Self-Driving Science: How Autonomous Platforms Like SAMPLE Are Revolutionizing Protein Engineering

Autonomous protein engineering platforms are transforming the slow, labor-intensive process of protein design into a rapid, automated, and data-driven endeavor.

Self-Driving Science: How Autonomous Platforms Like SAMPLE Are Revolutionizing Protein Engineering

Abstract

Autonomous protein engineering platforms are transforming the slow, labor-intensive process of protein design into a rapid, automated, and data-driven endeavor. This article explores the core architecture of these systems, focusing on the pioneering SAMPLE platform, which integrates artificial intelligence with robotic automation to navigate protein fitness landscapes without human intervention. We detail the methodological breakthroughs—from Bayesian optimization and protein language models to fully integrated biofoundries—that enable these platforms to achieve in weeks what traditionally took years. For researchers and drug development professionals, this review provides a comprehensive analysis of current applications, troubleshooting of experimental hurdles, validation of platform performance against traditional methods, and a forward-looking perspective on how autonomous experimentation will accelerate breakthroughs in biomedicine and therapeutic development.

The New Paradigm: Understanding Autonomous Protein Engineering

Defining Autonomous Protein Engineering Platforms

Autonomous protein engineering platforms represent a paradigm shift in biotechnology, integrating artificial intelligence (AI), robotics, and data science to create self-directed systems for designing and optimizing proteins. These platforms automate the classic Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) cycle, dramatically accelerating the process of developing enzymes and therapeutic proteins with enhanced properties such as improved catalytic activity, stability, and specificity [1]. By minimizing human intervention, they address key challenges in traditional protein engineering: the vastness of protein sequence space, the time and cost of experimental workflows, and the dependency on specialist knowledge [1] [2].

The core value of these systems lies in their ability to close the loop between computational design and experimental validation. AI models propose promising protein variants, robotic biofoundries synthesize and test them, and the resulting data are fed back to refine the AI's predictions. This creates a rapid, iterative learning cycle that efficiently navigates sequence space which is intractable for manual methods [1]. As a result, autonomous platforms are poised to drive advancements across diverse fields, from drug development and diagnostic tools to the creation of novel biocatalysts for sustainable chemistry [3] [1].

Quantitative Comparison of Representative Platforms

The table below summarizes the performance and key features of several recently developed autonomous and semi-autonomous protein engineering systems.

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Selected Autonomous Protein Engineering Platforms

| Platform / System Name | Core Technology | Reported Improvement | Timeframe | Key Innovation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| T7-ORACLE [3] | Orthogonal DNA replication in E. coli | Evolution of antibiotic resistance enzymes surviving doses 5,000x higher than wild-type. | Less than 1 week | Continuous hypermutation (100,000x normal rate) inside living cells. |

| AI-Powered Platform (iBioFAB) [1] | AI (LLM & ML) + Robotic Biofoundry | 90-fold improvement in substrate preference; 16-fold and 26-fold improvement in activity for two different enzymes. | 4 rounds over 4 weeks | End-to-end automation integrated with protein language models for generalizable application. |

| METL Framework [4] | Biophysics-based Protein Language Model | Effective design of functional GFP variants from minimal data. | N/R | Pretraining on synthetic biophysical data for superior generalization from small datasets (~64 examples). |

| COMPSS Framework [2] | Composite Computational Metrics | Improved experimental success rate by 50-150%. | N/R | A benchmarked set of metrics for reliably selecting functional, computer-generated protein sequences. |

Abbreviations: N/R: Not explicitly reported in the provided context; LLM: Large Language Model; ML: Machine Learning.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

This section outlines two foundational methodologies for autonomous protein engineering: a generalized platform for AI-driven engineering and a continuous evolution system.

Protocol: Generalized AI-Driven Enzyme Engineering on a Biofoundry

This protocol describes an end-to-end autonomous workflow for engineering enzymes, as demonstrated by the platform implemented on the Illinois Biological Foundry for Advanced Biomanufacturing (iBioFAB) [1].

1. Design Phase

- Input Requirements: Provide the wild-type protein sequence and a quantifiable assay to measure fitness (e.g., enzyme activity under specific conditions).

- Initial Library Design: Use a combination of computational models to generate a high-quality, diverse initial library of mutant sequences.

- Protein Language Model: Utilize a model like ESM-2 to predict the likelihood of amino acids at specific positions based on evolutionary context [1].

- Epistasis Model: Employ a model like EVmutation to account for synergistic effects between mutations [1].

- Curation: Combine the outputs of these models to select a library of ~180 variants for the first round of experimentation.

2. Build Phase (Automated on iBioFAB) The following modules are executed automatically by the robotic foundry:

- Module 1: Mutagenesis PCR. A HiFi-assembly based mutagenesis method is used to construct variant genes, eliminating the need for intermediate sequencing verification and ensuring >95% accuracy [1].

- Module 2: DNA Assembly. Variant genes are cloned into an appropriate expression plasmid.

- Module 3: Transformation. Plasmids are transformed into a microbial host (e.g., E. coli).

- Module 4: Colony Picking. Robotic systems pick individual colonies and inoculate cultures in deep-well plates.

- Module 5: Protein Expression. Cultures are induced to express the target protein variants.

- Module 6: Crude Lysate Preparation. Cells are lysed to release the expressed proteins for functional assays.

3. Test Phase (Automated on iBioFAB)

- Module 7: Functional Enzyme Assay. An automated, high-throughput assay (e.g., a spectrophotometric readout) is performed on the crude lysates to measure the fitness of each variant [1].

- Data Recording: All experimental data is automatically recorded and structured for the learning phase.

4. Learn Phase

- Machine Learning Model Training: The experimental data from the "Test" phase is used to train a low-N machine learning model (e.g., a Bayesian optimizer) to predict variant fitness [1].

- New Variant Proposal: The trained model proposes a new set of variants for the next DBTL cycle, focusing the search on the most promising regions of the sequence space.

5. Iteration

- The cycle (Steps 1-4) is repeated automatically. Typically, 4 rounds of iteration over 4 weeks, involving the construction and testing of fewer than 500 total variants, can yield significant improvements [1].

Protocol: Continuous Protein Evolution with T7-ORACLE

This protocol leverages the T7-ORACLE system for the continuous, accelerated evolution of proteins in E. coli [3].

1. System Setup

- Strain Preparation: Use an engineered E. coli strain that hosts the orthogonal T7 replication system.

- Plasmid Construction: Clone the gene of interest (e.g., an antibiotic resistance gene, therapeutic enzyme, or antibody fragment) into a special plasmid (replicon) that is recognized by the engineered T7 replication machinery.

- Introduce Error-Prone Polymerase: The key to the system is an engineered T7 DNA polymerase that is error-prone, introducing random mutations specifically into the target plasmid at a rate ~100,000 times higher than normal cellular replication [3].

2. Continuous Evolution Cycle

- Culture Growth: Grow the transformed E. coli cells in liquid medium.

- Mutation Generation: As the cells divide (approximately every 20 minutes), the orthogonal T7 replication system continuously replicates the target plasmid, introducing random mutations into the gene of interest with each replication cycle [3].

- Selection Pressure: Apply a selective pressure to the growing culture. For example:

- To evolve antibiotic resistance, add the antibiotic to the culture medium, gradually escalating the dose over time [3].

- For other functions, use Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting (FACS) or other selection mechanisms.

- Harvesting Variants: After multiple generations of growth under selection (e.g., less than one week), harvest the culture. The surviving population will be enriched with plasmids encoding protein variants that have evolved to function under the applied selective pressure.

3. Analysis and Validation

- Isolate plasmids from the evolved population.

- Sequence the gene of interest to identify the beneficial mutations.

- Clone and express the evolved gene variants for functional validation in a clean genetic background.

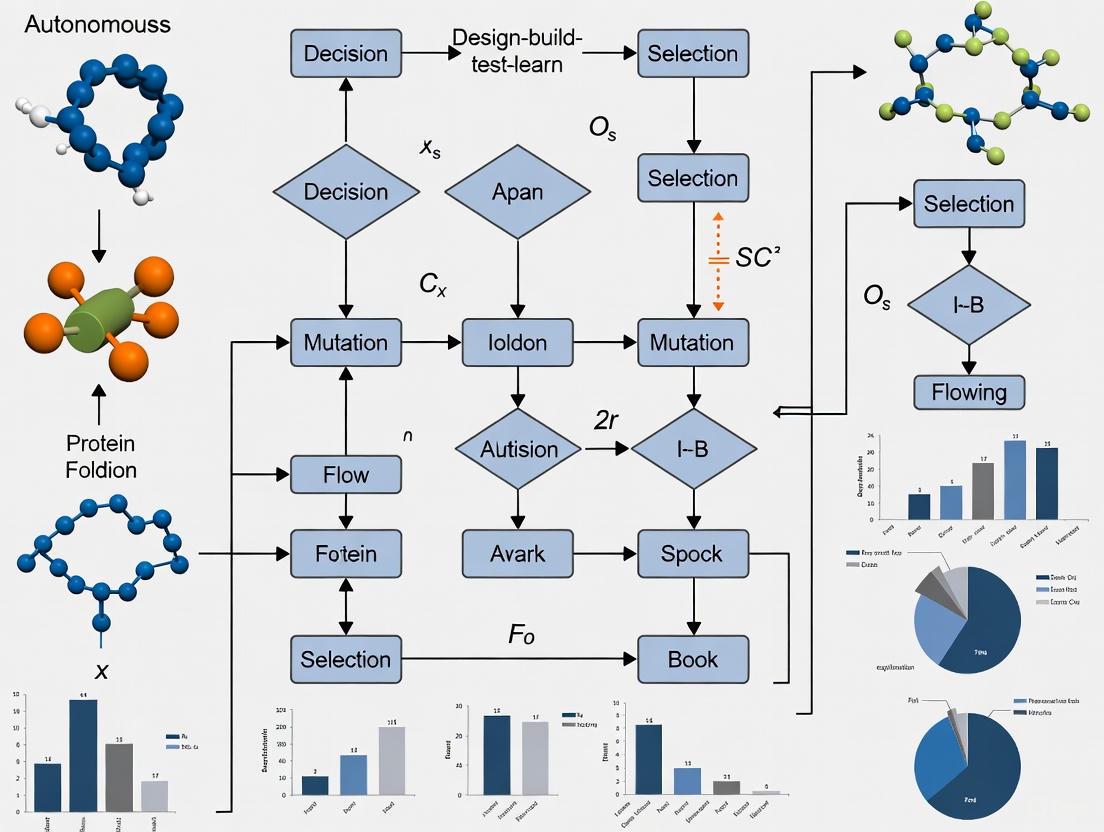

Autonomous Protein Engineering DBTL Cycle

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for Autonomous Protein Engineering

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Description | Example / Application |

|---|---|---|

| Protein Language Models (PLMs) | AI models trained on protein sequences to predict the likelihood of amino acids and infer variant fitness. | ESM-2 [1]; Used to design initial diverse variant libraries. |

| Biophysics-Based Models | AI models pretrained on molecular simulation data to capture sequence-structure-energy relationships. | METL framework [4]; Excels in prediction when experimental data is scarce. |

| Orthogonal Replication System | A separate DNA replication machinery within a host cell that mutates a target plasmid at a very high rate. | T7-ORACLE [3]; Enables continuous directed evolution in E. coli. |

| Robotic Biofoundry | An integrated suite of automated liquid handlers, incubators, and analytical instruments. | iBioFAB [1]; Executes the Build and Test phases of the DBTL cycle without human intervention. |

| Error-Prone DNA Polymerase | An engineered enzyme that introduces random mutations during DNA replication. | Engineered T7 DNA polymerase in T7-ORACLE [3]; Drives hypermutation of the target gene. |

| High-Throughput Assay | A quantifiable, automated method for measuring protein function (e.g., activity, binding). | Spectrophotometric enzyme activity assays [1]; Provides the fitness data for the Learn phase. |

| Composite Computational Metrics | A set of computed scores to filter and select generated protein sequences likely to be functional. | COMPSS framework [2]; Improves the experimental success rate by 50-150%. |

| (rac)-Exatecan Intermediate 1 | (rac)-Exatecan Intermediate 1, CAS:10298-40-5, MF:C13H13NO5, MW:263.25 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Heptadecanyl stearate | Heptadecanyl stearate, CAS:18299-82-6, MF:C35H70O2, MW:522.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Autonomous Platform Core Architecture

The field of protein engineering is undergoing a transformative shift with the advent of autonomous laboratories that seamlessly integrate artificial intelligence (AI), robotics, and data analytics. These platforms implement a closed-loop Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) cycle, where AI algorithms design protein variants, robotic systems build and test them, and the resulting data is used to learn and inform the next design cycle [5]. This integration enables the exploration of protein sequence spaces at an unprecedented scale and efficiency, moving protein engineering from a bespoke, human-dependent process to a scalable, automated science [6] [7]. The core value proposition of these platforms lies in their ability to operate with minimal human intervention, dramatically accelerating the rate of scientific discovery and application in areas such as therapeutic development, industrial biocatalysis, and renewable energy [5].

Core Architectural Framework

The architecture of an autonomous protein engineering platform is a sophisticated integration of computational and physical components. The process begins with an input protein sequence and a quantifiable fitness assay, and through iterative cycles, autonomously engineers improved proteins [6].

The Integrated Workflow Diagram

The following diagram illustrates the logical flow and component relationships within a generalized autonomous enzyme engineering platform.

Autonomous Protein Engineering DBTL Cycle

Detailed Workflow Description

Design Phase: The process is initiated by AI models that design a library of protein variants. This often involves unsupervised models like protein Large Language Models (LLMs), such as ESM-2, and epistasis models, such as EVmutation, which predict beneficial mutations based on evolutionary patterns and sequence co-dependencies without requiring prior experimental data for the target enzyme [6] [5]. These models generate a diverse and high-quality initial library, increasing the likelihood of identifying promising mutants.

Build Phase: The designed sequences are transferred to a biofoundry, such as the Illinois Biological Foundry for Advanced Biomanufacturing (iBioFAB). This phase is fully automated, handling gene synthesis, cloning, and protein expression. A key innovation is a high-fidelity mutagenesis method that achieves approximately 95% accuracy, eliminating the need for intermediate sequence verification and enabling a continuous workflow [6].

Test Phase: Robotic systems conduct high-throughput functional assays to characterize the expressed protein variants. The platform uses a quantifiable fitness measure, such as enzymatic activity under specific conditions (e.g., neutral pH), to evaluate each variant [6]. This step is modular, allowing for robust operation and easy troubleshooting.

Learn Phase: The assay data from the test phase is used to train supervised machine learning models (e.g., "low-N" regression models). These models learn the complex relationship between protein sequence and function from the experimental data and predict the next, potentially improved, set of variants to test, often by combining beneficial mutations [6] [5]. The resulting data closes the loop, informing the next Design phase.

Application Notes: Performance and Quantitative Results

The efficacy of autonomous platforms is demonstrated by their application to engineer specific enzymes with remarkable speed and efficiency. The table below summarizes key performance metrics from a landmark study that engineered two distinct enzymes in parallel.

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Autonomous Enzyme Engineering Campaigns

| Engineered Enzyme | Engineering Goal | Key Improvement | Experimental Effort | Timeframe |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arabidopsis thaliana Halide Methyltransferase (AtHMT) | Improve ethyltransferase activity and substrate preference | ~16-fold increase in ethyltransferase activity; ~90-fold shift in substrate preference [6] [5] | 4 rounds; <500 variants screened [6] | 4 weeks [6] [7] |

| Yersinia mollaretii Phytase (YmPhytase) | Enhance activity at neutral pH | ~26-fold higher specific activity at neutral pH [6] [5] | 4 rounds; <500 variants screened [6] | 4 weeks [6] [7] |

These results highlight the platform's generality—it requires only a protein sequence and a defined fitness assay—and its exceptional efficiency in navigating vast sequence spaces with minimal experimental effort [6]. In another demonstration, an industrial automated platform, iAutoEvoLab, was used for continuous evolution, successfully engineering a functional T7 RNA polymerase fusion protein with mRNA capping properties from an inactive precursor [8].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Automated Build Phase for Variant Construction

This protocol details the automated construction of plasmid DNA for protein variant expression on a biofoundry, as implemented for the engineering of AtHMT and YmPhytase [6].

- Objective: To reliably construct plasmid libraries for protein variant expression without the need for intermediate sequence verification, enabling a continuous workflow.

- Principle: A high-fidelity, HiFi-assembly based mutagenesis method is used to generate variants with high accuracy (~95%) [6].

- Materials:

- Robotic Liquid Handler: (e.g., integrated via Thermo Momentum software).

- PCR Thermocyclers.

- DpnI Restriction Enzyme: For digesting template DNA.

- E. coli Strain: For transformation.

- Omnitray LB Plates: For plating transformations.

- Procedure:

- Mutagenesis PCR Setup: The robotic liquid handler prepares PCR reactions in 96-well format using primers designed for the target mutations.

- Template Digestion: DpnI enzyme is added to the PCR product to digest the methylated template plasmid DNA.

- DNA Assembly: The digested product is used in a HiFi DNA assembly reaction.

- Transformation: The assembly reaction is transformed into competent E. coli cells via a high-throughput microbial transformation protocol.

- Plating: The transformation is plated on Omnitray LB plates with appropriate antibiotics using the robotic system.

- Colony Picking & Plasmid Purification: Colonies are automatically picked and inoculated into deep-well plates for growth, followed by automated plasmid purification.

Protocol 2: Automated Test Phase for Phytase Activity Assay

This protocol describes a high-throughput assay for measuring phytase activity at neutral pH, used to screen YmPhytase variants [6].

- Objective: To identify YmPhytase variants with enhanced activity at neutral pH.

- Principle: Phytase hydrolyzes phytic acid to release inorganic phosphate, which can be quantified colorimetrically.

- Materials:

- Assay Buffer (Neutral pH): e.g., Phosphate-buffered saline or Tris-HCl buffer, pH 7.0-7.5.

- Substrate: Phytic acid solution.

- Stop/Detection Reagent: Acidified molybdate reagent (e.g., malachite green) for phosphate detection.

- Microplate Reader: For measuring absorbance.

- Procedure:

- Lysate Preparation: In a 96-well plate, crude cell lysate containing expressed phytase variants is prepared via automated lysis.

- Reaction Initiation: The assay buffer containing phytic acid substrate is dispensed into the lysate plate to start the enzymatic reaction.

- Incubation: The reaction plate is incubated at a controlled temperature (e.g., 37°C) for a fixed time.

- Reaction Termination: The stop/detection reagent is added to quench the reaction and develop color.

- Absorbance Measurement: The plate is transferred to a microplate reader to measure absorbance at a suitable wavelength (e.g., 655 nm for malachite green).

- Data Analysis: Phosphate concentration (and thus enzyme activity) is calculated from the standard curve. Data is automatically fed into the ML model for the Learn phase.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The implementation of autonomous protein engineering relies on a suite of core reagents and computational tools. The following table catalogs essential components for establishing such a platform.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Tools for Autonomous Protein Engineering

| Item Name | Type | Function / Application |

|---|---|---|

| ESM-2 | Computational Model / Software | A protein large language model (LLM) used for zero-shot prediction of beneficial mutations based on evolutionary patterns in protein sequences [6] [5]. |

| EVmutation | Computational Model / Software | An epistasis model that identifies co-evolving residues in protein sequences to guide the design of mutant libraries with higher functional potential [6]. |

| iBioFAB | Hardware / Platform | A fully automated biofoundry that integrates robotic arms, liquid handlers, and incubators to execute the Build and Test phases of the DBTL cycle without human intervention [6] [7]. |

| HiFi DNA Assembly Mix | Laboratory Reagent | A high-fidelity enzyme mix used for seamless and accurate assembly of multiple DNA fragments, crucial for the automated construction of variant libraries [6]. |

| OrthoRep System | Molecular Biology Tool | A continuous in vivo evolution system used in some platforms (e.g., iAutoEvoLab) for growth-coupled selection and evolution of proteins over long trajectories [8]. |

| Cyclo(L-Leu-trans-4-hydroxy-L-Pro) | Cyclo(L-Leu-trans-4-hydroxy-L-Pro), CAS:115006-86-5, MF:C11H18N2O3, MW:226.27 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Azido-C6-OH | Azido-C6-OH, CAS:146292-90-2, MF:C6H13N3O, MW:143.19 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The integration of AI, robotics, and data represents a paradigm shift in protein engineering. Autonomous platforms have moved from concept to proven technology, capable of outperforming traditional methods in speed, efficiency, and scalability. By closing the DBTL loop, these systems mitigate the primary bottleneck of human-dependent design and analysis. As the underlying AI models, such as protein LLMs, become more powerful and robotic systems more accessible, the democratization and broad application of this technology across biotechnology, medicine, and sustainable chemistry is imminent. The future of protein engineering lies in self-driving laboratories that continuously and autonomously explore the frontiers of protein function.

The Self-driving Autonomous Machines for Protein Landscape Exploration (SAMPLE) platform represents a transformative approach to protein engineering that fully automates the design-test-learn cycle. This platform integrates artificial intelligence with robotic laboratory systems to navigate protein fitness landscapes without human intervention, dramatically accelerating the process of engineering proteins with enhanced properties [9]. Traditional protein engineering remains slow, labor-intensive, and inefficient, limited by human cognitive constraints and manual laboratory processes. SAMPLE addresses these limitations by creating a closed-loop system where an intelligent agent learns sequence-function relationships, designs new proteins, and experimentally tests them through automated robotics [9]. This case study examines the SAMPLE platform's application in engineering thermally stable glycoside hydrolase enzymes, detailing the methodologies, outcomes, and practical protocols that demonstrate its capabilities.

Platform Architecture & Workflow

The SAMPLE platform architecture consists of two tightly integrated components: an intelligent software agent that makes computational decisions and a fully automated physical laboratory that executes experiments.

Computational Intelligence Components

The SAMPLE agent employs Bayesian optimization (BO) as its core decision-making framework to efficiently navigate the protein sequence space. This approach is specifically designed to balance exploration of unknown regions of the fitness landscape with exploitation of promising areas already identified [9]. The agent utilizes a multi-output Gaussian process (GP) model that simultaneously predicts whether a protein sequence will be functional and estimates its thermostability (T50), effectively modeling both the continuous fitness landscape and the "holes" representing non-functional sequences [9].

Two specialized BO methods were developed to enhance sampling efficiency:

- UCB Positive Method: Considers only sequences predicted to be functional (Pactive > 0.5) and selects those with the highest Upper Confidence Bound value

- Expected UCB Method: Calculates expected UCB by multiplying the UCB value by the GP classifier's Pactive, focusing sampling on sequences that are both likely to be functional and have high predicted fitness [9]

Benchmarking on cytochrome P450 data demonstrated that these methods could identify thermostable variants with only 26 measurements on average, representing a 3-4 fold improvement over standard UCB or random sampling approaches [9].

Robotic Laboratory Integration

The physical laboratory system provides seamless experimental execution of the agent's designs. The platform implements a streamlined, general pipeline for automated gene assembly, protein expression, and biochemical characterization that takes approximately 9 hours from protein design to functional data [9]. Multiple layers of exception handling and data quality control ensure reliability: the system verifies successful gene assembly via double-stranded DNA detection, validates enzyme reaction progress curves, and confirms activity above background levels before accepting experimental results [9].

Table: SAMPLE Platform Automated Workflow Timeline

| Process Stage | Time Required | Key Operations |

|---|---|---|

| Gene Assembly | 1 hour | Golden Gate cloning of pre-synthesized DNA fragments |

| PCR Amplification | 1 hour | Expression cassette amplification with EvaGreen verification |

| Protein Expression | 3 hours | T7-based cell-free protein production |

| Thermostability Assay | 3 hours | Activity measurement across temperature gradient |

| Total Cycle Time | 9 hours | Fully automated from design to data |

SAMPLE Autonomous Control Logic: Diagram illustrating the decision flow and experimental cycle of the SAMPLE platform.

Application Case Study: Engineering Thermostable Glycoside Hydrolases

Experimental Design & Setup

The SAMPLE platform was deployed to engineer glycoside hydrolase family 1 (GH1) enzymes with enhanced thermal tolerance, a valuable property for industrial applications in biofuel production, food processing, and paper manufacturing [9]. Four independent SAMPLE agents were deployed, each starting with the same six natural GH1 sequences as initial seeds. The agents operated in a combinatorial sequence space composed of 1,352 unique GH1 sequences that incorporated natural sequence elements alongside computational designs from Rosetta and evolution-based fragments [9]. This diverse landscape ensured broad sampling of possible functional variants.

Each agent designed three new protein sequences per round based on the Expected UCB acquisition function and ran for 20 consecutive rounds without human intervention. The thermostability metric (T50) was defined as the temperature at which enzyme activity decreased by 50%, providing a robust quantitative measure for the optimization objective [9]. The experimental system demonstrated high reproducibility, with measurement errors of less than 1.6°C for T50 values across technical replicates [9].

Performance Results & Outcomes

All four SAMPLE agents successfully navigated the GH1 fitness landscape and converged on thermostable enzyme variants despite differences in their individual search trajectories. Within 20 rounds of experimentation, all agents identified enzymes with significantly enhanced thermal stability, at least 12°C higher than the starting natural sequences [9]. This improvement was achieved while searching less than 2% of the full combinatorial sequence space, demonstrating exceptional sampling efficiency [9].

The agents exhibited characteristic optimization behavior with early phases dominated by exploratory sampling to understand landscape structure, followed by progressive convergence toward fitness peaks in later rounds. Notably, the system maintained robust performance despite experimental noise and occasional instrumental challenges, with the cloud-based implementation enabling continuous operation despite physical laboratory constraints [10].

Table: SAMPLE Platform Performance Metrics

| Performance Indicator | Metric Value | Comparative Benchmark |

|---|---|---|

| Experimental Cycle Time | 9 hours | 3-4 days (manual) |

| Thermostability Improvement | ≥12°C T50 increase | Target-dependent |

| Search Space Coverage | <2% | Typically 10-20% (directed evolution) |

| Sampling Efficiency | 26 variants (average to find optima) | 3-4x better than random |

| Experimental Reproducibility | <1.6°C error | Industry standard |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Automated Gene Assembly & Verification

Principle: Generate full gene expression cassettes from pre-synthesized DNA fragments via Golden Gate cloning [9].

Procedure:

- Fragment Preparation: Dispense pre-synthesized DNA fragments (15-30bp overlapping ends) into 96-well PCR plates using liquid handling robotics

- Golden Gate Assembly:

- Combine DNA fragments with T4 DNA ligase (5U/µL) and BsaI restriction enzyme (5U/µL)

- Add 10X T4 DNA ligase buffer to 1X final concentration

- Program thermal cycler: 25 cycles of (37°C for 2 minutes, 16°C for 5 minutes)

- Final incubation: 60°C for 10 minutes, 80°C for 10 minutes

- Expression Cassette Amplification:

- Transfer 2 µL assembly reaction to 50 µL PCR mix with Q5 High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase

- Add EvaGreen fluorescent dye (1X final concentration) for real-time detection

- Amplify with standard PCR protocol: 98°C 30s; 35 cycles of (98°C 10s, 72°C 30s)

- Verification: Confirm successful amplification by monitoring EvaGreen fluorescence signal; failed reactions are flagged and sequences return to design queue

Cell-Free Protein Expression & Characterization

Principle: Directly express proteins from amplified DNA cassettes and measure thermostability via enzymatic activity [9].

Procedure:

- Cell-Free Expression:

- Combine 5 µL amplified DNA with 45 µL T7-based cell-free expression reagents

- Incubate at 30°C for 3 hours with orbital shaking (300 rpm)

- Centrifuge at 4,000 × g for 10 minutes to remove debris

- Thermostability Assay:

- Prepare 96-well PCR plate with 10 µL expressed protein per well

- Incubate plates at temperature gradient (30-80°C) for 10 minutes using thermal cycler

- Cool to 4°C, then add 90 µL substrate solution (1 mM p-nitrophenyl-glycoside in appropriate buffer)

- Monitor reaction progress at 410 nm for 30 minutes at 25°C

- Data Processing:

- Fit progress curves to determine initial reaction velocities

- Normalize activities to maximum observed velocity

- Fit temperature-activity profile to sigmoid function to calculate T50

- Flag and exclude experiments with irregular progress curves or low signal-to-noise ratios

Computational Protein Design Protocol

Principle: Employ Bayesian optimization with Gaussian process models to select protein sequences for experimental testing [9].

Procedure:

- Model Initialization:

- Encode protein sequences using a valid structural representation

- Initialize multi-output GP with radial basis function kernel

- Set hyperparameters via maximum likelihood estimation

- Sequential Design:

- Compute posterior predictive distribution for all candidate sequences

- Calculate Expected UCB scores: EUCB(x) = μ(x) + βσ(x) × Pactive(x)

- Select top 3 sequences with highest EUCB scores for experimental testing

- Set exploration parameter β to 2.0 for balanced exploration-exploitation

- Model Update:

- Incorporate new experimental data (sequence, T50, activity status)

- Retrain GP hyperparameters via gradient-based optimization

- Update internal landscape representation and uncertainty estimates

- Convergence Check:

- Monitor performance improvement over last 5 rounds

- Terminate after 20 rounds or when no improvement observed for 5 consecutive rounds

Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Research Reagents for Autonomous Protein Engineering

| Reagent / Material | Function | Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Pre-synthesized DNA Fragments | Gene assembly building blocks | 15-30bp overlapping ends, HPLC purified |

| T4 DNA Ligase | DNA fragment joining | 5U/µL, high concentration for automation |

| BsaI Restriction Enzyme | Golden Gate assembly | 5U/µL, thermostable |

| Q5 High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase | PCR amplification | Error rate: ~5 × 10â»â¶ mutations/bp |

| EvaGreen Fluorescent Dye | DNA quantification | 20X concentrate in DMSO |

| T7 Cell-Free Expression System | Protein synthesis | Pre-mixed reagents, -80°C storage |

| p-Nitrophenyl-glycoside | Enzyme activity substrate | 1 mM stock in appropriate buffer |

| 96-Well PCR Plates | Reaction vessels | Skirted, clear, automation compatible |

Visualization of Protein Fitness Landscape Navigation

Fitness Landscape Navigation: Visualization of SAMPLE agent strategies for exploring and exploiting protein fitness landscapes.

The SAMPLE platform demonstrates that fully autonomous protein engineering is not only feasible but exceptionally effective at navigating complex biological design spaces. By completing the design-test-learn cycle in just 9 hours without human intervention, SAMPLE achieves a dramatic acceleration compared to traditional manual approaches [9]. The platform's ability to efficiently explore vast sequence spaces while requiring minimal sampling highlights the power of Bayesian optimization combined with robotic automation.

This case study establishes a framework for generalized autonomous experimentation in synthetic biology and protein engineering. The methodologies detailed here can be adapted to diverse protein engineering challenges beyond thermostability, including substrate specificity, catalytic efficiency, and pH stability optimization. As autonomous platforms like SAMPLE become more accessible and robust, they promise to transform protein engineering from a specialized, labor-intensive craft into a systematic, data-driven discipline capable of addressing pressing challenges in medicine, biotechnology, and sustainable energy.

The Protein Fitness Landscape and the Challenge of Navigation

The concept of the protein fitness landscape, first introduced by Sewall Wright, provides a powerful framework for understanding the relationship between a protein's sequence and its function [11]. In this analogy, the landscape is composed of peaks and valleys, where fitness peaks represent high-performing sequences and valleys correspond to suboptimal or non-functional variants [9]. Navigating this vast, high-dimensional landscape represents one of the most significant challenges in modern protein engineering, as the number of possible sequences for a typical protein far exceeds what can be experimentally tested.

Traditional approaches to protein engineering, such as directed evolution (DE), operate as empirical hill-climbing processes on this landscape [12]. While successful for incremental improvements, these methods are inherently limited when facing epistatic interactions (non-additive effects of mutations) and rugged terrain, which can trap exploration at local optima [12]. The emergence of autonomous laboratories represents a paradigm shift, combining artificial intelligence (AI), machine learning (ML), and robotic automation to create self-driving platforms capable of navigating the fitness landscape with unprecedented efficiency [9] [5] [6]. This Application Note details the operational protocols and core components of these systems, with a specific focus on the SAMPLE platform, framing them within the broader context of autonomous protein engineering.

The Autonomous Navigation Platform: Core Architecture

Autonomous platforms for protein engineering are built upon a closed-loop Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) cycle, where intelligent agents make sequential decisions to explore and exploit the fitness landscape without human intervention. The SAMPLE (Self-driving Autonomous Machines for Protein Landscape Exploration) platform exemplifies this architecture [9].

The DBTL Cycle and SAMPLE Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the integrated, autonomous DBTL cycle as implemented in the SAMPLE platform.

- Design: The cycle begins with an intelligent agent that uses a Gaussian Process (GP) model to build a probabilistic understanding of the sequence-function relationship from limited data. To navigate the trade-off between exploring unknown regions and exploiting known promising areas, the agent employs a Bayesian Optimization (BO) strategy, such as the "Expected UCB" method, which focuses sampling on sequences predicted to be both functional and high-performing [9].

- Build: Designed protein sequences are sent to a fully automated robotic system. The SAMPLE platform, for instance, uses a streamlined pipeline of Golden Gate cloning for gene assembly, followed by PCR amplification and direct addition to cell-free protein expression systems [9].

- Test: The expressed proteins are characterized using automated, enzyme-specific biochemical assays. For thermostability engineering, the platform measures the T50 value (the temperature at which 50% of the activity is lost) with high reproducibility (error < 1.6°C) [9].

- Learn: Data from the experiments are used to update the GP model, refining the agent's internal representation of the fitness landscape. This step closes the loop, allowing the system to learn from empirical results and plan more informative experiments in the next cycle [9].

Key Experimental Protocol: Autonomous Navigation of a Glycoside Hydrolase Landscape

A specific deployment of SAMPLE involved engineering glycoside hydrolase (GH1) enzymes for enhanced thermal tolerance [9].

- Objective: To autonomously discover thermostable GH1 variants.

- Combinatorial Space: The platform searched a designed combinatorial space of 1,352 unique GH1 sequences, which introduced an average of 116 mutations compared to the starting sequences [9].

- Agent Configuration: Four independent SAMPLE agents were deployed, each seeded with the same six natural GH1 sequences.

- Execution:

- Each agent used the Expected UCB acquisition function for sequence selection.

- In each of 20 rounds, an agent selected three sequences for experimental testing.

- The fully automated Strateos Cloud Lab platform executed the build-and-test process, with a total turnaround time of approximately 9 hours from design to data [9].

- Outcome: All four agents successfully converged on thermostable enzymes that were at least 12°C more stable than the starting sequences, despite searching less than 2% of the total landscape [9]. This demonstrates the remarkable sample efficiency of the autonomous approach.

Quantitative Performance of Autonomous Platforms

The performance of autonomous platforms can be quantified by their efficiency and effectiveness in optimizing protein function. The table below summarizes key results from the SAMPLE platform and another generalized AI-powered platform.

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Autonomous Protein Engineering Platforms

| Platform / System | Target Protein | Engineering Goal | Key Experimental Result | Efficiency & Scale |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SAMPLE Platform [9] | Glycoside Hydrolase (GH1) | Enhance thermal tolerance | Variants with ≥12°C improved thermostability | 20 rounds, 4 agents, <2% of landscape searched |

| Generalized AI Platform [6] | Yersinia mollaretii Phytase (YmPhytase) | Improve activity at neutral pH | Variant with 26-fold higher specific activity | 4 weeks, 4 rounds, <500 variants tested |

| Generalized AI Platform [6] | Arabidopsis thaliana Halide Methyltransferase (AtHMT) | Improve ethyltransferase activity & substrate preference | 16-fold higher ethyltransferase activity; 90-fold shift in substrate preference | 4 weeks, 4 rounds, <500 variants tested |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Implementing an autonomous protein engineering campaign requires a suite of specialized reagents, software, and hardware. The following table details essential components as used in platforms like SAMPLE and the generalized AI platform from iBioFAB.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for Autonomous Protein Engineering

| Tool / Reagent Category | Specific Example | Function & Application |

|---|---|---|

| Machine Learning Models | Gaussian Process (GP) with Bayesian Optimization [9] | Models sequence-function relationships and decides which variants to test next in the SAMPLE platform. |

| Machine Learning Models | Protein Language Model (e.g., ESM-2) [6] | An unsupervised model used to design high-quality, diverse initial libraries based on evolutionary principles. |

| Machine Learning Models | Epistasis Model (e.g., EVmutation) [6] | Predicts the effect of mutations in the context of other mutations, helping to model non-additive effects. |

| DNA Construction & Cloning | Golden Gate Assembly [9] | A robust, automated method for assembling pre-synthesized DNA fragments into full genes. |

| DNA Construction & Cloning | High-Fidelity (HiFi) Mutagenesis [6] | A method achieving ~95% accuracy in site-directed mutagenesis, enabling continuous workflow without intermediate sequencing. |

| Protein Expression System | Cell-Free Protein Expression [9] | Allows for rapid protein synthesis directly from a DNA template, bypassing the need for cell culture. |

| Automation Hardware | Robotic Cloud Lab (e.g., Strateos) [9] | A fully integrated, remote-operated system that automates liquid handling, incubation, and assay measurements. |

| Automation Hardware | Illinois Biological Foundry (iBioFAB) [6] | An industrial-grade automated system for end-to-end execution of biological workflows, from DNA construction to assay. |

| Safety & Screening | Safety Protocol (MMSeqs2, FoldSeek) [13] | Scans designed protein sequences against databases of harmful proteins based on sequence and structural homology to mitigate risk. |

| CB-184 | CB-184, MF:C22H21Cl2NO2, MW:402.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Glimepiride sulfonamide | Glimepiride sulfonamide, CAS:119018-29-0, MF:C16H21N3O4S, MW:351.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Advanced Applications and Protocol Extensions

The principles of autonomous navigation are being extended to tackle increasingly complex challenges in protein science.

Machine Learning-Assisted Directed Evolution (MLDE)

For laboratories not yet equipped for full autonomy, ML-assisted directed evolution (MLDE) offers a powerful intermediate step. This approach uses supervised ML models trained on experimental data to predict the fitness of unsampled variants, dramatically improving the efficiency of traditional directed evolution.

A comprehensive evaluation across 16 diverse combinatorial landscapes revealed that MLDE strategies consistently matched or exceeded the performance of standard DE, with the advantage becoming more pronounced on rugged landscapes with high epistasis and fewer active variants [12]. Focused training (ftMLDE), which uses zero-shot predictors to enrich initial training sets with higher-fitness variants, was shown to further accelerate the discovery of optimal sequences [12].

Fitness Landscape Design (FLD)

A frontier in the field is the move from navigating existing landscapes to actively designing them. Fitness Landscape Design (FLD) is an inverse approach that seeks to computationally define a target fitness landscape—for example, one that suppresses the fitness of viral escape variants—and then discover molecular interventions (like antibodies) that reshape the natural landscape to match the target [11].

The FLD-with-Antibodies (FLD-A) protocol involves:

- Biophysical Modeling: Deriving a model that maps viral protein sequence to fitness based on binding affinities to host receptors and antibodies [11].

- Designability Analysis: Determining the subset of possible fitness assignments to different genotypes that is physically realizable by an antibody repertoire [11].

- Inverse Design: Using stochastic optimization to discover antibody ensembles that force viral evolution onto the user-defined, low-fitness target landscape [11].

The challenge of navigating the protein fitness landscape is being met by a new generation of autonomous platforms. By integrating intelligent agents that learn and decide with robotic systems that build and test, platforms like SAMPLE close the DBTL loop without human intervention. The resulting systems are highly efficient, as demonstrated by their ability to discover significantly improved enzymes while sampling only a tiny fraction of the possible sequence space. The protocols and tools detailed in this Application Note provide a roadmap for researchers aiming to leverage these technologies, from fully autonomous laboratories to ML-enhanced directed evolution. As the field progresses towards the active design of fitness landscapes, the potential to not only navigate but also to sculpt the evolutionary terrain itself promises to revolutionize protein engineering and therapeutic design.

Inside the Machine: AI and Automated Workflows in Action

The Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) Cycle as an Automated Loop

The Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) cycle represents the cornerstone engineering framework in synthetic biology and protein engineering. In traditional implementations, each stage requires significant human intervention, judgment, and domain expertise, creating bottlenecks that limit the pace of discovery and optimization. The emergence of autonomous experimentation systems has transformed this iterative process into a continuous, self-driving loop that dramatically accelerates protein engineering campaigns. By integrating artificial intelligence (AI), robotic automation, and biofoundry infrastructures, these platforms can execute multiple DBTL cycles with minimal human supervision, achieving in weeks what previously required months or years of manual effort [6].

This paradigm shift is particularly impactful for protein engineering, where the sequence-function landscape is vast and complex. Autonomous DBTL platforms address this challenge by combining machine learning for intelligent design, automated workstations for high-throughput construction and testing, and data analysis pipelines for rapid learning. Recent demonstrations have achieved remarkable results, including engineering enzymes with 90-fold improvement in substrate preference and 26-fold enhancement in activity at targeted pH conditions within just four weeks and fewer than 500 variants tested [6]. This document details the protocols, components, and workflows that enable such accelerated engineering in autonomous protein engineering platforms.

Core Components of an Autonomous DBTL Framework

The Integrated Workflow

Autonomous DBTL implementation requires tight integration of computational and physical components. The process begins with an input protein sequence and a quantifiable fitness objective, concluding with characterized variants and updated AI models that inform subsequent cycles [6].

Diagram 1: Autonomous DBTL Workflow for Protein Engineering

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of autonomous DBTL cycles depends on specialized reagents and materials that enable high-throughput, reproducible operations. The following table details key solutions required for automated protein engineering platforms.

Table 1: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Autonomous Protein Engineering

| Category | Specific Solution | Function in Workflow | Application Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA Construction | HiFi Assembly Mix [6] | Enables highly accurate DNA assembly without intermediate sequencing verification | Modular plasmid construction for variant libraries |

| Golden Gate Assembly with ccdB suicide gene [14] | Provides high cloning accuracy (~90%) without need for colony picking | Sequencing-free cloning in SAPP workflow | |

| Cell-Based Systems | Auto-induction Media [14] | Eliminates manual induction step in protein expression | High-throughput protein production in 96-well formats |

| OrthoRep Continuous Evolution System [8] | Enables continuous in vivo evolution with growth-coupled selection | Engineering complex protein functions | |

| Cell-Free Systems | Cell-Free Expression Lysates [15] | Rapid protein synthesis without cloning; enables toxic protein production | Megascale data generation for machine learning |

| Screening Assays | Functional Enzyme Assays [6] | Quantitatively measures variant fitness in high-throughput format | Screening methyltransferase and phytase activity |

| Analysis Tools | SEC Chromatography Analysis Software [14] | Automates analysis of thousands of chromatograms for purity, yield, oligomeric state | Standardized data output in SAPP platform |

Protocol: Implementation of an Autonomous DBTL Cycle

Stage 1: AI-Driven Protein Design

Objective

Generate a diverse, high-quality initial variant library using AI models to maximize the probability of identifying beneficial mutations while minimizing library size.

Materials

- Input protein sequence (FASTA format)

- Access to computational resources (GPU-enabled workstation or cluster)

- Protein language models (ESM-2 [6] [15] or equivalent)

- Epistasis models (EVmutation [6] or equivalent)

- Fitness prediction algorithms

Procedure

- Sequence Analysis: Input the wild-type protein sequence into the ESM-2 protein language model to calculate amino acid probabilities at each position based on evolutionary context [6].

- Epistasis Modeling: Process the same sequence through EVmutation to identify co-evolutionary patterns and epistatic interactions from homologous sequences [6].

- Variant Scoring: Combine predictions from both models to generate a ranked list of single-point mutations with predicted fitness scores.

- Library Design: Select 150-200 variants for the initial library, ensuring coverage of diverse mutation sites and types [6].

- DNA Sequence Output: Convert selected amino acid variants to DNA sequences with codon optimization for the expression host.

Technical Notes

- Balance exploration (diverse mutations) and exploitation (high-scoring mutations) in library design.

- For subsequent cycles, incorporate experimental data to train supervised machine learning models for fitness prediction [6].

- Consider structural constraints using tools like ProteinMPNN when structural data is available [15].

Stage 2: Automated Build Processes

Objective

Efficiently convert digital variant designs into physical DNA constructs and expressed proteins with minimal manual intervention.

Materials

- Oligo pools or synthesized DNA fragments

- HiFi DNA assembly master mix

- Automated liquid handling system (e.g., iBioFAB [6])

- 96-well deep-well plates

- Transformation-competent cells

- Auto-induction media [14]

Procedure

DNA Assembly Setup:

- Program liquid handler to dispense DNA fragments and assembly mix into 96-well PCR plates

- Execute HiFi assembly reaction: 50°C for 60 minutes [6]

- Perform DpnI digestion to eliminate template DNA

High-Throughput Transformation:

- Transfer assembly reactions to 96-well transformation plates containing competent cells

- Execute heat-shock transformation protocol

- Plate transformations on 8-well omnitray LB plates using robotic plating system

Culture and Expression:

- Pick colonies using automated colony picker into 96-deep well plates containing auto-induction media

- Incubate with shaking for protein expression (24-48 hours, based on target protein)

Quality Control:

- Randomly select and sequence 5-10% of variants to verify assembly accuracy (expected >95% [6])

Technical Notes

- The HiFi assembly method achieves ~95% accuracy, eliminating need for sequence verification during iterative cycles [6].

- For cost-effective DNA construction, consider DMX workflow using oligo pools and nanopore sequencing, which reduces DNA synthesis costs by 5-8 fold [14].

- Modular workflow design enables error recovery without restarting entire process.

Stage 3: High-Throughput Testing & Characterization

Objective

Rapidly quantify fitness parameters for all library variants to generate high-quality datasets for machine learning.

Materials

- Cell lysates or purified protein variants

- Microplate readers with kinetic capability

- Assay-specific substrates and reagents

- Automated liquid handling systems

- Size-exclusion chromatography (SEC) plates [14]

Procedure

Sample Preparation:

- Use robotic systems to prepare crude cell lysates from expression cultures

- Alternatively, implement automated purification (nickel-affinity and SEC) for selected variants [14]

Assay Implementation:

- Program liquid handler to dispense lysates and assay reagents into 96- or 384-well plates

- For methyltransferase activity: Measure methyltransferase or ethyltransferase activity using appropriate substrates (e.g., methyl iodide vs. ethyl iodide) [6]

- For phytase activity: Quantify phosphate release at target pH using colorimetric assay [6]

- Record kinetic measurements using plate readers

Data Collection:

- Measure fluorescence/absorbance at appropriate intervals

- Calculate enzymatic rates normalized to protein concentration or cell density

- Export data in standardized format for machine learning analysis

Technical Notes

- Implement cell-free screening systems for ultra-high-throughput (>>10,000 variants) using droplet microfluidics [15].

- SEC analysis simultaneously provides data on purity, yield, oligomeric state, and dispersity [14].

- Assay conditions should reflect final application requirements (e.g., specific pH for phytase activity [6]).

Stage 4: Machine Learning-Driven Learning

Objective

Extract meaningful patterns from experimental data to improve variant predictions in subsequent cycles.

Materials

- Experimental dataset (variant sequences and fitness measurements)

- Machine learning workstation with adequate computational resources

- ML libraries (scikit-learn, PyTorch, TensorFlow)

- Data visualization tools

Procedure

Data Preprocessing:

- Normalize fitness metrics across plates and batches

- Encode protein variants as numerical features (one-hot encoding, physicochemical properties)

- Split data into training (80%) and validation (20%) sets

Model Training:

- Train supervised machine learning models (e.g., random forest, gradient boosting, neural networks) on sequence-fitness data [6]

- For small datasets (<1000 variants), employ "low-N" machine learning methods optimized for limited data [6]

- Validate model performance using cross-validation and hold-out test sets

Variant Prediction:

- Use trained model to predict fitness of unseen variants in the sequence space

- Select top predictions for next DBTL cycle, balancing exploration and exploitation

- Generate hypotheses about sequence-function relationships

Technical Notes

- For initial cycles with limited data, combine supervised models with unsupervised protein language model predictions [6].

- Prioritize interpretable models when seeking biological insights into sequence-function relationships.

- The entire DBTL cycle should require construction and testing of fewer than 500 variants to achieve significant improvements [6].

Performance Metrics and Case Studies

Quantitative Performance of Autonomous DBTL Platforms

Recent implementations of autonomous DBTL cycles have demonstrated remarkable efficiency and efficacy in protein engineering campaigns. The following table summarizes quantitative results from published studies.

Table 2: Performance Metrics of Autonomous DBTL Platforms in Protein Engineering

| Engineering Target | Key Objective | DBTL Cycles | Timescale | Variants Tested | Performance Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arabidopsis thaliana halide methyltransferase (AtHMT) [6] | Improve ethyltransferase activity and substrate preference | 4 rounds | 4 weeks | <500 | 90-fold improvement in substrate preference; 16-fold improvement in ethyltransferase activity |

| Yersinia mollaretii phytase (YmPhytase) [6] | Enhance activity at neutral pH | 4 rounds | 4 weeks | <500 | 26-fold improvement in activity at neutral pH |

| Respiratory Syncytial Virus (RSV) neutralizer [14] | Develop multivalent antiviral proteins | 1 round (SAPP platform) | 1 week | 58 multimeric constructs | IC50 of 40 pM (dimer) and 59 pM (trimer) vs. 5.4 nM (monomer) |

| Fluorescent Protein variants [14] | Improve yield, stability, and optical properties | 1 round (SAPP platform) | 1 week | 96 variants | Identified designs with enhanced thermal stability and altered optical properties |

Emerging Paradigm: LDBT Cycle

A paradigm shift is emerging in which the Learning phase precedes Design (LDBT), leveraging large datasets and pre-trained models to make accurate zero-shot predictions [15]. This approach utilizes:

- Protein language models (ESM, ProGen) trained on evolutionary sequences [15]

- Structure-based models (ProteinMPNN, RFdiffusion) for functional design [15]

- Megascale data generation through cell-free systems and ultra-high-throughput screening [15]

This reordering potentially enables a "Design-Build-Work" model where initial designs frequently function as intended, reducing or eliminating iterative cycling [15].

The transformation of the DBTL cycle into an automated, autonomous loop represents a fundamental advancement in protein engineering methodology. By integrating AI-guided design, automated biofoundry workflows, and machine learning-driven learning, these systems achieve unprecedented efficiency in navigating complex protein sequence spaces. The protocols and case studies presented demonstrate that autonomous DBTL platforms can produce order-of-magnitude improvements in enzyme function within weeks rather than years, dramatically accelerating the development of proteins for therapeutic, industrial, and research applications. As these platforms become more accessible and standardized through frameworks like the biofoundry abstraction hierarchy [16], autonomous protein engineering is poised to become the dominant paradigm for biotechnology innovation.

Performance Benchmarks in Autonomous Platforms

The integration of Bayesian Optimization (BO) and Protein Language Models (PLMs) like ESM-2 into autonomous platforms has demonstrated remarkable efficiency and effectiveness in protein engineering campaigns. The table below summarizes quantitative outcomes from recent studies.

Table 1: Performance Metrics of AI-Driven Protein Engineering Platforms

| Platform / System | Key AI Components | Target Protein(s) | Engineering Goal | Key Quantitative Results | Experimental Scale & Duration |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PLMeAE [17] | PLM (ESM-2), Multi-layer Perceptron | tRNA synthetase (pCNF-RS) | Improve enzyme activity | - Up to 2.4-fold improvement in enzyme activity [17]. | - 4 rounds in 10 days.- 96 variants per round [17]. |

| Generalized AI Platform [6] | Protein LLM (ESM-2), Epistasis Model, Low-N ML model | Halide Methyltransferase (AtHMT) | Improve substrate preference & ethyltransferase activity | - 90-fold improvement in substrate preference.- 16-fold improvement in ethyltransferase activity [6]. | - 4 rounds over 4 weeks.- Fewer than 500 variants total [6]. |

| Generalized AI Platform [6] | Protein LLM (ESM-2), Epistasis Model, Low-N ML model | Phytase (YmPhytase) | Improve activity at neutral pH | - 26-fold improvement in activity at neutral pH [6]. | - 4 rounds over 4 weeks.- Fewer than 500 variants total [6]. |

| SAMPLE [18] | Gaussian Process Model, Bayesian Optimization | Glycoside Hydrolase (GH1) enzymes | Enhance thermal tolerance (T50) | - Identified enzymes >12 °C more stable than starting sequences.- 83% accuracy in active/inactive classification.- ~26 measurements on average to find thermostable variants in simulation [18]. | - 20 rounds of autonomous experimentation.- Searched <2% of the full sequence landscape [18]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Bayesian Optimization for Navigating Protein Fitness Landscapes

This protocol is adapted from the SAMPLE platform for the autonomous engineering of protein thermostability using Bayesian Optimization [18].

1. Problem Formulation and Agent Setup

- Define the Objective: Clearly specify the protein property to be optimized (e.g., thermostability, expressed as T50).

- Initialize the Agent: Seed the BO agent with a small set (e.g., 6) of known protein sequences and their experimentally measured fitness values.

- Configure the Model: Employ a multi-output Gaussian Process (GP) model. This model simultaneously performs two tasks:

- A classifier that predicts the probability that a given sequence is stably folded and functional (

P_active). - A regressor that predicts the continuous fitness value (e.g., T50) for sequences deemed active.

- A classifier that predicts the probability that a given sequence is stably folded and functional (

2. Iterative Design-Build-Test-Learn Cycle

- Design Phase:

- The agent uses an acquisition function to select the next sequences for experimental testing. The "Expected UCB" method is recommended [18].

- Calculation:

Expected UCB = (Predictive Mean + β * Predictive Uncertainty) * P_active, where β is a parameter balancing exploration and exploitation. - The top sequences (e.g., 3 per round) with the highest Expected UCB scores are selected for testing.

- Build Phase (Automated):

- Test Phase (Automated):

- Perform a colorimetric or fluorescent biochemical assay to measure the protein's activity.

- For thermostability (T50), measure residual activity after a heat gradient treatment and fit the data to a sigmoid curve to determine the T50 value [18].

- Implement automated data quality checks (e.g., successful PCR, valid reaction progress curves, activity above background).

- Learn Phase:

- The new sequence-fitness data is added to the training dataset.

- The multi-output GP model is retrained on this updated dataset to refine its understanding of the fitness landscape.

3. Termination

- The cycle repeats until a predefined fitness threshold is met, a set number of rounds is completed, or performance plateaus.

Protocol: Protein Language Model for Zero-Shot Variant Design

This protocol outlines the use of PLMs like ESM-2 for the initial design of protein variants, as implemented in the PLMeAE platform [17]. It consists of two modules.

Module I: Engineering Proteins Without Previously Identified Mutation Sites

- Input: The wild-type amino acid sequence.

- Procedure:

- Systematic Masking: Individually mask each amino acid position in the wild-type sequence.

- PLM Inference: For each masked position, use the PLM (e.g., ESM-2) to calculate the likelihood (probability) of all possible single-residue substitutions.

- Variant Ranking: Rank all possible single mutants based on the predicted likelihood, interpreting a higher likelihood as a proxy for higher fitness and stability.

- Candidate Selection: Select the top-ranked variants (e.g., top 96) for experimental characterization to validate the predictions and identify beneficial mutations [17].

Module II: Engineering Proteins With Known Mutation Sites

- Input: The wild-type sequence and a set of pre-defined target sites (e.g., from structural analysis or prior experiments).

- Procedure:

- Multi-site Masking: Simultaneously mask all the specified target sites in the wild-type sequence.

- Combinatorial Sampling: Use the PLM to sample or predict high-likelihood amino acid combinations across the masked positions, generating a library of multi-mutant variants.

- Library Construction: The proposed library is synthesized and tested using an automated biofoundry [17].

Workflow and System Architecture Visualization

Autonomous DBTL Cycle for Protein Engineering

The following diagram illustrates the closed-loop, autonomous Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) cycle that integrates AI and laboratory automation.

Bayesian Optimization with a Multi-Output Gaussian Process

This diagram details the Bayesian Optimization process used by the SAMPLE agent to select sequences for testing.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms for AI-Driven Protein Engineering

| Item / Platform Name | Type | Primary Function in Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| ESM-2 (Evolutionary Scale Modeling) [17] [6] | Protein Language Model (PLM) | A transformer-based model trained on millions of protein sequences. Used for zero-shot prediction of high-fitness single and multi-mutants by learning evolutionary constraints [17] [6]. |

| Gaussian Process (GP) Model [18] | Machine Learning Model | Serves as a probabilistic surrogate model in Bayesian Optimization. It models the protein fitness landscape, predicting the mean and uncertainty of fitness for unexplored sequences [18]. |

| Automated Biofoundry (e.g., iBioFAB) [6] | Robotic Laboratory System | Integrated robotic system that automates the "Build" and "Test" phases of the DBTL cycle, including DNA assembly, transformation, protein expression, and functional assays with high reproducibility [6]. |

| Cell-Free Protein Expression System [18] | Protein Synthesis Kit | Enables rapid in vitro protein synthesis without the need for cell culture, significantly speeding up the "Test" phase in platforms like SAMPLE [18]. |

| Golden Gate Cloning [18] | DNA Assembly Method | A robust and efficient DNA assembly method used in automated workflows to construct protein variant genes from pre-synthesized DNA fragments [18]. |

| ABZ-amine | ABZ-amine, CAS:80983-36-4, MF:C10H13N3S, MW:207.30 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Diclofenac Amide-13C6 | 1-(2,6-Dichlorophenyl)-2-indolinone|CAS 15362-40-0 | Research-use 1-(2,6-Dichlorophenyl)-2-indolinone, a key intermediate and impurity standard. This product is for research purposes only and is not intended for personal use. |

The advent of autonomous protein engineering platforms, such as the Self-driving Autonomous Machine for Protein Landscape Exploration (SAMPLE), represents a paradigm shift in biological design [17] [14]. These systems leverage iterative Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) cycles to navigate protein fitness landscapes with minimal human intervention. A critical physical component that enables this autonomy is the robotic biofoundry—an integrated facility that uses robotic automation and computational analytics to streamline and accelerate synthetic biology workflows [19] [20]. This application note details the core protocols and methodologies that underpin the automated gene synthesis, expression, and assaying processes within such biofoundries, providing a practical framework for their implementation in the context of advanced protein engineering research.

Automated Workflow Modules of a Robotic Biofoundry

The transition from a digital protein sequence to an empirically characterized variant is executed through a series of automated, interconnected modules. The following sections provide detailed protocols for these core operations.

Module 1: Automated DNA Construction and Clone Generation

Objective: To reliably and rapidly construct sequence-verified plasmid DNA for protein variant expression.

Background: Overcoming the DNA synthesis bottleneck is crucial for high-throughput campaigns. Traditional methods involving site-directed mutagenesis and sequence verification introduce significant delays [1]. The following protocol describes a high-fidelity assembly method that minimizes the need for intermediate sequencing.

Materials:

- Liquid Handling Robot: e.g., Integrated with the iBioFAB or similar platform [1].

- Thermal Cycler: On-deck or accessible via robotic arm.

- Microbial Transformation System: 96-well format for high-throughput.

- Plasmids: pSEVA-based backbone vectors, compatible with Golden Standard Modular Cloning (GS MoClo) or similar systems [21].

- Enzymes: High-fidelity DNA polymerase (e.g., for mutagenesis PCR), BsaI-HFv2, BbsI-HF, T4 DNA ligase [21].

- Oligonucleotides: PCR primers and synthetic gene fragments.

Procedure:

- Library Design & Primer Planning: The biofoundry's scheduling software receives a list of target variant sequences from the AI design module. Primers for PCR-based mutagenesis or DNA assembly are automatically designed and scheduled.

- Automated Mutagenesis PCR: In a 96-well plate, set up PCR reactions using a high-fidelity polymerase to amplify the plasmid template with the desired mutations. A typical reaction volume is 20 µL.

- Robotic Program: The liquid handler dispenses water, buffer, dNTPs, template DNA, primers, and polymerase into the plate. The sealed plate is transferred to the thermal cycler for amplification [1].

- DpnI Digestion & Purification: Post-PCR, add DpnI enzyme to the reaction mix to digest the methylated template DNA. Incubate for 1 hour at 37°C. The robotic system then purifies the digested PCR product using a magnetic bead-based clean-up protocol [1].

- DNA Assembly: For multi-part assemblies (e.g., constructing multi-gene circuits), use a standardized assembly method like Golden Gate Assembly.

- Reaction Setup: In a new 96-well plate, mix the purified PCR fragments (or synthesized oligos) with the appropriate backbone vector, BsaI or BbsI restriction enzyme, and T4 DNA ligase buffer and ligase.

- Cycling Conditions: Program the thermal cycler for a Golden Gate reaction (e.g., 30 cycles of 37°C for 2 minutes and 16°C for 5 minutes, followed by a final 60°C for 10 minutes) [21].

- High-Throughput Transformation: Transform the assembly reaction into chemically competent E. coli cells (e.g., NEB 10-beta or BL21(DE3)) in a 96-well format.

- Robotic Program: The liquid handler aliquots competent cells, adds the DNA assembly mix, and performs the heat-shock step. After outgrowth in SOC medium, the cells are plated onto selective LB-agar plates in 8-well Omnitrays [1].

- Colony Picking and Culture: A robotic colony picker selects individual colonies and inoculates them into deep-well 96-well plates containing liquid selective media. The plates are sealed with gas-permeable seals and incubated at 37°C with shaking for ~16 hours.

- Plasmid Purification: The liquid handler performs an alkaline lysis-based plasmid miniprep protocol on the overnight cultures to yield purified plasmid DNA, which is eluted in water or TE buffer [1]. A subset of clones may be sequenced for quality control, but the high fidelity of the assembly method (>95% accuracy) often allows this step to be bypassed in iterative cycles to save time [1].

Module 2: Automated Protein Expression and Purification

Objective: To express and purify target protein variants in a high-throughput, miniaturized format.

Background: Cell-free protein synthesis (CFPS) systems are particularly amenable to automation, enabling rapid expression freed from cell viability constraints [22]. For in vivo expression, auto-induction systems in microtiter plates streamline the process.

Materials:

- Cell-Free System: E. coli S30 extract, energy regeneration system (e.g., based on phosphoenolpyruvate or maltodextrin), amino acids, cofactors, and NTPs [22].

- Expression Host: E. coli BL21(DE3) or other suitable strains.

- Media: 2xM9 minimal medium for in vivo expression or Dynamite medium for high-density culture [21].

- Inducers: Isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG), rhamnose, arabinose, or m-toluic acid, depending on the promoter system used [21].

- Purification Resins: Nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid (Ni-NTA) agarose or other affinity resins in 96-well filter plates.

- Liquid Handler: Capable of handling 96-well deep-well plates.

Procedure:

- A. Cell-Free Protein Synthesis (CFPS) Protocol:

- Reaction Setup: On a chilled deck, the liquid handler prepares the CFPS master mix containing S30 extract, energy source, amino acids, salts, and cofactors in a 96-well plate.

- Template Addition: The purified plasmid DNA or linear PCR template from Module 1 is added to the reaction mix.

- Incubation: The plate is sealed and transferred to an incubator shaker at 30°C for 4-6 hours for protein expression [22]. The resulting lysate can often be used directly in functional assays.

- B. In Vivo Protein Expression Protocol:

- Inoculation: The liquid handler uses the purified plasmid DNA from Module 1 to transform or transform and inoculate expression hosts in a deep-well 96-well plate containing selective media.

- Growth and Induction: The plate is incubated at 37°C with shaking until the culture reaches mid-log phase (OD600 ~0.6-0.8). Induction is then performed by the automated addition of a specific inducer (e.g., 0.1-1.0 mM IPTG for the LacI/Trc system). For high-throughput, auto-induction media can be used to eliminate the need for manual induction timing [14].

- Protein Production: Post-induction, the temperature is typically reduced to 25°C, and shaking continues for 16-20 hours for optimal protein expression [21].

- Cell Harvest and Lysis: Cultures are centrifuged using a plate rotor, and the supernatant is discarded. The cell pellets are resuspended in lysis buffer and lysed by chemical or enzymatic methods (e.g., lysozyme) on the deck.

- Automated Purification (SAPP Workflow):

- Clarification: The lysate is centrifuged or filtered to remove cellular debris.

- Affinity Chromatography: The clarified lysate is transferred to a 96-well filter plate pre-loaded with Ni-NTA resin. The liquid handler performs binding, washing, and elution steps using imidazole gradients.

- Size-Exclusion Chromatography (SEC): The eluate is injected into a micro-scale SEC system. This step simultaneously purifies the protein and provides data on purity, oligomeric state, and dispersity [14]. An open-source software tool automates the analysis of thousands of SEC chromatograms.

Module 3: Automated High-Throughput Assaying

Objective: To quantitatively measure the fitness (e.g., enzymatic activity, binding affinity) of protein variants.

Background: Assays must be compatible with microtiter plate formats and yield quantitative, machine-readable data to feed the "Learn" phase of the DBTL cycle.

Materials:

- Microplate Reader: Capable of measuring absorbance, fluorescence, and/or luminescence.

- Assay Reagents: Substrates, cofactors, buffers specific to the enzyme being tested.

- Liquid Handler: For precise reagent dispensing.

Procedure:

- Assay Plate Preparation: The liquid handler transfers a small, standardized aliquot of the purified protein (from Module 2) or the CFPS reaction lysate into a 96-well or 384-well assay plate. For cell-based assays, crude cell lysates can be used directly after a lysis step [1].

- Reagent Dispensing: The assay reaction is initiated by the automated addition of the appropriate substrate and buffer.

- Example for Phytase Activity: Initiate reaction by adding phytate substrate in a buffer at the desired pH (e.g., neutral pH for engineering pH robustness) [1].

- Example for Methyltransferase Activity: Add substrate (e.g., ethyl iodide) and S-adenosyl-l-homocysteine (SAH) to measure alkyltransferase activity [1].

- Kinetic Measurement: The plate is immediately transferred to a microplate reader. The instrument continuously monitors the reaction (e.g., every 30-60 seconds for 10-30 minutes) by measuring the change in absorbance or fluorescence resulting from product formation.

- Data Processing: The raw kinetic data is automatically processed by integrated software. The initial reaction rates (V0) are calculated and normalized against protein concentration (determined by a parallel colorimetric assay like Bradford). The resulting fitness score (e.g., specific activity, improvement fold over wild-type) is compiled into a database for machine learning analysis [1] [23].

Performance Metrics and Benchmarking

The efficacy of an automated biofoundry is quantified by its throughput, speed, and success in engineering proteins. The table below summarizes performance data from recent campaigns.

Table 1: Benchmarking Performance of Automated Protein Engineering Platforms

| Platform / Study | Target Enzyme | Engineering Goal | Duration & Scale | Key Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AI-Powered Platform [1] | Halide Methyltransferase (AtHMT) | Improve substrate preference & ethyltransferase activity | 4 rounds, <500 variants | 90-fold improvement in substrate preference; 16-fold improvement in target activity |

| AI-Powered Platform [1] | Phytase (YmPhytase) | Improve activity at neutral pH | 4 rounds, <500 variants | 26-fold improvement in activity at neutral pH |

| PLMeAE [17] | tRNA synthetase (pCNF-RS) | Improve enzyme activity | 4 rounds, 10 days | Up to 2.4-fold improvement in enzyme activity |

| CAPE Challenge [23] | RhlA | Enhance catalytic activity for rhamnolipid production | 2 rounds, ~1500 variants | Best mutant production 6.16x higher than wild-type |

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table catalogs key reagents and their functions that are fundamental to operating the automated workflows described herein.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Automated Biofoundries

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| SEVA/GS MoClo Vectors [21] | Standardized, modular plasmid system for reliable DNA assembly | Facilitating rapid and combinatorial assembly of genetic circuits and expression cassettes |