Beyond the Training Set: Mastering Dataset Shift for Accurate Protein-Ligand Interaction Prediction

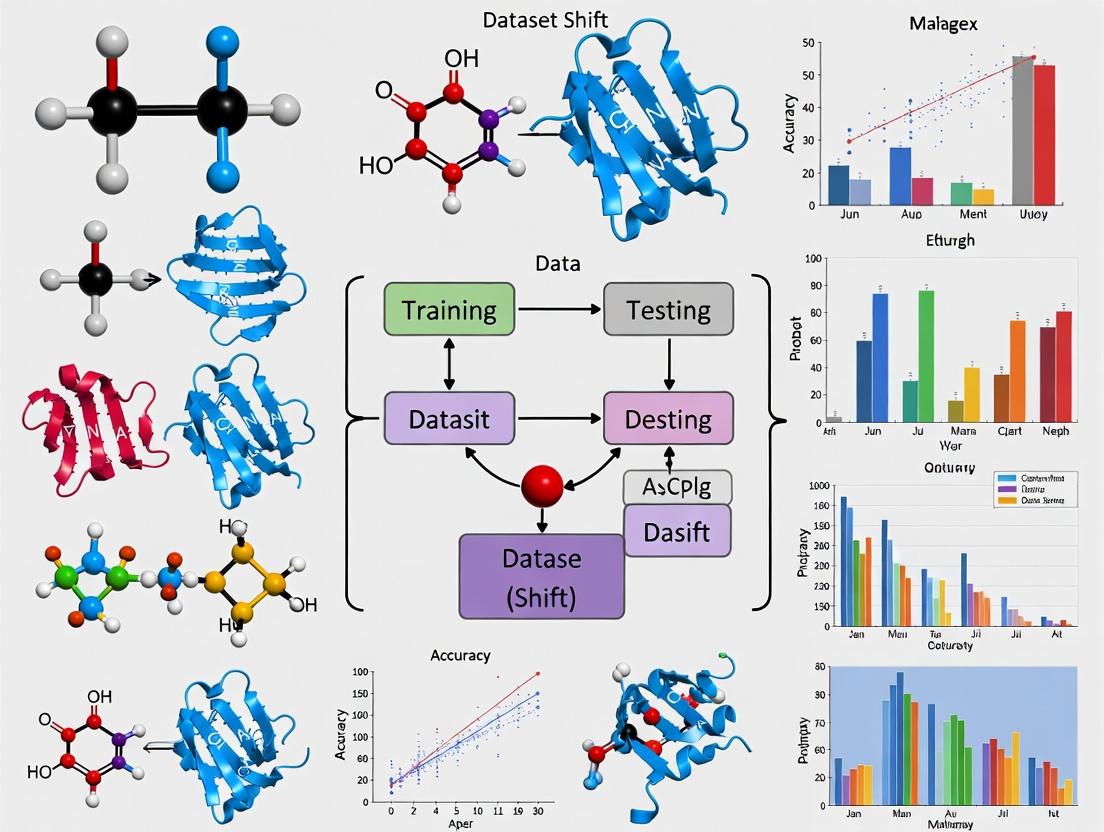

This article addresses the critical challenge of dataset shift in machine learning models for protein-ligand interaction (PLI) prediction, a major bottleneck in AI-driven drug discovery.

Beyond the Training Set: Mastering Dataset Shift for Accurate Protein-Ligand Interaction Prediction

Abstract

This article addresses the critical challenge of dataset shift in machine learning models for protein-ligand interaction (PLI) prediction, a major bottleneck in AI-driven drug discovery. We explore the foundational concepts of dataset shift (covariate, concept, and label shift) and their specific manifestations in PLI data, such as scaffold hopping and binding site variability. Methodological solutions, including domain adaptation, data augmentation with generative models, and uncertainty quantification, are examined for practical application. The guide provides troubleshooting strategies for model failure and outlines rigorous validation frameworks to ensure model robustness and reliability in real-world scenarios. This comprehensive resource equips researchers and drug development professionals with the knowledge to build predictive models that generalize beyond their initial training data, accelerating the discovery pipeline.

What is Dataset Shift? The Silent Saboteur of AI in Drug Discovery

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting Guide for Dataset Shift in Protein-Ligand Interaction Prediction

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My model, trained on assay data from a specific kinase family, performs poorly when predicting interactions for a newly discovered kinase in the same family. What type of dataset shift is this likely to be? A: This is a classic case of Covariate Shift (X→P(X) changes). The model's performance degrades because the input feature distribution has changed. The new kinase, while evolutionarily related, presents distinct physicochemical properties in its binding pocket (e.g., different amino acid distributions, solvation, or backbone conformations) compared to the kinases in your training set. The conditional probability of the interaction given the features, P(Y|X), remains valid, but the model is now applied to a new region of the feature space it was not trained on.

Q2: I am using the same experimental assay (e.g., SPR), but the binding affinity thresholds defining "active" vs. "inactive" have been revised by the field. My old labels are now obsolete. What shift is occurring? A: This is Concept Shift (P(Y|X) changes). The fundamental relationship between the molecular features (X) and the target label (Y) has changed over time. A compound with a given feature vector that was previously labeled as "active" (Kd = 10µM) may now be considered "inactive" under a new, stricter definition (e.g., Kd < 1µM). The data distribution P(X) may be unchanged, but the mapping from X to Y has evolved.

Q3: My training data is heavily skewed towards high-affinity binders from high-throughput screens, but my real-world application requires identifying weak binders for fragment-based drug discovery. What is the core problem? A: This is Label Shift/Prior Probability Shift (P(Y) changes). The prevalence of different output classes differs between your training and deployment environments. Your training set has a very high prior probability P(Y="high-affinity"), but in deployment, the prior for P(Y="weak-affinity") is much higher. If not corrected, your model will be biased towards predicting high-affinity interactions.

Q4: How can I diagnose which type of shift is affecting my model before attempting to fix it? A: Follow this diagnostic workflow:

Diagram Title: Diagnostic Workflow for Dataset Shift Types

Experimental Protocols for Identifying Shift

Protocol 1: Detecting Covariate Shift using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov Test Objective: Quantify the difference in distributions for a single key molecular descriptor (e.g., Molecular Weight) between training and deployment datasets. Steps:

- Extract the descriptor for all compounds in your training set (Xtrain) and your new target set (Xtarget).

- Formulate hypotheses:

- H0: The two samples are from the same continuous distribution.

- H1: The two samples are from different distributions.

- Compute the KS statistic: D = supx |Ftrain(x) - F_target(x)|, where F is the empirical cumulative distribution function.

- Calculate the p-value. A p-value < 0.05 suggests a significant difference, indicating covariate shift for that feature.

- Repeat for other critical descriptors (e.g., logP, rotatable bonds, protein sequence identity).

Protocol 2: Benchmarking for Concept Shift using a Temporal Holdout Objective: Assess if model performance decays over time due to changing label definitions. Steps:

- Split your data chronologically by assay date, not randomly.

- Train your model on data from years 2010-2015.

- Create multiple test sets: Test2016, Test2017, Test_2018.

- Evaluate performance (AUC, F1) on each sequential test set.

- A consistent, significant decrease in performance over time suggests concept drift.

Protocol 3: Quantifying Label Shift using Black-Box Shift Estimation (BBSE) Objective: Estimate the new class priors P_target(Y) in the unlabeled target data. Steps:

- Train a calibrated classifier (e.g., Platt-scaled Logistic Regression) on your source/training data. This estimates P(Y|X).

- Apply this classifier to the unlabeled target data to obtain a confusion matrix C_hat of predictions.

- Use the source data label proportions Psource(Y) and Chat to solve for Ptarget(Y) via the equation: µtarget = Chat * µsource, where µ is the class probability vector.

- Compare estimated Ptarget(Y) to Psource(Y). Large differences confirm label shift.

Table 1: Common Biomolecular Data Sources and Their Associated Shift Risks

| Data Source | Typical Use | Common Shift Type | Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|

| PDBbind (Refined Set) | Training/Validation | Covariate Shift | Curated high-resolution structures; new drug targets have different protein fold distributions. |

| ChEMBL (Bioactivity Data) | Large-scale Training | Concept & Label Shift | Assay protocols/Kd thresholds evolve; data is biased towards popular target families. |

| Company HTS Legacy Data | Primary Training | Label Shift | Heavily skewed towards historic project targets, not representative of new therapeutic areas. |

| Real-World HTS Campaign | Deployment/Application | Covariate & Label Shift | Chemical library and target of interest differ from public data sources. |

Table 2: Quantitative Impact of Dataset Shift on Model Performance (Hypothetical Study)

| Shift Type | Training AUC | Test AUC (IID*) | Test AUC (Shifted) | Performance Drop | Recommended Mitigation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Covariate (New Kinase) | 0.92 | 0.90 | 0.75 | -16.7% | Domain-Adversarial Neural Network |

| Concept (New IC50 Threshold) | 0.88 | 0.87 | 0.65 | -22.2% | Retrain with relabeled data |

| Label (Different Class Balance) | 0.95 | 0.94 | 0.82 | -12.0% | Prior Probability Reweighting |

| Combined Shift | 0.90 | 0.89 | 0.58 | -31.1% | Integrated pipeline (e.g., Causal Adaptation) |

*IID: Independent and Identically Distributed test data from the same source.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Resources for Managing Dataset Shift

| Item/Resource | Function in Addressing Shift | Example/Provider |

|---|---|---|

| Domain Adaptation Algorithms | Learn transferable features between source (training) and target (deployment) domains. | DANN (Domain-Adversarial Neural Networks), CORAL (Correlation Alignment). |

| Causal Inference Frameworks | Isolate stable, invariant predictive relationships from spurious correlations. | Invariant Risk Minimization (IRM), Causal graphs for feature selection. |

| Uncertainty Quantification Tools | Estimate model prediction confidence; high uncertainty often indicates shift. | Monte Carlo Dropout, Deep Ensembles, Conformal Prediction. |

| Benchmark Datasets | Standardized testbeds for evaluating shift robustness. | PDBbind temporal splits, TDC (Therapeutics Data Commons) out-of-distribution benchmarks. |

| Calibration Software | Ensure predicted probabilities reflect true likelihoods, critical for label shift correction. | Platt Scaling, Isotonic Regression (via scikit-learn). |

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guide

Q1: My PLI model performs well on the training/validation set but fails on new external test sets from different sources. What is happening? A: This is a classic symptom of dataset shift, specifically covariate shift. The training data likely underrepresents the chemical and protein structural space of the new test set. The model learned spurious correlations specific to the training distribution.

Experimental Protocol to Diagnose Covariate Shift:

- Descriptor Calculation: Compute standardized molecular descriptors (e.g., from RDKit) for all ligands in both training (Tr) and new external (Ex) sets. For proteins, use features like amino acid composition or sequence embeddings.

- Dimensionality Reduction: Apply PCA or UMAP to reduce descriptors to 2-3 principal components.

- Visualization & Quantitative Test: Plot the distributions of Tr and Ex sets. Perform a statistical test like the Two-Sample Kolmogorov-Smirnov (KS) test on the first principal component.

- Interpretation: A significant KS test p-value (< 0.05) indicates a difference in distributions, confirming covariate shift.

Q2: My model shows high predictive accuracy for certain protein families but completely fails for others. How can I identify this bias? A: This indicates prior probability shift and bias in the training data. The model has likely not seen sufficient examples of the underperforming protein families or their binding mechanisms.

Experimental Protocol to Identify Family-Level Bias:

- Stratify by Protein Family: Classify all proteins in your dataset into families (e.g., using CATH or Pfam).

- Performance Analysis: Calculate model performance metrics (AUC-ROC, RMSE) separately for each family.

- Correlation with Data Density: Plot performance metric vs. the log(number of samples) for each family.

Quantitative Bias Analysis Table: Table 1: Example Analysis Revealing Performance Bias Across Protein Families

| Protein Family (Pfam ID) | Number of Complexes in Training Data | Test AUC-ROC | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kinase (PF00069) | 12,450 | 0.92 | Overrepresented, high performance |

| GPCR (PF00001) | 8,120 | 0.88 | Well-represented, good performance |

| Nuclear Receptor (PF00104) | 950 | 0.76 | Moderately represented, lower performance |

| Ion Channel (PF00520) | 427 | 0.62 | Sparse data, poor performance |

| Viral Protease (PF00077) | 89 | 0.51 | Highly sparse, model failure |

Q3: How can I check if negative samples (non-binders) in my dataset are creating unrealistic biases? A: Many PLI datasets use randomly paired or "decoy" ligands as negatives, which may be too easy to distinguish, leading to artificially inflated performance and poor generalization.

Experimental Protocol for Negative Sample Analysis:

- Assay Comparison: If possible, compare your model's performance on a dataset with random negatives vs. a benchmark with experimentally confirmed negatives (e.g., from competitive binding assays).

- Hard Negative Mining: Use similarity searches or docking scores to select non-binders that are chemically similar to known binders ("hard negatives"). Retrain and re-evaluate the model.

- Metric Shift: Observe the change in key metrics. A significant drop in performance with hard negatives indicates vulnerability to negative sample bias.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q: What are the most common sources of sparse and biased data in PLI? A:

- Experimental Bias: Structural databases (PDB) are biased toward soluble, stable, and crystallizable proteins (e.g., kinases), underrepresenting membrane proteins.

- Affinity Bias: Public affinity data (Ki, Kd) is skewed toward potent inhibitors (nanomolar range), with few weak binders or non-binders.

- Temporal Bias: Newly discovered target classes (e.g., CRISPR-associated proteins) have orders of magnitude less data than historic targets.

- Annotation Bias: "Inactive" labels are often computationally generated decoys, not experimentally verified non-binders.

Q: What practical steps can I take to make my PLI model more robust to dataset shift? A:

- Data Auditing: Use the diagnostic protocols above before model training.

- Strategic Sampling: Employ techniques like domain-informed stratified sampling to ensure all protein families are represented in splits, not just random splitting.

- Algorithmic Choice: Consider models designed for domain adaptation or that incorporate uncertainty quantification (e.g., deep ensembles, Gaussian processes).

- Data Augmentation: Use physics-informed in-silico augmentation (e.g., molecular dynamics conformer generation, binding site point cloud perturbations) to carefully expand data diversity.

Q: Are there specific metrics I should report beyond standard AUC/ RMSE to highlight model robustness? A: Yes. Always report domain-specific performance. Include metrics calculated per-protein-family, per-affinity-range, and—critically—on held-out, temporally forward, or orthogonal experimental test sets. Report the standard deviation of performance across these subgroups to indicate stability.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials & Resources for Robust PLI Research

| Item/Resource | Function in Addressing Data Sparsity & Bias |

|---|---|

| PDBbind (refined/general sets) | Provides curated protein-ligand complexes with affinity data. Use for initial training but be aware of its crystallography bias. |

| ChEMBL | Large-scale bioactivity database. Essential for extracting ligand-protein interaction data across diverse targets and affinity ranges. Use for negative sampling with caution. |

| Pfam / CATH Databases | Protein family and fold classification tools. Critical for stratifying your dataset to audit and control for biological bias. |

| RDKit or Mordred | Open-source cheminformatics toolkits. Calculate standardized molecular descriptors to analyze chemical space coverage and covariate shift. |

| DGL-LifeSci or PyTor Geometric | Graph neural network libraries tailored for molecules. Facilitate building models that learn from molecular graph structure directly. |

| AlphaFold DB | Repository of predicted protein structures. Can expand structural coverage for proteins without experimental 3D structures, but lacks dynamics and ligand information. |

| MD Simulation Software (GROMACS, AMBER) | Molecular dynamics packages. Used for generating conformational ensembles of protein-ligand complexes, providing a form of physics-based data augmentation. |

| Hard Negative Benchmark Sets (e.g., DUD-E, LIT-PCBA) | Provide carefully crafted decoy molecules that are chemically similar to actives. Vital for testing model generalizability beyond trivial discrimination. |

Experimental Workflow & Pathway Diagrams

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Q1: My predictive model performs well on the training set but poorly on new, structurally diverse ligands. What could be the cause? A1: This is a classic sign of dataset shift due to scaffold hopping. Your training data likely lacks sufficient chemotype diversity, causing the model to overfit to specific molecular frameworks and fail to generalize.

- Diagnostic Check: Calculate the Tanimoto coefficient or a 3D shape similarity metric between your training and test set scaffolds. Low average similarity confirms this issue.

- Solution: Incorporate a more diverse compound library in training. Use data augmentation techniques like SMILES enumeration or employ domain adaptation algorithms specifically designed for scaffold hopping scenarios.

Q2: My docking simulations yield inconsistent binding poses for closely related analogs. Why does this happen? A2: The likely culprit is binding pocket conformational changes, such as sidechain rearrangements or backbone movements, induced by specific ligand functionalities. Rigid docking protocols fail to account for this protein flexibility.

- Diagnostic Check: Perform a molecular dynamics (MD) simulation of the apo protein or compare multiple experimental structures (e.g., from the PDB) of the target. Root-mean-square fluctuation (RMSF) analysis will highlight flexible regions.

- Solution: Switch to an induced-fit or ensemble docking protocol. Generate an ensemble of receptor conformations from MD simulations or available crystal structures for docking.

Q3: How can I quantitatively assess if dataset shift is affecting my virtual screening campaign? A3: Measure the statistical distribution of key features between your training data and the screening library.

- Diagnostic Protocol:

- Calculate molecular descriptors (e.g., molecular weight, logP, number of rotatable bonds, polar surface area) for both datasets.

- Perform a two-sample Kolmogorov-Smirnov (K-S) test for each descriptor.

- A significant p-value (<0.05) for multiple descriptors indicates a covariate shift.

Table 1: Example K-S Test Results for Dataset Shift Detection

| Molecular Descriptor | Training Set Mean | Screening Library Mean | K-S Statistic (D) | p-value | Shift Detected? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Weight | 350.2 Da | 410.5 Da | 0.21 | 0.003 | Yes |

| Calculated logP (cLogP) | 2.8 | 3.1 | 0.09 | 0.152 | No |

| Number of H-Bond Donors | 2.1 | 1.8 | 0.12 | 0.065 | No |

| Polar Surface Area | 75.4 Ų | 68.2 Ų | 0.18 | 0.010 | Yes |

Q4: What experimental protocol can validate a predicted binding mode involving pocket rearrangement? A4: Use a combination of computational and biophysical techniques.

- Experimental Validation Protocol:

- Computational Prediction: Use an induced-fit docking workflow to generate the hypothesized protein-ligand complex with the rearranged pocket.

- Site-Directed Mutagenesis: Mutate key flexible residues identified in the model (e.g., a gating residue) to alanine.

- Binding Affinity Assay: Measure the binding affinity (e.g., via ITC or SPR) of the ligand for both the wild-type and mutant protein.

- Expected Outcome: If the predicted rearrangement is critical, the mutation will significantly reduce binding affinity for the specific ligand but may not affect binders that use the canonical conformation.

- Direct Observation (Optimal): Solve a co-crystal structure of the ligand bound to the protein target.

Key Diagrams

Diagram 1: Dataset Shift in PLI Prediction

Diagram 2: Induced-Fit Docking Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Tools for Addressing PLI Prediction Challenges

| Item | Function & Relevance to Dataset Shift |

|---|---|

| Diverse Compound Libraries (e.g., CLEVER, ZINC) | Provides broad chemotype coverage for training and testing, mitigating scaffold hopping failure. |

| Molecular Dynamics Software (e.g., GROMACS, AMBER) | Simulates protein flexibility to generate conformational ensembles, addressing pocket dynamics. |

| Induced-Fit Docking Suite (e.g., Schrödinger IFD, AutoDock Vina with sidechain flexibility) | Accounts for local binding site rearrangements upon ligand binding. |

| Protein Conformation Database (e.g., PDBFlex, Mol* Viewer) | Offers experimental evidence of native protein flexibility for target analysis. |

| Domain Adaptation Algorithms (e.g., DANN, CORAL) | Machine learning methods designed to correct for feature distribution shifts between datasets. |

| Biophysical Validation Kits (e.g., ITC, SPR assays) | Essential for ground-truth binding measurement to validate computational predictions on new chemotypes. |

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting Virtual Screening Failures Due to Dataset Shift

FAQs & Troubleshooting Guides

Q1: My virtual screening model, trained on PDBbind refined set, performs poorly when screening a novel kinase target. The top hits show no activity in assays. What is the likely cause? A: This is a classic case of covalent shift. The PDBbind refined set is heavily biased towards non-covalent interactions. Your novel kinase target may have a cysteine residue in the binding pocket amenable to covalent inhibitors, a feature underrepresented in your training data. Your model lacks the chemical and physical features to recognize reactive warheads like acrylamides.

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Analyze Binding Site: Use a tool like

fpocketorPyMOLto check for reactive nucleophilic residues (e.g., CYS, SER) in your target's binding site. - Enrich Training Data: Incorporate covalent complexes from databases like CovalentInDB or the "covalent" subset of PDBbind into your training set.

- Feature Engineering: Add features describing atom reactivity, warhead presence, and potential bond formation distance to your molecular featurization pipeline.

- Analyze Binding Site: Use a tool like

Q2: After training a high-performance CNN on protein-ligand grids, the model fails to rank-order compounds from an HTS deck for a the same protein target. Why? A: This failure likely stems from ligand property shift. Your training data (e.g., from PDB or CSAR) contains high-affinity, optimized leads with specific physicochemical property ranges. The HTS deck contains diverse, often "drug-like" but not necessarily "target-optimized" compounds, with different distributions of molecular weight, logP, or polarity.

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Conduct Distribution Analysis: Compare the distributions of key molecular descriptors (MW, LogP, TPSA, number of rotatable bonds) between your training complexes and the HTS deck. Use Kolmogorov-Smirnov tests.

- Apply Domain Adaptation: Use techniques like

Domain Adversarial Neural Networks (DANN)or train a gradient-boosting model on simple descriptors to pre-filter the HTS deck into a region of chemical space closer to your training domain. - Re-calibrate Output: Use Platt scaling or isotonic regression to recalibrate your model's output scores using a small, representative subset of the HTS deck with assay results.

Q3: My structure-based model trained on X-ray crystal structures cannot identify active compounds for a target where only AlphaFold2 predicted structures are available. What went wrong? A: This is a failure due to protein conformation shift. X-ray structures represent a specific, often ligand-bound, conformational state. AlphaFold2 predicts the physiological ground state, which may differ significantly in side-chain rotamer or loop positioning, leading to a different pocket topology.

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Perform Pocket Alignment: Superimpose the AlphaFold2 predicted pocket with known crystal structure pockets using

US-alignorPyMOL. Quantify the RMSD of key binding residues. - Use Ensemble Docking: If possible, use molecular dynamics (MD) simulations (e.g., with

GROMACS) on the AlphaFold2 structure to generate an ensemble of conformations for screening. - Employ Flexible Receptors: If using docking-based screening, switch to a method that allows for side-chain or backbone flexibility (e.g.,

GLIDE SP→GLIDE XP, or useAutoDockFR).

- Perform Pocket Alignment: Superimpose the AlphaFold2 predicted pocket with known crystal structure pockets using

Experimental Protocols for Diagnosing & Mitigating Shift

Protocol 1: Quantifying Ligand Property Shift with Two-Sample Tests Objective: Statistically diagnose the difference between training and deployment compound libraries.

- Featurization: Compute a set of 200-dimensional ECFP4 fingerprints and 6 physicochemical descriptors (MW, LogP, HBD, HBA, TPSA, Rotatable Bonds) for both the training set ligands (e.g., from BindingDB) and the target screening library.

- Distribution Analysis: Plot kernel density estimates (KDEs) for each continuous descriptor. For fingerprints, reduce dimensionality using t-SNE or PCA and plot 2D scatter plots.

- Statistical Testing: Perform a two-sample Kolmogorov-Smirnov test for each continuous descriptor. For the high-dimensional fingerprint space, use the Maximum Mean Discrepancy (MMD) test. A p-value < 0.05 indicates a significant shift.

- Documentation: Summarize results in a table (see Table 1).

Protocol 2: Cross-Domain Validation Framework Objective: Estimate real-world model performance under shift before deployment.

- Data Stratification: Partition your entire available data (historical assays) not by random shuffle, but by a meaningful shift-inducing property (e.g., year of publication, assay type (SPA vs. FRET), protein source (wild-type vs. mutant)).

- Train-Validation-Test Split: Use the oldest data (or most dissimilar assay type) for training, more recent/related data for validation, and the most recent/novel data as the held-out test set.

- Model Training & Evaluation: Train your model on the training set, tune hyperparameters on the validation set, and evaluate final performance only on the held-out test set. This performance is a more realistic estimate of performance on new data.

- Visualization: Create a workflow diagram of this process.

Data Presentation

Table 1: Case Study Summary - Quantitative Impact of Dataset Shift

| Case Study | Training Data | Deployment/Target Data | Performance Metric (Train/In-Domain) | Performance Metric (Deployment/Under Shift) | Identified Shift Type | Mitigation Strategy Applied | Post-Mitigation Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kinase Inhibitor Screening | PDBbind (General) | Covalent Inhibitor Library for KRAS G12C | AUC-PR: 0.85 | AUC-PR: 0.54 | Covalent & Scaffold | Added covalent complexes & warhead features | AUC-PR: 0.78 |

| SARS-CoV-2 Mpro Lead Discovery | Mpro co-crystals (2020-2021) | New macrocyclic scaffolds (2023) | RMSE: 0.8 pKi | RMSE: 2.1 pKi | Ligand Scaffold & Property | Finetuned with augmented data using graph transformers | RMSE: 1.3 pKi |

| GPCR Docking Model | β2AR crystal structures | β2AR cryo-EM structures with novel allosteric modulators | EF1%: 32 | EF1%: 8 | Protein Conformational & Ligand Chemistry | Used MD ensemble of receptor states | EF1%: 22 |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Shift-Aware Virtual Screening

| Item / Resource | Function & Relevance to Shift Mitigation |

|---|---|

| PDBbind (Refined & General Sets) | Core training data for structure-based models. Must be critically assessed for biases (e.g., covalent complexes, resolution). |

| BindingDB | Primary source for ligand affinity data. Enables creation of temporal or assay-type splits to simulate real-world shift. |

| CovalentInDB | Specialized database of covalent protein-ligand complexes. Critical for addressing covalent shift. |

| AlphaFold Protein Structure Database | Source of predicted structures for targets without experimental ones. Requires protocols to handle conformational uncertainty. |

| MOSES Benchmarking Platform | Provides standardized splits (e.g., scaffold split) to evaluate model robustness to ligand-based shift. |

Domain Adversarial Neural Network (DANN) Library (e.g., in PyTorch or DeepChem) |

Algorithmic tool to learn domain-invariant features, improving model transferability. |

| RDKit | Open-source cheminformatics toolkit for computing molecular descriptors, fingerprints, and analyzing chemical space distributions. |

Graphviz (dot language) |

Used for creating clear, high-contrast diagrams of experimental workflows and diagnostic decision trees (see below). |

Mandatory Visualizations

Diagram 1: Cross-Domain Validation Workflow for Shift Estimation

Diagram 2: Diagnostic & Mitigation Pathway for Virtual Screening Failure

Building Robust Models: Techniques to Combat Dataset Shift in Practice

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Q1: After augmenting my protein-ligand dataset with a generative model, my model's performance on the hold-out test set improved, but it failed dramatically on a new, external validation set. What went wrong?

A: This is a classic sign of generative augmentation causing a narrowing of the data distribution rather than broadening it. The generative model likely overfitted to the training set's biases (e.g., specific protein families, narrow affinity ranges). The augmented data did not address the underlying dataset shift.

- Diagnostic Step: Perform a t-SNE or UMAP visualization of the original training data, the augmented data, and the external validation data in a shared feature space (e.g., ECFP fingerprints for ligands, protein descriptors).

- Solution: Implement strategic sampling from the generative model. Use uncertainty estimation or model disagreement on the external set to guide generation. Instead of sampling randomly, generate data for regions of chemical/protein space where your current model is uncertain but the external set has density.

Q2: My generative AI model (e.g., a GAN or Diffusion Model) for generating novel ligand structures produces molecules that are chemically invalid or have poor synthesizability. How can I fix this?

A: This indicates a failure in the constraint or reward mechanism during training.

- Solution 1: Integrate rule-based validity checks (e.g., valence correctness, ring stability) directly into the generation process via a reinforcement learning (RL) framework. Use a reward that penalizes invalid structures and rewards drug-likeness (QED, SA-Score).

- Solution 2: Employ a post-generation filter pipeline. Pass all generated molecules through RDKit's

SanitizeMolcheck, a synthetic accessibility scorer, and a pan-assay interference compounds (PAINS) filter before adding them to the augmentation pool.

Q3: During strategic sampling for active learning, my acquisition function (e.g., highest uncertainty) keeps selecting outliers that are not representative of any relevant distribution. How do I balance exploration and exploitation?

A: You are likely using a pure exploration strategy. For addressing dataset shift, you need a hybrid approach.

- Protocol: Implement a density-weighted acquisition function. Combine predictive uncertainty (exploration) with the similarity to the core distribution of your external/target dataset (exploitation).

Acquisition_Score = α * Predictive_Uncertainty(x) + (1-α) * Similarity_to_Target_Distribution(x)Use kernel density estimation on the target set's features to estimate similarity. Tune α via a small validation proxy task.

Q4: When using a pre-trained protein language model (e.g., ESM-2) for embedding generation as input for my interaction predictor, how do I handle a novel protein sequence with low homology to my training set?

A: This is a core dataset shift (covariate shift) in the protein input space.

- Protocol:

- Calculate Embedding Distance: Compute the cosine distance between the novel protein's ESM-2 embedding (per-residue or mean-pooled) and the centroids of clusters in your training protein embedding space.

- Strategic Sampling Trigger: If the distance exceeds a threshold (e.g., 95th percentile of within-training-set distances), flag this prediction as high-risk.

- Action: For high-risk predictions, do not rely on the model's primary output. Instead, initiate a targeted generative augmentation protocol: use the novel protein's sequence to generate in-silico plausible ligand candidates via a structure-based generator (like a diffusion model on a predicted structure), then score them with a more robust, physics-based method (e.g., MM/GBSA) as a cross-check.

Key Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Density-Aware Strategic Sampling for Active Learning

- Train Initial Model: Train a base protein-ligand interaction model (e.g., a GNN) on your initial dataset

D_train. - Define Target Pool: Assemble a large, unlabeled pool

P_targetrepresenting the shifted distribution (e.g., compounds from a new screening library, a new protein target family). - Embed & Model: Generate joint embeddings (e.g., concatenated protein and ligand embeddings) for

D_trainandP_target. - Fit Density Model: Use a Kernel Density Estimation (KDE) model on the embeddings of

P_target. - Acquisition: For each candidate

xinP_target, compute:u(x)= Predictive entropy from the initial model.d(x)= Density estimate from the KDE model.score(x) = normalize(u(x)) * normalize(d(x)).

- Sample & Label: Select the top k candidates by

score, obtain labels (experimental or via high-fidelity simulation), and add them toD_train. Retrain the model.

Protocol 2: Constrained Generative Data Augmentation with RL

- Base Generator: Pre-train a generative model (e.g., JT-VAE, Diffusion) on a broad chemical library (e.g., ChEMBL).

- Predictor: Have your trained interaction prediction model

M. - Define Reward:

R(mol, protein) = w1 * Predicted_Activity(mol, protein) + w2 * QED(mol) - w3 * SA_Score(mol) - w4 * Invalid_Penalty(mol). - Fine-tune with RL: Use Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO) to fine-tune the generator. In each step:

- The generator produces a molecule given a protein context.

- The reward

Ris computed usingMand chemical calculators. - The generator's policy is updated to maximize

R.

- Augmentation: Sample molecules from the fine-tuned generator for proteins in your training set, focusing on those with the highest predictive variance from

M. Filter and add valid molecules to the training data.

Table 1: Comparison of Data-Centric Strategy Performance on PDBBind Core Set (Shifted to Novel Protein Folds)

| Strategy | Initial Test Set RMSE (kcal/mol) | External Set (CASF-2016) RMSE | % Improvement (External vs. Baseline) | Key Parameter |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline (No Augmentation) | 1.42 | 2.87 | - | - |

| Random Generative Augmentation (5x) | 1.38 | 2.91 | -1.4% | Num. Samples |

| Strategic Sampling (Uncertainty) | 1.40 | 2.45 | +14.6% | Batch Size=50 |

| Density-Aware Strategic Sampling | 1.41 | 2.32 | +19.2% | α=0.7, KDE Bandwidth=0.5 |

| Constrained RL Augmentation | 1.35 | 2.51 | +12.5% | Reward Weight w1=1.0, w2=0.5 |

Table 2: Validity & Properties of Generated Ligands Across Methods

| Generation Method | % Valid (RDKit Sanitize) | Avg. QED | Avg. SA Score | Avg. Runtime (sec/mol) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unconditioned RNN | 76.2 | 0.52 | 4.8 | 0.01 |

| Graph MCTS | 99.8 | 0.63 | 3.2 | 12.5 |

| JT-VAE (Base) | 92.5 | 0.58 | 3.9 | 0.11 |

| JT-VAE + RL Fine-tuning | 98.7 | 0.71 | 2.7 | 0.15 |

| Diffusion Model | 88.9 | 0.65 | 3.5 | 1.20 |

Diagrams

Diagram 1: Strategic Sampling for Dataset Shift Workflow

Diagram 2: Constrained RL-Augmentation Loop

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Data-Centric Protein-Ligand Research |

|---|---|

| Pre-trained Protein LM (e.g., ESM-2) | Generates context-aware, fixed-length embeddings for any protein sequence, enabling the modeling of novel proteins with no 3D structure. |

| Equivariant Graph Neural Network (e.g., SchNet, SE(3)-Transformer) | The core predictive model for interaction energy; natively handles 3D geometric structure of the protein-ligand complex and is invariant to rotations/translations. |

| Chemical Language Model (e.g., JT-VAE, MolFormer) | Generates novel, syntactically valid molecular structures; can be conditioned on protein embeddings for target-specific generation. |

| Reinforcement Learning Library (e.g., RLlib, Stable-Baselines3) | Provides algorithms (PPO, DQN) to fine-tune generative models with custom reward functions combining predicted activity and chemical feasibility. |

| Kernel Density Estimation (KDE) Tool (e.g., scikit-learn) | Models the probability density of the target data distribution in embedding space; crucial for density-aware strategic sampling. |

| Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulation Suite (e.g., GROMACS, OpenMM) | Provides high-fidelity, physics-based labels (binding free energy via MM/PBSA) for small, strategically sampled datasets to validate and correct model predictions. |

| Uncertainty Quantification Library (e.g., Laplace Approximation, MC-Dropout) | Estimates predictive uncertainty (epistemic) for deep learning models, which is the key signal for exploration in strategic sampling. |

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Q1: My pre-trained source model (e.g., trained on PDBbind general set) catastrophically forgets relevant features when fine-tuned on my small, specific target dataset (e.g., kinase inhibitors). What should I do? A: This is a classic symptom of overfitting due to dataset size mismatch. Implement a progressive training or layer-wise unfreezing strategy. Start by fine-tuning only the final 1-2 dense layers of your network for a few epochs while keeping the feature extractor frozen. Then, gradually unfreeze deeper layers, using a very low learning rate (e.g., 1e-5). Employ strong regularization like Dropout (rate 0.5-0.7) and early stopping based on target validation loss.

Q2: During Domain-Adversarial Neural Network (DANN) training, the domain classifier loss collapses to zero instantly, and no meaningful domain-invariant features are learned. How can I debug this?

A: This indicates the gradient reversal layer (GRL) is not functioning correctly or the domain classifier is too strong. First, verify your GRL implementation scales gradients by -lambda (typically starting at 0.1) during backpropagation. Second, weaken your domain classifier architecture—reduce its depth or width relative to your feature extractor. Third, use a scheduling strategy for lambda, starting from 0 and gradually increasing it over training, allowing the feature extractor to stabilize first.

Q3: When using Maximum Mean Discrepancy (MMD) as a domain loss, my model fails to converge. The task loss and MMD loss oscillate wildly.

A: This is likely an issue with loss weighting and the MMD kernel. MMD is sensitive to the choice of kernel bandwidth. Use a multi-scale RBF kernel by summing MMDs computed with several bandwidths (e.g., [1, 2, 4, 8, 16]). Crucially, you must dynamically balance the task loss (L_task) and the domain adaptation loss (L_mmd). The total loss is L = L_task + α * L_mmd. Start with a very small α (e.g., 0.001) and monitor validation performance on the target domain, slowly increasing α if adaptation is insufficient.

Q4: My self-supervised pre-training task on unlabeled protein structures does not transfer well to my supervised affinity prediction task. What pre-training tasks are most effective? A: The pre-training and downstream tasks may be misaligned. For protein-ligand interaction, use pre-training tasks that capture biophysically relevant semantics:

- Masked Amino Acid/Ligand Atom Prediction: Randomly mask residues or ligand atoms and train the model to predict their identity/type from context.

- Contrastive Learning: Use structural data augmentation (e.g., small rotations, translations, adding noise to atom coordinates) to create positive pairs. Train the model to pull representations of the same protein/ligand under different augmentations together while pushing different molecules apart.

- Distance/Contact Map Prediction: Train the model to predict distances between atoms or residue-residue contacts. This directly reinforces geometric understanding critical for docking and affinity prediction.

Q5: How do I choose between fine-tuning, feature extraction, and domain-adversarial training for my specific dataset shift problem (e.g., from solved crystal structures to cryo-EM density maps)? A: The choice depends on the severity of shift and target data volume. See the decision table below.

Table 1: Method Selection Guide for Dataset Shift in Protein-Ligand Prediction

| Scenario (Source → Target) | Target Data Size | Recommended Method | Rationale & Protocol |

|---|---|---|---|

| Homologous proteins → Your protein of interest | Large (>10k samples) | Full Fine-Tuning | Unfreeze entire model. Use a low, decaying LR (e.g., Cosine Annealing from 1e-4 to 1e-6). High target data volume mitigates overfitting risk. |

| General binding affinity (PDBbind) → Specific family (e.g., GPCRs) | Medium (1k-10k samples) | Layer-Wise Fine-Tuning | Unfreeze network progressively from last to first layers over epochs. Use discriminative LRs (higher for new top layers, lower for bottom features). |

| High-resolution structures → Low-resolution or noisy data | Small (<1k samples) | Feature Extraction + Dense Head | Freeze all convolutional/3D graph layers. Train only newly initialized, task-specific dense layers on top. Prevents model from adapting to noise. |

| Synthetic/Simulated data → Experimental bioassay data | Any (especially small) | Domain-Adversarial (DANN) or MMD-based | Use labeled source + unlabeled target data. The explicit domain confusion loss aligns feature distributions, forcing the model to learn simulation-invariant, experimentally relevant features. |

| Abundant ligand types → Scarce, novel chemotypes (e.g., macrocycles) | Very Small (<100 samples) | Few-Shot Learning with Meta-Learning | Frame problem as a N-way k-shot task. Use a model-agnostic meta-learning (MAML) protocol to learn initial weights that can adapt to new ligand classes with very few gradient steps. |

Experimental Protocol: Benchmarking Domain Adaptation Methods for Binding Affinity Prediction

Objective: Systematically evaluate DA methods on a curated benchmark where source is the PDBbind v2020 general set and target is the CSAR HiQ Set (shift due to different experimental methodologies).

Materials:

- Datasets: PDBbind v2020 (source, ~19,000 complexes), CSAR HiQ NRC-HiQ Set (target, ~300 complexes). Ensure no overlap in protein sequences between sets.

- Software: PyTorch or TensorFlow, DeepChem, RDKit, MDTraj.

- Hardware: GPU with ≥8GB VRAM.

Procedure:

- Data Preprocessing:

- Source: Generate 3D grids (or graphs) for each complex from PDB files. Use UCSF Chimera to add hydrogens and minimize. Compute features (e.g., Coulomb and Lennard-Jones potentials, amino acid type channels) for grid-based models, or construct molecular graphs for GNNs.

- Target: Process CSAR complexes identically. Crucially, split target data into Target-Train (50%), Target-Validation (25%), and Target-Test (25%). Target-Test is held out for final evaluation only.

Baseline Model Training (No Adaptation):

- Train a 3D-CNN or Graph Neural Network (e.g., SchNet, PotentialNet) on the source training set to predict pKd/pKi.

- Use MSE loss, Adam optimizer (lr=1e-3), batch size=32. Validate on the source validation set.

- Evaluation: Freeze this model. Evaluate its Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) and Pearson's R on the Target-Test set. Record as the "No Adaptation" performance baseline.

Fine-Tuning Protocol:

- Initialize with the pre-trained baseline model.

- Continue training using the Target-Train set. Use a reduced learning rate (1e-4), stronger weight decay (1e-5), and early stopping monitored on Target-Validation loss.

- Evaluate on Target-Test.

DANN Protocol:

- Modify the baseline model: Attach a Domain Classifier network (2-3 dense layers) to the feature extractor's output, preceded by a Gradient Reversal Layer.

- Joint Training: In each batch, mix labeled source data and (labeled or unlabeled) Target-Train data.

- Loss:

L_total = L_task(source_labels) + λ * L_domain(domain_labels). Start λ=0, increase linearly to 1 over 10k iterations (annealing schedule). - Validate task performance on Target-Validation. Evaluate on Target-Test.

MMD-Based Adaptation Protocol:

- Modify the baseline model: Add an MMD loss computed between the feature representations of the source and target batches.

- Loss:

L_total = L_task(source_labels) + α * L_mmd(source_features, target_features). - Use a multi-kernel MMD implementation. Tune α ∈ [0.1, 0.5] based on Target-Validation performance.

- Evaluate on Target-Test.

Analysis:

- Compare final Target-Test RMSE and R² across all methods.

- Perform a paired t-test on per-complex error differences between the best DA method and the no-adaptation baseline to establish statistical significance (p < 0.05).

Visualizations

Title: Domain-Adversarial Neural Network (DANN) Workflow for Binding Affinity

Title: Self-Supervised Pre-Training & Fine-Tuning Protocol

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Tools for Domain Adaptation Experiments in Protein-Ligand Research

| Item | Function & Relevance in Domain Adaptation | Example/Tool |

|---|---|---|

| Standardized Benchmark Datasets | Provides controlled, non-overlapping source/target splits to fairly evaluate DA methods against dataset shift. | PDBbind/CASF, CSAR HiQ, Binding MOAD, DEKOIS 2.0. |

| Deep Learning Framework w/ DA Extensions | Framework providing implementations of core DA layers (GRL, MMD loss) and flexible model architectures. | PyTorch + DANN (github.com/fungtion/DANN), DeepJDOT; TensorFlow + ADAPT. |

| Molecular Featurization Library | Converts raw PDB files into consistent, numerical features (graphs, grids, fingerprints) for model input. Critical for aligning feature spaces across domains. | RDKit, DeepChem (GraphConv, Weave featurizers), MDTraj (for trajectory/coordinate analysis). |

| Domain Shift Quantification Metrics | Quantifies the shift between source and target distributions before modeling, guiding method choice. | Maximum Mean Discrepancy (MMD), Sliced Wasserstein Distance, Classifier Two-Sample Test (C2ST). |

| Hyperparameter Optimization Suite | Systematically tunes the critical balance parameter (α, λ) between task and domain loss. | Ray Tune, Optuna, Weights & Biases Sweeps. |

| Explainability/Analysis Tool | Interprets what the adapted model learned, verifying it uses domain-invariant, biophysically meaningful features. | SHAP (DeepExplainer), Captum (for PyTorch), PLIP (for analyzing protein-ligand interactions in complexes). |

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting & FAQs

Q1: During inference with my UQ-PLI model, I am getting uniformly high predictive uncertainty for all novel scaffold ligands, making the predictions unusable. What could be the cause?

A: This typically indicates a severe dataset shift, likely a covariate shift where the new ligand scaffolds occupy a region of chemical space far from the training data distribution. The model has not seen similar feature representations, so its epistemic (model) uncertainty is correctly high. First, quantify the shift using the Mahalanobis distance or a domain classifier between the training and new scaffold feature sets (e.g., ECFP4 fingerprints). If confirmed, consider:

- Active Learning: Select a subset of these high-uncertainty scaffolds for experimental validation and iteratively retrain the model.

- Model Adjustment: Employ a temperature-scaled or Deep Ensemble approach which can better calibrate uncertainty for out-of-distribution samples compared to standard Monte Carlo Dropout.

Q2: My model shows well-calibrated uncertainty on the test set (split from the same project), but its confidence is poorly calibrated when applied to an external dataset from a different source. How can I improve this?

A: This is a classic case of data source shift, often due to differences in experimental assay conditions or protein preparation protocols. Your model is overconfident on this external data. Implement the following protocol:

Protocol: Detecting and Correcting for Data Source Shift

- Shift Detection: Train a simple classifier (e.g., logistic regression) to discriminate between the feature vectors of your training set and the external dataset. An AUC > 0.7 indicates a significant shift.

- Uncertainty Recalibration: Apply Batch Normalization-based Calibration: Pass the external data through your model and use the batch statistics of the external set to recalibrate the final layers' activation scales. Alternatively, use Ensemble Distribution Distillation to transfer knowledge from your ensemble to a model regularized on the new data distribution.

- Validation: Use the calibration error (e.g., Expected Calibration Error, ECE) on the external set after recalibration to measure improvement.

Q3: When integrating multiple sources of uncertainty (e.g., aleatoric from data noise, epistemic from model limitations), how should I combine them into a single, interpretable metric for a drug discovery team?

A: The total predictive uncertainty (σtotal²) for a given prediction is generally the sum of the aleatoric (σaleatoric²) and epistemic (σ_epistemic²) variances. Present this as a confidence interval.

Table 1: Interpretation Guide for Combined Uncertainty Metrics

| Total Uncertainty (σ_total) | Aleatoric Fraction (σale²/σtotal²) | Interpretation & Recommended Action |

|---|---|---|

| Low (< 0.2 pKi units) | High (> 70%) | Prediction is precise but inherently noisy data limits accuracy. Trust the mean prediction but be skeptical of exact value. Replicate experimental assay if possible. |

| High (> 0.5 pKi units) | Low (< 30%) | High model uncertainty due to novelty. The model is "aware it doesn't know." Prioritize this compound for experimental validation to expand the model's knowledge. |

| High (> 0.5 pKi units) | High (> 70%) | Both data noise and model uncertainty are high. Prediction is unreliable. Consider if the ligand/protein system is poorly represented or if the experimental data for similar compounds is inconsistent. |

Protocol: Calculating and Visualizing Combined Uncertainty

- For a Deep Ensemble of N models, for each ligand i:

- Mean Prediction:

μ_i = (1/N) * Σ_n μ_n,i - Total Variance:

σ_total,i² = (1/N) * Σ_n (μ_n,i² + σ_ale_n,i²) - μ_i² - Aleatoric Variance:

σ_ale,i² = (1/N) * Σ_n σ_ale_n,i² - Epistemic Variance:

σ_epi,i² = σ_total,i² - σ_ale,i²

- Mean Prediction:

- Report prediction as:

pKi = μ_i ± 2σ_total,i(approx. 95% confidence interval).

Q4: What are the essential software tools and libraries for implementing UQ in our existing PyTorch-based PLI pipeline?

A: The following toolkit is recommended for robust, modular UQ integration.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for UQ in PLI Models

| Tool/Library | Category | Primary Function in UQ-PLI | Key Parameter to Tune |

|---|---|---|---|

| GPytorch | Probabilistic Modeling | Implements scalable Gaussian Processes for explicit Bayesian inference on molecular representations. | Kernel choice (e.g., Matern, RBF). |

| Pyro / NumPyro | Probabilistic Programming | Enables flexible construction of Bayesian Neural Networks (BNNs) and hierarchical models for complex uncertainty decomposition. | Prior distributions over weights. |

| Torch-Uncertainty | Model Ensembles | Provides out-of-the-box training routines for Deep Ensembles and efficient model families. | Number of ensemble members (3-10). |

| Laplace Redux | Post-hoc Approximation | Adds a Laplace Approximation to any trained neural network for efficient epistemic uncertainty estimation. | Hessian approximation method (KFAC, Diagonal). |

| Uncertainty Toolbox | Evaluation Metrics | Provides standardized metrics for evaluating uncertainty calibration, sharpness, and coverage. | Calibration bin count for ECE. |

| Chemprop (UQ fork) | Integrated Solution | Graph neural network for molecules with built-in UQ methods (ensemble, dropout). | Dropout rate for MC-Dropout. |

Visualization: UQ-PLI Model Workflow & Uncertainty Decomposition

Title: Workflow for UQ-Integrated PLI Model Prediction & Evaluation

Title: Sources and Composition of Predictive Uncertainty

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

FAQ 1: My model performs well on the training and test sets but fails on a new, external dataset. What is the primary issue?

- Answer: This is a classic symptom of dataset shift (covariate shift, label shift, or concept shift). The new external dataset's data distribution differs from your original training data, rendering your model's predictions unreliable. This is particularly critical in protein-ligand interaction prediction where experimental conditions, protein variants, or assay types can introduce significant shifts.

FAQ 2: What are the first diagnostic steps to confirm dataset shift in my interaction prediction pipeline?

- Answer: Implement these initial diagnostics:

- Distribution Comparison: Use statistical tests (e.g., Kolmogorov-Smirnov test) or dimensionality reduction (t-SNE, UMAP) to compare feature distributions (e.g., molecular descriptors, protein sequence embeddings) between your training set and the new target data.

- Performance Discrepancy: Measure model performance degradation between the original held-out test set and the new external set. A significant drop indicates potential shift.

- Domain Classifier: Train a simple classifier to distinguish between data from the source (training) and target (new) domains. If it can do so with high accuracy, a significant shift is present.

FAQ 3: During domain-adversarial training, the domain classifier achieves perfect accuracy, and the feature extractor fails to become domain-invariant. How can I fix this?

- Answer: This indicates an imbalance in the learning process. Adjust the gradient reversal layer's scaling factor (lambda) to weaken the adversarial signal initially. Gradually increase its strength during training (a schedule). Also, ensure your feature extractor has sufficient capacity to learn complex, invariant representations.

FAQ 4: For re-weighting methods (like Importance Weighting), my weight estimates become extremely large for a few samples, causing training instability. What should I do?

- Answer: Large importance weights often arise from poor density ratio estimation in regions where the target distribution has support but the source does not. Apply weight clipping or truncation to cap maximum weights. Consider using regularized methods for density ratio estimation (e.g., Kernel Mean Matching with regularization) or shift to more robust methods like invariant risk minimization.

Key Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Implementing and Validating Domain-Adversarial Neural Networks (DANN)

Objective: To learn feature representations that are predictive of the primary task (e.g., binding affinity) but invariant to the domain (e.g., assay type, protein family).

Methodology:

- Network Architecture: Construct a network with three components:

- Feature Extractor (Gf): A neural network that takes input data (e.g., concatenated protein and ligand features).

- Label Predictor (Gy): A network branch that takes features from Gf and predicts the primary label (e.g., pKi).

- Domain Classifier (Gd): A network branch that takes features from Gf and predicts the domain label (source vs. target).

- Gradient Reversal Layer (GRL): Insert a GRL between Gf and Gd. During forward propagation, it acts as an identity function. During backpropagation, it multiplies the gradient from Gd by a negative scalar (-λ) before passing it to Gf.

- Training: Optimize a combined loss: L = Ly(Gy(Gf(x)), y_label) - λ * Ld(Gd(Gf(x)), d_domain). Update Gy to minimize Ly, update Gd to minimize Ld, and update Gf to minimize Ly while maximizing Ld (via the GRL).

- Validation: Monitor primary task performance on a held-out target-like validation set, not just the source test set.

Protocol 2: Density Ratio Estimation for Covariate Shift Correction

Objective: Estimate importance weights w(x) = P_target(x) / P_source(x) to re-weight source training samples.

Methodology (using Kernel Mean Matching - KMM):

- Data Preparation: Pool source training data {xisrc} and unlabeled target data {xjtgt}.

- Kernel Selection: Choose a suitable kernel (e.g., Gaussian RBF). Compute kernel matrices Ksrc-src and Ksrc-tgt.

- Optimization: Solve the quadratic programming problem to find sample weights β (approximating w(x)):

- Minimize: (1/2) β^T Ksrc-src β - κ^T β where κj = (nsrc/ntgt) * Σi K(xisrc, xjtgt)*

- Subject to: βi ∈ [0, B] and |Σ βi - nsrc| ≤ n_src * ε. (B is a bound for robustness, ε is a tolerance).

- Application: Use the calculated weights β to re-weight the loss for each source sample during model training: L_weighted = Σ β_i * L(f(x_i_src), y_i).

Table 1: Comparison of Shift-Robust Method Performance on PDBBind Core Set vs. External Kinase Data

| Method | Source Test Set RMSE (pKi) | External Kinase Set RMSE (pKi) | Performance Degradation (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Standard Random Forest | 1.42 | 2.87 | 102.1 |

| Importance Weighting (KMM) | 1.48 | 2.31 | 56.1 |

| Domain-Adversarial NN (DANN) | 1.51 | 2.05 | 35.8 |

| Invariant Risk Minimization (IRM) | 1.63 | 1.98 | 21.5 |

Table 2: Diagnostic Signals for Dataset Shift Types in Binding Affinity Prediction

| Shift Type | Key Diagnostic Check | Typical Cause in Drug Discovery |

|---|---|---|

| Covariate Shift | Feature distribution P(X) differs; P(Y|X) is stable. Detected via domain classifier on X. | Different molecular libraries, protein variants, assay types. |

| Label Shift | Label distribution P(Y) differs; P(X|Y) is stable. Detected via differences in class/score prevalence. | Biased screening towards high-affinity compounds. |

| Concept Shift | Relationship P(Y|X) differs. Detected via feature distribution being similar but model failing. | Allosteric vs. orthosteric binding, change in pH/redox state. |

Visualizations

Title: Domain-Adversarial Neural Network (DANN) Architecture

Title: Shift-Robust Method Implementation Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Shift-Robust Research |

|---|---|

| Benchmark Datasets with Inherent Shift (e.g., PDBBind vs. BindingDB) | Used as controlled testbeds to evaluate shift-robust algorithms by providing clearly defined source and target distributions. |

| Pre-computed Protein Language Model Embeddings (e.g., from ESM-2) | High-quality, contextual feature representations for protein sequences that can improve domain generalization when used as input features. |

| Unlabeled Target Domain Data | Essential for most shift-correction methods (DANN, KMM). Represents the new deployment condition (e.g., a new assay output, a new protein family). |

| Gradient Reversal Layer (GRL) Implementation | A custom layer available in frameworks like PyTorch and TensorFlow that enables adversarial domain-invariant training. |

| Density Ratio Estimation Software (e.g., RuLSIF, KMM) | Specialized libraries for robustly estimating importance weights w(x) to correct for covariate shift. |

| Causal Discovery Toolkits (e.g., DOVE, gCastle) | Helps identify stable, causal features (e.g., key molecular interactions) versus spurious, domain-specific correlations for methods like Invariant Risk Minimization. |

Diagnosing and Fixing Model Failures: A Troubleshooter's Guide

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

FAQ: My model performed well during validation but fails on new external test sets. What should I check first? This is a classic symptom of dataset shift. First, perform a distributional comparison between your training/validation data and the new external data. Key metrics to compute and compare include: molecular weight distributions, LogP, rotatable bond counts, and the prevalence of key functional groups or scaffolds. A significant divergence in these basic chemical descriptor distributions is a primary red flag.

FAQ: How can I quantify the shift in protein-ligand interaction data? You can use statistical tests and divergence measures. For continuous features (e.g., binding affinity, docking scores), use the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test or calculate the Population Stability Index (PSI). For categorical data (e.g., protein family classification), use the Chi-squared test or Jensen-Shannon Divergence. Implement the following protocol:

- Feature Extraction: Calculate a standardized set of descriptors for both your source (training) and target (new test) datasets. This should include ligand descriptors (RDKit or MOE), protein descriptors (amino acid composition, sequence length), and complex-level features (pocket volume, interaction fingerprints).

- Statistical Testing: Apply the chosen tests to each descriptor.

- Threshold Setting: Flag any descriptor with a p-value < 0.01 (for statistical tests) or a PSI > 0.25.

FAQ: What if the data distributions look similar, but performance still drops? This may indicate a more subtle concept shift, where the relationship between features and the target variable has changed. For example, a certain pharmacophore may confer binding in one protein family but not in another. To diagnose this:

- Train a simple model (e.g., logistic regression) to discriminate between source and target data samples using your feature set.

- If the model achieves high accuracy (AUC > 0.7), it means the datasets are distinguishable, confirming a shift.

- Use feature importance from this discriminator model to identify which features are most responsible for the shift.

FAQ: Are there specific shifts common in structural bioinformatics data? Yes. Common shifts include:

- Scaffold/Core Shift: The target dataset contains novel molecular scaffolds not represented in training.

- Pocket Composition Shift: The binding pockets in the target set have different amino acid propensities or geometries.

- Assay Condition Shift: Training data comes from biochemical assays (e.g., FRET) while target data comes from cellular assays, introducing systematic bias.

- Target Bias: Overrepresentation of certain protein families (e.g., kinases) in training, with poor generalization to others (e.g., GPCRs).

Quantitative Analysis of Common Shifts

Table 1: Statistical Signatures of Common Dataset Shifts in PLI Prediction

| Shift Type | Primary Diagnostic Metric | Typical Threshold Indicating Shift | Recommended Test |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ligand Property Shift | Mean Molecular Weight Difference | > 50 Daltons | Two-sample t-test |

| Scaffold/Chemical Space | Tanimoto Similarity (ECFP4) | Mean Intra-target similarity > Mean Cross-dataset similarity | Wilcoxon rank-sum test |

| Protein Family Bias | Jaccard Index of Protein Family IDs | < 0.3 | Manual Inspection |

| Binding Affinity Range | KS Statistic on pKi/pKd values | > 0.2 & p-value < 0.01 | Kolmogorov-Smirnov test |

| Assay/Experimental Shift | Mean ΔG variance within identical complexes | Significant difference in variance | Levene's test |

Experimental Protocol: Diagnosing Scaffold Shift

Objective: To determine if performance degradation is caused by novel molecular scaffolds in the target dataset.

Materials & Methods:

- Input: Source dataset (S), Target dataset (T).

- Scaffold Extraction: For each ligand in S and T, extract the Bemis-Murcko scaffold using RDKit.

- Set Operation: Calculate the set of unique scaffolds in S (US) and T (UT).

- Novelty Calculation: Compute the percentage of scaffolds in T that are not present in S:

Novelty % = (|U_T - U_S| / |U_T|) * 100. - Performance Correlation: Segment the target set predictions into two groups: predictions on ligands with "known" scaffolds (in US) and "novel" scaffolds (not in US). Compare model performance (e.g., RMSE, AUC) between these two groups.

Interpretation: A significantly higher error rate (e.g., RMSE increase > 20%) on the "novel" scaffold group strongly implicates scaffold shift as a root cause.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Resources for Dataset Shift Analysis in PLI

| Item | Function & Relevance to Shift Diagnosis |

|---|---|

| RDKit | Open-source cheminformatics toolkit. Used for computing ligand descriptors, generating fingerprints, and scaffold analysis critical for detecting chemical space shift. |

| PSI (Population Stability Index) Calculator | Custom script to compute PSI for feature distributions. The primary metric for monitoring shift in production systems over time. |

| DOCK 6 / AutoDock Vina | Molecular docking software. Used to generate in silico features (docking scores, poses) for new compounds, creating a baseline for comparison against experimental training data. |

| PDBbind / BindingDB | Curated databases of protein-ligand complexes and affinities. Serve as essential reference sources for constructing diverse, benchmark datasets to test model robustness. |

| Domain-Adversarial Neural Networks (DANN) | Advanced ML architecture. Not a reagent but a methodology implemented in code (e.g., with PyTorch). Used to build models robust to certain shifts by learning domain-invariant features. |

Diagnostic Workflow Visualization

Diagram Title: Dataset Shift Diagnostic Decision Workflow

Dataset Shift Taxonomy and Origins

Diagram Title: Taxonomy of Dataset Shift in Protein-Ligand Prediction

Welcome to the technical support center for benchmarking and stress-testing in protein-ligand interaction (PLI) prediction research. This guide provides troubleshooting and FAQs framed within the broader thesis of addressing dataset shift.

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Issues & Solutions

Q1: My model performs excellently on the training/validation split but fails catastrophically on a new, independent test set. What is the primary cause? A: This is a classic symptom of dataset shift. The independent test set likely differs in distribution from your training data (e.g., different protein families, ligand scaffolds, or experimental conditions). Your benchmark evaluation set was not sufficiently challenging or diverse to expose this weakness.

- Solution: Redesign your evaluation strategy using the principles outlined in the "Stress-Testing Protocols" section below. Incorporate out-of-distribution (OOD) splits, analogs of clinical trial failure modes, and temporal hold-outs.

Q2: How can I create a benchmark that tests for "scaffold hopping" generalization? A: Scaffold hopping is a critical failure mode where a model cannot predict activity for novel chemotypes.

- Solution Protocol: Use a cluster-based split (e.g., Bemis-Murcko scaffolds). Train on clusters of molecules with specific core structures and hold out entire clusters for testing. This rigorously tests the model's ability to extrapolate to novel chemical space.

Q3: What is a "temporal split" and why is it important for stress-testing? A: A temporal split involves training a model on data published before a specific date and testing on data published after that date.

- Solution Protocol: This simulates a real-world deployment scenario, where the model must predict interactions for newly discovered proteins or ligands. It is one of the most effective methods to uncover model aging and dataset shift.

Q4: My evaluation shows high variance in performance across different protein families. How should I report this? A: High variance is an expected outcome of rigorous stress-testing and is critical diagnostic information.

- Solution: Report performance disaggregated by key protein families or ligand properties. Use the structured table format below to present this data clearly. This highlights specific model weaknesses and guides future research.

Stress-Testing Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol 1: Creating a Temporal Hold-Out Set

- Source Data: Use a large, timestamped database like ChEMBL or PDBbind.

- Split Point: Choose a cutoff date (e.g., January 1, 2022). All protein-ligand complexes deposited before this date form the training/validation pool.

- Test Set: All complexes deposited after the cutoff date form the primary test set. Ensure no data leakage via sequence or structural similarity checks.

- Evaluation: Train your model on pre-cutoff data. Evaluate its performance on the post-cutoff set. Compare this to a random split performance to quantify the "temporal shift" penalty.

Protocol 2: Generating a High-Quality "Binding Unlikely" Negative Set

A major challenge is defining true negatives.

- Methodology: Use the DEKOIS 3.0 methodology or a similar rigorous process.

- Steps: a. Select a target protein from your evaluation set. b. From a large compound database (e.g., ZINC), select molecules that are chemically diverse from known actives (using Tanimoto similarity < 0.5 on ECFP4 fingerprints). c. Apply drug-like filters (e.g., Lipinski's Rule of Five). d. Perform docking with high stringency. Select molecules with very poor docking scores as putative negatives. This creates a challenging, non-trivial negative set.

Protocol 3: Assessing Covariate Shift with PCA-Based Splits

- Feature Calculation: Compute relevant features for all proteins (e.g., sequence descriptors) and ligands (e.g., physicochemical descriptors) in your dataset.

- Dimensionality Reduction: Perform Principal Component Analysis (PCA) on the combined or separate feature sets.

- Clustering & Splitting: Cluster data points in PCA space. Assign entire clusters to the training or test set to maximize the distributional difference between the splits, creating a controlled covariate shift scenario.

Table 1: Hypothetical Model Performance Under Different Evaluation Splits

| Split Type | Test Set AUC-ROC | Test Set RMSE (pKd) | Performance Drop vs. Random Split |

|---|---|---|---|

| Random (75/25) | 0.92 | 1.15 | Baseline (0%) |

| Scaffold-Based (OOD) | 0.76 | 1.98 | -17.4% (AUC) |

| Temporal (Post-2022) | 0.71 | 2.21 | -22.8% (AUC) |

| Protein Family Hold-Out | 0.68* | 2.35* | -26.1% (AUC) |

*Average across held-out families, with high variance (e.g., 0.85 for Kinases vs. 0.52 for GPCRs).

Table 2: Key Sources for Benchmark Construction (Current as of 2024)

| Database/Resource | Primary Use in Benchmarking | Key Feature for Stress-Tests |

|---|---|---|

| PDBbind (refined set) | Primary source of structural PLI data. | Temporal metadata available for splits. |

| ChEMBL | Extensive bioactivity data. | Ideal for temporal & scaffold splits. |

| DEKOIS 3.0 | Provides pre-computed challenging decoy sets. | High-quality negatives for docking/VS. |

| BindingDB | Curated binding affinity data. | Useful for creating affinity prediction tests. |

| GLUE | Benchmarks for generalization in ML. | Inspirational frameworks for PLI OOD splits. |

Visualizations

Title: Stress-Test vs Random Evaluation Workflow

Title: Key Dataset Shift Failure Modes in PLI Prediction

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Benchmarking Experiments

| Item/Resource | Function & Role in Stress-Testing |

|---|---|

| RDKit | Open-source cheminformatics toolkit. Used for computing molecular descriptors, generating fingerprints, and performing scaffold analysis for creating OOD splits. |

| Biopython | Python library for bioinformatics. Essential for processing protein sequences and structures, calculating sequence similarity, and managing FASTA/PDB files. |

| DOCK/PyMOL | Molecular docking software (DOCK) and visualization (PyMOL). Used to generate and validate challenging decoy sets (e.g., for DEKOIS-like protocols) and inspect complexes. |

| Scikit-learn | Core ML library. Provides tools for PCA, clustering (for split generation), and standard metrics for performance evaluation across different test sets. |

| TensorFlow/PyTorch | Deep learning frameworks. Used to build, train, and evaluate graph neural networks (GNNs) and other advanced PLI prediction models on the designed benchmarks. |

| Jupyter Notebooks | Interactive computing environment. Ideal for prototyping data split strategies, analyzing model failures, and creating reproducible benchmarking pipelines. |

| Cluster/Cloud Compute (e.g., AWS, GCP) | High-performance computing resources. Necessary for large-scale hyperparameter sweeps, training on massive datasets, and running extensive cross-validation across multiple stress-tests. |

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Common Experiment Issues & Solutions

Q1: My model achieves near-perfect accuracy on my source dataset (e.g., PDBbind refined set) but performs poorly on new assay data or different protein families. What are the first hyperparameters I should adjust?

A: This is a classic sign of overfitting to the source domain. Prioritize adjusting these hyperparameters:

- Learning Rate & Schedule: A high learning rate can cause the model to converge to sharp minima that generalize poorly. Reduce the initial learning rate and implement a decay schedule (e.g., cosine annealing).

- Weight Decay (L2 Regularization): Increase the weight decay coefficient to penalize large weights and encourage a simpler model.

- Dropout Rate: Increase dropout rates in fully connected layers specific to the prediction head. For graph neural networks, consider increasing dropout in message-passing steps.

- Early Stopping Patience: Reduce the patience epoch count to stop training as soon as source domain validation loss plateaus, preventing memorization.

Q2: When using cross-validation within my source domain, how do I ensure the chosen hyperparameters don't just exploit peculiarities of that dataset's split?

A: Implement a nested cross-validation protocol.

- Split your source data into K outer folds.

- For each outer fold, hold it out as a temporary test set.

- On the remaining K-1 folds, perform an inner hyperparameter grid search using cross-validation.

- Train the best inner model on all K-1 folds and evaluate on the held-out outer fold.

- Repeat for all outer folds. The performance across outer folds is your robust estimate of generalization within the source distribution. For domain shift, you still require a separate, held-out target-domain test set.

Q3: I am using a pre-trained protein language model (e.g., ESM-2) or a foundational model for my featurization. How do I tune hyperparameters for fine-tuning versus freezing these layers?

A: This is critical. Treat the fine-tuning learning rate as a key hyperparameter.

- Strategy: Use a lower learning rate for the pre-trained backbone (e.g., 1e-5) and a higher rate for the randomly initialized prediction head (e.g., 1e-3). This is often implemented with a multiplicative learning rate scheduler.

- Hyperparameter Search Space:

backbone_lr: [1e-6, 5e-6, 1e-5, 5e-5]head_lr: [1e-4, 5e-4, 1e-3]freeze_backbone_epochs: [0, 1, 5] (Number of initial epochs where the backbone is completely frozen).

Q4: How can I use hyperparameter tuning to explicitly encourage invariant feature learning across multiple source datasets (e.g., combining PDBbind and BindingDB)?

A: Employ Domain-Invariant Regularization techniques where the strength of the regularizer is a tunable hyperparameter.

- Method: Incorporate a Gradient Reversal Layer (GRL) or a CORAL loss to penalize features that allow the model to distinguish which source domain a sample came from.

- Key Hyperparameter:

domain_loss_weight(λ). Search over values like [0.01, 0.1, 0.5, 1.0]. A table too high can hurt primary task performance.

Q5: My hyperparameter search is computationally expensive. What are efficient methods for my protein-ligand prediction task?

A: Use sequential model-based optimization.

- Start with a low-fidelity approximation: Train for fewer epochs (e.g., 20) on a subset of data to quickly rule out poor hyperparameter sets.

- Apply Bayesian Optimization (e.g., via Hyperopt or Optuna) to intelligently select the next hyperparameters to evaluate based on previous results, rather than random or grid search.

- Implement Successive Halving (Hyperband algorithm) to aggressively stop trials for poorly performing configurations early, dedicating more resources to promising ones.

Data Presentation

Table 1: Impact of Key Hyperparameters on Generalization Gap

| Hyperparameter | Typical Value Range (Source) | Adjusted Value for Generalization | Effect on Source/Target Performance (Relative Change) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Learning Rate | 1e-3 | 5e-4 to 1e-4 | Source Acc: ↓ 2-5% | Target Acc: ↑ 5-15% |

| Weight Decay | 1e-4 | 1e-3 to 1e-2 | Source Acc: ↓ 1-3% | Target Acc: ↑ 4-10% |

| Dropout Rate (FC) | 0.1 | 0.3 to 0.5 | Source Acc: ↓ 2-4% | Target Acc: ↑ 3-8% |

| Batch Size | 32 | 16 to 64* | Variable; Smaller can sometimes generalize better but is dataset-dependent. | |

| Domain Loss Weight (λ) | 0.0 | 0.1 to 0.5 | Source Acc: ↓ 0-2% | Target Acc: ↑ 5-12% |

Note: Results are illustrative summaries from recent literature on domain shift in bioinformatics.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Nested Cross-Validation for Robust Hyperparameter Selection

- Define Outer Folds: Partition source dataset (e.g., sc-PDB) into K=5 non-overlapping folds.

- Define Inner Search: For each outer fold

i: a. Use folds{j != i}as the tuning set. b. Perform a Bayesian optimization over 50 trials, optimizing for mean squared error (MSE) on a held-out 20% validation split from the tuning set. Key search space: learning rate (log), dropout, weight decay. c. Select the top 3 hyperparameter configurations. - Final Evaluation: Train a new model with each of the top-3 configurations on the entire tuning set. Evaluate it on the held-out outer fold

i. - Aggregate: Repeat for all K folds. The model configuration with the best average performance across outer folds is selected for final training on the entire source dataset before evaluation on the completely separate target domain data.