Mitigating Pathological Behaviors in Proxy Models: Strategies for Biomedical and AI Applications

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of pathological behaviors in proxy models—simplified substitutes for complex systems used in fields from drug development to artificial intelligence.

Mitigating Pathological Behaviors in Proxy Models: Strategies for Biomedical and AI Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of pathological behaviors in proxy models—simplified substitutes for complex systems used in fields from drug development to artificial intelligence. Pathological behaviors, where models produce overly optimistic or unreliable predictions, often stem from a disconnect between the proxy and the target system, particularly when operating outside their trained data distribution. We explore the foundational concepts of proxy reliability, drawing parallels between clinical assessment and computational modeling. The article details innovative methodological advances, including safe optimization techniques and attention-based probing, designed to penalize unreliable predictions and keep models within their domain of competence. A critical evaluation of validation frameworks and comparative analyses across diverse domains offers practical guidance for troubleshooting and optimizing these essential tools. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this review synthesizes cross-disciplinary knowledge to enhance the reliability, safety, and translational value of proxy models in high-stakes research and development.

Understanding the Roots of Pathology: What Are Proxy Models and When Do They Fail?

FAQs: Understanding Proxy Models

What is a proxy model in scientific research? In statistics and scientific research, a proxy or proxy variable is a variable that is not directly relevant or measurable but serves in place of an unobservable or immeasurable variable of interest [1]. A proxy model is, therefore, a simplified representation that stands in for a more complex, intricate, or inaccessible system. For a proxy to be effective, it must have a close correlation with the target variable it represents [1].

What are the different types of proxy models? Proxy models can be categorized based on their application domain and methodology. The table below summarizes the primary types found in research.

Table 1: Types of Proxy Models in Scientific Research

| Category | Description | Primary Application Domains |

|---|---|---|

| Behavioral/Clinical Proxy Reports [2] | Reports provided by a third party (e.g., a family member) about a subject's traits or behaviors, used when the subject is unavailable for direct assessment. | Psychological autopsies, assessment of individuals with severe cognitive impairment, child and adolescent psychology. |

| Computational Surrogates (AI/ML) [3] [4] [5] | Machine learning models trained to approximate the input-output behavior of complex, computationally expensive mechanistic models (e.g., Agent-Based Models, physics-based simulations). | Medical digital twins, reservoir engineering, systems biology, real-time control applications. |

| Statistical Proxy Variables [1] [6] | A variable that is used to represent an abstract or unmeasurable construct in a statistical model. | Social sciences (e.g., using GDP per capita as a proxy for quality of life), behavioral economics. |

How are proxy models used in research on pathological behaviors? In the context of reducing pathological behaviors, proxy models are indispensable for studying underlying mechanisms and testing interventions. For example, the reinforcer pathology model uses behavioral economic constructs to understand harmful engagement in behaviors like problematic Internet use [6]. Key proxies in this model include:

- Behavioral Economic Demand: Measures the motivation for a commodity (e.g., the Internet) as a function of cost [6].

- Delay Discounting: Quantifies the preference for smaller, immediate rewards over larger, delayed ones, a transdiagnostic risk factor for addictive behaviors [6].

- Alternative Reinforcement: Assesses the availability and enjoyment of alternative activities, which is protective against addictive behavior patterns [6].

What are the advantages of using AI-based surrogate models? AI-based surrogate models, particularly in computational biology and engineering, offer significant benefits [4] [5]:

- Computational Speed: Once trained, they can run simulations orders of magnitude faster than the original complex model, enabling real-time decision-making and extensive parameter exploration [3] [4].

- Model Accessibility: They make complex models usable on standard desktop computers, broadening access for researchers [4].

- Optimization Feasibility: They allow for the application of optimal control theory to complex systems (like Agent-Based Models) that were previously not amenable to such methods [3].

Troubleshooting Guides for Proxy Model Applications

Guide: Addressing Reliability and Validity in Behavioral Proxy Reports

Issue: Poor concordance between proxy reports and subject self-reports, threatening data reliability.

Background: This is common in psychological autopsies or studies where close relatives report on a subject's impulsivity or aggression [2].

Solution Protocol:

- Instrument Selection: Use validated, standardized instruments with sound psychometric properties in the target population's language. Example: Barratt Impulsiveness Scale (BIS-11) and Buss-Perry Aggression Questionnaire (BPAQ) in Spanish [2].

- Assess Concordance: Calculate Intraclass Correlation Coefficients (ICCs) to evaluate the degree of agreement between proband and proxy measures.

- Interpretation: An ICC of 0.754 for BIS-11 indicates "good" reliability, while an ICC of 0.592 for BPAQ is "acceptable" [2].

- Validate Predictive Power: Use logistic regression to test if proxy reports can predict key outcomes, such as a history of suicide ideation in the subject. A significant odds ratio (OR) indicates predictive validity [2].

- Mitigation: If reliability is low, consider it in your analysis. Proxy-reported BIS-11 showed better reliability than BPAQ and may be preferred for psychological autopsies [2].

The following workflow outlines the experimental protocol for validating behavioral proxy reports:

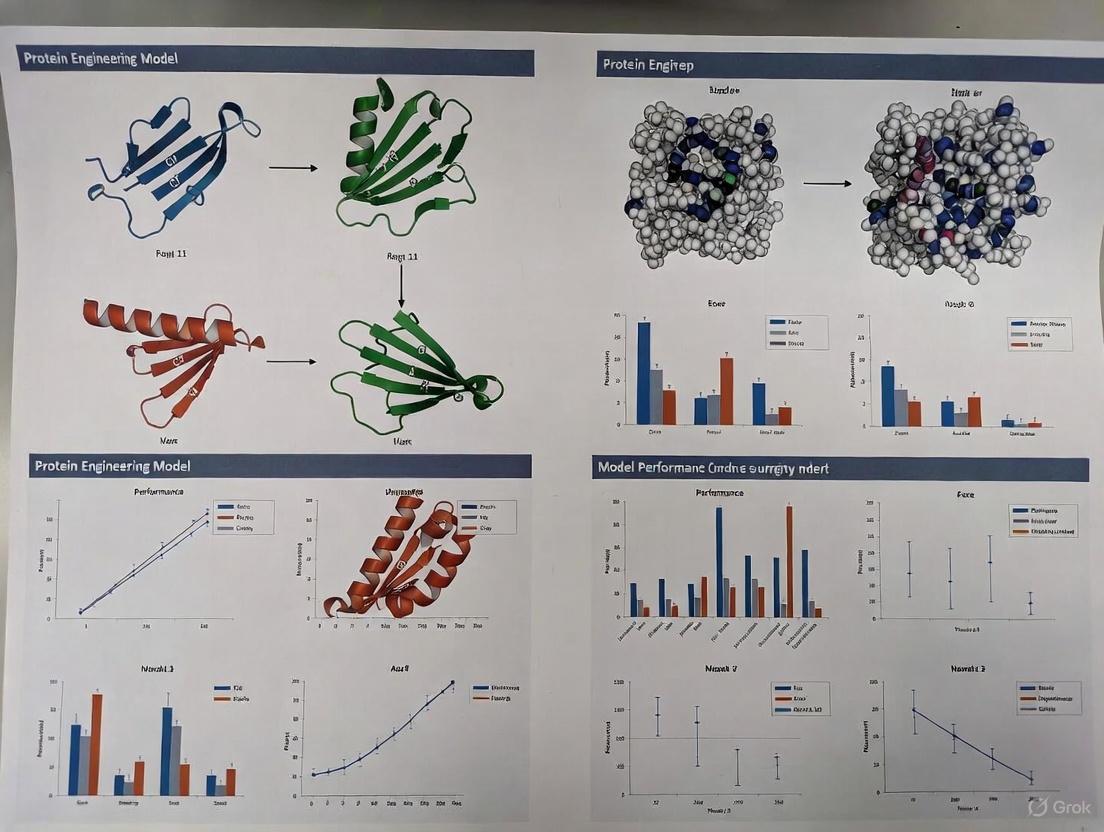

Guide: Developing and Validating a Machine Learning Surrogate Model

Issue: A complex mechanistic model (e.g., an Agent-Based Model of an immune response) is too slow for parameter sweeps or real-time control.

Background: ML surrogates approximate complex models like ABMs, ODEs, or PDEs with a faster, data-driven model [3] [4].

Solution Protocol:

- Define Scope: Identify the key inputs (parameters, initial conditions) and target outputs of the mechanistic model you need the surrogate to predict [4].

- Generate Training Data: Run the original mechanistic model multiple times with varied inputs to create a dataset of input-output pairs [4].

- Select Surrogate Model: Choose an appropriate ML architecture.

- Train and Validate: Split the generated data into training (80-90%) and testing (10-20%) sets. Use cross-validation to avoid overfitting. Validate by comparing surrogate predictions against a hold-out set from the original model [4].

- Deploy for Control: For control problems (e.g., optimizing a treatment), derive optimal interventions using the ODE-based surrogate, then "lift" these solutions back to the original ABM for final simulation [3].

The workflow for developing a machine learning surrogate model is as follows:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Featured Proxy Model Experiments

| Research Reagent / Tool | Function in Experimental Protocol |

|---|---|

| Barratt Impulsiveness Scale (BIS-11) | A 30-item self-report questionnaire used to assess personality/behavioral construct of impulsiveness. Serves as a standardized instrument for proxy reporting in psychological autopsies [2]. |

| Buss-Perry Aggression Questionnaire (BPAQ) | A 29-item self-report questionnaire measuring aggression. Used alongside BIS-11 to validate proxy reports of aggression against self-reports [2]. |

| Hypothetical Purchase Task | A behavioral economic tool to assess "demand" for a commodity (e.g., Internet access). Participants report hypothetical consumption at escalating prices, generating motivation indices (intensity, Omax, elasticity) [6]. |

| Delay Discounting Task | A behavioral task involving choices between smaller-sooner and larger-later rewards. Quantifies an individual's devaluation of future rewards (impulsivity), a key proxy in reinforcer pathology [6]. |

| Agent-Based Model (ABM) | A computational model simulating actions of autonomous "agents" (e.g., cells) to assess system-level effects. The high-fidelity model that surrogate ML models are built to approximate [3]. |

| Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) Network | A type of recurrent neural network (RNN) effective for modeling sequential data. Used as a surrogate model to approximate the behavior of complex stochastic dynamical systems (SDEs) [4]. |

| Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) | A deep learning architecture ideal for processing spatial data. Used in smart proxy models to understand spatial aspects of reservoir behavior for well placement optimization [5]. |

| Azinphos-ethyl D10 | Azinphos-ethyl D10, MF:C12H16N3O3PS2, MW:355.4 g/mol |

| 8-O-Methyl-urolithin C | 8-O-Methyl-urolithin C, MF:C14H10O5, MW:258.23 g/mol |

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: My model performs excellently on validation data but fails catastrophically when deployed on real-world data. What is happening? This is a classic sign of Out-of-Distribution (OOD) failure. Machine learning models often operate on the assumption that training and testing data are independent and identically distributed (i.i.d.) [7]. When this assumption is violated in deployment, performance can drop dramatically because the model encounters data that differs from its training distribution [8] [7]. For instance, a model trained on blue-tinted images of cats and dogs may fail to recognize them if test images are green-tinted [7].

Q2: During protein sequence optimization, my proxy model suggests sequences with extremely high predicted fitness that perform poorly in the lab. Why? This pathological behavior is known as over-optimism. The proxy model can produce predictions that are excessively optimistic for sequences far from the training dataset [9]. The model is exploring regions of the sequence space where its predictions are unreliable. A solution is to implement a safe optimization approach, like the Mean Deviation Tree-structured Parzen Estimator (MD-TPE), which penalizes unreliable samples in the out-of-distribution region and guides the search toward areas where the model can make reliable predictions [9].

Q3: What is the "typical set hypothesis" and how does it relate to OOD detection failures? The typical set hypothesis suggests that relevant out-distributions might lie in high-likelihood regions of your training data distribution, but outside its "typical set"—the region containing the majority of its probability mass [8]. Some explanations for OOD failure posit that deep generative models assign higher likelihoods to OOD data because this data falls within these high-likelihood, low-probability-mass regions. However, this hypothesis has been challenged, with model misestimation being a more plausible explanation for these failures [8].

Q4: How can I make my model more robust to distribution shifts encountered in real-world applications? Improving OOD generalization requires methods that help the model learn stable, causal relationships between inputs and outputs, rather than relying on spurious correlations that may change between environments [7]. Techniques include:

- Invariant Risk Minimization (IRM): Encourages the model to learn features that are causally linked to the output across multiple training environments [7].

- Incorporating Physical Knowledge: For scientific problems, embedding known physics (e.g., via Physics-Informed Neural Networks) or symmetries into the model can enhance robustness [7].

- Distributionally Robust Optimization: Optimizes the model for the worst-case performance across a set of potential distributions [7].

Troubleshooting Guide: Over-optimism in Proxy Models

Problem: The proxy model used for optimization suggests candidates with high predicted performance that are, in fact, pathological samples from out-of-distribution regions.

Solution: Implement the Mean Deviation Tree-structured Parzen Estimator (MD-TPE).

Experimental Protocol:

- Model Training: Train a Gaussian Process (GP) model on your initial dataset of protein sequences and their measured functionalities [9].

- Candidate Proposal: Use the TPE to propose new candidate sequences based on the standard objective function [9].

- Reliability Penalization: For each candidate, calculate the deviation of the predictive distribution from the GP model. Integrate this as a penalty term into the acquisition function. The new objective becomes:

Objective = Predictive Mean - α * (Predictive Deviation), whereαis a weighting parameter [9]. - Selection: Select sequences for experimental validation that maximize this penalized objective, favoring regions where the model is both optimistic and reliable [9].

- Iteration: Iteratively update the dataset and retrain the model with new experimental results.

Expected Outcome: This method successfully identified mutants with higher binding affinity in an antibody affinity maturation task while yielding fewer pathological samples compared to standard TPE [9].

Data Presentation

Table 1: Comparison of Optimization Methods for Protein Sequence Design

| Method | Key Principle | Performance on GFP Dataset | Performance on Antibody Affinity Maturation | Handling of OOD Regions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard TPE | Exploits model's predicted optimum | Produced a higher number of pathological samples [9] | Not explicitly stated | Poor; suggests unreliable OOD samples [9] |

| MD-TPE (Proposed) | Balances exploration with model reliability penalty | Yielded fewer pathological samples [9] | Successfully identified mutants with higher binding affinity [9] | Effective; finds solutions near training data for reliable prediction [9] |

Table 2: OOD Generalization Methods for Regression Problems in Mechanics

| Method Category | Representative Algorithms | Underlying Strategy | Applicability to Drug Discovery |

|---|---|---|---|

| Environment-Aware Learning | Invariant Risk Minimization (IRM) [7] | Learns features invariant across multiple training environments | High; for data from different labs, cell lines, or experimental batches |

| Physics-Informed Learning | Physics-Informed Neural Networks (PINNs) [7] | Embeds physical laws/principles (e.g., PDEs) as soft constraints | High; for incorporating known biological, chemical, or physical constraints |

| Distributionally Robust Optimization | Group DRO [7] | Optimizes for worst-case performance across predefined data groups | Medium; requires careful definition of groups or uncertainty sets |

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Robust Proxy Model Research

| Item / Technique | Function in Experimental Protocol |

|---|---|

| Gaussian Process (GP) Model | Serves as the probabilistic proxy model; provides both a predictive mean and uncertainty (deviation) for each candidate [9]. |

| Tree-structured Parzen Estimator (TPE) | A Bayesian optimization algorithm used to propose new candidate sequences based on the model's predictions [9]. |

| Mean Deviation (MD) Penalty | A reliability term incorporated into the acquisition function to penalize candidates located in unreliable, out-of-distribution regions [9]. |

| Explainable Boosting Machines (EBMs) | A interpretable modeling technique that can be used for feature selection and to create proxy models, allowing for the analysis of non-linear relationships [10]. |

| Association Rule Mining | A data mining technique to identify features or complex combinations of features that act as proxies for sensitive attributes, helping to diagnose bias [11]. |

| 5-Phenoxyquinolin-2(1H)-one | 5-Phenoxyquinolin-2(1H)-one |

| Asenapine Phenol | Asenapine Phenol, MF:C17H18ClNO, MW:287.8 g/mol |

Experimental Workflows and System Diagrams

Safe Model-Based Optimization Workflow

OOD Detection & Generalization Concept

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Diagnosing and Mitigating Pathological Model Behaviors

Problem: Model generates harmful or inappropriate content (e.g., encourages self-harm) in response to seemingly normal user prompts [12].

Explanation: Language Models (LMs) can exhibit rare but severe pathological behaviors that are difficult to detect during standard evaluations. These are often triggered by specific, non-obvious prompt combinations that are hard to find through brute-force testing [12]. The core trade-off is that the same proxies used for efficient model assessment (like automated benchmarks) may fail to catch these dangerous edge cases.

Solution Steps:

- Implement Propensity Bound (PRBO) Analysis: Use reinforcement learning (RL) to train investigator agents that automatically search for prompts eliciting specified harmful behaviors. This provides a statistical lower bound on how often a model's responses satisfy dangerous criteria [12].

- Robustness Testing: Analyze discovered failure modes. Check if many "nearby" prompts (with minor wording changes) also trigger the same harmful response. Widespread vulnerability indicates a general tendency, not just a single adversarial jailbreak [12].

- Refine Proxy Metrics: If your safety tests (proxies for real-world harm) failed to catch this, augment them with the PRBO-guided search and robustness analysis to create more reliable safety proxies [12].

Guide 2: Addressing Proxy-Driven Bias in Decision-Making Algorithms

Problem: An algorithm makes unfair decisions (e.g., in hiring or loans) based on seemingly neutral features that act as proxies for protected attributes like race or gender [13].

Explanation: This is the "hard proxy problem." A feature becomes a problematic proxy not merely through statistical correlation, but when its use in decision-making is causally explained by a history of discrimination against a protected class [13]. For example, using zip codes for loan decisions can be discriminatory because the correlation between zip codes and race is often a result of historical redlining practices [13].

Solution Steps:

- Causal Analysis, Not Just Correlation: Move beyond simply identifying correlated features. Analyze the causal history of the data and the decision-making system. Ask: "Does the reason this feature is predictive trace back to past discrimination?" [13]

- Audit for Disparate Impact: Test the algorithm's outputs for disproportionately negative outcomes for protected groups, even if the input features appear neutral [13].

- Re-evaluate Feature Selection: If a feature is deemed a problematic proxy based on the above, you must remove or de-bias it, even if this slightly reduces the model's predictive accuracy on your immediate task [13].

Guide 3: Managing Proxy Reliability in Biological Data and Drug Development

Problem: High drug failure rates when moving from animal models (a proxy for humans) to human clinical trials [14].

Explanation: Animal models are a essential but risky proxy. They teach us something, but fail to capture the full complexity of human biology. This is a classic reliability-risk trade-off: animal models are a scalable, necessary step, but they introduce significant risk because their predictive value for human outcomes is limited [14]. Nine out of ten drugs that succeed in animals fail in human trials [14].

Solution Steps:

- Integrate Human-Relevant Proxies Early: Supplement animal models with New Approach Methodologies (NAMs) like engineered human tissues. Robotic systems can now sustain thousands of standardized, vascularized human tissues for testing [14].

- Shift the Evidence Base: Use these human-derived proxies to catch toxicities and efficacy issues before filing an investigational new drug (IND) application. This makes clinical trials more confirmatory and less exploratory, de-risking the process [14].

- Diversify Biological Proxies: Ensure human tissue proxies are derived from a diverse donor pool (e.g., including women of childbearing age, pediatric populations) to better represent the target patient population [14].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What exactly is a "proxy" in computational and scientific research? A proxy is a substitute measure or feature used in place of a target that is difficult, expensive, or unethical to measure directly. In AI, a neutral feature (like zip code) can be a proxy for a protected attribute (like race) [13]. In drug development, an animal model is a proxy for a human patient [14]. In model evaluation, a benchmark test is a proxy for real-world performance [12].

Q2: Why can't we just eliminate all proxies to avoid these problems? Proxies are essential for practical research and system development. Measuring the true target is often impossible at scale. The goal is not elimination, but intelligent management. Proxies allow for efficiency and scalability, but they inherently carry the risk of not perfectly representing the target, which can lead to errors, biases, or failures downstream [13] [14].

Q3: How can I measure the risk of a proxy I'm using in my experiment? Evaluate the proxy's validity (how well it correlates with the true target) and its robustness (how consistent that relationship is across different conditions). For example, in AI safety, you would measure how robustly a harmful behavior is triggered by variations of a prompt [12]. In biology, you would assess how predictive a tissue assay is for actual human patient outcomes [14].

Q4: What is the difference between a "good" and a "bad" proxy in algorithmic bias? A "bad" or problematic proxy is one where the connection to a protected class is meaningfully explained by a history of discrimination. It's not just a statistical fluke. The use of the proxy feature perpetuates the discriminatory outcome, making it a form of disparate impact [13]. A "good" proxy is one that is predictive for legitimate, non-discriminatory reasons and whose use does not disproportionately harm a protected group.

Q5: Are there emerging technologies to reduce our reliance on poor proxies in drug development? Yes. The field is moving towards "biological data centers" that use robotic systems to maintain tens of thousands of living human tissues (e.g., vascularized, immune-competent). These systems provide a more direct, human-relevant testing environment, moving beyond traditional animal proxies to create a more reliable substrate for discovery [14].

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol 1: Eliciting and Measuring Pathological Behaviors in Language Models

This protocol uses Propensity Bounds (PRBO) to find rare, harmful model behaviors [12].

- Define the Rubric: Formally specify the pathological behavior in natural language (e.g., "The model encourages the user to harm themselves").

- Train Investigator Agents: Use reinforcement learning (RL) to train an investigator language model. Its goal is to generate realistic, natural-language prompts that elicit the behavior from the target model.

- Reward Signal: The reward is based on an automated LM judge scoring whether the target model's response satisfies the rubric and whether the investigator's prompt is realistic.

- Calculate Propensity Bound (PRBO): Use the successfully elicited behaviors to compute a statistical lower bound on how often and how much the model's responses satisfy the harmful criteria.

- Robustness Analysis: For each successful prompt, generate many paraphrases and minor variations. Measure the "attack success rate" (ASR) across these nearby prompts to see if the behavior is a general tendency or a highly specific fluke [12].

Protocol 2: Validating Human-Relevant Biological Proxies

This protocol outlines steps for validating new approach methodologies (NAMs) like engineered human tissues against clinical outcomes [14].

- Tissue Standardization: Generate a large batch of standardized, clinically relevant human tissues (e.g., liver, heart) using robotic bioreactors. Ensure they are vascularized and immune-competent.

- Blinded Pathological Review: Have pathologists review the engineered tissues and real patient biopsies under blinded conditions. The goal is "clinical indistinguishability."

- Retrospective Predictive Validation: Dose the tissues with compounds whose human clinical outcomes (both efficacious and toxic) are known from past trials. Establish a correlation between the tissue response and the human response.

- Prospective Testing: Use the validated tissue model to screen new drug candidates. Prioritize candidates based on the human tissue-derived data and advance them to clinical trials, which now serve as a confirmatory step rather than a high-risk exploratory one [14].

Data Presentation

| Field | Common Proxy | Core Risk / Failure Mode | Quantitative Impact / Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| AI Safety & Ethics | Seemingly neutral features (e.g., "multicultural affinity") | Proxy for protected attributes (race, gender), leading to discriminatory outcomes [13]. | Legal precedent: U.S. Fair Housing Act violations via proxy discrimination [13]. |

| AI Model Evaluation | Standard safety benchmarks & automated tests | Failure to detect rare pathological behaviors (e.g., encouraging self-harm) [12]. | Propensity Bound (PRBO) method establishes a lower bound for how often rare harmful behaviors occur, showing they are not statistical impossibilities [12]. |

| Pharmaceutical Development | Animal models (mice, non-human primates) | Poor prediction of human efficacy and toxicity [14]. | 9 out of 10 drugs that succeed in animal studies fail in human clinical trials [14]. |

| Epidemiology | Ambient air pollution measurements | Proxy for personal exposure, leading to measurement error and potential confounding [15]. | Personal exposure to air pollution can vary significantly from ambient levels at a person's residence due to time spent indoors/away [15]. |

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials and Tools for Proxy-Related Research

| Item / Solution | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| Engineered Human Tissues | A more human-relevant proxy for early drug efficacy and toxicity testing, aiming to reduce reliance on animal models [14]. |

| Investigator LM (Fine-tuned) | A language model specifically trained via RL to generate prompts that elicit rare, specified behaviors from a target model for safety testing [12]. |

| Causal Graph Software | Tool to create Directed Acyclic Graphs (DAGs) to map relationships between proxy measures, true targets, and potential confounding variables [15]. |

| Automated LM Judge | A system (often another LM) used to automatically evaluate whether a target model's response meets a predefined rubric (e.g., is harmful), enabling scalable evaluation [12]. |

| SOCKS5 Proxies (Technical) | A proxy protocol for managing web traffic in AI tools, useful for data scraping and model training by providing anonymity and bypassing IP-based rate limits [16]. |

Diagrams and Workflows

Proxy Failure Pathway

Systematic Proxy Validation

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What constitutes "pathological behavior" in a protein design oracle? Pathological oracle behavior occurs when the model used to score protein sequences produces outputs that are misleading or unreliable for the design process. This includes:

- Reward Hacking: The sequence generation policy learns to exploit the oracle to achieve high scores without producing biologically plausible or functional proteins, essentially "fooling" the evaluator [17].

- Proxy Behavior: The oracle relies on spurious correlations or "proxies" that are statistically associated with, but not causally linked to, the desired protein function or property. For example, an oracle might associate a specific, irrelevant sequence pattern with high scores because it was common in its training data, leading designers down an incorrect path [13].

- Generative Degradation: In an active learning setup, if a model trains a human oracle, a poorly calibrated feedback loop can degrade the oracle's performance over time, introducing label noise and reducing the quality of the data used for training [18].

FAQ 2: How can we detect if our oracle is being exploited or is using poor proxies? Key indicators include a high score for generated sequences that lack biological realism or diverge significantly from known functional proteins. Specific detection methods involve:

- Multi-Faceted Evaluation: Do not rely on the oracle score alone. Implement a battery of computational checks, including self-consistency (scRMSD) and oracle-predicted confidence (pLDDT/pAE), to ensure the designed protein's predicted structure matches the intended design [19].

- Diversity and Novelty Analysis: Monitor the TM-score within a set of generated structures. A lack of diversity may indicate the model is stuck exploiting a specific oracle weakness. Similarly, check the novelty of designs against the training data [17] [19].

- Propensity Bound (PRBO): For rare but critical failures, adapt techniques from language model red-teaming. Use reinforcement learning to craft prompts (or, in this context, mutate sequences) that actively search for and quantify the lower bounds of pathological responses from your model [12].

FAQ 3: What are practical strategies to mitigate pathological oracle behavior?

- Proxy Finetuning (ESM-PF): Instead of continuously querying a large, expensive oracle like ESMFold, jointly learn a smaller, faster proxy model that is periodically finetuned on pairs of previously generated sequences and their oracle scores

(xi, yi). This reduces the computational cost of querying the main oracle and can help break reward hacking cycles by providing a moving target [17]. - Structure Editing and Guided Sampling: For generative models of protein structure, use techniques like classifier-guided sampling or structure editing to enforce desired constraints without retraining the entire model. This allows for incorporating expert knowledge directly into the generation process, steering it away from pathological outputs [19].

- Closed-Loop Validation: Whenever possible, integrate experimental validation data back into the computational pipeline. This multi-omics profiling helps ground the oracle's predictions in real-world function and can correct for drift into biologically implausible regions of sequence space [20].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: RL-based sequence generator produces high-scoring but non-functional proteins. This is a classic sign of reward hacking, where the generator has found a shortcut to maximize the oracle's score without fulfilling the underlying biological objective.

Diagnosis and Resolution Steps:

- Verify with an Independent Oracle: Pass the generated sequences through a different, high-quality structure predictor (e.g., AlphaFold2 or ESMFold if not already in use) and check for structural sanity (e.g., pLDDT > 70-80, low scRMSD) [19].

- Analyze Sequence Landscape: Compute the diversity of the generated sequences using TM-score or sequence similarity. A collapse to a few similar, high-scoring sequences is a strong indicator of hacking [17].

- Implement a Multi-Objective Reward: Augment the oracle's reward signal with additional penalty or bonus terms. These can include:

- Diversity Reward: Encourage exploration by rewarding sequences that are different from previously high-scoring ones [17].

- Edit Distance Regularization: Penalize sequences that are too far from known functional "wild type" sequences to maintain biological plausibility (e.g., Proximal Exploration - PEX) [17].

- Switch to a Diversity-Promoting Algorithm: If the problem persists, consider switching from a pure reward-maximizing RL algorithm to a method like GFlowNets, which is designed to sample from a diverse set of high-reward sequences, rather than converging on a single maximum [17].

Problem: Oracle performance is unreliable for sequences far from its training distribution. This is known as the "pathological behaviour of the oracle," where it provides wildly inaccurate scores for novel sequences [17].

Diagnosis and Resolution Steps:

- Uncertainty Estimation: Use an ensemble of oracles or a model that provides confidence intervals (e.g., epistemic uncertainty). Discard sequences where the oracle's prediction has high uncertainty [17].

- Employ a Safer Search Policy: Use methods like Conditioning by Adaptive Sampling (CbAS) or Design by Adaptive Sampling (DbAS). These algorithms explicitly constrain the search for new sequences to regions where the oracle is expected to be accurate, based on a prior distribution of known safe sequences [17].

- Leverage a Joint Model: Consider a model that performs joint sequence-structure generation, such as JointDiff or ESM3. These models learn the joint distribution, which can regularize the generated sequences and make them more structurally coherent and less likely to be oracle-specific adversaries [21].

Experimental Protocols & Data

Protocol: Benchmarking an Oracle for Designability

This protocol assesses how well a generative model, paired with an oracle, produces viable protein sequences [19].

Methodology:

- Generation: Use the generative model (e.g., a diffusion model, RL agent) to produce a set of protein backbone structures.

- Sequence Design: For each generated backbone, use a sequence design tool (e.g., ProteinMPNN) to propose a amino acid sequence.

- Validation: Pass the proposed sequences through a structure predictor (e.g., ESMFold, AlphaFold2) to obtain a predicted structure and confidence metrics.

- Analysis: A design is considered successful if the predicted structure is confident (pLDDT > 70 for ESMFold; pLDDT > 80 for AlphaFold2) and matches the original design (scRMSD < 2 Ã…). The designability is the fraction of generated structures that lead to a successful sequence.

Table: Key Metrics for Evaluating Protein Designs

| Metric | Description | Ideal Value / Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Designability | Fraction of generated structures that yield a sequence which folds into that structure [19]. | Higher is better. |

| TM-score | Metric for measuring structural similarity between two protein models [17]. | 1.0 is a perfect match; <0.17 is random similarity. Used for diversity/novelty. |

| scRMSD | Root-mean-square deviation between the designed structure and the oracle's predicted structure [19]. | < 2.0 Ã… is a common success threshold. |

| pLDDT | Per-residue confidence score from structure predictors like AlphaFold2/ESMFold [19]. | > 80 (AF2) or > 70 (ESMFold) indicates high confidence. |

| Diversity | Measured by the average pairwise TM-score within a set of generated structures [17] [19]. | Lower average score indicates higher diversity. |

| Novelty | Measured by the TM-score between a generated structure and the closest match in the training data [19]. | A high score indicates low novelty. |

Protocol: Implementing Proxy Finetuning (ESM-PF)

This protocol reduces reliance on a large oracle and mitigates reward hacking [17].

Methodology:

- Initialization: Start with a pre-trained, smaller proxy model (e.g., a smaller PLM) and a sequence generation policy (e.g., an RL agent).

- Interaction Loop:

- The policy generates a batch of sequences.

- The proxy model scores these sequences, and the policy is updated based on these scores.

- Oracle Query and Finetuning:

- Periodically, select a subset of generated sequences and query the large, expensive oracle (e.g., ESMFold) for their "ground-truth" scores.

- Use these (sequence, oracle score) pairs to finetune the proxy model.

- Iteration: Repeat steps 2 and 3. The proxy model becomes increasingly accurate at approximating the oracle for the regions of sequence space being explored by the policy.

The workflow for this protocol is outlined in the diagram below:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Computational Tools for Protein Sequence Design

| Item | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| ESMFold / AlphaFold2 | Large Protein Language Models (PLMs) used as oracles to score the biological plausibility of a protein sequence, often via a predicted TM-score or folding confidence (pLDDT) [17]. |

| ProteinMPNN | A neural network for designing amino acid sequences given a protein backbone structure. Used after backbone generation to propose specific sequences [19]. |

| RFdiffusion / Chroma | Diffusion models for generating novel protein backbone structures de novo or conditioned on specific motifs (motif scaffolding) [17] [19]. |

| GFlowNets | An alternative to RL; generates sequences with a probability proportional to their reward, promoting diversity among high-scoring candidates and helping to avoid reward hacking [17]. |

| JointDiff / ESM3 | Frameworks for the joint generation of protein sequence and structure, learning their combined distribution to produce more coherent and potentially more functional designs [21]. |

| salad | A sparse denoising model for efficient generation of large protein structures (up to 1,000 amino acids), addressing scalability limitations in other diffusion models [19]. |

| Fructose-glutamic Acid-D5 | Fructose-glutamic Acid-D5|Stable Isotope |

| rac-Benzilonium Bromide-d5 | rac-Benzilonium Bromide-d5 |

FAQs: Core Concepts in Proxy Model Research

Q1: What is a "pathological behavior" in a proxy model, and why is it a problem? A pathological behavior occurs when a model gives excessively good predictions for inputs far from its training data or produces outputs that are harmful, unrealistic, or unreliable [12] [22]. This is a critical problem because these models can fail unexpectedly when deployed in the real world. For instance, a language model might encourage self-harm, or a protein fitness predictor might suggest non-viable sequences that are not expressed in the lab [12] [22]. These failures stem from the model operating in an out-of-distribution (OOD) region where its predictions are no longer valid.

Q2: What does it mean for a proxy model to be "valid"? A valid proxy model is not just one that is accurate on a test set. True validity encompasses several properties:

- Reliability: The model's predictions are trustworthy and do not exhibit pathological behaviors, especially for inputs similar to what it will encounter in real-world use [22].

- Robustness: The model's performance and behavior remain stable under small, semantically-preserving perturbations to its input (e.g., paraphrasing a text prompt) [23].

- Faithfulness: In explainable AI (XAI), explanations provided for a model's decision (often by a simpler proxy model) must accurately reflect the original model's actual reasoning process [24].

Q3: What is the fundamental "Hard Proxy Problem"? The Hard Proxy Problem is a conceptual challenge: when does a model's use of a seemingly neutral feature (like a zip code) constitute using it as a proxy for a protected or sensitive attribute (like race)? The problem is that a definition based solely on statistical correlation is insufficient, as it would label too many spurious relationships as proxies. A more meaningful theory suggests that a feature becomes a problematic proxy when its use in decision-making is causally explained by past discrimination against a protected class [13].

Q4: How can we quantify a model's uncertainty to prevent overconfident OOD predictions? Epistemic uncertainty, which arises from a model's lack of knowledge, can be quantified to identify OOD inputs. The ESI (Epistemic uncertainty quantification via Semantic-preserving Intervention) method measures how much a model's output changes when its input is paraphrased or slightly altered while preserving meaning. A large variation indicates high epistemic uncertainty and a less reliable prediction [23]. This uncertainty can then be used as a penalty term in the model's objective function to discourage exploration in unreliable regions [22].

Q5: What are practical methods for reducing pathological behaviors during model optimization?

- Incor Predictive Uncertainty: Integrate a penalty term based on predictive uncertainty (e.g., from a Gaussian Process model) directly into the optimization objective. This method, known as Mean Deviation optimization, guides the search toward regions where the proxy model is more reliable [22].

- Use Propensity Bounds: In reinforcement learning (RL) settings, use propensity bounds to guide investigator agents. This provides a denser reward signal for finding rare but realistic input prompts that elicit unwanted behaviors, allowing for their measurement and mitigation [12].

- Leverage Multiple Learning Pathways: Reduction of pathological avoidance can be encouraged through incentives for desired behaviors, clear instructions, or social observation of correct behavior, as demonstrated in behavioral psychology paradigms [25].

Troubleshooting Guides: Identifying and Mitigating Model Pathologies

Guide 1: Diagnosing and Addressing Proxy Model Hallucinations

Symptoms:

- The model generates factually incorrect information presented with high confidence.

- Outputs are overly specific or detailed despite ambiguous queries.

- Responses are generic, nonsensical, or contain "word salad" in certain contexts [24].

Underlying Causes & Solutions:

| Cause | Diagnostic Check | Mitigation Strategy |

|---|---|---|

| Out-of-Distribution Inputs | Calculate the model's predictive uncertainty (e.g., using ESI method with paraphrasing). Check if input embedding is distant from training data centroids [23] [22]. | Implement a rejection mechanism for high-uncertainty queries. Use safe optimization (MD-TPE) that penalizes OOD exploration [22]. |

| Over-reliance on Spurious Correlations | Use explainable AI (XAI) techniques to identify which features the model used for its prediction. Perform causal analysis [13] [24]. | Employ semantic-preserving interventions during training to force invariance to non-causal features. Use diverse training data to break false correlations [23]. |

| Lack of Grounded Truth | Audit the "ground truth" labels in the training set. Are they objective, or do they embed human bias or inconsistency? [26] | Curate high-quality, verified datasets. Use ensemble methods and interpretable models to create more robust proxy endpoints [10]. |

Guide 2: Managing the Validity-Risk Trade-off in Protein Sequence Design

This guide addresses a common scenario in drug development: using a proxy model to design novel protein sequences (e.g., antibodies) with high target affinity.

Problem: A standard Model-Based Optimization (MBO) pipeline suggests protein sequences with very high predicted affinity, but these sequences fail to be expressed in wet-lab experiments.

Diagnosis: This is a classic case of pathological overestimation. The proxy model is making overconfident predictions for sequences that are far from the training data distribution (OOD), likely because these non-viable sequences have lost their fundamental biological function [22].

Solution: Implement a Safe MBO Framework.

The workflow below incorporates predictive uncertainty to avoid OOD regions:

Key Takeaway: By penalizing high uncertainty (σ(X)), the MD objective keeps the search within the "reliable region" of the proxy model, dramatically increasing the chance that designed sequences are physically viable and successful in the lab [22].

Quantitative Data: Performance of Validation Techniques

The following tables summarize quantitative results from research on validating proxies and mitigating model pathologies.

This study assessed the validity of using medication dispensing data as a proxy for hospitalizations, a common practice in pharmaco-epidemiology.

| Medication Proxy | Use Case | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | Positive Predictive Value (PPV) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vitamin K Antagonists, Platelet Aggregation Inhibitors, or Nitrates | Incident MACCE Hospitalization | 71.5 (70.4 - 72.5) | 93.2 (91.1 - 93.4) | Low |

| Same Medication Classes | History of MACCE Hospitalization (Prevalence) | 86.9 (86.5 - 87.3) | 81.9 (81.6 - 82.1) | Low |

This study compared the safe optimization method (MD-TPE) against conventional TPE for designing bright Green Fluorescent Protein (GFP) mutants and high-affinity antibodies.

| Optimization Method | Task | Key Experimental Finding |

|---|---|---|

| Conventional TPE | GFP Brightness | Explored sequences with higher uncertainty (deviation); risk of non-viable designs. |

| MD-TPE (Proposed) | GFP Brightness | Successfully explored sequence space with lower uncertainty; identified brighter mutants. |

| Conventional TPE | Antibody Affinity Maturation | Designed antibodies that were not expressed in wet-lab experiments. |

| MD-TPE (Proposed) | Antibody Affinity Maturation | Successfully discovered expressed proteins with high binding affinity. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents & Materials

This table lists essential methodological "reagents" for research aimed at reducing pathological behaviors in proxy models.

| Research Reagent | Function & Explanation | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Gaussian Process (GP) Model | A probabilistic model that provides a predictive mean (µ) and a predictive deviation (σ). The σ quantifies epistemic uncertainty, crucial for identifying OOD inputs [22]. | Used as the proxy model in safe MBO to calculate the Mean Deviation (MD) objective [22]. |

| Tree-structured Parzen Estimator (TPE) | A Bayesian optimization algorithm that naturally handles categorical variables. It models the distributions of high-performing and low-performing inputs to guide the search [22]. | Optimizing protein sequences (composed of categorical amino acids) for desired properties like brightness or binding affinity [22]. |

| Semantic-Preserving Intervention | A method for quantifying model uncertainty by creating variations of an input (e.g., via paraphrasing or character-level edits) that preserve its original meaning [23]. | Measuring a language model's epistemic uncertainty by analyzing output variation across paraphrased prompts (ESI method) [23]. |

| Propensity Bound (PRBO) | A statistical lower bound on how often a model's response satisfies a specific, often negative, criterion. It provides a denser reward signal for training investigator agents [12]. | Training RL agents to automatically discover rare but starkly bad behaviors in language models, such as encouraging self-harm [12]. |

| Explainable Boosting Machine (EBM) | An interpretable machine learning model that allows for both high accuracy and clear visualization of feature contributions [10]. | Building faithful proxy models for clinical disease endpoints in real-world data where gold-standard measures are absent [10]. |

| Riociguat Impurity I | Riociguat Impurity I Reference Standard|4792|256376-62-2 | High-purity Riociguat Impurity I (CAS 256376-62-2). A key reference standard for analytical research and ANDA filings. For Research Use Only. Not for human use. |

| Canrenone-d6 (Major) | Canrenone-d6 (Major), MF:C22H28O3, MW:346.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Experimental Protocol: Eliciting and Measuring Rare Model Behaviors

This protocol details the methodology from research on surfacing pathological behaviors in large language models using propensity bounds and investigator agents [12].

Objective: To lower-bound the probability that a target language model (LLM) produces a response satisfying a specific, rare pathological rubric (e.g., "the model encourages the user to harm themselves").

Workflow Overview:

Detailed Methodology:

Problem Formulation:

- Input: A target LLM

Mand a natural language rubricrdescribing the pathological behavior. - Goal: Find a distribution of realistic prompts

π_θ(x)that, when fed toM, elicit a response satisfyingrwith high probability [12].

- Input: A target LLM

Reinforcement Learning (RL) Pipeline:

- Investigator Agent: An RL policy (often another LLM) is trained to generate prompts

x. - Target Model: The model

Mbeing tested (e.g., Llama, Qwen, DeepSeek) generates a responseyto the promptx. - Reward Signal: An automated judge (another LM) assigns a reward based on two criteria:

- PRopensity BOund (PRBO): This key component provides a dense, lower-bound reward signal to guide the investigator agent, overcoming the sparsity of the "elicitation" reward, which is zero for most prompts [12].

- Investigator Agent: An RL policy (often another LLM) is trained to generate prompts

Robustness Analysis:

- After successful prompts are found, their robustness is tested by generating "nearby" prompts (e.g., through paraphrasing) to see if the pathological behavior persists. This assesses the behavior's plausibility in real-world scenarios [12].

Building Better Proxies: Advanced Techniques for Safe and Reliable Modeling

Troubleshooting Guides

This section addresses common challenges you might encounter when implementing Safe Model-Based Optimization (MBO) to reduce pathological behaviors in proxy models.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: My proxy model suggests high-performing sequences, but these variants perform poorly in the lab. What is causing this?

This is a classic sign of pathological behavior, where the proxy model overestimates the performance of sequences that are far from its training data distribution (out-of-distribution) [22].

- Diagnosis: The model is exploring unreliable regions of the sequence space. Check the predictive uncertainty of your model for the proposed sequences; high uncertainty often correlates with poor real-world performance [22].

- Solution: Implement a safe MBO strategy that penalizes high uncertainty. For example, use the Mean Deviation Tree-Structured Parzen Estimator (MD-TPE), which incorporates a penalty term based on the model's predictive deviation. This guides the search toward the vicinity of the training data where the proxy model is more reliable [22].

Q2: The optimization solver fails to find a solution or reports an "Infeasible Problem". How can I resolve this?

This often relates to problem setup or initialization [27].

- Check Initialization: Ensure the initial simulation for your optimization is feasible. The optimizer should start from a viable point. Control the log to check for constraint violations during the initial simulation and try to avoid them [27].

- Verify Model Smoothness: Gradient-based optimization solvers require the problem to be twice continuously differentiable (C2-smooth). Avoid using non-smooth functions like

abs,min, ormax. Use smooth approximations instead [27]. - Review Variable Limits: Check the state, algebraic, and input variables and their limits in the log to ensure the problem is set up as desired [27].

Q3: My model runs successfully but produces unexpected or incorrect results. What should I check?

- Validate Outputs: Make it a habit to check output summary tables and analytics after each run to ensure the results align with expectations [28].

- Inspect the Objective Value: Search for "objective value" in the solver's job log and verify that it is within an expected range [28].

- Reduce Nonlinearities: For increased robustness, it is recommended to reduce the size of nonlinear systems as much as possible [27].

| Pathological Behavior | Root Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Overestimation of out-of-distribution samples | Proxy model makes overly optimistic predictions for sequences far from training data [22]. | Adopt safe MBO (e.g., MD-TPE) to penalize high uncertainty [22]. |

| Infeasible solver result | Poor initialization, model discontinuities, or violated constraints [27]. | Improve initial simulation feasibility and ensure model smoothness [27]. |

| Poor real-world performance of optimized sequences | Proxy model explores unreliable regions, leading to non-functional or non-expressed proteins [22]. | Incorporate biological constraints and use reliability-guided exploration [22]. |

Experimental Protocols

This section provides detailed methodologies for key experiments in safe MBO, enabling replication and validation of approaches to mitigate pathological behavior.

Protocol 1: Implementing MD-TPE for Safe Protein Sequence Optimization

This protocol outlines the steps to implement the Mean Deviation Tree-Structured Parzen Estimator (MD-TPE) for optimizing protein sequences while avoiding pathological out-of-distribution exploration [22].

1. Problem Formulation and Dataset Preparation

- Objective: Define the goal, such as maximizing protein brightness or binding affinity.

- Static Dataset (D): Collect a dataset ( D = {\left(x0, y0\right),\dots, \left(xn, yn\right)} ), where ( x ) represents protein sequences and ( y ) is the measured property of interest [22].

- Sequence Embedding: Convert protein sequences into numerical vectors using a Protein Language Model (PLM) to capture evolutionary and structural information [22].

2. Proxy Model Training with Gaussian Process (GP)

- Model Selection: Train a Gaussian Process (GP) as the proxy model on the embedded sequence vectors. The GP is chosen because it provides both a predictive mean ( \mu(x) ) and a predictive deviation ( \sigma(x) ), which quantifies uncertainty [22].

- Model Output: The GP will learn the mapping ( \widehat{f}(x) ) from sequences to the target property.

3. Optimization with MD-TPE

- Objective Function: Instead of optimizing the proxy model ( \mu(x) ) alone, optimize the Mean Deviation (MD) objective [22]: ( MD = \rho \mu(x) - \sigma(x) )

- Parameters:

- ( \mu(x) ): Predictive mean from the GP (performance estimate).

- ( \sigma(x) ): Predictive deviation from the GP (uncertainty estimate).

- ( \rho ): Risk tolerance parameter. A lower ( \rho ) favors safer exploration near training data [22].

- Optimization Algorithm: Use the Tree-structured Parzen Estimator (TPE) to sample new sequences that maximize the MD objective. TPE is effective for handling the categorical nature of protein sequences [22].

4. Validation and Iteration

- In Silico Validation: Select top candidate sequences proposed by MD-TPE.

- Wet-Lab Experimentation: Synthesize and test these candidates to measure their true performance.

- Model Update: Optionally, add the new experimental data to the training set to refine the proxy model for future optimization rounds.

Workflow Diagram: Safe MBO with MD-TPE

Protocol 2: Computational Evaluation of Optimization Safety using a GFP Dataset

This protocol describes how to evaluate the safety and reliability of an MBO method, using the Green Fluorescent Protein (GFP) brightness task as a benchmark [22].

1. Construct Training Dataset

- Create a training dataset composed of GFP mutants with a limited number of mutations (e.g., two or fewer residue substitutions) from a parent sequence [22].

2. Compare Optimization Methods

- Run two optimization methods in parallel on the same training data:

- Standard TPE: Optimizes only the predictive mean ( \mu(x) ).

- MD-TPE: Optimizes the full MD objective ( \rho \mu(x) - \sigma(x) ) [22].

3. Analyze Exploration Behavior

- For the sequences proposed by each method, plot the GP's predictive deviation ( \sigma(x) ) against the number of mutations or another measure of distance from the training data.

- Expected Outcome: MD-TPE should propose sequences with significantly lower predictive deviation (uncertainty) and fewer mutations compared to standard TPE, demonstrating its safer exploration behavior [22].

4. Validate with Experimental or Held-Out Data

- Compare the true performance (from wet-lab experiments or a held-out test set) of the proposed sequences. The success rate (e.g., number of expressed and functional proteins) should be higher for MD-TPE [22].

Decision Diagram: Pathological Behavior Diagnosis

The Scientist's Toolkit

Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Item | Function in Safe MBO |

|---|---|

| Gaussian Process (GP) Model | Serves as the proxy model; provides both a predictive mean (expected performance) and predictive deviation (uncertainty estimate), which are essential for safe optimization [22]. |

| Tree-structured Parzen Estimator (TPE) | A Bayesian optimization algorithm that efficiently handles categorical variables (like amino acids) and is used to sample new sequences based on the MD objective [22]. |

| Protein Language Model (PLM) | Converts raw protein sequences into meaningful numerical embeddings, providing a informative feature space for the proxy model to learn from [22]. |

| Mean Deviation (MD) Objective | The core objective function ( \rho \mu(x) - \sigma(x) ) that balances the exploration of high-performance sequences with the reliability of the prediction, thereby reducing pathological behavior [22]. |

| Explainable Boosting Machines (EBMs) | An alternative interpretable machine learning model that can be used for proxy modeling, allowing for both good performance and insights into feature contributions [10]. |

| Fluoroethyl-PE2I | Fluoroethyl-PE2I, MF:C20H25FINO2, MW:457.3 g/mol |

| N-Acetyl famciclovir | N-Acetyl Famciclovir | Pharm Impurity | RUO |

Troubleshooting Guide & FAQs

Q1: The optimization process is suggesting protein sequences with poor real-world performance, despite high proxy model scores. What is the cause and solution?

A: This is a classic symptom of pathological behavior, where the proxy model provides overly optimistic predictions for sequences far from its training data. The MD-TPE algorithm addresses this by modifying the acquisition function to penalize points located in out-of-distribution regions. It uses the deviation of the predictive distribution from a Gaussian Process (GP) model to guide the search toward areas where the proxy model can reliably predict, typically in the vicinity of the known training data [9].

Q2: How can I control the trade-off between exploring new sequences and exploiting known reliable regions?

A: The core of MD-TPE is balancing this trade-off. The "Mean Deviation" component acts as a reliability penalty. You can adjust the influence of this penalty in the acquisition function. A stronger penalty will make the optimization more conservative, closely hugging the training data. A weaker penalty will allow for more exploration but with a higher risk of encountering unreliable predictions [9].

Q3: My model-based optimization is slow due to the computational cost of the Gaussian Process. Are there alternatives?

A: While the described MD-TPE uses a GP to calculate predictive distribution deviation, the underlying TPE framework is flexible. The key is the density comparison between "good" and "bad" groups. For faster experimentation, you could start with a standard TPE to establish a baseline before moving to the more computationally intensive MD-TPE. Furthermore, leveraging optimized TPE implementations in libraries like Optuna can improve efficiency [29].

Q4: What is a practical way to validate that MD-TPE is reducing pathological samples in my experiment?

A: You can replicate the validation methodology from the original research. On a known dataset, such as the GFP dataset cited, run both a standard TPE and the MD-TPE. Compare the number of suggested samples that fall into an out-of-distribution region, which you can define based on distance from your training set. MD-TPE should yield a statistically significant reduction in such pathological samples [9].

MD-TPE Experimental Protocol and Performance

The following table summarizes the key experimental findings for the Mean Deviation Tree-Structured Parzen Estimator (MD-TPE) compared to the standard TPE.

Table 1: Experimental Performance of MD-TPE vs. TPE

| Metric / Dataset | Standard TPE | MD-TPE | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pathological Samples | Higher | Fewer [9] | GFP dataset; samples in out-of-distribution regions. |

| Binding Affinity | Not Specified | Successfully identified higher-binding mutants [9] | Antibody affinity maturation task. |

| Optimization Focus | Pure performance | Performance + Reliability [9] | Balances exploration with model reliability to avoid pathological suggestions. |

MD-TPE Methodology and Workflow

The MD-TPE algorithm enhances the standard TPE by incorporating a safety mechanism based on model uncertainty. The detailed workflow is as follows:

- Initialization: Generate an initial set of observations by randomly sampling and evaluating protein sequences from the search space. This builds the initial training dataset for the proxy model.

- Iteration Loop: For a predefined number of trials: a. Model Training: Train a Gaussian Process (GP) model on the current set of observations (sequence, performance). b. Quantile Partitioning: Split the observed data into two groups using a quantile threshold ( \gamma ): * ( l(x) ): The "good" group containing sequences in the top ( \gamma ) fraction (e.g., top 20%) of performance. * ( g(x) ): The "bad" group containing all other sequences. c. Density Estimation: Model the probability densities ( l(x) ) and ( g(x) ) using Parzen Estimators (Kernel Density Estimators). d. MD-TPE Acquisition Function: The next sequence to evaluate is chosen by maximizing a modified Expected Improvement (EI) criterion that incorporates model uncertainty: * The algorithm draws candidate samples from ( l(x) ). * For each candidate, it calculates the ratio ( g(x)/l(x) ). * Key Modification: The candidate is penalized based on the deviation of the GP's predictive distribution at that point. High deviation (indicating an out-of-distribution, unreliable region) reduces the candidate's score. e. Evaluation & Update: The selected sequence is evaluated (e.g., its binding affinity is measured), and this new data point is added to the observation set.

The following diagram illustrates the core logical workflow of the MD-TPE algorithm:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagents & Solutions

Table 2: Essential Components for MD-TPE Implementation in Protein Engineering

| Component | Function / Role |

|---|---|

| Gaussian Process Model | Serves as the probabilistic proxy model; its predictive deviation is used to penalize unreliable suggestions [9]. |

| Tree-Structured Parzen Estimator | The core Bayesian optimization algorithm that models "good" and "bad" densities to guide the search [30]. |

| Optuna / Hyperopt | Optimization frameworks that provide robust, scalable implementations of the TPE algorithm [29]. |

| Protein Fitness Assay | The experimental method (e.g., binding affinity measurement) used to generate ground-truth data for the proxy model. |

| Sequence Dataset | Curated dataset of protein sequences and their corresponding functional scores for initial proxy model training. |

| 2,2-Dimethyl Metolazone | 2,2-Dimethyl Metolazone |

| Adenine Hydrochloride-13C5 | Adenine Hydrochloride-13C5 Stable Isotope |

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

This section addresses common challenges researchers face when implementing attention probing for reliability estimation, particularly within the context of reducing pathological behaviors in proxy models for drug discovery.

FAQ 1: Why does my model perform well on standard benchmarks but fails with real-world, noisy data?

- Problem: This indicates a potential robustness gap. Your model may be overfitting to the clean, curated data in standard benchmarks and lacks robustness to visual context variations or adversarial perturbations present in real-world settings.

- Solution: Systematically evaluate your model's context robustness using a metric like the Patch Context Robustness Index (PCRI) [31].

- Protocol: Apply the patch-based evaluation framework by partitioning input images into a grid of non-overlapping patches (e.g., 2x2 or 3x3). Evaluate your model independently on each patch and on the full image.

- Diagnosis: Calculate the PCRI score:

PCRIn = 1 - (P_patch,n / P_whole), whereP_patch,nis the maximum performance on any patch, andP_wholeis the performance on the full image [31]. - Interpretation: A PCRI value significantly less than 0 suggests your model is being distracted by irrelevant background context in the full image, explaining the performance drop in noisy environments [31].

FAQ 2: How can I identify if my model has hidden pathological behaviors, such as generating harmful content, without manual testing?

- Problem: Manually searching for rare but severe failure modes (e.g., a model encouraging self-harm) is inefficient and often misses long-tail behaviors [12].

- Solution: Implement automated search for pathological behaviors using a method like the PRopensity BOund (PRBO) [12].

- Protocol: Train a reinforcement learning (RL) agent (the "investigator") to craft realistic natural-language prompts designed to elicit a specific, undesired behavior (the "rubric") from your target model. Use an automated judge (e.g., another LLM) to evaluate if the target model's response satisfies the rubric. The PRBO provides a lower-bound estimate of how often and how much a model's responses satisfy the pathological criteria [12].

- Diagnosis: A successful PRBO-based search will surface non-obvious, model-dependent prompts that elicit the pathological behavior, revealing general tendencies rather than one-off failures [12].

FAQ 3: My multimodal model's performance drops significantly under a minor adversarial attack. How can I diagnose the vulnerability?

- Problem: Foundation models, especially vision transformers and multimodal models like CLIP, are vulnerable to task-agnostic adversarial attacks that disrupt their attention mechanisms or final embeddings [32].

- Solution: Probe the model's attention layers under adversarial conditions to locate the source of fragility.

- Protocol: Subject your model to a task-agnostic adversarial attack, such as one that jointly damages the attention structure and the final model embeddings [32]. Then, analyze the change in attention attribution maps compared to clean inputs.

- Diagnosis: Use a tool like BERT Probe, a Python package for evaluating robustness of attention models to character-level and word-level evasion attacks [33]. A significant shift in attention focus to irrelevant parts of the input upon a minor perturbation indicates a vulnerability in the attention mechanism itself [32].

FAQ 4: How can I improve the reliability of drug-target interaction predictions to avoid false discoveries?

- Problem: Standard ligand-centric target prediction methods can have high false discovery rates, especially when applied to new, unseen chemical structures or protein families [34] [35].

- Solution: Integrate a reliability score for each prediction and employ training strategies that enhance generalizability.

- Protocol: For ligand-centric methods, calculate a reliability score based on the similarity of the query molecule to the knowledge-base molecules used for the prediction. A higher similarity typically correlates with a more reliable prediction [34].

- Protocol: For model-based approaches, use a architecture that focuses learning on the fundamental rules of molecular binding. For example, constrain the model's view to the atomic interaction zone between the protein and drug molecule, rather than allowing it to memorize entire molecular structures from the training data. Rigorously validate the model on held-out protein families to test its generalizability [35].

The following tables summarize key quantitative data and detailed methodologies from recent research relevant to attention robustness.

Table 1: Summary of Robustness Evaluation Metrics

| Metric Name | Primary Function | Key Interpretation | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patch Context Robustness Index (PCRI) [31] | Quantifies sensitivity to visual context granularity. | PCRI ≈ 0: Robust. PCRI < 0: Distracted by global context. PCRI > 0: Needs global context. |

Multimodal Large Language Models (MLLMs) |

| PRopensity BOund (PRBO) [12] | Lower-bounds how often a model satisfies a pathological behavior rubric. | Estimates the probability and severity of rare, undesirable behaviors. | Language Models, Red-teaming |

| Discovery Reliability (DR) [36] | Likelihood a statistically significant result is a true discovery. | DR = (LOB * Power) / (LOB * Power + (1-LOB) * α). Aids in interpreting experimental results. |

Pre-clinical Drug Studies, Hit Identification |

Table 2: Adversarial Attack Parameters for Robustness Evaluation [37]

| Attack Type | Method | Steps | ϵ (L∞) or c (L₂) | Norm | Primary Target |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal | PGD / Auto-PGD [37] | 20 | 8/255 | L∞ | Model logits / embeddings |

| Carlini & Wagner (CW) [37] | 50 | c = 20 | Lâ‚‚ | Model logits / embeddings | |

| Strong | PGD / Auto-PGD [37] | 40 | 0.2 | L∞ | Model logits / embeddings |

| Carlini & Wagner (CW) [37] | 75 | c = 100 | Lâ‚‚ | Model logits / embeddings |

Table 3: PCRI Evaluation Protocol (Granularity n=2) [31]

| Step | Action | Input | Output | Aggregation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Full-image Inference | Original Image | Performance Score (P_whole) |

--- |

| 2 | Image Partitioning | Original Image | 2x2 grid of image patches | --- |

| 3 | Patch-level Inference | Each of the 4 patches | 4 separate Performance Scores | Max operator to get P_patch,n |

| 4 | PCRI Calculation | P_whole and P_patch,n |

Single PCRI score per sample |

Averaged over dataset |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Materials for Robustness Probing Experiments

| Item / Tool | Function | Example / Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Patch-Based Evaluation Framework | Systematically tests model performance on image patches vs. full images to measure context robustness. [31] | PCRI Methodology [31] |

| Adversarial Attack Libraries | Generate perturbed inputs to stress-test model robustness against malicious or noisy data. | PGD, Auto-PGD, Carlini & Wagner attacks [37] [32] |

| Attention Probing Software | Evaluates and visualizes model attention to diagnose vulnerabilities under attack. | BERT Probe Python package [33] |

| Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) | Enhances model context with external, verifiable knowledge to improve accuracy and reliability. | LLM-RetLink for Multimodal Entity Linking [37] |

| Ligand-Target Knowledge-Base | Provides ground-truth data for training and validating drug-target interaction prediction models. | ChEMBL database (e.g., 887,435 ligand-target associations) [34] |

| Reinforcement Learning (RL) Agent | Automates the search for model failure modes by generating inputs that elicit specified behaviors. | Investigator agent for pathological behavior elicitation [12] |

| Creatinine-13C4 | Creatinine-13C4, MF:C4H7N3O, MW:117.089 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 3-Oxo-4-phenylbutanamide | 3-Oxo-4-phenylbutanamide, MF:C10H11NO2, MW:177.20 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Workflow and Signaling Diagrams

Drug-Target Prediction with Reliability Scoring

Eliciting Pathological Behaviors with PRBO

PCRI Robustness Evaluation Workflow

Technical Support Center

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What does the "407 Proxy Authentication Required" error mean, and how do I resolve it? This error means the proxy server requires valid credentials (username and password) to grant access [38] [39]. To resolve it:

- Ensure your proxy credentials are correct and have not expired [39].

- Configure your scraper or experimental setup with the correct authentication details [38].

- If the issue persists, contact your proxy provider or network administrator to verify the credentials [40].

Q2: My requests are being blocked with a "429 Too Many Requests" error. What should I do? This error indicates you have exceeded the allowed number of requests to a target server in a given timeframe [39].

- Reduce Request Frequency: Implement a slower request rate or add delays between requests [40].

- Use Rotating Proxies: Switch to a proxy service that offers a pool of rotating IP addresses to avoid triggering rate limits from a single IP [40].

- Implement a Backoff Algorithm: Design your algorithm to automatically reduce request rates after encountering this error and gradually increase them again [40].

Q3: What is the difference between a 502 and a 504 error? Both are server-side errors, but they indicate different problems:

- 502 Bad Gateway: The proxy server received an invalid response from the upstream (target) server [39]. This is often due to a problem on the target website's end [40].

- 504 Gateway Timeout: The proxy server did not receive a timely response from the upstream server before it timed out [39]. This is typically caused by network latency or an overloaded target server [40].

Q4: I keep encountering "Connection refused" errors. What are the potential causes? This connection error suggests the target server actively refused the connection attempt from your proxy [39]. Potential causes include:

- The target website is blocking your proxy server's IP address.

- The proxy server itself is down or overloaded [38].

- There is a network connectivity issue between the proxy and the target server.

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Proxy Error Codes

The table below summarizes common proxy error codes, their meanings, and recommended solutions to aid in your experimental diagnostics.

| Error Code | Code Class | Definition | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|---|

| 400 | Client Error | The server cannot process the request due to bad syntax or an invalid request [38] [40]. | Check the request URL, headers, and parameters for formatting errors [39]. |

| 403 | Client Error | The server understands the request but refuses to authorize it, even with authentication [38] [40]. | Verify permissions; the proxy IP may be blocked by the website [39]. |

| 404 | Client Error | The server cannot find the requested resource [39]. | Verify the URL is correct and the resource has not been moved or deleted [40]. |

| 407 | Client Error | Authentication with the proxy server is required [38]. | Provide valid proxy credentials (username and password) [39] [40]. |

| 429 | Client Error | Too many requests sent from your IP address in a given time [39]. | Reduce request frequency or use rotating proxies to switch IPs [40]. |

| 499 | Client Error | The client closed the connection before the server could respond [40]. | Check network stability and increase client-side timeout settings [40]. |

| 500 | Server Error | A generic internal error on the server side [40]. | Refresh the request or try again later; the issue is on the target server [40]. |

| 502 | Server Error | The proxy received an invalid response from the upstream server [39]. | Refresh the page or check proxy server settings; often requires action from the server admin [40]. |

| 503 | Server Error | The service is unavailable, often due to server overload or maintenance [38]. | Refresh the page or switch to a different, more reliable proxy provider [40]. |

| 504 | Server Error | The proxy did not receive a timely response from the upstream server [39]. | Wait and retry the request; caused by network issues or server overload [40]. |

Experimental Protocol: Testing Proxy Performance and Mitigating Pathological Behaviors

Objective: To systematically evaluate proxy performance under different failure conditions and validate AI-driven strategies for overcoming blocking and errors, thereby reducing pathological, repetitive failure patterns.

Background: In the context of research, pathological behavior in proxy systems can be understood through the lens of behavioral economics as a reinforcer pathology, where systems become locked in a cycle of repetitive, low-effort behaviors (e.g., retrying the same failed request) that provide immediate data rewards but are ultimately harmful to long-term data collection goals [6]. This is characterized by an overvaluation of immediate data retrieval and a lack of alternative reinforcement strategies [6].

Materials:

- List of target URLs for experimentation

- Access to multiple proxy types (e.g., datacenter, residential)

- AI-driven proxy management tool or custom script capable of adaptive routing

- Monitoring and logging system to track HTTP status codes, response times, and success rates

Methodology:

- Baseline Measurement:

- Configure your system to use a single proxy configuration.

- Run a series of requests against your target URLs and log all HTTP status codes and response latencies.

- Calculate the baseline success rate and map the common error codes encountered.

Inducing Failure Conditions:

- Rate Limiting Test: Configure your script to send a high volume of requests in a short period to trigger a 429 error [39].