RFdiffusion: Revolutionizing De Novo Protein Design with Generative AI

This article provides a comprehensive overview of RFdiffusion, a groundbreaking generative AI model that is transforming the field of de novo protein design.

RFdiffusion: Revolutionizing De Novo Protein Design with Generative AI

Abstract

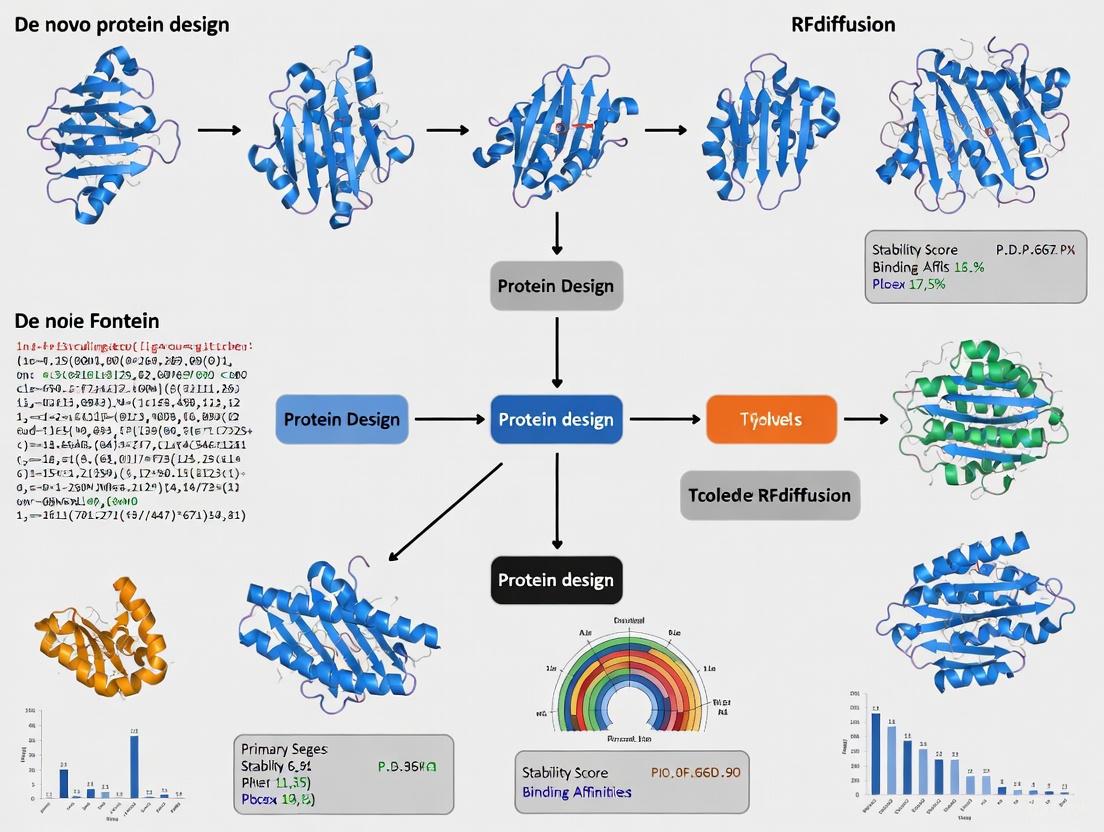

This article provides a comprehensive overview of RFdiffusion, a groundbreaking generative AI model that is transforming the field of de novo protein design. By fine-tuning the RoseTTAFold structure prediction network for denoising tasks, RFdiffusion enables the computational creation of novel protein structures and functions from simple molecular specifications. We explore the foundational principles of this diffusion-based approach, detail its methodology and diverse applications—from creating protein binders and symmetric assemblies to scaffolding enzyme active sites. The article also addresses practical challenges and optimization strategies for researchers, presents rigorous experimental validation of designed proteins, and compares performance with alternative methods. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this review synthesizes current capabilities, acknowledges limitations, and outlines future directions for this rapidly advancing technology in biomedical research and therapeutic development.

The Foundations of RFdiffusion: From Structure Prediction to Generative Design

The field of de novo protein design has been transformed by deep-learning methods, yet a general framework capable of addressing a wide range of design challenges remained elusive. RoseTTAFold, a sophisticated structure prediction network, provided a powerful foundation for understanding protein sequence-structure relationships but was not originally conceived as a generative model [1]. This application note details the conceptual and methodological genesis of adapting RoseTTAFold into RFdiffusion, a generative model for protein design that leverages denoising diffusion probabilistic models (DDPMs) to create novel protein structures and functions from simple molecular specifications [1] [2].

The core innovation lies in repurposing a network that excelled at predicting structure from sequence into one that generates novel, designable protein backbones from noise. By fine-tuning RoseTTAFold on protein structure denoising tasks, researchers obtained a generative model that achieves outstanding performance across diverse challenges, including unconditional protein monomer design, protein binder design, and symmetric oligomer design [1]. The following sections provide a detailed breakdown of the core adaptation framework, its quantitative performance, and practical experimental protocols for implementation and validation.

Core Adaptation Framework

From Structure Prediction to Generative Denoising

The adaptation strategy capitalized on key architectural properties of RoseTTAFold that made it uniquely suited for a diffusion model. Table 1 summarizes the primary modifications required to transition from a structure prediction network to a generative backbone model.

Table 1: Core Adaptations of RoseTTAFold for Generative Modeling

| Component | Function in RoseTTAFold | Adaptation for RFdiffusion | Impact on Design |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Input | Protein sequence & optional structural templates [1] | Noised protein backbone coordinates from previous diffusion step [1] | Enables iterative generation from random noise |

| Training Task | Minimize FAPE loss for structure prediction [1] | Minimize mean-squared error (MSE) loss between frame predictions and true structure [1] | Promotes global coordinate frame continuity between denoising steps |

| Network Output | Predicted protein structure from sequence [1] | Denoised structure prediction used to update input for next step [1] | Drives the generative denoising trajectory toward designable backbones |

| Conditioning | Limited to structural templates [1] | Flexible inputs (partial sequence, fixed motifs, fold info) [1] | Enables solution of diverse design challenges from molecular specifications |

The RFdiffusion model represents protein backbones using a frame representation comprising a Cα coordinate and an N-Cα-C rigid orientation for each residue [1]. Training involves corrupting structures from the Protein Data Bank (PDB) with increasing levels of Gaussian noise for up to 200 steps and tasking the network with reversing this process. The use of MSE loss, as opposed to the Frame Aligned Point Error (FAPE) loss used in structure prediction, was found to be crucial for unconditional generation, as it is not invariant to the global reference frame and thus promotes continuity between timesteps [1].

The Denoising Diffusion Workflow

The process of generating a novel protein backbone is a progressive denoising operation. Diagram 1 illustrates the logical flow and data transformation through a single denoising step within the RFdiffusion model.

Diagram 1: A single denoising step in RFdiffusion. The network takes noised residue frames as input, predicts a denoised structure, and updates the frames for the next iteration by moving in the direction of the prediction with controlled noise addition.

The generation process begins with protein backbones initialized as random residue frames. As shown in Diagram 2, the model iteratively refines these random frames over many steps. Early steps prioritize broad structural compatibility, while later steps focus on achieving highly realistic, protein-like geometries [1].

Diagram 2: The high-level generative workflow of RFdiffusion, from random initialization to a final, novel protein backbone.

A critical enhancement to the training and inference process was the implementation of self-conditioning, a strategy inspired by the "recycling" mechanism in AlphaFold2 [1]. This allows the model to condition its predictions on its own outputs from previous denoising steps, which significantly improved performance on both conditional and unconditional protein design tasks by increasing the coherence of predictions within a trajectory [1].

Performance and Validation Data

The performance of RFdiffusion was rigorously benchmarked both computationally and experimentally. A design was considered an in silico success if the AlphaFold2-predicted structure from a single sequence met three criteria: high confidence (mean pAE < 5), global backbone RMSD < 2 Ã…, and motif backbone RMSD < 1 Ã… for any scaffolded functional site [1]. This is a more stringent metric than TM-score-based assessments used in earlier studies.

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Benchmarks of RFdiffusion

| Design Challenge | In Silico Success Rate | Key Experimental Validation | Scale of Experimental Testing |

|---|---|---|---|

| Unconditional Monomer Generation | High structural diversity & confidence (AF2 pLDDT > 90) [1] | High thermostability; CD spectra match designs [1] | 9 designs (200-300 aa) characterized [1] |

| Protein Binder Design | High success rate for complex targets [1] | Cryo-EM structure nearly identical to design model (Influenza hemagglutinin binder) [1] | Hundreds of designed binders tested [1] |

| Symmetric Oligomer Design | High computational accuracy [1] | Structures confirmed by electron microscopy [1] [2] | Hundreds of symmetric assemblies tested [1] |

| Motif Scaffolding | High success on functional site scaffolding [1] | Design of metal-binding proteins & enzyme active sites [1] | Wide range of therapeutic & metal-binding proteins [1] |

The model demonstrated a remarkable ability to generalize beyond the PDB, generating elaborate structures with little overall similarity to known proteins [1]. Its performance was found to significantly outperform existing protein design methods across a broad range of problems, reducing the number of molecules that needed to be tested experimentally to as little as one per design challenge in some cases [2].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Unconditional Protein Monomer Generation

This protocol describes the procedure for generating novel protein monomers without initial structural constraints.

- Initialization: Initialize a protein chain with the desired length (L) using random residue frames (Cα coordinates and N-Cα-C orientations).

- Denoising Loop: For T timesteps (e.g., 200 steps), perform the following: a. Model Inference: Pass the current noised frames and timestep index to the RFdiffusion network. b. Prediction: The network outputs a prediction of the denoised protein structure. c. Frame Update: Update each residue frame by taking a step towards the network's prediction. Add a controlled amount of noise to generate the input for the next timestep, following the reverse of the diffusion noise schedule.

- Sequence Design: Upon completion of the denoising loop, a protein backbone is generated. Use ProteinMPNN to design sequences that encode this structure. Typically, sample 8 sequences per design [1].

- In Silico Validation: Filter designed sequences using structure prediction networks. a. Prediction: Input each designed sequence into AlphaFold2 or ESMFold to generate a predicted structure. b. Assessment: Calculate the backbone RMSD between the AF2/ESMFold prediction and the original RFdiffusion model. Also check the predicted confidence metrics (pLDDT for AF2; pAE for interface accuracy). A successful design should have a global backbone RMSD < 2 Ã… and high confidence (e.g., mean pAE < 5) [1].

Protocol 2: Functional Motif Scaffolding

This protocol details the process of scaffolding a fixed functional motif (e.g., an enzyme active site or a protein-binding peptide) within a novel protein structure.

- Motif Specification: Define the functional motif by specifying the sequence and 3D coordinates of the motif residues. These residues will be held fixed throughout the diffusion process.

- Conditional Generation: Initialize a full-length protein chain with random frames. During the denoising process, provide the fixed motif coordinates as conditioning information to the RFdiffusion network at each step.

- Progressive Scaffolding: The network learns to build a structured scaffold around the fixed motif, ensuring the overall fold is compatible and the motif is presented in its native, functional conformation.

- Sequence Design and Validation: Use ProteinMPNN for sequence design, with the motif sequence fixed. During in silico validation, ensure that the functional motif in the AF2-predicted structure is nearly identical to the original design (motif backbone RMSD < 1 Ã…), in addition to the global RMSD and confidence filters [1]. This protocol has been successfully applied to scaffold therapeutic and metal-binding motifs [1] and short peptides targeting specific proteins like Keap1 [3].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The following table lists key computational and experimental tools essential for conducting research with RFdiffusion.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for RFdiffusion-Based Design

| Reagent / Tool | Function | Application in RFdiffusion Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| RFdiffusion Software | Generative backbone model | Core engine for generating novel protein structures from noise or molecular specifications [1]. |

| RoseTTAFold Network | Structure prediction network | Provides the underlying architecture and pre-trained understanding of protein physics for the diffusion model [1]. |

| ProteinMPNN | Protein sequence design network | Designs sequences that fold into the protein backbones generated by RFdiffusion [1]. |

| AlphaFold2 / ESMFold | Protein structure prediction | In silico validation of designs; assesses whether designed sequences fold into the intended structures [1]. |

| Cryo-Electron Microscopy | High-resolution structure determination | Experimental validation of complex designs, such as symmetric assemblies and protein binders, at near-atomic resolution [1] [2]. |

| Circular Dichroism (CD) Spectroscopy | Experimental analysis of secondary structure and stability | Confirms that expressed proteins have the designed secondary structure and assesses thermostability [1]. |

| Size-Exclusion Chromatography (SEC) | Biophysical characterization | Assesses the solubility and monomeric state of expressed protein designs [4]. |

| Methyl 3-hydroxyheptadecanoate | Methyl 3-hydroxyheptadecanoate, MF:C18H36O3, MW:300.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Heparin disaccharide I-A sodium | Heparin disaccharide I-A sodium, CAS:136098-00-5, MF:C14H18NNa3O17S2, MW:605.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The adaptation of RoseTTAFold into RFdiffusion represents a paradigm shift in computational protein design. By fine-tuning a state-of-the-art structure prediction network for generative modeling within a diffusion framework, researchers have created a versatile and powerful tool that solves a wide array of design challenges. The detailed protocols and performance data outlined in this application note provide a foundation for researchers to apply and further develop these methods. The experimental success across hundreds of designs—from high-affinity binders to complex symmetric assemblies—confirms that RFdiffusion enables the design of diverse functional proteins from simple molecular specifications, opening new frontiers in therapeutic, vaccine, and nanotechnology development [1] [2].

Diffusion models have emerged as a powerful class of generative artificial intelligence that are revolutionizing de novo protein design. These models draw inspiration from statistical physics, simulating a process where noise is progressively added to data (forward diffusion) and then learning to reverse this process to generate new, structured data from noise (reverse diffusion). In computational biology, this framework has been successfully adapted to create novel protein backbone structures, enabling researchers to design proteins with specific functions and binding capabilities from scratch. The core architectural principle involves training neural networks to denoise protein representations, gradually transforming random initial states into biologically plausible and stable protein folds.

The integration of diffusion models, particularly RFdiffusion, into the de novo protein design pipeline represents a paradigm shift in computational biology. RFdiffusion uses the AlphaFold2 and RoseTTAFold2 frame representation of protein backbones comprising the Cα coordinate and N-Cα-C rigid orientation for each residue [5]. During training, a noising schedule corrupts the protein frames over multiple timesteps toward random prior distributions, with Cα coordinates corrupted with three-dimensional Gaussian noise and residue orientations with Brownian motion. The model then learns to predict the de-noised structure at each timestep, minimizing the mean squared error between the true structure and the prediction [5]. This fundamental architecture has enabled unprecedented capabilities in generating functional protein binders and antibodies with atomic-level accuracy.

Core Architectural Frameworks for Protein Backbone Generation

Coordinate-Based Diffusion (RFdiffusion)

RFdiffusion implements a coordinate-based diffusion approach that operates directly on the three-dimensional structural representation of proteins. The model represents protein backbones using frames consisting of Cα atomic coordinates and local orientational frames defined by the N-Cα-C vectors for each residue [5]. The diffusion process adds noise to both the positional (coordinates) and orientational (frames) components of the structure, with the model learning to reverse this noising process to generate novel protein structures from random noise.

The architectural implementation involves several key components. At inference time, sampling begins from a random residue distribution (XT), and RFdiffusion iteratively de-noises this initial state through a series of steps to generate novel protein structures [5]. For conditional generation tasks such as designing antibodies against specific epitopes, the framework can be fine-tuned with specialized conditioning mechanisms. The framework structure is provided as conditioning input using the template track of RFdiffusion, which represents the framework as a two-dimensional matrix of pairwise distances and dihedral angles between residue pairs [5]. This representation allows three-dimensional structures to be accurately recapitulated while maintaining global-frame invariance.

Angle-Based Diffusion (FoldingDiff)

In contrast to coordinate-based approaches, FoldingDiff employs an angle-based representation that captures protein geometry through internal coordinates rather than Cartesian coordinates. This framework represents protein backbones as a sequence of angle sets comprising three bond angles and three dihedral angles for each residue, effectively describing the relative orientation of all backbone atoms from one residue to the next [6]. This representation inherently embeds translation and rotation invariance, eliminating the need for complex equivariant neural networks.

The FoldingDiff architecture implements a denoising diffusion probabilistic model (DDPM) with a bidirectional transformer backbone that operates directly on the angular representation [6]. During generation, the model starts from random angles corresponding to an unfolded state and iteratively denoises these angles to arrive at a final folded backbone structure. A critical implementation detail involves handling the periodicity of angular values, requiring specialized noising and denoising procedures that wrap values about the domain [-π, π) [6]. This approach mirrors natural protein folding principles, where proteins twist into energetically favorable conformations through angular rotations.

Distilled and Fractional Diffusion Variants

Recent advancements have focused on optimizing the diffusion process for improved computational efficiency and modeling capability. Distilled Protein Backbone Generation explores score distillation techniques to dramatically reduce the number of sampling steps required during inference. By adapting Score identity Distillation (SiD), researchers have demonstrated that few-step generators can achieve more than a 20-fold improvement in sampling speed while maintaining comparable performance to original teacher models [7]. The key to success in this approach lies in combining multistep generation with inference-time noise modulation.

ProT-GFDM introduces fractional stochastic dynamics to protein generation, replacing standard Brownian motion with fractional processes exhibiting superdiffusive properties [8]. This architectural innovation enhances the model's ability to capture long-range dependencies in protein structures, resulting in measurable improvements across multiple quality metrics including a 7.19% increase in density, 5.66% improvement in coverage, and 1.01% reduction in Fréchet inception distance compared to conventional score-based models [8].

Table 1: Comparison of Protein Backbone Diffusion Architectures

| Architecture | Representation | Key Innovation | Performance Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| RFdiffusion [5] | Cartesian coordinates (Cα frames) | Fine-tuning for specific applications (e.g., antibodies) | Atomic-level accuracy in designed structures; experimentally validated binders |

| FoldingDiff [6] | Internal angles (6 per residue) | Rotation and translation invariance by design | Realistic angle distributions; rich secondary structure motifs |

| Distilled Diffusion [7] | Cartesian coordinates | Score identity Distillation (SiD) | 20x faster sampling; maintained designability and diversity |

| ProT-GFDM [8] | Cartesian coordinates | Fractional stochastic processes | Better long-range dependency capture; improved density and coverage |

Quantitative Analysis of Model Performance

The evaluation of diffusion models for protein backbone generation employs multiple quantitative metrics to assess the quality, diversity, and biological relevance of generated structures. Designability—the probability that a generated backbone can be realized with a stable amino acid sequence—serves as a crucial benchmark for practical utility. State-of-the-art models now achieve designability rates comparable to natural proteins, with RFdiffusion-based pipelines successfully generating functional antibodies that bind to specific epitopes with nanomolar affinity [5].

Diversity and novelty metrics ensure that models generate structurally varied proteins rather than simply memorizing training examples. Analyses confirm that designed antibodies make diverse interactions with target epitopes and differ significantly from sequences in the training dataset, with no correlation between training dataset similarity and binding success [5]. Self-consistency metrics, which measure the similarity between a designed structure and the AlphaFold2-predicted structure for its designed sequence, provide another important validation signal, though specialized versions of RoseTTAFold2 fine-tuned on antibody structures are often required for accurate assessment of antibody-antigen complexes [5].

Table 2: Key Performance Metrics for Protein Backbone Diffusion Models

| Metric Category | Specific Metrics | Typical Values for State-of-the-Art | Measurement Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Structural Quality | RMSD to native-like structures, secondary structure element composition | Similar to natural protein distributions [6] | Structural alignment, DSSP |

| Designability | Successful sequence design rate, experimental validation rate | Generation of binders with nanomolar affinity [5] | ProteinMPNN sequence design, experimental binding assays |

| Efficiency | Sampling steps, inference time | 20x speedup with distillation [7] | Computational benchmarking |

| Diversity | Structural diversity, novelty compared to training set | Significant differences from training sequences [5] | Structural clustering, sequence similarity analysis |

Experimental Protocols for Diffusion-Based Protein Design

Protocol 1: De Novo Antibody Design Using RFdiffusion

The design of de novo antibodies against specific epitopes represents one of the most significant applications of diffusion models in protein design. The following protocol outlines the key steps for generating epitope-specific antibodies using fine-tuned RFdiffusion:

Step 1: Framework Selection and Preparation

- Select an appropriate antibody framework based on the desired properties (e.g., VHH for single-domain antibodies, scFv for single-chain variable fragments)

- For VHH designs, commonly use humanized frameworks such as h-NbBcII10FGLA [5]

- Prepare the framework structure and sequence to be provided as conditioning input to RFdiffusion

Step 2: Epitope Specification and Hotspot Residue Definition

- Define the target epitope on the antigen surface

- Identify key hotspot residues that should participate in binding interactions

- Encode these hotspot residues as a one-hot feature to guide the diffusion process toward the specified epitope [5]

Step 3: Conditional Generation with RFdiffusion

- Run the fine-tuned RFdiffusion model with the framework and epitope conditioning

- The model simultaneously designs CDR loop conformations and the rigid-body placement of the antibody relative to the target [5]

- Generate thousands of candidate structures to ensure adequate sampling of the structural space

Step 4: Sequence Design with ProteinMPNN

- For each generated backbone structure, use ProteinMPNN to design complementary amino acid sequences for the CDR loops [5]

- Keep the framework sequence fixed to maintain structural stability

Step 5: In Silico Filtering with Fine-Tuned RoseTTAFold2

- Use a specialized version of RoseTTAFold2 fine-tuned on antibody structures to repredict the structure of designed antibody-antigen complexes [5]

- Filter designs based on self-consistency between the RFdiffusion design and the RoseTTAFold2 prediction

- Assess interface quality using computational metrics such as Rosetta ddG

Step 6: Experimental Validation

- Express filtered designs using high-throughput methods (yeast surface display or E. coli expression)

- Screen for binding using surface plasmon resonance (SPR) or similar techniques

- For promising binders, determine high-resolution structures using cryo-electron microscopy to verify atomic-level accuracy [5]

Protocol 2: Unconditional Backbone Generation with FoldingDiff

For unconditional generation of novel protein backbones without specific binding targets, FoldingDiff provides an angle-based approach:

Step 1: Data Preparation and Preprocessing

- Curate a dataset of protein domains (e.g., from CATH database) with lengths between 40-128 residues [6]

- Convert protein structures from Cartesian coordinates to internal angle representation

- Compute the six angles (three bond angles, three dihedral angles) for each residue

Step 2: Model Training and Configuration

- Implement a denoising diffusion probabilistic model with bidirectional transformer architecture

- Configure periodic noising and denoising procedures appropriate for angular values

- Train the model to predict the noise added at each diffusion step

Step 3: Generation and Reconstruction

- Start from random angles corresponding to an unfolded state

- Apply iterative denoising for T steps (typically 1000) to generate novel angle sets

- Convert the generated angles back to 3D Cartesian coordinates using iterative reconstruction

- Apply structural relaxation to resolve potential atomic clashes

Step 4: Quality Assessment and Filtering

- Evaluate generated structures for realistic angle distributions compared to natural proteins

- Assess structural plausibility using metrics such as Ramachandran plot preferences

- Filter designs based on structural novelty and foldability metrics

Visualization of Key Workflows

Diagram 1: FoldingDiff Angle-Based Generation

Diagram 2: RFdiffusion Antibody Design Pipeline

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Reagent/Tool | Type | Function in Protocol | Implementation Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| RFdiffusion [5] | Software | Conditional generation of protein structures | Fine-tuned on antibody complexes for epitope-specific design |

| FoldingDiff [6] | Software | Angle-based backbone generation | Uses transformer architecture; rotation-invariant by design |

| ProteinMPNN [5] | Software | Sequence design for generated backbones | Designs amino acid sequences compatible with backbone structures |

| RoseTTAFold2 [5] | Software | Structure prediction and design validation | Fine-tuned version for antibody complex prediction |

| Yeast Surface Display [5] | Experimental platform | High-throughput screening of designed binders | Enables screening of thousands of designs in parallel |

| OrthoRep [5] | Experimental system | In vivo affinity maturation | Enables evolution of binders to single-digit nanomolar affinity |

The integration of self-conditioning and specialized fine-tuning strategies has been pivotal in transforming RFdiffusion from a general protein structure prediction network into a powerful generative model for de novo protein design. These training innovations enable the solution of diverse design challenges—from unconditional protein monomer generation to the atomically accurate design of antibodies—by providing greater control over the generative process and enhancing the quality and reliability of designed proteins [1]. By building upon the deep understanding of protein structure embedded in pre-trained RoseTTAFold (RF) weights, these methods allow RFdiffusion to generate functional proteins that explore regions of the protein universe beyond natural evolutionary constraints [1] [9].

Core Technical Principles of RFdiffusion Training

Foundation in RoseTTAFold Architecture

RFdiffusion is constructed using the RoseTTAFold frame representation, which comprises a Cα coordinate and N-Cα-C rigid orientation for each residue [1]. This representation provides a mathematically robust framework for applying noise and learning denoising operations. The model operates through a denoising diffusion probabilistic model (DDPM) framework, where training involves corrupting protein structures from the Protein Data Bank with increasing levels of noise and training the network to reverse this process [1]. During this training, RFdiffusion learns to generate realistic protein backbones by minimizing a mean-squared error (m.s.e.) loss between frame predictions and the true protein structure without alignment, which promotes continuity of the global coordinate frame between timesteps [1].

Training Infrastructure and Noise Scheduling

The training process utilizes a carefully designed noising schedule that corrupts structures over up to 200 steps [1]. For translations, Cα coordinates are perturbed with 3D Gaussian noise, while residue orientations are corrupted using Brownian motion on the manifold of rotation matrices [1]. This mathematical formulation ensures proper diffusion of both positional and orientational components of the protein structure representation. The model is trained to predict the denoised structure (pX0) at each timestep, with the loss function driving denoising trajectories to match the data distribution at each step, ultimately converging on designable protein backbones [1].

Table 1: Key Components of RFdiffusion Training Infrastructure

| Component | Implementation in RFdiffusion | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Base Architecture | Fine-tuned RoseTTAFold structure prediction network | Leverages pre-existing understanding of protein structure |

| Representation | Cα coordinates + N-Cα-C rigid orientations | Mathematically robust framework for noise operations |

| Noise Type (Position) | 3D Gaussian noise on Cα coordinates | Corrupts positional information |

| Noise Type (Orientation) | Brownian motion on SO(3) manifold | Corrupts orientational information |

| Training Loss | Mean-squared error (m.s.e.) without alignment | Maintains global coordinate frame continuity |

| Noising Steps | Up to 200 steps | Progressive corruption of structure |

Self-Conditioning: Enhancing Generative Coherence

Implementation of Self-Conditioning

Self-conditioning represents a significant innovation in the training of RFdiffusion, drawing inspiration from the "recycling" mechanism in AlphaFold2 [1]. In this approach, the model conditions its predictions on outputs from previous timesteps during the denoising trajectory, rather than treating each prediction as independent. This creates a more coherent generative process where structural decisions are informed by prior steps, leading to improved overall quality and designability [1]. The self-conditioning mechanism is implemented by providing the model with its previous predictions as additional inputs during training, establishing a memory mechanism across denoising steps.

Performance Impact of Self-Conditioning

The adoption of self-conditioning has demonstrated substantial improvements in RFdiffusion's performance across multiple design challenges. When evaluated on in silico benchmarks encompassing both conditional and unconditional protein design tasks, the self-conditioning strategy consistently outperformed the canonical approach of making independent predictions at each timestep [1]. This performance improvement is attributed to increased coherence of predictions within self-conditioned trajectories, where structural elements develop more consistently throughout the denoising process [1]. The enhanced coherence translates to higher success rates as measured by computational validation metrics, including AlphaFold2 self-consistency with design models.

Diagram 1: Self-conditioning mechanism in RFdiffusion (Title: Self-Conditioning in RFdiffusion)

Fine-Tuning Strategies for Specialized Applications

Foundational Fine-Tuning from RoseTTAFold Weights

The initial development of RFdiffusion demonstrated that fine-tuning from pre-trained RoseTTAFold weights was dramatically more successful than training from untrained weights for an equivalent duration [1]. This approach leverages the substantial knowledge of protein structure relationships already embedded in RF, repurposing this understanding for generative rather than predictive tasks. The performance advantage of fine-tuning from pre-trained weights was evident across multiple design challenges, establishing this as a foundational principle for developing specialized protein design networks [1].

Task-Specific Fine-Tuning for Antibody Design

A particularly advanced application of fine-tuning is demonstrated in the development of RFdiffusion for de novo antibody design [5] [10]. This specialized variant involves fine-tuning predominantly on antibody complex structures, with modifications to the conditioning approach to maintain antibody framework integrity while designing novel complementarity-determining regions (CDRs). During training, the antibody structure is corrupted while the framework sequence and structure are provided as conditioning input in a global-frame-invariant manner using the template track of RFdiffusion [5]. This approach enables the model to sample alternative rigid-body placements of the antibody relative to the target epitope while preserving the essential immunoglobulin fold.

Epitope-Targeted Fine-Tuning with Hotspot Conditioning

The antibody-design variant of RFdiffusion incorporates an adapted "hotspot" feature that specifies target residues with which CDR loops should interact [5] [10]. This enables precise targeting of specific epitopes while generating diverse CDR-mediated interactions. The fine-tuning process maintains the underlying thermodynamics of interface formation but specializes the network for the distinct structural constraints of antibody-antigen recognition. This approach has enabled the first fully de novo computational design of antibodies targeting user-specified epitopes with atomic-level precision [5].

Table 2: Comparison of Fine-Tuning Strategies for RFdiffusion

| Fine-Tuning Type | Training Data | Conditioning Information | Key Applications | Performance Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Foundation Model | General PDB structures | Secondary structure, functional motifs | Unconditional monomer generation, symmetric oligomers | Far superior to training from scratch [1] |

| Antibody Design | Antibody complex structures | Framework structure, epitope hotspots | VHHs, scFvs, full antibodies targeting specific epitopes | Atomic-level accuracy in CDR loops [5] |

| Binder Design | Protein-protein interfaces | Target structure, interface residues | Protein binders to therapeutic targets | High success rate in experimental validation [1] |

Experimental Protocols for Training RFdiffusion Variants

Protocol: Implementing Self-Conditioning in RFdiffusion Training

Objective: Integrate self-conditioning into RFdiffusion training to improve generative coherence and design success rates.

Materials:

- Pre-trained RoseTTAFold network weights

- Curated Protein Data Bank structures for training

- High-performance computing infrastructure with multiple GPUs

Procedure:

- Initialize Network: Load pre-trained RoseTTAFold weights as starting point for RFdiffusion

- Modify Architecture: Adapt network to incorporate connections for self-conditioning inputs

- Training Loop:

- Sample protein structure (X0) from PDB and random timestep (t)

- Apply t noising steps to generate corrupted structure (Xt)

- For self-conditioning: store previous prediction (pX0{t+1}) from earlier training step

- Provide Xt and optional conditioning information (including previous prediction for self-conditioning) to network

- Compute MSE loss between network prediction (pX0t) and true structure (X0)

- Update network parameters via backpropagation

- Validation: Periodically evaluate on held-out validation set using in silico metrics (AF2 self-consistency, pLDDT, pAE)

Troubleshooting:

- If training instability occurs, adjust learning rate or gradient clipping

- If overfitting observed, increase diversity of training set or implement additional regularization

Protocol: Fine-Tuning RFdiffusion for Antibody Design

Objective: Create specialized RFdiffusion variant for de novo antibody design targeting specific epitopes.

Materials:

- Pre-trained RFdiffusion weights

- Curated antibody-antigen complex structures from PDB

- Target framework sequences for therapeutic antibodies

Procedure:

- Data Curation:

- Collect high-resolution antibody-antigen complex structures

- Annotate framework regions and CDR loops

- Identify epitope residues for hotspot conditioning

- Training Setup:

- Initialize with pre-trained RFdiffusion weights

- Configure template track to provide framework structure as pairwise distances and dihedral angles

- Implement hotspot conditioning for epitope specification

- Specialized Training:

- At each step: sample antibody complex, corrupt antibody structure while preserving target

- Provide framework structure via template track (global-frame-invariant)

- Specify epitope residues via hotspot conditioning

- Train network to recover original antibody structure

- Validation: Use fine-tuned RF2 for antibody structure prediction to assess design quality

Quality Control:

- Verify framework preservation in generated structures

- Assess epitope targeting accuracy through in silico docking

- Experimental validation via yeast display and cryo-EM structure determination

Diagram 2: Fine-tuning workflow for antibody design (Title: Fine-tuning for Antibody Design)

Performance Validation and Metrics

Quantitative Assessment of Training Innovations

The impact of self-conditioning and fine-tuning strategies has been quantitatively evaluated through rigorous in silico benchmarking and experimental validation. For self-conditioning, performance improvements were measured across multiple design challenges, with enhanced performance particularly evident in complex conditional design tasks [1]. Success is typically defined using a stringent computational validation pipeline where designs are considered successful only if the AlphaFold2-predicted structure from the designed sequence shows high confidence (mean pAE < 5), global backbone RMSD < 2 Ã… to the design model, and <1 Ã… RMSD on any scaffolded functional sites [1].

For the antibody-design variant, validation includes both computational and experimental methods. The fine-tuned RFdiffusion successfully generated antibody structures that closely matched input framework structures while targeting specified epitopes with novel CDR loops [5]. Experimental characterization through cryo-EM confirmed atomic-level accuracy in designed CDR conformations, with high-resolution structures nearly identical to design models [5]. Although initial computational designs typically exhibited modest affinity (tens to hundreds of nanomolar Kd), affinity maturation enabled production of single-digit nanomolar binders that maintained intended epitope selectivity [5].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Reagent/Tool | Function/Purpose | Implementation in RFdiffusion |

|---|---|---|

| RoseTTAFold Pre-trained Weights | Foundation for fine-tuning RFdiffusion | Provides initial parameters; knowledge transfer from structure prediction [1] |

| Protein Data Bank (PDB) Structures | Training data for foundational and specialized fine-tuning | Source of native protein structures for training [1] [11] |

| Antibody Complex Structures | Specialized training data for antibody design | Enables fine-tuning for CDR loop and epitope targeting [5] |

| Template Track (RFdiffusion) | Provides structural constraints during generation | Encodes framework structure as pairwise distances/angles [5] |

| Hotspot Conditioning | Guides generation toward specific interactions | Specifies epitope residues for antibody-target interactions [5] |

| ProteinMPNN | Sequence design for generated backbones | Designs sequences encoding the diffused structures [1] |

| Fine-tuned RoseTTAFold2 | Antibody structure prediction for validation | Filters designs by predicting antibody-antigen complexes [5] |

For decades, the field of protein modeling and design has been constrained by fundamental limitations that restricted our ability to explore the vast functional protein universe. Conventional protein engineering methods, such as directed evolution, remained tethered to existing biological templates, performing local searches within the immense landscape of possible protein sequences and structures [9]. This approach confined discovery to incremental improvements and failed to access genuinely novel functional regions beyond natural evolutionary pathways. Physics-based computational design methods, exemplified by tools like Rosetta, demonstrated early success by operating on Anfinsen's hypothesis that proteins fold into their lowest-energy state [9]. These methods employed fragment assembly and force-field energy minimization to design novel proteins like Top7, a 93-residue protein with a fold not observed in nature [9]. However, these approaches faced two critical constraints: their underlying force fields remained approximate, often resulting in designs that misfolded or failed to function in vitro, and the computational expense was prohibitive for exhaustive sampling of sequence-structure space [9].

The core challenge stems from the astronomical scale of the protein functional universe. For a mere 100-residue protein, there are approximately 10^130 possible amino acid arrangements—exceeding the number of atoms in the observable universe [9]. Within this space, naturally occurring proteins represent an infinitesimally small subset, biased by evolutionary history and assayability [9]. This article examines how the integration of artificial intelligence, specifically RFdiffusion and related technologies, has overcome these historical barriers, enabling the precise de novo design of functional proteins with transformative applications across biotechnology and medicine.

The AI-Driven Paradigm Shift: From Prediction to Generation

The breakthrough began with advancements in protein structure prediction. Deep learning networks like AlphaFold2 and RoseTTAFold solved the long-standing problem of predicting a protein's three-dimensional structure from its amino acid sequence with near-experimental accuracy [12]. These models demonstrated a deep understanding of protein structure, but were inherently analytical rather than generative.

The critical transition from predictive analysis to generative design came with the development of RFdiffusion by the Baker Lab [1] [2]. This approach adapted denoising diffusion probabilistic models (DDPMs)—previously successful in image generation—to protein design. RFdiffusion works by fine-tuning a RoseTTAFold structure prediction network on protein structure denoising tasks [1]. The model learns to iteratively "denoise" a random cloud of atom coordinates into a coherent protein backbone through many steps of refinement [1]. Starting from pure noise, RFdiffusion generates elaborate protein structures with little overall similarity to training data, indicating substantial generalization beyond known Protein Data Bank structures [1]. Following backbone generation, the ProteinMPNN network designs sequences encoding these structures [1].

Table 1: Evolution of RFdiffusion Capabilities

| Model Version | Key Innovation | Design Scope | Experimental Validation |

|---|---|---|---|

| RFdiffusion (2023) | Protein backbone generation via diffusion | Protein monomers, binders, symmetric assemblies | Hundreds of tested designs: binders, assemblies, enzymes [1] |

| RFdiffusion All-Atom | Inclusion of small molecule context | Protein-ligand complexes | Design of proteins binding specific ligands [12] |

| Fine-tuned RFdiffusion (2025) | Specialized for antibody loop design | Antibody variable chains (VHHs, scFvs) | Designed binders to influenza HA, C. difficile TcdB [5] [13] |

| RFdiffusion2 (2025) | Enzyme design from chemical transformations | Enzymes with custom active sites | Active enzymes for 5 distinct reactions [14] |

| RFdiffusion3 (2025) | All-atom co-diffusion of biomolecular complexes | Protein complexes with ligands, DNA, RNA | DNA-binding proteins, cysteine hydrolases [12] |

This foundational technology established a new paradigm for protein design, overcoming previous limitations through several key innovations:

- Global exploration: Unlike previous methods confined to local optimization, RFdiffusion can generate entirely novel folds and topologies not observed in nature [1]

- Conditional generation: The model accepts conditioning information including partial sequences, fold specifications, or fixed functional motifs to guide design toward specific objectives [1]

- Computational efficiency: The approach significantly reduces experimental screening burden, with successful designs often identified with as few as one test per design challenge [2]

Breakthrough Application: De Novo Design of Antibodies

A landmark demonstration of RFdiffusion's capabilities came with the de novo design of antibodies targeting specific epitopes—a problem previously considered intractable for computational methods [5]. Despite antibodies being the dominant class of protein therapeutics, with over 160 licensed globally and a market value expected to reach $445 billion, no method previously existed to design epitope-specific antibodies entirely in silico [5].

Methodology: Fine-Tuning RFdiffusion for Antibody Design

The research team fine-tuned RFdiffusion specifically on antibody complex structures to enable design of novel complementarity-determining regions (CDRs) while maintaining the framework region of therapeutic antibodies [5]. The key methodological innovations included:

- Framework conditioning: The antibody framework structure and sequence were provided as conditioning input using the template track of RFdiffusion, represented as a 2D matrix of pairwise distances and dihedral angles [5]

- Epitope specification: A one-hot encoded "hotspot" feature directed antibody CDRs toward user-specified epitopes with atomic-level precision [5]

- Rigid-body sampling: The model designed both CDR loop conformations and the overall orientation of the antibody relative to the target [5]

Following RFdiffusion generation, ProteinMPNN designed sequences for the CDR loops, and a fine-tuned RoseTTAFold2 network filtered designs by re-predicting antibody-antigen complex structures [5]. This filtering step enriched for experimentally successful binders by assessing structural self-consistency—a metric previously unavailable for antibodies due to AlphaFold2's poor performance on antibody-antigen complexes [5].

Diagram 1: RFdiffusion antibody design workflow. The process begins with target epitope specification and proceeds through conditional generation, sequence design, computational filtering, and experimental validation with affinity maturation.

Experimental Protocol and Validation

The experimental validation followed a rigorous protocol across multiple disease-relevant targets, including C. difficile toxin B (TcdB), influenza haemagglutinin, respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), SARS-CoV-2 receptor-binding domain, and IL-7Rα [5]. The specific methodology included:

Design Generation: RFdiffusion generated antibody variable heavy chains (VHHs) and single-chain variable fragments (scFvs) using a humanized VHH framework (h-NbBcII10FGLA) as the structural basis [5]

High-Throughput Screening: Computationally filtered designs were screened using yeast surface display (assessing ~9,000 designs per target for RSV sites I/III, RBD, and influenza haemagglutinin) [5]

Binding Affinity Assessment: Lower-throughput screening employed E. coli expression and single-concentration surface plasmon resonance (SPR) for 95 designs per target (TcdB, IL-7Rα, and influenza haemagglutinin) [5]

Structural Validation: Cryo-electron microscopy determined binding poses for designed VHHs targeting influenza haemagglutinin and TcdB [5]

Affinity Maturation: The OrthoRep system for in vivo continuous evolution further improved binding affinities of initial designs [5]

Table 2: Experimental Results of De Novo Designed Antibodies

| Target | Design Format | Initial Affinity | After Maturation | Structural Validation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Influenza Haemagglutinin | VHH | Tens to hundreds of nM Kd | Single-digit nM Kd | Cryo-EM: nearly identical to design [5] |

| C. difficile TcdB | VHH, scFv | Tens to hundreds of nM Kd | Single-digit nM Kd | Cryo-EM: atomic accuracy of CDRs [5] |

| RSV Sites I/III | VHH | Tens to hundreds of nM Kd | Single-digit nM Kd | High-resolution structure confirmation [5] |

| SARS-CoV-2 RBD | VHH | Tens to hundreds of nM Kd | Single-digit nM Kd | Epitope selectivity maintained [5] |

| PHOX2B peptide–MHC | scFv | Tens to hundreds of nM Kd | Single-digit nM Kd | Combination of heavy/light chains [5] |

The experimental results demonstrated that initial computational designs exhibited modest affinity (tens to hundreds of nanomolar Kd), but affinity maturation enabled production of single-digit nanomolar binders that maintained the intended epitope selectivity [5]. Critically, high-resolution structures confirmed atomic accuracy of the designed complementarity-determining regions, with cryo-EM data for one design verifying the atomically precise conformation of all six CDR loops in a single-chain variable fragment [5].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Workflows

Implementing RFdiffusion-based protein design requires specific computational and experimental resources. The following table details key research reagent solutions essential for successful design campaigns.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for RFdiffusion Design

| Reagent/Tool | Type | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| RFdiffusion (fine-tuned) | Computational Model | Generates antibody structures with novel CDRs | Designing VHHs and scFvs to target epitopes [5] [13] |

| ProteinMPNN | Computational Tool | Designs sequences for generated structures | Sequence design for RFdiffusion-generated backbones [1] |

| RoseTTAFold2 (fine-tuned) | Computational Model | Filters designs by structure prediction | Assessing design self-consistency and binding confidence [5] |

| Yeast Surface Display | Experimental Platform | High-throughput screening of design libraries | Screening ~9,000 designs per target [5] |

| OrthoRep | Experimental System | In vivo continuous evolution for affinity maturation | Improving initial designs to single-digit nM binders [5] |

| Cryo-EM | Structural Biology | High-resolution structure determination | Validating binding poses and CDR conformations [5] |

| ZH8651 | ZH8651, CAS:73918-56-6, MF:C8H10BrN, MW:200.08 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| 2,3-Dihydroxyisovaleric acid | 2,3-Dihydroxy-3-methylbutanoic Acid|Research Chemical | 2,3-Dihydroxy-3-methylbutanoic acid is a key intermediate in branched-chain amino acid biosynthesis. This product is for research use only (RUO). Not for human or veterinary use. | Bench Chemicals |

Advanced Architectures: From RFdiffusion to RFdiffusion3

The RFdiffusion ecosystem has rapidly evolved to address increasingly complex design challenges. RFdiffusion2 introduced specialized capabilities for enzyme design, generating protein backbones with custom active sites from simple descriptions of chemical transformations [14]. This model demonstrated remarkable experimental success, producing active enzymes for five distinct chemical reactions with fewer than 100 designs tested per case—a significant departure from traditional workflows requiring thousands of molecules [14].

The most advanced iteration, RFdiffusion3, represents a quantum leap through its unified all-atom framework [12]. This model operates directly at the atomic level, simultaneously generating protein backbones, sidechains, and complex interactions with ligands, DNA, and other non-protein molecules [12]. Key innovations include:

- All-atom co-diffusion: Concurrently generates proteins and their binding partners from random noise, enabling dynamic mutual adaptation [12]

- Atomic-level conditioning: Imposes precise constraints including hydrogen bonds, solvent accessibility, and symmetry operations [12]

- Computational efficiency: Lightweight transformer-U-Net architecture with sparse attention enables 10-fold speed increase [12]

Experimental validation of RFdiffusion3 included designing a DNA-binding protein for a randomly generated DNA sequence, with one of five tested designs binding with low-micromolar affinity, and engineering a cysteine hydrolase with the best performer achieving kcat/Km of 3557 Mâ»Â¹sâ»Â¹ [12].

Diagram 2: Evolution of RFdiffusion capabilities from protein backbones to all-atom biomolecular design, showing expanding application scope with each iteration.

The development of RFdiffusion and its subsequent specialized versions represents a paradigm shift in protein modeling, effectively overcoming the historical limitations that constrained previous approaches. By transitioning from residue-level approximation to atomic-level precision, these models have closed the resolution gap between computational design and biological function [12]. The experimental success in designing antibodies, enzymes, and DNA-binding proteins purely through computation demonstrates that the field has entered an era where the primary limitation is no longer the design tools themselves, but the creativity and biological insight of researchers applying them [12] [9].

Future advancements will likely focus on integrating these design capabilities with high-throughput experimental validation platforms, creating a continuous feedback loop that further refines computational models. Additional challenges remain, including incorporating post-translational modifications and glycosylation, and improving the prediction and design of conformational dynamics [12]. Nevertheless, RFdiffusion has unequivocally transformed protein engineering from a template-dependent process to a rational design discipline, fundamentally expanding our ability to explore the vast untapped potential of the protein functional universe for therapeutic, catalytic, and synthetic biology applications.

RFdiffusion in Practice: Methodology and Diverse Applications

The de novo design of proteins represents a paradigm shift in biotechnology, moving from predicting natural proteins to creating entirely new proteins with customized structures and functions. RFdiffusion, a deep-learning framework based on a diffusion model, has emerged as a powerful tool for this purpose, enabling researchers to generate diverse protein structures that can be experimentally validated for specific applications, including therapeutic development, enzyme design, and antibody engineering [1] [15]. This application note provides a detailed overview of the RFdiffusion workflow, from its fundamental noise-to-structure generation process to the experimental protocols required for functional validation. The methodology is framed within the broader context of expanding the explorable protein functional universe, moving beyond the constraints of natural evolution to access novel folds and functions [9].

The core innovation of RFdiffusion lies in its adaptation of the RoseTTAFold structure prediction network, which is fine-tuned on protein structure denoising tasks. This transforms it into a generative model capable of creating protein backbones through an iterative denoising process [1]. By starting from random noise and progressively applying denoising steps, RFdiffusion can generate novel, designable protein backbones that fulfill specific design challenges, such as binding to a target protein, forming symmetric assemblies, or scaffolding functional active sites [1].

Core Mechanism: From Noise to Structure

The Denoising Diffusion Process

The RFdiffusion workflow is grounded in Denoising Diffusion Probabilistic Models (DDPMs). The process involves two main phases: a forward noising process and a reverse denoising process. During training, protein structures from the Protein Data Bank (PDB) are progressively corrupted with Gaussian noise over a series of timesteps (T), disrupting their coordinates and orientations [1] [5]. The network learns to predict the original, uncorrupted structure from any given noised state.

At inference time, the process is reversed to generate new proteins:

- Initialization: The process begins with a set of random residue frames, where each frame consists of a Cα coordinate and an N-Cα-C orientation [1].

- Iterative Denoising: RFdiffusion takes these random frames and makes a prediction of the denoised structure. Each residue frame is then updated by moving in the direction of this prediction, with a controlled amount of noise added back to generate the input for the next step [1].

- Structure Formation: Initially, the predictions from the random frames do not resemble proteins. However, over many denoising steps (up to 200), the possible structures from which the input could have arisen become more defined, and the output converges on a coherent, protein-like backbone structure [1].

A key technical aspect is the use of a mean-squared error (m.s.e.) loss during training, which promotes continuity in the global coordinate frame between timesteps, unlike the Frame Aligned Point Error (FAPE) loss used in standard RoseTTAFold training [1]. Furthermore, the incorporation of self-conditioning—allowing the model to condition its predictions on its own outputs from previous timesteps—significantly improves the coherence and quality of the generated structures compared to canonical diffusion approaches [1].

Conditioning for Functional Design

The true power of RFdiffusion for applied research lies in its ability to accept conditioning information, which guides the generation process to meet specific design objectives. This is analogous to text-guided image generation models [1]. The network can be conditioned on various inputs provided at the individual residue, inter-residue, or 3D coordinate levels, enabling precise control over the final output.

Table: Common Conditioning Strategies in RFdiffusion

| Conditioning Type | Input Provided | Design Application |

|---|---|---|

| Fixed Functional Motifs | 3D coordinates of a specific motif (e.g., an enzyme active site) [1] | Scaffolding active sites into new protein folds [14] |

| Partial Structure | A portion of the protein structure is held fixed [1] [5] | Designing binders or antibodies by keeping the framework fixed and designing flexible loops [5] |

| Target Epitope | Structure of a target protein with specified "hotspot" residues [5] | De novo design of antibodies or protein binders to a specific epitope [5] |

| Symmetry Operators | Mathematical definition of rotational or translational symmetry [1] | Design of symmetric oligomers and higher-order protein assemblies [1] |

| Fold Information | Secondary structure and block-adjacency information [1] | Topology-constrained protein monomer design |

The following diagram illustrates the complete workflow, integrating the core denoising process with key conditioning strategies and downstream experimental steps.

Detailed Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: De Novo Protein Monomer Design

This protocol details the generation of a novel protein fold without a specific functional site, testing the model's ability to explore uncharted regions of the protein structural universe [1] [9].

Procedure:

- Unconditional Generation: Run RFdiffusion without any conditioning input, starting from completely random residue frames [1].

- Structure Generation: Allow the model to perform iterative denoising for the full number of timesteps (e.g., 200) to produce a final backbone structure.

- Sequence Design: Input the generated backbone into ProteinMPNN to design a protein sequence that stabilizes the fold. Typically, 8 sequences are sampled per design for diversity [1].

- In Silico Validation:

- Use AlphaFold2 or ESMFold to predict the structure of the designed sequence.

- Define a successful design by three criteria [1]:

- High confidence prediction (mean pAE < 5).

- Global backbone RMSD < 2 Ã… compared to the RFdiffusion model.

- For any scaffolded functional site, local backbone RMSD < 1 Ã….

Expected Outcomes: Successful designs will be diverse, spanning alpha, beta, and mixed alpha-beta topologies, and will often show little overall structural similarity to proteins in the PDB, demonstrating generalization beyond the training data [1]. Experimental characterization of such designs via circular dichroism should reveal spectra consistent with the designed secondary structure and high thermal stability [1].

Protocol 2: De Novo Antibody Design

This protocol leverages a specialized version of RFdiffusion fine-tuned on antibody complex structures to design antibodies targeting specific epitopes [5].

Procedure:

- Framework Specification: Select a well-characterized antibody framework (e.g., a humanized VHH framework for single-domain antibodies). Provide its sequence and structure as a fixed conditioning input to the model via the template track, which encodes pairwise distances and orientations [5].

- Epitope Conditioning: Provide the structure of the target antigen, with specific "hotspot" residues on the epitope marked to direct the designed CDR loops [5].

- Structure Generation: Run the fine-tuned RFdiffusion. The model will sample different rigid-body docking positions and generate novel conformations for the Complementarity-Determining Regions (CDRs) while keeping the framework stable.

- Sequence Design: Use ProteinMPNN to design the sequences for the generated CDR loops.

- In Silico Filtering:

- Use a specialized, fine-tuned version of RoseTTAFold2 that is provided with the target structure and epitope information to re-predict the structure of the designed antibody-antigen complex [5].

- Filter designs where the predicted structure is highly confident and nearly identical to the designed model.

- Perform in silico cross-reactivity analysis to check for off-target binding [5].

Expected Outcomes: Initial computational designs may exhibit modest binding affinity (nanomolar to hundreds of nanomolar Kd). Affinity maturation (e.g., using OrthoRep) can subsequently produce single-digit nanomolar binders while maintaining epitope specificity [5]. Cryo-electron microscopy structures of successful designs confirm atomic-level accuracy in CDR loop conformations and binding poses [5].

Protocol 3: Enzyme Active Site Scaffolding

This protocol uses RFdiffusion2, an advanced version of the model, to scaffold a functional enzyme active site (a "theozyme") into a stable, novel protein backbone [14].

Procedure:

- Theozyme Input: Define the desired catalytic site by specifying the key residues and their geometric arrangements necessary for the chemical reaction. RFdiffusion2 can work with minimally defined catalytic sites without requiring pre-set rotamers or indexed atomic positions, offering greater flexibility [14].

- Conditioned Generation: Condition RFdiffusion2 on this theozymal motif. The model will generate a complete protein backbone that encapsulates the active site.

- Sequence Design: Use ProteinMPNN to design the full protein sequence, including both the active site and the stabilizing scaffold.

- In Silico Validation: Validate designs using the Atomic Motif Enzyme (AME) benchmark. Confirm that the designed structure is designable and that the active site geometry is preserved [14].

Expected Outcomes: RFdiffusion2 has demonstrated a high success rate in lab tests, producing active enzymes for distinct reactions (e.g., retroaldolase, hydrolases) while testing fewer than 100 designs per case—a significant reduction compared to traditional methods that require screening thousands of variants [14]. Designed metallohydrolases have shown orders-of-magnitude higher activity than previous engineered versions [14].

Table: Quantitative Performance of RFdiffusion Across Design Challenges

| Design Challenge | In Silico Success Metric | Experimental Success / Activity | Key Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protein Monomers | AF2 confidence (pAE <5) & global RMSD <2Ã… [1] | High stability; CD spectra match design [1] | [1] |

| Protein Binders | Similar to monomer, plus interface RMSD <1Ã… [1] | Cryo-EM confirms near-identical complex [1] | [1] |

| De Novo Antibodies (VHHs) | Fine-tuned RF2 confidence & low interface RMSD [5] | Initial Kd in nM range; affinity maturation to sub-10 nM [5] | [5] |

| Enzymes (RFdiffusion2) | Solved 41/41 cases in AME benchmark [14] | Active enzymes with <<100 designs tested per reaction [14] | [14] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following table catalogues key computational and experimental reagents essential for implementing the RFdiffusion workflow.

Table: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Reagent / Tool Name | Type | Function in Workflow | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| RFdiffusion | Deep Learning Model | Core generative engine for protein backbone structures. | Fine-tuned from RoseTTAFold; uses diffusion model; accepts diverse conditioning inputs [1]. |

| RFdiffusion2 | Deep Learning Model | Advanced version for enzyme design and other applications. | Employs flow matching; handles unindexed atomic motifs for flexible active site scaffolding [14]. |

| ProteinMPNN | Deep Learning Model | Designs amino acid sequences for a given protein backbone. | Fast, robust sequence design; high experimental success rate for stabilizing designed folds [1]. |

| AlphaFold2 (AF2) | Validation Tool | In silico validation of designed structures via self-consistency. | Predicts structure from sequence; used to check if designed sequence folds into intended structure [1] [16]. |

| Fine-tuned RoseTTAFold2 | Validation Tool | Specialized structure prediction for antibody-antigen complexes. | Critical for filtering antibody designs; requires holo target and epitope info for accuracy [5]. |

| Rosetta | Software Suite | Physics-based energy calculations (ddG) for interface quality. | Evaluates the energetic favorability of designed protein-protein interfaces [5]. |

| Yeast Surface Display | Experimental Platform | High-throughput screening of designed binders (e.g., antibodies). | Allows screening of thousands of designs to identify binders for a given target [5]. |

| Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) | Analytical Instrument | Quantifies binding affinity (Kd) and kinetics of designed proteins. | Provides quantitative data on the strength and character of target binding [5]. |

| Cryo-Electron Microscopy | Structural Biology Tool | Experimental high-resolution structure determination of complexes. | Gold-standard verification that the designed protein-target complex matches the computational model [1] [5]. |

| 2-Pyridinecarbothioamide | Pyridine-2-carbothioamide|Research Chemical|CAS 5346-38-3 | Bench Chemicals | |

| 11-Deoxy-16,16-dimethyl-PGE2 | 11-Deoxy-16,16-dimethyl-PGE2, MF:C22H36O4, MW:364.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

The RFdiffusion workflow represents a mature and powerful framework for the de novo design of functional proteins. By leveraging a noise-to-structure generative process guided by precise conditioning, it enables the creation of proteins that meet exact research and therapeutic specifications. The detailed protocols for monomer, antibody, and enzyme design provide a roadmap for researchers to apply this technology. As these tools continue to evolve, they are poised to dramatically accelerate the exploration of the protein functional universe, paving the way for bespoke biomolecules with tailored functionalities for medicine and biotechnology [15] [9].

RFdiffusion represents a transformative advancement in de novo protein design, enabling researchers to generate novel protein structures through conditional guidance rather than unconditional generation. This guided diffusion approach allows precise control over generated structures by incorporating molecular specifications as conditioning information during the denoising process. By fine-tuning the RoseTTAFold structure prediction network on protein structure denoising tasks, RFdiffusion obtains a generative model of protein backbones that achieves outstanding performance across diverse design challenges when provided with appropriate conditioning inputs [1]. The conditioning mechanism operates by providing auxiliary information to the network during the iterative denoising process, steering the generation toward structures that fulfill specific functional or structural requirements.

The power of RFdiffusion's conditioning strategies lies in their ability to solve a wide range of design challenges, including de novo binder design, symmetric oligomer generation, functional motif scaffolding, and enzyme active site design [1] [2]. This capability has profound implications for biomedical research and therapeutic development, as it enables the computational generation of proteins with atom-level precision for specific applications. By leveraging different conditioning strategies, researchers can now design proteins that target specific epitopes with atomic accuracy, scaffold functional motifs within novel protein structures, and create symmetric assemblies with precisely positioned functional elements [5] [17].

Core Conditioning Mechanisms in RFdiffusion

Architectural Foundation

RFdiffusion builds upon the RoseTTAFold2 (RF2) architecture, which provides a robust foundation for processing three-dimensional structural information. The network employs a three-track architecture that jointly reasons about sequence, distance, and coordinate information, enabling it to handle complex structural relationships essential for conditional protein design [18]. During training, RFdiffusion learns to reverse a corruption process where protein structures are progressively noisy through the addition of Gaussian noise to Cα coordinates and Brownian motion perturbations to residue orientations [1]. This training regimen enables the network to generate novel, designable protein backbones when conditioned on specific molecular specifications.

A critical technical aspect of RFdiffusion is its use of mean-squared error (MSE) loss rather than the frame-aligned point error (FAPE) loss typically used in structure prediction networks like AlphaFold2. The MSE loss promotes continuity of the global coordinate frame between timesteps, which is essential for maintaining consistency throughout the diffusion process [18]. Additionally, the implementation of self-conditioning, where the model conditions on previous predictions between timesteps, significantly improves performance compared to canonical diffusion approaches where predictions at each timestep are independent [1]. This self-conditioning strategy increases coherence within denoising trajectories and contributes to the method's exceptional performance.

Conditioning Input Representation

RFdiffusion accepts various types of conditioning information that are integrated through different network pathways. The primary conditioning mechanism utilizes the template track of RF2 to provide structural information as a two-dimensional matrix of pairwise distances and dihedral angles between residues [5]. This representation encodes three-dimensional structural relationships while remaining invariant to global rotations and translations, which is essential for flexible docking applications. For epitope-specific antibody design, researchers can provide "hotspot" residues on the target protein using a one-hot encoded feature that directs the generated CDR loops to interact with specified regions [5].

Table: Core Conditioning Input Types in RFdiffusion

| Conditioning Type | Representation Format | Network Pathway | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Structural Templates | Pairwise distances and dihedral angles | Template track | Framework preservation, motif scaffolding |

| Sequence Masks | One-hot encoded residue specifications | 1D sequence track | Active site design, sequence constraints |

| Hotspot Residues | One-hot encoded interface residues | 2D/3D tracks | Binder design, epitope targeting |

| Symmetry Operators | Symmetry-specific transformations | 3D coordinate track | Symmetric oligomer generation |

| Fold Information | Secondary structure & block adjacency | 2D track | Topology-constrained design |

The contig string system provides a flexible language for specifying complex design requirements, enabling researchers to define which portions of a structure should be fixed versus designed, specify connectivity between segments, and control structural sampling [19]. For example, a contig string of [5-15/A10-25/30-40] would direct RFdiffusion to build 5-15 residues N-terminally of motif A10-25 from an input PDB, followed by 30-40 residues C-terminally, with the length ranges randomly sampled during each inference cycle to explore diverse solutions [19].

Key Conditioning Strategies and Applications

Epitope-Specific Antibody Design

The conditioning strategy for de novo antibody design represents one of RFdiffusion's most sophisticated applications. By fine-tuning the network predominantly on antibody complex structures and providing the antibody framework as conditioning input, researchers can generate novel complementarity-determining regions (CDRs) that target user-specified epitopes with atomic-level precision [5]. The framework structure is provided in a global-frame-invariant manner using the template track, allowing RFdiffusion to design both the CDR loop conformations and the overall rigid-body placement of the antibody relative to the target [5].

This approach has demonstrated remarkable success in designing single-domain antibodies (VHHs) targeting disease-relevant proteins including influenza haemagglutinin, Clostridium difficile toxin B (TcdB), respiratory syncytial virus sites, SARS-CoV-2 receptor-binding domain, and IL-7Rα [5]. Experimental validation through cryo-electron microscopy confirmed that designed VHHs bind in the intended pose with atomic accuracy in their CDR regions. Although initial computational designs typically exhibit modest affinity (tens to hundreds of nanomolar Kd), subsequent affinity maturation can produce single-digit nanomolar binders that maintain the intended epitope specificity [5].

Functional Motif Scaffolding

Motif scaffolding represents a fundamental conditioning strategy where RFdiffusion generates novel protein structures that encapsulate and display functional motifs while preserving their structural integrity and function. This approach conditions the diffusion process on fixed motif coordinates, requiring the network to generate complementary structural elements that stabilize the motif without altering its functional conformation [1] [18]. The contig mapping system enables precise specification of which motif residues should remain fixed and which regions should be designed, with control over the length ranges of connecting segments [19].

In benchmark tests across 25 motif scaffolding challenges derived from recent literature, RFdiffusion successfully solved 23 problems, significantly outperforming previous methods [18]. The method has demonstrated particular utility in enzyme active site scaffolding, where it can generate novel scaffolds around specified catalytic residues, creating functional enzymes with novel topologies not found in nature [1]. This capability was further extended to symmetric functional motif scaffolding, where RFdiffusion designs symmetric oligomers that precisely position functional motifs for enhanced binding or catalysis [18].

Table: Performance Metrics for RFdiffusion Conditioning Strategies

| Application Domain | Conditioning Input | Success Rate | Experimental Validation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Antibody Design | Framework + hotspot residues | 19% experimental binders [18] | Cryo-EM structures at atomic resolution [5] |

| Motif Scaffolding | Fixed motif coordinates | 23/25 benchmark problems [18] | High-resolution design confirmation [1] |

| Symmetric Oligomers | Symmetry operators + motif | 87/608 designs [18] | SEC, nsEM validation [18] |

| Enzyme Design | Active site residues | 15% active designs [17] | Catalytic efficiency up to 2.2×10âµ Mâ»Â¹sâ»Â¹ [17] |

| Protein Binders | Target surface + hotspots | Picomolar affinity achieved [2] | Crystal structures with <1.5Ã… RMSD [17] |

Symmetric Assembly Design

Symmetric oligomer design represents another powerful conditioning strategy where RFdiffusion generates protein assemblies with cyclic, dihedral, or cubic symmetries. This approach conditions the diffusion process on symmetry operators that enforce equivalent relationships between subunits throughout the generation process [18]. The network employs explicit resymmetrization during each denoising step and leverages the equivariant properties of the underlying architecture to maintain symmetry [1].