Navigating the Unknown: A Practical Guide to Handling Out-of-Distribution Protein Sequences in Biomedical Research

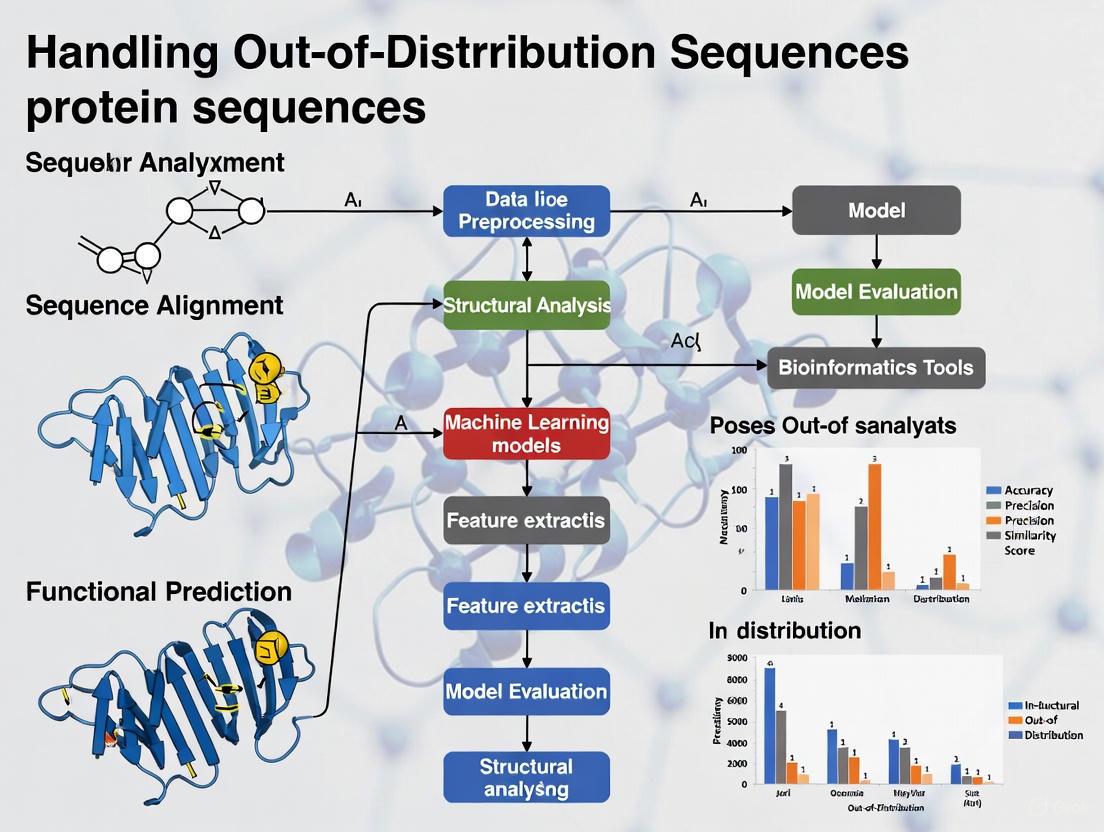

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on managing out-of-distribution (OOD) protein sequences—data that significantly differs from a model's training examples.

Navigating the Unknown: A Practical Guide to Handling Out-of-Distribution Protein Sequences in Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on managing out-of-distribution (OOD) protein sequences—data that significantly differs from a model's training examples. We explore the fundamental concepts and critical importance of OOD detection in protein science, detail cutting-edge methodological frameworks for identification and analysis, offer troubleshooting strategies for common challenges, and present validation protocols for assessing model performance. By synthesizing the latest advances from anomaly detection to specialized deep learning architectures, this resource aims to enhance the reliability and predictive power of computational methods when encountering novel protein sequences in real-world biomedical applications.

What Are OOD Protein Sequences and Why Do They Challenge Our Models?

Defining Out-of-Distribution Data in the Context of Protein Sequences

Frequently Asked Questions

1. What does "Out-of-Distribution" (OOD) mean for protein sequence data?

In machine learning for proteins, In-Distribution (ID) data refers to protein sequences that share similar characteristics and come from the same underlying distribution as the sequences used to train a model. Conversely, Out-of-Distribution (OOD) protein sequences come from a different, unknown distribution that the model did not encounter during training [1] [2]. This is a critical concept because models often make unreliable predictions on OOD data, which can lead to experimental dead-ends if not properly identified.

2. Why is detecting OOD protein sequences so important in research and drug discovery?

OOD detection is vital for ensuring the reliability of computational predictions in biology. When models trained on known proteins are applied to the vast "dark" regions of protein space—where sequences have no known ligands or functions—they frequently encounter OOD samples [3]. For example, in drug discovery, a model might confidently but incorrectly predict that a compound will bind to a "dark" protein, leading to wasted experimental resources. Accurately identifying these OOD sequences helps researchers gauge prediction reliability and avoid false positives [1] [4].

3. What are the main challenges in predicting the function or structure of OOD proteins?

The primary challenge is the fundamental limitation of machine learning models to generalize beyond their training data. Key specific issues include:

- Over-estimation of Confidence: Models can assign high confidence scores to OOD predictions that are actually incorrect [1].

- Inability to Model Dynamics: Current AI-based structure prediction tools often provide static structural models and cannot capture the conformational changes and dynamics intrinsic to protein function, especially for novel sequences [5].

- Limitations with Multi-chain Complexes: Predicting the structure of multi-protein complexes is significantly less accurate than single-chain prediction, and performance degrades as complex size increases, making many functional assemblies OOD challenges [5].

4. Are 'Out-of-Domain' and 'Out-of-Distribution' the same for protein data?

No, they are related but distinct concepts. Out-of-Domain refers to data that is fundamentally outside the scope or intended use of a model. For a model trained only on human proteins, bacterial proteins would be Out-of-Domain. Out-of-Distribution, however, refers to data within the same broad domain (e.g., human proteins) but that follows a different statistical distribution, such as a protein from a novel gene family not seen during training [2]. Most Out-of-Domain data will also be OOD.

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: High False Positive Rates in Virtual Screening

Problem: Your virtual screening pipeline, using a model trained on known protein-ligand pairs, identifies many hits that fail experimental validation. These false positives may be due to the model processing OOD proteins or compounds.

Solution:

- Implement an OOD Detector: Integrate a method like MLR-OOD to flag potential OOD sequences before conducting virtual screens. MLR-OOD uses a likelihood ratio to distinguish ID from OOD sequences without needing a separate validation set of OOD data [1].

- Adopt Sequence-First Models: For proteins with poor or no structural data, use a sequence-based drug design tool like TransformerCPI2.0. This approach predicts compound-protein interactions directly from sequence, bypassing error-prone structural modeling steps that are vulnerable to OOD issues [4].

- Validate with Safe Optimization: When designing new protein variants, use frameworks like MD-TPE (Mean Deviation Tree-structured Parzen Estimator). This method incorporates predictive uncertainty from a model (like a Gaussian Process) to penalize and avoid exploring unreliable OOD regions of protein sequence space, focusing the search on areas near known functional sequences [6].

Issue 2: Poor Generalization to Novel Protein Families ("Dark Proteins")

Problem: Your model performs well on proteins similar to its training set but fails to accurately predict the function or ligands for proteins from understudied, non-homologous gene families.

Solution:

- Utilize Meta-Learning Frameworks: Employ the PortalCG framework. It is specifically designed for this "out-of-gene-family" scenario through several key innovations [3]:

- Sequence Pre-training: It uses a 3D ligand binding site-enhanced pre-training strategy to encode evolutionary links.

- Meta-Learning: An out-of-cluster meta-learning algorithm extracts information from predicting ligands in distinct gene families and applies it to a dark gene family.

- Stress Testing: The model is selected based on its performance on test data from different gene families than the training data.

- Incorporate Evolutionary Information: Leverage deep generative models that are pre-trained on large, diverse sequence datasets to build richer, more generalizable representations that are less likely to be "surprised" by a novel sequence [3] [7].

Experimental Protocols for OOD Detection

This section provides a detailed methodology for benchmarking OOD detection methods on protein sequence data, based on established research [1].

Protocol: Benchmarking an OOD Detection Method on a Bacterial Genome Dataset

1. Objective To evaluate the performance of an OOD detection method in distinguishing In-Distribution (ID) bacterial genera from Out-of-Distribution (OOD) bacterial genera.

2. Materials and Data Preparation

- Data Source: Download bacterial genomes from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI).

- Sequence Generation: Chop the genomes into short, non-overlapping sequences (e.g., 250 base pairs).

- Define ID/OOD Classes:

- ID Classes: Select sequences from a specific set of bacterial genera (e.g., 10 genera discovered before 01/01/2011).

- OOD Classes: Select sequences from a different set of genera (e.g., 60 genera not used for ID classes).

- Split Datasets: Partition the data into training, validation, and testing sets, ensuring no genera overlap between ID and OOD sets. Using discovery dates can help create a realistic time-split.

3. Step-by-Step Procedure

- Train a Classifier: Train a taxonomic classification model (e.g., a deep neural network) on the sequences from the ID classes.

- Extract Likelihoods: For a given test sequence, obtain the likelihoods from generative models for each ID class.

- Calculate the MLR-OOD Score: Compute the Markov chain-based likelihood ratio. The formula used in MLR-OOD is [1]:

MLR-OOD Score = max( ID Class Conditional Likelihoods ) / Markov Chain Likelihood of the sequenceA high score indicates the sequence is likely ID, while a low score suggests it is OOD. - Evaluate Performance: Generate a Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve and calculate the Area Under the ROC curve (AUROC) to quantify how well the method separates ID and OOD sequences.

5. Expected Output The primary output is an AUROC value. A higher AUROC (closer to 1.0) indicates better OOD detection performance. The method should be robust to confounding factors like varying GC content across genera [1].

Comparison of OOD Detection Methods

The table below summarizes key methods discussed for handling OOD challenges in protein science.

| Method Name | Primary Application | Key Principle | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| MLR-OOD [1] | Metagenomic Sequence Classification | Likelihood ratio between class likelihoods and sequence complexity. | No need for a separate OOD validation set for parameter tuning. |

| PortalCG [3] | Ligand Prediction for Dark Proteins | End-to-end meta-learning from sequence to function. | Designed for out-of-gene-family prediction, generalizes to dark proteins. |

| MD-TPE [6] | Protein Engineering & Design | Penalizes optimization in high-uncertainty (OOD) regions of sequence space. | Enables safe, reliable exploration near known functional sequences. |

| TransformerCPI2.0 [4] | Compound-Protein Interaction Prediction | Directly predicts interactions from sequence, avoiding structural models. | Bypasses OOD issues associated with predicted or low-quality protein structures. |

Research Reagent Solutions

This table lists essential computational tools and resources for researchers working with OOD protein sequences.

| Item | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| AlphaFold Protein Structure Database [5] | Provides open access to millions of predicted protein structures for analysis and as a potential training resource. |

| ESM Metagenomic Atlas [5] | Offers a vast collection of predicted structures for metagenomic proteins, expanding the known structural space. |

| 3D-Beacons Network [5] | A centralized platform providing standardized access to protein structure models from multiple resources (AlphaFold DB, PDB, etc.). |

| CHEAP Embeddings [7] | A compressed, joint representation of protein sequence and structure from models like ESMFold, useful for efficient downstream analysis. |

| Gaussian Process (GP) Model [6] | A proxy model used in optimization tasks that provides a predictive mean and deviation, crucial for quantifying uncertainty in methods like MD-TPE. |

The Real-World Consequences of OOD Brittleness in Biomedical Applications

Welcome to the Technical Support Center for Out-of-Distribution (OOD) Robustness in Biomedical Research. This resource addresses the critical challenge of OOD brittleness—when machine learning models and analytical tools perform poorly on data that differs from their training distribution. In protein research, this manifests as unreliable predictions for sequences with novel folds, unseen domains, or unusual compositional properties not represented in training datasets. Our troubleshooting guides and FAQs provide practical solutions for researchers encountering these issues, framed within the broader thesis that proactive OOD detection and handling is essential for robust, generalizable protein science and drug development.

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Diagnosing Poor Model Performance on Novel Protein Sequences

Problem: Your predictive model (e.g., for structure, function, or stability) performs well on validation data but fails on your novel protein sequences.

Symptoms:

- High confidence predictions that are objectively incorrect

- Large prediction variances across similar sequences

- Performance degradation on sequences from underrepresented species or protein families

Diagnostic Steps:

- Run OOD Detection Algorithms: Incorporate OOD detection as a prescreening step. Effective OOD detectors can identify patient or sample subsets where your model is likely to be unreliable because the data differs from the training distribution [8]. Use these detectors to flag problematic sequences before full analysis.

- Stratified Performance Analysis: Slice your performance metrics by data subgroups. Check if performance drops correlate with specific:

- Taxonomic Groups: Sequences from underrepresented species.

- Protein Families: Sequences from novel subfamilies not in training.

- Sequence Features: Unusual amino acid composition or domain architectures.

- Check Dataset Shift Origin: Investigate the source of distribution shift:

- Covariate Shift: Has the distribution of input features (e.g., amino acid frequencies) changed?

- Semantic Shift: Are there new, unseen classes of proteins in your test set?

Guide 2: Handling Unreliable Automated Protein Function Annotations

Problem: Automated annotation tools (e.g., InterProScan) provide inconsistent, conflicting, or low-confidence matches for your protein sequence.

Symptoms:

- Missing domain annotations for known protein families

- Contradictory functional predictions from different member databases

- Low-confidence scores or E-values for matches that appear valid

Troubleshooting Steps:

- Verify Input Sequence Quality: Ensure your sequence is not fragmentary or of poor quality. Degraded input can produce unreliable results.

- Consult Hierarchical Evidence: In InterPro, a match is more trustworthy if multiple signatures within the same entry or hierarchy support it. The more signatures that agree, the more confident you can be in the annotation [9].

- Inspect Unintegrated Signatures: Be cautious of matches to "unintegrated" signatures, as they may not have undergone the same level of curation and could produce false positives [9].

- Leverage OOD for Data Filtering: If you are performing large-scale proteome or genome annotation, use OOD detection to identify sequences where automated annotation pipelines are likely to fail. Flag these sequences for manual curation or more intensive analysis [8].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What exactly is "OOD Brittleness" in the context of protein sequence research?

OOD brittleness refers to the sharp degradation in performance of computational models when they encounter protein sequences that are statistically different from those they were trained on. This can include sequences with novel folds, domains from underrepresented evolutionary families, unusual amino acid compositions, or from organisms not included in the training data. Since models are often trained on limited, controlled datasets, this brittleness poses a significant risk in real-world applications where data is inherently heterogeneous [8].

FAQ 2: What are the main types of distribution shifts I should be concerned with?

The table below summarizes key robustness concepts relevant to biomedical research [10].

| Robustness Type | Description | Example in Protein Research |

|---|---|---|

| Group/Subgroup Robustness | Performance consistency across subpopulations. | Model performance on protein families underrepresented in training data. |

| Out-of-Distribution Robustness | Resistance to semantic or covariate shift from training data. | Performance on sequences with novel folds or from newly sequenced organisms. |

| Vendor/Acquisition Robustness | Consistency across data sources or protocols. | Consistency of predictions when using sequences from different sequencing platforms. |

| Knowledge Robustness | Consistency against perturbations in knowledge elements. | Reliability when protein knowledge graphs are incomplete or contain nonstationary data. |

FAQ 3: My model has high overall accuracy. Why should I worry about OOD samples?

In a large population, the poor performance on a small number of OOD samples can be easily overlooked because its effect on the overall performance metric is trivial [8]. However, this deficiency can have severe consequences. For example, if your model is used for therapeutic protein design, failure on a specific, rare OOD class could lead to designed proteins that are unstable or non-functional. Stratified analysis is necessary to uncover these hidden failures [8].

FAQ 4: Are some protein scaffolds more susceptible to OOD issues than others?

Yes. Some protein structures are more sensitive to packing perturbations, meaning that changes in the amino acid sequence (even if they are functionally neutral) can disrupt folding pathways and lead to misfolding or aggregation. Computationally, such scaffolds can be identified as having low robustness to sequence permutations. This sensitivity can make them poor choices for protein engineering, as finding a sequence that folds correctly onto the scaffold becomes difficult [11].

FAQ 5: What is a concrete experimental method to assess a protein scaffold's robustness?

Method: The Random Permutant (RP) Method [11]

Aim: To computationally assess how a protein structure responds to packing perturbations, which is a proxy for its robustness and potential OOD brittleness.

Protocol:

- Generate Random Permutants: Create random permutations of your protein's wild-type (WT) sequence. This keeps the backbone structure identical but perturbs the side-chain packing (e.g., large side chains are replaced by small ones and vice versa).

- Create Structure-Based Models (SBMs): Develop coarse-grained SBMs for both the WT and the RP proteins. These models have funneled energy landscapes that encode the target folded structure.

- Run Folding Simulations: Perform multiple folding simulations using the SBMs for both WT and RP proteins.

- Analyze Folding Cooperativity: Compare the folding pathways. A robust, well-designed scaffold will maintain cooperative (all-or-nothing) folding in the RP simulations. A brittle scaffold will show populated folding intermediates, stalling, and non-cooperative folding due to the packing perturbations [11].

Visualization of the RP Method Workflow:

Performance Benchmarks & Data

Table 1: OOD Detection Performance Across Medical Data Modalities Data from a simulated training-deployment scenario evaluating state-of-the-art OOD detectors on three medical datasets. Effective detectors identify subsets with worse model performance [8].

| Data Modality | Task | Model Performance (ID vs OOD) | OOD Detector Efficacy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dermoscopy Images | Melanoma Classification | Performance degradation on data from new hospital centers | Multiple detectors consistently identified patients with worse model performance [8]. |

| Parasite Transcriptomics | Artemisinin Resistance Prediction | Performance drop when deploying in a new country (Myanmar) | OOD detectors identified patient subsets underrepresented in training [8]. |

| Smartphone Sensor (Time-Series) | Parkinson's Disease Diagnosis | Performance change on younger patients (≤45 years) | Detectors identified data slices with higher prediction variance and poor performance [8]. |

Table 2: Benchmarking OOD Detection Methods on Medical Tabular Data Results from a large-scale benchmark on public medical datasets (e.g., eICU, MIMIC-IV) showing that OOD detection is highly challenging with subtle distribution shifts [12].

| Distribution Shift Severity | Example Scenario | Best OOD Detector AUC | Performance Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| Large, Clear Shift | Statistically distinct datasets | > 0.95 | Detectors perform well when the OOD data is easily separable from training data [12]. |

| Subtle, Real-World Shift | Splits based on ethnicity or age | ~0.5 (Random) | Many detectors fail, performing no better than a random classifier on subtle shifts [12]. |

OOD Detection Strategy Workflow

Implementing a robust OOD detection strategy involves multiple steps, from data handling to model invocation and expert review, as shown in the workflow below.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Robust Protein Research

| Tool / Resource | Function | Application in OOD Context |

|---|---|---|

| InterPro & InterProScan [9] | Integrated database for protein classification, domain analysis, and functional prediction. | Identify anomalous or low-confidence domain matches that may indicate an OOD sequence. |

| OpenProtein.AI PoET (Rank Sequences) [13] | Tool for scoring and ranking protein sequence fitness relative to a multiple sequence alignment (prompt). | Assess how "atypical" a new sequence is compared to a known family (MSA), quantifying its OOD nature. |

| Random Permutant (RP) Method [11] | Computational method using structure-based models to assess a protein scaffold's tolerance to sequence changes. | Identify protein scaffolds that are inherently brittle and prone to misfolding with sequence variations. |

| OOD Detection Algorithms (e.g., density-based, post-hoc) [8] [12] | Methods to detect if an observation is unlikely to be from the model's training distribution. | Prescreen data to identify sequences on which predictive models are likely to perform poorly. |

| Biomedical Foundation Models (BFMs) [10] | Large-scale models (LLMs, VLMs) trained on broad biomedical data. | Requires tailored robustness tests for distribution shifts specific to protein sequence tasks. |

| 2-(Chloromethyl)pyrimidine hydrochloride | 2-(Chloromethyl)pyrimidine hydrochloride | RUO | High-purity 2-(Chloromethyl)pyrimidine hydrochloride for research. A key pyrimidine building block for medicinal chemistry & drug discovery. For Research Use Only. |

| Trioctyl trimellitate | Tris(2-ethylhexyl) trimellitate | High Purity Plasticizer | Tris(2-ethylhexyl) trimellitate is a high-performance plasticizer for polymer research. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

Troubleshooting Guide: FAQs for OOD Protein Research

This guide addresses common challenges researchers face when working with out-of-distribution (OOD) protein sequences, particularly prion-like proteins and novel enzyme systems.

Q1: Our predictions for dark protein-ligand interactions yield high false-positive rates. How can we improve accuracy?

A: This is a common OOD challenge where proteins differ significantly from those with known ligands. We recommend:

- Implement meta-learning algorithms: Frameworks like PortalCG use out-of-cluster meta-learning to extract information from distinct gene families and apply it to dark gene families, significantly improving OOD generalization [3].

- Adopt an end-to-end sequence-structure-function approach: Instead of relying solely on predicted structures for docking, use a differentiable deep learning framework where structural information serves as an intermediate layer. This reduces the impact of structural inaccuracies on function prediction [3].

- Enhance sequence pre-training: Utilize 3D ligand binding site information during sequence pre-training to better encode evolutionary links across gene families [3].

Q2: Our cellular models for prion-like protein aggregation do not recapitulate sporadic disease onset. What factors are we missing?

A: Models dominated by seeded aggregation may overlook key aspects of sporadic disease. Consider these factors:

- Account for spontaneous formation: Aggregates can form spontaneously at a relatively high rate, particularly under cellular stress. This is a key contrast to classical prion diseases and may be a dominant factor in sporadic cases [14].

- Incorporate aggregate removal mechanisms: Resistance to seeding and aggregate removal processes are crucial for maintaining homeostasis. Runaway aggregation in disease may occur when removal can no longer keep up with production, not merely upon the first appearance of a seed [14].

- Include non-cell-autonomous triggers: Pathology spread may not require direct transfer of aggregates. Investigate indirect mechanisms, such as aggregate-induced inflammation, where cytokines from affected glia cells can disrupt protein homeostasis in nearby healthy cells [14].

Q3: How can we experimentally validate the functional regulation of a human prion-like domain identified by cryo-EM?

A: A combination of structural and cell biological methods is effective, as demonstrated in a recent CPEB3 study:

- Core segment deletion: Delete the ordered core segment (e.g., L103-F151 in hCPEB3) and compare its behavior to the wild-type protein.

- Subcellular localization analysis: Assess if the deletion variant coalesces into abnormal puncta and localizes away from its typical compartments (e.g., dormant p-bodies) toward stress-induced compartments (e.g., stress granules) [15].

- Functional phenotypic assays: Test the protein's ability to influence key downstream processes, such as protein synthesis in neurons. The deleted variant should lack this functional ability [15].

- Cellular viability assessment: Compare the viability of cells expressing the wild-type protein versus the core-deleted variant, as self-assembly can induce cellular stress and reduce viability [15].

Q4: We aim to develop novel biocatalytic methods for diversity-oriented synthesis. How can we move beyond nature's limited substrate scope?

A: Leverage the synergy between enzymatic and synthetic catalysts:

- Employ concerted enzyme-photocatalyst systems: Use sunlight-harvesting catalysts to generate reactive species that participate in a larger enzymatic catalysis cycle. This enables novel multicomponent reactions unknown in both chemistry and biology [16].

- Exploit enzymatic generality: Some enzymes, when placed in these novel reaction systems, show surprising generality and can function on a wide range of non-natural substrates, allowing for the creation of diverse molecular scaffolds [16].

- Focus on carbon-carbon bond formation: This backbone of organic chemistry is a key target for generating valuable, complex molecules with rich and well-defined stereochemistry [16].

Experimental Protocols for Key Studies

Protocol 1: Analyzing Prion-like Protein Function via Core Domain Deletion

This methodology is adapted from structural and functional studies on human CPEB3 [15].

Objective: To determine the functional role of an identified amyloid-forming core segment in a prion-like protein.

Materials:

- Cloned gene for the wild-type prion-like protein (e.g., hCPEB3)

- Plasmid for generating core segment deletion mutant (e.g., ΔL103-F151)

- Appropriate cell line (e.g., neuronal cells for CPEB3)

- Antibodies for immunofluorescence and Western blot

- Cryo-electron microscope

- Cryo-FIB milling and cryo-ET setup

Procedure:

- Construct Generation: Generate a deletion mutant of the target protein lacking the structured core segment identified by cryo-EM (e.g., residues 103-151 for CPEB3).

- Cell Transfection: Transfect cultured cells with constructs for: a) wild-type protein, b) core-deleted protein, and c) empty vector control.

- Subcellular Localization (4-6 hrs post-transfection):

- Fix cells and perform immunofluorescence staining for the target protein and markers for relevant organelles (e.g., p-body markers, stress granule markers).

- Image using super-resolution or confocal microscopy.

- Quantify: The percentage of cells showing abnormal protein puncta and co-localization coefficients with organelle markers.

- Functional Assay (24-48 hrs post-transfection):

- In neuronal cells, assess the protein's impact on global protein synthesis using a surface sensing of translation (SUnSET) assay or similar.

- Quantify: Levels of nascent protein synthesis normalized to total protein.

- Cell Viability (72 hrs post-transfection):

- Perform an MTT or similar cell viability assay.

- Quantify: Relative viability of cells expressing wild-type vs. mutant protein.

- Structural Analysis (In vitro):

- Purify the recombinant prion-like domain.

- Grow amyloid fibrils in vitro and subject them to cryo-EM for structure determination.

- In-situ Structural Analysis:

- Express the protein (e.g., fused to GFP) in cells.

- Use fluorescence-guided cryo-FIB milling to prepare thin lamellae from identified cellular regions.

- Acquire cellular tomograms using cryo-ET to visualize native-state structures in cells.

Protocol 2: PortalCG Framework for Predicting Ligands of Dark Proteins

This protocol outlines the computational workflow for predicting ligands for proteins with no known ligands (dark proteins) using the PortalCG framework [3].

Objective: To accurately predict small-molecule ligands for dark protein targets where traditional docking and ML methods fail.

Materials:

- Protein sequence of the dark target

- PortalCG software framework (available from the original publication)

- Computational resources (GPU cluster recommended)

- Databases of known protein-ligand interactions for model training and benchmarking

Procedure:

- Input and Pre-processing:

- Input the amino acid sequence of the dark target protein.

- The sequence is processed through a pre-trained language model.

- 3D Binding Site Enhancement:

- The model incorporates a 3D ligand binding site pre-training strategy. It uses evolutionary links between ligand-binding sites across gene families to enrich the sequence representation, even if the exact structure is unknown.

- End-to-End Meta-Learning:

- The framework employs an out-of-cluster meta-learning algorithm. It extracts and accumulates information (meta-data) learned from predicting ligands for distinct, well-characterized gene families.

- This meta-data is applied to the dark gene family of your target protein.

- Stress Model Selection:

- The model is evaluated using a test set containing gene families completely separate from those in the training and development sets. This step ensures robustness and generalizability for real-world OOD applications.

- Output and Validation:

- The output is a ranked list of predicted small-molecule ligands for your dark protein.

- Experimental Validation: The top-ranking predictions should be validated experimentally using binding assays (e.g., SPR, ITC) or functional cellular assays.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key reagents and their applications in the featured fields of research.

| Research Reagent | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| Base Editor (e.g., ABE, CBE) | Precision gene editing tool that chemically converts a single DNA base pair into another, used to study gene function or for therapeutic target validation [17]. |

| Adeno-Associated Virus (AAV) Vector | A delivery vehicle for introducing genetic material (e.g., base editors, target genes) into cells in vitro or in vivo with high targeting specificity [17]. |

| Cryo-Electron Microscopy (Cryo-EM) | A structural biology technique for determining high-resolution 3D structures of biomolecules, such as amyloid fibrils, in a near-native state [15]. |

| Cryo-Electron Tomography (cryo-ET) | An imaging technique that uses cryo-EM to visualize the native architecture of cellular environments and macromolecular complexes in situ [15]. |

| Reprogrammed Biocatalysts | Enzymes whose catalytic activity has been engineered or adapted for non-natural reactions, enabling diversity-oriented synthesis of novel molecules [16]. |

| Photocatalysts | Small molecules that absorb light to generate reactive species; used in concert with enzymes to create novel biocatalytic reactions [16]. |

| Meta-Learning Algorithm (PortalCG) | A deep learning framework designed to predict protein-ligand interactions for "dark" proteins that are out-of-distribution from training data [3]. |

| 2-Amino-3-methoxybenzoic acid | 2-Amino-3-methoxybenzoic Acid | High-Purity RUO |

| 20-Carboxyarachidonic acid | 5Z,8Z,11Z,14Z-Eicosatetraenedioic Acid | RUO |

Table 1: Experimental Data from Prion Disease Therapeutic Study [17]

| Experimental Metric | Result | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|

| Reduction in Prion Protein | ~63% | In mouse brains using an improved, safer AAV vector dose. |

| Lifespan Extension | 52% | In a mouse model of inherited prion disease following treatment. |

| Protein Reduction (Initial Method) | ~50% | In mouse brains using the initial base-editing approach. |

Table 2: Turnover Rates of Common Enzymes [18]

| Enzyme | Turnover Rate (mole product sâ»Â¹ mole enzymeâ»Â¹) |

|---|---|

| Carbonic Anhydrase | 600,000 |

| Catalase | 93,000 |

| β-galactosidase | 200 |

| Chymotrypsin | 100 |

| Tyrosinase | 1 |

Workflow and Pathway Visualizations

PortalCG for OOD Protein Prediction

Mechanisms of Pathology Spread in Neurodegeneration

Protein Language Models (pLMs) as a Foundation for OOD Understanding

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the primary cause of poor pLM performance on my out-of-distribution (OOD) protein sequences? The primary cause is the significant evolutionary divergence between your OOD sequences and the proteins in the pLM's pre-training dataset. pLMs learn the statistical properties of their training data; when faced with sequences from distant species (e.g., applying a model trained on human data to yeast or E. coli), the model encounters "sequence idioms" it has not seen before, leading to a drop in performance [19]. This is often compounded by using embeddings that are not optimized for the OOD context.

Q2: My computational resources are limited. Which pLM should I choose for OOD tasks? Contrary to intuition, the largest model is not always the best, especially with limited data. Medium-sized models like ESM-2 650M or ESM C 600M offer an optimal balance, performing nearly as well as their 15-billion-parameter counterparts on many OOD tasks while being far more computationally efficient [20]. Starting with a medium-sized model is a practical and scalable choice.

Q3: How can I best compress high-dimensional pLM embeddings for my downstream predictor? For most transfer learning tasks, especially with widely diverged sequences, mean pooling (averaging the embeddings across all amino acid positions) consistently outperforms other compression methods like max pooling or iDCT [20]. It provides a robust summary of the global sequence properties, which is particularly valuable for OOD generalization.

Q4: What are the essential checks for a protein sequence generated or designed by a pLM before laboratory testing? Before costly wet-lab experiments, you should perform a suite of sequence-based and structure-based evaluations [21]:

- Sequence-based: Check for degenerate sequences (e.g., short amino acid motifs repeated consecutively), verify the sequence starts with a methionine ('M'), ensure the length is within a plausible range (e.g., 70%-130% of a reference protein's length), and use tools like BLAST or HMMer to confirm similarity to the target protein family.

- Structure-based: Use AlphaFold2 or ESMFold to predict the 3D structure. Then, calculate metrics like the TM-score against a reference structure to check global fold preservation and use tools like DSSP to verify that the order of secondary structure elements (alpha-helices, beta-sheets) is conserved [21].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Low Cross-Species Prediction Accuracy

Problem: Your pLM-based predictor, trained on data from one species (e.g., human), shows significantly degraded performance when applied to other species (e.g., mouse, fly, yeast).

Diagnosis and Solutions:

- Diagnosis: The model has learned species-specific interaction patterns or features that do not generalize. This is common in tasks like Protein-Protein Interaction (PPI) prediction.

- Solution 1 - Use a Joint-Encoding Architecture: Move beyond using static, pre-computed embeddings for single proteins. Instead, use a model like PLM-interact, which is fine-tuned to jointly encode pairs of interacting proteins. This allows the model to learn the context of interaction directly, much like "next-sentence prediction" in NLP, leading to superior cross-species generalization [19].

- Solution 2 - Leverage Structural Similarity: If joint training is not feasible, use a structure-aware search tool like TM-Vec. TM-Vec can find structurally similar proteins in large databases directly from sequence, helping to bridge the gap for remotely homologous OOD sequences that sequence-based tools like BLAST might miss [22].

Recommended Experimental Protocol:

- Model Selection: Benchmark your baseline method (e.g., a classifier using pre-computed ESM-2 embeddings) against PLM-interact.

- Data Setup: Use a standardized cross-species PPI dataset. Train all models exclusively on human PPI data.

- Testing: Evaluate the models on held-out test sets from multiple species (e.g., mouse, fly, worm, yeast, E. coli).

- Metric: Use Area Under the Precision-Recall Curve (AUPR) for evaluation, as it is more informative for imbalanced datasets common in PPI prediction [19].

Table 1: Benchmarking Cross-Species PPI Prediction Performance (AUPR)

| Model | Mouse | Fly | Worm | Yeast | E. coli |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PLM-interact | 0.845 | 0.815 | 0.795 | 0.706 | 0.722 |

| TUnA | 0.825 | 0.735 | 0.735 | 0.641 | 0.655 |

| TT3D | 0.685 | 0.605 | 0.595 | 0.553 | 0.605 |

Performance of PLM-interact versus other state-of-the-art methods when trained on human data and tested on other species. Data adapted from [19].

Issue 2: Poor Transfer Learning Performance on Small, Specialized Datasets

Problem: You are using pLM embeddings as input features for a downstream predictor, but performance is poor on your small, specialized OOD dataset.

Diagnosis and Solutions:

- Diagnosis: The high-dimensional pLM embeddings are overfitting to your small dataset. Furthermore, the chosen embedding compression method may be discarding critical information.

- Solution 1 - Optimize Embedding Compression: As a first and highly effective step, apply mean pooling to compress per-residue embeddings into a single, global protein representation. This method has been shown to consistently outperform alternatives for transfer learning on diverse protein sequences [20].

- Solution 2 - Right-Size Your pLM: Do not default to the largest available pLM. For smaller datasets, a medium-sized model (e.g., 100M to 1B parameters) often provides the best performance-to-efficiency ratio. Using a model like ESM-2 650M with mean-pooled embeddings is a robust and practical starting point [20].

Table 2: pLM Selection Guide for Transfer Learning

| Model Size Category | Example Models | Best For | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Small (<100M params) | ESM-2 8M, 35M | Very small datasets (<100 samples), quick prototyping | Fastest inference, lowest resource use, lower overall accuracy |

| Medium (100M-1B params) | ESM-2 650M, ESM C 600M | Realistic, limited-size datasets, OOD tasks | Optimal balance of performance and efficiency |

| Large (>1B params) | ESM-2 15B, ESM C 6B | Very large datasets, maximum accuracy when data is abundant | High computational cost, potential overfitting on small datasets |

Issue 3: Evaluating Generated or Designed Protein Sequences

Problem: Your pLM has generated thousands of novel protein sequences, and you need to identify the few most promising candidates for laboratory validation.

Diagnosis and Solutions:

- Diagnosis: Relying solely on the pLM's internal scores (like pseudo-likelihood) is insufficient, as they are no guarantee of real-world function or correct folding.

- Solution - Implement a Multi-Stage Evaluation Funnel:

- Sequence-Based Filtering: Apply universal sanity checks to filter out clearly non-viable sequences. This includes checking for the presence of a start codon (M), eliminating sequences with unnatural short repeats, and filtering by length. Use HMMer to ensure the sequence has coverage with the target protein family [21].

- Structure-Based Ranking: For the remaining candidates, predict their 3D structures using a tool like AlphaFold2 or ESMFold.

- Use the TM-score to compare the predicted structure to a known reference structure. A TM-score > 0.5 suggests a similar global fold, while > 0.8 indicates a highly similar fold [22].

- Annotate the secondary structure with DSSP to ensure the conservation of key structural elements like alpha-helices and beta-sheets [21].

- Note: Do not rely on pLDDT alone as a proxy for function, as high confidence can be uncorrelated with functional activity [21].

The following workflow diagram illustrates this evaluation process:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for OOD Protein Analysis

| Tool Name | Type / Category | Primary Function in OOD Context |

|---|---|---|

| ESM-2 & ESM C | Protein Language Model (pLM) | Provides foundational sequence representations and embeddings. Medium-sized versions (650M/600M) are recommended for OOD tasks with limited data [20]. |

| PLM-interact | Fine-tuned PPI Predictor | Predicts protein-protein interactions by jointly encoding pairs, significantly improving cross-species (OOD) generalization compared to single-sequence methods [19]. |

| TM-Vec | Structural Similarity Search | Enables fast, scalable search for structurally similar proteins directly from sequence, bypassing the limitations of sequence-based homology in OOD scenarios [22]. |

| AlphaFold2 / ESMFold | Structure Prediction | Predicts 3D protein structures from sequence. Critical for evaluating whether OOD or generated sequences adopt the intended fold [21]. |

| DeepBLAST | Structural Alignment | Produces structural alignments from sequence pairs, performing similarly to structure-based methods for remote homologs [22]. |

| HMMer | Sequence Homology Search | Used for profile-based sequence search and alignment, providing a standard for checking generated sequence similarity to a protein family [21]. |

| PredictProtein | Meta-Service | Provides a wide array of predictions (secondary structure, solvent accessibility, disordered regions, etc.) useful for initial sequence annotation [23]. |

| 19,20-Epoxycytochalasin C | 19,20-Epoxycytochalasin C, CAS:22144-76-9, MF:C30H37NO6, MW:507.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 5,7,3'-Trihydroxy-4'-Methoxy-8-prenylflavanone | 5,7,3'-Trihydroxy-4'-Methoxy-8-prenylflavanone, CAS:1268140-15-3, MF:C21H22O6, MW:370.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: Why should I consider computer vision-based anomaly detection for my protein research? Computer vision has pioneered powerful unsupervised and self-supervised methods for identifying outliers without needing pre-defined labels for every possible anomaly. These techniques are directly transferable to protein sequences, which can be treated as 1D "images" or through their deep learning-derived embeddings. This paradigm is ideal for finding novel or out-of-distribution protein functions that are rare or poorly understood, as it learns the distribution of "normal" sequences to highlight unusual examples [24].

FAQ 2: What is the fundamental difference between image-level and pixel-level anomaly detection in this context? The choice depends on the scope of the anomaly you are targeting:

- Sequence-Level (Analogous to Image-Level): Assesses whether an entire protein sequence is normal or anomalous. This is suitable for identifying globally unusual proteins, such as those with a novel function or from a rare phylogenetic family [25] [24].

- Residue-Level (Analogous to Pixel-Level): Pinpoints the exact location of anomalies within a protein sequence. This "anomaly segmentation" is ideal for identifying local unusual regions, such as non-classical binding sites or intrinsically disordered segments that deviate from the norm [25] [24].

FAQ 3: My training data is likely contaminated with some anomalous sequences. Is this framework still applicable? Yes. This is a common challenge in real-world data. Frameworks exist for fully-unsupervised refinement of contaminated training data. These methods work by iteratively refining the training set and the model, exploiting information from the anomalies themselves rather than relying solely on a pure "normal" regime. This approach can often outperform models trained on data assumed to be perfectly clean [26].

FAQ 4: How do I represent protein sequences for these kinds of analyses? Modern approaches move beyond handcrafted features to using deep representations. Protein Language Models (pLMs) like ESM and ProtTrans, which are pre-trained on massive protein sequence databases, provide powerful, information-rich embeddings for each amino acid residue. These embeddings implicitly capture information about structure and function, providing an excellent feature space for subsequent density-based anomaly scoring [24].

Troubleshooting Guide

Issue 1: Poor Distinction Between Normal and Anomalous Proteins

Problem: Your model fails to clearly separate anomalous protein sequences from the normal background.

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Inadequate Feature Representation.

- Solution: Transition from handcrafted features to deep representations. Utilize a pre-trained protein Language Model (pLM) to generate residue-level embeddings, as these capture complex biological semantics [24].

- Cause: Weak Anomaly Scoring Function.

- Solution: Implement a density-based scoring rule. A proven method is to compute the average distance of a protein's embedding (or its segments) to its K-nearest neighbors in the training set of normal proteins. Sequences in low-density regions are likely anomalous [24].

- Cause: Improper Data Preprocessing.

- Solution: Ensure your protein embeddings are standardized. Normalize the data to have a mean of zero and a standard deviation of one to prevent features with large variances from dominating the distance calculations.

Issue 2: Inability to Localize Anomalies Within a Sequence

Problem: Your system detects a protein as anomalous but cannot identify which specific residues contribute to the anomaly.

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Using Only Global Sequence Embeddings.

- Solution: Adopt a segmentation approach. Instead of pooling embeddings for the whole sequence, compute anomaly scores for each residue embedding individually. The residue's score is the average distance to its K-nearest neighbor residues from the normal training set [24].

- Cause: Semantic Gap in Feature Space.

- Solution: For reconstruction-based methods, replace standard skip-connections with non-linear transformation blocks (e.g., Chain of Convolutional Blocks). This helps bridge the semantic gap between encoder and decoder features, leading to more precise local reconstruction errors and better anomaly localization [27].

Issue 3: Model Fails to Generalize to Novel Anomalies

Problem: The model performs well on known anomaly types but misses truly novel, unexpected protein families.

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Over-reliance on Supervised Learning.

- Solution: Shift to an unsupervised or self-supervised paradigm. Since novel anomalies are by definition unknown and unlabeled, supervised models will struggle. Techniques like one-class classification or self-supervised learning (e.g., training a model to predict whether a sequence has been altered) learn the distribution of normal data and can flag any significant deviation [25] [28].

- Cause: Training Data is Not Representative of "Normality".

- Solution: Critically review and curate your training set. The model's performance is bounded by the quality and breadth of its "normal" training data. Ensure this set is as comprehensive and contamination-free as possible for the "in-distribution" concept you wish to model [26].

Experimental Protocols & Data

Protocol 1: Whole Protein Anomaly Detection using Density Estimation

This protocol is designed to identify entire protein sequences that are anomalous [24].

1. Feature Extraction:

- Input: A set of protein sequences (amino acid strings).

- Processing: Pass each sequence through a pre-trained protein Language Model (pLM) such as ESM or ProtTrans.

- Output: For each protein, obtain a sequence of vector embeddings, one for each amino acid residue.

2. Protein Representation:

- Method: Generate a single embedding for the whole protein by performing average pooling (calculating the mean) across all of its residue embeddings.

3. Density Estimation and Scoring:

- Training: Using a training set of "normal" proteins, build a reference database of their pooled embeddings.

- Inference: For a test protein, compute its anomaly score as the average Euclidean distance from its pooled embedding to its K-nearest neighbors in the "normal" training database.

- Interpretation: A high score indicates the protein resides in a low-density region of the normal feature space and is likely anomalous.

Protocol 2: Residue-Level Anomaly Segmentation

This protocol pinpoints anomalous regions within a protein sequence [24].

1. Feature Extraction:

- Identical to Step 1 of Protocol 1.

2. Residue-Level Scoring:

- Training: Create a reference database of all individual residue embeddings from all proteins in the "normal" training set.

- Inference: For each residue in a test protein, compute its anomaly score as the average Euclidean distance to its K-nearest neighbor residue embeddings from the normal training database.

3. Anomaly Mapping:

- Output: Plot the anomaly score for each residue position along the protein sequence. Peaks in this plot indicate locally anomalous regions.

The following table summarizes standard metrics used to evaluate anomaly detection systems, as applied in computer vision and related fields [29].

Table 1: Standard Performance Metrics for Anomaly Detection Systems

| Metric | Formula | Interpretation in Protein Research Context |

|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | (TP + TN) / (TP + TN + FP + FN) | Overall ability to correctly classify a protein/region as normal or anomalous. |

| Precision | TP / (TP + FP) | When the model flags an anomaly, the probability that it is a true positive (e.g., a genuinely novel function). |

| Recall | TP / (TP + FN) | The model's ability to find all true anomalies in the dataset. |

| F1-Score | 2 * (Precision * Recall) / (Precision + Recall) | The harmonic mean of Precision and Recall, providing a single balanced metric. |

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the core workflow for deep feature-based protein anomaly detection, integrating both sequence-level and residue-level pathways.

The Scientist's Toolkit

This table details key computational reagents and resources essential for implementing the described anomaly detection framework.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Protein Anomaly Detection

| Research Reagent | Function / Purpose | Example Tools / Libraries |

|---|---|---|

| Protein Language Models (pLMs) | Generates deep, contextual embeddings for amino acid sequences, providing a powerful feature representation for downstream tasks. | ESM, ProtTrans, ProteinBERT [24] |

| Anomaly Detection Algorithms | Provides implementations of core algorithms for density estimation, one-class classification, and clustering. | Scikit-learn (e.g., K-NN, One-Class SVM), PyOD [28] [24] |

| Deep Learning Frameworks | Offers the flexible infrastructure for building, training, and evaluating custom deep learning models, including autoencoders and adversarial networks. | TensorFlow, PyTorch [29] [27] |

| Molecular Dynamics Software | Generates simulation trajectories that can be analyzed using anomaly detection to identify important features and state transitions. | GROMACS, AMBER, NAMD [30] |

| Dimension Reduction Techniques | Helps visualize and interpret high-dimensional protein embeddings by projecting them into 2D or 3D space. | PCA, t-SNE, UMAP [30] |

| N-(3-aminopropyl)acetamide | N-(3-aminopropyl)acetamide, CAS:4078-13-1, MF:C5H12N2O, MW:116.16 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| lucifer yellow ch dipotassium salt | lucifer yellow ch dipotassium salt, CAS:71206-95-6, MF:C13H9K2N5O9S2, MW:521.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Advanced Frameworks and Techniques for OOD Protein Analysis

Leveraging Protein Language Models (pLMs) for Deep Feature Extraction

Troubleshooting Guides

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: My pLM embeddings are high-dimensional and computationally expensive for downstream tasks. What is the most effective compression method?

A1: For most transfer learning applications, mean pooling (averaging embeddings across all amino acid positions) is the most effective and reliable compression method. Systematic evaluations show that mean pooling consistently outperforms other techniques like max pooling, inverse Discrete Cosine Transform (iDCT), and PCA, especially when the input protein sequences are widely diverged. For diverse protein sequence tasks, mean pooling can improve the variance explained (R²) in predictions by 20 to 80 percentage points compared to alternatives [20].

Q2: Does a larger pLM model always lead to better performance for my specific predictive task?

A2: No, larger models do not automatically guarantee better performance, particularly when your dataset is limited. Medium-sized models (approximately 100 million to 1 billion parameters), such as ESM-2 650M and ESM C 600M, often demonstrate performance nearly matching that of much larger models (e.g., ESM-2 15B) while being far more computationally efficient. You should select a model size based on your available data; larger models require larger datasets to unlock their full potential [20].

Q3: How can I safely design new protein sequences without generating non-functional, out-of-distribution (OOD) variants?

A3: To avoid the OOD problem where a proxy model overestimates the functionality of sequences far from your training data, use the Mean Deviation Tree-structured Parzen Estimator (MD-TPE) method. This approach incorporates predictive uncertainty from a Gaussian Process (GP) model as a penalty term, guiding the search toward reliable regions near your training data. The objective function is MD = Ïμ(x) - σ(x), where μ(x) is the predicted property and σ(x) is the model's uncertainty. Setting the risk tolerance Ï < 1 promotes safer exploration [31].

Q4: What are the best practices for setting up a transfer learning pipeline to predict protein properties from sequences?

A4: A robust pipeline involves several key stages [20]:

- Sequence Embedding: Use a pre-trained pLM (e.g., from the ESM or ProtTrans families) to convert your protein sequences into a high-dimensional embedding matrix.

- Embedding Compression: Apply mean pooling to compress the per-residue embeddings into a single, informative vector per protein.

- Model Training: Use the compressed embeddings as input features to train a supervised machine learning model (e.g., LassoCV) to predict your target property.

- Evaluation: Rigorously evaluate the trained model on a held-out test set to determine its predictive performance.

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Problem: Poor predictive performance on downstream tasks.

- Potential Cause 1: Suboptimal embedding compression.

- Solution: Implement mean pooling as your primary compression method and compare its performance against other techniques on a validation set [20].

- Potential Cause 2: Mismatch between model size and dataset size.

- Solution: If you have a small dataset, switch from a very large model (e.g., >1B parameters) to a medium-sized model (e.g., ESM-2 650M) [20].

Problem: Proxy model for protein design suggests sequences that are not expressed or functional.

- Potential Cause: The model is exploring out-of-distribution (OOD) regions of sequence space where its predictions are unreliable.

- Solution: Adopt the MD-TPE framework for sequence optimization. This penalizes exploration in high-uncertainty regions, keeping the search near known functional sequences [31].

Experimental Protocols & Data

Detailed Methodology: Safe Model-Based Optimization with MD-TPE

This protocol is designed for optimizing protein sequences (e.g., for higher brightness or binding affinity) while minimizing the risk of generating non-functional OOD variants [31].

Dataset Preparation:

- Compile a static dataset

D = {(x_i, y_i)}of protein sequences (x_i) and their measured properties (y_i). - Preprocess sequences as required by your chosen pLM.

- Compile a static dataset

Feature Extraction:

- Generate numerical embeddings for all sequences in the dataset using a pLM.

- Compress the embeddings using mean pooling to create a fixed-length feature vector for each sequence [20].

Proxy Model Training:

- Train a Gaussian Process (GP) regression model using the compressed embeddings as inputs (

x) and the target properties as outputs (y). The GP model will learn to predict both the meanμ(x)and uncertaintyσ(x)for any new sequence.

- Train a Gaussian Process (GP) regression model using the compressed embeddings as inputs (

Sequence Optimization with MD-TPE:

- Define the Mean Deviation (MD) objective function:

MD = Ïμ(x) - σ(x). - Set the risk tolerance parameter

Ïbased on desired exploration safety (Ï < 1for safer search). - Use the Tree-structured Parzen Estimator (TPE) to propose new sequence candidates

xthat maximize the MD objective function.

- Define the Mean Deviation (MD) objective function:

Validation:

- Select top-ranking candidate sequences proposed by MD-TPE.

- Validate their functionality through wet-lab experiments.

Performance Data

Table 1: Comparison of Embedding Compression Methods on Different Data Types. Performance is measured by variance explained (R²) on a hold-out test set. [20]

| Compression Method | Deep Mutational Scanning (DMS) Data | Diverse Protein Sequence Data |

|---|---|---|

| Mean Pooling | Superior (Average R² increase of 5-20 pp) | Strictly Superior (Average R² increase of 20-80 pp) |

| Max Pooling | Competitive on some datasets | Outperformed by Mean Pooling |

| iDCT | Competitive on some datasets | Outperformed by Mean Pooling |

| PCA | Competitive on some datasets | Outperformed by Mean Pooling |

Table 2: Practical Performance and Resource Guide for Select Protein Language Models. [20]

| Model | Parameter Size | Recommended Use Case | Performance Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| ESM-2 8M | 8 Million | Small-scale prototyping, educational use | Baseline performance |

| ESM-2 150M | 150 Million | Medium-scale tasks with limited data | Good balance of speed and accuracy |

| ESM-2 650M / ESM C 600M | ~650 Million | Ideal for most academic research | Near-state-of-the-art, efficient |

| ESM-2 15B / ESM C 6B | 6-15 Billion | Large-scale projects with vast data | Top-tier performance, high resource cost |

Workflow Visualizations

MD-TPE Safe Optimization Workflow

pLM Feature Extraction Pipeline

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for pLM-Based Feature Extraction.

| Item / Resource | Type | Function / Application | Key Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| ESM-2 Model Family | Pre-trained pLM | Foundational model for generating protein sequence embeddings; available in multiple sizes [20]. | ESM-2 8M, 650M, 15B |

| ESM C (ESM-Cambrian) | Pre-trained pLM | A high-performance model series; medium-sized variants offer an optimal efficiency-performance balance [20]. | ESM C 300M, 600M, 6B |

| ProtTrans Model Family | Pre-trained pLM | Alternative family of powerful pLMs for generating protein representations [20]. | ProtT5, ProtBERT |

| Deep Mutational Scanning (DMS) Data | Benchmark Dataset | Used to train and evaluate models on predicting effects of single or few point mutations [20]. | 41 DMS datasets covering stability, activity, etc. |

| PISCES Database | Benchmark Dataset | Provides diverse protein sequences for evaluating global property predictions [20]. | Used for predicting physicochemical properties |

| Gaussian Process (GP) Model | Proxy Model | Used in optimization frameworks; provides predictive mean and uncertainty estimates [31]. | Core component of MD-TPE |

| Tree-structured Parzen Estimator (TPE) | Optimization Algorithm | Bayesian optimization method ideal for categorical spaces like protein sequences [31]. | Core component of MD-TPE |

| Salvianolic acid H | Salvianolic acid H, MF:C27H22O12, MW:538.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| (Rac)-BRD0705 | (Rac)-BRD0705, MF:C20H23N3O, MW:321.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Density-Based Anomaly Scoring with Nearest Neighbors Approaches

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the core principle behind density-based anomaly scoring?

Density-based anomaly scoring identifies outliers by comparing the local density of a data point to the density of its nearest neighbors. Unlike global methods, it doesn't just ask "Is this point far from the rest?" but instead asks, "Is this point in a sparse region compared to its immediate neighbors?" [32]. This makes it exceptionally effective for datasets where different regions have different densities, or where anomalies might hide in otherwise dense clusters [32].

Q2: How does the Local Outlier Factor (LOF) algorithm work?

The Local Outlier Factor (LOF) is a key density-based algorithm. It calculates a score (the LOF) for each data point by comparing its local density with the densities of its k-nearest neighbors [32]. A score approximately equal to 1 indicates that the point has a density similar to its neighbors. A score significantly less than 1 suggests a higher density (a potential inlier), while a score much greater than 1 indicates a point with a density lower than its neighbors, marking it as a potential anomaly [32].

Q3: What are the advantages of using K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN) for anomaly detection in protein sequence analysis?

KNN is a versatile algorithm that can be used for unsupervised anomaly detection. It computes an outlier score based on the distances between a data point and its k-nearest neighbors [33]. A point that is distant from its neighbors will have a high anomaly score. This distance-based approach is useful for tasks like identifying outlier protein sequences whose functional or structural characteristics differ from the norm, which is crucial for ensuring the reliability of downstream analyses like phylogenetic studies or function prediction [34].

Q4: In the context of protein sequences, what defines an "out-of-distribution" (OOD) sample?

In protein engineering and bioinformatics, an out-of-distribution sample refers to a protein sequence that is far from the training data distribution [6]. This can include:

- Non-homologous sequences included by accident [34].

- Sequences with mistranslated regions due to sequencing errors [34].

- Highly divergent homologous sequences that are very hard to align and where the proxy model cannot reliably predict their properties [6]. Exploring these OOD regions with standard models often leads to pathological behavior, as the models may yield excessively good values for sequences that, in reality, may not be expressed or functional [6].

Q5: What is a common troubleshooting issue when using DBSCAN for anomaly detection, and how can it be resolved?

A common issue is the sensitivity to parameter selection, specifically the Epsilon (eps) and MinPoints parameters. Poor parameter choices can reduce outlier detection accuracy by up to 40% [35].

Solution: Use the k-distance graph (or elbow method) to choose eps. Plot the distance to the k-nearest neighbor for all points, sorted in descending order. The ideal eps value is often found at the "elbow" of this graph—the point where a sharp change in the curve occurs [35].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Issue 1: Poor Performance on Data with Varying Densities

- Problem: Standard algorithms like DBSCAN assume consistent density across clusters. Performance degrades when your protein sequence dataset has natural clusters with different densities.

- Solution: Employ enhanced algorithms like OPTICS or HDBSCAN [35]. These methods handle varying densities more effectively. HDBSCAN, in particular, requires only a minimum cluster size parameter and excels at noise handling, making it a robust choice for complex biological data [35].

Issue 2: Proxy Model Overestimates the Quality of Out-of-Distribution Protein Sequences

- Problem: In offline Model-Based Optimization for protein design, a proxy model trained on limited data may assign unrealistically high scores to sequences far from the training distribution (OOD sequences), which often lose function [6].

- Solution: Implement a safe optimization approach that penalizes exploration in OOD regions. One method is to use a modified objective function, such as the Mean Deviation (MD), which incorporates the predictive uncertainty of a model (e.g., a Gaussian Process) as a penalty term. This guides the search toward regions near the training data where the model's predictions are more reliable [6].

Issue 3: High Computational Complexity with Large Sequence Datasets

- Problem: Computing a full pairwise distance matrix for a large set of protein sequences has a time and memory complexity of O(N²), which becomes prohibitive [34].

- Solution: Leverage algorithms that use dimensionality reduction or approximation. The mBed algorithm can reduce the complexity to O(N log N) by randomly selecting a subset of seed sequences and computing a reduced distance matrix, making large-scale analysis feasible [34].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 1: Essential computational tools and resources for density-based anomaly detection in protein sequences.

| Item | Function / Description |

|---|---|

| DBSCAN | A foundational density-based clustering algorithm that groups points into dense regions and directly flags isolated points as noise (outliers) based on eps and min_samples parameters [35]. |

| LOF (Local Outlier Factor) | An algorithm specifically designed for anomaly detection that assigns an outlier score based on the relative density of a point compared to its neighbors [32]. |

| HDBSCAN | An advanced density-based algorithm that creates a hierarchy of clusters and requires minimal parameter tuning, offering strong noise handling for datasets with varying densities [35]. |

| OD-seq | A specialized software package designed to automatically detect outlier sequences in multiple sequence alignments by identifying sequences with anomalous average distances to the rest of the dataset [34]. |

| Gaussian Process (GP) Model | A probabilistic model that outputs both a predictive mean and its associated uncertainty (deviation). It can be used as a proxy model to guide safe exploration in protein sequence space by avoiding high-uncertainty (OOD) regions [6]. |

| mBed Algorithm | A method used to reduce the computational complexity of analyzing large distance matrices from O(N²) to O(N log N), making large-scale sequence alignment analysis practical [34]. |

| Surprisal / Log Score | A measure of anomaly defined as ( si = -\log f(\mathbf{y}i) ), where ( f ) is a probability density function. It quantifies how "surprising" an observation is under a given distribution [36]. |

| Trk-IN-30 | Trk-IN-30, MF:C24H21N5O3, MW:427.5 g/mol |

| Branosotine | Branosotine, CAS:2412849-26-2, MF:C26H26FN7O, MW:471.5 g/mol |

Experimental Protocols & Data Presentation

Protocol 1: Detecting Outliers in a Multiple Sequence Alignment using OD-seq

This protocol is based on the methodology described in the OD-seq software publication [34].

- Input Preparation: Provide your multiple sequence alignment (MSA) file in a supported format (e.g., FASTA, Clustal).

- Distance Matrix Calculation: OD-seq computes a pairwise distance matrix using a gap-based metric. You can typically choose from:

- Outlier Identification: The algorithm calculates the average distance of each sequence to all others. It then flags sequences with anomalously high average distances using statistical methods like:

- Output: A list of sequences identified as outliers for further investigation or removal.

Table 2: Quantitative performance of OD-seq on seeded Pfam family test cases [34].

| Metric | Performance |

|---|---|

| Input Type | Multiple Sequence Alignment (MSA) |

| Sensitivity & Specificity | Very High |

| Analysis Time | Few seconds for alignments of a few thousand sequences |

| Computational Complexity | O(N log N) (using mBed) |

Protocol 2: Safe Exploration for Protein Sequence Optimization using MD-TPE

This protocol outlines the safe optimization approach using the Mean Deviation Tree-structured Parzen Estimator (MD-TPE) to avoid non-functional, out-of-distribution sequences [6].

- Dataset Creation: Compile a static dataset

Dof protein sequences (e.g., GFP variants) with their associated measured properties (e.g., brightness). - Model Training:

- Embed the protein sequences into numerical vectors using a protein language model (PLM).

- Train a Gaussian Process (GP) model as a proxy function on this embedded dataset. This model will learn to predict the property of interest and, crucially, its own uncertainty.

- Define the Safe Objective Function: Instead of optimizing the GP's predicted value alone, optimize the Mean Deviation (MD) objective: ( \text{MD}(\mathbf{x}) = \mu(\mathbf{x}) - \lambda \cdot \sigma(\mathbf{x}) ) where ( \mu(\mathbf{x}) ) is the GP's predictive mean, ( \sigma(\mathbf{x}) ) is its predictive deviation (uncertainty), and ( \lambda ) is a risk tolerance parameter [6].

- Sequence Optimization with MD-TPE: Use the TPE algorithm to sample new sequences, but with MD as the objective. This penalizes sequences in high-uncertainty (OOD) regions, biasing the search toward the vicinity of the training data where the GP model is reliable.

- Validation: Select top candidate sequences identified by MD-TPE for wet-lab experimental validation.

Table 3: Comparison of TPE vs. MD-TPE performance on a GFP brightness task [6].

| Metric | Conventional TPE | MD-TPE (Proposed Method) |

|---|---|---|

| Exploration Behavior | Explored high-uncertainty (OOD) regions | Stayed in reliable, low-uncertainty regions |

| Mutations from Parent | Higher number of mutations | Fewer mutations (safer optimization) |

| GP Deviation of Top Sequences | Larger | Smaller |

| Result | Some sequences non-functional | Successfully identified brighter, expressed mutants |

Workflow and Relationship Visualizations

Diagram 1: LOF Algorithm Workflow

Diagram 2: Safe Protein Sequence Optimization

Diagram 3: Algorithm Selection Guide

Whole-Sequence vs. Residue-Level Anomaly Detection Strategies

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the core difference between whole-sequence and residue-level anomaly detection strategies?

Whole-sequence strategies analyze a protein's entire amino acid sequence to identify outliers that deviate significantly from a background distribution of normal sequences [37]. In contrast, residue-level strategies identify individual amino acids or small groups of residues within a single sequence whose behavior or correlation with other residues is unusual, often by comparing multidimensional time series from different states [30].

FAQ 2: When should I prioritize a residue-level approach for analyzing protein dynamics?

A residue-level approach is particularly powerful when your goal is to identify specific residues responsible for state transitions (e.g., open/closed states, holo/apo states) or allosteric communication [30]. This method is ideal for identifying a small number of key "order parameters" or "features" from MD simulation trajectories, which can then serve as informative collective variables for enhanced sampling methods or for interpreting the mechanistic basis of a biological phenomenon [30].

FAQ 3: My experimental dataset of labeled protein functions is very small. Which strategy is more effective?

For small experimental training sets, protein-specific models that can leverage local biophysical signals tend to outperform general whole-sequence models. For instance, the METL-Local framework, which is pretrained on biophysical simulation data for a specific protein of interest, has demonstrated a strong ability to generalize when fine-tuned on as few as 64 sequence-function examples [37].

FAQ 4: How can network-based anomaly detection reveal tissue-specific protein functions?

Network-based methods like the Weighted Graph Anomalous Node Detection (WGAND) algorithm treat proteins as nodes in a Protein-Protein Interaction (PPI) network. They identify anomalous nodes whose edge weights (likelihood of interaction) significantly deviate from the expected norm in a specific tissue [38]. These anomalous proteins are highly enriched for key tissue-specific biological processes and disease associations, such as neuron signaling in the brain or spermatogenesis in the testis [38].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Poor Generalization on Out-of-Distribution Protein Sequences

- Symptoms: Your anomaly detection or property prediction model performs well on proteins similar to its training data but fails on proteins with different folds or low sequence similarity.

- Solution A: Leverage Biophysics-Based Pretraining

- Protocol: Implement a framework like METL. Pretrain a transformer model on synthetic data generated from molecular simulations (e.g., using Rosetta) to learn fundamental biophysical relationships between sequence, structure, and energetics. Subsequently, fine-tune this pretrained model on your small, targeted experimental dataset [37].

- Rationale: This grounds the model in biophysical principles, providing a strong inductive bias that helps it reason about proteins beyond the evolutionary record.

- Solution B: Employ a Residue-Level Sparse Correlation Analysis

- Protocol:

- Perform MD simulations from the initial structures of different protein states.

- Choose a set of input coordinates (e.g., residue-residue distances).

- For the trajectory of each state, use the graphical lasso to estimate a sparse precision matrix (inverse covariance matrix) that reveals the essential correlation relationships between residues.

- Identify anomalous residues by comparing the two sparse correlation structures from the different states [30].

- Rationale: This method focuses on internal dynamics and state-dependent correlations, making it less sensitive to overall sequence divergence.

- Protocol:

Problem 2: Identifying Biologically Meaningful Anomalies from Weighted PPI Networks

- Symptoms: Standard network metrics fail to highlight proteins with known tissue-specific functions or disease associations.

- Solution: Apply the WGAND Algorithm

- Protocol:

- Input: A weighted PPI network for your tissue of interest, where edge weights reflect interaction likelihoods.

- Step 1 - Node Embedding: Generate numerical features (embeddings) for each protein node using a method like RandNE [38].

- Step 2 - Edge Weight Estimation: Train a regression model (e.g., LightGBM or Random Forest) to predict the weight of an edge based on the features of the two nodes it connects [38].

- Step 3 - Meta-feature Construction: For each node, calculate meta-features based on the error between its actual and predicted edge weights (e.g., mean error, standard deviation of error) [38].

- Step 4 - Anomaly Scoring: Use these meta-features to compute a final anomaly score for each node. High-scoring nodes are your anomalies.

- Rationale: Proteins involved in critical tissue-specific roles often have interaction patterns that deviate from the global network norm, which WGAND is designed to detect [38].

- Protocol:

Problem 3: Detecting Subtle State-Transition Features in MD Trajectories

- Symptoms: You have MD trajectories of a protein in different states (e.g., ligand-bound vs. unbound), but standard dimension reduction techniques like PCA do not yield a clear signal for the state transition.

- Solution: Anomaly Detection via Sparse Structure Learning

- Protocol:

- Data Preparation: From your MD trajectories, extract a multivariate time series of structural elements, such as distances between residue pairs. Standardize the data for each element [30].

- Sparse Model Learning: For the trajectory of each state, model the probability distribution of the elements as a multidimensional Gaussian with a sparse precision matrix. Use maximum a posteriori (MAP) estimation with a Laplacian prior to enforce sparsity and learn the essential correlation network for each state [30].

- Anomaly Identification: Compare the two learned sparse precision matrices. Residues or features whose correlation relationships differ most markedly between the two states are identified as highly anomalous and are likely key to the state transition [30].

- Rationale: This method filters out spurious correlations and pinpoints the specific subset of residues whose coordinated behavior changes between functional states.

- Protocol: