifying functionally important sites in proteins:

Diagram 1: Functional Site Identification Workflow

Key Databases and Computational Tools

Researchers in protein science and computational biology rely on a curated set of databases and tools for accessing and analyzing protein data:

Table 3: Essential Research Resources for Protein Data Analysis

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function | URL/Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| UniProt | Database | Comprehensive protein sequence and functional annotation | https://www.uniprot.org/ [2] [19] |

| Protein Data Bank (PDB) | Database | Experimental 3D structures of proteins and complexes | https://www.rcsb.org/ [3] |

| Pfam | Database | Protein family domains and multiple sequence alignments | http://pfam.sanger.ac.uk [19] [20] |

| InterPro | Database | Integrated resource for protein domain classification | https://www.ebi.ac.uk/interpro [19] [20] |

| AlphaFold DB | Database | Predicted protein structures from AlphaFold | https://alphafold.ebi.ac.uk/ [2] [15] |

| STRING | Database | Known and predicted protein-protein interactions | https://string-db.org/ [3] |

| ESM | Tool | Protein language model for sequence representation | [2] [6] |

| InterProScan | Tool | Protein sequence analysis and domain detection | [15] |

| Rosetta | Tool | Protein structure prediction and design suite | [23] |

| EVcouplings | Tool | Evolutionary coupling analysis for contact prediction | [22] |

Implementation Framework for Deep Learning in Protein Research

The following diagram illustrates the architecture of DPFunc, a state-of-the-art deep learning framework that integrates multiple protein data types for function prediction:

Diagram 2: DPFunc Architecture for Protein Function Prediction

The integration of protein sequences, structures, and evolutionary information represents the cornerstone of modern computational biology research. As deep learning continues to revolutionize protein science, the synergistic use of these complementary data types enables increasingly accurate predictions of protein function, interactions, and biophysical properties. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, understanding the strengths, limitations, and interrelationships of these fundamental data types is essential for designing robust computational experiments and interpreting their results. The ongoing development of multimodal deep learning architectures that seamlessly integrate sequence, structural, and evolutionary information promises to further accelerate our understanding of protein function and its applications in therapeutic development and biotechnology.

Deep learning has revolutionized the field of bioinformatics, particularly in protein representation encoding, by providing powerful tools to decipher the complex relationship between amino acid sequences, three-dimensional structures, and biological function. The selection of an appropriate representation approach is a fundamental determinant of model performance in protein prediction tasks [25]. As the volume of available protein data continues to grow, three major learning paradigms have emerged: feature-based, sequence-based, and structure-based approaches. Each paradigm offers distinct advantages in capturing different aspects of protein information, from evolutionary patterns to structural constraints and functional determinants.

This technical guide provides an in-depth analysis of these core paradigms, examining their underlying methodologies, key applications, and performance characteristics. Framed within the broader context of deep learning for protein representation encoding research, we explore how these approaches individually and collectively contribute to advancing our understanding of protein function, interaction, and evolution. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, understanding the strengths and limitations of each paradigm is crucial for selecting appropriate methodologies for specific protein-related prediction tasks.

Feature-Based Approaches

Core Concept and Methodology

Feature-based approaches represent the traditional paradigm in protein bioinformatics, relying on expert-curated features and domain knowledge to represent protein characteristics. These methods transform raw amino acid sequences into structured numerical representations using handcrafted features derived from physicochemical properties, evolutionary information, and structural predictions [2]. The feature engineering process typically incorporates amino acid composition, hydrophobicity scales, charge distributions, and other biophysical properties that influence protein structure and function.

These approaches often leverage multiple sequence alignments (MSA) of homologous proteins to extract evolutionary constraints through position-specific scoring matrices (PSSMs), conservation scores, and co-evolutionary patterns [26]. The fundamental premise is that positions critical for function or structure remain conserved through evolution, while other positions may exhibit greater variability. Feature-based methods excel at capturing local structural environments and functional constraints that may not be immediately apparent from sequence alone.

Key Techniques and Implementation

Evolutionary Feature Extraction: The most powerful feature-based representations incorporate evolutionary information through MSAs. Tools like HHblits or PSI-BLAST generate PSSMs that quantify the likelihood of each amino acid occurring at each position based on homologous sequences [26]. Additional features include conservation scores (e.g., Shannon entropy), mutual information for detecting co-evolving residues, and phylogenetic relationships.

Physicochemical Property Encoding: Each amino acid can be represented by its intrinsic biophysical properties, including molecular weight, hydrophobicity index, charge, polarity, and side-chain volume. These properties are typically normalized and combined into feature vectors that capture the biochemical characteristics of protein sequences [2].

Structural Feature Prediction: Even without experimental structures, feature-based methods can incorporate predicted structural attributes such as secondary structure (alpha-helices, beta-sheets, coils), solvent accessibility, disorder regions, and backbone torsion angles. These features are typically predicted from sequence using tools like SPOT-1D or similar algorithms [2].

Table 1: Key Feature Categories in Feature-Based Approaches

| Feature Category | Specific Examples | Biological Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Evolutionary Features | PSSMs, conservation scores, co-evolution signals | Functional importance, structural constraints |

| Physicochemical Features | Hydrophobicity, charge, polarity, volume | Stability, binding interfaces, solubility |

| Structural Features | Secondary structure, solvent accessibility, disorder | Folding patterns, functional regions, flexibility |

| Compositional Features | Amino acid composition, dipeptide frequency | Sequence bias, functional class indicators |

Applications and Performance

Feature-based approaches have demonstrated strong performance across various protein prediction tasks, particularly when training data is limited. They remain competitive for function annotation, especially when combined with traditional machine learning classifiers like support vector machines or random forests [15]. These methods are particularly valuable for detecting functional sites and residues through patterns of conservation and co-evolution in MSAs [26].

The main advantage of feature-based approaches lies in their interpretability—the relationship between input features and model predictions is often more transparent than in deep learning models. However, these methods are limited by the quality and completeness of the feature engineering process and may miss complex, higher-order patterns that deep learning models can capture automatically from raw data [2].

Sequence-Based Approaches

Core Concept and Methodology

Sequence-based approaches represent a paradigm shift from handcrafted features to automated representation learning directly from amino acid sequences. These methods treat proteins as biological language, applying natural language processing techniques to learn meaningful representations from unlabeled protein sequences [25] [2]. The core insight is that statistical patterns in massive sequence databases encode fundamental principles of protein structure and function.

Protein Language Models (PLMs), such as ESM (Evolutionary Scale Modeling) and ProtTrans, have become the cornerstone of modern sequence-based approaches [2]. These models employ transformer architectures trained on millions of protein sequences through self-supervised objectives, typically predicting masked amino acids based on their context. Through this process, PLMs learn rich, contextual representations that capture structural, functional, and evolutionary information without explicit supervision [2].

Key Techniques and Implementation

Protein Language Models: Large-scale PLMs like ESM-2 and Prot-T5 leverage transformer architectures with attention mechanisms to capture long-range dependencies in protein sequences [2]. These models process sequences of amino acids analogous to how language models process sequences of words, learning contextual embeddings for each residue that encode information about its structural and functional role.

End-to-End Learning: Sequence-based approaches often employ end-to-end architectures where the representation learning and task-specific prediction are jointly optimized [25]. This allows the model to learn features specifically relevant to the target task, rather than relying on fixed, general-purpose representations.

Transfer Learning: Pre-trained PLMs can be fine-tuned on specific downstream tasks with limited labeled data, leveraging knowledge acquired from large-scale unsupervised pre-training [25] [2]. This approach has proven particularly effective for specialized prediction tasks where collecting large labeled datasets is challenging.

Applications and Performance

Sequence-based approaches have achieved state-of-the-art performance across diverse protein prediction tasks. PLMs have demonstrated remarkable capability in predicting secondary structure, disorder regions, binding sites, and mutation effects without explicit structural information [2]. The ESM model family has shown particular strength in zero-shot mutation effect prediction, accurately identifying stabilizing and destabilizing mutations based solely on sequence information [2].

For protein engineering, sequence-based models like SESNet have outperformed other methods in predicting the fitness of protein variants, achieving superior correlation with experimental measurements in deep mutational scanning studies [27]. These models effectively capture global evolutionary patterns from massive sequence databases, enabling accurate prediction of functional consequences of single and multiple mutations.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Sequence-Based Models on DMS Datasets

| Model | Type | Average Spearman ρ | Key Strengths |

|---|---|---|---|

| SESNet | Supervised | 0.672 | Integrates local/global sequence and structural features |

| ECNet | Supervised | 0.639 | Evolutionary context from homologous sequences |

| ESM-1b | Supervised | 0.630 | Protein language model representations |

| ESM-1v | Unsupervised | 0.520 | Zero-shot variant effect prediction |

| MSA Transformer | Unsupervised | 0.510 | Co-evolutionary patterns from MSAs |

Structure-Based Approaches

Core Concept and Methodology

Structure-based approaches leverage the fundamental principle that protein function is determined by three-dimensional structure. These methods employ geometric deep learning to represent and analyze the spatial arrangement of atoms, residues, and secondary structure elements [2] [28]. The paradigm has been revolutionized by accurate structure prediction tools like AlphaFold2 and ESMFold, which provide high-quality structural models for virtually any protein sequence [2] [15].

These approaches represent proteins as graphs, point clouds, or 3D grids, enabling models to capture physical and chemical interactions within the structural environment [28]. Key representations include distance maps, torsion angles, surface maps, and atomic coordinates, each offering different advantages for specific prediction tasks [28]. Structure-based methods are particularly valuable for predicting binding sites, protein-protein interactions, and functional effects of mutations that alter protein stability or interaction interfaces [26].

Key Techniques and Implementation

Graph Neural Networks (GNNs): GNNs represent proteins as graphs where nodes correspond to residues or atoms, and edges represent spatial proximity or chemical bonds [2] [15]. Message-passing mechanisms allow information to propagate through the graph, capturing the local structural environment and long-range interactions through multiple layers.

Geometric Representations: SE(3)-equivariant networks explicitly model the 3D geometry of proteins, maintaining consistency with rotations and translations [2]. These approaches are particularly valuable for tasks requiring orientation awareness, such as molecular docking or protein design.

Structure Featurization: Protein structures are encoded using various schemes, including:

- Distance maps (2D matrices of inter-residue distances)

- Voronoi tessellations (spatial partitioning of protein structures)

- Surface maps (shape and electrostatic properties)

- Voxelized representations (3D grids of structural and chemical features) [28]

Applications and Performance

Structure-based approaches have demonstrated exceptional performance in predicting protein function and interaction sites. DPFunc, a method that integrates domain-guided structure information, has shown significant improvements over sequence-based methods, achieving performance increases of 16-27% in Fmax scores across molecular function, cellular component, and biological process ontologies [15]. The incorporation of domain information helps identify key functional regions within structures, enhancing both accuracy and interpretability.

For protein engineering, structure-based approaches provide critical insights into how mutations affect stability and binding. Methods that explicitly model structural constraints have proven valuable for predicting the fitness of higher-order mutants, where multiple mutations may have cooperative effects that are difficult to capture from sequence alone [27]. Structure-based models also excel at predicting protein-ligand and protein-protein interactions by analyzing complementarity at interaction interfaces [2].

Integrated and Hybrid Approaches

Multi-Modal Integration Strategies

The most advanced protein representation approaches integrate multiple paradigms to leverage their complementary strengths. Integrated models combine sequence, structure, and evolutionary information to create comprehensive representations that capture different aspects of protein function [2] [27]. These hybrid approaches have demonstrated state-of-the-art performance across diverse prediction tasks.

SESNet exemplifies this integration, combining local evolutionary context from MSAs, global semantic context from protein language models, and structural microenvironments from 3D structures [27]. The model employs attention mechanisms to dynamically weight the importance of different information sources, achieving superior performance in predicting protein fitness from deep mutational scanning data [27]. Ablation studies confirmed that all three components contribute significantly to model performance, with the global sequence encoder providing the most substantial individual contribution [27].

Implementation Frameworks

Attention-Based Fusion: Multi-modal architectures often use attention mechanisms to integrate representations from different paradigms [15] [27]. These approaches learn to assign importance weights to different features or modalities based on their relevance to the prediction task.

Graph-Based Integration: Methods like DPFunc represent protein structures as graphs while incorporating domain information from sequences [15]. Domain definitions guide the model to focus on structurally coherent regions with functional significance, enhancing both performance and interpretability.

Geometric and Semantic Fusion: Advanced models jointly encode geometric structure (3D coordinates) and semantic information (sequence embeddings) using specialized architectures that preserve the unique properties of each modality while enabling cross-modal information exchange [27].

Table 3: The Researcher's Toolkit for Protein Representation Learning

| Tool/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Structure Prediction | AlphaFold2, AlphaFold3, ESMFold | Generate 3D models from sequences |

| Protein Language Models | ESM-2, ProtTrans | Learn contextual sequence representations |

| Domain Detection | InterProScan | Identify functional domains in sequences |

| Geometric Learning | GNNs, SE(3)-equivariant networks | Process 3D structural information |

| Multiple Sequence Alignment | HHblits, PSI-BLAST | Extract evolutionary constraints |

| Function Annotation | DPFunc, DeepFRI, GAT-GO | Predict protein function from structure/sequence |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol for Structure-Based Function Prediction

DPFunc Methodology [15]:

- Input Processing: Generate or retrieve 3D protein structures (experimental or predicted using AlphaFold2). Extract protein sequences and identify functional domains using InterProScan.

- Residue-Level Feature Extraction: Generate initial residue features using pre-trained protein language models (ESM-1b). Construct contact maps from 3D structures.

- Graph Construction: Represent proteins as graphs where nodes correspond to residues and edges represent spatial contacts. Apply Graph Convolutional Networks (GCNs) with residual connections to propagate and update residue features.

- Domain-Guided Attention: Convert detected domains into dense representations via embedding layers. Apply attention mechanisms to weight residue importance under domain guidance.

- Function Prediction: Aggregate weighted residue features into protein-level representations. Pass through fully connected layers for function prediction using Gene Ontology terms.

- Post-Processing: Apply consistency checks with GO term structure to ensure biologically plausible predictions.

Protocol for Sequence-Structure Fitness Prediction

SESNet Methodology [27]:

- Multi-Modal Encoding:

- Local encoder: Process multiple sequence alignments to capture residue interdependence

- Global encoder: Extract features using protein language models (ESM-1b)

- Structure module: Encode 3D structural microenvironments around each residue

- Feature Integration: Concatenate local and global sequence representations. Apply attention mechanisms to generate sequence attention weights.

- Attention Fusion: Average sequence attention weights with structure-derived attention weights to create combined attention weights.

- Fitness Prediction: Compute weighted sum of integrated sequence representations using combined attention weights. Pass through fully connected layers to predict fitness.

- Key Site Identification: Use combined attention weights to identify residues critical for protein fitness.

Data Augmentation and Training Strategy

Transfer Learning Protocol [27]:

- Pre-Training Phase: Train model on large-scale unsupervised data (millions of sequences) or low-quality fitness predictions from unsupervised models.

- Fine-Tuning Phase: Transfer learned representations to target protein using limited experimental data (as few as 40 measurements).

- Evaluation: Assess performance on held-out variants, particularly higher-order mutants (>4 mutation sites).

The three major paradigms—feature-based, sequence-based, and structure-based approaches—each contribute unique capabilities to protein representation learning. Feature-based methods provide interpretable representations grounded in domain knowledge; sequence-based approaches leverage evolutionary information through protein language models; and structure-based methods capture the spatial determinants of function. The most powerful contemporary solutions integrate these paradigms, creating multi-modal representations that exceed the capabilities of any single approach.

As the field advances, key challenges remain in improving interpretability, handling multi-chain complexes, and predicting dynamic protein behavior. The development of methods that can seamlessly integrate diverse data types while providing biologically meaningful insights will continue to drive progress in protein science and accelerate drug discovery and protein engineering applications.

The hierarchical organization of proteins—from their primary amino acid sequence to the assembly of multi-subunit complexes—forms the foundational framework upon which biological function is built. This hierarchy, traditionally categorized into primary, secondary, tertiary, and quaternary structures, dictates everything from enzymatic catalysis to cellular signaling. In the era of computational biology, deep learning has revolutionized our ability to decipher and predict these structural levels, transforming protein science and drug discovery. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical examination of these critical biological hierarchies, framed within the context of modern deep learning approaches for protein representation encoding. We dissect the core structural elements, detail the experimental and computational methodologies for their study, and present quantitative performance data on state-of-the-art prediction tools, equipping researchers with the knowledge to leverage these advancements in therapeutic development.

The Hierarchical Organization of Protein Structures

Protein structure is organized into four distinct yet interconnected levels, each with increasing complexity and functional implications. The primary structure is the linear sequence of amino acids determined by the genetic code, forming the fundamental blueprint from which all higher-order structures emerge [29] [30]. These amino acid chains then fold into local regular patterns known as secondary structures, predominantly alpha-helices and beta-sheets, stabilized by hydrogen bonds between backbone atoms [29] [30]. The tertiary structure describes the three-dimensional folding of a single polypeptide chain, bringing distant secondary structural elements into spatial proximity to form functional domains [30]. Finally, multiple folded polypeptide chains (subunits) associate to form quaternary structures, creating complex molecular machines with emergent functional capabilities [30].

Table 1: Defining the Four Levels of Protein Structural Hierarchy

| Structural Level | Definition | Stabilizing Forces | Key Functional Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary | Linear sequence of amino acids | Covalent peptide bonds | Determines all higher-order folding; contains catalytic residues |

| Secondary | Local folding patterns (alpha-helices, beta-sheets) | Hydrogen bonding between backbone atoms | Provides structural motifs; mechanical properties |

| Tertiary | Three-dimensional folding of a single chain | Hydrophobic interactions, disulfide bridges, hydrogen bonds | Creates binding pockets and catalytic sites; defines domain architecture |

| Quaternary | Assembly of multiple polypeptide chains | Non-covalent interactions between subunits | Enables allosteric regulation; creates multi-functional complexes |

The relationship between these hierarchical levels is not strictly linear but involves complex interdependencies. While Anfinsen's dogma established that the tertiary structure is determined by the primary sequence, the folding process faces the Levinthal paradox—the theoretical impossibility of randomly sampling all possible conformations within biologically relevant timescales [29] [18]. This paradox highlights the sophisticated nature of protein folding and the necessity for advanced computational approaches to predict its outcomes. Deep learning models effectively navigate this complexity by learning the intricate mapping between sequence and structure from known examples, bypassing the need for exhaustive conformational sampling.

Deep Learning for Protein Structure Prediction and Representation

Deep learning has emerged as a transformative technology for protein structure prediction, leveraging neural networks to decode the relationships between sequence and structure across all hierarchical levels. Several architectural paradigms have proven particularly effective for this domain.

Key Deep Learning Architectures

Transformer-based models, initially developed for natural language processing, treat protein sequences as "sentences" where amino acids represent "words." Models like ESM (Evolutionary Scale Modeling) and ProtTrans learn contextualized embeddings for each residue by training on millions of protein sequences, capturing evolutionary patterns and biochemical properties [2]. These embeddings serve as rich input features for various downstream prediction tasks. Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) explicitly model proteins as graphs where nodes represent amino acids and edges represent spatial or functional relationships [2] [3]. GNN variants including Graph Convolutional Networks (GCNs), Graph Attention Networks (GATs), and Graph Autoencoders have demonstrated exceptional capability in modeling protein-protein interactions and structural relationships by propagating information between connected nodes [3]. Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) and SE(3)-equivariant networks specialize in processing spatial and structural data, maintaining consistency with rotational and translational symmetries inherent in 3D molecular structures [2].

Representative Models and Applications

AlphaFold2 represents a landmark achievement in tertiary structure prediction, employing an attention-based neural network to achieve atomic accuracy [31]. Its extension, AlphaFold3, generalizes this approach to predict quaternary structures and protein complexes with other biomolecules [2] [31]. For protein function annotation, DPFunc integrates domain-guided structure information with deep learning to predict Gene Ontology terms, outperforming sequence-based methods by leveraging structural context [15]. In the challenging area of multidomain protein prediction, D-I-TASSER combines deep learning potentials with iterative threading assembly refinement, demonstrating complementary strengths to AlphaFold2 especially for complex multi-domain targets [32].

Quantitative Performance of Deep Learning Models

Rigorous benchmarking provides critical insights into the current capabilities and limitations of deep learning approaches across different protein prediction tasks.

Table 2: Benchmark Performance of Structure Prediction Methods on Single-Domain Proteins

| Method | Average TM-Score | Fold Recovery Rate (TM-Score > 0.5) | Key Strengths |

|---|---|---|---|

| D-I-TASSER | 0.870 | 96% (480/500 domains) | Excels on difficult targets; integrates physical simulations |

| AlphaFold3 | 0.849 | 94% | End-to-end learning; molecular interactions |

| AlphaFold2.3 | 0.829 | 92% | High accuracy on typical domains |

| C-I-TASSER | 0.569 | 66% (329/500 domains) | Contact-based restraints |

| I-TASSER | 0.419 | 29% (145/500 domains) | Template-based modeling |

Data compiled from benchmark tests on 500 nonredundant 'Hard' domains from SCOPe, PDB, and CASP experiments, where no significant templates (>30% sequence identity) were available [32]. D-I-TASSER demonstrated statistically significant superiority over all AlphaFold versions (P < 1.79×10^-7) [32].

For protein function prediction, DPFunc achieves substantial improvements over existing methods across Gene Ontology categories. On molecular function (MF) prediction, DPFunc achieves an Fmax of 0.780 compared to 0.673 for GAT-GO and 0.633 for DeepFRI. Similarly, for biological process (BP) prediction, DPFunc reaches an Fmax of 0.681 versus 0.552 for GAT-GO and 0.454 for DeepFRI [15]. These improvements highlight the value of incorporating domain-guided structural information rather than treating all amino acids equally in function prediction.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol: Deep Learning-Based Protein Structure Prediction with D-I-TASSER

The D-I-TASSER pipeline exemplifies the integration of deep learning with physics-based simulations for high-accuracy structure prediction [32]:

- Deep Multiple Sequence Alignment Construction: Iteratively search genomic and metagenomic sequence databases using hidden Markov models. Select optimal MSA through rapid deep-learning-guided evaluation.

- Spatial Restraint Generation: Generate complementary spatial restraints using multiple deep learning approaches:

- DeepPotential: Residual convolutional networks predict contact/distance maps.

- AttentionPotential: Self-attention transformer networks capture long-range interactions.

- AlphaFold2: Incorporate end-to-end neural network predictions.

- Template Identification: Run LOcal MEta-Threading Server (LOMETS3) to identify structural fragments from PDB templates.

- Replica-Exchange Monte Carlo Assembly: Assemble full-length models through replica-exchange Monte Carlo simulations guided by a hybrid force field combining:

- Deep learning-derived spatial restraints

- Knowledge-based potential terms

- Physical energy functions

- Model Selection and Refinement: Select top models based on structural quality assessment. Perform atomic-level refinement using energy minimization.

For multidomain proteins, D-I-TASSER incorporates an additional domain partitioning step where domain boundaries are predicted, and steps 1-4 are performed iteratively for individual domains before final complex assembly with interdomain restraints [32].

Protocol: Protein Function Prediction with DPFunc

DPFunc integrates sequence and structural information for protein function prediction [15]:

- Residue-Level Feature Extraction:

- Generate initial residue embeddings using pre-trained protein language model (ESM-1b).

- Construct contact maps from experimental (PDB) or predicted (AlphaFold) structures.

- Process through Graph Convolutional Network layers with residual connections to update features.

- Domain-Guided Attention:

- Identify functional domains using InterProScan against background databases.

- Convert domain entries to dense representations via embedding layers.

- Apply attention mechanism to weight residue importance guided by domain information.

- Protein-Level Feature Integration:

- Compute weighted sum of residue features using attention weights.

- Combine with initial residue embeddings for comprehensive representation.

- Function Prediction and Consistency:

- Process through fully connected layers to predict Gene Ontology terms.

- Apply post-processing to ensure consistency with GO hierarchical structure.

Table 3: Key Databases and Tools for Protein Structure and Function Research

| Resource | Type | Primary Use | URL/Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protein Data Bank (PDB) | Database | Experimental protein structures | https://www.rcsb.org/ [3] |

| AlphaFold Protein Structure Database | Database | Predicted structures for ~200 million proteins | https://alphafold.ebi.ac.uk/ [31] |

| STRING | Database | Known and predicted protein-protein interactions | https://string-db.org/ [3] |

| InterProScan | Tool | Protein domain family identification | [15] |

| D-I-TASSER | Tool | Single and multidomain protein structure prediction | https://zhanggroup.org/D-I-TASSER/ [32] |

| DPFunc | Tool | Protein function prediction with domain guidance | [15] |

| ESM-1b/ESM-2 | Model | Protein language model for sequence representations | [2] [15] |

| Gene Ontology (GO) | Database | Standardized functional terminology | [2] [15] |

The hierarchical organization of proteins—from residues to complexes—represents both a fundamental biological principle and a computational framework for understanding function. Deep learning has dramatically advanced our ability to navigate this hierarchy, with models like AlphaFold, D-I-TASSER, and DPFunc providing unprecedented accuracy in structure and function prediction. Current challenges remain in predicting conformational dynamics, modeling orphan proteins with limited homology, and understanding allosteric regulation mechanisms. Future directions will likely involve integrating temporal dimensions for folding pathways, expanding to non-protein molecules, and developing generative models for de novo protein design. As these technologies mature, they will continue to transform drug discovery, enzyme engineering, and our fundamental understanding of life's molecular machinery.

Advanced Architectures and Real-World Applications in Protein Encoding

The application of deep learning to protein science represents a paradigm shift in computational biology. Central to this revolution is protein representation encoding, the process of converting the discrete amino acid sequences of proteins into continuous, meaningful numerical vectors that machine learning models can process. Within this domain, sequence-based models, particularly Protein Language Models (PLMs) and Evolutionary Scale Modeling (ESM), have emerged as foundational technologies. These models treat amino acid sequences as a form of "biological language," allowing them to learn the complex statistical patterns and "grammar" that govern protein structure and function from vast sequence databases [12] [33]. By capturing the evolutionary constraints and biophysical principles embedded in millions of natural protein sequences, these models provide powerful representations that drive advances in protein engineering, function prediction, and therapeutic design [34].

This technical guide explores the core architectures, training methodologies, and applications of these sequence-based models, framing them within the broader deep learning landscape for protein representation encoding. We detail the experimental protocols for their application and provide a toolkit for researchers seeking to leverage these transformative technologies.

Core Architectural Principles of Protein Language Models

The Biological Analogy to Natural Language Processing