In Silico Validation for Computational Protein Assessment: Methods, Challenges, and Future Directions

This article provides a comprehensive overview of in silico validation for computational protein assessment, a field revolutionizing therapeutic discovery and biotechnology.

In Silico Validation for Computational Protein Assessment: Methods, Challenges, and Future Directions

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of in silico validation for computational protein assessment, a field revolutionizing therapeutic discovery and biotechnology. It explores the foundational principles of computational protein design, detailing key methodological shifts from energy-based to AI-driven approaches. The content covers practical applications in drug discovery and antibody engineering, addresses common troubleshooting and optimization challenges, and examines rigorous validation frameworks and performance comparisons of various tools. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this review synthesizes current capabilities and limitations, offering insights into the future of computationally accelerated protein design and its impact on biomedical research.

The Foundations of Computational Protein Design: From Energy Functions to AI

The computational design of proteins represents a frontier in biotechnology, enabling the creation of novel biomolecules for therapeutic, catalytic, and synthetic biology applications. This field is structured around three core methodological paradigms: template-based modeling, which leverages evolutionary information from known structures; sequence optimization, which identifies amino acid sequences that stabilize a given backbone; and de novo design, which generates entirely new protein structures and folds not found in nature. These approaches operate across a spectrum from evolutionary conservation to novel creation, collectively expanding our access to the protein functional universe—the vast theoretical space of all possible protein sequences, structures, and activities. Advances in artificial intelligence and machine learning are now revolutionizing all three paradigms, accelerating the exploration of previously inaccessible regions of the protein sequence-structure landscape and enabling the systematic engineering of proteins with customized functions [1].

Template-Based Protein Structure Modeling

Conceptual Foundation and Applications

Template-based protein structure modeling, also known as comparative modeling, operates on the paradigm that proteins with similar sequences and/or structures form similar complexes [2]. This approach leverages the rich evolutionary information contained within experimentally determined structures in the Protein Data Bank (PDB) to predict the structure of a target protein based on its similarity to known template structures. The methodology significantly expands structural coverage of the interactome and performs particularly well when good templates for the target complex are available. Template-based docking is less sensitive to the quality of individual protein structures compared to free docking methods, making it robust for docking protein models that may contain inherent inaccuracies [2]. This approach has proven valuable for predicting protein-protein interactions, modeling multi-domain proteins, and providing initial structural hypotheses for proteins with limited characterization.

Protocol: Template-Based Modeling with Multiple Templates

Objective: Generate an accurate structural model of a target protein sequence using multiple template structures to improve model quality and coverage.

Materials and Software Requirements:

- Target protein sequence in FASTA format

- TASSER(VMT) software (available from http://cssb.biology.gatech.edu/)

- Threading algorithms (e.g., SP3, HHsearch) for initial template identification

- Structural alignment tool (e.g., TM-align) for comparing target and template structures

- Computational resources: Cluster or high-performance computing node recommended for larger targets

Methodology:

Template Identification and Initial Alignment:

- Perform sequence-based searches against protein structure databases (e.g., PDB) using iterative hidden Markov models (HMMs) as implemented in HH-suite [2].

- Generate multiple target-template alignments using complementary methods including SP3 threading, HHsearch, and MUSTER to maximize template coverage [3].

- Select templates based on significance scores (E-value, probability scores) and structural coverage of the target sequence.

Alignment Refinement through Short Simulations:

- For each promising template, generate an alternative alignment (SP3 alternative alignment) using a parametric alignment method coupled with short TASSER refinement [3].

- Select refined models using knowledge-based scores and structurally align the top model to the template to produce improved alignments.

- Combine all generated alignments (SP3 alternative, HHsearch, and original threading alignments) to create a comprehensive set of target-template alignments.

Multiple Template Integration and Model Generation:

- Group templates into sets containing variable numbers of template/alignment combinations (VMT approach) [3].

- For each template set, run short TASSER simulations to build full-length models using the assembly of template fragments.

- Pool models from all template sets and select the top 20-50 models using the FTCOM ranking method, which evaluates model quality based on structural features and knowledge-based potentials.

Final Model Refinement:

- Subject the selected top models to a single longer TASSER refinement run for final prediction.

- Validate the final model using statistical potential scores, stereochemical quality checks, and consensus among alternative models.

- For protein-protein complexes, use interface-based structural alignment when conformational changes upon binding are suspected [2].

Table 1: Performance Metrics of TASSER(VMT) on Benchmark Datasets

| Target Difficulty | Number of Targets | Average GDT-TS Improvement | Comparison to Pro-sp3-TASSER |

|---|---|---|---|

| Easy Targets | 874 | 3.5% | Outperforms |

| Hard Targets | 318 | 4.3% | Outperforms |

| CASP9 Easy | 80 | 8.2% | Outperforms |

| CASP9 Hard | 32 | 9.3% | Outperforms |

Workflow Visualization

Sequence Optimization for Fixed Backbone Design

Principles and Energy Functions

Sequence optimization for fixed backbone design addresses the inverse protein folding problem: given a predetermined protein backbone structure, identify amino acid sequences that will fold into that specific conformation. This paradigm is central to nearly all rational protein engineering problems, enabling the design of therapeutics, biosensors, enzymes, and functional interfaces [4]. Conventional approaches employ carefully parameterized energy functions that combine physical force fields with knowledge-based statistical potentials to guide sequence selection. These energy functions typically include terms for van der Waals interactions, hydrogen bonding, electrostatics, and solvation effects, and they are used to score sequences during conformational sampling. The development of accurate energy functions represents a significant focus in computational protein design, with continual refinements improving their ability to distinguish stable, foldable sequences from non-functional ones [5].

Protocol: Learned Potential-Based Sequence Design

Objective: Design novel protein sequences for a fixed backbone structure using a deep learning approach that learns directly from structural data without human-specified priors.

Materials and Software Requirements:

- Target protein backbone (PDB format with N, Cα, C, O, and OXT atoms)

- 3D convolutional neural network model trained on CATH 4.2 S95 domains

- Computational resources: GPU acceleration recommended for network inference

- Analysis tools: Rosetta or similar package for structural validation

Methodology:

Backbone Preparation and Environment Encoding:

- Input the target backbone structure with defined atomic positions for N, Cα, C, O, and the C-terminal oxygen atom.

- For each residue position i, encode the local chemical environment (envi) comprising neighboring backbone atoms and adjacent residues.

- Represent the environment using 3D voxelization or geometric graphs capturing spatial relationships and chemical features.

Autoregressive Sequence and Rotamer Sampling:

- Iteratively sample sequences and side-chain conformations residue-by-reside using autoregressive conditional sampling:

- For each position i, predict the amino acid distribution pθ(ri∣envi) conditioned on the local environment.

- Sample an amino acid type from the predicted distribution.

- For the selected amino acid, sequentially predict side-chain torsion angles χi1 through χi4 using the conditional distributions pθ(χij∣χi1:j-1,ri,envi).

- Repeat the process across all positions to generate complete sequences with full-atom side-chain placements.

- Iteratively sample sequences and side-chain conformations residue-by-reside using autoregressive conditional sampling:

Sequence Evaluation and Optimization:

- Calculate the pseudo-log-likelihood (PLL) for designed sequences using: PLL(Y∣X) = Σi log pθ(yi∣envi)

- Optimize sequences by maximizing the PLL through iterative sampling and residue replacement.

- Generate multiple design trajectories (typically 5 per backbone) to explore sequence diversity while maintaining structural compatibility.

Validation and Selection:

- Assess designed sequences using structural quality metrics including:

- Packing quality (core hydrophobic residues, void volumes)

- Hydrogen bonding satisfaction (buried unsatisfied donors/acceptors)

- Secondary structure propensity (agreement with predicted secondary structure)

- Rotamer recovery statistics compared to native structures

- Select top designs for experimental characterization based on these quality metrics.

- Assess designed sequences using structural quality metrics including:

Table 2: Performance Metrics of Learned Potential Design on Test Cases

| Metric | All Alpha | Alpha-Beta | All Beta | Core Regions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Native Rotamer Recovery | 72.6% | 70.8% | 74.1% | 90.0% |

| Native Sequence Recovery | 25-45% | 28-42% | 26-44% | 45-60% |

| Secondary Structure Prediction Accuracy | Comparable to native | Comparable to native | Comparable to native | Comparable to native |

| Buried Unsatisfied H-Bonds | Matches native | Matches native | Matches native | Matches native |

Workflow Visualization

De Novo Protein Design

RFdiffusion for De Novo Structure Generation

De novo protein design seeks to generate proteins with specified structural and functional properties that are not based on existing natural templates. The RFdiffusion method represents a breakthrough in this area by adapting the RoseTTAFold structure prediction network for protein structure denoising tasks, creating a generative model of protein backbones that achieves outstanding performance on de novo protein monomer design, protein binder design, symmetric oligomer design, and functional site scaffolding [6]. Unlike previous approaches that struggled with generating realistic and designable protein backbones, RFdiffusion employs a diffusion model framework that progressively builds protein structures through iterative denoising steps. Starting from random noise, the method generates elaborate protein structures with minimal overall structural similarity to proteins in the training set, demonstrating considerable generalization beyond the PDB [6]. This approach has enabled the creation of diverse alpha, beta, and mixed alpha-beta topologies with high experimental success rates.

Protocol: De Novo Backbone Generation with RFdiffusion

Objective: Generate novel protein backbone structures conditioned on functional specifications using diffusion-based generative modeling.

Materials and Software Requirements:

- RFdiffusion software (available from public repositories)

- ProteinMPNN for sequence design [6]

- AlphaFold2 or RoseTTAFold for in silico validation

- Computational resources: High-performance GPU cluster recommended

- Conditioning information (as needed): Partial structures, symmetry constraints, functional motifs

Methodology:

Model Initialization and Conditioning:

- Initialize random residue frames (Cα coordinates and N-Cα-C orientations) for the target protein length.

- Provide conditioning information based on design objectives:

- For unconditional generation: No additional conditioning

- For symmetric oligomers: Symmetry operators and interface specifications

- For functional sites: Fixed coordinates of active site residues or binding motifs

- For binder design: Target protein surface for interface conditioning

Iterative Denoising Process:

- For each diffusion step (up to 200 steps):

- RFdiffusion makes a denoised prediction of the protein structure from the noised input.

- Update each residue frame by taking a step toward the prediction with controlled noise addition.

- For conditional generation, apply constraints to maintain desired features throughout the process.

- Employ self-conditioning where the model conditions on previous predictions between timesteps, improving coherence and performance.

- For each diffusion step (up to 200 steps):

Backbone Selection and Validation:

- Generate multiple backbone candidates (typically 100-1000) through independent denoising trajectories.

- Filter backbones based on structural metrics (compactness, secondary structure content, packing quality).

- Validate backbones using structure prediction networks (AlphaFold2 or ESMFold):

- Process: Input designed sequences from ProteinMPNN into structure predictor

- Success criteria: High confidence (pAE < 5) and low RMSD (< 2Ã… global, < 1Ã… on functional sites) to design model

Sequence Design and Experimental Characterization:

- Use ProteinMPNN to design sequences for validated backbones, typically sampling 8 sequences per design.

- Screen designs in silico using structural validation metrics.

- Select top candidates for experimental testing (cryo-EM, X-ray crystallography, functional assays).

Table 3: RFdiffusion Performance on Diverse Design Challenges

| Design Challenge | Success Rate | Key Metrics | Experimental Validation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Unconditional Monomer Design | High | AF2/ESMFold confidence, structural diversity | 6/6 characterized designs had correct structures |

| Symmetric Oligomers | High | Interface geometry, symmetry accuracy | Hundreds of symmetric assemblies characterized |

| Protein Binder Design | High | Interface complementarity, binding affinity | cryo-EM structure nearly identical to design model |

| Active Site Scaffolding | Moderate-High | Functional geometry preservation, stability | Metal-binding proteins and enzymes validated |

Protocol: Requirement-Driven Design with SEWING

Objective: Create novel protein structures that satisfy user-defined functional requirements by assembling fragments of naturally occurring proteins.

Materials and Software Requirements:

- Rosetta software with SEWING module (license required for academic use)

- Database of structural fragments from native proteins

- Cluster computing resources for large-scale sampling

- Custom RosettaScripts for specific design requirements

Methodology:

Requirement Specification and Starting Structure Selection:

- Define structural or functional requirements (e.g., binding pocket geometry, interface characteristics, metal coordination site).

- Select a starting substructure from the fragment database that contains some required features, or begin with a random fragment.

Monte Carlo Assembly Process:

- Perform Monte Carlo simulation with the following moves:

- Addition: Add a compatible substructure to a growing terminus (probability: 0.05-0.1)

- Deletion: Remove a substructure from a terminus (probability: 0.005-0.01)

- Switch: Replace a terminal substructure with an alternative (probability: balance)

- Use temperature cooling from starttemperature to endtemperature over min_cycles (typically 10,000 cycles).

- Continue assembly until requirements are satisfied or max_cycles (typically 20,000) is reached.

- Perform Monte Carlo simulation with the following moves:

Requirement Enforcement During Assembly:

- Incorporate custom score terms and filters to bias assembly toward requirement satisfaction.

- For ligand binding sites: Include geometric constraints for optimal ligand coordination.

- For protein interfaces: Enforce surface compatibility and interaction potential.

- For metal binding: Incorporate coordination geometry preferences.

Structure Selection and Refinement:

- Generate large assembly sets (>10,000 structures) and select top 10% by SEWING score.

- Perform rotamer-based sequence optimization using Rosetta's fixed-backbone design protocols.

- Refine selected designs with backbone flexibility to relieve clashes and improve packing.

- Filter final designs using quality metrics (packing statistics, hydrogen bonding, residue burial).

Workflow Visualization

Table 4: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Protein Design

| Resource Name | Type | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| RFdiffusion | Software | De novo protein backbone generation | Creating novel protein folds and functional sites |

| RoseTTAFold | Software | Protein structure prediction | Validating designed structures and sequences |

| AlphaFold2 | Software | Protein structure prediction | In silico validation of design models |

| ProteinMPNN | Software | Protein sequence design | Optimizing sequences for fixed backbone structures |

| Rosetta SEWING | Software | Requirement-driven backbone assembly | Designing proteins with specific functional features |

| TASSER(VMT) | Software | Template-based structure modeling | Comparative modeling with multiple templates |

| 1-Step Human Coupled IVT Kit | Wet-bench reagent | In vitro protein expression | Rapid testing of designed proteins without cloning |

| CATH Database | Database | Protein structure classification | Template identification and fold analysis |

| PDB | Database | Experimental protein structures | Source of templates and fragment libraries |

The three core paradigms of computational protein design—template-based modeling, sequence optimization, and de novo design—provide complementary approaches for creating proteins with desired structures and functions. Template-based methods leverage evolutionary information to build reliable models, sequence optimization solves the inverse folding problem to stabilize designed structures, and de novo approaches enable the creation of entirely novel proteins not found in nature. The integration of artificial intelligence and machine learning across all three paradigms is dramatically accelerating the field, moving protein design from modification of natural proteins to the creation of custom biomolecules with tailor-made functions. As these methods continue to mature and integrate with experimental validation, they promise to unlock new possibilities in therapeutic development, synthetic biology, and biomaterials engineering, fundamentally expanding our ability to harness the protein functional universe for human benefit.

The field of computational protein design has undergone a revolutionary transformation through the integration of artificial intelligence, enabling researchers to predict and generate protein structures with unprecedented accuracy. This paradigm shift, catalyzed by DeepMind's AlphaFold system which effectively resolved the long-standing challenge of predicting a protein's 3D structure from its amino acid sequence, has created new frontiers in protein engineering and therapeutic development [7] [8]. The subsequent development of generative AI systems like RFdiffusion and sequence design tools like ProteinMPNN has established a comprehensive framework for de novo protein design, moving beyond prediction to creation of novel proteins with specified structural and functional properties [6] [9]. These technologies are significantly reshaping the landscape of drug discovery and development by enhancing the precision and speed at which drug targets are identified and drug candidates are designed and optimized [7]. Within the context of in silico validation computational protein assessment research, these tools provide robust platforms for generating and evaluating protein designs before experimental characterization, accelerating the entire protein engineering pipeline.

The integration of these systems has established a powerful workflow: RFdiffusion generates novel protein backbones conditioned on specific functional requirements, ProteinMPNN designs optimal sequences for these structural scaffolds, and AlphaFold provides critical validation of the resulting designs [6] [9]. This closed-loop design-validate cycle enables researchers to rapidly iterate and refine protein constructs computationally, significantly reducing the traditional reliance on expensive and time-consuming experimental screening. For research scientists and drug development professionals, understanding the capabilities, applications, and implementation requirements of these tools is essential for leveraging their full potential in therapeutic development, enzyme engineering, and basic biological research.

Table 1: Key AI Technologies in Protein Design

| Technology | Primary Function | Methodology | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| AlphaFold | Protein structure prediction | Deep learning with Evoformer architecture & structural modules | Predicting 3D structures from amino acid sequences [10] [8] |

| RFdiffusion | Protein structure generation | Diffusion model fine-tuned on RoseTTAFold structure prediction network | De novo protein design, motif scaffolding, binder design [6] [11] |

| ProteinMPNN | Protein sequence design | Message passing neural network with backbone conditioning | Sequence design for structural scaffolds, robust sequence recovery [9] |

| OpenFold3 | Open-source structure prediction | AlphaFold-inspired architecture | Academic alternative to AlphaFold with comparable performance [12] |

The core AI systems revolutionizing protein design employ complementary approaches that address different aspects of the protein design challenge. AlphaFold represents a breakthrough in structure prediction, utilizing a deep learning architecture that combines attention-based transformers with structural modeling to achieve accuracy competitive with experimental methods [10] [8]. The system has been made accessible through the AlphaFold Protein Structure Database, which provides open access to over 200 million protein structure predictions, dramatically expanding the structural coverage of known proteomes [10].

RFdiffusion builds upon this structural understanding by implementing a generative diffusion model that creates novel protein structures through a progressive denoising process [6] [11]. By fine-tuning the RoseTTAFold structure prediction network on protein structure denoising tasks, RFdiffusion obtains a generative model of protein backbones that achieves outstanding performance on unconditional and topology-constrained protein monomer design, protein binder design, symmetric oligomer design, and enzyme active site scaffolding [6]. The method demonstrates considerable generalization beyond structures seen during training, generating elaborate protein structures with little overall structural similarity to those in the Protein Data Bank [6].

ProteinMPNN addresses the inverse problem of designing amino acid sequences that fold into desired protein structures [9]. This deep learning-based protein sequence design method employs a message passing neural network architecture that takes protein backbone features—including distances between atoms and backbone dihedral angles—as input to predict optimal amino acid sequences. Unlike physically-based approaches like Rosetta, ProteinMPNN achieves significantly higher sequence recovery (52.4% versus 32.9% for Rosetta) while requiring only a fraction of the computational time [9].

Figure 1: Integrated AI Protein Design Workflow

Application Notes: Research Implementation Protocols

Protocol 1: De Novo Protein Monomer Design

Objective: Generate novel protein monomers with specified structural properties using RFdiffusion and ProteinMPNN.

Materials and Equipment:

- RFdiffusion software (available via GitHub repository)

- ProteinMPNN package

- AlphaFold2 or ESMFold for validation

- High-performance computing system with GPU acceleration

- Python 3.8+ environment with required dependencies

Procedure:

Environment Setup: Clone the RFdiffusion repository and install dependencies following the installation guide. Download pre-trained model weights for base RFdiffusion models.

Unconditional Generation: Execute RFdiffusion with contig parameters specifying desired protein length range. Example command for generating 150-residue proteins:

Structure Refinement: Select generated backbones with favorable structural characteristics (compactness, secondary structure composition). Filter out designs with irregular geometries or poor packing.

Sequence Design: Process selected backbones with ProteinMPNN to generate amino acid sequences. Use default parameters for initial design, with temperature setting of 0.1 for focused sampling.

In silico Validation:

- Process designed sequences through AlphaFold2 or ESMFold to verify they fold into intended structures.

- Calculate metrics: predicted aligned error (pAE), pLDDT confidence score, and TM-score relative to design model.

- Consider designs successful when AF2 structure has mean pAE < 5 and backbone RMSD < 2Ã… to designed structure [6].

Experimental Characterization: Express top-ranking designs recombinantly, purify proteins, and assess folding via circular dichroism spectroscopy and thermal stability assays [6].

Protocol 2: Protein Binder Design

Objective: Design novel proteins that bind to specific target molecules of therapeutic interest.

Materials and Equipment:

- RFdiffusion with complex base checkpoint

- Target protein structure in PDB format

- ProteinMPNN with symmetry-aware capabilities

- Molecular docking software (optional)

Procedure:

Target Preparation: Obtain 3D structure of target protein. If experimental structure unavailable, use AlphaFold-predicted structure from AlphaFold Database.

Conditional Generation: Configure RFdiffusion for binder design by specifying the target chain and desired interface regions in the contig string. Example for designing a binder to chain A of a target:

Interface Optimization: Generate multiple design variants focusing on complementary surface geometry and favorable interfacial interactions (hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic complementarity).

Sequence Design with Interface Constraints: Use ProteinMPNN with chain-aware decoding to design sequences that optimize binding interactions while maintaining fold stability.

Binding Validation:

- Use AlphaFold Multimer to predict complex structure between designed binder and target.

- Assess interface quality using computational metrics like interface RMSD, buried surface area, and predicted binding energy.

- Perform molecular dynamics simulations to evaluate binding stability.

Experimental Validation: Express and purify binders, measure binding affinity via surface plasmon resonance or isothermal titration calorimetry, and determine complex structure via cryo-EM or X-ray crystallography if possible [6].

Table 2: Performance Metrics for AI Protein Design Tools

| Validation Metric | Threshold for Success | Assessment Method | Typical Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Structure Accuracy | RMSD < 2.0 Ã… | AlphaFold prediction vs design model | 90% of designs for monomers [6] |

| Sequence Recovery | >50% native sequence | ProteinMPNN on native backbones | 52.4% vs 32.9% for Rosetta [9] |

| Binding Affinity | Kd < 100 nM | Experimental measurement | Picomolar binders achieved [11] |

| Design Robustness | pLDDT > 80 | AlphaFold confidence score | Improved with noise training [9] |

Protocol 3: Motif Scaffolding for Functional Sites

Objective: Scaffold functional protein motifs (e.g., enzyme active sites, protein-protein interaction interfaces) into stable protein structures.

Procedure:

Motif Definition: Identify critical functional residues and their spatial arrangement from structural data or evolutionary conservation.

Conditional Generation: Use RFdiffusion motif scaffolding capability by specifying fixed motif positions and variable scaffold regions in contig string:

Scaffold Diversity: Generate multiple scaffold architectures with varying secondary structure compositions and topological arrangements.

Sequence Design with Functional Constraints: Fix functional residue identities during ProteinMPNN sequence design while optimizing surrounding sequence for stability.

Functional Validation:

- Verify preservation of functional site geometry through structural alignment.

- For enzymatic motifs, use computational docking to assess substrate binding.

- For protein interaction motifs, assess interface preservation.

Figure 2: Motif Scaffolding Workflow

Table 3: Essential Resources for AI-Driven Protein Design

| Resource | Type | Function | Access |

|---|---|---|---|

| AlphaFold DB | Database | Pre-computed structures for 200+ million proteins | https://alphafold.ebi.ac.uk [10] |

| RFdiffusion Models | Software | Conditional generation of protein structures | RosettaCommons GitHub [13] |

| ProteinMPNN | Software | Neural network for sequence design | Public GitHub repository [9] |

| ESM Metagenomic Atlas | Database | 700+ million predicted structures from metagenomic data | https://esmatlas.com [7] |

| Protein Data Bank | Database | Experimentally determined protein structures | https://www.rcsb.org [7] |

| SE(3)-Transformer | Library | Equivariant neural network backbone | Conda/Pip install [13] |

Validation Framework: Computational Assessment Protocols

In silico Validation Pipeline: Establishing robust computational validation is essential for assessing design quality before experimental investment. The following multi-tiered approach provides comprehensive assessment:

Structural Quality Assessment:

- Calculate structural metrics: Ramachandran outliers, rotamer outliers, and clash scores.

- Assess structural plausibility using MolProbity or similar tools.

- Verify design novelty through structural comparison to PDB using FoldSeek or Dali.

Folding Confidence Validation:

- Process designs through AlphaFold2 with multiple sequence alignments to assess confidence (pLDDT and pAE).

- Use ESMFold for rapid folding confidence estimates.

- Consider designs with pLDDT > 70 and pAE < 10 as high confidence.

Stability Assessment:

- Perform molecular dynamics simulations (50-100 ns) to assess structural stability.

- Calculate RMSD, RMSF, and secondary structure persistence over simulation trajectory.

- Use AMBER or CHARMM force fields for physics-based assessment.

Functional Site Preservation:

- For motif scaffolding, ensure functional residue geometry is maintained within RMSD < 1.0 Ã….

- Verify accessibility of active sites or binding interfaces.

- Assess conservation of catalytic triads or binding residues.

This validation framework enables researchers to triage designs computationally, focusing experimental efforts on the most promising candidates and significantly increasing success rates [6] [14]. The integration of these computational assessments creates a robust pipeline for in silico protein design evaluation that aligns with the broader thesis of computational protein assessment research.

Implementation Considerations and Limitations

While AI-powered protein design tools have demonstrated remarkable capabilities, researchers should be aware of several practical considerations and limitations. Current approaches face inherent limitations in capturing the full dynamic reality of proteins in their native biological environments, as machine learning methods are trained on experimentally determined structures that may not fully represent thermodynamic environments controlling protein conformation at functional sites [14]. Performance can vary across different protein classes, with particular challenges in designing large proteins (>600 residues) where in silico validation becomes less reliable as they are generally beyond the single sequence prediction capabilities of AF2 and ESMFold [6]. Additionally, the accuracy of functional site design may be limited by the training data representation of specific motifs.

Successful implementation requires significant computational resources, including GPU acceleration for both RFdiffusion and ProteinMPNN, with adequate RAM for sequence searching during alignment and structure prediction [13] [15]. Researchers should incorporate noise during training and inference to improve robustness, as ProteinMPNN models trained with Gaussian noise (std=0.02Ã…) showed improved sequence recovery on AlphaFold protein backbone models [9]. For therapeutic applications, particular attention should be paid to potential immunogenicity and aggregation propensity of designed sequences, requiring additional computational assessment beyond structural accuracy alone.

The field continues to evolve rapidly, with new developments such as OpenFold3 emerging as open-source alternatives that aim to match AlphaFold's performance while providing greater accessibility and customization for the research community [12]. By understanding both the capabilities and current limitations of these AI protein design systems, researchers can more effectively leverage them in protein engineering pipelines and contribute to their continued refinement.

Computational protein design (CPD) represents a disruptive force in biotechnology, establishing a paradigm for engineering proteins with novel functions and properties that are unbound by known structural templates and evolutionary constraints [16] [17]. The overall goal of CPD is to specify a desired function, design a structure to execute this function, and find an amino acid sequence that folds into this structure [18]. This process is fundamentally an in silico exercise in reverse protein folding. The workflow is inherently cyclical, relying on iterative design, simulation, and validation steps to achieve a final, experimentally validated protein. Advances in artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning have dramatically accelerated this field, enabling atom-level precision in the creation of synthetic proteins for applications ranging from therapeutic development to the creation of robust biomaterials [16] [19]. This document outlines the detailed workflow, protocols, and key reagents for conducting rigorous in silico validation within a computational protein assessment research framework.

Stage 1: Computational Design andIn SilicoModeling

Foundational Principles and Strategy

The design process begins with establishing a target protein backbone, which is typically an ideal combination of secondary structural elements like α-helices and β-strands [18]. The stability of this scaffold is a primary consideration, guided by the principle that native protein structures occupy the lowest free energy state [18]. Key stabilizing forces include the formation of a hydrophobic core, where non-polar residues are segregated from the solvent, and the optimization of hydrogen bonding networks, particularly within force-bearing β-sheets [18] [19].

Two predominant strategies are employed in this phase:

- Rational Design: This approach uses physical principles and energy functions to engineer proteins with specific topology and functional features [18].

- AI-Driven De Novo Design: This approach uses deep learning models to explore the entirety of possible sequence and structural space, generating proteins that are entirely novel and not based on natural templates [18] [16].

Key Algorithms and Tools for Design

The core of the design process involves identifying low-energy amino acid sequences for a given backbone through combinatorial rotamer optimization [18]. AI-based generative models have become central to this effort.

Table 1: Key Computational Tools for Protein Design and Sequence Optimization

| Tool Name | Function | Key Application |

|---|---|---|

| RFdiffusion [19] | De novo protein structure generation | Creates novel protein structures based on user-defined constraints. |

| ProteinMPNN [18] [19] | Protein sequence design | Rapidly generates amino acid sequences that fold into a given protein backbone. |

| LigandMPNN [18] | Protein sequence design | Specialized for designing protein sequences in the presence of ligands or other small molecules. |

| AlphaFold2 [20] [19] | Protein structure prediction | Validates that a designed sequence will fold into the intended structure. |

| AI2BMD [21] | Ab initio biomolecular dynamics | Simulates full-atom proteins with quantum chemistry accuracy to explore conformational space. |

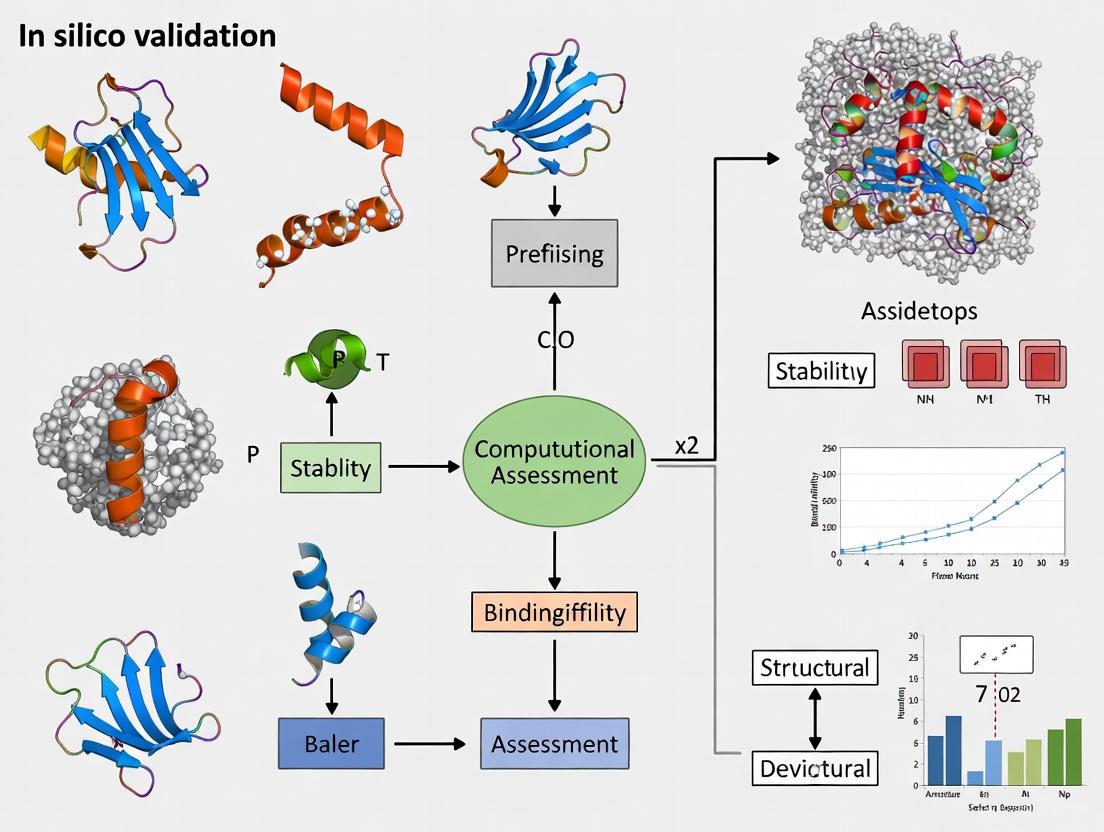

Workflow Visualization: Core Design and Validation Loop

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow of the computational design and initial validation process:

Stage 2:In SilicoValidation and Stability Assessment

Once a protein is designed, comprehensive computational validation is critical to prioritize designs for costly and time-consuming experimental synthesis. This stage assesses the designed protein's stability, dynamics, and functional properties.

Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulation Protocols

MD simulations serve as a "computational microscope" to observe protein behavior over time [21]. They are essential for probing conformational stability, folding pathways, and flexibility.

Protocol 3.1.1: Equilibrium Molecular Dynamics Simulation

This protocol is used to assess the structural stability and flexibility of a designed protein under simulated physiological conditions.

System Preparation:

- Obtain the initial atomistic coordinates from the design stage (e.g., from RFdiffusion or AlphaFold2 prediction).

- Solvate the protein in an explicit water box (e.g., TIP3P water model), ensuring a minimum distance of 1.0 nm between the protein and box edges.

- Add ions (e.g., Naâº, Clâ») to neutralize the system's charge and simulate a desired physiological salt concentration (e.g., 150 mM NaCl).

Energy Minimization:

- Use a steepest descent algorithm to minimize the energy of the solvated system, relieving any steric clashes. Run until the maximum force is below a threshold (e.g., 1000 kJ/mol/nm).

System Equilibration:

- Perform equilibration in two phases under NVT (constant Number of particles, Volume, and Temperature) and NPT (constant Number of particles, Pressure, and Temperature) ensembles.

- NVT Equilibration: Run for 100 ps while restraining protein heavy atoms, gradually heating the system to the target temperature (e.g., 310 K using a thermostat like Nosé-Hoover).

- NPT Equilibration: Run for 100 ps with restrained protein heavy atoms, coupling the system to a barostat (e.g., Parrinello-Rahman) to achieve the target pressure (e.g., 1 bar).

Production MD Run:

- Run an unrestrained simulation for a duration sufficient to observe relevant dynamics. For initial stability checks, 100 ns to 1 µs is typical. Use a time step of 2 fs.

- For ab initio accuracy, consider using AI-based MD systems like AI2BMD, which can simulate thousands of atoms with density functional theory (DFT)-level accuracy but are several orders of magnitude faster than conventional DFT [21].

Analysis:

- Calculate the root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) of the protein backbone to measure structural stability.

- Calculate the root-mean-square fluctuation (RMSF) of residues to identify flexible regions.

- Analyze the radius of gyration (Rg) to monitor compactness.

- Monitor the number and lifetime of intramolecular hydrogen bonds, a key metric for mechanical stability [19].

Protocol 3.1.2: Steered Molecular Dynamics (SMD) for Mechanical Strength

This protocol is used to quantitatively assess the mechanical unfolding resistance of a designed protein, which is particularly relevant for materials science applications [19].

- System Setup: Follow the steps in Protocol 3.1.1 for system preparation, energy minimization, and equilibration.

- Applying Force: Fix the C-terminal atom of the protein and apply a constant pulling force or a constant velocity to the N-terminal atom.

- Simulation Run: Run the simulation while the protein unfolds under the applied mechanical stress. Record the force and extension over time.

- Data Analysis: Plot a force-extension curve. The peak force observed before a major unfolding event is the unfolding force. Designs with maximized hydrogen-bond networks have demonstrated unfolding forces exceeding 1000 pN, about 400% stronger than natural titin domains [19].

AI-Based Ensemble and Trajectory Prediction

Static structures are insufficient to capture protein function. AI models are now being developed to predict the ensemble of conformations a protein can adopt, providing a more holistic view of dynamics [20].

Table 2: Computational Methods for Stability and Ensemble Validation

| Validation Method | Measured Property | Interpretation of Results |

|---|---|---|

| Equilibrium MD [21] | Root-mean-square deviation (RMSD), Radius of Gyration (Rg) | Low backbone RMSD (<0.2-0.3 nm) and stable Rg indicate a stable, folded design. |

| Steered MD [19] | Unfolding Force (picoNewtons, pN) | Higher forces indicate greater mechanical stability. >1000 pN is considered superstable. |

| Generative Models (e.g., AlphaFlow, DiG) [20] | Conformational Diversity & Root-mean-square fluctuation (RMSF) | Recovers flexible regions and alternative states; validates against experimental NMR data. |

| AI2BMD Folding/Unfolding [21] | Free Energy of Folding (ΔG) | A negative ΔG indicates a stable fold. Provides thermodynamic properties aligned with experiments. |

Advanced Workflow: Incorporating Ensemble Modeling

For a more thorough assessment, the core validation workflow can be enhanced with specialized ensemble and stability checks, as shown below:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Computational Solutions

The following table details essential computational "reagents" – software, databases, and resources – required for executing the workflows described in this document.

Table 3: Essential Computational Reagents for Protein Design and Validation

| Resource Category & Name | Function in Workflow | Access Information |

|---|---|---|

| Design & Sequence Tools | ||

| ProteinMPNN [18] | Fast, robust protein sequence design for a fixed backbone. | Publicly available code repositories. |

| RFdiffusion [19] | De novo generation of novel protein structures from noise. | Publicly available code repositories. |

| Structure Prediction | ||

| AlphaFold2 [20] | Highly accurate protein structure prediction from sequence. | Publicly available; accessed via local installation or web APIs. |

| Simulation & Dynamics | ||

| AI2BMD [21] | Ab initio accuracy MD for large biomolecules; enables precise free-energy calculations. | Methodology described in literature; code availability may vary. |

| GROMACS [19] | High-performance classical MD simulation package. | Open-source software. |

| Data & Validation Resources | ||

| Protein Data Bank (PDB) [22] | Repository of experimentally determined 3D structures of proteins; used for training and validation. | Publicly accessible database (rcsb.org). |

| UniProt [22] | Comprehensive protein sequence and functional information. | Publicly accessible database (uniprot.org). |

| ATLAS / mdCATH [20] | Curated datasets of molecular dynamics trajectories; used for training and benchmarking ensemble models. | Publicly available datasets. |

| MS-Peg10-thp | MS-Peg10-thp, MF:C26H52O14S, MW:620.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Amicoumacin B | Amicoumacin B, MF:C20H30N2O9, MW:442.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The integrated workflow of computational design, robust in silico validation, and experimental synthesis forms a powerful cycle for creating novel proteins with tailored functions. The protocols and tools outlined here provide a framework for researchers to rigorously assess the stability, dynamics, and functional potential of designed proteins before moving to the bench. As AI models for predicting ensemble properties and high-accuracy molecular dynamics simulations continue to mature, the reliability and precision of in silico validation will only increase, further accelerating the design-build-test cycle in synthetic biology and biotechnology.

Methodologies and Real-World Applications in Therapeutics and Engineering

The rapid expansion of protein sequence data has created a critical gap between known sequences and experimentally determined structures and functions. In silico computational methods have emerged as indispensable tools for bridging this gap, enabling researchers to predict protein properties, interactions, and functions with increasing accuracy. Among these methods, three deep learning architectures have demonstrated particular promise: Graph Neural Networks (GNNs), Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), and Transformer models. This article provides application notes and protocols for implementing these architectures within computational protein assessment research, framed specifically for drug development and protein engineering applications.

Architectural Foundations & Applications

Transformer Architectures in Protein Informatics

Transformer architectures, originally developed for natural language processing, have been successfully adapted for protein research due to their ability to process variable-length sequences and capture long-range dependencies through self-attention mechanisms [23]. The core innovation lies in the self-attention mechanism, which dynamically models pairwise relevance between elements in a protein sequence to explicitly capture intrasequence dependencies [23].

For protein sequences, the self-attention mechanism operates by defining three learnable weight matrices (Query, Key, and Value) that project input sequences into feature representations. The output is computed as a weighted sum of value vectors, with weights determined by compatibility between query and key vectors [23]. This architecture enables the model to learn complex relationships between amino acids that may be distant in the primary sequence but proximal in the folded structure.

Transformers have revolutionized multiple domains in protein science, including:

- Protein Structure Prediction: Models like ESMFold demonstrate near-experimental accuracy in predicting 3D structures from amino acid sequences [24] [25]

- Function Prediction: Self-supervised pre-training on large protein sequence databases enables accurate functional annotation without explicit supervision [23]

- Protein-Protein Interactions: Transformer-based models can predict interaction partners and binding affinities from sequence data alone [23]

Graph Neural Networks for Structure-Based Prediction

GNNs operate on graph-structured data, making them ideally suited for analyzing protein structures and interaction networks. In these representations, nodes typically correspond to amino acid residues or atoms, while edges represent spatial relationships or chemical bonds [26]. GNNs leverage message-passing algorithms to propagate information across the graph, enabling them to capture complex topological features essential for understanding protein function.

Key applications of GNNs in protein science include:

- Protein Function Prediction: GNNs learn representations from protein graphs at various granularity levels (atomic, residue, multi-scale) to predict Gene Ontology terms and interaction profiles [26]

- Protein-Protein Interaction Prediction: By modeling structural complexes as graphs, GNNs can predict binding interfaces and interaction strengths [26]

- Functional Annotation: GNN architectures leverage structural knowledge to improve the quality of protein function predictions beyond sequence-based methods [26]

Convolutional Neural Networks for Sequence-Pattern Recognition

CNNs employ hierarchical layers of filters that scan local regions of input data to detect spatially-localized patterns. For protein sequences, 1D-CNNs effectively identify conserved motifs, domain architectures, and sequence features that influence structure and function [27] [28].

Protocol implementations demonstrate CNNs applied to:

- Protein-Protein Interaction Prediction: Deep_PPI uses dual convolutional heads to process individual proteins before predicting interactions through fully connected layers [27]

- Protein Abundance Prediction: CNNs predict protein concentrations from mRNA levels by learning regulatory sequence motifs in untranslated and coding regions [28]

- Feature Extraction: Filter layers automatically detect biologically relevant patterns without manual feature engineering [28]

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Deep Learning Architectures on Key Protein Tasks

| Architecture | Application | Performance Metric | Value | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transformer (ESMFold) | Structure Prediction | Accuracy (Relative to Experimental) | Near-experimental | [24] [25] |

| 1D-CNN (Deep_PPI) | PPI Prediction (H. sapiens) | Accuracy | Superior to ML baselines | [27] |

| CNN | Protein Abundance Prediction (H. sapiens) | Coefficient of Determination (r²) | 0.30 | [28] |

| CNN | Protein Abundance Prediction (A. thaliana) | Coefficient of Determination (r²) | 0.32 | [28] |

| GNN | Gene Ontology Prediction | Quality Improvement | Promising | [26] |

Application Notes & Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Predicting Protein-Protein Interactions with Deep_PPI CNN

Objective: Predict binary protein-protein interactions from sequence information alone using a dual-branch convolutional neural network.

Materials:

- Protein sequences in FASTA format

- Known PPI pairs (positive and negative examples)

- Python 3.8+ with TensorFlow 2.8+ and Keras

- Hardware: GPU recommended for training

Methodology:

- Data Preparation:

- Curate balanced datasets of positive and negative interaction pairs

- Remove sequences with abnormal amino acids (B, J, O, U, X, Z)

- Filter out sequences shorter than 50 amino acids

- Apply PaddVal strategy to equalize sequence lengths (set to 90th percentile length)

Feature Engineering:

- Represent 20 native amino acids plus one special character using integers 1-21

- Apply one-hot encoding via Keras

one_hotfunction - Implement binary profile encoding with PaddVal strategy

- Generate 21-dimensional feature vectors for each residue position

Model Architecture:

- Implement two parallel 1D-CNN branches for each protein in a pair

- Each branch contains convolutional layers with ReLU activation

- Combine outputs from both branches via concatenation

- Add fully connected layers with decreasing dimensionality

- Final sigmoid activation for binary classification

Training Protocol:

- Initialize with He normal weight initialization

- Use Adam optimizer with learning rate 0.001

- Implement batch normalization between layers

- Apply five-fold cross-validation

- Monitor validation loss for early stopping

Validation:

- Evaluate on independent test sets for multiple species

- Compare against traditional machine learning baselines

- Assess generalization across organisms [27]

Protocol: Structure-Informed Function Prediction with GNNs

Objective: Predict protein function (Gene Ontology terms) from structural representations using graph neural networks.

Materials:

- Protein structures (PDB files or predicted structures)

- Gene Ontology annotations

- PyTorch Geometric or Deep Graph Library

- Hardware: GPU with ≥8GB memory

Methodology:

- Graph Construction:

- Represent proteins as graphs at atomic, residue, or multi-scale levels

- Nodes: amino acid residues with feature vectors (amino acid type, physicochemical properties)

- Edges: Spatial proximity (distance cutoffs 4-8Ã…) or chemical bonds

- Incorporate hierarchical relationships for multi-scale graphs

GNN Architecture Selection:

- Graph Attention Networks for weighted neighbor contributions

- Message Passing Neural Networks for information propagation

- Graph Convolutional Networks for hierarchical feature extraction

Model Implementation:

- Implement 3-6 graph convolution layers with skip connections

- Apply global pooling (attention-based or mean) for graph-level embeddings

- Add multi-layer perceptron head for GO term prediction

- Use multi-label loss function for simultaneous term prediction

Training Protocol:

- Use Adam optimizer with learning rate 0.001

- Implement class balancing for rare GO terms

- Apply gradient clipping to prevent explosion

- Regularize with dropout (0.2-0.5) between layers

Interpretation:

- Analyze attention weights to identify functionally important residues

- Visualize node contributions to predictions

- Map important regions to protein structures [26]

Protocol: Protein Abundance Prediction from Sequence with CNN

Objective: Predict protein abundance from mRNA expression levels and sequence features using a multi-input convolutional neural network.

Materials:

- Matched transcriptome-proteome datasets (mRNA TPM/FPKM, protein iBAQ)

- Sequence data (5' UTR, 3' UTR, CDS, protein sequence)

- TensorFlow 2.8+ with custom NaN-safe MSE loss function

- Hardware: GPU acceleration recommended

Methodology:

- Data Preprocessing:

- Convert all transcript abundances to TPM units

- Apply log2 transformation to iBAQ values

- Filter genes with <21 matched data points for robust regression

- Reserve genes with exactly 20 points as hold-out test set

Sequence Encoding:

- Extract 5' UTR, 3' UTR, CDS, and protein sequences

- Apply one-hot encoding (4 for nucleotides, 20 for amino acids)

- Pad sequences to uniform length for batch processing

- Implement custom generators for multi-input architecture

Multi-Input Architecture:

- Implement separate convolutional branches for each sequence type

- Each branch: 16 filters, kernel size 8-12, tanh activation, ReLU, sum pooling

- Process codon counts, nucleotide counts through dense layers

- Combine all features through intermediate dense layers (32→16 units)

Output Formulation:

- Final dense layer with 2 filters plus bias (a, b in: log2(iBAQ) = a * log2(TPM) + b)

- Expand for additional input genes: (2 + n genes) outputs

- Implement custom loss function handling varying valid data points per gene

Training Protocol:

- Use stochastic gradient descent without momentum

- Set learning rates based on input features (1e-3 to 1e-4)

- Train for 256-512 epochs with batch size 32

- Implement five independent repeats with tenfold cross-validation [28]

Visualization of Computational Workflows

CNN Protein-Protein Interaction Prediction Workflow

CNN PPI Prediction Flow

GNN Protein Function Prediction Workflow

GNN Function Prediction Flow

Transformer Protein Structure Prediction Workflow

Transformer Structure Prediction

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Computational Tools and Databases for Protein Informatics

| Resource | Type | Application | Access |

|---|---|---|---|

| ESM-2 | Transformer Model | Protein Structure & Function Prediction | GitHub |

| Deep_PPI | CNN Model | Protein-Protein Interaction Prediction | Research Code [27] |

| PyTorch Geometric | GNN Library | Protein Graph Representation Learning | Open Source |

| Protein Data Bank (PDB) | Structure Database | Experimental Structures for Training/Validation | Public Repository [25] |

| Swiss-Prot | Protein Database | Annotated Protein Sequences & Functions | Public Repository [27] |

| Gene Ontology Database | Functional Annotation | Protein Function Prediction Ground Truth | Public Repository [26] [28] |

| TensorFlow 2.8+ | Deep Learning Framework | Model Implementation & Training | Open Source [28] |

| TIM-1/GastroPlus | Physiological Modeling | GI Digestion Simulation & Validation | Commercial [29] |

The computational design of antibodies represents a frontier in modern biologics discovery, offering the potential to create novel therapeutics with precise target specificity. However, the accurate prediction of Complementarity-Determining Region (CDR) loop structures, particularly the hypervariable CDR-H3 loop, remains a primary challenge that directly impacts the developability of antibody-based therapeutics [30] [31]. CDR loops form the antigen-binding site and are critical for determining both affinity and specificity, yet their structural diversity and conformational flexibility present significant obstacles for computational modeling [30]. Recent advances in artificial intelligence (AI) and deep learning have revolutionized the field of antibody structure prediction, with specialized tools now achieving remarkable accuracy in CDR loop modeling [31] [32]. These improvements are essential for reliable developability assessment, which predicts the likelihood that an antibody candidate can be successfully developed into a manufacturable, stable, and efficacious drug [33]. This application note examines the current computational strategies for addressing CDR loop challenges and provides detailed protocols for incorporating developability assessment into early-stage antibody design workflows.

The CDR Loop Prediction Challenge

Structural Complexities of CDR Loops

Antibody binding specificity is primarily determined by six CDR loops - three each on the heavy (H1, H2, H3) and light (L1, L2, L3) chains [30]. While the antibody framework remains largely conserved, the CDR loops exhibit extraordinary structural diversity, with the CDR-H3 loop demonstrating the greatest variability in length, sequence, and structure [30] [31]. Five of the six loops typically adopt canonical cluster folds based on length and sequence composition, but the CDR-H3 loop largely defies such classification, making it the most challenging to predict accurately [30]. This challenge is compounded by the influence of relative VH-VL interdomain orientation on CDR-H3 conformation, as this loop is positioned directly at the interface between heavy and light chains [30].

Recent benchmarking studies reveal that even state-of-the-art prediction methods struggle with CDR-H3 accuracy. In comprehensive evaluations using high-quality crystal structures, current methods achieved average heavy atom RMSD values of 3.6-4.4 Ã… for CDR-H3 loops, significantly higher than errors for framework regions [31] [32]. These inaccuracies have direct consequences for downstream applications, including erroneous antibody-antigen docking results and unreliable biophysical property predictions such as surface hydrophobicity [30].

Critical Structural Inaccuracies and Their Impact

Computationally generated antibody models frequently contain structural inaccuracies that adversely affect developability assessments. Common issues include:

- Incorrect cis-amide bonds in CDR loops

- Wrong stereochemistry (D-amino acids instead of L-amino acids)

- Severe atomic clashes and non-physical bond lengths

- Inaccurate sidechain packing, particularly in CDR-H3 loops [30]

These errors significantly impact surface property predictions. Studies demonstrate that models containing cis-amide bonds and D-amino acids in CDR loops yield substantially different surface hydrophobicity profiles compared to experimental structures, potentially misleading developability assessments [30]. Since hydrophobicity is a conformation-dependent property, even small sidechain rearrangements can expose otherwise buried hydrophobic groups, altering perceived developability risk [30].

Table 1: Common Structural Inaccuracies in Antibody Models and Their Impact

| Structural Issue | Frequency in Models | Impact on Developability Assessment |

|---|---|---|

| Cis-amide bonds in CDRs | Up to 240 across 137 models [30] | Alters backbone conformation, affecting surface property predictions |

| D-amino acids | Up to 300 across 137 models [30] | Incorrect sidechain packing, misleading hydrophobicity estimates |

| Atomic clashes | Varies by modeling tool [30] | Physical implausibility, requires extensive refinement |

| Inaccurate CDR-H3 conformations | RMSD >2 Ã… in challenging cases [30] | Incorrect antigen-binding site characterization |

Computational Advances in Antibody Structure Prediction

AI-Driven Structure Prediction Tools

Recent years have witnessed transformative advances in antibody structure prediction, largely driven by deep learning approaches:

AlphaFold2 and Derivatives: While general protein structure predictors like AlphaFold2 (AF2) demonstrate remarkable accuracy for overall antibody structures (TM-scores >0.9) [31] [32], they show limitations for CDR-H3 loops, particularly for longer loops with limited sequence homologs [31]. This prompted the development of antibody-specific implementations.

Specialized Antibody Predictors: Tools such as ABlooper, DeepAb, IgFold, and Immunebuilder incorporate antibody-specific architectural adaptations to improve CDR loop modeling [30]. These tools typically achieve similar or better quality than general methods for antibody structures [30].

H3-OPT: This recently developed toolkit combines AF2 with a pre-trained protein language model, specifically targeting CDR-H3 accuracy [31] [32]. H3-OPT achieves a 2.24 Ã… average RMSD for CDR-H3 loops, outperforming other methods, particularly for challenging long loops [31]. The method employs a template module for high-confidence predictions and a PLM-based structure prediction module for difficult cases [34].

RFdiffusion for De Novo Design: Fine-tuned versions of RFdiffusion enable atomically accurate de novo design of antibodies by specifying target epitopes while maintaining stable framework regions [35]. This approach represents a paradigm shift from optimization to genuine de novo generation of epitope-specific binders.

Flow Matching for Antibody Design

FlowDesign represents an innovative approach that addresses limitations in current diffusion-based antibody design models [36]. By treating CDR design as a transport mapping problem, FlowDesign learns direct mapping from prior distributions to the target distribution, offering several advantages:

- Flexible prior distribution selection enabling integration of diverse knowledge

- Direct discrete distribution matching avoiding non-smooth generative processes

- High computational efficiency facilitating large-scale sampling [36]

In application to HIV-1 antibody design, FlowDesign successfully generated CDR-H3 variants with comparable or improved binding affinity and neutralization compared to the state-of-the-art HIV antibody ibalizumab [36].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Antibody Structure Prediction Tools

| Tool | Methodology | CDR-H3 Accuracy (RMSD) | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AlphaFold2 [31] | Deep learning with MSA | 3.79-3.92 Ã… [31] | High overall accuracy, excellent framework prediction | Limited CDR-H3 accuracy for long loops |

| ABlooper [30] | Antibody-specific deep learning | Similar to AF2 [30] | Fast prediction, antibody-optimized | May introduce structural inaccuracies |

| IgFold [31] | PLM-based | Comparable to AF2 [31] | Rapid prediction (seconds), high-throughput | Lower accuracy when templates available |

| H3-OPT [31] | AF2 + PLM | 2.24 Ã… (average) [31] | Superior CDR-H3 accuracy, template integration | Complex workflow, computational cost |

| RFdiffusion [35] | Diffusion-based de novo design | Atomic accuracy validated [35] | De novo design capability, epitope targeting | Requires experimental validation |

Experimental Protocols for Computational Developability Assessment

Protocol 1: Model Quality Validation with TopModel

Purpose: To identify and quantify structural inaccuracies in predicted antibody models that may affect developability assessments.

Materials:

- Predicted antibody 3D structures (PDB format)

- TopModel tool (https://github.com/liedllab/TopModel)

- PyMOL or similar visualization software [30]

Procedure:

- Input Preparation: Generate antibody structure models using preferred prediction tool(s). Save in PDB format.

- TopModel Analysis:

- Execute TopModel validation on each structure file

- Record counts of cis-amide bonds, D-amino acids, and atomic clashes

- Generate visualization output highlighting problematic regions

- Quality Assessment:

- Accept models with 0 D-amino acids and minimal cis-amide bonds (except cis-prolines)

- Flag models with severe clashes (>10% residues involved) for refinement

- Prioritize models passing all quality checks for further analysis

- Iterative Refinement: For failed models, consider alternative prediction tools or manual refinement of problematic regions.

Expected Results: Quality models should contain no D-amino acids, minimal non-proline cis-amide bonds, and fewer than 5% of residues involved in atomic clashes [30].

Protocol 2: Developability Assessment Using Therapeutic Antibody Profiler (TAP)

Purpose: To evaluate developability risk of antibody candidates based on surface physicochemical properties relative to clinical-stage therapeutics.

Materials:

- Antibody Fv sequences (VH and VL)

- ABodyBuilder2 for structure prediction (https://opig.stats.ox.ac.uk/webapps/abodybuilder2/)

- TAP implementation (https://github.com/oxpig/TAP)

- Reference dataset of clinical-stage therapeutic antibodies [37]

Procedure:

- Structure Modeling:

- Input VH and VL sequences into ABodyBuilder2

- Generate 3D structures for all candidates

- Validate model quality using Protocol 1

- TAP Analysis:

- Calculate five key developability metrics:

- Total CDR Length (Ltot)

- Patches of Surface Hydrophobicity (PSH)

- Positive Charge Patches (PPC)

- Negative Charge Patches (PNC)

- Spatial Aggregation Propensity (SAP)

- Compare metrics to distributions from clinical-stage therapeutics

- Calculate five key developability metrics:

- Risk Categorization:

- Assign "amber flags" to scores in 0th-5th or 95th-100th percentiles

- Assign "red flags" to scores beyond clinical-stage therapeutic ranges

- Calculate overall developability score for prioritization

- Visualization: Generate 3D surface representations colored by hydrophobicity/charge to identify problematic regions.

Expected Results: Developable candidates should show TAP metrics within the range of clinical-stage therapeutics, with minimal amber/red flags [37].

Figure 1: Computational Developability Assessment Workflow. This protocol integrates structure prediction, quality validation, and developability assessment in an iterative pipeline.

Protocol 3: De Novo Antibody Design with RFdiffusion

Purpose: To generate novel antibody binders targeting specific epitopes using diffusion-based generative models.

Materials:

- Target antigen structure (PDB format)

- Epitope specification (residue list)

- RFdiffusion implementation (https://github.com/RosettaCommons/RFdiffusion)

- ProteinMPNN for sequence design

- Fine-tuned RoseTTAFold2 for validation [35]

Procedure:

- Input Preparation:

- Prepare antigen structure with epitope residues specified

- Select antibody framework (e.g., humanized VHH for nanobodies)

- Define design regions (typically CDR loops)

- RFdiffusion Generation:

- Run fine-tuned RFdiffusion with epitope conditioning

- Generate 500-1000 backbone structures

- Filter based on interface quality and structural novelty

- Sequence Design with ProteinMPNN:

- Input selected backbones into ProteinMPNN

- Generate sequences optimized for stability and binding

- Filter sequences based on conservation and naturalness

- In Silico Validation:

- Use fine-tuned RoseTTAFold2 to predict complex structures

- Calculate interface metrics (ddG, buried surface area)

- Select top 50-100 designs for experimental testing

Expected Results: Initial designs typically exhibit modest affinity (tens to hundreds of nanomolar Kd), with potential for affinity maturation to single-digit nanomolar binders [35].

Table 3: Computational Tools for Antibody Design and Developability Assessment

| Tool Name | Type | Function | Access |

|---|---|---|---|

| TopModel [30] | Validation | Identifies structural inaccuracies (cis-amides, D-amino acids, clashes) | GitHub: liedllab/TopModel |

| ABodyBuilder2 [37] | Structure Prediction | Deep learning-based antibody modeling | Web server/API |

| H3-OPT [31] | Structure Prediction | Optimizes CDR-H3 loop prediction accuracy | Available upon request |

| RFdiffusion [35] | De Novo Design | Generates novel antibody binders to specified epitopes | GitHub: RosettaCommons/RFdiffusion |

| Therapeutic Antibody Profiler (TAP) [37] | Developability Assessment | Evaluates biophysical properties against clinical-stage therapeutics | GitHub: oxpig/TAP |

| FlowDesign [36] | CDR Design | Flow matching-based sequence-structure co-design | GitHub |

| IgFold [31] | Structure Prediction | PLM-based rapid antibody folding | GitHub |

The integration of advanced computational methods for antibody structure prediction and developability assessment represents a paradigm shift in biologics design. While challenges remain—particularly in accurate CDR-H3 loop prediction and structural validation—recent advances in AI-driven approaches now enable more reliable in silico profiling of antibody candidates. The protocols outlined in this application note provide a framework for systematic computational assessment, helping researchers identify developability risks early in the discovery process. As these methods continue to evolve, they promise to accelerate the development of novel antibody therapeutics with optimized properties for specialized administration routes and clinical applications.

The development of novel protein-based therapeutics represents a paradigm shift in modern medicine, rivaling and often surpassing traditional small-molecule drugs in treating complex diseases [38]. As of 2023, protein-based drugs are projected to constitute half of the top ten selling pharmaceuticals, with a global market approaching $400 billion [38]. This transformative growth has been catalyzed by advanced computational methodologies that enable researchers to preemptively address key development challenges including protein stability, immunogenicity, target specificity, and pharmacokinetic profiles.

In silico validation has emerged as a cornerstone of computational protein assessment, providing a critical framework for evaluating therapeutic potential before costly experimental work begins. These computational approaches allow researchers to simulate protein behavior under physiological conditions, predict interaction patterns with biological targets, and optimize structural characteristics for enhanced therapeutic efficacy. By integrating computational predictions with experimental validation, drug development professionals can accelerate the transition from candidate identification to clinical application while reducing development costs and failure rates.

The following application note details specific protocols and methodologies for leveraging in silico tools in the design and development of protein therapeutics and enzymes, with particular emphasis on practical implementation for research scientists.

Computational Assessment Protocols for Protein Therapeutics

In Silico Protein Digestibility Assessment

Protein digestibility represents a critical parameter in therapeutic development, directly influencing bioavailability and potential immunogenicity. Computational models can predict gastrointestinal stability, identifying sequences prone to enzymatic cleavage.

Protocol: In Silico Proteolytic Susceptibility Analysis

Purpose: To predict sites of proteolytic cleavage in simulated gastric and intestinal environments.

Methodology:

- Input Preparation: Obtain protein sequence in FASTA format and 3D structure (if available) in PDB format.

- Enzyme Selection: Configure computational digestion parameters for key proteases: pepsin (pH 2.0), trypsin, chymotrypsin, and pancreatin.

- Cleavage Simulation: Execute predictive algorithm based on:

- Known protease cleavage specificities

- Protein structural accessibility (surface exposure)

- Local flexibility parameters

- Output Analysis: Identify cleavage sites and generate semi-quantitative digestibility scores.

- Validation Correlation: Compare predictions with in vitro digestibility data when available.

Computational Tools: PEPSIM, ExPASy PeptideCutter, BIOVIA Discovery Studio

| Parameter | Implementation | Output Metrics |

|---|---|---|

| Protease Specificity | Position-specific scoring matrices | Cleavage probability scores |

| Structural Accessibility | Solvent-accessible surface area calculation | Relative susceptibility (0-1 scale) |

| Local Flexibility | B-factor analysis from PDB or molecular dynamics | Root mean square fluctuation (RMSF) |

| Digestibility Score | Composite algorithm weighting multiple factors | Predicted half-life, stability classification |

Interpretation Guidelines: Sequences with >80% predicted digestibility within 60 minutes are considered highly digestible; those with <20% digestibility are classified as resistant and may require further investigation for potential immunogenicity concerns [29].

Structure-Function Optimization Through Computational Engineering

Rational design of protein therapeutics employs computational tools to enhance stability, activity, and pharmacokinetic properties while reducing immunogenicity.

Protocol: Site-Directed Mutagenesis for Stability Enhancement

Purpose: To identify and validate amino acid substitutions that improve thermodynamic stability and reduce aggregation propensity.

Methodology:

- Structural Analysis: Load 3D protein structure and identify:

- Under-packed hydrophobic clusters

- Unsatisfied hydrogen bond donors/acceptors

- Unpaired charged residues

- Flexible regions with high B-factors

- Mutation Prediction: Utilize stability prediction algorithms (FoldX, RosettaDDG) to calculate ΔΔG values for potential mutations.

- Aggregation Propensity: Apply aggregation prediction algorithms (TANGO, AGGRESCAN) to screen stabilizing mutations for reduced aggregation potential.

- Structural Validation: Perform in silico structural analysis to confirm mutations do not disrupt active site or binding interfaces.

| Stabilization Strategy | Computational Approach | Therapeutic Example |

|---|---|---|

| Surface Charge Enhancement | Coulombic surface potential calculation | Supercharged GFP variants [38] |

| Hydrophobic Core Optimization | RosettaDesign packing quality assessment | Engineered antibody domains [38] |

| Disulfide Bridge Engineering | MODIP disulfide bond prediction | Engineered cytokines [38] |

| Glycosylation Site Addition | NetNGlyc/NetOGlyc prediction | Hyperglycosylated erythropoietin [38] |

Enzymatic Activity Optimization Through Computational Design

For enzyme therapeutics, computational methods can optimize catalytic efficiency, substrate specificity, and reaction conditions.

Protocol: Enzyme Assay Optimization Using Design of Experiments (DoE)

Purpose: To efficiently identify optimal assay conditions for enzymatic characterization using computational experimental design.

Methodology:

- Factor Identification: Select critical parameters for optimization (buffer pH, ionic strength, substrate concentration, enzyme concentration, cofactors, temperature).

- Experimental Design: Implement fractional factorial design to screen multiple factors simultaneously.

- Response Surface Methodology: Model the relationship between factors and enzymatic activity.

- Condition Prediction: Identify optimal assay conditions from modeled response surface.

- Validation: Experimentally verify predicted optimal conditions.

Implementation Note: This DoE approach can reduce optimization time from >12 weeks (traditional one-factor-at-a-time) to under 3 days for identifying significant factors and optimal conditions [39].

Diagram 1: In silico protein assessment workflow for therapeutic development.