Protein Engineering for Therapeutic Antibodies: From AI-Driven Design to Clinical Applications

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the current landscape and future directions of protein engineering for therapeutic antibodies, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Protein Engineering for Therapeutic Antibodies: From AI-Driven Design to Clinical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the current landscape and future directions of protein engineering for therapeutic antibodies, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational shift from traditional methods to computational and AI-driven design, detailing core methodologies like rational design, directed evolution, and advanced display technologies. The scope extends to troubleshooting critical developability challenges—such as immunogenicity, stability, and aggregation—and concludes with a comparative analysis of clinical and commercial validation, synthesizing key takeaways to guide future R&D strategies in biomedicine.

The New Frontier: How Computational Tools are Reshaping Antibody Therapeutics

The global biologics market has demonstrated exceptional growth, driven significantly by the dominance of monoclonal antibodies (mAbs). The market data underscores a robust expansion, solidifying the commercial and therapeutic impact of antibody-based therapies.

Table 1: Global Biologics Market Size and Projections

| Metric | 2024/2025 Value | 2030/2034 Value | CAGR (Compound Annual Growth Rate) | Source Segment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall Biologics Market | USD 444.40 billion (2024) [1] | USD 1,144.20 billion (2034) [1] | 9.96% (2025-2034) [1] | - |

| Biologics Manufacturing Market | USD 33.52 billion (2024) [2] | USD 162.51 billion (2034) [2] | 17.1% (2025-2034) [2] | - |

| Monoclonal Antibodies (Product Segment) | USD 274.4 billion (2024) [3] | - | - | - |

| Mammalian Source Systems | 71.34% market share (2024) [3] | - | - | Chinese Hamster Ovary (CHO) cells are the dominant mammalian platform [4] [3]. |

| Microbial Source Systems | 58.78% market share (2024) [1] | - | - | Includes E. coli and yeast [5] [1]. |

The monoclonal antibodies segment is the undisputed leader within the biologics market, accounting for an estimated 56.48% of the market by product in 2024 and generating USD 274.4 billion in revenue [1] [3]. This dominance is attributed to their high specificity, success in clinical applications, and their ability to target diseased cells without harming healthy ones [2] [1]. The oncology therapeutic area commands the largest share at 36.54%, growing at a remarkable CAGR of 13.78%, fueled by the adoption of immunotherapies, antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs), and CAR-T therapies [3].

From a manufacturing perspective, mammalian expression systems, particularly CHO cells, are preferred for producing complex, glycosylated therapeutic antibodies, holding over 71% of the market share by source [2] [3]. This preference stems from their ability to perform human-like post-translational modifications, which are critical for the efficacy and stability of therapeutic proteins [4].

Protein Engineering Strategies for Therapeutic Antibodies

Protein engineering is central to advancing therapeutic antibodies, enabling the enhancement of affinity, stability, and pharmacological properties. These strategies can be broadly classified into directed evolution and rational design.

Directed Evolution and Display Technologies

Directed evolution mimics natural selection in a laboratory setting to isolate antibody variants with desired traits from vast diverse libraries [6].

Phage Display: This pioneering technology, for which the 2018 Nobel Prize in Chemistry was awarded, involves fusing antibody fragments (e.g., scFv, Fab) to a coat protein of a bacteriophage [6]. The process of biopanning allows for the isolation of high-affinity binders through iterative cycles of:

- Incubation: The phage library is exposed to the immobilized target antigen.

- Washing: Non-specific or weak binders are removed.

- Elution: Specifically bound phages are recovered and amplified in E. coli for the next round [6]. Successful drugs like adalimumab (Humira) for rheumatoid arthritis and belimumab (Benlysta) for lupus were discovered and optimized using phage display [6].

Other Display Platforms: Yeast surface display and ribosome/mRNA display are other powerful technologies. Ribosome/mRNA display is a cell-free system that can generate exceptionally large libraries (10^12-10^14 clones) and is not limited by bacterial transformation efficiency, allowing for the isolation of antibodies with picomolar affinities [6].

Rational Design and Engineering Approaches

Rational design employs structural knowledge and computational tools to make precise modifications to antibody sequences [7].

Affinity and Stability Optimization: Site-directed mutagenesis is used to improve antibody characteristics. For instance, computational tools like Spatial Aggregation Propensity (SAP) can identify regions prone to aggregation, guiding mutations that enhance stability [7]. Substituting free cysteine residues with serine prevents unwanted disulfide bond formation and oxidation, a strategy used in approved drugs like pegfilgrastim (Neulasta) [7].

Fc Engineering for Enhanced Pharmacokinetics: The circulating half-life of antibodies is modulated by their interaction with the neonatal Fc receptor (FcRn). Introducing specific point mutations (e.g., M428L/N434S, known as the "LS" variant) in the Fc region increases antibody half-life by enhancing FcRn binding at acidic pH, promoting recycling over lysosomal degradation. This engineering approach is utilized in ravulizumab (Ultomiris), which has an extended dosing interval compared to its predecessor [7].

Reducing Immunogenicity: A key goal in protein engineering is to minimize immune responses. Techniques like humanization—replacing murine sequences with human counterparts in antibodies derived from mice—drastically reduce immunogenicity [6]. Further deimmunization strategies involve identifying and mutating potential T-cell epitopes within the antibody sequence [7].

Formulating Bispecifics and Antibody-Drug Conjugates (ADCs): Engineering has enabled the creation of bispecific antibodies that can engage two different targets simultaneously, and ADCs that deliver potent cytotoxic drugs directly to cancer cells, maximizing efficacy and minimizing systemic toxicity [3].

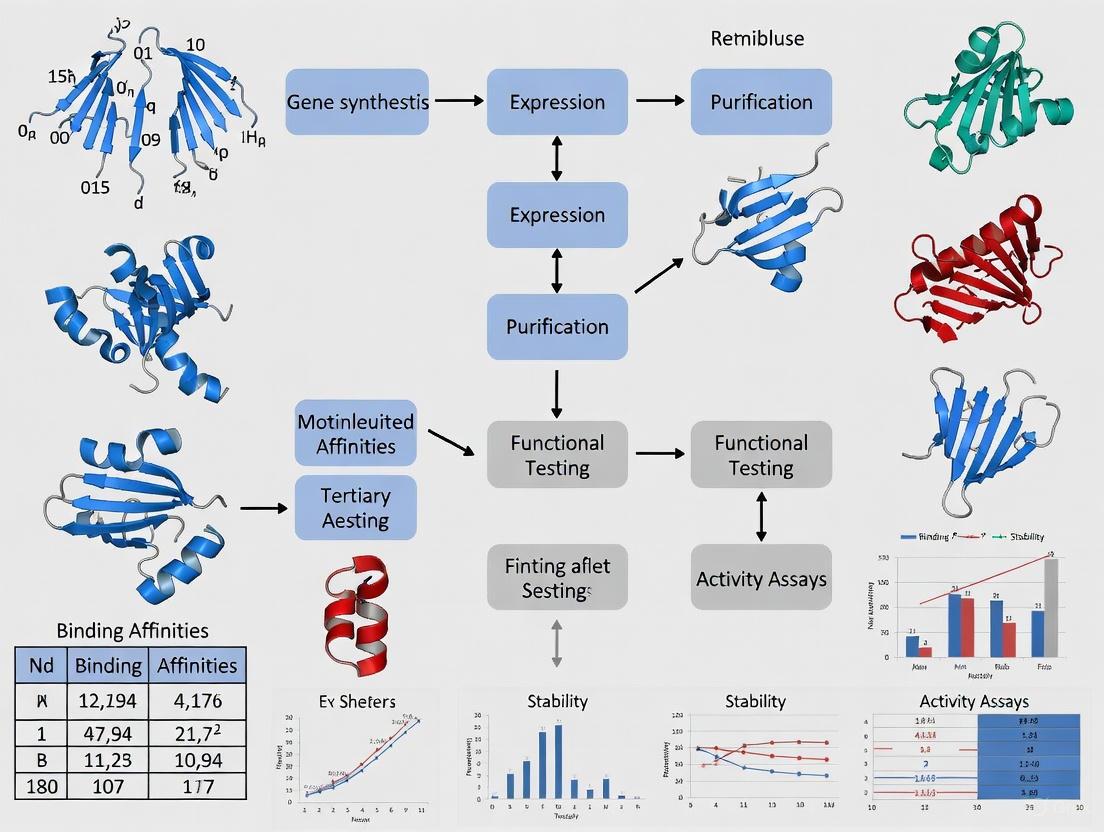

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow and key decision points in the antibody engineering and development process.

Application Notes: Detailed Experimental Protocols

This section provides detailed methodologies for key experiments in antibody development, from discovery to biophysical characterization.

Protocol 1: Phage Display Biopanning for Antibody Selection

Objective: To isolate antigen-specific antibody fragments (scFv or Fab) from a naive or immune phage display library through iterative selection rounds [6].

Materials:

- Phage display library (e.g., human scFv library)

- Target antigen (recombinant protein, purified)

- Immunotubes or ELISA plates for immobilization

- Washing buffers (PBS with 0.1% Tween-20, PBS alone)

- Elution buffer (0.1 M Glycine-HCl, pH 2.2, or Triethylamine)

- Neutralization buffer (1 M Tris-HCl, pH 9.1)

- E. coli strains for infection (e.g., TG1)

- Culture media (2xYT with appropriate antibiotics)

Procedure:

- Antigen Coating: Coat an immunotube or well with 1-10 µg/mL of target antigen in PBS overnight at 4°C. Include a negative control well without antigen.

- Blocking: Block the coated surface with 2-4% Marvel/PBS (or BSA/PBS) for 1-2 hours at room temperature to prevent non-specific binding.

- Phage Incubation: Incubate the phage library (10^12-10^13 phage particles) in blocking buffer for 1-2 hours to allow binding.

- Washing: Remove unbound phages by rigorous washing.

- First Round: 10-20 washes with PBS/0.1% Tween-20, followed by 10-20 washes with PBS.

- Subsequent Rounds: Increase stringency by increasing the number of washes or Tween concentration.

- Elution: Recover specifically bound phages using two methods:

- Acidic Elution: Add 0.5-1 mL of 0.1 M Glycine-HCl (pH 2.2) for 5-15 minutes. Immediately neutralize with 0.5-1 mL of 1 M Tris-HCl (pH 9.1).

- Competitive Elution (Alternative): Incubate with excess soluble antigen for 30-60 minutes.

- Amplification: Infect log-phase E. coli TG1 cells with the eluted phages. Culture the infected cells to amplify the phage pool for the next selection round. Helper phages are added to rescue the phagemid particles.

- Titration: Determine the input and output phage titers after each round to monitor enrichment. A significant increase in output titer on antigen-coated wells compared to control indicates successful selection.

- Repeat: Typically, 3-4 rounds of biopanning are performed to sufficiently enrich for high-affinity binders.

- Screening: After the final round, isolate single clones for screening (e.g., via ELISA) to identify antigen-positive antibody fragments.

Protocol 2: Site-Directed Mutagenesis for Fc Engineering

Objective: To introduce specific point mutations (e.g., M428L/N434S) into the Fc region of an IgG antibody to enhance FcRn binding and extend serum half-life [7].

Materials:

- Plasmid DNA containing the gene for the IgG antibody of interest.

- High-fidelity DNA polymerase (e.g., PfuUltra).

- DpnI restriction enzyme.

- Mutagenic primers designed for the desired mutation.

- Competent E. coli cells.

Procedure:

- Primer Design: Design and synthesize complementary forward and reverse primers (25-45 bases) that contain the desired mutation in the center, flanked by 10-15 correct nucleotides on each side.

- PCR Amplification: Set up a PCR reaction using the plasmid as a template and the mutagenic primers. The high-fidelity polymerase will amplify the entire plasmid, incorporating the mutation.

- Typical Thermocycler Conditions:

- Initial Denaturation: 95°C for 2 minutes.

- 18 Cycles:

- Denature: 95°C for 30 seconds.

- Anneal: 55-65°C for 1 minute.

- Extend: 72°C for 1-2 minutes per kb of plasmid length.

- Final Extension: 72°C for 10 minutes.

- Typical Thermocycler Conditions:

- DpnI Digestion: After PCR, treat the reaction mixture with DpnI for 1 hour at 37°C. DpnI cleaves the methylated parental DNA template, leaving the newly synthesized, mutated DNA strand intact.

- Transformation: Transform the DpnI-treated DNA into competent E. coli cells.

- Screening and Sequencing: Plate the cells and pick colonies. Isolate plasmid DNA and verify the introduction of the correct mutation by DNA sequencing.

- Protein Expression: Transfect the validated plasmid into mammalian expression cells (e.g., HEK293 or CHO) for transient or stable expression of the engineered full-length antibody.

Protocol 3: Tangential Flow Filtration (TFF) for mAb Purification

Objective: To concentrate and buffer-exchange a clarified cell culture harvest containing a monoclonal antibody, as a key step in downstream processing [4].

Materials:

- Clarified cell culture supernatant.

- Tangential Flow Filtration system with a peristaltic pump.

- Pellicon cassette or hollow fiber module (appropriate MWCO, e.g., 30 kDa for mAbs).

- Diafiltration buffer (e.g., PBS for final formulation, or a different buffer for intermediate purification).

- Conductivity and pH meters.

Procedure:

- System Setup and Equilibration: Assemble the TFF system according to the manufacturer's instructions. Flush the system and membrane with water, then equilibrate with diafiltration buffer.

- Concentration:

- Load the clarified harvest into the feed reservoir.

- Recirculate the fluid, applying pressure to force buffer and small molecules (permeate) through the membrane while retaining the antibody (retentate).

- Continue until the desired concentration factor (e.g., 10x) is achieved.

- Diafiltration (Buffer Exchange):

- Once concentrated, begin adding diafiltration buffer to the retentate reservoir at the same rate as the permeate is removed. This process washes out small impurities and exchanges the buffer.

- Typically, 5-10 volume exchanges are performed to ensure >99% buffer exchange.

- Final Recovery:

- After diafiltration, recover the concentrated and buffer-exchanged retentate.

- Flush the system with a small volume of buffer to maximize product recovery.

- Cleaning and Storage: Clean the TFF membrane immediately after use according to the manufacturer's protocol (e.g., with NaOH solution) and store in an appropriate preservative.

The following workflow diagram maps the key stages of the antibody biomanufacturing process.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Reagents and Materials for Antibody Research and Development

| Item | Function/Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| CHO (Chinese Hamster Ovary) Cells | Mammalian host cell line for producing full-length, glycosylated therapeutic antibodies [5] [4]. | Capable of human-like post-translational modifications; requires complex media and controlled bioreactor conditions [3]. |

| Phagemid Vectors | Plasmids used in phage display to display antibody fragments on the surface of filamentous phage (e.g., M13) [6]. | Contains both bacterial and phage origins of replication, antibiotic resistance marker, and a fusion gene for a coat protein (pIII or pVIII) [6]. |

| Protein A/G/L Chromatography Resins | Affinity chromatography matrices for purifying antibodies and Fc-fusion proteins from complex mixtures like cell culture supernatant [4]. | Binds with high specificity to the Fc region of antibodies; a cornerstone of downstream purification processes [4]. |

| Single-Use Bioreactors | Disposable bags used for cell culture in upstream biomanufacturing [4] [3]. | Eliminates cross-contamination risk and reduces cleaning validation; enables flexible and scalable production [4] [3]. |

| TFB (Transformation Buffer) | Chemically competent E. coli cells used for high-efficiency transformation following mutagenesis or library construction [6]. | Essential for cloning steps, library amplification, and plasmid propagation. |

| Ethylenethiourea-d4 | Ethylenethiourea-d4, CAS:352431-28-8, MF:C3H6N2S, MW:106.19 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 2,3-Dichlorobenzoic acid-13C | 2,3-Dichlorobenzoic acid-13C, CAS:1184971-82-1, MF:C7H4Cl2O2, MW:192.00 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The field of therapeutic antibody development has undergone a profound transformation, evolving from biologically-driven methods reliant on the immune systems of animals to sophisticated computational design performed entirely in silico [8]. This paradigm shift is rooted in protein engineering, which applies principles of rational design, directed evolution, and, most recently, artificial intelligence (AI) to create antibodies with enhanced specificity, efficacy, and safety profiles [9]. The journey began with hybridoma technology, which enabled the production of murine monoclonal antibodies, and progressed through chimeric, humanized, and fully human antibodies to mitigate immunogenicity [8]. Today, the integration of AI and machine learning (ML) is reshaping the discovery landscape, dramatically accelerating timelines and enabling the targeting of previously "undruggable" epitopes [10] [11]. This article details the key methodologies driving this evolution, providing application notes and experimental protocols for researchers and drug development professionals.

Evolution of Antibody Discovery Platforms

The following table summarizes the quantitative progression of key technologies that have defined the antibody discovery landscape, highlighting the transition from biological to computational dominance.

Table 1: Key Metrics in the Evolution of Antibody Discovery Platforms

| Discovery Platform | Timeline (First Approved Drug) | Key Advantage | Key Limitation | Impact on Discovery Timelines |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hybridoma Technology [8] | 1980s (Muromonab-CD3, 1986) | High-affinity, native paired antibodies | Murine origin leads to immunogenicity (HAMA response) | 12-18 months |

| Phage Display [8] [12] | 1990s (Adalimumab, 2002) | Bypasses immunization; fully human antibodies | Limited to smaller constructs (e.g., scFv); bacterial folding machinery | 9-12 months |

| Transgenic Mice [8] | 2000s (Panitumumab, 2006) | Fully human antibodies with native pairing | Complex and costly platform development | 10-14 months |

| Single B-Cell Screening [8] | 2010s | Preserves native heavy-light chain pairing; rapid for infectious diseases | Requires specific patient/donor samples | 6-9 months |

| AI/ML & In Silico Design [13] [11] | 2020s (Clinical candidates, e.g., Imneskibart) | De novo design; targets "undruggable" proteins; minimal immunogenicity | Requires high-quality, large-scale data for training | < 6 weeks for initial candidate generation |

The market dynamics reflect this technological evolution. The global antibody discovery market, valued at USD 2.06 billion in 2025, is projected to grow at a CAGR of 9.8% to reach USD 5.25 billion by 2035 [12]. A significant trend is the segment growth by antibody type, where fully human antibodies are poised to dominate due to demand for reduced immunogenicity and enhanced efficacy in personalized medicine [12].

Table 2: Antibody Discovery Market Growth by Type (2025-2035 Projection)

| Antibody Type | Key Driver | Projected Market Dominance |

|---|---|---|

| Murine Antibody | Historical use; regulatory familiarity | Ceding ground |

| Chimeric Antibody | Reduced immunogenicity vs. murine | Stable niche |

| Humanized Antibody | Further reduced immunogenicity | Widely used |

| Human Antibody | Minimal immunogenicity; superior efficacy | Projected market leader by 2035 |

Application Notes & Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Traditional Murine Hybridoma Generation for Monoclonal Antibody Production

This protocol outlines the classic method for generating monoclonal antibodies, which remains a foundational technique for obtaining antibodies with native pairing [8].

Reagents & Equipment:

- Immunogen (purified protein, peptide, or cells)

- Adjuvant (e.g., Complete and Incomplete Freund's Adjuvant)

- Female BALB/c mice (6-8 weeks old)

- Myeloma cell line (e.g., SP2/0 or P3X63Ag8.653)

- Polyethylene glycol (PEG) solution for fusion

- HAT (Hypoxanthine-Aminopterin-Thymidine) selection medium

- HT (Hypoxanthine-Thymidine) medium

- ELISA plates and coating buffers for screening

- Cell culture flasks and COâ‚‚ incubator

Procedure:

- Immunization: Emulsify 10-100 µg of immunogen with an equal volume of Freund's Complete Adjuvant. Administer the emulsion intraperitoneally to mice. Perform two booster immunizations at 2-3 week intervals using immunogen emulsified with Incomplete Freund's Adjuvant. Test serum titers by ELISA 7-10 days after the final boost.

- Cell Preparation & Fusion: 3-4 days after a final booster immunization, sacrifice the mouse with the highest serum titer and aseptically remove the spleen. Prepare a single-cell suspension of splenocytes in serum-free medium. Culture the myeloma cells to ensure they are in log-phase growth. Mix splenocytes and myeloma cells at a 10:1 ratio and pellet by centrifugation. Slowly add 1 mL of 50% PEG 1500 to the cell pellet over 1 minute with gentle agitation. Slowly dilute the PEG with serum-free medium over 5-7 minutes.

- HAT Selection & Cloning: Resuspend the fused cells in HAT medium supplemented with 20% Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS) and plate into 96-well tissue culture plates. Incubate at 37°C in a 5% CO₂ humidified incubator. Feed cells with HAT medium every 3-4 days. After 10-14 days, screen supernatant from wells with hybridoma growth for desired antigen specificity by ELISA. Perform at least two rounds of limiting dilution subcloning of positive wells to ensure monoclonality, using HT medium during the first subcloning.

- Expansion & Characterization: Expand stable, monoclonal hybridoma lines. Isotype the produced antibody. Cryopreserve positive clones in liquid nitrogen for long-term storage.

Protocol 2: AI-DrivenDe NovoAntibody Design andIn VitroValidation

This protocol describes a modern computational workflow for generating and validating novel antibody sequences, leveraging powerful AI models like RFdiffusion and ProteinMPNN [10] [11].

Reagents & Equipment:

- High-performance computing (HPC) cluster with GPU acceleration

- AI/ML Software: RFdiffusion [10], ProteinMPNN [10], AlphaFold2 [10] or similar (ESM-IF, Chai-2 [11])

- Target antigen structure (experimental or AlphaFold2-predicted)

- Gene synthesis service

- Mammalian expression system (e.g., HEK293 or CHO cells)

- Biacore or Octet system for binding kinetics

- UPLC-SEC for aggregation analysis

Procedure:

- Target Featurization and Scaffold Specification: Input the 3D structure of the target antigen (e.g., from PDB or an AlphaFold2 prediction) into the design platform. Define design constraints, including the desired epitope region and any specific structural scaffolds for the antibody (e.g., a particular IgG subclass framework).

- Paratope and Backbone Generation: Use a diffusion model (e.g., RFdiffusion) to generate novel protein backbones that are complementary to the target epitope. This model samples the conformational landscape to create binders inspired by, but distinct from, natural antibodies [10].

- Sequence Design with Inverse Folding: For each generated backbone, use an inverse folding algorithm such as ProteinMPNN or ESM-IF to design a amino acid sequence that is most likely to fold into that specific structure. These tools achieve a high sequence recovery rate (~53%), significantly improving on older physics-based methods [10].

- In Silico Ranking and Filtering: Score the designed antibody sequences using models that predict affinity, stability, and developability (e.g., solubility, low polyspecificity). Filter the thousands of in silico designs down to the top 10-50 candidates for synthesis based on these scores. This step can achieve a hit rate of 15.5% or higher in subsequent testing [11].

- Gene Synthesis, Expression, and In Vitro Validation: Outsource the coding sequences of the top candidates for gene synthesis. Clone the genes into an mammalian expression vector, transiently transfect HEK293 cells, and purify the expressed antibodies using protein A/G chromatography. Validate the designs experimentally:

- Binding Kinetics: Determine affinity (KD) and kinetics (kon, koff) using surface plasmon resonance (SPR) or bio-layer interferometry (BLI).

- Specificity: Test binding to the target antigen versus unrelated proteins via ELISA.

- Developability: Assess stability under stressed conditions (e.g., thermal shift assay) and measure aggregation propensity by UPLC-SEC.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Antibody Discovery and Engineering

| Research Reagent / Solution | Function & Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|

| Phage Display Library [8] [12] | A diverse collection of bacteriophages displaying antibody fragments (e.g., scFv, Fab) used for in vitro selection of binders. | High diversity (>10^10 unique clones); enables discovery without animal immunization. |

| Hybridoma Fusion Partner Cell Line [8] | An immortal myeloma cell line (e.g., SP2/0) deficient in HGPRT, used for fusion with B-cells to create immortal hybridomas. | Enzyme-deficient for selection with HAT medium; high fusion efficiency. |

| HAT/HT Selection Media [8] | A critical cell culture supplement for selecting successfully fused hybridomas and eliminating unfused myeloma cells post-electrofusion. | Contains Hypoxanthine, Aminopterin, and Thymidine; Aminopterin blocks the de novo synthesis pathway. |

| AI-Driven Drug Discovery Platform (e.g., BioNeMo, Chai Discovery) [13] [11] | Integrated computational environments using generative AI and ML models for de novo antibody design and optimization. | Models like RFdiffusion and ProteinMPNN; enables in silico affinity maturation and developability prediction. |

| Microfluidic Single B-Cell Screening System [8] [13] | A high-throughput platform for isolating, analyzing, and sequencing individual antigen-specific B-cells from immunized animals or convalescent patients. | Preserves native VH-VL pairing; allows for rapid recovery of full-length antibody sequences. |

| 2-Carboxyphenol-d4 | Salicylic Acid-d4 | Certified Reference Standard | Salicylic Acid-d4 is an internal standard for LC/MS or GC/MS applications in pharmaceutical and clinical research. This product is for research use only and not for human use. |

| 6-Chloro-1,3,5-triazine-2,4-diamine-13C3 | 6-Chloro-1,3,5-triazine-2,4-diamine-13C3, CAS:1216850-33-7, MF:C3H4ClN5, MW:148.53 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Workflow Visualization

The following diagrams, created using Graphviz DOT language, illustrate the logical relationships and experimental workflows central to the evolution of antibody discovery.

Diagram Title: Traditional Hybridoma Generation Workflow

Diagram Title: Modern AI-Driven Antibody Discovery Workflow

Diagram Title: The Shift in Antibody Discovery Paradigms

The discovery and optimization of therapeutic antibodies, a cornerstone of modern biologics, have traditionally relied on experimental methods such as animal immunization and display technologies. These approaches, while effective, are often time-consuming, labor-intensive, and limited in their ability to explore the vast sequence space of antibodies [10]. The field is now undergoing a profound transformation driven by computational advances. The integration of high-accuracy protein structure prediction tools like AlphaFold2 with sophisticated machine learning (ML) models is breaking long-standing design barriers, enabling the rapid in silico design of antibodies with tailored properties [14] [15]. This document details the specific applications and experimental protocols underpinning this computational leap, providing a framework for its implementation in therapeutic antibody research.

Core Computational Technologies

Revolutionizing Structure Prediction with AlphaFold2

AlphaFold2 represents a fundamental shift in computational biology, providing the first method capable of regularly predicting protein structures with atomic accuracy, even in the absence of homologous structures [16]. Its architecture is uniquely suited to addressing challenges in antibody design.

Key Architectural Innovations of AlphaFold2:

- Evoformer: A novel neural network block that processes inputs through repeated layers, operating on both a multiple sequence alignment (MSA) representation and a pair representation. It enables continuous information exchange between the evolutionary (MSA) and spatial (pair) data streams [16].

- Structure Module: This module introduces an explicit 3D structure, initialized from a trivial state and rapidly refined into a highly accurate atomic model. It employs an equivariant transformer to reason about side-chain atoms and uses a loss function that emphasizes the orientational correctness of residues [16].

- Iterative Refinement (Recycling): The network's output is recursively fed back into the same modules, allowing for iterative refinement that significantly enhances prediction accuracy [16].

For antibody researchers, the resulting explosion of reliably predicted structures—from approximately 200,000 in the Protein Data Bank (PDB) to over 200 million in the AlphaFold database—has dramatically expanded the number of viable starting templates for design projects [10].

Machine Learning for Sequence Design and Optimization

Complementing the structural revolution, machine learning models are revolutionizing how antibody sequences are designed and optimized. These approaches can be broadly categorized as follows:

- Unsupervised & Generative Models: Trained on massive datasets of protein or antibody sequences (e.g., from the Observed Antibody Space (OAS) database), these models learn the underlying principles of "natural" or "fit" sequences [14] [17]. They can then generate novel antibody sequences with native-like biophysical properties, such as high stability. For instance, autoregressive models have been used to design nanobody libraries with 1000-fold greater expression than conventional methods [14].

- Supervised & Bayesian Optimization Models: These models are fine-tuned on experimental data (e.g., binding affinity measurements from yeast display) to predict specific extrinsic properties. A notable end-to-end Bayesian framework has been demonstrated to design single-chain variable fragment (scFv) libraries where 99% of the variants showed improved binding over the initial candidate, representing a 28.7-fold improvement over directed evolution in a head-to-head comparison [15].

Table 1: Key Machine Learning Model Types in Antibody Engineering

| Model Type | Training Data | Primary Function | Example Application/Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protein Language Models (e.g., BERT) | Broad protein sequence databases (e.g., UniRef) | Predict evolutionarily likely mutations | Affinity maturation of anti-viral antibodies, achieving up to 160-fold affinity improvement [14] |

| Antibody-Specific Language Models | Antibody-specific sequence repertoires (e.g., OAS) | Generate stable, native-like antibody sequences | Design of highly stable nanobody libraries with high expression yields [14] |

| Bayesian Optimization Models | High-throughput binding affinity data | Design high-affinity binders with uncertainty quantification | Generation of diverse scFv libraries where nearly all variants are improvements over the parent candidate [15] |

Application Notes: Integrated Computational Workflows

Workflow 1: De Novo Binder Design

This protocol describes a structure-centric approach for designing novel antibody binders from scratch, leveraging structure prediction and de novo design tools.

Diagram 1: De novo binder design workflow

Detailed Protocol:

- Generate Target Antigen Structure: For antigens with unknown structure, use AlphaFold2 to predict a high-confidence 3D model [10].

- De Novo Backbone Design: Use a diffusion-based model like RFDiffusion to generate novel protein backbones that are structurally complementary to the target antigen's epitope. The process can be constrained with a given active site or binding partner motif [10].

- Sequence Design for Backbone: Using the generated backbone as a fixed scaffold, employ inverse folding tools such as ProteinMPNN or ESM-IF to design a sequence that is most likely to fold into that structure. These tools use graph-based architectures to model residue microenvironments and achieve sequence recovery rates of over 50% [10].

- In silico Validation:

- Self-Consistency Check: Predict the structure of the designed sequence using AlphaFold2 and align it to the designed backbone. A high degree of similarity increases confidence.

- Interaction Validation: Use AlphaFold-Multimer or similar tools to co-fold the designed binder with the target antigen. While this remains a challenging task, it can provide insights into the binding mode and interface [10].

- Experimental Validation: Synthesize the top-ranking designs and characterize them experimentally for expression, stability, and binding affinity.

Workflow 2: ML-Driven Affinity Maturation

This protocol outlines a data-driven, sequence-centric approach for enhancing the affinity of an existing antibody candidate, bypassing the need for explicit structural information.

Diagram 2: ML-driven affinity maturation workflow

Detailed Protocol:

- Generate High-Throughput Training Data:

- Method: Use a yeast mating assay or phage display to screen a library of random mutants (e.g., k=1, 2, 3 mutations within CDRs) of your candidate antibody.

- Output: Quantify binding affinity for tens of thousands of variants, creating a labeled dataset linking sequence to function [15].

- Pre-train a Language Model: Utilize a transformer-based language model (e.g., BERT) that has been pre-trained on a large corpus of protein sequences (Pfam) or, preferably, antibody-specific sequences (OAS database). This provides the model with a foundational understanding of protein biochemistry [15].

- Supervised Fine-Tuning: Fine-tune the pre-trained language model on the experimental binding data generated in Step 1. The model learns to predict binding affinity from sequence. Use an ensemble or Gaussian Process method to provide uncertainty estimates for the predictions [15].

- Bayesian Optimization for Library Design:

- Construct a fitness landscape that maps any antibody sequence to its posterior probability of having better affinity than the parent.

- Use sampling algorithms (e.g., Gibbs sampling, Genetic Algorithms) to explore this landscape and propose sequences that maximize the fitness function. Gibbs sampling is particularly effective for generating highly diverse candidates [15].

- Experimental Validation: Synthesize the computationally designed library (e.g., ~10^4 sequences) and test it empirically using the same high-throughput assay from Step 1.

Table 2: Key Performance Metrics from Recent ML-Driven Antibody Engineering Studies

| Study Focus | Method | Key Comparative Result | Diversity Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| scFv Affinity Maturation [15] | Bayesian Optimization + Language Models | 28.7-fold improvement in binding over directed evolution | >99% of designed scFvs were improvements over candidate |

| Anti-Virus Antibody Affinity [14] | Protein Language Models (Unsupervised) | Up to 160-fold binding affinity improvement | Successful with small sets of mutations (~10-20) |

| Nanobody Stability & Expression [14] | Generative Autoregressive Model | 1000-fold greater library expression than conventional design | Generated diverse set of ~185,000 CDR3 sequences |

Table 3: Key Reagents and Resources for Computational Antibody Design

| Resource Category | Name | Function & Application |

|---|---|---|

| Key Software & Algorithms | AlphaFold2 / AlphaFold-Multimer [16] [10] | Predicts 3D structures of monomeric proteins and protein complexes from sequence. |

| RFDiffusion [10] | Generative model for creating novel protein backbones, constrained by motifs or binding partners. | |

| ProteinMPNN / ESM-IF [10] | Inverse folding tools that design sequences for a given protein backbone structure. | |

| Rosetta [10] | Suite for biomolecular modeling and design, using energy functions for structure prediction and design. | |

| Critical Databases | Structural Antibody Database (SAbDab) [17] | Curated, up-to-date repository of all publicly available antibody and nanobody structures. |

| Observed Antibody Space (OAS) [15] [17] | Massive collection of annotated antibody sequence data from next-generation sequencing studies. | |

| Theraputic Antibody Databases (e.g., TABS, SAbDab-Therapeutic) [17] | Curate information on clinically investigated and approved antibody therapeutics. | |

| Experimental Systems for Data Generation | Yeast Display [15] | High-throughput platform for screening antibody libraries and generating quantitative binding data for ML models. |

| Phage Display [10] [15] | Well-established technology for selecting binders from large libraries, often used for initial candidate discovery. |

Critical Challenges and Future Directions

Despite significant progress, several challenges must be addressed to fully realize the potential of computational antibody design.

- Data Quality and Volume: A primary bottleneck is the scarcity of large, diverse, and high-quality experimental datasets for training and validation. Current datasets are often small and skewed (e.g., over half the mutations in one major database are alanine scans), leading models to overfit and fail to generalize [18]. Robust AI models require not just more data, but more varied data—with estimates suggesting a need for at least 90,000 experimentally measured mutations for generalizable predictions [18].

- Antibody-Antigen Co-Folding: Accurately predicting the complex structure of an antibody bound to its antigen remains a formidable challenge. Performance of tools like AlphaFold-Multimer on antibody-antigen interactions is still variable and requires improvement [10].

- Multiparameter Optimization: While affinity is a key goal, therapeutic antibodies also require optimal developability properties (e.g., low immunogenicity, high solubility, low viscosity). Integrating predictive models for these multiple parameters into a single design framework is an active area of research.

The convergence of accurate structure prediction, powerful generative models, and high-throughput experimental validation is ushering in a new era for therapeutic antibody development. By adopting the protocols and resources outlined in this document, researchers can leverage these computational leaps to accelerate the design of better, safer, and more effective antibody therapeutics.

The field of protein engineering is undergoing a revolutionary transformation through the integration of generative artificial intelligence (AI). These advanced computational tools enable the de novo design of protein structures and functions with precision that now rivals or even surpasses nature's capabilities [19]. For researchers focused on therapeutic antibody development, two platforms have emerged as particularly transformative: RFdiffusion for protein backbone generation and ProteinMPNN for sequence design. These tools operate synergistically within a comprehensive design pipeline that begins with structural blueprints and concludes with functionally optimized sequences, offering unprecedented control over protein therapeutics design.

RFdiffusion represents a fundamental advancement as a generative model for protein backbones based on denoising diffusion probabilistic models. By fine-tuning the RoseTTAFold structure prediction network on protein structure denoising tasks, RFdiffusion achieves outstanding performance across diverse design challenges including unconditional protein monomer design, protein binder design, and symmetric oligomer design [20]. The methodology initializes random residue frames and iteratively denoises them through multiple steps, progressively refining the structure toward realistic protein architectures. This approach enables researchers to generate elaborate protein structures with minimal overall structural similarity to naturally occurring proteins in the Protein Data Bank, demonstrating considerable generalization beyond known structural space [20].

Complementing RFdiffusion, ProteinMPNN (Protein Message Passing Neural Network) serves as a deep-learning-based protein sequence design method that operates on fixed protein backbones. Whereas traditional physicochemical energy functions often struggle with the combinatorial complexity of sequence space, ProteinMPNN leverages neural network architectures to rapidly generate optimal sequences for given structural scaffolds. The network treats protein residues as nodes in a graph, with edges defined by Cα–Cα distances, and encodes backbone geometry through pairwise distances between key atoms [21]. This architecture enables high-speed sequence design that scales linearly with protein length, making it practical for designing large protein complexes and libraries for experimental screening.

RFdiffusion: Architectural Framework and Mechanisms

RFdiffusion employs a sophisticated diffusion model framework that builds upon the foundational principles of RoseTTAFold. The system represents protein backbones using a frame representation that includes a Cα coordinate and N-Cα-C rigid orientation for each residue [20]. During training, the model learns to reverse a structured noising process applied to protein structures from the Protein Data Bank. The noising schedule corrupts structures over up to 200 steps through two primary mechanisms: Cα coordinates are perturbed with 3D Gaussian noise, while residue orientations are disturbed using Brownian motion on the manifold of rotation matrices [20].

A critical innovation in RFdiffusion is its implementation of self-conditioning, a training strategy inspired by recycling in AlphaFold2. Unlike canonical diffusion models where predictions at each timestep are independent, self-conditioning allows the model to condition on previous predictions between timesteps [20]. This approach significantly enhances performance on in silico benchmarks for both conditional and unconditional protein design tasks by increasing the coherence of predictions within denoising trajectories. The model is trained using a mean-squared error loss between frame predictions and true protein structures without alignment, which promotes continuity of the global coordinate frame between timesteps—a crucial distinction from the frame aligned point error loss used in standard RoseTTAFold training [20].

For therapeutic antibody design, researchers have developed a specialized version of RFdiffusion fine-tuned specifically on antibody complex structures [22]. This variant incorporates several key modifications: (1) the antibody framework sequence and structure can be provided as conditioning input, enabling designs that maintain stable scaffold regions while innovating in complementarity-determining regions (CDRs); (2) the framework structure is provided in a global-frame-invariant manner using the template track of RFdiffusion, which encodes pairwise distances and dihedral angles as a 2D matrix; and (3) one-hot encoded "hotspot" features allow specification of epitope residues, directing the designed CDRs toward targeted binding regions [22].

ProteinMPNN and Its Specialized Variants

ProteinMPNN represents a fundamental shift from physics-based sequence design methods toward deep learning approaches. The core architecture employs an encoder-decoder framework where protein residues are treated as nodes in a graph, with edges connecting residues based on Cα–Cα distances [21]. The encoder processes input features through multiple message-passing layers that capture both local and long-range interactions within the protein structure. A key advantage of ProteinMPNN is its use of random autoregressive decoding, which enables the design of symmetric complexes and multistate proteins by sequentially generating residues while accounting for previously designed positions [21].

The introduction of LigandMPNN has extended ProteinMPNN's capabilities to explicitly model interactions with nonprotein components—a critical requirement for designing functional antibodies, enzymes, and biosensors [21]. LigandMPNN incorporates several architectural innovations: (1) a protein-ligand graph with edges between protein residues and nearby ligand atoms (within ~10Å); (2) fully connected ligand graphs for each protein residue to enrich representation of ligand geometry; and (3) additional encoder layers dedicated to processing protein-ligand interactions [21]. This architecture significantly outperforms both Rosetta and standard ProteinMPNN on native backbone sequence recovery for residues interacting with small molecules (63.3% versus 50.4% and 50.5%), nucleotides (50.5% versus 35.2% and 34.0%), and metals (77.5% versus 36.0% and 40.6%) [21].

For therapeutic applications, CAPE-Beam represents another specialized decoding strategy for ProteinMPNN that addresses immunogenicity concerns [23]. This approach minimizes cytotoxic T-lymphocyte immunogenicity risk by constraining designs to only include peptide fragments (kmers) that are either predicted not to be presented to CTLs or are subject to central tolerance mechanisms. This capability is particularly valuable for engineering therapeutic proteins intended for chronic administration or broad patient populations where immune responses could limit efficacy or cause adverse effects [23].

Figure 1: Integrated computational workflow for de novo antibody design using RFdiffusion and ProteinMPNN. The pipeline begins with structural generation, proceeds through sequence optimization, and concludes with validation and affinity maturation.

Quantitative Performance Benchmarks

Structure Generation and Sequence Recovery Metrics

Table 1: Performance comparison of RFdiffusion and ProteinMPNN against established methods across key protein design tasks

| Design Task | Method | Performance Metric | Result | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Small molecule-binding proteins | LigandMPNN | Sequence recovery (residues within 5Ã…) | 63.3% | [21] |

| Small molecule-binding proteins | ProteinMPNN | Sequence recovery (residues within 5Ã…) | 50.4% | [21] |

| Small molecule-binding proteins | Rosetta (genpot) | Sequence recovery (residues within 5Ã…) | 50.4% | [21] |

| Nucleotide-binding proteins | LigandMPNN | Sequence recovery (residues within 5Ã…) | 50.5% | [21] |

| Nucleotide-binding proteins | ProteinMPNN | Sequence recovery (residues within 5Ã…) | 34.0% | [21] |

| Nucleotide-binding proteins | Rosetta (DNA-optimized) | Sequence recovery (residues within 5Ã…) | 35.2% | [21] |

| Metal-binding proteins | LigandMPNN | Sequence recovery (residues within 5Ã…) | 77.5% | [21] |

| Metal-binding proteins | ProteinMPNN | Sequence recovery (residues within 5Ã…) | 40.6% | [21] |

| Metal-binding proteins | Rosetta | Sequence recovery (residues within 5Ã…) | 36.0% | [21] |

| Unconditional monomer generation | RFdiffusion | In silico success rate* | High (300-600 residue proteins) | [20] |

| Antibody design | Fine-tuned RFdiffusion | Experimental validation (VHH binders) | 4 disease-relevant epitopes targeted | [22] |

In silico success defined as AF2 structure with mean pAE <5, global backbone RMSD <2Ã…, and <1Ã… RMSD on scaffolded functional sites [20]

The performance advantages of LigandMPNN over traditional sequence design methods are particularly pronounced for metal-binding sites, where it more than doubles the sequence recovery rate of both Rosetta and ProteinMPNN [21]. This substantial improvement highlights the importance of explicitly modeling nonprotein atomic context when designing functional sites. The model's performance remains consistently superior across most proteins in validation datasets, with variations likely reflecting differences in crystal structure quality and native amino acid composition at binding sites [21].

RFdiffusion demonstrates remarkable capability in generating diverse protein topologies spanning alpha, beta, and mixed alpha-beta structures. The designs are not only structurally novel but also highly designable, as evidenced by AlphaFold2 and ESMFold predictions that closely match design models even for large proteins up to 600 residues [20]. Experimental characterization of several designed proteins revealed circular dichroism spectra consistent with design models and exceptional thermostability, confirming the practical utility of these computational designs [20].

Experimental Success in Therapeutic Antibody Design

Table 2: Experimentally validated antibody designs generated using RFdiffusion and ProteinMPNN

| Target Antigen | Antibody Format | Experimental Validation | Affinity (Kd) | Key Structural Validation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Influenza haemagglutinin | VHH (single-domain) | Yeast display, SPR, Cryo-EM | Initial: tens-hundreds nMMatured: single-digit nM | Cryo-EM confirms designed binding poseHigh-resolution structure verifies atomic accuracy of CDRs |

| Clostridium difficile toxin B (TcdB) | VHH (single-domain) | E. coli expression, SPR, Cryo-EM | Initial: tens-hundreds nM | Cryo-EM confirms designed binding pose |

| Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) sites I & III | VHH (single-domain) | Yeast surface display | Not specified | Binding confirmation at specified sites |

| SARS-CoV-2 RBD | VHH (single-domain) | Yeast surface display | Not specified | Binding confirmation |

| IL-7Rα | VHH (single-domain) | E. coli expression, SPR | Initial: tens-hundreds nM | Binding confirmation |

| TcdB | scFv (single-chain) | Cryo-EM | Not specified | Cryo-EM confirms binding poseHigh-resolution data verifies all 6 CDR loops |

| PHOX2B peptide–MHC complex | scFv (single-chain) | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified |

The experimental success of AI-designed antibodies represents a landmark achievement in computational protein design. For therapeutic antibody development, the fine-tuned RFdiffusion model has enabled targeting of diverse disease-relevant epitopes across viral pathogens, bacterial toxins, and immune signaling molecules [22]. Although initial computational designs typically exhibit modest affinities in the tens to hundreds of nanomolar range, subsequent affinity maturation using systems like OrthoRep can improve binding to single-digit nanomolar levels while maintaining epitope specificity [22].

The structural validation of designed antibodies is particularly noteworthy. Cryo-electron microscopy confirmed that designed VHHs targeting influenza haemagglutinin and Clostridium difficile toxin B bind in precisely the intended poses [22]. Even more impressively, high-resolution structure determination verified atomic accuracy of the designed complementarity-determining regions—a level of precision that was previously unimaginable for de novo antibody design. For single-chain variable fragments (scFvs) targeting TcdB, structural analysis confirmed the accurate design of all six CDR loop conformations [22].

Protocol: De Novo Antibody Design Pipeline

Stage 1: Structure Generation with Fine-Tuned RFdiffusion

Materials and Reagents:

- Target protein structure (PDB format or AlphaFold2 prediction)

- Specified epitope residues on target

- Antibody framework structure (e.g., h-NbBcII10FGLA for VHHs) [22]

- Computing resources: High-performance GPU cluster

- Software: RFdiffusion fine-tuned for antibody design [22]

Procedure:

- Input Preparation: Prepare the target protein structure and identify epitope residues for targeting. Select an appropriate antibody framework—for single-domain antibodies, the humanized VHH framework h-NbBcII10FGLA has proven effective [22].

Framework Conditioning: Provide the framework structure as conditioning input to RFdiffusion using the template track. This encodes the framework as a 2D matrix of pairwise distances and dihedral angles, preserving its structural integrity while allowing CDR innovation [22].

Epitope Specification: Designate epitope residues using one-hot encoded "hotspot" features to direct CDR interactions toward the target site. This ensures the generated antibodies specifically engage the desired epitope [22].

Structure Generation: Execute RFdiffusion sampling starting from random noise. The self-conditioning mechanism will iteratively denoise the structure over multiple steps (typically 200), progressively refining CDR loops and antibody orientation relative to the target [20] [22].

Initial Filtering: Select generated antibody structures that maintain framework integrity while exhibiting diverse CDR conformations that complement the target epitope topology.

Stage 2: Sequence Design with LigandMPNN

Materials and Reagents:

- Generated antibody backbone structures from RFdiffusion

- Target structure with specified epitope

- Computing resources: Standard CPU or GPU

- Software: LigandMPNN [21]

Procedure:

- Input Configuration: Prepare the complex structure containing the generated antibody backbone and target protein. Ensure all nonprotein atoms (including key functional groups at the epitope) are included in the input structure.

Context Atom Selection: LigandMPNN automatically selects the 25 closest ligand atoms to each protein residue based on virtual Cβ and ligand atom distances. Verify appropriate context inclusion for CDR residues [21].

Sequence Design: Execute LigandMPNN using random autoregressive decoding to generate sequences. Sample multiple sequences (typically 8-10) per backbone to explore sequence space while maintaining structural compatibility [20] [21].

Sidechain Packing: Utilize LigandMPNN's integrated sidechain packing network to predict optimal sidechain conformations. The network predicts mixture distributions for chi angles and decodes them autoregressively to generate physically realistic rotamer placements [21].

Stage 3: Validation and Affinity Maturation

Materials and Reagents:

- Fine-tuned RoseTTAFold2 for antibody structure prediction [22]

- Rosetta software suite for ddG calculations

- Yeast display system for experimental screening [22]

- OrthoRep system for in vivo affinity maturation [22]

Procedure:

- Computational Validation:

- Use fine-tuned RF2 to predict structures of designed antibody-antigen complexes. This specialized RF2 variant incorporates target structure and epitope information during prediction to enhance accuracy [22].

- Filter designs where predicted structures closely match designed models (backbone RMSD <2Ã…) and exhibit high interface quality (Rosetta ddG).

Experimental Screening:

- Clone designed antibody sequences into yeast display vectors.

- Screen libraries for target binding using fluorescence-activated cell sorting.

- Isplicate and characterize binding clones using surface plasmon resonance to determine affinity and specificity [22].

Affinity Maturation:

- For initial binders with modest affinity (tens to hundreds of nM), implement affinity maturation using OrthoRep continuous evolution system [22].

- Screen matured libraries for improved binders while maintaining epitope specificity.

- Characterize optimized antibodies using structural methods (cryo-EM, X-ray crystallography) to verify binding mode preservation [22].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key research reagents and computational tools for AI-driven antibody design

| Category | Item | Specification/Format | Function in Workflow |

|---|---|---|---|

| Computational Models | RFdiffusion (antibody fine-tuned) | Python/PyTorch implementation | De novo generation of antibody structures with targeted CDRs |

| ProteinMPNN/LigandMPNN | Python implementation | Sequence design for structural scaffolds with ligand context | |

| Fine-tuned RoseTTAFold2 | Python implementation | Structure prediction validation for antibody-antigen complexes | |

| Antibody Frameworks | h-NbBcII10FGLA | VHH framework structure | Humanized single-domain antibody scaffold for VHH designs |

| Therapeutic scFv frameworks | Structure files | Stable single-chain variable fragment scaffolds | |

| Experimental Systems | Yeast display system | Saccharomyces cerevisiae | High-throughput screening of antibody binding |

| OrthoRep evolution system | Yeast-based | In vivo affinity maturation without throughput bottlenecks | |

| Surface plasmon resonance | Biacore or similar | Quantitative binding affinity measurements | |

| Structural Validation | Cryo-electron microscopy | Frozen-hydrated samples | Structural validation of antibody-antigen complexes |

| X-ray crystallography | Crystallized complexes | High-resolution structural verification | |

| 7-Hydroxy amoxapine-d8 | 7-Hydroxy amoxapine-d8, CAS:1189671-27-9, MF:C17H16ClN3O, MW:321.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Cycloguanil-d4hydrochloride | Cycloguanil-d4hydrochloride, MF:C11H15Cl2N5, MW:292.20 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

The integration of specialized computational tools with appropriate experimental systems creates a powerful pipeline for de novo antibody development. The fine-tuned RFdiffusion model enables targeted exploration of structural space, while LigandMPNN ensures optimal sequence compatibility with both the antibody structure and antigen interface [21] [22]. The inclusion of orthogonal validation methods, particularly the antibody-optimized RoseTTAFold2, provides crucial computational filtering before resource-intensive experimental testing [22].

For therapeutic development, the use of well-characterized humanized frameworks like h-NbBcII10FGLA reduces immunogenicity risks while providing stable structural scaffolds for CDR innovation [22]. Combined with high-throughput screening using yeast display and subsequent affinity maturation through OrthoRep, this toolkit enables rapid development of high-affinity therapeutic antibodies against virtually any target epitope [22].

Troubleshooting and Technical Considerations

Common Challenges and Solutions

Low Success Rates in Initial Design Generation:

- Problem: Insufficient diversity in generated CDR conformations or failure to engage target epitope.

- Solution: Adjust the hotspot residue weighting in RFdiffusion inputs to more strongly bias sampling toward the target epitope. Increase the number of design samples to explore broader structural space [22].

Poor Expression or Aggregation of Designed Antibodies:

- Problem: Designed sequences exhibit poor solubility or expression yields.

- Solution: Implement CAPE-Beam decoding strategy with ProteinMPNN to minimize immunogenicity risk and improve biophysical properties [23]. Incorporate aggregation prediction tools during sequence filtering.

Inaccurate Structure Predictions for Validation:

- Problem: Standard AlphaFold2 fails to accurately model antibody-antigen complexes, complicating computational validation [22].

- Solution: Utilize the fine-tuned RoseTTAFold2 specifically trained on antibody structures with epitope information. This specialized model significantly outperforms general-purpose structure prediction for antibody validation [22].

Moderate Affinity in Initial Designs:

- Problem: Initial designed antibodies show binding in the hundreds of nM range, insufficient for therapeutic applications.

- Solution: Implement orthogonal affinity maturation systems like OrthoRep that can efficiently explore sequence space around initial hits while maintaining epitope specificity [22].

Advanced Applications and Future Directions

The integration of RFdiffusion and ProteinMPNN has opened new frontiers in therapeutic protein design beyond conventional antibodies. Recent advances demonstrate the capability to design single-chain variable fragments (scFvs) with all six CDR loops designed de novo, as validated by cryo-EM structures showing atomic accuracy across all complementarity-determining regions [22]. This capability significantly expands the design space for therapeutic binders.

For enzyme design and small-molecule targeting, LigandMPNN enables precise engineering of binding pockets that explicitly consider the chemical properties of nonprotein components [21]. The method's ability to recover native-like sequences for metal-binding sites (77.5% recovery) far surpasses traditional computational approaches, highlighting its potential for designing metalloenzymes and catalytic antibodies [21].

The emerging paradigm of generative AI beyond natural diversity points toward even more ambitious applications. Protein language models trained on natural sequences can now generate synthetic proteins that maintain structural and functional coherence while exhibiting properties not found in nature [19]. As one researcher noted, "These AI models are trained with all known protein sequences on earth and learn the internal language or 'grammar' of proteins. Using this grammar, they are able to speak this language perfectly, generating completely new proteins that maintain structural and functional meaning" [19].

For the therapeutic antibody field specifically, these advances suggest a future where customized antibodies can be designed against virtually any target epitope with atomic-level precision, potentially revolutionizing treatment development for infectious diseases, cancer, and autoimmune disorders. The open availability of these tools on platforms like GitHub ensures widespread access, while commercial development through biotech companies like Xaira Therapeutics promises to translate these computational advances into clinical therapies [24].

The Engineer's Toolkit: Rational Design, Directed Evolution, and Display Technologies

Rational protein design represents a pivotal strategy in modern protein engineering, enabling the precise development of therapeutics with enhanced properties. This approach relies on the fundamental principle of establishing a structure-function relationship, frequently via molecular modeling techniques, to guide controllable amino acid sequence changes [25]. In the context of therapeutic antibody research, rational design provides a powerful methodology for improving affinity, specificity, stability, and reducing immunogenicity [8]. Unlike directed evolution, which introduces random mutations, rational design utilizes detailed structural knowledge—including amino acid sequences, three-dimensional structures, and mechanistic functional data—to inform targeted modifications via site-directed mutagenesis [25] [26]. The integration of advanced computational tools, such as artificial intelligence and machine learning for structure prediction, has significantly accelerated the design process, allowing for more efficient and predictive engineering of antibody-based therapeutics [8] [26].

Core Principles and Workflow

The overarching goal of rational protein design is to confer desired properties—such as enhanced thermostability, modified binding affinity, or increased solubility—through targeted genetic alterations. The general workflow is iterative, cycling through design, mutagenesis, expression, and characterization phases until the desired functional outcome is achieved [25]. The critical first step involves acquiring a high-resolution structure of the target protein, determined through methods like X-ray crystallography, cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM), or nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy [27] [25] [28]. Computational-aided design (CAD) is then employed to analyze the structure and identify specific amino acid residues for mutation that are predicted to improve function [25]. This is followed by the practical implementation of these changes through site-directed mutagenesis to create the variant genes, which are then expressed and purified [25]. Finally, the newly engineered proteins undergo rigorous characterization to validate that the designed properties have been successfully implemented [25].

The following diagram illustrates the logical and experimental workflow of a rational design cycle, from structural analysis to functional validation.

Key Experimental Protocols

The DiRect Site-Directed Mutagenesis Protocol

The Dimer-mediated Reconstruction by PCR (DiRect) method is an advanced SDM technique designed for high efficiency and minimal background. It is particularly suited for rational design-based protein engineering (RDPE) as it eliminates the need for laborious DNA cloning and sequencing steps typically required by conventional methods [29]. The protocol achieves nearly perfect mutation rates by employing a series of three consecutive PCR reactions to incorporate the mutation and reconstruct the full expression construct [29].

Primer Design for DiRect

- Mutagenesis Primers: Both forward and reverse primers are designed with a 5' half comprising a 21-nucleotide (nt) complementary sequence containing the mutation site in the middle. The 3' half consists of a 20-nt sequence that is complementary to the template plasmid [29].

- Reconstruction Primers: Standard primers are designed to bind outside the mutated region to amplify the full-length plasmid.

PCR Reaction Setup

The following table summarizes the components and conditions for the three PCR stages.

Table 1: Reaction Setup for DiRect Mutagenesis Protocol

| Component/Condition | Mutagenesis PCR (MutPCR) | Reconstruction PCR with Outer Primer (RecPCR-out) | Reconstruction PCR with Inner Primer (RecPCR-in) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Template | 5 ng of plasmid (e.g., pBK) | 2 µL of MutPCR product (unpurified) | 2 µL of RecPCR-out product (unpurified) |

| Primers | 0.5 µM each mutagenesis primer | 0.5 µM each reconstruction outer primer | 0.5 µM each reconstruction inner primer |

| Polymerase | KOD -Plus- Mutagenesis Polymerase | KOD -Plus- Mutagenesis Polymerase | KOD -Plus- Mutagenesis Polymerase |

| Total Volume | 20 µL | 20 µL | 20 µL |

| Thermal Cycling | 30 cycles of:• 98°C for 10 sec• 55°C for 30 sec• 68°C for 45 sec | 30 cycles of:• 98°C for 10 sec• 55°C for 30 sec• 68°C for 2 min | 30 cycles of:• 98°C for 10 sec• 55°C for 30 sec• 68°C for 2 min |

| Alexidine-d10 | Alexidine-d10, MF:C26H56N10, MW:518.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Bisphenol A-13C12 | Bisphenol A-13C12, CAS:263261-65-0, MF:C15H16O2, MW:240.20 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Post-PCR Processing

- Digestion: Following the RecPCR-in, the product is treated with DpnI to digest the methylated template plasmid.

- Transformation: The DpnI-treated product is directly used to transform competent E. coli cells.

- Verification: The mutation efficiency is exceptionally high. Colony PCR or sequencing of a few clones is sufficient to identify a correct mutant [29].

The technical workflow of the DiRect method, from initial amplification to final construct assembly, is depicted below.

Protocol for Dynamics Analysis via DEFMap

Understanding protein dynamics is crucial for rational design, as function is regulated by both tertiary structure and dynamic behavior [28]. The Dynamics Extraction From cryo-EM Map (DEFMap) method is a deep learning-based approach that quantitatively estimates local protein dynamics directly from cryo-EM density maps [28].

Procedure:

- Cryo-EM Map Preprocessing: Download the 3D cryo-EM density map from EMDB. Apply a 5 Ã… low-pass filter and unify the grid width to 1.5 Ã…/grid.

- Subvoxel Extraction: Extract local density data as subvoxels with grid lengths of 15 Ã…, centered on the position of existing heavy atoms in the corresponding atomic model (from PDB).

- Data Augmentation: Augment the dataset by rotating the subvoxels by 90° in the xy, xz, and yz planes.

- Model Application: Input the prepared subvoxels into the pre-trained 3D Convolutional Neural Network (3D CNN) model.

- Dynamics Prediction: The model outputs the predicted root-mean-square fluctuation (RMSF) values, which represent atomic fluctuations, providing quantitative dynamics information for the target protein.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Materials for Rational Protein Design

| Item | Function/Benefit in Rational Design | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| KOD -Plus- Mutagenesis Polymerase | High-fidelity DNA polymerase with proofreading activity, essential for accurate amplification in multi-step PCR mutagenesis. | DiRect mutagenesis protocol [29]. |

| Ile-δ1[13CH3]/Met-ε1[13CH3] (IM-labeling) | Isotopically labeled precursors for methyl-TROSY NMR; allow site-specific study of interactions and dynamics in large complexes. | Probing subunit interfaces in the 410 kDa RNA exosome complex [27]. |

| 4-trifluoromethyl-L-phenylalanine (tfmF) | Non-natural amino acid for 19F NMR spectroscopy; serves as a sensitive probe for local environment and dynamics, even in large assemblies. | Incorporation via amber codon suppression to study loop dynamics [27]. |

| TEMPO Spin Label | Paramagnetic label for Paramagnetic Relaxation Enhancement (PRE) NMR experiments; provides distance restraints. | Mapping proximity between subunits (e.g., Csl4 and Rrp41 entry loop) [27]. |

| DpnI Restriction Enzyme | Digests methylated parental DNA template, enriching for newly synthesized PCR product containing the desired mutation in bacterial transformation. | Post-PCR digestion in the DiRect protocol [29]. |

| Cell-Free Protein Synthesis (CF) System | Uses PCR-amplified linear DNA and cell extracts for rapid protein expression, omitting cloning and fermentation steps. | Coupling with DiRect for high-throughput screening of designed variants (DiRect-CF) [29]. |

| 4-(3,6-Dimethylhept-3-yl)phenol-13C6 | 4-(3,6-Dimethylhept-3-yl)phenol-13C6, CAS:1173020-38-6, MF:C15H24O, MW:226.31 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Secalciferol-d6 | Secalciferol-d6, CAS:1440957-55-0, MF:C27H44O3, MW:422.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Data Analysis and Interpretation

Quantitative Outcomes of Rational Design Strategies

The success of rational design and associated protocols is measured by quantitative changes in protein properties. The following table compiles key performance data from cited studies.

Table 3: Quantitative Data from Protein Engineering Studies

| Method / System | Key Performance Metric | Result / Value | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| DiRect-CF System [29] | Mutation Success Rate | Nearly 100% | Generation of thermostable 3-quinuclidinone reductase (RrQR) variants. |

| DiRect-CF System [29] | Total Process Time | ~1 day | From mutant gene design to protein analysis. |

| DEFMap [28] | Prediction Correlation (r) | 0.665 (±0.124) | Correlation between predicted and actual (MD-derived) dynamics (RMSF). |

| DEFMap [28] | Correlation from Raw Map Intensity | 0.459 (±0.179) | Baseline for DEFMap performance improvement. |

| Rational Design [8] | Marketed mAbs (FDA Approved) | 144 (as of Aug 2025) | Outcome of therapeutic antibody engineering. |

| Phage Display [8] | FDA-Approved Antibody Drugs | 16 | Platform for generating fully human antibodies. |

Application in Therapeutic Antibody Engineering

The principles of rational design are extensively applied in therapeutic antibody development. Key advancements include:

- Humanization: CDR grafting is used to convert murine antibodies into humanized versions, drastically reducing immunogenicity while retaining specificity. This approach produced the first approved humanized mAb, daclizumab, and the oncology blockbuster trastuzumab [8].

- Affinity Maturation: Structural knowledge of the antibody-antigen interface allows for targeted mutagenesis of CDR residues to enhance binding affinity.

- Effector Function Engineering: Rational design modifies the Fc region to tailor interactions with immune cells, optimizing mechanisms of action like Antibody-Dependent Cellular Cytotoxicity (ADCC) for specific therapeutic goals [8].

- Bispecific Antibodies (bsAbs): Rational design enables the engineering of bsAbs that can simultaneously bind two distinct antigens, for example, redirecting T cells to tumor cells [8]. The integration of AI and machine learning is now revolutionizing these processes, improving immunogenicity prediction and enabling more efficient optimization of candidate antibodies [8].

Directed evolution stands as a cornerstone of modern protein engineering, harnessing the principles of natural selection in a controlled laboratory setting to tailor biomolecules for specific, human-defined applications. This powerful, iterative process of genetic diversification and functional selection has been instrumental in advancing therapeutic antibody research, enabling the development of antibodies with enhanced affinity, specificity, and stability [30]. For researchers and drug development professionals, mastering these techniques is crucial for accelerating the discovery of next-generation biologics.

The fundamental cycle of directed evolution involves two critical steps: first, the creation of genetic diversity within a parent gene to generate a vast library of variants, and second, the high-throughput screening or selection of this library to identify individuals with improved functional properties [31] [30]. Among the various methods for library generation, error-prone PCR (epPCR) is a widely adopted technique for introducing random mutations, mimicking the spontaneous mutations that drive natural evolution. Successive rounds of mutagenesis and screening allow for the accumulation of beneficial mutations, leading to proteins with significantly optimized performance characteristics for therapeutic use [32] [30].

Key Methodologies in Directed Evolution

The success of a directed evolution campaign hinges on the strategic choice of methods for creating diversity and for identifying improved variants. The following sections detail the core techniques, with a specific focus on epPCR and common screening platforms used in antibody engineering.

Generating Diversity: Error-Prone PCR (epPCR)

Error-prone PCR (epPCR) is a robust method for introducing random point mutations across a gene sequence without requiring prior structural knowledge [30]. This technique is particularly valuable in the early stages of antibody engineering when the goal is to explore a wide sequence space to enhance properties like affinity or stability [32].

The core principle involves modifying standard PCR conditions to reduce the fidelity of the DNA polymerase, thereby increasing the error rate during DNA amplification [30]. This is achieved through several key adjustments:

- Polymerase Selection: Using a polymerase that lacks 3' to 5' proofreading activity, such as Taq polymerase.

- Metal Cofactor: Adding manganese ions (Mn²âº) to the reaction, which is a critical factor for promoting misincorporation of nucleotides.

- dNTP Imbalance: Creating unbalanced concentrations of the four deoxynucleotide triphosphates (dNTPs) to further encourage misincorporation [30].

The mutation rate can be finely tuned by adjusting the concentration of Mn²âº, with typical protocols aiming for 1–5 base substitutions per kilobase of DNA, resulting in an average of one or two amino acid changes per protein variant [30]. It is important to note that epPCR is not perfectly random; it exhibits a mutational bias favoring transition mutations (AG, CT) over transversion mutations, which limits the accessible amino acid substitutions at any given position to an average of 5.6 out of 19 possible alternatives [30].

Table 1: Key Components and Conditions for a Standard Error-Prone PCR Protocol

| Component | Function | Considerations for epPCR |

|---|---|---|

| Template DNA | Gene of interest (e.g., scFv, Fab) | Use high-purity, minimal amount to avoid wild-type carryover. |

| Primers | Flank the gene for amplification | Design to anneal to constant regions outside the variable domains. |

| Taq Polymerase | Amplifies DNA | Lacks proofreading; essential for incorporating errors. |

| MgClâ‚‚ | Essential polymerase cofactor | Concentration is often elevated (~7 mM) to reduce fidelity. |

| MnClâ‚‚ | Key fidelity reducer | Titrate (0.1-0.5 mM) to control mutation rate [30]. |

| dNTPs | Nucleotide building blocks | Use unbalanced concentrations (e.g., higher dATP, dTTP) to promote errors. |

| PCR Buffer | Provides optimal reaction conditions | Standard buffer is used, but Mg²⺠and Mn²⺠are added separately. |

Advanced Cloning Technique: Circular Polymerase Extension Cloning (CPEC)

Following epPCR, the mutated gene fragments must be cloned into an expression vector for screening. Traditional, restriction enzyme- and ligase-dependent cloning methods are inefficient and can lead to a significant loss of library diversity [33]. Circular Polymerase Extension Cloning (CPEC) presents a highly efficient alternative.

CPEC uses a high-fidelity DNA polymerase to join the insert (e.g., the mutated antibody gene) and the linearized vector. The method relies on primers designed with overlapping sequences for the vector ends. During the PCR-based reaction, the polymerase extends these overlapping regions, seamlessly assembling a circular, replication-competent plasmid [33]. Studies have demonstrated that CPEC accelerates library generation and yields a greater number of functional variants compared to traditional methods, thereby better preserving the diversity created by epPCR [33].

Screening and Selection Platforms

Screening is often the rate-limiting step in directed evolution. The choice of platform depends on the desired antibody property and the required throughput.

Cell Surface Display: This is a powerful selection (not just screening) technology that physically links the genotype (the antibody gene) to the phenotype (the displayed antibody protein) [34]. Common systems include:

- Yeast Surface Display: A eukaryotic system that facilitates proper folding and post-translational modification of antibody fragments. It is compatible with fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) for high-throughput screening of binding affinity and specificity [32] [34].

- Phage Display: Antibody fragments are displayed on the surface of filamentous phage. Libraries are subjected to panning rounds against the target antigen to enrich for binders. Recent advances integrate next-generation sequencing (NGS) for deep analysis of library diversity and enrichment [34] [35].

- Mammalian Cell Display: Allows for the display of full-length IgG antibodies in a host system with the most relevant cellular machinery for complex proteins, enabling direct functional screening [34].

Microfluidic Screening: Technologies like droplet microfluidics enable the ultra-high-throughput screening of millions of variants by compartmentalizing individual cells and assays in picoliter droplets, dramatically accelerating the discovery process [34].