High-Throughput Screening of Protein Variant Libraries: Methods, Applications, and Data Analysis

This article provides a comprehensive overview of high-throughput screening (HTS) for protein variant libraries, a cornerstone technology in modern drug discovery and protein engineering.

High-Throughput Screening of Protein Variant Libraries: Methods, Applications, and Data Analysis

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of high-throughput screening (HTS) for protein variant libraries, a cornerstone technology in modern drug discovery and protein engineering. It covers foundational concepts, from the core principles of HTS and the construction of diverse variant libraries using methods like error-prone PCR and oligonucleotide synthesis. The piece delves into advanced methodological applications, including cell-based assays and deep mutational scanning, which links genotype to phenotype for functional analysis. It also addresses critical challenges such as data quality control, hit selection, and the management of false positives. Finally, the article offers a comparative analysis of emerging platforms and automation technologies, synthesizing key takeaways and future directions for researchers and drug development professionals aiming to harness HTS for probing protein function and developing new biotherapeutics.

Protein Variant Libraries and HTS: Core Concepts and Library Construction

High-Throughput Screening (HTS) represents a paradigm shift in scientific discovery, enabling the rapid experimental conduct of millions of chemical, genetic, or pharmacological tests [1]. This methodology has become indispensable in drug discovery and development, allowing researchers to swiftly identify active compounds, antibodies, or genes that modulate specific biomolecular pathways [1] [2]. The core principle of HTS involves leveraging robotics, specialized data processing software, liquid handling devices, and sensitive detectors to automate and miniaturize biological or chemical assays, thereby dramatically accelerating the pace of research [1] [3]. For researchers investigating protein variant libraries, HTS provides the technological foundation for systematically evaluating vast collections of protein mutants to identify variants with desired properties, forming a critical component of modern protein engineering pipelines.

The evolution of HTS capabilities has been remarkable. In the 1980s, screening facilities could typically process only 10-100 compounds per week [3]. Through technological advancements, modern Ultra-High-Throughput Screening (uHTS) systems can now test >100,000 compounds per day, with some systems capable of screening millions of compounds [1] [3]. This exponential increase in throughput has transformed early drug discovery and basic research, making it possible to scan enormous chemical and biological spaces in timeframes previously unimaginable.

Core Principles of High-Throughput Screening

Fundamental Components and Workflow

The implementation of HTS relies on several integrated technological components working in concert. At the physical level, the microtiter plate serves as the fundamental testing vessel, with standardized formats containing 96, 384, 1536, 3456, or even 6144 wells [1]. These plates are arranged in arrays that are multiples of the original 96-well format (8×12 with 9mm spacing) [1]. The screening process typically begins with assay plate preparation, where small amounts of liquid (often nanoliters) are transferred from carefully catalogued stock plates to create assay-specific plates [1].

The subsequent reaction observation phase involves incubating the biological entity of interest (proteins, cells, or tissues) with the test compounds [1]. After an appropriate incubation period, measurements are taken across all wells, either manually for complex phenotypic observations or, more commonly, using specialized automated analysis machines that can generate thousands of data points in minutes [1]. The final critical phase involves hit identification and confirmation, where compounds showing desired activity ("hits") are selected for follow-up assays to confirm and refine initial observations [1].

Key Methodological Considerations

A successful HTS campaign requires careful attention to experimental design and quality control. Assay robustness is paramount, requiring validation to ensure reproducibility, sensitivity, and pharmacological relevance [2]. HTS assays must be appropriate for miniaturization to reduce reagent consumption and suitable for automation [2]. Statistical quality control measures, including the Z-factor and Strictly Standardized Mean Difference (SSMD), help differentiate between positive controls and negative references, ensuring data quality [1].

For protein variant library screening, additional considerations include the development of reporter systems that can accurately reflect protein function or stability. The readout must be scalable, reproducible, and directly correlated with the biological property of interest, whether that be enzymatic activity, binding affinity, or protein stability.

Automation Systems in HTS

Robotic Integration and Workflow Automation

Automation forms the backbone of modern HTS, enabling the rapid, precise, and reproducible execution of screening campaigns. Integrated robotic systems typically consist of one or more robots that transport assay microplates between specialized stations for sample and reagent addition, mixing, incubation, and final readout or detection [1]. These systems can prepare, incubate, and analyze many plates simultaneously, dramatically accelerating data collection [1].

The benefits of automation in HTS are multifaceted. Increased speed and throughput allow researchers to test more compounds in less time, accelerating discovery timelines [4]. Improved accuracy and consistency minimize human error in repetitive pipetting and plate handling tasks, enhancing data reliability [4]. Automation also enables reduced operational costs by minimizing reagent consumption through miniaturization and reducing labor requirements [4]. Furthermore, it expands the scope for discovery by allowing researchers to screen more extensive libraries and ask broader research questions [4].

Liquid Handling Technologies

Advanced liquid handling systems represent a critical automation component, enabling precise transfer of nanoliter volumes essential for miniaturized HTS formats [4]. Non-contact dispensers can accurately dispense volumes as low as 4 nL, ensuring consistent delivery of even delicate samples [4]. These systems facilitate the creation of assay plates from stock collections and the addition of reagents to initiated biochemical or cellular reactions.

Table 1: Key Automation Components in HTS Workflows

| Component | Function | Impact on Screening |

|---|---|---|

| Integrated Robotic Systems | Transport plates between stations for processing | Enables continuous, parallel processing of multiple plates |

| Automated Liquid Handlers | Precise nanoliter dispensing of samples and reagents | Minimizes volumes, reduces costs, improves accuracy |

| Plate Handling Robots | Manage and track plates via barcodes | Reduces human error in plate management |

| High-Capacity Detectors | Rapid signal measurement from multiple plates | Accelerates data acquisition from thousands of wells |

| Data Processing Software | Automate data collection and initial analysis | Provides near-immediate insights into promising compounds |

Throughput Tiers: HTS vs. uHTS

Defining Characteristics and Capabilities

The distinction between HTS and uHTS is primarily defined by screening capacity, though the cutoff remains somewhat arbitrary [3]. Traditional HTS typically processes 10,000-100,000 compounds per day, while uHTS can screen hundreds of thousands to millions of compounds daily [1] [3] [2]. This dramatic increase became possible through automated plate-handling instrumentation and the replacement of radiolabeling assays with luminescence- and fluorescence-based screens [3].

The evolution of screening formats has progressed from 96-well plates (standard in early HTS) to 384-well, 1536-well, and even higher density formats [1] [5]. While 384-well plates currently represent the most pragmatic balance between ease of use and throughput benefit, 1536-well plates are increasingly used in uHTS applications [5]. Recent innovations include chip-based screening systems and micro-channel flow systems that eliminate traditional plates entirely [3].

Table 2: Comparison of HTS and uHTS Capabilities

| Attribute | HTS | uHTS | Technical Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Throughput (tests/day) | Up to 100,000 | 100,000 to >1,000,000 | Requires more advanced automation and faster detection systems |

| Common Plate Formats | 96-well, 384-well | 384-well, 1536-well, 3456-well | Higher density formats demand more precise liquid handling |

| Liquid Handling Volume | Microliter range | Nanoliter to sub-nanoliter range | Requires specialized non-contact dispensers |

| Reagent Consumption | Moderate | Minimal | Enables screening with scarce biological reagents |

| Complexity & Cost | Significant | Substantially greater | Requires greater infrastructure investment and specialized expertise |

Quantitative High-Throughput Screening (qHTS)

A significant advancement in screening methodology is Quantitative HTS (qHTS), which generates full concentration-response relationships for each compound in a library rather than single-point measurements [1] [6]. By profiling compounds across multiple concentrations, qHTS provides rich datasets including half-maximal effective concentration (EC50), maximal response, and Hill coefficient (nH) parameters [1]. This approach enables the assessment of nascent structure-activity relationships early in screening and results in lower false-positive and false-negative rates compared to traditional HTS [6].

For protein variant libraries, qHTS is particularly valuable as it reveals not just whether a mutation affects function, but how it alters protein activity across a range of conditions. This provides deeper insights into mutational effects that can guide further protein engineering efforts.

Experimental Protocols for Protein Variant Library Screening

Protocol 1: Identifying Stabilizing Chaperones for Misfolded Protein Variants

Purpose: To identify small-molecule chaperones that stabilize proper folding of destabilized protein variants and promote their cellular trafficking.

Background: This protocol adapts the approach successfully used to identify pharmacological chaperones for P23H rhodopsin, a misfolded opsin mutant associated with retinitis pigmentosa [7]. The method is applicable to various misfolded protein variants that exhibit impaired cellular trafficking.

Materials:

- Stable cell line expressing the protein variant fused to a small subunit of β-galactosidase (β-Gal)

- Membrane-associated peptide (e.g., PLC domain) fused to a large subunit of β-Gal

- Compound library (dissolved in DMSO)

- Cell culture reagents and microplates

- β-Gal assay substrate buffer (Gal Screen System)

Procedure:

- Cell Seeding: Plate stable cells in 384-well assay plates at optimized density (e.g., 5,000 cells/well) and incubate for 24 hours [7].

- Compound Treatment: Transfer nanoliter volumes of test compounds from stock plates to assay plates using automated liquid handling. Include controls (DMSO-only negative controls, known chaperone positive controls).

- Incubation: Incubate compound-treated cells for 16-24 hours to allow protein folding and trafficking.

- Detection: Add β-Gal assay substrate buffer and measure luminescence after reconstitution of β-Gal activity.

- Data Analysis: Normalize data to controls and identify hits that significantly increase luminescence signal compared to DMSO controls.

Quality Control: Ensure assay robustness with Z' factor >0.5 and signal-to-background ratio >3 [7].

Protocol 2: Screening for Enhanced Clearance of Misfolded Protein Variants

Purpose: To identify small molecules that enhance clearance of misfolded protein variants while preserving wild-type protein function.

Background: This protocol is based on the strategy used to identify compounds that promote clearance of misfolded P23H opsin while maintaining vision through the wild-type allele [7]. This approach is valuable for dominant-negative disorders where mutant protein clearance is therapeutic.

Materials:

- Stable cell line expressing the protein variant fused to Renilla luciferase (RLuc) reporter

- Compound library (dissolved in DMSO)

- Cell culture reagents and microplates

- RLuc assay substrate (e.g., ViviRen)

Procedure:

- Cell Seeding: Plate stable cells in 384-well assay plates at optimized density and incubate for 24 hours [7].

- Compound Treatment: Transfer test compounds to assay plates using automated liquid handling. Include controls (DMSO-only negative controls, known clearance enhancer positive controls).

- Incubation: Incubate compound-treated cells for 16-48 hours to allow protein degradation.

- Detection: Add RLuc assay substrate and measure luminescence signal.

- Data Analysis: Normalize data to controls and identify hits that significantly decrease luminescence signal compared to DMSO controls.

Quality Control: Monitor assay performance with Z' factor >0.5 throughout screening campaign [7].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for HTS of Protein Variant Libraries

| Reagent/Category | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Reporter Enzymes | Quantify protein levels, localization, or function | β-Galactosidase fragment complementation, Renilla luciferase, Firefly luciferase [7] |

| Specialized Cell Lines | Provide consistent biological context for screening | Stable cell lines expressing protein variant-reporter fusions [7] |

| Detection Reagents | Generate measurable signals from biological events | Gal Screen substrate, ViviRen luciferase substrate [7] |

| Compound Libraries | Source of potential modulators of protein function | Diversity Sets, targeted libraries, natural product collections [7] [2] |

| Automation-Compatible Plates | Miniaturized reaction vessels for HTS | 384-well, 1536-well microplates with optimal surface treatments [1] [5] |

| Liquid Handling Reagents | Enable precise nanoliter dispensing | DMSO-compatible buffers, non-fouling surfactants, viscosity modifiers [4] |

| Fmoc-NIP-OH | Fmoc-NIP-OH, CAS:158922-07-7, MF:C21H21NO4, MW:351.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Fmoc-Tle-OH | Fmoc-Tle-OH, CAS:132684-60-7, MF:C21H23NO4, MW:353.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

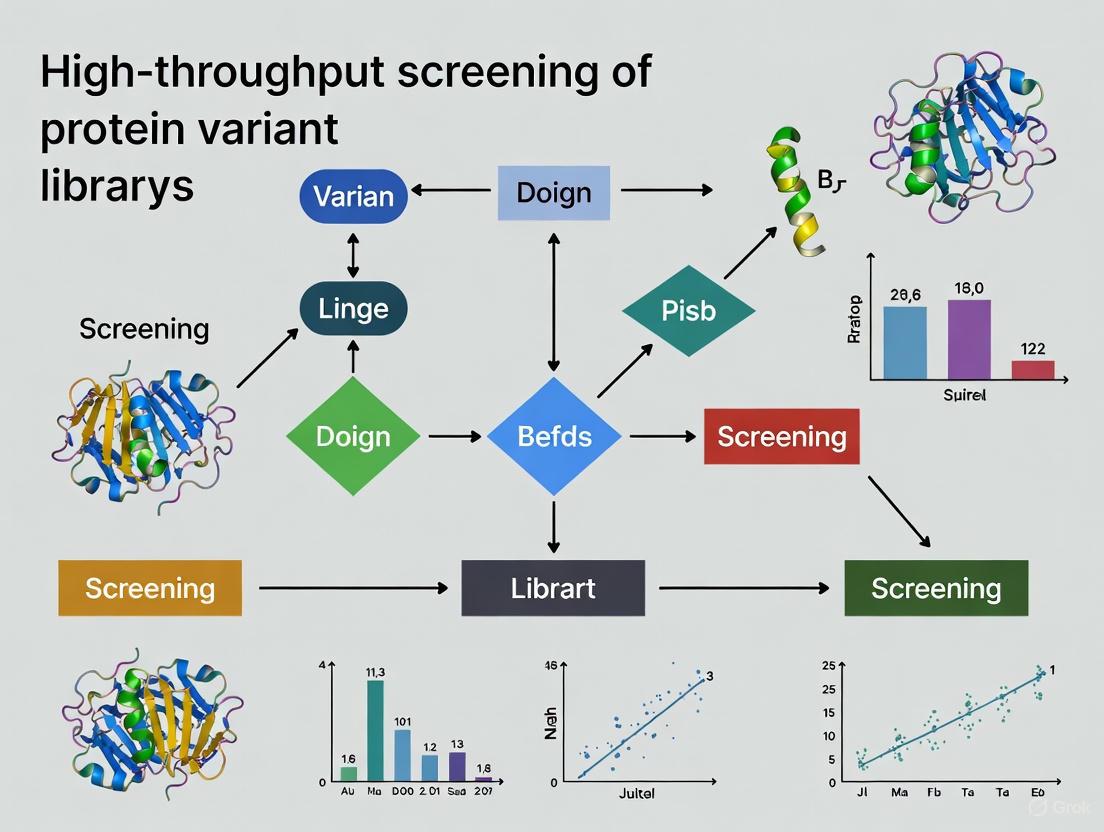

HTS Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the generalized HTS workflow for protein variant library screening, highlighting critical decision points and parallel processes:

Generalized HTS Workflow for Protein Variant Screening

Advanced Applications in Protein Variant Research

Specialized Screening Strategies for Protein Engineering

HTS approaches for protein variant libraries extend beyond simple activity measurements to more sophisticated functional assessments. Quantitative HTS (qHTS) is particularly valuable for protein engineering as it generates complete concentration-response profiles for each variant, providing rich data on mutational effects [1] [6]. This approach reveals not just whether a mutation affects function, but how it alters protein parameters including potency, efficacy, and cooperativity.

Differential Scanning Fluorimetry (DSF) represents another powerful application, monitoring changes in protein thermal stability (melting temperature, Tm) upon ligand binding or mutation [2]. In this method, the binding of a ligand to a protein variant typically increases its Tm, indicating stabilization [2]. This approach is readily adaptable to HTS formats and provides direct information on protein stability—a critical parameter in enzyme engineering and therapeutic protein development.

Screening for Pharmacological Chaperones

For disease-associated protein variants that misfold, HTS can identify pharmacological chaperones that stabilize proper folding and restore function [7]. The experimental design typically involves a fragment complementation system where correct folding and trafficking reconstitutes a reporter enzyme (e.g., β-galactosidase) [7]. This approach has successfully identified compounds that rescue trafficking-defective mutants in various protein misfolding disorders.

Future Perspectives

The future of HTS in protein variant research points toward even higher throughput and greater integration with computational methods. Artificial intelligence and machine learning are increasingly being applied to HTS data to identify patterns and predict compound activity, potentially reducing the experimental burden [4] [2]. Miniaturization continues to advance, with nanoliter and picoliter volumes becoming more common, reducing reagent costs and enabling larger screens [4] [5].

Three-dimensional screening approaches that incorporate more physiologically relevant models, such as organoids or spheroids, represent another frontier [2]. While currently lower in throughput, these systems may provide more predictive data for in vivo performance of protein variants, particularly for therapeutic applications. Finally, multiplexed screening formats that simultaneously measure multiple parameters from the same well are gaining traction, providing richer datasets from single experiments [2].

For researchers working with protein variant libraries, these advancements promise continued acceleration in our ability to navigate sequence-function landscapes and engineer proteins with novel properties. The integration of HTS with protein engineering represents a powerful synergy that will undoubtedly yield new insights and applications in the coming years.

Protein variant libraries are intentionally created collections of protein sequences with designed variations, serving as a fundamental resource in modern molecular biology and drug discovery. Within the context of high-throughput screening (HTS) research, these libraries enable the systematic exploration of sequence-function relationships, moving beyond individual protein characterization to comprehensive functional analysis at scale [8] [9]. The primary purposes of these libraries fall into two interconnected categories: directing the evolution of proteins with enhanced or novel properties, and performing deep functional analysis to understand the mechanistic role of individual amino acids.

The strategic value of this approach lies in its capacity to explore vast sequence landscapes without requiring complete a priori knowledge of protein structure-function relationships [10]. By generating and screening diverse variants, researchers can discover non-intuitive solutions that would be difficult to predict through rational design alone. This forward-engineering paradigm has revolutionized protein engineering, as recognized by the 2018 Nobel Prize in Chemistry awarded for directed evolution work [10].

The Directed Evolution Paradigm

Core Principles and Workflow

Directed evolution (DE) mimics natural selection in a controlled laboratory environment, compressing evolutionary timescales from millennia to weeks or months [10]. This process harnesses the principles of Darwinian evolution—genetic diversification followed by selection of the fittest variants—applied iteratively to steer proteins toward user-defined goals [11]. Unlike natural evolution, the selection pressure is decoupled from organismal fitness and is focused exclusively on optimizing specific protein properties defined by the experimenter [10].

A true directed evolution process is distinct from simple mutagenesis and screening; it requires iterative rounds of diversification and selection where beneficial mutations accumulate over successive generations [8]. This guided search through protein sequence space typically accesses more highly functional regions than can be readily accessed through single-round approaches [8]. The power of directed evolution stems from this iterative discovery process, where each round begins with the most "fit" mutants from the previous round, creating a cumulative improvement effect [8].

The following workflow diagram illustrates the iterative cycle that forms the core of directed evolution methodology:

Key Applications in Protein Engineering

Directed evolution has demonstrated remarkable success across multiple domains of protein engineering, particularly in three key areas where high-throughput screening of variant libraries provides a decisive advantage.

Enhancing Protein Stability: Directed evolution can significantly improve protein stability for biotechnological applications under challenging conditions such as high temperatures or harsh solvents [11]. This application is particularly valuable for industrial enzymes used in manufacturing processes where stability directly impacts efficiency and cost-effectiveness. The approach allows researchers to identify stabilizing mutations that often work cooperatively to rigidify flexible regions or strengthen domain interactions without requiring detailed structural knowledge [8].

Optimizing Binding Affinity: Protein variant libraries are extensively used to enhance binding interactions, particularly for therapeutic antibodies and other binding proteins [11]. Through iterative cycles of mutation and selection, researchers can achieve remarkable improvements in binding affinity. For instance, one study demonstrated a 10,000-fold increase in T-cell receptor binding affinity through directed evolution [8]. This application benefits from the ability of evolutionary approaches to identify peripheral residues that modulate binding affinity rather than simply identifying the central residues essential for binding [8].

Altering Substrate Specificity: A powerful application of variant libraries involves changing enzyme substrate specificity, enabling researchers to repurpose natural enzymes for industrial or therapeutic applications [11]. This is particularly valuable when natural enzymes have broad specificity or when a desired activity is only weakly present in naturally occurring proteins. Directed evolution can shift these specificity profiles dramatically, creating enzymes with novel catalytic properties that may not exist in nature [9].

Functional Analysis Through Variant Libraries

Elucidating Sequence-Function Relationships

Beyond direct engineering applications, protein variant libraries serve as powerful tools for fundamental studies of protein science. By analyzing the functional consequences of systematic sequence variations, researchers can determine how individual amino acids contribute to protein structure, stability, and function [8]. This approach addresses a central challenge in molecular biology: achieving a comprehensive understanding of how linear amino acid sequences encode specific three-dimensional structures and biological functions [8].

The functional analysis application is particularly valuable because it captures cooperative and context-dependent effects between residues that might be missed in single-mutation studies [8]. Different aspects of side-chain identity—including shape, charge, size, and polarity—contribute differently at various positions in the protein structure, and variant libraries enable researchers to systematically explore these contributions [8].

Complementing Traditional Approaches

Variant libraries and directed evolution provide complementary information to traditional techniques like alanine scanning. While alanine scanning identifies residues that are essential for function by mutating them to alanine and assessing the impact, directed evolution reveals which residues can modulate and improve function when mutated to various amino acids [8]. For example, in studies of antibody binding, alanine scanning typically identifies a central patch of residues critical for binding, while directed evolution identifies peripheral residues that can enhance affinity when appropriately mutated [8].

This complementary relationship extends to stability studies as well. Directed evolution approaches have demonstrated that stabilizing mutations are often broadly distributed across the protein surface rather than clustered near destabilizing modifications, revealing that proteins can have multiple regions that independently promote instability [8]. This insight would be difficult to obtain through targeted approaches alone.

Library Generation Methodologies

Diversification Strategies

The creation of a diverse library of gene variants is the foundational step that defines the boundaries of explorable sequence space in any directed evolution campaign [10]. The quality, size, and nature of this diversity directly constrain the potential outcomes, making the choice of diversification strategy a critical experimental decision [10].

Table 1: Protein Variant Library Generation Methods

| Method | Principle | Advantages | Limitations | Typical Library Size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Error-Prone PCR (epPCR) | Reduces DNA polymerase fidelity using Mn²⺠and unbalanced dNTPs [10] | Easy to perform; no prior knowledge needed; broad mutation distribution [9] [10] | Mutational bias (favors transitions); limited amino acid coverage (~5-6 alternatives per position) [10] | 10ⴠ- 10ⶠvariants [9] |

| DNA Shuffling | Fragmentation and recombination of homologous genes [10] [11] | Combines beneficial mutations; mimics natural recombination; can use nature's diversity [10] | Requires high sequence identity (>70%); crossovers biased to conserved regions [10] | 10ⶠ- 10⸠variants [9] |

| Site-Saturation Mutagenesis | Systematic randomization of targeted codons to all possible amino acids [10] [12] | Comprehensive coverage at specific positions; smaller, higher-quality libraries; ideal for hotspots [9] [10] | Limited to known target sites; requires structural or functional knowledge [10] | 10² - 10³ variants per position [12] |

| Oligonucleotide-Directed Mutagenesis | Uses spiked oligonucleotides during gene synthesis [12] | Controlled randomization; customizable mutation rate; targets specific regions [12] | Requires gene synthesis capabilities; limited to designed regions [12] | 10ⴠ- 10ⶠvariants [9] |

Strategic Implementation

The choice of diversification strategy represents a critical decision point in planning directed evolution experiments. The following decision pathway illustrates key considerations for selecting the most appropriate methodology:

Successful directed evolution campaigns often employ these methods sequentially rather than relying on a single approach [10]. An initial round of random mutagenesis (e.g., error-prone PCR) can identify beneficial mutations and potential hotspots, which can then be combined using recombination methods (e.g., DNA shuffling) in intermediate rounds [10]. Finally, saturation mutagenesis can exhaustively explore the most promising regions identified in earlier stages [10]. This combined strategy maximizes the exploration of productive sequence space while managing library size and screening constraints.

Screening and Selection Platforms

High-Throughput Methodologies

The identification of improved variants from protein libraries represents the critical bottleneck in directed evolution, with the success of any campaign directly dependent on the throughput and quality of the screening or selection method [10]. The power of the screening platform must match the size and complexity of the generated library, making methodology selection a pivotal experimental consideration [10].

Table 2: Screening and Selection Methods for Protein Variant Libraries

| Method | Principle | Throughput | Key Advantages | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Microtiter Plate Screening | Individual variant analysis in multi-well plates using colorimetric/fluorimetric assays [9] [10] | Medium (10²-10ⴠvariants) | Quantitative data; robust and established; automation-compatible [9] | Enzyme activity, stability, expression level [9] |

| Flow Cytometry (FACS) | Microdroplet encapsulation with fluorescent product detection [9] | High (10â·-10⸠variants/day) | Ultra-high throughput; sensitive; single-variant resolution [9] | Binding affinity, catalytic activity with fluorescent reporters [9] |

| Phage Display | Gene-protein linkage through phage surface expression [9] [11] | High (10â¹-10¹Ⱐvariants) | Direct genotype-phenotype linkage; enormous library sizes [9] | Antibody/peptide binding optimization [9] |

| In Vivo Selection | Coupling protein function to host survival [11] | Very High (limited by transformation efficiency) | Minimal hands-on time; automatic variant enrichment [11] | Metabolic pathway engineering, toxin resistance [11] |

Implementation Considerations

A crucial distinction in variant identification lies between screening and selection approaches. Screening involves the individual evaluation of each library member for the desired property, providing quantitative data on performance but typically with lower throughput [10]. In contrast, selection establishes conditions where the desired function directly couples to the survival or replication of the host organism, automatically eliminating non-functional variants and enabling much larger library sizes to be processed with less manual effort [10].

The development of high-throughput screening (HTS) systems has been transformative for directed evolution, enabling the rapid testing of thousands to hundreds of thousands of compounds or variants per day [13] [14]. Modern HTS platforms utilize automation, robotics, and miniaturization to conduct these analyses in microtiter plates with densities ranging from 96 to 1586 wells per plate, with typical working volumes of 2.5-10 μL [14]. The continuing trend toward miniaturization further enhances throughput while reducing reagent costs and material requirements [14].

The strategic principle "you get what you screen for" highlights the importance of assay design in directed evolution [10]. The screening method must accurately reflect the desired protein property, as evolution will optimize specifically for the assayed function. This consideration is particularly important when using proxy substrates or simplified assays that may not fully capture the desired activity in the final application environment [11].

Research Reagent Solutions Toolkit

Successful implementation of directed evolution and functional analysis requires specialized reagents and systems designed specifically for protein engineering workflows. The following toolkit outlines essential components for establishing a robust protein variant screening pipeline.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Protein Variant Library Studies

| Reagent/Solution | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Error-Prone PCR Kits | Introduces random mutations during gene amplification [10] | Optimize mutation rate (1-5 mutations/kb); consider polymerase bias in library design [10] |

| Site-Saturation Mutagenesis Kits | Creates all possible amino acid substitutions at targeted positions [12] | Use for hotspot optimization; NNK codons provide complete coverage [12] |

| Phage Display Vectors | Links genotype to phenotype via surface display [9] [11] | Ideal for binding selections; compatible with large library sizes (>10¹Ⱐvariants) [9] |

| Cell-Free Transcription/Translation Systems | Enables in vitro protein expression without cellular constraints [11] | Express toxic proteins; incorporate non-natural amino acids; use with emulsion formats [11] |

| HTS-Compatible Assay Reagents | Provides detectable signals (colorimetric/fluorogenic) in microtiter formats [9] [14] | Validate with wild-type protein first; ensure linear detection range; optimize for miniaturization [14] |

| Specialized Bacterial Strains | Host organisms for in vivo selection and library amplification [10] | Consider transformation efficiency; use mutator strains for continuous evolution [9] |

| Fmoc-Glu-OAll | Fmoc-Glu-OAll, CAS:144120-54-7, MF:C23H23NO6, MW:409.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Fmoc-4-Pal-OH | Fmoc-4-Pal-OH, CAS:169555-95-7, MF:C23H20N2O4, MW:388.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Protein variant libraries represent an indispensable toolset for both applied protein engineering and fundamental functional analysis. Through directed evolution, researchers can navigate the vast landscape of protein sequence space to solve practical challenges in biotechnology and therapeutic development. Simultaneously, these libraries enable deep mechanistic studies of sequence-function relationships that advance our basic understanding of protein biochemistry.

The continued refinement of library generation methods and screening technologies promises to expand the scope of addressable research questions, particularly as automation and miniaturization trends enable larger and more diverse libraries to be explored. The integration of computational approaches with experimental diversification creates particularly powerful hybrid methods that leverage growing structural and sequence databases.

For research and development leaders, strategic investment in protein variant library capabilities represents an opportunity to accelerate both discovery and optimization pipelines across pharmaceutical, chemical, and agricultural domains. The methodology's proven track record in generating intellectual property and commercial products underscores its practical value alongside its scientific importance.

Within high-throughput screening pipelines for protein engineering, the construction of diverse and high-quality variant libraries is a critical first step. Directed evolution experiments rely on such libraries to discover proteins with enhanced properties, such as improved stability, catalytic activity, or novel functions [15]. Among the various strategies available, random mutagenesis methods, particularly error-prone PCR (epPCR) and the use of mutator strains, provide powerful non-targeted approaches for generating genetic diversity. These methods are especially valuable when structural or functional information about the protein is limited, as they require no prior knowledge of key residues [15] [16]. This application note details the core principles, standardized protocols, and practical considerations for implementing these two foundational library construction techniques within a modern protein engineering context.

Core Principles and Methodologies

Error-Prone PCR (epPCR)

Error-prone PCR is a widely adopted technique that deliberately introduces random point mutations during the amplification of a target gene. This is achieved by manipulating PCR conditions to reduce the fidelity of the DNA polymerase, thereby increasing the error rate during DNA synthesis [15] [17].

The fundamental mechanism involves creating "sloppy" PCR conditions. Common strategies include:

- Divalent Cation Imbalance: Adding Mn²⺠to the reaction buffer in place of or in addition to the standard Mg²⺠cofactor [15] [18].

- Unbalanced dNTP Pools: Using unequal concentrations of the four deoxynucleotide triphosphates (dATP, dTTP, dGTP, dCTP) to promote misincorporation [15] [19].

- Error-Prone Polymerases: Utilizing DNA polymerases with inherently low proofreading activity, such as Taq polymerase, or specialized mutant polymerases designed for high error rates [15] [18].

Commercial kits, such as the Stratagene GeneMorph system or the Clontech Diversify PCR Random Mutagenesis Kit, simplify this process by providing pre-optimized reagent mixtures to achieve desired mutation frequencies [15] [17].

Mutator Strains

An alternative biological approach involves the use of mutator strains—E. coli strains deficient in multiple DNA repair pathways (e.g., mutS, mutD, mutT). When a plasmid containing the gene of interest is transformed and propagated in these strains, the host's impaired ability to correct replication errors results in the gradual accumulation of random mutations throughout the plasmid DNA [15] [17] [20].

A commonly used example is the XL1-Red strain (commercially available from Stratagene). The key advantage of this method is its technical simplicity, as it requires standard molecular biology techniques like transformation and plasmid purification, bypassing the need for specialized PCR protocols [15] [20]. A limitation is that the mutagenesis process is slower and can lead to an accumulation of deleterious mutations in the host genome over time, potentially affecting cell health [17].

Comparative Analysis of Random Mutagenesis Methods

Selecting the appropriate random mutagenesis method depends on the project's goals, available resources, and desired library characteristics. The following table summarizes the key parameters for direct comparison.

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of Error-Prone PCR and Mutator Strain Methods

| Parameter | Error-Prone PCR | Mutator Strain |

|---|---|---|

| Mutation Rate | High (up to 1 in 5 bases reported with analogues) [15] | Low to Moderate [18] |

| Mutation Type | Primarily point mutations (substitutions) [16] | Broad spectrum (substitutions, insertions, deletions) [17] |

| Typical Mutation Frequency | ~1–20 mutations/kb, controllable [15] [18] | Low and accumulates over time, less controllable [15] [18] |

| Library Size | Large (10â¶â€“10â¹), limited by cloning efficiency [15] [19] | Smaller, limited by number of transformation/propagation cycles [17] |

| Technical Complexity | Moderate (requires optimized PCR and cloning) | Low (relies on standard cloning and cell culture) |

| Primary Bias | Sequence and polymerase-dependent error bias; codon bias [15] | Generally mutagenesis is indiscriminate, affecting entire plasmid [15] |

| Time Investment | Rapid (can be completed in 1–2 days) | Slow (requires multiple passages over several days) [17] |

| Key Advantage | Controllable mutation frequency; rapid library generation | Technically simple; generates diverse mutation types |

| Key Limitation | Primarily generates point mutations; multiple biases [15] [16] | Low mutagenesis rate; can affect host health [15] [17] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Library Generation by Error-Prone PCR

This protocol is adapted from established methodologies [15] [19] and is suitable for introducing random mutations into a target gene for subsequent expression and screening.

Principle: The target gene is amplified under conditions that reduce the fidelity of DNA synthesis, leading to the incorporation of random nucleotide substitutions. The mutated PCR product is then cloned into an expression vector to create the variant library.

Reagents and Equipment:

- Template DNA (plasmid containing the gene of interest)

- High-fidelity or error-prone DNA polymerase (e.g., Taq, or kits from Stratagene/Clontech)

- Primers flanking the gene's cloning site

- 10x PCR Buffer (often supplied with Mg²âº)

- dNTP Mix (can be unbalanced, e.g., 1 mM dATP/dTTP, 0.2 mM dGTP/dCTP)

- MnClâ‚‚ solution (if not in the buffer)

- Thermo-cycler

- PCR purification kit

- Restriction enzymes and T4 DNA Ligase

- Expression vector

- Competent E. coli cells

Procedure:

- Reaction Setup: Prepare a 50 µL PCR reaction as follows:

- 10–50 ng template DNA

- 1x Polymerase Buffer

- 0.2–0.5 µM each primer

- Variable Mg²⺠or Mn²⺠(e.g., 0.5 mM MnCl₂)

- Unbalanced dNTPs (e.g., 0.2 mM dGTP, 0.2 mM dCTP, 1 mM dATP, 1 mM dTTP)

- 1–2 U DNA Polymerase

- Thermo-cycling:

- 95°C for 2 min (initial denaturation)

- 25–30 cycles of:

- 95°C for 30 sec (denaturation)

- 50–60°C for 30 sec (annealing)

- 72°C for 1 min/kb (extension)

- 72°C for 5–10 min (final extension)

- Product Purification: Clean the PCR product using a PCR purification kit to remove enzymes and salts.

- Cloning: Digest both the purified epPCR product and the destination expression vector with the appropriate restriction enzymes. Purify the digested fragments and ligate them using T4 DNA Ligase.

- Transformation and Library Expansion: Transform the ligation mixture into competent E. coli cells. Plate the cells on selective media to assess library size and complexity. Pool colonies and prepare a plasmid library for subsequent screening.

Troubleshooting:

- Low Mutation Rate: Increase the concentration of Mn²âº, use a more unbalanced dNTP ratio, or increase the number of PCR cycles.

- No/Low Yield: Optimize template quantity, primer annealing temperature, and ensure polymerase activity is suitable for the buffer conditions.

- Library Bias: Consider using a different error-prone polymerase or kit to alter the error bias profile [15] [18].

Protocol 2: Library Generation Using a Mutator Strain

This protocol describes the use of the commercially available E. coli XL1-Red strain for in vivo random mutagenesis [15] [17] [20].

Principle: The gene of interest, cloned in a plasmid, is transformed into a host strain with defective DNA repair mechanisms. As the cells divide, mutations accumulate randomly in the plasmid, which can then be harvested to create a variant library.

Reagents and Equipment:

- Plasmid DNA containing the gene of interest

- E. coli XL1-Red competent cells (e.g., from Stratagene)

- LB broth and agar plates with appropriate antibiotic (e.g., ampicillin)

- Plasmid DNA purification kit

Procedure:

- Initial Transformation: Transform the purified plasmid into competent XL1-Red cells according to the manufacturer's instructions.

- Selection: Plate the transformation mixture on LB agar containing the appropriate antibiotic. Incubate at 37°C for 24–48 hours.

- Library Propagation:

- Inoculate a single colony or a pool of colonies into 2–5 mL of LB medium with antibiotic. This is the first growth passage.

- Grow the culture for 24–48 hours at 37°C with shaking.

- Use a small aliquot (e.g., 1–10 µL) of this saturated culture to inoculate a fresh 2–5 mL LB medium with antibiotic. This is the second passage.

- Repeat for a third passage. Typically, 2–3 passages are required to accumulate a sufficient number of mutations [17].

- Plasmid Library Harvest: After the final passage, purify the plasmid DNA from the entire culture using a plasmid miniprep or midiprep kit. This pooled plasmid DNA constitutes your mutant library.

- Library Transformation for Screening: Transform the harvested plasmid library into a standard, high-efficiency E. coli expression strain for subsequent protein expression and screening. This step separates the mutated plasmids from the compromised mutator strain and amplifies the library.

Troubleshooting:

- Very Few Mutations: Ensure the host strain genotype is correct and increase the number of propagation passages.

- Poor Cell Growth: This is common in mutator strains due to accumulated genomic mutations. Use fresh cells directly from a commercial source or a recently prepared glycerol stock, and do not propagate the mutator strain for more than the recommended number of passages.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Reagents for Random Mutagenesis Library Construction

| Reagent / Resource | Function / Description | Example Products / Strains |

|---|---|---|

| Error-Prone PCR Kits | Pre-optimized reagent mixes for controlled random mutagenesis. | Stratagene GeneMorph Kit [15], Clontech Diversify PCR Kit [15] [17] |

| Low-Fidelity Polymerase | DNA polymerase with high inherent error rate for epPCR. | Taq DNA Polymerase [15] |

| Mutator Strain | E. coli strain with defective DNA repair for in vivo mutagenesis. | XL1-Red [15] [20] |

| Gateway Cloning System | High-efficiency recombination-based cloning to streamline library construction and reduce background [19]. | pDONR vectors, LR Clonase |

| High-Efficiency Competent Cells | Essential for achieving large library sizes after cloning. | Electrocompetent E. coli (e.g., 10â¹â€“10¹ⰠCFU/µg) |

| Chip-Synthesized Oligo Pools | For high-throughput, targeted library construction as a complementary or alternative approach [16]. | Custom oligo pools (e.g., GenTitan) |

| Fmoc-Gly-Gly-OH | Fmoc-Gly-Gly-OH, CAS:35665-38-4, MF:C19H18N2O5, MW:354.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Fmoc-D-Leu-OH | Fmoc-D-Leu-OH, CAS:114360-54-2, MF:C21H23NO4, MW:353.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Concluding Remarks

Both error-prone PCR and mutator strains offer robust and accessible pathways for constructing random mutagenesis libraries, a cornerstone of directed evolution campaigns. The choice between them hinges on project-specific needs: error-prone PCR is favored for its speed and controllable mutation frequency, making it ideal for rapidly generating large libraries of point mutants. In contrast, mutator strains offer technical simplicity and a broader spectrum of mutation types but are slower and offer less control.

For comprehensive coverage and to mitigate the inherent biases of any single method, researchers often employ a combination of these and other techniques, such as DNA shuffling or saturation mutagenesis, in successive rounds of evolution [15] [17]. Integrating these wet-lab methods with modern high-throughput screening technologies—such as fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) [21] and next-generation sequencing [16]—ensures that these foundational library construction methods remain vital for advancing protein engineering and drug development research.

Within high-throughput screening (HTS) for protein engineering, the construction of high-quality mutant libraries is a critical step in identifying variants with enhanced properties such as catalytic activity, stability, or specificity [22]. Targeted and focused libraries, built via oligonucleotide synthesis and site-directed mutagenesis, enable researchers to explore a defined region of protein sequence space that is most likely to contain beneficial mutations. Traditional library construction methods often employ a single degenerate codon at each mutation site, but this approach frequently introduces unwanted amino acids and stop codons, drastically reducing the library's functional diversity and screening efficiency [23]. This Application Note details a refined methodology for synthesizing cost-optimal targeted mutant protein libraries. By leveraging algorithmic design and multiple degenerate codons per site, this method maximizes the yield of beneficial variants, thereby accelerating the drug development pipeline for researchers and scientists.

Key Concept: Optimizing Library Design with Multiple Degenerate Codons

The conventional process of designing a mutant library involves selecting residue positions for mutation and specifying a set of beneficial amino acid substitutions for each position. A single degenerate codon (decodon) is typically used to encode the desired set at each site. However, the genetic code's degeneracy means that a single decodon often encodes for additional, unwanted amino acids.

- Traditional Single-Decodon Design: For example, when targeting the non-polar residues A, F, G, I, L, M, and V, the optimal single decodon (DBK) codes for 26 DNA variants. Only 18 of these code for the desired amino acids; the remaining 8 code for unwanted residues (C, R, S, T, W) [23].

- Novel Multi-Decodon Design: This problem is overcome by specifying the desired amino acid set (AA-set) using a combination of multiple decodons. Each decodon in this set codes for a subset of the desired amino acids without the unwanted additions. During synthesis, the annealing-based recombination of oligonucleotides containing these decodons produces a library exclusively composed of the targeted variants, effectively eliminating wasted screening effort on non-functional proteins [22] [23].

An algorithm was developed to calculate the minimum number of degenerate codons necessary to specify any given AA-set. This method, when integrated with a dynamic programming approach for oligonucleotide design, allows for the cost-optimal partitioning of a DNA sequence into overlapping oligonucleotides, ensuring the synthesis of a focused library with maximal beneficial variant yield [22].

Computational Design of Optimal Oligonucleotides

Algorithm for Minimal Decodon Set Selection

The core of the optimization is an algorithm that finds the smallest set of decodons that exactly covers a user-specified set of amino acids.

- Input: A set of desired amino acids (e.g., {A, F, G, I, L, M, V}).

- Process: The algorithm evaluates all possible decodons and identifies the minimal combination where the union of the amino acids they encode matches the target set perfectly, with no superfluous amino acids.

- Output: A minimal set of decodons. The use of this set ensures that every possible DNA variant synthesized will code only for a desired amino acid at that position, thereby eliminating all unwanted variants from the final library [23].

Dynamic Programming for Synthesis Cost Minimization

Once the minimal decodon sets for all mutation sites are determined, the next step is to design the oligonucleotides for assembly. A dynamic programming method is employed to partition the entire target DNA sequence with degeneracies into overlapping oligonucleotides.

- Objective: To minimize the total cost of DNA synthesis.

- Method: The algorithm evaluates all possible ways to fragment the sequence, considering the placement of mutation sites and the cost of synthesizing each resulting oligo. It finds the optimal partition that results in the lowest overall synthesis cost while maintaining full coverage of the desired sequence diversity [22] [23].

- Benefit: Computational experiments demonstrate that for a modest increase in DNA synthesis cost, the yield of beneficial protein variants in the produced mutant libraries can be increased by orders of magnitude. This effect is particularly pronounced in large combinatorial libraries, making screening efforts far more efficient [22].

The workflow below illustrates the optimized library construction process, from design to assembly.

Experimental Protocol: Library Construction Workflow

Oligonucleotide Synthesis and Quality Control

The success of a focused library hinges on the quality and accuracy of the synthesized oligonucleotide pools.

- Synthesis Technology: Oligo pools are synthesized in a massively parallel fashion on silicon chips using phosphoramidite chemistry. Advances in this technology now allow for the high-fidelity synthesis of oligos up to 300 nucleotides (nt) in length [24] [25].

- Minimizing Synthesis Errors: The primary side reaction limiting the synthesis of long oligonucleotides is depurination. This can be controlled by optimizing the detritylation process and fluid mechanics during synthesis, enabling the production of high-quality 150mer and longer oligo libraries [24].

- Quality Control (QC): Next-generation sequencing (NGS) is used to verify pool quality. Key performance metrics for a high-quality oligo pool include [25]:

- Uniformity: >90% of oligos represented within <2.0x of the mean.

- Error Rate: As low as 1:3000.

- Chimera Rate: In cloned pools, this should be minimized (e.g., as low as 1.5%) to prevent unwanted hybrid sequences.

Table 1: Key Reagents and Materials for Library Construction

| Item | Function/Description | Specifications/Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Custom Oligo Pool | Source of designed sequence diversity. | Length: Up to 300 nt [25].Scale: >0.2 fmol per oligo on average [25]. |

| DNA Polymerase | Amplification of oligo pools and assembly PCR. | High-fidelity polymerase recommended. |

| Restriction Enzymes | Cloning of assembled gene libraries into expression vectors. | Type depends on chosen vector. |

| Expression Vector | Framework for protein expression in host system. | Must be compatible with downstream screening. |

| Competent Cells | For transformation and library propagation. | High transformation efficiency is critical for library diversity. |

Step-by-Step Assembly and Cloning Protocol

The following protocol details the assembly of a focused mutant protein library from a synthesized oligo pool.

- Oligo Pool Reconstitution: Centrifuge the tube of dried oligo pool to collect contents at the bottom. Resuspend in nuclease-free TE buffer or water to create a stock concentration (e.g., 100 ng/µL).

- Gene Assembly PCR:

- Setup: In a PCR tube, combine the oligo pool with a high-fidelity PCR master mix. The overlapping regions of the oligos will serve as primers for assembly.

- Cycling Conditions:

- Initial Denaturation: 98°C for 2 minutes.

- Assembly (25-35 cycles):

- Denature: 98°C for 15 seconds.

- Anneal: 55-65°C (optimize based on oligo Tm) for 30 seconds.

- Extend: 72°C. Allow 15-30 seconds per kb of the final gene assembly.

- Final Extension: 72°C for 5-10 minutes.

- Amplification of Full-Library: Use the product from the assembly reaction as a template in a subsequent PCR with flanking primers that contain restriction sites compatible with your expression vector.

- Digestion and Purification: Digest both the amplified library insert and the expression vector with the appropriate restriction enzymes. Purify the digested products using a gel extraction or PCR cleanup kit.

- Ligation and Transformation:

- Ligate the library insert into the prepared vector at a molar ratio of approximately 3:1 (insert:vector).

- Transform the entire ligation reaction into high-efficiency competent cells. Plate a small aliquot to calculate library size, and use the rest to inoculate a liquid culture for plasmid DNA preparation.

- Library Validation: Isolate plasmid DNA from the liquid culture. Validate the library's diversity and sequence integrity by NGS before proceeding to protein expression and screening.

Application in High-Throughput Screening

The primary application of these targeted libraries is in quantitative high-throughput screening (qHTS) for protein engineering and drug discovery.

- Screening Context: In qHTS, thousands of protein variants are screened across a range of concentrations to generate concentration-response profiles. This approach has lower false-positive and false-negative rates compared to single-concentration HTS [6].

- Data Analysis: The resulting data are typically fitted to a Hill equation (also called the four-parameter logistic model) to estimate key parameters such as ACâ‚…â‚€ (potency) and E_max (efficacy) for each variant [6].

- Impact of Library Quality: A library constructed with the multi-decodon method provides a higher proportion of functional variants. This reduces the number of "flat" or null response profiles that can lead to false negatives, thereby increasing the hit rate and the reliability of the ACâ‚…â‚€ and E_max estimates used for lead candidate selection [6].

Table 2: Troubleshooting Common Issues in Library Construction and Screening

| Problem | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low library diversity | Low transformation efficiency, inefficient PCR assembly | Use higher efficiency competent cells; optimize PCR conditions and template amount. |

| High proportion of stop codons | Use of a single, non-optimal degenerate codon | Redesign the library using the multi-decodon algorithm to eliminate unwanted STOP codons [23]. |

| Poor sequence integrity in long oligos | Depurination side-reactions during synthesis | Ensure oligo synthesis provider uses optimized chemistry to control depurination [24]. |

| Unreliable ACâ‚…â‚€ estimates in qHTS | Concentration range does not define asymptotes, high noise | Ensure tested concentration range adequately covers the response curve; include experimental replicates [6]. |

Recombination techniques, such as DNA shuffling, represent a powerful methodology in the field of protein engineering, enabling the rapid evolution of proteins for therapeutic and industrial applications. These techniques mimic natural homologous recombination by fragmenting and reassembling related gene sequences, thereby accelerating the exploration of functional sequence space. This process facilitates the combination of beneficial mutations from different parent genes while efficiently removing deleterious ones, leading to the rapid generation of novel protein variants with enhanced properties.

Within the context of high-throughput screening for protein variant research, recombination methods are indispensable for constructing highly diverse and high-quality libraries. The rise of synthetic biology and precision design has made the construction of such mutagenesis libraries a critical component for achieving large-scale functional screening [16]. An optimal mutagenesis library possesses high mutation coverage, diverse mutation profiles, and uniform variant distribution, which are essential for deep functional phenotyping. These libraries serve as the foundational input for high-throughput screening platforms, which are projected to grow at a CAGR of 10.6%, underscoring their critical role in modern drug discovery and basic research [26].

Core Principles and Key Methodologies

Fundamental Principles of DNA Shuffling

DNA shuffling operates on the principle of in vitro homologous recombination. It begins with the fragmentation of a pool of related parent genes using enzymes or physical methods. These random fragments are then reassembled into full-length chimeric genes through a series of primerless PCR cycles, where fragments with regions of sequence homology prime each other. This is followed by a standard PCR amplification to generate the final library of recombinant genes. This process effectively crosses over homologous sequences, recombining beneficial mutations and creating new combinations that can exhibit additive or synergistic improvements in protein function, stability, or expression.

Comparison of Library Construction Techniques

The following table summarizes and compares DNA shuffling with other common library construction methods, highlighting their respective applications and limitations.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Mutagenesis Library Construction Methods

| Method | Principle | Key Applications | Advantages | Limitations/Drawbacks |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DNA Shuffling | Fragmentation & reassembly of homologous genes [16]. | Directed evolution, affinity maturation, pathway engineering [27]. | Recombines beneficial mutations from multiple parents; can remove deleterious mutations. | Requires significant sequence homology; library quality dependent on fragmentation efficiency. |

| Error-Prone PCR (epPCR) | Low-fidelity PCR to introduce random point mutations [16]. | Initial diversification when no structural data is available [16]. | Simple; requires no prior structural/functional information [16]. | Limited to point mutations (inefficient for indels); significant mutational preference/bias [16]. |

| Saturation Mutagenesis | Targeted replacement using degenerate oligonucleotides (e.g., NNK codons) [16]. | Scanning variant libraries, site-saturation libraries [27]. | Focuses diversity on specific residues; good for probing active sites. | Inherient amino acid bias and redundancy with conventional degenerate codons [16]. |

| Chip-Based Oligo Synthesis | PCR amplification from designed, chemically synthesized oligonucleotide pools [16]. | Deep mutational scanning, custom variant libraries, regulatory element screening [16]. | High precision and control; customizable; high synthesis efficiency and low error rate [27] [16]. | Higher initial cost; potential for oligonucleotide synthesis errors and chimeric sequence formation during PCR [16]. |

Application Notes for High-Throughput Screening

Integration with High-Throughput Screening Workflows

Recombination-generated libraries are a primary feedstock for High-Throughput Screening (HTS) platforms. The global HTS market, a cornerstone of modern drug discovery, is valued at an estimated USD 32.0 billion in 2025 and is projected to grow at a CAGR of 10.0% to reach USD 82.9 billion by 2035 [28]. These platforms leverage robotic automation, microplate readers, and sophisticated data analysis to screen thousands to millions of variants for a desired phenotype. The cell-based assays segment is the leading technology in this market, holding a 39.40% share, as it provides physiologically relevant data and predictive accuracy in early drug discovery [28].

The quality of the input library directly impacts HTS success. A key application is primary screening, which dominates the HTS application segment at 42.70% [28]. This phase involves the rapid testing of vast libraries to identify "hits" – variants with initial activity. Furthermore, the target identification segment is anticipated to grow at a significant CAGR of 12% from 2025 to 2035, highlighting the utility of HTS in discovering new biological targets for therapeutic intervention [28]. The quantitative data from HTS, such as IC50 values and dose-response curves, are used to prioritize lead candidates for further optimization [26].

Quantitative Analysis of Screening Outcomes

The efficiency of a screening campaign can be quantitatively evaluated using key metrics derived from the screening data.

Table 2: Key Quantitative Metrics for HTS and Library Analysis

| Metric | Description | Formula/Calculation | Application/Interpretation | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hit Rate | The proportion of active variants in a library. | (Number of Active Variants / Total Variants Screened) × 100 | Measures library quality and screening stringency; a very low rate may indicate a poor library. | ||

| Z'-Factor | A statistical parameter reflecting the quality and robustness of an HTS assay [26]. | ( 1 - \frac{3(\sigmap + \sigman)}{ | \mup - \mun | } )Where ( \sigma ) = standard deviation, ( \mu ) = mean,p = positive control, n = negative control. | An assay with Z' > 0.5 is considered excellent for HTS; ensures reliable hit identification [26]. |

| Mutation Coverage | The percentage of designed mutations successfully represented in the final library. | (Number of Positions with Successful Mutation / Total Number of Targeted Positions) × 100 | Assesses library construction fidelity. A study using chip-based synthesis achieved 93.75% coverage [16]. | ||

| Codon Redundancy | The number of codons that encode for the same amino acid. | Varies by degenerate codon (e.g., NNK has 32 codons for 20 amino acids). | Impacts screening burden; NNK excludes two stop codons, reducing redundancy vs. NNN [16]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Standard DNA Shuffling

This protocol outlines the core steps for creating a recombinant library via DNA shuffling.

Materials:

- Parental DNA Templates: A pool of related genes (≥70% sequence identity).

- DNase I: For random fragmentation of the DNA pool.

- DNA Purification Kit: For cleaning up DNA fragments.

- Taq DNA Polymerase (without Mg²âº): For the primerless reassembly PCR.

- dNTPs: Nucleotides for PCR.

- High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase: For the final amplification of full-length products.

- Gene-Specific Primers: For the final amplification step.

- Thermal Cycler.

Procedure:

- Prepare Parental DNA Pool: Mix 1-10 µg of each parental DNA sequence in equimolar ratios.

- Fragment DNA: Digest the DNA pool with DNase I (0.15 units/µg DNA) in a 100 µL reaction containing 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) and 10 mM MnCl₂ for 10-20 minutes at 25°C. The goal is to generate random fragments of 50-200 bp.

- Purify Fragments: Run the digested DNA on an agarose gel and excise and purify the 50-200 bp fragments.

- Reassemble Fragments (Primerless PCR): Set up a 50 µL reassembly PCR containing:

- Purified DNA fragments (10-100 ng)

- 0.2 mM dNTPs

- 2.5 U of Taq DNA Polymerase

- 1x corresponding PCR buffer (without MgClâ‚‚)

- 1-2 mM MgClâ‚‚ (concentration must be optimized).

- Cycling conditions: 95°C for 2 min; then 35-45 cycles of [95°C for 30 sec, 50-60°C (depending on homology) for 30 sec, 72°C for 30 sec]; then 72°C for 5 min.

- Amplify Full-Length Chimeras: Dilute the reassembly PCR product 10-50 fold. Use 1-5 µL of this dilution as a template in a standard 50 µL PCR with gene-specific primers and a high-fidelity DNA polymerase to amplify the full-length, reassembled genes.

- Clone and Screen: Clone the final PCR product into an appropriate expression vector and transform into host cells to create the library for high-throughput screening.

Protocol 2: High-Throughput Mutagenesis Library Construction via Chip-Based Oligo Synthesis

This modern protocol leverages high-throughput oligonucleotide synthesis for precise, scalable library construction, as demonstrated in a recent study [16].

Materials:

- Synthesized Oligonucleotide Pool: Commercially synthesized variant oligo pool (e.g., GenTitan Oligo Pool) [16].

- High-Fidelity, Low-Bias DNA Polymerase: e.g., KAPA HiFi HotStart, Platinum SuperFi II, or Hot-Start Pfu DNA Polymerase [16].

- PCR Reagents: dNTPs, buffer.

- Cloning Vector and Assembly Master Mix: e.g., for Gibson assembly.

- Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) Platform: For quality control.

Procedure:

- Library Design:

Amplification of Oligo Pool:

- Resuspend the delivered lyophilized oligo pool.

- Set up a 50 µL PCR reaction to amplify the diversified oligonucleotides. The study used KAPA HiFi HotStart ReadyMix and recommends high-fidelity, low-bias polymerases to minimize chimera formation [16].

Assembly into Vector:

- Assemble the amplified PCR products into the destination vector using a method like Gibson assembly.

- The use of an intermediate plasmid vector can enhance assembly efficiency [16].

Quality Control with NGS:

- Sequence the final constructed library using NGS.

- Analyze the data to determine key quality metrics like mutation coverage (achieved 93.75% in the model study) and mapping efficiency [16].

- Investigate unmapped reads to identify common errors such as oligonucleotide synthesis errors or chimeric sequences from incomplete PCR extension [16].

The Scientist's Toolkit

This section details the essential reagents and materials required for the construction of recombination-based libraries, as featured in the protocols above.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Library Construction

| Item | Function/Application | Key Characteristics & Recommendations |

|---|---|---|

| High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase | Amplifies DNA with minimal error introduction during PCR. | Essential for final gene amplification. KAPA HiFi HotStart and Platinum SuperFi II demonstrated higher amplification efficiency and lower chimera formation [16]. |

| DNase I | Enzymatically fragments parental DNA for the shuffling process. | Used in Protocol 1. Requires optimization of concentration and incubation time to achieve desired fragment size (50-200 bp). |

| Synthesized Oligo Pool | Serves as the source of designed mutations in modern library construction. | Commercially synthesized (e.g., GenTitan Oligo Pool). Offers high synthesis efficiency, low error rates, and is highly customizable [27] [16]. |

| DNA Assembly Master Mix | Seamlessly assembles PCR fragments into a vector (e.g., Gibson assembly). | Streamlines the cloning process, enabling high-throughput construction of variant libraries. |

| Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) | Provides high-quality control of the final variant library. | Allows assessment of mutation coverage, uniformity, and identification of construction errors (e.g., chimeras) [16]. |

| Fmoc-Phe(3,4-DiF)-OH | Fmoc-Phe(3,4-DiF)-OH, CAS:198560-43-9, MF:C24H19F2NO4, MW:423.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Boc-GABA-OH | Boc-GABA-OH, CAS:57294-38-9, MF:C9H17NO4, MW:203.24 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Workflow and Pathway Diagrams

Diagram 1: Library construction and screening workflow.

Diagram 2: HTS data analysis and lead selection.

In high-throughput screening (HTS) for drug discovery and functional genomics, the construction of optimal protein variant libraries is a critical determinant of success. These libraries serve as the foundational resource for identifying novel biologics, understanding protein function, and interrogating genetic variants. Three interdependent characteristics—diversity, size, and bias considerations—must be carefully balanced and optimized to ensure a library is both comprehensive and functionally representative. Within the broader context of a thesis on high-throughput screening of protein variant libraries, this application note details the core principles for library design and provides detailed protocols for their practical evaluation and application. We focus on contemporary methods that address historical limitations, particularly the challenge of bias in affinity selection platforms.

Core Characteristics of Optimal Libraries

The quality of a screening library is quantified through several key parameters. The following table summarizes these characteristics and their quantitative impact on library performance.

Table 1: Key Characteristics and Quantitative Metrics for Optimal Protein Variant Libraries

| Characteristic | Definition & Importance | Quantitative Metrics & Optimal Ranges |

|---|---|---|

| Diversity | The number of unique protein variants or sequences within a library. High diversity increases the probability of discovering rare, high-functionality variants. [29] | - Library Size: Ranges from ~30,000 to over 500,000 members in single experiments. [29]- Isobaric Compounds: Distinction of hundreds of isobaric compounds via tandem MS/MS fragmentation is crucial for accurate diversity assessment. [29] |

| Size | The total number of individual clones or variants in a library. A larger size increases coverage of theoretical sequence space. | - Affinity Selection: Platforms can screen libraries of 10^4 to 10^6 members in a single run. [29]- DELs: Historically limited by synthesis complexity and target incompatibility. [29] |

| Bias Considerations | Systematic errors or preferences introduced during library construction or screening that skew results. | - Synthesis Bias: Reaction conversion rates >55-65% are typically required for efficient combinatorial synthesis. [29]- Selection Bias: DNA barcodes in DELs can be >50 times larger than the small molecule, potentially interfering with target binding. [29] |

| Drug-Likeness | The fraction of library members possessing properties associated with successful therapeutic agents. | - Scored using Lipinski parameters (MW, logP, HBD, HBA, TPSA). [29]- Post-filtering, a majority of library compounds can satisfy drug-like property requirements. [29] |

Experimental Protocols for Library Construction and Evaluation

The following protocols provide detailed methodologies for critical steps in the generation and functional evaluation of high-quality variant libraries, from solid-phase synthesis to the assessment of non-coding variants.

Protocol: Solid-Phase Synthesis of Self-Encoded Libraries (SELs)

This protocol enables the barcode-free, combinatorial synthesis of diverse small-molecule libraries, circumventing the limitations of DNA-encoded libraries (DELs). [29]

1. Library Design and Building Block Selection

- Virtual Library Enumeration: Use a scoring script to enumerate a virtual library from a catalog of building blocks (e.g., 1000 Fmoc-amino acids, 1000 carboxylic acids).

- Building Block Scoring: Score each virtual library member based on Lipinski parameters (Molecular Weight, logP, Hydrogen Bond Donors, Hydrogen Bond Acceptors, Topological Polar Surface Area). [29]

- Selection: Purchase top-scoring building blocks based on the combined score (e.g., 62 amino acids, 130 carboxylic acids).

2. Solid-Phase Split and Pool Synthesis

- SEL 1 (Amino Acid-Based):

- SEL 2 (Benzimidazole Core):

- SEL 3 (Suzuki Cross-Coupling):

3. Quality Control

- Analyze the quality of the synthesis for each scaffold using liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) traces. [29]

- Evaluate the final library's drug-likeness by comparing the distribution of Lipinski parameters against the original virtual library. [29]

Protocol: Functional Evaluation of Genetic Variants using Saturation Genome Editing

This protocol uses CRISPR-Cas9 to systematically introduce and evaluate genetic variants in their native genomic context. [30]

1. Library Design and Delivery

- Design a CRISPR guide RNA (gRNA) library to target specific genomic loci for saturation editing.

- Clone the gRNA library into an appropriate inducible CRISPR-Cas9 vector system.

- Transduce the library into the target cell line.

2. Selection and Screening

- Induce CRISPR-Cas9 activity to generate a pool of variant cells.

- Apply a selective pressure relevant to the protein function being studied (e.g., drug selection, fluorescence-activated cell sorting).

- Harvest genomic DNA from the selected cell population.

3. Hit Identification and Decoding

- Amplify the integrated gRNA sequences from the genomic DNA by PCR.

- Analyze the gRNA representation using next-generation sequencing (NGS).

- Compare gRNA abundance before and after selection to identify variants that confer a functional advantage or disadvantage.

Protocol: Evaluating the Impact of Non-Coding Variants on TF-DNA Binding

This protocol details steps to quantify how non-coding variants affect transcription factor (TF) binding affinity using electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSAs). [31]

1. Protein Expression and Purification

- Expression: Express the recombinant DNA-binding domain of the TF (e.g., GATA4 with a hexahistidine tag) in IPTG-inducible BL21 DE3 E. coli. Induce with 1 mM IPTG at 18°C for 18-20 hours. [31]

- Purification:

- Resuspend the bacterial pellet in Column Buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 500 mM NaCl, 0.2% Tween-20, 30 mM Imidazole).

- Sonicate on ice and centrifuge at 15,000 × g for 30 min at 4°C.

- Incubate the supernatant with equilibrated Ni-NTA resin for 1 hour at 4°C.

- Wash sequentially with Column Buffer, Wash Buffer 1 (50 mM Imidazole), and Wash Buffer 2 (100 mM Imidazole).

- Elute the protein with Elution Buffer (500 mM Imidazole) in 1.8 mL fractions. [31]

- Buffer Exchange: Desalt the purified protein into Binding Buffer (10 mM HEPES pH 8.0, 100 mM NaCl, 0.5 μM Zinc acetate, 200 mM NH₄, 20% Glycerol) and concentrate to 10 μM. Store at -80°C. [31]

2. Preparation of Fluorescently Labeled DNA Probes

- Design and resuspend oligonucleotides containing the reference (non-risk) and alternate (risk) allele sequences at 100 μM. [31]

- Set up a primer extension reaction:

- 2.0 μL dsDNA (100 μM)

- 25 μL EconoTaq 2× Master Mix

- 3.0 μL IR700-labeled forward primer (100 μM)

- 20 μL Nuclease-free water [31]

- Run in a thermocycler: 95°C for 2 min (1 cycle); 68°C for 1 min; 72°C for 5 min; hold at 4°C. [31]

- Purify the labeled double-stranded DNA using a PCR purification kit. [31]

3. Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assay (EMSA)

- Binding Reaction: Incubate the purified TF (e.g., 1-10 nM) with the fluorescent DNA probe (e.g., 0.1-1 nM) in Binding Buffer. Include controls without protein and/or with unlabeled competitor DNA.

- Electrophoresis: Resolve the protein-DNA complexes from free DNA on a non-denaturing polyacrylamide gel under low ionic strength conditions at 4°C.

- Visualization and Quantification: Image the gel using an infrared fluorescence scanner. Quantify the band intensities for the bound and free DNA. Calculate the dissociation constant (Kd) or the fraction bound to determine the change in binding affinity between alleles. [31]

Visualization of Workflows and Pathways

The following diagrams, generated with Graphviz DOT language, illustrate key experimental workflows and logical relationships in library construction and evaluation.

Diagram 1: Barcode-free library construction and screening workflow.

Diagram 2: Key bias considerations and mitigation strategies in library design.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Successful execution of the protocols above relies on a set of essential reagents and materials. The following table details key solutions for researchers in this field.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Library Construction and Evaluation

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Fmoc-Amino Acids & Carboxylic Acids | Building blocks for solid-phase combinatorial synthesis of peptide and peptidomimetic libraries. [29] | Select based on virtual library scoring for drug-like properties (Lipinski parameters) to ensure final library quality. [29] |

| Ni-NTA Affinity Resin | Purification of recombinant hexahistidine-tagged DNA-binding proteins for EMSA and other binding assays. [31] | Allows efficient one-step purification under native or denaturing conditions. Resin can be regenerated and reused multiple times. [31] |

| IR700-labeled Primers | Generation of fluorescently labeled double-stranded DNA probes for EMSA, enabling sensitive near-infrared detection of protein-DNA complexes. [31] | Fluorescent labeling avoids the use of radioactive isotopes. The primer extension method ensures efficient label incorporation. [31] |