Generative AI for Protein Sequence Design: Models, Applications, and Future Frontiers

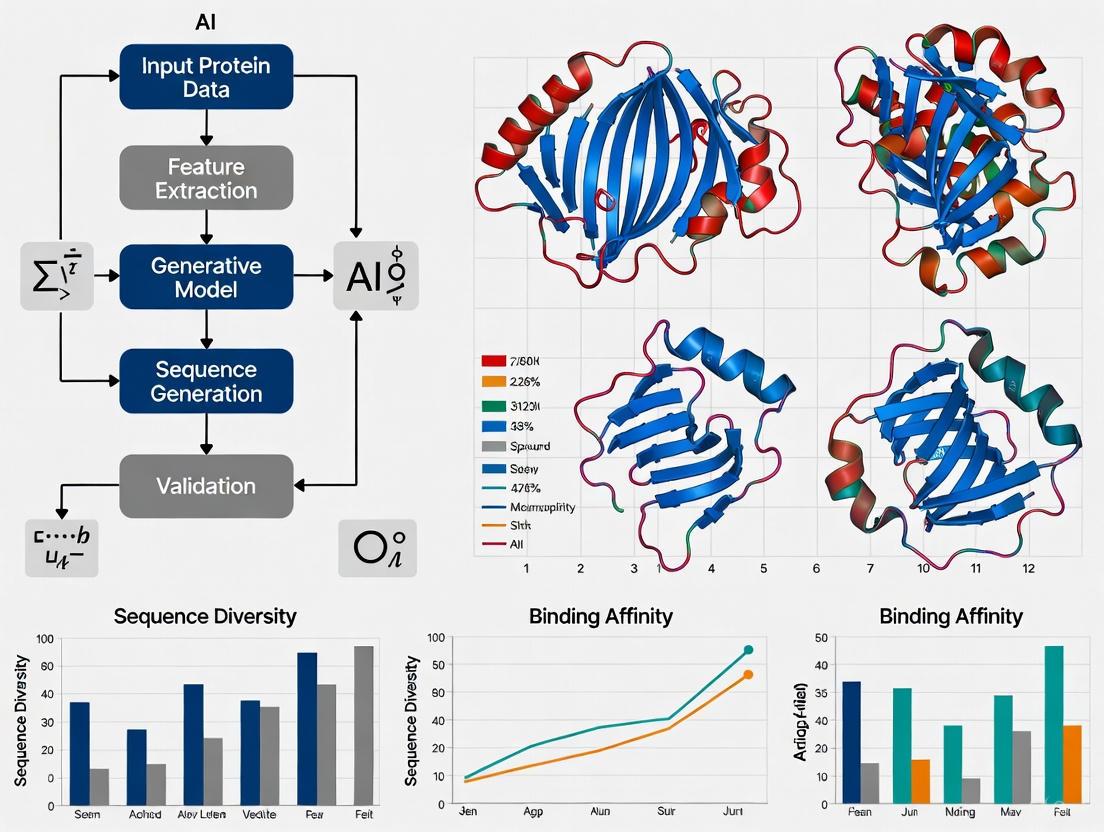

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the transformative impact of generative artificial intelligence on de novo protein sequence design.

Generative AI for Protein Sequence Design: Models, Applications, and Future Frontiers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the transformative impact of generative artificial intelligence on de novo protein sequence design. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational principles of protein language models and diffusion models, details pioneering architectures like ProGen and RoseTTAFold Diffusion, and examines their applications in creating novel therapeutics, enzymes, and biosensors. The content further addresses critical challenges such as data scarcity, model interpretability, and functional validation, while also discussing state-of-the-art benchmarking and experimental techniques. By synthesizing insights from cutting-edge research, this review serves as a strategic guide for navigating the rapidly evolving landscape of AI-driven protein engineering.

From Prediction to Creation: How Generative AI is Redefining Protein Design

De novo protein design represents a fundamental paradigm shift in biological engineering, moving beyond the modification of existing natural proteins to the ab initio creation of novel proteins with precisely desired structures and functions that do not exist in nature [1]. This approach fundamentally distinguishes itself from traditional protein engineering strategies, which typically involve altering naturally occurring proteins, or from protein structure prediction tools like AlphaFold, which primarily infer the three-dimensional (3D) structure from a known amino acid sequence [1]. The core impetus behind de novo design is to transcend the inherent limitations of natural proteins, which, as products of billions of years of evolution, are optimized for specific biological contexts and often exhibit suboptimal stability or functionality when repurposed for human applications [1] [2].

The field has evolved from early computational attempts in the 1980s to the current era of sophisticated generative artificial intelligence (AI) [1]. This transition marks a move from a "search and optimize" approach, characteristic of traditional methods like directed evolution, to a "generate and validate" methodology [1] [2]. Where conventional protein engineering is tethered to evolutionary history and requires experimental screening of vast variant libraries, de novo design offers a systematic route to functions that natural evolution has not explored, thereby fundamentally expanding the possibilities within protein engineering [2]. This is critical because the known natural protein fold space is approaching saturation, with novel folds rarely emerging through natural processes [2]. De novo design thus unlocks access to the vast, uncharted regions of the theoretical protein functional universe—the space encompassing all possible protein sequences, structures, and biological activities they can perform [2].

Key Principles and Methodological Frameworks

The Central Dogma of Protein Design and the Role of AI

The ultimate objective in protein design is to specify a desired function, design a structure that executes this function, and identify a sequence that folds into this structure [1]. Generative AI is increasingly inverting this "central dogma" of protein design through joint sequence-structure-function co-design frameworks that model the fitness landscape more effectively than models treating these modalities independently [1]. This holistic approach is crucial for generating complete proteins with functionally relevant, coherent sequences and full-atom structures [1].

At the heart of generative AI for protein design lie two principal families of models [1]:

- Protein Language Models (PLMs): These models, such as ProGen, treat protein sequences as linguistic texts and learn the underlying "grammar" of protein folding from vast datasets of natural sequences, enabling the generation of novel, functional sequences [1].

- Diffusion Models: Inspired by image generation, these models, such as RFdiffusion, progressively refine random noise into structured protein backbones by learning to reverse a noising process, allowing for the creation of novel protein structures [1] [3].

Overcoming the "Chicken-and-Egg" Problem

A fundamental technical hurdle in de novo design is the interdependent "chicken-and-egg problem" of combining the continuous nature of protein structure with the discrete nature of protein sequence [1]. Modern AI solutions address this through co-design approaches that manage the intrinsic interdependence between backbone, sequence, and sidechains throughout the generative process [1]. This capability is essential for transitioning from simple backbone scaffolding to genuine functional design where sequence and structure are mutually optimized for a desired outcome, such as creating specific binding sites or catalytic activities [1].

Integrative Optimization Frameworks

For complex design challenges with multiple competing objectives, multi-objective optimization frameworks provide a powerful approach. The Non-dominated Sorting Genetic Algorithm II (NSGA-II) represents one such framework, enabling the integration of different AI models like ProteinMPNN, AlphaFold2, and protein language models directly into the design process [4]. This allows for the explicit approximation of the Pareto front in the objective space, ensuring that final design candidates represent optimal trade-offs between competing specifications, such as stability in multiple conformational states [4].

Quantitative Analysis of Leading AI Models

The table below summarizes the capabilities, core methodologies, and key applications of major generative AI models driving progress in de novo protein design.

Table 1: Key Generative AI Models for De Novo Protein Design

| Model Name | Model Type | Key Capabilities | Core Methodology | Demonstrated Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ProGen [1] | Protein Language Model (PLM) | Generating functional protein sequences with predictable functions | 1.2B parameter model trained on 280M protein sequences; conditioned on taxonomic/keyword tags | Artificial proteins with catalytic efficiencies comparable to natural enzymes (e.g., 31.4% sequence similarity to natural lysozymes) [1] |

| RFdiffusion [1] [3] | Diffusion Model | Designing novel protein backbones, binders, symmetric oligomers | Fine-tuned RoseTTAFold on protein structure denoising; uses self-conditioning for improved performance | High-accuracy binders for influenza haemagglutinin; symmetric assemblies; metal-binding proteins [3] |

| Proteina [5] | Flow-based Generative Model | Unconditional backbone generation up to 800 residues | Scalable transformer architecture conditioned on hierarchical fold classes; trained on millions of synthetic structures | Production of diverse and designable proteins at unprecedented lengths [5] |

| AlphaDesign [1] [6] | Generative Framework | Accelerating creation of functional de novo proteins | Repurposes AlphaFold as a generative component within a design workflow | Moving protein design toward custom therapeutics and precision medicine [6] |

Experimental Validation and Application Protocols

Protocol: ValidatingDe NovoMonomeric Proteins with RFdiffusion

The following protocol outlines the key steps for generating and validating novel protein monomers using RFdiffusion, as demonstrated in foundational research [3].

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for De Novo Design

| Reagent/Tool | Function in Protocol | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| RFdiffusion Model [3] | Generative backbone design | Fine-tuned from RoseTTAFold; employs denoising diffusion probabilistic models (DDPMs) |

| ProteinMPNN [3] | Sequence design | Designs sequences for generated backbones; samples multiple sequences per design |

| AlphaFold2 [3] | In silico validation | Predicts structure from designed sequence; used with confidence metrics (pAE) for validation |

| E. coli Expression System [3] | Experimental production | Heterologous expression of designed protein sequences |

| Circular Dichroism (CD) Spectroscopy [3] | Experimental biophysical validation | Measures secondary structure and thermal stability |

Procedure:

- Unconditional Backbone Generation: Initialize RFdiffusion with random residue frames. Allow the model to perform iterative denoising steps (up to 200) to progressively generate a novel protein backbone from noise [3].

- Sequence Design: Input the generated backbone structure into ProteinMPNN. Sample multiple amino acid sequences (typically 8 per backbone) that are predicted to fold into the designed structure [3].

- In Silico Validation: Process each designed sequence-structure pair through AlphaFold2. A design is considered an in silico "success" if the AF2-predicted structure meets three criteria [3]:

- High confidence (mean predicted aligned error (pAE) < 5).

- Global backbone root mean-squared deviation (r.m.s.d.) < 2 Ã… from the designed structure.

- Local backbone r.m.s.d. < 1 Ã… on any scaffolded functional site.

- Experimental Characterization: Clone and express validated sequences in E. coli. Purify the expressed proteins and characterize them using Circular Dichroism (CD) spectroscopy to verify secondary structure and assess thermostability, comparing the results to the design model [3].

Protocol: Designing Protein Binders with Conditional RFdiffusion

This protocol details the application of RFdiffusion for designing proteins that bind to a specific target, a process known as binder design [3].

Procedure:

- Target Specification and Conditioning: Define the target protein structure. Provide this structural information to RFdiffusion as conditioning information during the generative process. The model is guided to create a binder backbone that complements the shape and chemical features of the target [3] [1].

- Binder Backbone Generation: Execute the conditional diffusion process. RFdiffusion generates a diversity of possible binder backbone structures that fit the target specification, unlike deterministic methods which produce limited diversity [3].

- Interface Sequence Design: Use ProteinMPNN to design sequences for the generated binder backbones, with special focus on optimizing the binding interface for complementary interactions with the target [3].

- Complex Validation: Use AlphaFold2 or RoseTTAFold to predict the structure of the designed binder in complex with the target. These networks serve as scoring functions to evaluate the likelihood of successful binding, increasing experimental success rates by approximately 10-fold [1] [3].

- Experimental Validation: Express the designed binders and the target protein. Use techniques such as cryogenic electron microscopy (cryo-EM) to resolve the structure of the complex and confirm it matches the design model with near-atomic accuracy [3].

The workflow for this binder design process is illustrated below.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Successful de novo protein design relies on a suite of specialized computational tools and experimental reagents. The following table details key components of the modern protein designer's toolkit.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Tool/Reagent | Category | Primary Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| RFdiffusion [1] [3] | Generative AI Model | Designs novel protein backbones and binders via diffusion | Generating symmetric oligomers and target-binding proteins from scratch |

| ProteinMPNN [3] [4] | Inverse Folding Model | Designs optimal amino acid sequences for a given protein backbone | Rapidly generating stable, foldable sequences for RFdiffusion-designed backbones |

| AlphaFold2 [3] [4] | Structure Prediction | Validates in silico that a designed sequence folds into the intended structure | Scoring design confidence (pAE, r.m.s.d.) before costly experimental testing |

| ProGen [1] | Protein Language Model | Generates novel, functional protein sequences conditioned on desired properties | Creating artificial enzymes with low sequence similarity but high functional similarity to natural counterparts |

| ESM-1v [4] | Protein Language Model | Predicts functional effects of sequence variations; used in mutation operators | Ranking residue positions for optimization in multi-objective design frameworks |

| NSGA-II Algorithm [4] | Optimization Framework | Integrates multiple AI models for problems with competing design goals | Designing fold-switching proteins that must be stable in multiple conformations |

| 2-carboxylauroyl-CoA | 2-carboxylauroyl-CoA, MF:C34H58N7O19P3S, MW:993.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Istradefylline-d3,13C | Istradefylline-d3,13C, MF:C20H24N4O4, MW:388.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Integrated Workflow for Multi-Objective Design

For complex design challenges, such as engineering proteins that must adopt multiple stable states or possess several optimal but competing traits, a multi-objective optimization approach is required. The following diagram illustrates an integrative workflow based on the NSGA-II algorithm, which combines multiple AI models to find optimal trade-off solutions [4].

This workflow demonstrates how different AI models are synergistically combined [4]:

- Informed Mutation: A mutation operator uses ESM-1v to identify the least native-like residue positions in a candidate protein and uses ProteinMPNN to redesign them, accelerating sequence space exploration [4].

- Multi-Model Scoring: Candidates are evaluated using objective functions derived from multiple models, such as the AF2Rank score (from AlphaFold2) for folding propensity and ProteinMPNN confidence [4].

- Pareto Optimization: The NSGA-II algorithm sorts candidates into successive Pareto fronts (F1, F2, F3, etc.), where designs in front F1 are non-dominated and represent the best trade-offs between all objectives. This explicit approximation of the Pareto front ensures the final design set contains optimal solutions for complex specifications [4].

De novo protein design, powered by generative AI, has fundamentally redefined the boundaries of protein engineering. By moving beyond natural sequences, it provides a systematic framework for accessing the vast, untapped potential of the protein functional universe. The integration of powerful generative models like RFdiffusion and ProGen with robust validation tools and sophisticated optimization frameworks enables the creation of bespoke proteins with tailor-made functions. As these methodologies continue to mature, they promise to accelerate the development of novel therapeutics, enzymes, and materials, firmly establishing de novo design as a mainstream approach in protein science and engineering.

The Limitations of Natural Proteins and Evolutionary Constraints

Natural proteins, products of millions of years of evolution, are fundamental to biological processes. However, their evolutionary history constrains their sequence and structural diversity, limiting their utility for human applications. The known natural fold space is approaching saturation, with recent innovations arising primarily from domain rearrangements rather than novel fold emergence [2]. Furthermore, natural proteins are optimized for biological fitness in specific niches, not for the stability, expressibility, or functional specificity required in industrial or therapeutic contexts [7] [2]. This application note details these inherent limitations and outlines how generative AI models provide a systematic framework to transcend these evolutionary constraints, enabling the creation of proteins with customized functions.

Quantitative Analysis of Natural Protein Constraints

The following table summarizes key quantitative limitations observed in natural proteins and the corresponding capabilities of AI-driven design.

Table 1: Constraints of Natural Proteins vs. AI-Driven Design Capabilities

| Constraint Feature | Observation in Natural Proteins | AI-Driven Design Solution | Quantitative Impact/Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fold Space Exploration | Natural fold space is nearing saturation; new functions primarily arise from domain recombination [2]. | De novo generation of novel folds and topologies not found in nature [2]. | AI has been used to create proteins with novel topologies (e.g., Top7) and large self-assembling complexes [7]. |

| Stability & Expression | Many natural proteins are marginally stable, leading to low functional yields in heterologous expression [7]. | Computational optimization of stability, enabling robust expression [7]. | Stability design enabled robust E. coli expression of malaria vaccine candidate RH5 with a ~15°C increase in thermal resistance [7]. |

| Sequence Sampling | Evolution samples sequence space via step-wise mutations, creating historical contingency and inaccessible states [8]. | Generative models sample sequence space combinatorially, bypassing evolutionary paths [2]. | A "zero-day" vulnerability test generated >76,000 functional variants of toxic proteins, demonstrating vast novel sequence generation [9]. |

| Structural Dynamics | Functional proteins are dynamic, but static structures dominate databases, limiting understanding [10]. | Emerging methods (e.g., AFsample2) predict conformational ensembles and alternative states [10]. | AFsample2 successfully predicted alternate conformations in 11 of 16 membrane transport proteins, with one TM-score improving from 0.58 to 0.98 [10]. |

| Functional Site Design | Limited by existing natural scaffolds and the rarity of specific catalytic geometries [7]. | De novo design of functional sites and binders on novel protein scaffolds [7] [2]. | De novo designed proteins have been engineered to generate new binders for proteins and small molecules, advancing "new-to-nature" activities [7]. |

Experimental Protocols for Evaluating Constraints and AI Designs

Protocol: Assessing Evolutionary and Population Constraint

This protocol quantifies residue-level constraints by integrating evolutionary and human population variation data, highlighting structurally and functionally critical regions [11].

Input Data Preparation:

Calculate Constraint Metrics:

- Evolutionary Conservation: For each position in the MSA, compute Shenkin's diversity score or a similar entropy-based measure [11].

- Population Constraint (MES): For each alignment column, compute the Missense Enrichment Score (MES).

MES = (Missense_count_position / Total_variants_position) / (Missense_count_domain / Total_variants_domain)- Determine the statistical significance (p-value) of the MES deviation from 1 using a two-tailed Fisher's exact test [11].

Classification and Structural Mapping:

- Classify residues as follows:

- Missense-depleted: MES < 1; p < 0.1 (high constraint)

- Missense-enriched: MES > 1; p < 0.1 (low constraint)

- Missense-neutral: p ≥ 0.1 [11]

- Map these classifications onto a high-resolution experimental or AI-predicted (e.g., AlphaFold) 3D structure.

- Analyze enrichment of missense-depleted sites in buried cores or binding interfaces using structural analysis software [11].

- Classify residues as follows:

Protocol: AI-Driven De Novo Protein Design and Validation

This protocol outlines a standard workflow for generating and validating novel proteins using generative AI, overcoming natural constraints [12] [2].

Define Design Objective: Specify the target, such as a novel fold, a small-molecule binding site, or a stabilized enzyme variant.

Generative Design Phase:

In Silico Validation:

- Structure Prediction: Use a structure predictor (e.g., AlphaFold 2/3) to validate that the designed sequence folds into the intended structure [10] [12].

- Virtual Screening: Employ tools like Boltz-2 to predict functional properties, such as binding affinity for a target, or other physics-based scoring functions to assess stability [10] [12].

Experimental Characterization:

- DNA Synthesis & Cloning: Translate the final protein sequence into an optimized DNA sequence for synthesis and cloning into an expression vector [12].

- Expression & Purification: Express the protein in a heterologous host (e.g., E. coli) and purify it.

- Biophysical Assays:

- Use Circular Dichroism (CD) or Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) to assess folding and thermal stability.

- Use Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) or Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC) to quantify binding affinity and specificity for functional designs.

- For enzymes, perform kinetic assays (e.g., spectrophotometric activity assays) to determine catalytic efficiency.

Protocol: Benchmarking AI-Generated Proteins Against Natural Variants

This protocol compares the properties of AI-designed proteins to natural and computationally evolved sequences to assess "naturalness" and performance [8].

Generate Sequence Sets:

- AI-Designed Sequences: Generate sequences for a target scaffold using a fixed-backbone design tool (e.g., RosettaDesign) [8].

- Evolved Sequences: Simulate evolution using an origin-fixation algorithm with the same energy function, introducing mutations sequentially and accepting them based on a fitness function derived from protein stability [8].

- Natural Sequences: Compile homologous sequences from natural databases.

Comparative Analysis:

- Calculate site-specific variability for each sequence set.

- Compare the variability patterns, particularly for surface residues. AI-designed sequences often exhibit excessive surface conservation compared to the more realistic variability profile of evolved and natural sequences [8].

- Experimentally express and purify top candidates from each set and measure yields, solubility, and thermal stability.

AI-Driven Protein Design Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Tools for AI-Driven Protein Design Research

| Tool / Reagent | Function / Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| AlphaFold 2/3 Server | Predicts 3D protein structures from sequences; AF3 extends to biomolecular complexes [10]. | Validating the fold of a designed protein or predicting its interaction with a DNA/ligand target [10]. |

| RFdiffusion | Generative AI model for creating novel protein backbones de novo or from partial specifications [12]. | Designing a novel protein scaffold with a predefined pocket for small-molecule binding [12]. |

| ProteinMPNN | Neural network for solving the "inverse folding" problem by designing sequences for a given backbone [12]. | Generating stable, foldable amino acid sequences for a backbone structure from RFdiffusion [12]. |

| Boltz-2 | Open-source model predicting protein-ligand complex structure and binding affinity simultaneously [10]. | Rapid virtual screening of designed binders, reducing synthesis needs [10]. |

| Rosetta Software Suite | Physics-based modeling suite for protein design, structure prediction, and refinement [2]. | Precisely designing an enzyme active site or performing energy-based stability calculations [2]. |

| gnomAD Database | Public catalog of human genetic variation, including missense variants [11]. | Calculating population constraint (MES) to identify functionally critical residues [11]. |

| 2'-Deoxyuridine-d | 2'-Deoxyuridine-d, MF:C9H12N2O5, MW:229.21 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Benzylmethylether-d2 | Benzylmethylether-d2, MF:C8H10O, MW:124.18 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Natural proteins are inherently limited by the slow, path-dependent process of evolution, which favors biological fitness over biotechnological utility. These constraints manifest as marginal stability, limited exploration of sequence-structure space, and an over-reliance on existing folds. Generative AI models fundamentally disrupt this paradigm. By providing a systematic engineering framework for de novo protein design, they enable researchers to create stable, functional proteins that transcend nature's limitations, accelerating discovery in therapeutics, synthetic biology, and green chemistry.

Core AI Architectures: Protein Language Models (PLMs) vs. Diffusion Models

The design of novel protein sequences represents a frontier in biotechnology, with profound implications for therapeutic development, enzyme engineering, and synthetic biology. Generative artificial intelligence (AI) is at the forefront of this revolution, enabling researchers to move beyond natural evolutionary templates. Two core AI architectures have emerged as particularly powerful: Protein Language Models (PLMs) and Diffusion Models. While both can generate protein sequences, they are founded on distinct principles and excel in different applications. PLMs, inspired by natural language processing, treat amino acid sequences as texts to learn evolutionary patterns and semantic meaning. In contrast, Diffusion Models are generative frameworks that learn to construct data by iteratively denoising random noise, making them exceptionally suited for tasks requiring precise geometric control, such as structure-based design. This Application Note provides a comparative analysis of these architectures, summarizes key quantitative data in structured tables, and outlines detailed experimental protocols for their application in protein sequence design.

2.1 Protein Language Models (PLMs) PLMs are trained on millions of natural protein sequences from databases like UniProt, learning the statistical patterns and "grammar" of protein sequences in a self-supervised manner. Models like ESM-2 [13] and ProGen2 [14] develop rich, contextual representations for each amino acid in a sequence. Their strength lies in understanding sequence-based semantics, which makes them excellent for:

- Function Prediction: Extracting features for predicting protein function [15].

- Sequence Generation: Generating novel, plausible protein sequences de novo [14].

- Protein-Protein Interaction (PPI) Prediction: Specialized models like PLM-interact jointly encode protein pairs to predict physical interactions [13].

A key limitation of standard PLMs is their focus on sequence, often without explicit 3D structural reasoning, which can restrict their utility for designing proteins where precise spatial arrangement is critical.

2.2 Diffusion Models Diffusion Models for protein design, such as RFdiffusion and CPDiffusion, learn to generate data through a process of iterative denoising [16] [17]. Starting from pure random noise, the model applies a learned reverse process over multiple steps to produce a coherent output. This architecture is inherently well-suited for:

- Inverse Folding: Generating sequences that fold into a specific backbone structure [17] [18].

- Structure Generation: Directly creating novel and diverse 3D protein structures, as demonstrated by RFdiffusion for nanobodies and protein backbones [16].

- Conditional Generation: Precisely steering the generation of sequences or structures based on conditions like secondary structure, target binding sites, or desired properties [17] [19] [18].

The primary challenges for diffusion models are their significant computational cost and the expertise required for fine-tuning and guiding the generation process [16].

Table 1: Core Architectural Comparison: PLMs vs. Diffusion Models

| Feature | Protein Language Models (PLMs) | Diffusion Models |

|---|---|---|

| Core Principle | Learned from evolutionary-scale sequence data using transformer architectures; treats sequences as language. | Learns a data distribution by iteratively denoising from random noise. |

| Primary Input | Amino acid sequences (text-like). | Can be sequences, structural coordinates (atom, backbone), or 3D voxels. |

| Primary Output | Novel sequences, sequence embeddings for prediction tasks. | Novel sequences conditioned on structure, or novel 3D structures directly. |

| Key Strength | High-level understanding of evolutionary patterns and sequence semantics; efficient feature extraction. | Fine-grained control over 3D geometry and structural diversity; excels at spatial reasoning. |

| Common Tasks | Function prediction, sequence generation, PPI prediction, fitness prediction. | Inverse folding, de novo structure design, motif scaffolding, property-guided design. |

| Representative Models | ESM-2, ProGen2, PLM-interact [13] [14] | RFdiffusion, CPDiffusion, DPLM [16] [17] [18] |

Quantitative Performance Benchmarking

Empirical studies highlight the complementary strengths of both architectures. The following table consolidates key performance metrics from recent research.

Table 2: Key Experimental Results from Recent Studies

| Study & Model | Model Type | Task | Key Performance Metric & Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| CPDiffusion [17] | Conditional Diffusion | Design of programmable endonucleases (pAgo proteins). | Success Rate: 24/27 (89%) and 15/15 (100%) of generated proteins for two templates showed unambiguous ssDNA cleavage activity. Enhanced Function: ~74% (20/27) of active designs showed superior activity to wild-type. |

| PLM-interact [13] | Protein Language Model | Cross-species Protein-Protein Interaction (PPI) prediction. | AUPR: Achieved state-of-the-art AUPR on mouse (0.86), fly (0.78), worm (0.80), yeast (0.71), and E. coli (0.72) when trained on human data. |

| Generative AI for PiggyBac [14] | Protein Language Model (ProGen2) | Design of synthetic transposases for gene editing. | Activity: 7 of 22 tested synthetic variants showed higher excision activity than the natural hyperactive benchmark (HyPB). One variant, "Mega-PiggyBac," significantly improved integration efficiency. |

| RFdiffusion for Nanobodies [16] | Diffusion | De novo generation of nanobody backbone structures. | Structural Accuracy: Generated nanobody structures achieved Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD) values below 2.0 Ã… compared to reference structures, indicating high structural similarity. |

Experimental Protocols

4.1 Protocol A: Conditional Sequence Generation using a Diffusion Model (e.g., CPDiffusion)

This protocol outlines the process for generating novel, functional protein sequences conditioned on a specific backbone structure, as demonstrated for Argonaute proteins [17].

1. Model Training and Conditioning:

- Objective: Train a conditional denoising diffusion probabilistic model (DDPM) to learn the mapping from protein backbone structures to sequences that fold into that structure.

- Training Data: A base model is first pre-trained on a large set of diverse protein structures (e.g., ~20,000 structures from CATH 4.2) to learn general protein folding principles [17].

- Conditioning: The model is conditioned on specific constraints during the reverse diffusion process. For CPDiffusion, this includes:

- Backbone Structure: The 3D coordinates of the target backbone (e.g., from a wild-type KmAgo or PfAgo structure).

- Secondary Structure: The predicted or assigned secondary structure elements (helices, sheets, coils) for the backbone.

- Conserved Residues: Masking specific positions (e.g., catalytic tetrads) to remain fixed or highly conserved throughout the generation process [17].

- Loss Function: The model is trained to minimize the variational lower bound on the negative log-likelihood, often implemented as a mean squared error or categorical cross-entropy loss between the predicted and true amino acid distributions [17] [19].

2. Sequence Generation and In Silico Screening:

- Generation: Run the trained CPDiffusion model to generate 100s of novel sequences. The process starts from random noise and iteratively denoises it, guided by the target backbone and other conditions over multiple steps (e.g., 1000 steps).

- Sequence Identity Filtering: Filter generated sequences to ensure diversity by removing those with >70% sequence identity to the wild-type template [17].

- Structure Prediction and Validation: Use a high-accuracy structure prediction tool like AlphaFold2 or ESMFold to predict the 3D structure of the generated sequences.

- Quality Control: Screen predicted structures for:

- Structural Integrity: Packing quality, presence of knots, and overall fold stability.

- Condition Adherence: Verify that the predicted structure matches the conditioning backbone (e.g., using TM-score or RMSD) and that functional motifs are preserved.

3. Experimental Validation:

- Gene Synthesis and Cloning: Codon-optimize and synthesize the DNA sequences for the top-ranking generated proteins. Clone them into an appropriate expression vector.

- Protein Expression and Purification: Express the proteins in a suitable host system (e.g., E. coli). Purify the proteins using affinity chromatography and validate solubility and stability (e.g., via SDS-PAGE and size-exclusion chromatography).

- Functional Assay: Perform a functional assay specific to the protein family. For pAgo proteins [17], this was a single-strand DNA (ssDNA) cleavage assay, measuring cleavage activity and comparing it to the wild-type protein.

- Biophysical Characterization: Determine thermostability by measuring the melting temperature (Tm) using differential scanning fluorimetry (DSF).

4.2 Protocol B: De Novo Protein Design using a Protein Language Model (e.g., ProGen2)

This protocol describes the use of a pLLM for the de novo generation of novel protein sequences, such as synthetic transposases [14].

1. Data Curation and Model Fine-Tuning:

- Bioprospecting: Compile a large, diverse set of natural protein sequences for the target family. For PiggyBac transposases, this involved computationally screening >31,000 eukaryotic genomes to identify ~13,000 novel sequences [14].

- Fine-Tuning: Take a pre-trained pLLM (e.g., ProGen2) and fine-tune it on the curated, family-specific dataset. This process teaches the model the specific biochemical and structural "language" of the protein family of interest.

2. Sequence Generation and Selection:

- Unconditional Generation: Use the fine-tuned model to generate thousands of novel protein sequences. The model functions as a language model, predicting the next likely amino acid in a sequence.

- Sequence Analysis: Analyze the generated sequences for:

- Novelty: Compare against natural sequences in databases (e.g., using BLAST) to ensure they are distinct.

- Plausibility: Check for the presence of known functional domains and motifs critical for activity (e.g., DNA-binding domains like zinc fingers in transposases).

- AlphaFold3 Analysis: Use AlphaFold3 to predict the structures of selected variants and identify key structural features and fusion architectures [14].

3. Experimental Characterization:

- DNA Synthesis and Cloning: Synthesize genes for a subset (e.g., 20-30) of the most promising generated sequences and clone them into expression vectors.

- Functional Testing in Cell-Based Assays: Transfert the constructs into mammalian cells and perform activity assays. For transposases [14], this involves:

- Excision Assay: Measure the ability of the synthetic transposase to remove a transposon from a donor plasmid.

- Integration Assay: Quantify the efficiency of transgene integration into the host genome.

- Comparison to Wild-Type: Compare the activity of the synthetic proteins directly to the current gold-standard natural protein (e.g., hyperactive PiggyBac, HyPB).

Table 3: Key Resources for AI-Driven Protein Design

| Resource / Reagent | Type | Function in Workflow | Example Sources / Tools |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-trained Models | Software | Foundational models for fine-tuning or feature extraction. | ESM-2, ProGen2 [13] [14], RFdiffusion [16] |

| Structure Prediction Tools | Software | Validates structural integrity of generated sequences in silico. | AlphaFold2/3, ESMFold, RosettaFold [20] [2] [14] |

| Protein Structure Databases | Database | Source of training data and templates for conditioning. | Protein Data Bank (PDB), CATH, AlphaFold DB [17] [2] |

| Protein Sequence Databases | Database | Source for training PLMs and for sequence similarity checks. | UniProt, MGnify [2] [15] |

| Gene Synthesis Service | Commercial Service | Converts in silico designed sequences into physical DNA for testing. | Various commercial providers |

| Activity-Specific Assay Kits | Wet-lab Reagent | Measures the biochemical function of the designed protein. | e.g., ssDNA cleavage assay kits [17], transposition assay systems [14] |

Protein Language Models and Diffusion Models are powerful, complementary architectures driving the field of generative protein design. PLMs provide an unparalleled understanding of sequence-based evolutionary principles, making them ideal for function-oriented design and prediction. Diffusion Models offer superior control over 3D structural geometry, enabling the design of proteins with precise shapes and novel topologies. The choice between them is not a question of which is superior, but which is the right tool for the specific research objective. As evidenced by the protocols and data herein, a hybrid approach that leverages the strengths of both architectures may ultimately provide the most robust path forward for creating the next generation of synthetic biological tools and therapeutics.

The Shift from Structure Prediction to Generative Design with AlphaFold and Beyond

The field of structural biology has undergone a profound transformation, moving from the challenge of predicting protein structures to the frontier of generating novel protein sequences and complexes. This shift represents a fundamental change in the application of artificial intelligence (AI) in biology. Initially, breakthroughs like AlphaFold provided unprecedented accuracy in determining how amino acid sequences fold into three-dimensional structures [21]. Today, the field is leveraging these predictive frameworks as foundations for generative models that design proteins with custom structures and functions [10] [22] [23]. This document details the experimental protocols and applications driving this transition, providing researchers with practical methodologies for generative protein design within the broader context of AI-driven biological discovery.

Fundamental Technologies and Research Reagents

The following toolkit comprises essential computational resources and AI models that form the foundation of modern generative protein design workflows.

Table 1: Essential Research Reagents for Generative Protein Design

| Tool Name | Type | Primary Function | Application in Generative Design |

|---|---|---|---|

| AlphaFold 3 [10] [24] | Structure Prediction Network | Predicts 3D structures of proteins, DNA, RNA, ligands, and their complexes. | Serves as an "oracle" for in silico validation of designed protein complexes and for network inversion. |

| AlphaFold 2 [21] [23] | Structure Prediction Network | Highly accurate single-protein structure prediction. | Core engine for inversion-based design (AF2-Design) and structural validation. |

| ProteinMPNN [10] | Sequence Design Neural Network | Inverse-folding tool that generates sequences for a given protein backbone. | Rapid sequence design following backbone generation with tools like RFdiffusion. |

| RFdiffusion [10] | Generative Backbone Design | Designs novel protein backbone structures based on user constraints. | De novo backbone generation for custom folds and binding interfaces. |

| ProtGPT2 [22] | Generative Language Model | Decoder-only transformer that generates novel protein sequences unsupervised. | Exploration of novel, stable protein sequences in unexplored regions of sequence space. |

| ESM2 [22] | Protein Language Model | Large-scale encoder model that learns representations from protein sequences. | Used for fitness prediction and guiding sequence sampling for defined backbones. |

| Boltz-2 [10] | Structure & Affinity Model | Jointly predicts protein-ligand 3D structure and binding affinity. | Accelerates drug discovery by combining structure prediction with functional affinity assessment. |

| ProtGPS [25] | Localization Prediction & Design | Predicts and generates protein subcellular localization sequences. | Design of proteins targeting specific cellular compartments, improving therapeutic efficacy. |

Core Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: De Novo Protein Design via AlphaFold Network Inversion

This protocol details the inversion of the AlphaFold 2 network to generate novel protein sequences that fold into a user-defined target structure, a method known as AF2-Design [23].

Workflow Overview:

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Input Preparation: Define the target protein backbone's 3D atomic coordinates in PDB format. This scaffold serves as the fixed objective for sequence generation.

- Sequence Initialization: Initialize a starting amino acid sequence of corresponding length. This can be a random sequence or a sequence from a natural protein with a similar fold.

- Structure Prediction: Process the current sequence through AlphaFold 2 in single-sequence mode (disabling multiple sequence alignments and templates) to obtain a predicted structure [23].

- Loss Calculation: Compute the Frame Aligned Point Error (FAPE) loss between the predicted structure and the target backbone. The FAPE loss measures the local distance differences between aligned residue frames, making it rotation- and translation-independent [23].

- Sequence Optimization: Backpropagate the FAPE loss through the AlphaFold network to calculate the gradient with respect to the input sequence. Use this gradient to update the amino acid sequence via gradient descent, minimizing the structural deviation.

- Iteration: Repeat steps 3-5 until the loss converges or reaches a satisfactory threshold. Using all five AlphaFold ensemble models during backpropagation reduces overfitting.

- Post-Design Optimization: Early implementations often resulted in surfaces overpopulated with hydrophobic residues. A final optimization step, such as replacing surface hydrophobic residues with hydrophilic ones, is frequently required to ensure solubility [23].

- Validation: The final designed sequence must be validated in silico by a full AlphaFold prediction and, for experimental work, in vitro for stability and correct folding.

Protocol 2: Generative Protein Sequence Design with Language Models

This protocol uses protein language models, like ProtGPT2, to generate novel, stable protein sequences unconditionally or conditioned on specific families [22].

Workflow Overview:

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Model Selection: Choose a pre-trained generative language model. For unconditional generation (exploring entirely novel sequence space), use models like ProtGPT2 or RITA. For generation focused on a specific protein family, select a model capable of being fine-tuned [22].

- Conditioning (Optional): For targeted design, fine-tune the base model on a multiple sequence alignment (MSA) of the protein family of interest. This conditions the model's probability distribution to generate sequences belonging to that family.

- Sequence Generation: Employ an autoregressive generation process. The model predicts the next amino acid in the sequence based on all previous ones, building the protein from N- to C-terminus.

- In Silico Validation: Process generated sequences through structure prediction tools (e.g., AlphaFold) to confirm they adopt a stable, folded structure. Analyze predicted pLDDT scores and structural metrics.

- Property Filtering: Screen sequences for desired biophysical properties using predictive models. Key properties include:

- Predicted Stability: Using tools like ESM2 or dedicated stability predictors.

- Solubility: Predicting aggregation-prone regions.

- Function: For example, using ProtGPS to ensure correct subcellular localization if required [25].

- Experimental Characterization: The top-ranking sequences should be synthesized and experimentally tested for expression, stability, and function.

Protocol 3: Functional Protein Complex Design with Integrated Tools

This protocol describes an integrated workflow for designing functional proteins, such as binders or enzymes, by combining structure generation (RFdiffusion), sequence design (ProteinMPNN), and validation (AlphaFold 3) [10].

Workflow Overview:

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Problem Definition: Specify the functional objective (e.g., "design a protein that binds to target protein X at site Y").

- Backbone Generation: Use RFdiffusion to generate a novel protein backbone structure. The generation process can be conditioned on the 3D structure of the target site to create complementary shapes.

- Sequence Design: Pass the generated backbone to ProteinMPNN, which solves the "inverse folding" problem by designing a sequence that is most likely to fold into that specific structure. This step optimizes for folding stability.

- Complex Validation: Use AlphaFold 3 to model the 3D structure of the complex between the designed protein and its target. This assesses the quality of the binding interface [10] [26].

- Functional Scoring: Employ specialized models to evaluate function. For drug targets, use Boltz-2 to predict the binding affinity between the designed protein and its target, going beyond structure to function [10].

- Iterative Refinement: If the design fails to meet criteria (e.g., poor predicted affinity, incorrect binding mode), iterate the process by adjusting RFdiffusion parameters or sequence design constraints.

- Experimental Testing: Express the designed protein and characterize its function experimentally using techniques like surface plasmon resonance (SPR) for binding affinity or cellular assays for functional activity.

Performance Metrics and Validation

Rigorous in silico validation is critical before moving to costly experimental stages. The following metrics are standard for evaluating generative design outputs.

Table 2: Key Performance Metrics for Generative Protein Designs

| Metric | Description | Interpretation & Target Value |

|---|---|---|

| pLDDT [21] | AlphaFold's predicted Local Distance Difference Test; per-residue model confidence. | >90: High confidence. >70: Confident. <50: Low confidence. |

| pTM [21] | Predicted Template Modeling score; global fold confidence metric. | Closer to 1.0 indicates a more correct overall fold. |

| RMSD [23] | Root Mean Square Deviation of atomic positions between predicted and target structures. | Lower values indicate better structural agreement. <2.0 Ã… for high accuracy. |

| FAPE Loss [23] | Frame Aligned Point Error; local structural loss function used in AF2 training and inversion. | Minimized during AF2-design; indicates how well the design matches the target scaffold. |

| Sequence Recovery | Percentage of native sequence residues recovered in a designed protein when using a natural template. | Measures design accuracy in fixed-backbone design. |

| Predicted ΔΔG | Predicted change in folding free energy relative to a wild-type or reference structure. | Negative values indicate more stable designs. |

| Boltz-2 Affinity Corr. [10] | Correlation between Boltz-2 predicted binding affinities and experimental values. | ~0.6 correlation with experiment, rivaling more costly physics-based simulations. |

Application Notes in Drug Discovery

Generative protein design is having a direct impact on pharmaceutical R&D by accelerating the discovery of therapeutic modalities.

Rational Antibody and Therapeutic Protein Design: The accurate prediction of protein-protein interfaces with AlphaFold 3 enables the design of antibodies and other biologics against specific epitopes. Designers can generate sequences for these scaffolds with tools like ProteinMPNN and RFAntibody, then validate binding complexes in silico, drastically reducing the need for initial animal immunization or large-scale display library screening [10] [26].

Targeting Previously Intractable Systems: AlphaFold 3's ability to model complexes of proteins, DNA, RNA, and small molecules (ligands) provides a holistic view of a drug target's biological context. For instance, designing a small molecule to disrupt a specific protein-DNA interaction becomes feasible when the complex structure can be accurately predicted [10] [26]. This allows for structure-based drug design against target classes previously deemed "undruggable."

A Practical Case Study: TIM-3 Inhibitor Design: Isomorphic Labs demonstrated the application of AlphaFold 3 in rational drug design for the TIM-3 target. They input the protein sequence and the SMILES string of a ligand, and AlphaFold 3 accurately predicted the binding mode and revealed a previously uncharacterized pocket, matching later experimental structures. This shows how generative structure prediction can directly guide the optimization of small-molecule drug candidates by visualizing their interaction with the target before synthesis [26].

Understanding the Protein Functional Universe and the Combinatorial Challenge

The functional sequence landscape of a protein represents the set of all amino acid sequences capable of carrying out a specific biological activity. This landscape is astronomically vast; for a typical protein, the total number of possible amino acid sequences is so large that exhaustive experimental exploration remains impossible. For example, evaluating all combinatorial mutations at just 27 residue positions on the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein's receptor-binding domain defines a theoretical search space of approximately 1.3×10³ⵠsequences and more than 5×10â¸â· side-chain conformations—a number greater than the number of atoms in the observable universe [27].

This combinatorial explosion represents the fundamental challenge in protein engineering: navigating an almost infinite possibility space to identify novel sequences with desired functions. Table 1 quantifies this complexity by breaking down the elements of the combinatorial challenge.

Table 1: The Combinatorial Protein Design Challenge

| Aspect of Complexity | Scale/Example | Implication for Protein Engineering |

|---|---|---|

| Theoretical Sequence Space | >10³ⵠsequences for 27 positions [27] | Impossible to explore exhaustively with brute-force methods. |

| Functional Sequence Landscape | Substantially reduced vs. total possible landscape [27] | Defines a tractable, yet still vast, search space for functional variants. |

| Epistatic Interactions | Non-linear effects of combined mutations [27] | Prevents accurate prediction of combinatorial mutations from individual mutation data. |

| Experimentally Confirmed Gold Standards | Sparse even in well-studied organisms (e.g., ~20% of S. cerevisiae genes lack annotations) [28] | Limits the supervised training data for machine learning models. |

| Functionally Dark Proteins | ~34% of UniRef50 clusters lack substantial functional annotation [29] | Represents a vast reservoir of unexplored natural protein diversity. |

Computational Frameworks for Navigating Sequence Space

AI-Driven Complete Combinatorial Enumeration

The Complete Combinatorial Mutational Enumeration (CCME) approach leverages artificial intelligence to define an entire functional sequence landscape in silico. This method utilizes a 3D protein structure and a pairwise decomposable energy function with the cost function network prover Toulbar2 to systematically discard unfit sequences and retain the exact ensemble of all functional sequences within a defined energy threshold [27].

Protocol 1: CCME for Functional Landscape Enumeration

- Input Structure: Begin with a high-resolution 3D structure of the protein or protein complex of interest (e.g., ACE2:RBD complex, PDB: 6M0J) [27].

- Define Search Parameters:

- Specify the residue positions for combinatorial mutation.

- Define the energy threshold for functional sequences (e.g., within 8 kcal/mol of the global energy minimum for binding).

- Set a stability cutoff (e.g., < 1 kcal/mol increase in folding energy).

- Sequence Enumeration with Toulbar2: Execute the enumeration to compute an exhaustive list of variant sequences meeting the energy and stability criteria. This step systematically prunes non-functional sequences.

- Fitness Landscape Analysis: Model the enumerated sequences as a network where nodes are sequences and edges connect single-mutation neighbors. Identify locally optimal sequences within this landscape.

- Cluster and Select: Cluster optimal sequences by similarity (e.g., using MMseqs2) and select medoid sequences from each cluster for downstream experimental characterization [27].

Generative AI for De Novo Protein Design

Generative AI models have emerged as powerful tools for creating novel protein structures and sequences beyond those found in nature. Unlike enumeration approaches, these models learn the underlying distribution of natural protein structures and can sample from this distribution to generate new, plausible designs.

The RFdiffusion and ProteinMPNN pipeline represents the current state-of-the-art:

- RFdiffusion: A diffusion model that iteratively denoises a cloud of atoms or a starting scaffold to generate novel protein backbones tailored for a specific function, such as binding a target [30] [31].

- ProteinMPNN: A sequence design model that, given a backbone structure, predicts an amino acid sequence that will fold into that structure [30].

Protocol 2: De Novo Design with RFdiffusion and ProteinMPNN

- Define Objective: Specify the design goal (e.g., create a binder for a specific helical peptide hormone).

- Scaffold Library Generation (Optional): Generate initial structural scaffolds using non-ML methods or existing folds as starting points for partial diffusion [31].

- Partial Diffusion with RFdiffusion: Use RFdiffusion in "partial" or "inpainting" mode, holding the target (e.g., the peptide) fixed while denoising the scaffold to form a complementary binding interface. Generate thousands of designs [31].

- Sequence Design with ProteinMPNN: For each generated backbone, run ProteinMPNN to design a corresponding amino acid sequence.

- In Silico Validation: Filter designs by structural metrics. A key validation step is to process the generated sequences with a structure prediction network like AlphaFold2 or RosettaFold2 and measure the similarity between the designed and predicted structures (pTM > 0.5, IDDT > 0.6 are common thresholds) [31].

- Iterative Redesign: Use the results from initial rounds to inform subsequent design cycles, potentially fine-tuning the models on successful designs.

Application Notes: From Prediction to Validation

Application Note: Engineering High-Affinity Binding Proteins

A landmark study demonstrated the design of proteins binding to human hormones (e.g., glucagon, PTH) with exceptional affinity, achieving what is believed to be the highest reported binding affinity for a computer-generated biomolecule [30].

Experimental Workflow & Validation:

- Computational Design: The RFdiffusion/ProteinMPNN pipeline was used to generate designs targeting helical peptides.

- Biosensor Integration: High-affinity binders were grafted into a lucCage biosensor system.

- Performance: The best biosensor for Parathyroid Hormone (PTH) showed a 21-fold increase in bioluminescence upon target binding [30].

- Robustness Testing: Designed proteins retained binding ability after exposure to high heat, a crucial attribute for real-world applications [30].

- Sensitivity: Mass spectrometry confirmed binding to low-concentration peptides in human serum, demonstrating diagnostic potential [30].

Application Note: Mapping Escape Mutants in Viral Evolution

The CCME method was applied to the ACE2 binding site of the SARS-CoV-2 spike RBD, enumerating 4.5 million functional sequence variants and clustering them into 59 representative "Potential Variants" (PVs) [27].

Key Findings:

- The PVs contained 10-15 amino acid changes each (over 40% of interface residues).

- 11 of 59 PVs retained ACE2 binding capability, with 8 binding at levels comparable to the native strain.

- Pseudovirus assays confirmed that selected PV RBDs could mediate host cell entry.

- Critically, these designed variants were shown to escape neutralization by monoclonal antibodies, providing a map of potential evolutionary pathways [27].

Table 2: Experimentally Validated AI-Designed Proteins

| Application | Computational Method | Experimental Validation & Key Result |

|---|---|---|

| High-Affinity Peptide Binders [30] | RFdiffusion + ProteinMPNN | Biosensor showed 21-fold activation; retained function after heating. |

| SARS-CoV-2 RBD Variants [27] | CCME (Toulbar2) | 8/59 designs bound ACE2; variants mediated cell entry and escaped antibodies. |

| CRISPR Activators [32] | Combinatorial Library Screening | Identified potent activators (MHV, MMH) with enhanced activity and reduced toxicity. |

| Stability Prediction [33] | QresFEP-2 (FEP Protocol) | Accurate prediction of ΔΔG for ~600 mutations across 10 protein systems. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Success in combinatorial protein design relies on a suite of computational and experimental tools. Table 3 details key reagents and their functions in a typical design-validate pipeline.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Combinatorial Protein Design

| Reagent / Software / Method | Function in the Pipeline | Key Features / Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Toulbar2 [27] | Exact combinatorial sequence enumeration within an energy threshold. | Guarantees finding all sequences meeting criteria; avoids sampling bias. |

| RFdiffusion [30] [31] | Generative AI for creating novel protein backbone structures. | Can be conditioned on target motifs (e.g., binding sites); requires substantial GPU resources. |

| ProteinMPNN [30] [31] | Sequence design for a given backbone structure. | Fast, robust, and produces highly designable sequences. |

| AlphaFold2 / RosettaFold2 [31] | In silico validation of designed protein structures. | Used to compute pTM, IDDT scores to assess design quality (pTM > 0.5 is a common filter). |

| Yeast Surface Display [27] | High-throughput screening of protein variants for binding. | Links genotype to phenotype; enables FACS-based enrichment of binders. |

| Biolayer Interferometry (BLI) [27] | Label-free measurement of binding affinity and kinetics. | Provides quantitative KD values for designed binders without purification. |

| Pseudovirus Particles [27] | Safe, functional assay for viral protein function (e.g., cell entry). | Recapitulates key steps of viral infection in a BSL-2 setting. |

| Free Energy Perturbation (QresFEP-2) [33] | Physics-based calculation of mutational effects on stability/binding. | High accuracy for ΔΔG prediction; computationally intensive but robust. |

| Antitumor agent-181 | Antitumor agent-181, MF:C23H18F3N3O3, MW:441.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Endoxifen-d5 | Endoxifen-d5, MF:C25H27NO2, MW:378.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Yeast Display Binding Assay for Designed RBDs

This protocol is adapted from the CCME study for testing the function of designed SARS-CoV-2 RBD variants [27].

Materials:

- Saccharomyces cerevisiae strain (e.g., EBY100).

- pCT-Con plasmid for AGA2 fusion surface expression.

- Synthesized genes encoding designed RBD variants.

- Purified Fc-ACE2 fusion protein.

- Fluorescently labeled anti-human Fc secondary antibody.

- FACS sorter.

Method:

- Cloning and Transformation: Clone synthesized RBD variant genes into the pCT-Con vector and transform into yeast competent cells.

- Induction of Expression: Grow transformed yeast cultures in selective media at 30°C to an OD₆₀₀ of ~2.0. Induce protein expression by transferring cells to induction media (SG-CAA) and incubate at 20°C for 24-48 hours.

- Binding Assay: a. Harvest ~1×10ⶠinduced yeast cells by centrifugation. b. Resuspend cells in PBSF (PBS + 1% BSA) containing a range of concentrations of Fc-ACE2 (e.g., 1 nM to 40 nM). c. Incubate for 1 hour at room temperature with gentle rotation. d. Wash cells twice with PBSF to remove unbound Fc-ACE2. e. Incubate cells with a fluorescently labeled anti-human Fc antibody on ice for 30 minutes in the dark. f. Wash cells twice and resuspend in PBSF for analysis.

- FACS Analysis and Sorting: Analyze yeast cells using a flow cytometer. The binding affinity can be assessed by the shift in fluorescence intensity across different Fc-ACE2 concentrations. Gate the positive population for binding.

Protocol: In Silico Validation with AlphaFold2

This protocol is critical for filtering generated designs before costly experimental testing [31].

Materials:

- FASTA files of sequences generated by ProteinMPNN.

- AlphaFold2 or ColabFold installation (local or cloud-based).

- Computing environment with GPU acceleration.

Method:

- Structure Prediction: Run AlphaFold2 in a no-template mode (

--db_preset=reduced_dbsor--template_mode=nonein ColabFold) for each designed sequence. Generate 5 models per sequence. - Metrics Extraction: For the top-ranked model (by pLDDT), extract key quality metrics:

- pLDDT (per-residue confidence score): A value > 90 indicates high confidence, > 70 indicates good confidence. The average pLDDT is a good overall metric.

- pTM (predicted Template Modeling score): Measures the global fold confidence. A pTM > 0.5 is often used as a passable threshold for novel designs.

- pLDDT at the interface: Ensure residues in the designed binding interface have high local confidence.

- Structural Alignment: Superimpose the AlphaFold2-predicted structure onto the original RFdiffusion-generated backbone using a tool like PyMOL or ChimeraX. Calculate the Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD) of the Cα atoms.

- Filtering: Designs that meet the following criteria are prioritized for experimental testing:

- High average pLDDT (> 70-80).

- High pTM score (> 0.5-0.6).

- Low RMSD (< 1.0-2.0 Ã…) between the predicted and designed structures, indicating the sequence is likely to fold as intended.

Architectures in Action: A Deep Dive into Generative Models and Their Real-World Applications

The field of protein design is undergoing a revolutionary transformation, moving from evolutionary-inspired approaches to first-principle rational engineering powered by generative artificial intelligence (AI). This paradigm shift enables the creation of novel bioactive molecules and functional proteins unbound by known structural templates and evolutionary constraints [34] [35]. Among the most impactful developments are two complementary approaches: ProGen, a language model for functional sequence generation, and RFdiffusion, a structure-based model for de novo protein design. These systems represent foundational technologies in the modern computational biologist's toolkit, enabling the programmable design of proteins with tailored functionalities for therapeutic, diagnostic, and synthetic biology applications [36].

ProGen operates primarily in sequence space, leveraging patterns learned from millions of natural protein sequences to generate novel, functional sequences. In contrast, RFdiffusion operates in structure space, generating novel protein backbones and complexes that can then be filled with sequences using complementary tools. Together, these platforms enable both sequence-first and structure-first design strategies, offering researchers complementary pathways to address diverse protein engineering challenges [36] [37].

ProGen: Engineering Functional Protein Sequences

Core Architecture and Mechanism

ProGen is an autoregressive language model based on the Transformer architecture, trained on millions of natural protein sequences from diverse families [36]. Unlike masked language models that learn to predict randomly omitted tokens from their context, autoregressive models generate sequences token-by-token from beginning to end, making them particularly suited for de novo generation tasks. ProGen treats amino acid sequences as sentences in the "language of life," learning the statistical patterns and syntactic rules that govern functional protein sequences across evolutionary lineages [36].

The model's training incorporates control tags specifying protein family, biological function, and other properties, enabling conditional generation of sequences with predefined characteristics. This capability allows researchers to steer sequence generation toward particular functional classes, essentially "programming" protein properties through prompt engineering [36]. Recent advancements have expanded ProGen's architecture to include structural awareness, with models like DS-ProGen integrating both backbone geometry and surface-level representations through dual-structure encoders [37].

Performance Metrics and Benchmarking

Table 1: Performance Benchmarks for Protein Language Models

| Model | Architecture | Primary Application | Key Metric | Performance Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ProGen | Autoregressive Transformer | Functional sequence generation | Diversity of generated sequences | High (spans diverse families) |

| ESM-2 | Masked Language Model | Sequence representation learning | Structural prediction accuracy | ~0.96Ã… RMSD (250 residues) |

| DS-ProGen | Dual-structure Transformer | Inverse protein folding | Sequence recovery rate | 61.47% (PRIDE benchmark) |

| ProteinMPNN | Graph Neural Network | Sequence design for structures | Sequence recovery rate | ~60% (native-like sequences) |

ProGen has demonstrated remarkable capability in generating functional protein sequences that diverge significantly from natural homologs while maintaining structural integrity and function. In benchmark evaluations, the model produces sequences with native-like properties and has been experimentally validated to generate functional enzymes and binding proteins [36]. The DS-ProGen variant, which incorporates structural information, achieves state-of-the-art performance on inverse folding tasks, demonstrating the synergistic advantage of combining sequence-based and structure-based approaches [37].

Application Protocol: Generating Functional Enzymes

Protocol Title: De Novo Generation of Functional Enzyme Sequences Using ProGen

Purpose: To generate novel enzyme sequences with potential catalytic activity for a specific biochemical reaction.

Materials and Reagents:

- ProGen model (publicly available weights)

- High-performance computing environment with GPU acceleration

- Sequence alignment tools (e.g., BLAST, HMMER)

- Molecular dynamics simulation software (e.g., GROMACS, OpenMM)

- Heterologous expression system (E. coli, yeast, or cell-free)

- Activity assays specific to target enzyme function

Procedure:

Prompt Design and Conditioning:

- Define functional constraints including enzyme commission number, catalytic mechanism, and desired organismal optimization (e.g., thermostability)

- Format control tags as:

[Family=Enzyme] [EC=1.1.1.1] [Function=Alcohol_dehydrogenase] [Stability=Thermostable]

Sequence Generation:

- Initialize generation with start token and control tags

- Sample sequences using temperature-based sampling (T=0.7-1.0) to balance diversity and quality

- Generate 1,000-10,000 candidate sequences for screening

In Silico Validation:

- Filter sequences by length, composition, and complexity

- Perform multiple sequence alignment against natural families to verify novelty

- Predict structures using AlphaFold2 or ESMFold to confirm fold integrity

- Run molecular dynamics simulations to assess stability

Experimental Validation:

- Synthesize top 50-100 candidates codon-optimized for expression system

- Express in suitable host system and purify proteins

- Characterize catalytic efficiency (kcat/Km), substrate specificity, and stability

- For successful designs, determine crystal structures to validate computational predictions

Troubleshooting:

- If generated sequences show poor expression, adjust conditional tags to include solubility constraints

- If catalytic activity is low, employ iterative optimization with focused libraries around active site residues

- If structural predictions disagree with experimental data, fine-tune on structural constraints

RFdiffusion: De Novo Structure-Based Design

Theoretical Foundations and Algorithmic Innovation

RFdiffusion belongs to the class of score-based denoising diffusion probabilistic models (DDPMs) that learn to iteratively transform random noise into coherent protein structures through a reverse diffusion process [34]. The model builds on the architectural framework of RoseTTAFold, which provides a robust representation of protein geometry through coordinates of Cα atoms and their associated orientation frames (N-Cα-C) for each residue [38].

The diffusion process occurs over a fixed number of timesteps (T), during which the model is trained to predict the de-noised structure (pXâ‚€) at each step, minimizing the mean squared error between the predicted and true structure (Xâ‚€) [39]. During inference, RFdiffusion starts from a completely random distribution of residues (X_T) and iteratively refines this distribution through learned denoising steps to generate novel protein structures that satisfy user-defined constraints [38] [39].

Recent advancements in RFdiffusion have expanded its capabilities through specialized fine-tuning:

- RFdiffusion3 implements all-atom co-diffusion, simultaneously generating protein backbones, sidechains, and complex interactions with ligands, DNA, and other biomolecules [38]

- RFantibody fine-tunes the network on antibody complex structures, enabling de novo design of complementarity-determining regions (CDRs) that target specific epitopes [39] [40]

- Flexible target fine-tuning enables targeting of intrinsically disordered proteins (IDPs) and regions (IDRs) by freely sampling both target and binder conformations [41]

Performance Benchmarks and Experimental Validation

Table 2: RFdiffusion Performance Across Design Challenges

| Design Challenge | RFdiffusion Variant | Success Rate | Affinity Range (Kd) | Experimental Validation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protein-small molecule binders | RFdiffusion All-Atom | High | nM-μM | Yes (crystal structures) |

| Intrinsically disordered proteins | Flexible target | ~60% | 3-100 nM | Yes (biolayer interferometry) |

| Antibody design (VHHs) | RFantibody | Moderate | tens-hundreds nM | Yes (cryo-EM confirmation) |

| Enzyme active sites | RFdiffusion3 | 90% successful scaffolding | N/A | Yes (catalytic efficiency) |

| Protein-DNA interactions | RFdiffusion3 | High diversity | Low micromolar (e.g., 5.9 μM) | Yes (binding confirmed) |

RFdiffusion has demonstrated remarkable performance across diverse design challenges. In targeting intrinsically disordered proteins, the platform generated binders to amylin, C-peptide, and other IDPs with dissociation constants ranging from 3 to 100 nM [41]. For enzyme design, RFdiffusion3 successfully scaffolded catalytic motifs in 90% of tested cases, with the best designs achieving catalytic efficiencies (kcat/Km) of 3557 Mâ»Â¹sâ»Â¹ for a cysteine hydrolase [38]. The atomic-level accuracy of designs has been confirmed through high-resolution cryo-EM structures of designed antibodies, verifying precise epitope targeting [39].

Application Protocol: Designing Binders for Intrinsically Disordered Proteins

Protocol Title: De Novo Binder Design for Intrinsically Disordered Targets Using RFdiffusion

Purpose: To generate high-affinity, structured protein binders that target intrinsically disordered proteins or protein regions.

Materials and Reagents:

- RFdiffusion installation (with flexible target fine-tuning)

- ProteinMPNN for sequence design

- AlphaFold2 or AlphaFold3 for structure validation

- Biolayer interferometry (BLI) or surface plasmon resonance (SPR) system

- Fluorescence polarization/detection equipment

- Mammalian cell culture system for cellular validation

Procedure:

Target Specification and Preparation:

- Obtain target IDP sequence and define target length (typically 30-50 residues)

- Run disorder prediction algorithms (IUpred3, Jpred4) to confirm disordered regions

- No structural information is required—input is sequence-only

Binder Generation with Two-Sided Partial Diffusion:

- Use flexible target fine-tuned RFdiffusion with sequence-only input

- Implement two-sided partial diffusion to sample varied target and binder conformations simultaneously

- Generate 500-1,000 backbone designs with diverse architectural motifs (αβ, αβL, αα)

- Select designs with high shape complementarity and extensive interface interactions

Sequence Design and Filtering:

- Process generated backbones with ProteinMPNN to design sequences

- Filter designs using AlphaFold2 initial guess for complex formation

- Select top 100-200 designs with highest predicted confidence metrics (pLDDT > 80)

Experimental Characterization:

- Express and purify top 50-100 designs using E. coli or mammalian systems

- Measure binding affinity using BLI/SPR with serial dilutions (typically 1 nM - 10 μM)

- Validate binding specificity through competition assays

- For confirmed binders, determine thermostability using circular dichroism

- Conduct cellular imaging to verify intracellular target engagement

- For therapeutic candidates, evaluate functional consequences (e.g., inhibition of amyloid formation)

Troubleshooting:

- If initial designs show weak binding, employ two-sided partial diffusion to improve shape complementarity

- If expression yields are low, optimize sequences using structure-based stability calculations

- If binders show aggregation, incorporate negative design principles during sequence optimization

Integrated Workflow: From Design to Validation

The most powerful applications of generative protein design emerge from integrating sequence-based and structure-based approaches in a unified workflow. The following diagram illustrates a comprehensive pipeline combining ProGen and RFdiffusion for functional protein design:

Integrated Workflow for Generative Protein Design

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Generative Protein Design

| Category | Specific Tool/Reagent | Function/Purpose | Access Type |

|---|---|---|---|

| Generative Models | ProGen (Family) | Conditional protein sequence generation | Open source |

| RFdiffusion Suite | De novo protein structure generation | Open source | |

| DS-ProGen | Dual-structure inverse protein folding | Open source | |

| Validation Tools | ProteinMPNN | Sequence design for structural scaffolds | Open source |

| AlphaFold2/3 | Structure prediction validation | Partially restricted | |

| RoseTTAFold2 | Complex structure prediction | Open source | |

| Experimental Systems | Yeast Surface Display | High-throughput binder screening | Commercial/Wet-lab |

| Biolayer Interferometry | Binding affinity quantification | Commercial | |

| Cell-free Expression | Rapid protein synthesis | Commercial/Wet-lab | |

| Specialized Frameworks | RFantibody | De novo antibody design | Open source |

| IgGM | Comprehensive antibody design suite | Open source with restrictions | |

| Mosaic | General protein design framework | Open source |

The integration of ProGen and RFdiffusion represents a paradigm shift in protein engineering, moving the field from evolutionary imitation to first-principle design. These platforms have demonstrated remarkable success across diverse applications, from developing therapeutic candidates for challenging targets like IDPs and GPCRs to creating enzymes with novel catalytic functions [41] [40].

The future of generative protein design lies in several key directions: increased atomic-level precision through models like RFdiffusion3 [38]; tighter integration of sequence and structure generation in unified frameworks [37]; and the development of closed-loop experimental validation systems that feed back into model improvement [35]. As these technologies mature, they promise to accelerate the development of novel biologics, enzymes for sustainable chemistry, and modular components for synthetic biology, ultimately enabling the programmable design of biological function from first principles.

The field of protein design is undergoing a profound transformation, moving beyond traditional methods that treat sequence, structure, and function as separate design problems. The emergence of unified AI frameworks represents a paradigm shift toward integrated co-design, where these elements are generated simultaneously within a single model. This approach transcends the limitations of conventional pipeline-based methods, which often propagate errors between sequential stages and fail to capture the complex interdependencies between sequence, structure, and biological function [2] [12].