Negative Design Strategies in Drug Discovery: Targeting Competing States for Selective Therapeutics

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of negative design strategies in drug discovery, a paradigm focused on engineering molecules to avoid undesirable biological states or interactions.

Negative Design Strategies in Drug Discovery: Targeting Competing States for Selective Therapeutics

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of negative design strategies in drug discovery, a paradigm focused on engineering molecules to avoid undesirable biological states or interactions. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, it covers the foundational principles of designing for negative outcomes—such as avoiding off-target binding or designing biodegradable pharmaceuticals. The review details methodological applications like Click Chemistry and Targeted Protein Degradation, addresses troubleshooting for optimization, and evaluates validation through study designs and comparative analysis. By synthesizing these intents, the article serves as a strategic guide for enhancing drug specificity, safety, and efficacy through deliberate negative design.

What is Negative Design? Foundational Principles and the Case for 'Benign-by-Design'

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What is negative design in protein engineering? Negative design is a computational protein design strategy focused on destabilizing competing, non-native states—such as misfolded, aggregated, or unintended oligomeric structures—to ensure the stability and specificity of the desired native state [1]. It is often used in conjunction with positive design, which stabilizes the target conformation [2] [1].

Why is negative design critical for creating reconfigurable protein assemblies? For multi-protein complexes that need to dynamically assemble and disassemble, individual subunits must be stable, soluble, and monomeric in isolation. Negative design is crucial to implicitly disfavor self-association of these subunits, which would otherwise prevent the desired reversible hetero-assembly [3]. This enables the construction of asymmetric systems that can undergo subunit exchange, mimicking dynamic biological processes [3].

What is the difference between explicit and implicit negative design?

- Explicit negative design involves computationally modeling specific, known off-target states and designing sequences that are energetically unfavorable for those states [3].

- Implicit negative design introduces structural and physicochemical features into the protein itself that broadly make a whole class of undesired states unlikely, without needing to model them all. This is achieved by creating well-folded protomers with polar or steric features that are incompatible with off-target interactions [3].

My designed protein is stable but forms homodimers instead of the intended heterodimer. What went wrong? This is a classic failure mode indicating insufficient negative design against self-association. Your design process likely over-stabilized the target heterodimeric interface with overly hydrophobic residues without incorporating features to disfavor the homodimeric state. Re-evaluate your interface design to include polar networks [3] and consider rigidly fusing structural elements to sterically block homodimer formation [3].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: High Background Aggregation in Individually Expressed Protomers

Description: When expressed and purified in isolation, one or more protein subunits form soluble aggregates or precipitate, indicating low stability or self-association.

| Potential Cause & Explanation | Solution |

|---|---|

| Marginal Native Stability: The protomer's folded state is not sufficiently lower in energy than unfolded states [2]. | Use evolution-guided atomistic design to improve stability. Filter mutation choices using natural sequence diversity, then perform atomistic calculations to stabilize the desired fold [2]. |

| Exposed Hydrophobic Patches: Surfaces designed for hetero-assembly are too hydrophobic, driving non-specific aggregation [3]. | Optimize interface composition. During sequence design, constrain the algorithm to favor polar residues at the interface while penalizing buried unsatisfied polar groups [3]. |

| Lack of Negative Design: The design process failed to disfavor the myriad of misfolded or aggregated states [2]. | Implement implicit negative design. Select starting scaffolds that are well-folded with substantial hydrophobic cores. Incorporate polar backbone atoms (e.g., from exposed beta strands) that are energetically costly to bury in incorrect states [3]. |

Problem: Slow or Irreversible Heterodimer Assembly

Description: Upon mixing, the designed protein components either fail to bind or bind very slowly, forming complexes that do not readily dissociate.

| Potential Cause & Explanation | Solution |

|---|---|

| Over-Stabilized Interface: The heterodimer interface is too rigid or hydrophobic, resembling a static complex rather than a dynamic one [3]. | Re-design for balanced affinity. Aim for micromolar to nanomolar affinity. Introduce explicit hydrogen bond networks and reduce non-specific hydrophobic burial to allow for faster on/off rates [3]. |

| Protomer Instability: Individual subunits are not stable monomers, leading to kinetic traps where they form non-productive aggregates before finding their correct partner [3]. | Ensure protomers are well-behaved monomers. Characterize individual subunits using SEC and native MS. Select designs where protomers are soluble and monodisperse across a range of concentrations [3]. |

Experimental Protocols & Data

Methodology for Designing and Testing Reconfigurable Heterodimers

The following workflow is adapted from a successful study on designing reconfigurable asymmetric protein assemblies [3].

- Scaffold Selection: Choose stable, monomeric protein scaffolds with mixed alpha-beta topology and an exposed beta-strand available for extension.

- Interface Design:

- Generate heterodimeric interfaces by structurally pairing the exposed beta-strand of one scaffold with a designed partner strand to form a continuous beta-sheet.

- Optimize side-chain interactions at the interface using Rosetta combinatorial sequence design, favoring polar residues and explicit H-bond networks to avoid excessive hydrophobicity [3].

- Implicit Negative Design:

- Model and disfavor potential homodimeric states by rigidly fusing designed helical repeat proteins (DHRs) to terminal helices to create steric clashes [3].

- Experimental Characterization:

- Co-expression & Affinity Purification: Co-express protomers in E. coli using a bicistronic vector with a His-tag on one partner. Assess complex formation via nickel affinity pulldown [3].

- Size Exclusion Chromatography (SEC): Analyze the complex and individual protomers for monodispersity and correct stoichiometry [3].

- Native Mass Spectrometry: Confirm the mass and composition of the assembled heterodimer [3].

- Binding Kinetics (BLI): Use Bio-Layer Interferometry to immobilize one biotinylated protomer and measure the association and dissociation rates of its partner. Successful dynamic designs exhibit rapid equilibration [3].

Quantitative Analysis of Designed Heterodimers (LHDs)

The table below summarizes key experimental data for a selection of successfully designed heterodimers (LHDs) [3].

| Design Name | Structural Class | Key Interface Feature | Affinity (Kd) | Association Rate (kon, M-1s-1) | Protomer Behavior in Isolation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LHD101 | Class 2 (helices on same side) | Continuous beta-sheet, polar networks | Micromolar to Nanomolar | ~106 | Monomeric at high concentration (>100 µM) |

| LHD29 | Class 1 (helices on opposite sides) | Continuous beta-sheet, polar networks | Low Nanomolar | ~102 | Monomeric after interface redesign (LHD274) |

| LHD275 | Class 3 (helices flank both sides) | Continuous beta-sheet, polar networks | Nanomolar | ~105 | Predominantly monomeric |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Rosetta Software Suite | A computational protein design package used for combinatorial sequence design and optimizing protein-protein interfaces [3]. |

| Bicistronic Expression Vector | A plasmid enabling the simultaneous, coordinated expression of two protomer genes in E. coli, crucial for testing complex formation [3]. |

| Size Exclusion Chromatography (SEC) System | An analytical technique to assess the size, monodispersity, and oligomeric state of purified proteins and complexes [3]. |

| Native Mass Spectrometer | An instrument used to determine the mass of intact protein complexes under non-denaturing conditions, verifying assembly stoichiometry [3]. |

| Bio-Layer Interferometry (BLI) System | A label-free technology for measuring real-time binding kinetics (e.g., kon, koff, KD) between designed protein partners [3]. |

| Buergerinin B | Buergerinin B, MF:C9H14O5, MW:202.20 g/mol |

| Yuexiandajisu E | Yuexiandajisu E, MF:C20H30O5, MW:350.4 g/mol |

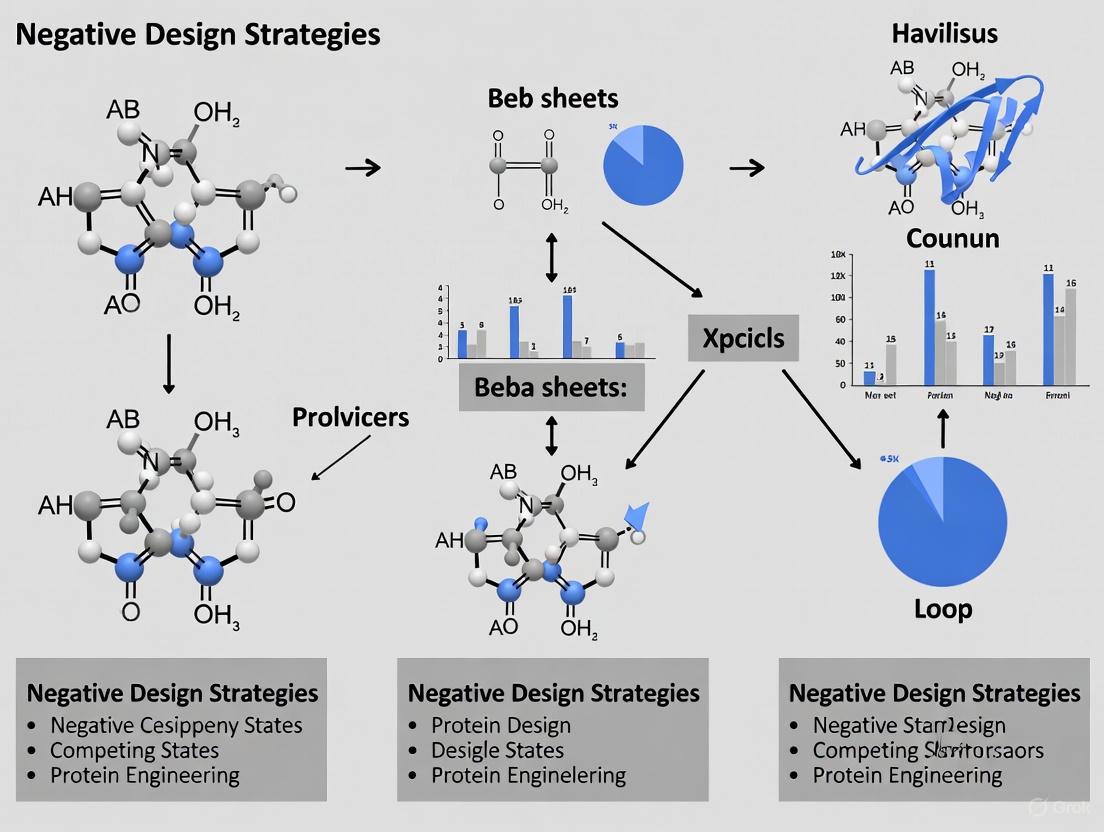

Visualization of Concepts and Workflows

Negative vs. Positive Design Strategy

Implicit Negative Design Workflow

Experimental Characterization Pipeline

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between positive and negative design in protein engineering? A1: Positive design is a strategy that focuses solely on maximizing the stability of a desired target structure or complex by introducing favorable interactions within it [4] [5]. Negative design, in conjunction with positive design, seeks to achieve specificity by explicitly modeling and destabilizing competing, unwanted states, making them energetically unfavorable [4] [5].

Q2: When is negative design considered critical for success? A2: Negative design is critical when the undesired structural states are very similar in configuration to the target state [4]. In such cases, mutations that stabilize the target are also likely to stabilize the competitors; explicit negative design is needed to break this correlation and achieve specificity [4].

Q3: What is a key trade-off between stability and specificity? A3: There is a documented trade-off where proteins designed with only positive design (stability-design) can be experimentally more stable, but may form heterogeneous mixtures (e.g., homodimers and heterodimers). Proteins designed with both positive and negative design (specificity-design) form homogenous, specific complexes (e.g., pure heterodimers) but can be less stable [4].

Q4: How does 'contact-frequency' influence the choice of design strategy? A4: Research on lattice models and real proteins shows that the balance between positive and negative design is determined by a protein's average contact-frequency—the fraction of a sequence's conformational ensemble in which any two residues are in contact [5]. Positive design is favored when the average contact-frequency is low, as stabilizing native interactions are rare in non-native states. Negative design is favored when the average contact-frequency is high, because the interactions that stabilize the native state are also common in competing non-native states, requiring explicit destabilization of the latter [5].

Q5: What is an experimental method to verify the success of a negative design? A5: Analytical ultracentrifugation can be used to monitor the populations of different assembled species (e.g., homodimers vs. heterodimers) in solution. The success of a specificity-design (positive and negative) is indicated by the formation of an almost exclusive heterodimer population, in contrast to a stability-design (positive only), which often forms a mixture [4].

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol 1: Computational Design of a Protein Heterodimer This protocol outlines the process for re-engineering a protein homodimer into a heterodimer, comparing stability-design (positive only) and specificity-design (positive and negative) strategies [4].

System Setup:

- Use the crystal structure of the wild-type homodimer (e.g., SspB, PDB: 1OU9).

- Select key interface positions for computational randomization (e.g., residues 12, 15, 16, 101).

- Define an allowed set of amino acids (e.g., Gly, Ala, Ser, Val, Thr, Leu, Ile, Phe, Tyr, Trp).

Energy Function Configuration:

- Use a molecular mechanics force field (e.g., Dreiding) to calculate energies.

- Include terms for van der Waals interactions (scaled), hydrophobic solvation, hydrogen bonding, and electrostatics.

Stability Design (Positive Design):

- Use a search algorithm like Dead-End Elimination (DEE) to find the sequence with the lowest calculated energy for the target heterodimer state.

Specificity Design (Positive and Negative Design):

- Modify the algorithm to optimize for specificity. Calculate an optimization energy:

E_opt = 2E_AB - E_AA - E_BB, where EAB is the heterodimer energy, and EAA/E_BB are the homodimer energies. - To account for structural relaxation in competing states, apply an energy ceiling on unfavorable van der Waals interactions in the homodimer states.

- Use a Monte Carlo search to find sequences that minimize

E_opt.

- Modify the algorithm to optimize for specificity. Calculate an optimization energy:

Experimental Validation:

- Protein Expression & Purification: Co-express designed subunits in E. coli and purify complexes using affinity and ion-exchange chromatography [4].

- Stability Assay: Perform urea denaturation experiments monitored by tryptophan fluorescence to determine the free energy of unfolding (ΔG) and midpoint of denaturation (Cm) [4].

- Specificity Assay: Use analytical ultracentrifugation to determine the molecular weight and homogeneity of the assembled species in solution [4].

Protocol 2: Urea Denaturation to Measure Protein Stability This method assesses the thermodynamic stability of a designed protein complex [4].

- Sample Preparation: Incubate the protein (e.g., at 1.5 μM dimer concentration) in a series of buffers with varying concentrations of urea (e.g., 0-8 M) for at least 1 hour to reach equilibrium.

- Signal Monitoring: Use a spectrofluorometer to track changes in intrinsic tryptophan fluorescence as the protein unfolds.

- Data Analysis: Fit the data to a model that describes a transition from a folded dimer to unfolded monomers, extracting the free energy of unfolding (ΔG) and the Cm.

Data Presentation

Table 1: Comparison of Stability-Design vs. Specificity-Design Strategies

| Feature | Stability-Design (Positive Only) | Specificity-Design (Positive & Negative) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Objective | Maximize stability of the target complex [4] | Achieve specificity for the target over competing states [4] |

| Computational Strategy | Minimize energy of target state (E_AB) [4] | Minimize optimization energy (2EAB - EAA - E_BB) [4] |

| Theoretical Trade-off | High native-state stability [5] | Specificity when contact-frequency is high [5] |

| Experimental Outcome: Stability | Higher stability (lower free energy, higher Cm in denaturation) [4] | Lower stability relative to stability-design [4] |

| Experimental Outcome: Specificity | Forms mixture of species (e.g., homodimers and heterodimers) [4] | Forms homogeneous target complex (e.g., pure heterodimer) [4] |

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| SspB Adaptor Protein (structured domain) | The model system for re-engineering protein-protein interactions; forms a wild-type homodimer that can be computationally redesigned into a heterodimer [4]. |

| ClpXP Protease | In the broader SspB system, this protease is the biological target to which SspB delivers substrates; used for functional activity assays of designed variants [4]. |

| Ni++-NTA Resin | For affinity chromatography purification of His-tagged protein constructs [4]. |

| MonoQ Column | Anion-exchange chromatography resin for further purification of protein complexes and separating heterodimers from homodimers [4]. |

| Urea | Chemical denaturant used in equilibrium unfolding experiments to determine protein stability [4]. |

Mandatory Visualization

Diagram 1: Positive vs Negative Design Concept

Diagram 2: Specificity Design Energy Optimization

Diagram 3: Experimental Workflow for Validation

FAQs and Troubleshooting Guides

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What is the core objective of the Benign-by-Design (BbD) concept in medicinal chemistry? The core objective is to design Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients (APIs) so that they maintain efficacy during storage and use but degrade at a reasonable rate after excretion and release into the environment. This aims to prevent their accumulation as micro-pollutants in water and soil, thereby reducing ecological harm [6] [7]. It shifts the focus from "end-of-pipe" pollution treatments to a proactive "beginning-of-the-pipe" design philosophy [7].

Q2: How does BbD align with the principles of Green Chemistry? BbD directly implements the 10th principle of Green Chemistry, "design for degradation." It calls for chemical products to be designed in such a way that they break down into innocuous substances after their function is complete, thus preserving the efficacy of the drug while enhancing its environmental biodegradability [6] [7] [8].

Q3: Is it feasible to design a drug that is both stable for therapy and degradable in the environment? Yes, feasibility is demonstrated by existing examples. The strategy exploits the different physical-chemical conditions at various life cycle stages (e.g., stable at pH and temperature of storage, but degradable at the pH, redox potential, or microbial conditions found in sewage treatment or surface water) [7]. Drugs like cytarabine and the research candidate glufosphamide (a glucose-modified ifosfamide) show that incorporating certain functional groups can enhance biodegradability without compromising therapeutic action [7].

Q4: What is a major challenge in designing biodegradable APIs? A primary challenge is the inherent conflict between the need for sufficient chemical stability to ensure a reasonable shelf-life and desired in vivo pharmacokinetics, and the simultaneous requirement for ready degradability in the environment. The precise chemical structure dictates biological activity, making alterations for degradability non-trivial [6].

Q5: How does the "negative design" concept relate to BbD? Within the context of molecular design, "negative design" involves strategically disfavoring unwanted states or properties. In BbD, this means designing an API's molecular structure to not only favor the desired therapeutic activity (positive design) but also to actively disfavor environmental persistence—making it an unlikely candidate for a long-lived, stable pollutant in aquatic or terrestrial systems [2] [7].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental & Design Challenges

Problem: Designed API derivative shows inadequate biodegradability in screening assays.

- Potential Cause 1: The introduced labile group is too stable under environmental conditions.

- Solution: Explore a wider range of hydrolyzable groups (e.g., esters, amides) or functional groups susceptible to microbial attack. Consider the specific conditions of enzymatic systems in wastewater treatment plants [7].

- Potential Cause 2: The molecular scaffold itself is highly recalcitrant.

- Solution: Use non-targeted synthesis and screening to generate a broader library of derivatives. This can help identify unexpected structure-biodegradability relationships that a purely rational design might miss [7].

Problem: API derivative loses significant pharmacological activity.

- Potential Cause: The molecular modification for degradability interfered with the pharmacophore or critical target-binding interactions.

- Solution: Focus on introducing biodegradable "soft" spots in peripheral regions of the molecule, away from the core pharmacophore. Techniques like molecular modeling and structural bioinformatics can help predict the impact of modifications on target binding [7].

Problem: High levels of toxic Transformation Products (TPs) are generated upon degradation.

- Potential Cause: The degradation pathway of the parent API leads to the formation of stable, harmful intermediates.

- Solution: Conduct thorough transformation product analysis during the design phase. Aim for molecular architectures that ultimately lead to full mineralization or the formation of benign end products. Avoid motifs known to generate toxic TPs [7].

Experimental Protocols & Data

Protocol 1: High-Throughput Biodegradability Screening for API Derivatives

Objective: To rapidly assess the inherent biodegradability of novel API derivatives under standardized conditions simulating a sewage treatment plant.

Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare aqueous solutions of the candidate API and a control (e.g., known biodegradable and non-biodegradable compounds) at environmentally relevant concentrations (e.g., µg/L to mg/L).

- Inoculation: Inoculate the solutions with a defined concentration of activated sludge from a municipal wastewater treatment plant to introduce a diverse microbial community.

- Incubation: Incubate the sealed vessels in the dark at a controlled temperature (e.g., 20-25°C) to simulate ambient conditions. Maintain abiotic controls (e.g., sterilized sludge) to account for chemical hydrolysis.

- Monitoring: Monitor the disappearance of the parent compound over time (e.g., 28-day period) using analytical techniques like Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS).

- Analysis: Calculate the percentage of biodegradation based on the removal of the parent compound. Screen for the formation and subsequent degradation of major transformation products [7].

Protocol 2: Functional Group Modification for Enhanced Hydrolysis

Objective: To systematically introduce ester linkages into a lead compound and evaluate the impact on both chemical stability (shelf-life) and environmental hydrolysis.

Methodology:

- Retrosynthetic Analysis: Identify non-critical hydroxyl or carboxyl groups in the lead molecule that can be chemically derivatized to form ester bonds.

- Synthetic Chemistry: Synthesize a small library of ester-based analogs.

- Stability Testing:

- Forced Degradation: Subject analogs to accelerated stability conditions (e.g., elevated temperature and humidity) according to ICH guidelines to predict shelf-life.

- Hydrolytic Studies: Incubate analogs in buffers at different pH levels (e.g., 2, 7, 9) and in environmental water samples to measure hydrolysis rates.

- Bioactivity Assay: Test all stable analogs in relevant pharmacological assays to ensure therapeutic efficacy is retained [7].

Data Presentation

Table 1: Impact of Specific Functional Groups on API Biodegradability and Activity

Table summarizing examples of molecular modifications and their outcomes.

| API / Lead Compound | Molecular Modification | Effect on Biodegradability | Effect on Pharmacological Activity | Key Reference / Example |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ifosfamide | Addition of a glucose moiety (forming Glufosphamide) | Significantly increased | Retained and potentially improved (reached late-stage clinical trials) | [7] |

| 5-Fluorouracil | N/A (parent compound) | Not readily biodegradable | Cytotoxic activity | [7] |

| Cytarabine | Contains a (non-fluorinated) sugar moiety | Readily biodegradable | Retained (in clinical use for decades) | [7] |

| Gemcitabine | Contains a fluorinated sugar moiety | Lower biodegradability than Cytarabine | Retained (in clinical use for decades) | [7] |

| Praziquantel | Use of pure (R)-enantiomer (Arpraziquantel) | (Focus was on reduced side effects & dose) | Retained anthelmintic efficacy; improved taste/safety profile | [9] |

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for BbD Experiments

Essential materials and their functions in Benign-by-Design research.

| Reagent / Material | Function in BbD Research | Specific Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Activated Sludge Inoculum | Provides a diverse microbial community for biodegradability screening assays. | Simulating the biological degradation environment of a municipal wastewater treatment plant in OECD standard tests [7]. |

| LC-MS/MS Systems | Highly sensitive and selective identification and quantification of APIs and their transformation products (TPs). | Monitoring the degradation kinetics of a parent API and identifying the structures of potentially persistent TPs [7]. |

| Defined Hydrolytic Buffers | To study the chemical (abiotic) degradation profile of an API under different pH conditions. | Assessing the hydrolysis rate of an ester-containing API analog at pH 2 (stomach) vs. pH 8 (environmental) [7]. |

| "Soft Spot" Prediction Software | Computational tools to predict sites on a molecule that are metabolically labile or amenable to modification. | Guiding the rational design of biodegradable groups into a molecule without disrupting the pharmacophore. |

Workflow and Pathway Diagrams

BbD Molecular Design Workflow

API Life Cycle & BbD Intervention

A central challenge in modern drug delivery is mastering the competition between two critical, often opposing, states: architectural stability and controlled biodegradation. This is not a problem to be solved by choosing one over the other, but a design parameter that must be precisely tuned. From the perspective of negative design strategies—where we define what the system must not be or do—the objective is clear: the drug architecture must not be so stable that it fails to release its therapeutic payload or causes long-term toxicity, nor must it be so fragile that it degrades prematurely before reaching its target.

This competition is framed by two fundamental requirements:

- Maintain structural integrity from administration until the target site is reached.

- Initiate predictable and complete biodegradation upon reaching the target site, leading to timely drug release and clearance of the carrier materials.

The following guide provides troubleshooting and methodological support for researchers navigating this critical design challenge.

FAQs on Stable vs. Biodegradable Architectures

Q1: What are the primary factors that control the degradation rate of a biodegradable polymer, and how can I adjust them?

The degradation rate is a function of the polymer's intrinsic properties and its environment. Key factors and their effects are summarized in the table below [10] [11].

Table 1: Key Factors Influencing Polymer Degradation Rate

| Factor | Impact on Degradation Rate | Design Adjustment Strategy |

|---|---|---|

| Chemical Structure/Composition | Determines the lability of chemical bonds. Anhydrides > Esters > Amides [11]. | Select monomers with more hydrolytically labile bonds (e.g., anhydrides) for faster degradation. |

| Crystallinity | Higher crystallinity leads to slower degradation, as the crystalline regions are more resistant to hydrolysis [11]. | Manipulate processing conditions to control the degree of crystallinity in the final architecture. |

| Hydrophilicity | More hydrophobic polymers degrade more slowly due to reduced water penetration [11]. | Incorporate hydrophilic co-monomers or additives to increase water uptake and accelerate degradation. |

| Molecular Weight | Higher molecular weight generally correlates with a slower degradation rate [10]. | Vary polymerization conditions to control the initial molecular weight and its distribution. |

| Morphology (Porosity, Surface Area) | Higher porosity and surface area increase contact with aqueous media, accelerating degradation [10]. | Use fabrication techniques (e.g., porogen leaching) that create more open or porous matrix structures. |

Q2: How can I prevent my nanoparticle formulation from aggregating before it has a chance to act?

Aggregation is a failure of colloidal stability, often stemming from high surface energy. To prevent this:

- Use Stabilizing Excipients: Incorporate surfactants (e.g., polysorbates) or steric stabilizers (e.g., polyethylene glycol, PEG) during formulation. These molecules adsorb to the nanoparticle surface and create a repulsive barrier, preventing aggregation [12].

- Optimize Lyophilization: If freeze-drying is required for storage, use appropriate cryoprotectants (e.g., sucrose, trehalose) to protect the nanoparticle structure from ice-induced stresses and prevent aggregation upon reconstitution [12].

- Control Environmental Conditions: Store formulations at a pH and ionic strength that maximize electrostatic repulsion between particles, and avoid temperature extremes.

Q3: What does a "biphasic" release profile indicate about my system's stability and degradation?

A biphasic release profile—characterized by a large initial "burst" of drug followed by a slower, sustained release—is a classic sign of a stability-degradation mismatch. This often indicates:

- Poor Encapsulation Stability: The burst release suggests that a significant fraction of the drug is weakly associated with or adsorbed to the surface of the delivery system, rather than being stably encapsulated within the matrix [13].

- Surface-Localized Drug: The initial burst is from drug molecules on or near the surface that dissolve rapidly.

- Degradation-Controlled Second Phase: The subsequent sustained release is governed by the slower process of polymer hydrolysis or enzymatic degradation, which frees the entrapped drug from the core of the system. To mitigate burst release, optimize encapsulation efficiency and drug-polymer interactions to ensure the drug is homogeneously dispersed within the polymer matrix [11].

Q4: My protein therapeutic is losing activity in the biodegradable polymer matrix. How can I stabilize it?

Proteins are particularly susceptible to destabilization during encapsulation and release. This is a critical failure where the carrier's chemical environment negatively impacts the drug.

- Formulate with Stabilizing Excipients: Add stabilizers like sugars (sucrose, trehalose), amino acids (histidine, glycine), or surfactants to the internal aqueous phase during encapsulation. These can protect the protein from interfacial stresses, dehydration, and interaction with the polymer [12].

- Modify the Polymer Chemistry: If the polymer or its degradation products create an acidic microclimate (a known issue with PLGA), consider incorporating basic salts (e.g., Mg(OH)â‚‚) into the formulation to neutralize the pH [12].

- Employ a "Quality by Design" (QbD) Framework: Use Analytical Quality by Design (AQbD) principles to understand how variations in raw materials and process parameters impact the critical quality attribute of protein stability, allowing for proactive control [14].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Challenges

Table 2: Troubleshooting Common Formulation and Processing Defects

| Problem | Possible Reason (Negative Design Principle Violated) | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Rapid, Incomplete Drug Release | The system is too stable; polymer degradation is minimal, and release relies solely on diffusion, which is insufficient. | Reformulate to increase biodegradability: use a polymer with a lower molecular weight or more hydrophilic character [13] [11]. |

| Premature Drug Release (Burst Effect) | The system is not stable enough initially; drug is poorly encapsulated or adsorbed to the surface. | Improve encapsulation efficiency; use a more hydrophobic polymer or a higher molecular weight polymer to slow water ingress; apply a rate-controlling coating [11]. |

| Protein Aggregation/Inactivation | The internal microenvironment is not stable for the biologic; stresses from fabrication, polymer acidity, or hydration cause denaturation. | Incorporate protein-stabilizing excipients (e.g., sugars) and consider using a polymer that generates a more neutral pH upon degradation [12]. |

| High Toxicity or Immune Response | The system is too stable or degrades into toxic by-products; carrier accumulates or releases irritating monomers. | Switch to a polymer with a proven safety profile (e.g., PLGA, chitosan); ensure degradation products are biocompatible and readily cleared [10]. |

| Tablet Capping/Lamination | The mechanical stability of the tablet is compromised; too many fine particles, entrapped air, or incorrect compression force. | Use efficient binding agents, adjust lubricant, employ pre-compression, and reduce press speed to allow air to escape [15]. |

| Tablet Sticking | The formulation is chemically or physically adhesive to the metal punch faces. | Ensure the granulate is completely dried; use an efficient lubricant (e.g., magnesium stearate); polish punch faces [15]. |

Experimental Protocols for Characterizing Stability and Biodegradation

Protocol 1: In Vitro Drug Release and Polymer Erosion

This is the fundamental experiment for quantifying the competition between drug release and carrier degradation.

1. Objective: To simultaneously measure the kinetics of drug release from a polymeric matrix and the mass loss of the polymer itself, providing a direct correlation between stability and biodegradation.

2. Materials:

- Test Samples: Pre-weighed drug-loaded polymeric films, microparticles, or nanoparticles.

- Release Medium: Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) at physiological pH (7.4) or other biorelevant media (e.g., simulated gastric/intestinal fluid).

- Equipment: Shaking water bath or dissolution apparatus, centrifuge, HPLC system for drug quantification, freeze dryer, analytical balance.

3. Methodology:

- Step 1: Precisely weigh the sample (Wâ‚€).

- Step 2: Immerse the sample in a controlled volume of release medium under sink conditions. Maintain at 37°C with constant agitation.

- Step 3: At predetermined time points, centrifuge the medium (if using particles) to separate the released drug from the undegraded polymer.

- Step 4: Analyze the supernatant for drug concentration using HPLC or another validated analytical method. Replace the release medium to maintain sink conditions.

- Step 5: At key time points (e.g., after burst release, during sustained release), remove a set of samples from the medium, rinse with water, freeze-dry, and weigh (Wₜ).

- Step 6: Calculate cumulative drug release and polymer mass loss over time.

4. Data Analysis:

- Drug Release: % Cumulative Release = (Amount of drug released at time t / Total drug loaded) × 100.

- Polymer Erosion: % Mass Loss = [(W₀ - Wₜ) / W₀] × 100.

- Interpretation: Plot both curves on the same graph. An ideal system will show a close correlation between polymer erosion and drug release, indicating a degradation-controlled mechanism. A significant lag between mass loss and drug release suggests a diffusion-dominated system that may be too stable.

Protocol 2: Evaluating Storage Stability of Biologics-Loaded Formulations

This protocol assesses the system's ability to maintain its structure and the activity of a labile drug during storage.

1. Objective: To determine the shelf-life of a biodegradable drug delivery system containing a biologic (e.g., a protein or peptide) by monitoring physical and chemical stability under accelerated conditions.

2. Materials:

- Test Samples: Lyophilized or liquid formulations of biologic-loaded nanoparticles/microparticles.

- Stability Chambers: For controlled temperature and humidity.

- Analytical Tools: Size and Zeta Potential Analyzer, SDS-PAGE or SEC-HPLC, bioactivity assay.

3. Methodology:

- Step 1: Store sealed samples at accelerated conditions (e.g., 25°C/60% RH, 40°C/75% RH) and recommended long-term conditions (2-8°C or -20°C).

- Step 2: At time points (e.g., 0, 1, 3, 6 months), withdraw samples for analysis.

- Step 3:

- Physical Stability: Rehydrate/reconstitute samples and measure particle size, polydispersity index (PDI), and zeta potential. Aggregation or size change indicates physical instability.

- Chemical Stability: Analyze for degradation products (e.g., by SDS-PAGE for protein aggregates or fragments, SEC-HPLC for purity).

- Bioactivity: Perform a cell-based or enzymatic assay to confirm the biologic has retained its therapeutic activity.

4. Data Analysis: Track changes in each parameter over time. Use data from accelerated conditions to predict shelf-life at recommended storage temperatures. A stable formulation will show minimal change in size, zeta potential, chemical purity, and bioactivity.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Biodegradable Drug Delivery Systems

| Item | Function in Research | Relevance to Stability/Biodegradation |

|---|---|---|

| PLGA (Poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid)) | A synthetic, tunable copolymer and the gold standard for biodegradable drug delivery. | The lactide:glycolide ratio and molecular weight allow precise control over degradation rate and mechanical stability [13] [10]. |

| Chitosan | A natural, cationic polysaccharide derived from chitin. | Offers mucoadhesive properties and degrades via enzymatic hydrolysis; its degradation rate is influenced by the degree of deacetylation [10]. |

| PEG (Polyethylene Glycol) | A synthetic polymer used for "stealth" coating. | Improves colloidal stability and extends circulation half-life by reducing opsonization and aggregation (enhances stability) [13] [12]. |

| Lysozyme | An enzyme that degrades certain natural polymers. | Used in in vitro studies to simulate enzymatic biodegradation of polymers like chitosan, providing a more biologically relevant degradation profile [10]. |

| Trehalose / Sucrose | Disaccharide sugars used as stabilizers. | Protect proteins and nanoparticles during freeze-drying and storage by acting as cryoprotectants and lyoprotectants, preventing aggregation and inactivation (enhances stability) [12]. |

| Cellulose Derivatives (e.g., HPMC) | Semisynthetic polymers used as viscosity enhancers and matrix formers. | Provide controlled drug release through swelling and gel formation; their hydrophilicity and viscosity grade influence release kinetics and stability [10]. |

| Lancifodilactone C | Lancifodilactone C, MF:C29H36O10, MW:544.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| AB8939 | AB8939, CAS:1974336-09-8, MF:C22H24N4O3, MW:392.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Visualizing the Workflow and Design Logic

Diagram 1: Stability vs. Biodegradation Design Workflow

This diagram outlines the iterative process of designing and optimizing a drug delivery system to balance stability and biodegradation.

Diagram 2: Competitive States Design Logic

This diagram illustrates the core "competing states" logic that underpins negative design strategies for these systems, showing the ideal zone and the failure modes to be avoided.

Exploring the 'Competing States' Problem in Target Engagement

Technical Support Center

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why is confirming target engagement in a live cellular environment so critical, and why can't I rely solely on in vitro biochemical data?

A1: Measurements of target engagement in living systems are essential because the cellular environment can dramatically alter how a chemical probe interacts with its intended target. Factors such as cell permeability, active transport, intracellular metabolism of the probe, and local target concentration can differ significantly from in vitro conditions [16].

Research has shown that some inhibitors demonstrate dramatic differences in their activity against native kinases in cells versus recombinant kinases in vitro [16]. This means that a potent inhibitor in a test tube might fail to engage its target in a complex cellular milieu. Furthermore, proteins can exist in multiple conformational states in cells, and a probe might only be able to engage a specific, functionally relevant state that is regulated by dynamic processes like protein phosphorylation [16]. Relying only on in vitro data risks attributing a compound's pharmacological effects to the wrong mechanism.

Q2: My chemical probe is designed to bind reversibly. What methods can I use to reliably measure its engagement with the target protein in situ?

A2: For reversible binders, you can use chemoproteomic methods that incorporate photoreactive groups and bioorthogonal handles. The general workflow involves:

- Creating a Photoreactive Analogue: Design a version of your chemical probe that contains both a latent affinity handle (like an alkyne or azide) and a photoreactive group (e.g., a diazirine) [16].

- In Situ Treatment and Crosslinking: Treat living cells with this analogue. Then, expose the cells to UV light. This light activates the photoreactive group, triggering a covalent bond between the probe analogue and its protein target(s), effectively "trapping" the interaction [16].

- Target Detection and Identification: After cell lysis, use a bioorthogonal reaction, such as copper-catalyzed azide-alkyne cycloaddition (CuAAC), to attach a reporter tag (e.g., biotin or a fluorophore) to the affinity handle [16]. The labeled proteins can then be enriched and identified using avidin pulldown followed by mass spectrometry.

This approach allows for the direct mapping of on-target and off-target interactions directly in living cells, providing a more accurate picture of a reversible probe's behavior [16].

Q3: I've confirmed target engagement, but my compound still doesn't produce the expected phenotypic effect. What could be going wrong?

A3: This situation highlights a key reason for measuring target engagement. If you have robust evidence of full target occupancy in vivo but observe no therapeutic effect, it strongly suggests that the target itself was properly tested but invalidated for the intended clinical indication [16]. In other words, modulating this specific target is not sufficient to produce the desired phenotypic outcome.

However, before concluding target invalidation, consider these other potential issues that could create a "competing state" and mask the expected effect:

- Off-target Activity: Your probe might be engaging unintended proteins, and their effects could be counteracting the on-target effect. Using broad-spectrum competitive ABPP or kinobeads can help identify these off-targets [16].

- Signal Transduction Redundancy: The cellular network might compensate for the inhibition of your target through parallel signaling pathways, a phenomenon known as pathway redundancy.

- Feedback Loops: The inhibition might trigger a compensatory feedback mechanism that reactivates the pathway downstream of your target.

Q4: What are the best practices for assessing the selectivity of my chemical probe across a wide range of potential off-targets?

A4: Broad-spectrum, competitive chemoproteomic platforms are considered best practice for assessing selectivity in a cellular context. Two established methods are:

- Kinobeads: Incubate proteomes from probe-treated and vehicle-treated cells with bead-immobilized, broad-spectrum kinase inhibitors. The bound kinases are then analyzed and quantified by LC-MS. Kinases that show reduced binding in the probe-treated sample are considered engaged by the probe [16].

- Competitive Activity-Based Protein Profiling (ABPP): This method uses broad-spectrum activity-based probes to monitor the activity of entire enzyme families in native proteomes. You pre-treat cells with your chemical probe or vehicle, then lysate the cells and treat the proteomes with the activity-based probe. Proteins that are engaged by your chemical probe will show reduced labeling by the activity-based probe, which can be quantified by LC-MS [16].

These parallel methods allow you to evaluate your probe against hundreds of proteins simultaneously, revealing unanticipated off-targets and network-wide effects [16].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Measuring Cellular Target Engagement using Competitive ABPP

This protocol is ideal for assessing engagement of enzymes that can be profiled with activity-based probes.

1. Materials:

- Cells expressing your target of interest.

- Your chemical probe and a vehicle control (e.g., DMSO).

- Appropriate activity-based probe (ABP) for your enzyme class.

- Lysis buffer.

- Reagents for copper-click chemistry (if using a "clickable" ABP): Copper sulfate, Tris[(1-benzyl-1H-1,2,3-triazol-4-yl)methyl]amine (TBTA), and a fluorescent azide (e.g., TAMRA-azide) or biotin-azide.

- SDS-PAGE gel or LC-MS instrumentation.

2. Methodology:

- Step 1: Cell Treatment. Divide cells into two groups. Treat one group with your chemical probe at the desired concentration. Treat the control group with vehicle only. Incubate under normal culture conditions to allow for target engagement (typically 1-6 hours).

- Step 2: Cell Lysis. Wash and lyse the cells to generate native proteomes.

- Step 3: ABP Labeling. Incubate the proteomes from both groups with the activity-based probe. The ABP will covalently label the active sites of its enzyme targets.

- Step 4: Detection.

- For gel-based analysis: If the ABP is fluorescent, directly visualize by in-gel fluorescence scanning. If it is "clickable," perform a copper-click reaction with a fluorescent azide tag, then visualize.

- For MS-based analysis: If a "clickable" ABP with a biotin tag is used, perform the click reaction, enrich biotinylated proteins with streptavidin beads, trypsinize, and analyze by LC-MS/MS.

- Step 5: Data Analysis. Compare the ABP labeling signal between the probe-treated and vehicle-treated samples. A specific reduction in the labeling intensity of your target protein indicates successful engagement by your chemical probe in the cellular context [16].

Protocol 2: Assessing Kinase Engagement using the Kinobeads Platform

This protocol outlines the general workflow for a kinobeads pull-down experiment.

1. Materials:

- Kinobeads (commercially available or prepared in-house).

- Cell lines or tissues of interest.

- Your kinase inhibitor (chemical probe) and vehicle control.

- Lysis buffer (compatible with kinobeads binding).

- Equipment for affinity purification and LC-MS/MS.

2. Methodology:

- Step 1: Preparation of Soluble Proteomes. Lyse cells or tissue that have been treated with your inhibitor or vehicle control. Clarify the lysate by centrifugation to obtain the soluble proteome.

- Step 2: Affinity Purification. Incubate the soluble proteomes with kinobeads. The beads will capture a large proportion of the kinome from the sample.

- Step 3: Washing and Elution. Wash the beads thoroughly to remove non-specifically bound proteins. Elute the bound kinases.

- Step 4: Proteomic Analysis. Digest the eluted proteins with trypsin and analyze the resulting peptides by quantitative LC-MS/MS (e.g., using TMT or label-free quantification).

- Step 5: Data Analysis. Identify and quantify the kinases captured by the kinobeads. Kinases that show a significant reduction in abundance in the inhibitor-treated sample compared to the vehicle control are considered engaged by your chemical probe [16].

The table below summarizes key characteristics of major target engagement methodologies.

| Method | Key Readout | Throughput | Applicability | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Substrate-Product Assay [16] | Changes in substrate/product levels | Medium | Enzymes with defined, unique activities | Direct functional readout |

| Competitive ABPP [16] | Reduction in ABP labeling signal | High | Enzymes with active-site probes | Direct measurement in native systems; maps off-targets |

| Kinobeads / Chemoproteomics [16] | Reduction in target binding to immobilized beads | High | Kinases & other druggable families | Broad profiling of on-target and off-target engagement |

| Photocrosslinking & Pulldown [16] | Covalent capture of target-probe complex | Low | Reversible binders (with probe design) | Confirms direct binding in living cells |

Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists essential materials and tools for conducting robust target engagement studies.

| Research Reagent | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| Activity-Based Probes (ABPs) [16] | Broad-spectrum or tailored chemical reagents that covalently label the active site of enzymes in native proteomes. They are the core component for competitive ABPP assays. |

| "Clickable" Probes (with alkynes/azides) [16] | Chemical probes incorporating bioorthogonal handles. They allow for minimal steric perturbation during experiments and enable highly sensitive downstream detection via click chemistry. |

| Photoreactive Groups (e.g., Diazirines) [16] | Chemical moieties that form covalent bonds with nearby proteins upon UV light exposure. They are used to create analogue probes for trapping interactions with reversible binders. |

| Immobilized Broad-Spectrum Inhibitors (Kinobeads) [16] | Beads coated with a mixture of non-selective kinase inhibitors. They are used to affinity-capture a large portion of the kinome from native proteomes for competitive binding studies. |

| Cellular Thermal Shift Assay (CETSA) | A method (not in search results but widely used) that measures protein stabilization upon ligand binding by applying a thermal challenge to intact cells or lysates. |

Experimental Workflow and Pathway Diagrams

Diagram 1: The critical path for target validation demonstrates how confirming target engagement resolves ambiguity when a probe lacks efficacy [16].

Diagram 2: The competing states problem shows a protein existing in equilibrium between a probe-accessible state and an inaccessible state [16].

Methodologies for Negative Design: From Click Chemistry to Targeted Degradation

Click Chemistry as a Tool for Modular and Specific Molecular Assembly

Click chemistry describes a suite of powerful, highly reliable, and selective reactions for the rapid synthesis of useful new compounds and complex architectures from modular building blocks [17]. This approach emphasizes the formation of carbon-heteroatom bonds using "spring-loaded" reactants that operate under operationally simple, water-tolerant conditions, are largely unaffected by pH or temperature, and generate products in high yields with minimal purification requirements [17]. The paradigm has revolutionized strategies for molecular assembly, particularly in drug discovery and chemical biology, by providing connections that are both highly specific and broadly applicable.

Within the conceptual framework of negative design strategies and competing states research, click chemistry offers a powerful means to enforce pathway specificity. By employing reactions that are highly favored both thermodynamically and kinetically, researchers can effectively eliminate undesirable side reactions and competing molecular states that might otherwise lead to failed assemblies or non-functional constructs. This review establishes a technical support foundation for implementing these reactions effectively, addressing common experimental challenges through detailed troubleshooting guides, optimized protocols, and essential resource documentation.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) and Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ: Addressing Common Experimental Challenges

Q1: What are the primary limitations of click chemistry in biological systems?

| Limitation | Impact | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Copper Cytotoxicity [18] | Copper(I) catalysts essential for CuAAC can be toxic to living cells, causing interference and viability issues. | Utilize metal-free alternatives such as strain-promoted azide-alkyne cycloaddition (SPAAC) [19] or employ water-soluble copper ligands to enhance catalyst efficiency at lower, less toxic doses [19]. |

| Endogenous Interference [20] | Biological thiols (e.g., cysteine residues) can react with alkynes, leading to non-specific labeling and false positives. | Implement a pre-treatment step with a low concentration of hydrogen peroxide to shield against thiol interference before introducing click reagents [20]. |

| Reagent Stability [18] | Phosphine reagents used in Staudinger ligation are prone to air oxidation, degrading over time and reducing reaction efficiency. | Prepare phosphine stocks under inert atmosphere, store appropriately, and use fresh solutions. Consider alternative bioorthogonal reactions like inverse electron-demand Diels-Alder (IEDDA) [19]. |

| Unwanted Dimerization [18] | Alkynes can sometimes react with each other (homo-coupling) instead of with the intended azide partner. | Ensure both reactive groups (azide and alkyne) are positioned at the ends of alkyl chains to minimize steric hindrance and favor the intended cycloaddition [18]. |

Q2: How can I improve the specificity of target identification using clickable probes in living cells?

- Optimize Photo-affinity Groups: Avoid benzophenones due to weaker photo-crosslinking activity. Prefer diazirines as photo-affinity groups, but note their efficiency is highly dependent on wavelength, with optimal activation often at 365 nm [20].

- Mitigate Common Off-Targets: Cytoskeleton proteins (tubulin, actin) and stress proteins (e.g., HSP90) are frequently captured non-specifically. When these proteins appear in results, employ rigorous control experiments with photo-affinity probes lacking the drug guidance to confirm true targets [20].

- Validate with Orthogonal Methods: Do not rely solely on click chemistry results. Confirm target engagement and identity through complementary techniques like immunofluorescence co-localization or other biochemical assays [20].

Q3: What are the key considerations for building chemical libraries using click chemistry?

The SuFEx (Sulfur Fluoride Exchange) click chemistry platform, particularly using reagents like fluorosulfuryl isocyanate (FSOâ‚‚NCO), is highly suited for library synthesis due to its high reliability and near-quantitative yields under practical conditions [17] [21]. A recent "double-click" strategy enables sequential ligations of widely available carboxylic acids and amines via a modular amidation/SuFEx process, efficiently generating diverse libraries of N-fluorosulfonyl amides and N-acylsulfamides in 96-well microtiter plates [21]. The key is selecting click reactions known for their robustness and functional group tolerance to ensure high success rates across a wide range of building block combinations.

Advanced Troubleshooting: Competing States and Negative Design

In the context of competing states research, a primary challenge is ensuring the click reaction proceeds along the desired pathway without being diverted by side reactions or off-target interactions. The following guide addresses failures stemming from such competing states.

Problem: Competing Thiol Interference in Live Cells

- Root Cause: Endogenous thiols, particularly cysteine residues on protein surfaces, can act as nucleophiles and add across alkynes, creating a competing state that diverts the reaction from the desired azide-alkyne cycloaddition [20].

- Negative Design Solution: Proactively design the experiment to eliminate this competing pathway. Pre-treat cells with a low concentration of hydrogen peroxide (e.g., 0.1%) for approximately one minute before introducing the clickable probes. This mild oxidation shields the thiol groups, drastically reducing this interference and increasing co-localization efficiency, as demonstrated by a rise in Pearson's correlation from 0.61 to 0.89 in model studies [20].

Problem: Insufficient Driving Force Leading to Slow Kinetics

- Root Cause: The uncatalyzed Huisgen cycloaddition between azides and alkynes is thermodynamically favorable but kinetically slow at physiological temperatures, allowing for other slow, deleterious processes to occur.

- Negative Design Solution: Employ a "spring-loaded" driving force that outcompetes side reactions. Two primary strategies are:

- Catalysis: Use the CuAAC reaction, where the copper(I) catalyst accelerates the reaction by orders of magnitude, making it the dominant pathway [17] [19].

- Strain-Release: Use metal-free alternatives like SPAAC, where the relief of ring strain in cyclooctynes provides a powerful thermodynamic driving force for the reaction with azides, ensuring rapid and specific coupling in living systems without cytotoxicity [19].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Core Protocol: Cu(I)-Catalyzed Azide-Alkyne Cycloaddition (CuAAC) for Bioconjugation

This is the paradigmatic click reaction, ideal for in vitro bioconjugation due to its high selectivity and yield [17] [19].

Materials & Reagents:

- Azide-functionalized molecule (e.g., 50 nmol)

- Alkyne-functionalized molecule (e.g., 50 nmol)

- Copper(II) sulfate pentahydrate (CuSO₄·5H₂O)

- Sodium ascorbate

- tris((1-benzyl-1H-1,2,3-triazol-4-yl)methyl)amine (TBTA) ligand (optional, enhances Cu(I) stability)

- tert-Butanol

- Water (HPLC grade)

- Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS, 1x, pH 7.4)

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Preparation of Reaction Mixture: In a 1.5 mL microcentrifuge tube, dissolve the azide and alkyne building blocks in a 1:1 (v/v) mixture of tert-butanol and PBS (pH 7.4) to a final concentration of 1-10 mM each.

- Catalyst Addition: To the above solution, add CuSOâ‚„ from a freshly prepared stock solution (10-50 mM in water) to a final concentration of 1 mM.

- Reduction and Catalysis: Immediately add sodium ascorbate from a fresh 100 mM stock (in water) to a final concentration of 5 mM. This reduces Cu(II) to the active Cu(I) state. For sensitive applications, including TBTA ligand (final conc. 100 µM) to stabilize Cu(I) and prevent precipitation.

- Incubation: Cap the tube and incubate the reaction mixture at room temperature or 37 °C with gentle shaking or rotation for 1-4 hours.

- Purification: The reaction is typically complete within this time. Purify the triazole product using an appropriate method such as dialysis, size-exclusion chromatography, or precipitation to remove copper salts and other small molecules.

- Validation: Analyze the product via HPLC, MS, or NMR to confirm identity and purity.

Advanced Protocol: Double-Click Library Synthesis via SuFEx/Amidation

This protocol, adapted from recent literature, enables the high-throughput synthesis of diverse chemical libraries from carboxylic acids and amines, showcasing modularity [21].

Materials & Reagents:

- Building Blocks: Diverse carboxylic acids and amines.

- Core Reagent: Fluorosulfuryl isocyanate (FSOâ‚‚NCO).

- Solvent: Anhydrous dichloromethane (DCM) or dimethylformamide (DMF).

- Base: e.g., Triethylamine (TEA).

- Equipment: 96-well microtiter plates, inert atmosphere glove box (optional).

Step-by-Step Procedure:

First Click - Amidation:

- In each well of a 96-well plate, dispense a unique carboxylic acid (e.g., 0.1 mmol in 100 µL anhydrous DCM).

- Add FSOâ‚‚NCO (1.2 equiv) to each well, followed by a base like TEA (1.5 equiv).

- Seal the plate and incubate at room temperature for 1-2 hours with shaking. This forms the N-fluorosulfonyl amide intermediate quantitatively.

Second Click - SuFEx:

- To each well containing the intermediate, add a unique amine building block (R'R''NH, 1.2 equiv).

- Reseal the plate and continue incubation at room temperature for 1-2 hours.

Work-up:

- The N-acylsulfamide products typically form in near-quantitative yields. Evaporate the solvent under a stream of nitrogen or by centrifugal evaporation.

- Redissolve the products in DMSO or an appropriate buffer for direct biological screening (e.g., for antimicrobial activity) [21].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

| Reagent / Material | Function / Description | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Copper(I) Catalysts [17] [19] | Essential for catalyzing the classic CuAAC reaction, dramatically accelerating the cycloaddition. | Cytotoxic in living cells. Use with stabilizing ligands like TBTA for in vitro work. Not suitable for live-cell labeling. |

| Strained Cyclooctynes (e.g., DIBO) [19] | Metal-free reagents for SPAAC; ring strain drives reaction with azides. | Essential for live-cell applications. Larger molecular weight may influence probe pharmacokinetics. |

| Fluorosulfuryl Isocyanate (FSOâ‚‚NCO) [21] | A versatile SuFEx hub reagent for sequential ligations with carboxylic acids and amines. | Handle with care in appropriate chemical fume hood. Enables highly modular library synthesis. |

| Diazirine Photo-affinity Probes [20] | Photo-crosslinking groups that form covalent bonds with proximal proteins upon UV light activation (~365 nm). | Superior to benzophenones. Critical for capturing weak protein-ligand interactions for target ID. |

| Tetrazine Probes [19] | React rapidly with strained alkenes (e.g., trans-cyclooctene) in IEDDA reactions, the fastest bioorthogonal click reaction. | Enables ultra-fast labeling in vivo. Useful for pre-targeting strategies. |

| Hydrogen Peroxide (Low Conc.) [20] | A pre-treatment shield to oxidize interfering cellular thiols (e.g., cysteine), reducing false positives in click reactions. | Use at low concentrations (e.g., 0.1%) for short durations (~1 min) to avoid cellular stress. |

| Mc-MMAD | Mc-MMAD, MF:C51H77N7O9S, MW:964.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| CCR7 antagonist 1 | CCR7 antagonist 1, MF:C13H22N6OS, MW:310.42 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What is the fundamental difference between traditional inhibition and Targeted Protein Degradation (TPD)? Traditional small-molecule inhibitors operate through occupancy-driven pharmacology, where the drug binds to an active site or pocket to block protein function [22] [23]. In contrast, TPD strategies, like PROTACs, utilize event-driven pharmacology, where the drug molecule acts catalytically to recruit the cellular machinery to mark the target protein for complete degradation. The key distinction is inhibiting function versus removing the protein entirely [22] [24].

Why are some proteins considered "undruggable" by conventional methods, and how do PROTACs overcome this? An estimated 85% of the human proteome is considered "undruggable" by conventional small molecules because many disease-causing proteins, such as transcription factors, scaffolding proteins, and mutant oncoproteins, lack well-defined binding pockets [25] [24]. PROTACs overcome this by not requiring a functional binding site; they only need a surface to bind to, thereby enabling the degradation of proteins that lack conventional enzymatic activity [22] [23].

What is the "hook effect" and how can I mitigate it in my PROTAC experiments? The "hook effect" is a phenomenon observed with heterobifunctional degraders like PROTACs where, at high concentrations, the degradation efficiency paradoxically decreases [22] [24] [23]. This occurs because high concentrations of the PROTAC saturate the binding sites of either the target protein or the E3 ligase, preventing the formation of the productive ternary complex needed for ubiquitination [23]. To mitigate this, researchers should perform careful dose-response experiments to identify the optimal concentration range for degradation and avoid using PROTACs at excessively high concentrations [22].

How do I decide between using a PROTAC and a Molecular Glue Degrader? The choice depends on the target, desired properties, and discovery strategy. The table below summarizes the key differences to guide your decision [24] [23]:

Table: Comparison of PROTACs and Molecular Glue Degraders

| Feature | PROTACs | Molecular Glues (MGDs) |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Structure | Bifunctional / Heterobifunctional | Monovalent (single molecule) |

| Linker | Required | Linker-less |

| Molecular Weight | Higher (typically 700-1200 Da) | Lower (typically <500 Da) |

| Oral Bioavailability | Often challenging | Generally improved |

| Blood-Brain Barrier Penetration | More challenging | Generally better for CNS targets |

| Discovery Strategy | More rational design, linker optimization | Historically serendipitous; increasingly rational/AI-driven |

| Mechanism of Action | Brings two pre-existing binding sites into proximity | Induces or stabilizes a new protein-protein interface |

What are the most commonly used E3 ligases in TPD, and why? The most frequently recruited E3 ligases in current TPD platforms are Cereblon (CRBN) and Von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) [25] [24]. This is largely because their ligands are well-characterized, have favorable structure-activity relationships, and are synthetically accessible [22]. Other E3 ligases used include MDM2 and IAPs (e.g., for SNIPERs), but expanding the repertoire of usable E3 ligases is an active area of research to enhance tissue selectivity and overcome resistance [22] [24].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Problem: Poor or No Target Protein Degradation This is a common issue with several potential root causes and solutions.

Table: Troubleshooting Poor or No Target Protein Degradation

| Possible Cause | Suggested Experiments & Solutions |

|---|---|

| Inefficient Ternary Complex Formation | Confirm target engagement and ternary complex formation using assays like NanoBRET [25] [26]. Consider optimizing the linker length and composition to achieve a productive spatial orientation [22] [25]. |

| Insufficient Ubiquitination | Verify polyubiquitination of the target protein using ubiquitination-specific western blots or mass spectrometry [26] [27]. Ensure the E3 ligase is expressed in your cell model. |

| Inactive Ubiquitin-Proteasome System (UPS) | Test proteasome activity using a control substrate. Treat cells with a known proteasome inhibitor (e.g., MG-132) to see if it blocks the degradation caused by your degrader [26]. |

| "Hook Effect" | Perform a full dose-response curve (e.g., from 1 nM to 10 µM) to identify the optimal concentration, which may be lower than you think [23]. |

| Poor Cell Permeability | This is a known challenge for larger PROTACs [24]. Use cell-permeable positive controls. Consider alternative delivery systems like nanoparticles or electroporation for in vitro experiments [23]. |

Problem: Off-Target Degradation or Cytotoxicity Unintended protein degradation can lead to misleading results and toxic side effects.

- Confirm Specificity: Use proteomic-wide techniques, such as mass spectrometry-based proteomics, to profile global protein level changes after degrader treatment. This identifies off-target degradation events [23] [27].

- Validate On-Target Effects: Use a combination of genetic (e.g., CRISPR knockout of the target protein) and pharmacological (e.g., a competitive inhibitor) controls to confirm that the observed phenotype is due to the degradation of your specific target.

- Check E3 Ligase Specificity: The promiscuous nature of some E3 ligase ligands can lead to off-target degradation. Consider trying a PROTAC that recruits a different E3 ligase [23].

Problem: Inconsistent Results Between Replicates or Cell Lines

- Verify Expression Levels: Confirm that both your target protein and the recruited E3 ligase are adequately expressed in the cell line being used. Variability in E3 ligase expression is a common source of inconsistency [27].

- Monitor Protein Turnover: Assess the natural half-life of your target protein. Proteins with long half-lives may require longer treatment times to observe significant degradation.

- Ensure Reagent Stability: Check the stability of your PROTAC or molecular glue in the cell culture medium and prepare fresh stocks or use proper storage conditions.

Experimental Protocols for Key TPD Experiments

Protocol 1: Assessing Degradation Efficiency and Kinetics

Aim: To quantitatively measure the reduction in the level of the target protein over time following treatment with a degrader molecule.

Materials:

- Cells expressing the target protein and the relevant E3 ligase.

- PROTAC or Molecular Glue Degrader (prepare a stock solution in DMSO or appropriate solvent).

- DMSO vehicle control.

- Known inhibitor of the target (optional, for comparison).

- Proteasome inhibitor (e.g., MG-132, as a control).

- Lysis Buffer (e.g., RIPA buffer with protease and phosphatase inhibitors).

- BCA or Bradford Protein Assay Kit.

- SDS-PAGE and Western Blot equipment.

- Antibodies against the target protein and a loading control (e.g., GAPDH, Actin).

Method:

- Cell Seeding and Treatment: Seed cells in multi-well plates and allow them to adhere overnight. Treat cells with the degrader at various concentrations (e.g., 0.1 nM, 1 nM, 10 nM, 100 nM, 1 µM) and for different time points (e.g., 1, 2, 4, 8, 12, 24 hours). Include DMSO-only treated wells as a negative control and wells co-treated with a proteasome inhibitor to confirm UPS dependence.

- Cell Lysis: At each time point, lyse the cells in an appropriate lysis buffer. Centrifuge the lysates to remove debris.

- Protein Quantification: Determine the protein concentration of each lysate using a colorimetric assay (e.g., BCA assay) to ensure equal loading.

- Western Blotting: Separate equal amounts of protein by SDS-PAGE and transfer to a nitrocellulose or PVDF membrane. Block the membrane and probe with the primary antibody against your target protein, followed by a horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibody. Develop the blot using a chemiluminescent substrate and image.

- Data Analysis: Quantify the band intensity of the target protein and normalize it to the loading control. Plot the percentage of protein remaining versus time and concentration to determine the DC50 (concentration that degrades 50% of the target protein) and Dmax (maximum degradation achieved) values.

Protocol 2: Confirming Ternary Complex Formation

Aim: To demonstrate that the degrader molecule simultaneously binds both the target protein and the E3 ubiquitin ligase, forming a ternary complex.

Materials:

- Recombinant, purified target protein and E3 ligase complex (e.g., CRBN-DDB1).

- PROTAC molecule.

- NanoBRET Ternary Complex Assay Kit (or similar technology) [25] [26].

- Microplate reader capable of measuring BRET.

Method (Using a Live-Cell NanoBRET Assay):

- Cell Transfection: Transfect cells with plasmids expressing the target protein fused to a NanoLuc luciferase donor and the E3 ligase fused to a HaloTag acceptor.

- Ligand Labeling: Label the HaloTag-E3 ligase fusion protein in live cells with a cell-permeable HaloTag NanoBRET ligand.

- PROTAC Treatment: Treat the cells with your PROTAC molecule across a range of concentrations.

- BRET Measurement: Add the NanoLuc substrate and measure the energy transfer (BRET ratio) between the donor and acceptor using a compatible microplate reader. The formation of the ternary complex brings the donor and acceptor into close proximity, resulting in a increased BRET ratio.

- Data Analysis: Plot the BRET ratio against the log of the PROTAC concentration to generate a binding curve and calculate an EC50 value for ternary complex formation.

Protocol 3: Validating Ubiquitination of the Target Protein

Aim: To confirm that the target protein is polyubiquitinated in a degrader-dependent manner.

Materials:

- Cells (as in Protocol 1).

- PROTAC or Molecular Glue Degrader.

- Proteasome inhibitor (MG-132).

- Lysis Buffer (strong denaturing buffer, e.g., with 1% SDS, to preserve ubiquitination).

- IP Lysis/Wash Buffer (non-denaturing).

- Antibody against the target protein for immunoprecipitation (IP).

- Agarose beads (e.g., Protein A/G).

- Ubiquitin detection antibody (can be specific for polyubiquitin chains or tagged ubiquitin, e.g., HA-Ubiquitin).

- Standard Western Blot equipment.

Method (Co-Immunoprecipitation and Ubiquitin Western Blot):

- Cell Treatment and Lysis: Treat cells with the degrader, a DMSO control, and a condition with both degrader and MG-132 (to accumulate ubiquitinated proteins). Use a denaturing lysis buffer to quickly inactivate deubiquitinases.

- Immunoprecipitation (IP): Dilute the lysates with a non-denaturing IP buffer. Incubate the lysates with an antibody against your target protein, followed by the addition of agarose beads to pull down the target protein and its associated complexes.

- Washing and Elution: Wash the beads thoroughly to remove non-specifically bound proteins. Elute the bound proteins by boiling in SDS-PAGE sample buffer.

- Western Blot Analysis: Resolve the eluted proteins by SDS-PAGE and transfer to a membrane. Probe the membrane with an anti-ubiquitin antibody. A "smear" of higher molecular weight bands above the expected size of the target protein indicates successful polyubiquitination. Re-probing the blot with the target protein antibody can serve as a loading control for the IP.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

This table details key reagents and tools essential for conducting TPD research, as highlighted in the search results [26] [27].

Table: Essential Research Reagents for Targeted Protein Degradation

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Explanation | Example Use Cases |

|---|---|---|

| Degrader Building Blocks | Commercially available ligands for target proteins and E3 ligases, with diverse linkers. Used for the rational design and synthesis of novel PROTAC molecules [27]. | Custom PROTAC synthesis; linker optimization studies. |

| TAG Degradation Systems (dTAG, aTAG, BromoTag) | A validated platform that uses a synthetic degron fused to a target protein and a complementary "TAG degrader". Allows for rapid, reversible, and selective degradation of the tagged protein, ideal for target validation [27]. | Validation of new drug targets; study of acute protein loss phenotypes. |

| E3 Ligase Proteins & Assays | Highly active, purified recombinant E3 ubiquitin ligases (e.g., VHL, CRBN, DCAF proteins) and assay kits to study their activity and engagement. Crucial for in vitro biochemical characterization of degraders [27]. | In vitro ubiquitination assays; screening for new E3 ligase ligands. |

| Ternary Complex Assays (e.g., NanoBRET) | Live-cell assays that quantitatively measure the formation of the PROTAC-induced complex between the target protein and the E3 ligase. Provides critical data on binding affinity and cooperativity [25] [26]. | Optimizing PROTAC design; mechanistic studies of degradation efficiency. |

| Ubiquitin Detection Kits | Kits containing antibodies and reagents specifically designed to detect protein polyubiquitination via western blot or other immunoassays. Confirms the key step marking the protein for degradation [26] [27]. | Confirming on-target ubiquitination; investigating mechanisms of resistance. |

| Global Proteomics Services | Mass spectrometry-based services (e.g., using DIA technology) for deep, unbiased profiling of the entire cellular proteome. The gold standard for assessing degrader selectivity and off-target effects [23] [27]. | Comprehensive assessment of degrader selectivity; identification of novel degradation targets. |

| Tas-121 | Tas-121, CAS:1451370-01-6, MF:C22H20N6O, MW:384.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| (R)-9b | (R)-9b, CAS:1655527-68-6, MF:C20H27ClN6O, MW:402.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Key Experimental Workflows and Pathway Diagrams

Diagram 1: PROTAC Experimental Workflow. A generalized workflow for the design, synthesis, and validation of PROTAC molecules, from initial assembly to cellular phenotypic assessment.

Diagram 2: PROTAC Mechanism of Action. The catalytic cycle of a PROTAC molecule, from inducing ternary complex formation to target ubiquitination, degradation, and PROTAC recycling.

Structure-Based Drug Design (SBDD) to Anticipate and Avoid Off-Target Binding

Structure-Based Drug Design (SBDD) represents a cornerstone of modern rational drug discovery, utilizing three-dimensional structural information of biological targets to design therapeutic molecules [28]. A critical advancement in this field is the paradigm of negative design, a strategy that explicitly considers and avoids undesirable interactions—particularly off-target binding—during the molecular design process. This approach directly addresses one of the primary causes of clinical trial failure, where approximately 20–25% of drug candidates fail due to safety concerns arising from off-target effects [29].

Negative design operates on the principle of competing states research, which systematically analyzes and designs against alternative, undesired binding modes. Rather than solely optimizing for affinity toward a primary target, this methodology requires the simultaneous prediction and avoidance of interactions with structurally similar off-target proteins. The integration of computational advances, including deep learning generative models and large-scale docking, now provides unprecedented capability to implement negative design strategies proactively, moving beyond traditional reactive approaches that identified toxicity issues only after significant investment [29] [30].

Key Concepts and Terminology

Off-Target Binding: The unintended interaction of a drug candidate with proteins other than its primary therapeutic target, often leading to adverse effects and toxicity [29].