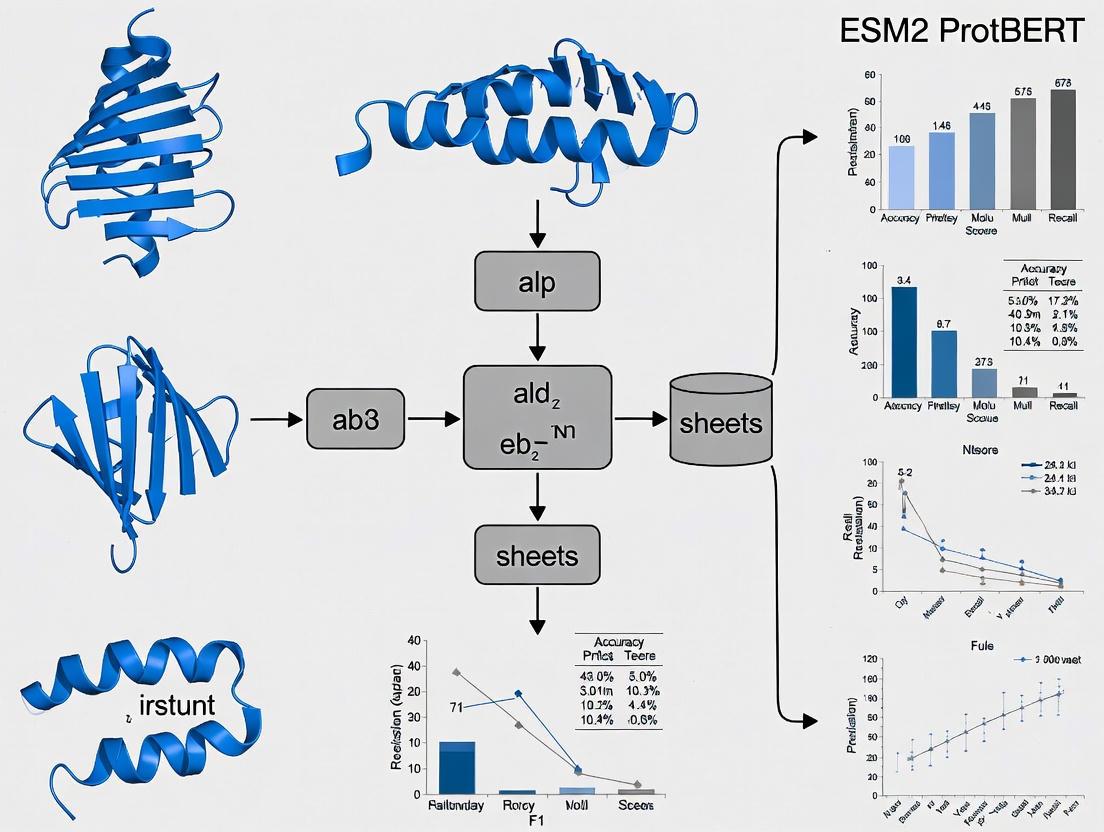

ESM-2 vs ProtBERT: A Comprehensive Performance Comparison for Protein Function Prediction and Biomedical Applications

This comprehensive analysis compares two leading protein language models—ESM-2 and ProtBERT—across multiple biological prediction tasks including enzyme function annotation, cell-penetrating peptide prediction, and protein-protein interactions.

ESM-2 vs ProtBERT: A Comprehensive Performance Comparison for Protein Function Prediction and Biomedical Applications

Abstract

This comprehensive analysis compares two leading protein language models—ESM-2 and ProtBERT—across multiple biological prediction tasks including enzyme function annotation, cell-penetrating peptide prediction, and protein-protein interactions. Drawing from recent peer-reviewed studies, we examine their architectural foundations, methodological applications, optimization strategies, and comparative performance against traditional tools like BLASTp. The analysis reveals that while both models offer significant advantages over conventional methods, ESM-2 generally outperforms ProtBERT in challenging annotation scenarios, particularly for enzymes with low sequence similarity. However, fusion approaches combining both models demonstrate state-of-the-art performance, suggesting complementary strengths that can be leveraged for advanced biomedical research and drug development applications.

Understanding ESM-2 and ProtBERT: Architectural Foundations and Biological Context

The application of the Transformer architecture, originally developed for natural language processing (NLP), to protein sequences represents a paradigm shift in computational biology. Protein language models (pLMs) like ESM-2 and ProtBERT treat amino acid sequences as textual sentences, enabling deep learning models to capture complex evolutionary, structural, and functional patterns from massive protein sequence databases. These models utilize self-supervised pre-training objectives, particularly masked language modeling (MLM), where the model learns to predict randomly masked amino acids within sequences, thereby internalizing fundamental principles of protein biochemistry without explicit supervision [1]. This approach has demonstrated remarkable emergent capabilities, with models progressively learning intricate mappings between sequence statistics and three-dimensional protein structures despite receiving no direct structural information during training [1].

The transfer of Transformer architecture to protein sequences has created unprecedented opportunities for predicting protein function, structure, and properties. Unlike traditional methods that rely on handcrafted features or resource-intensive multiple sequence alignments, pLMs can generate rich contextual representations directly from single sequences, enabling rapid biological insight [2] [3]. This technological advancement is particularly valuable for drug development professionals and researchers seeking to accelerate protein characterization, engineer novel enzymes, and identify therapeutic targets. Within this landscape, ESM-2 and ProtBERT have emerged as two leading architectural implementations with distinct strengths and performance characteristics across various biological tasks, making their comparative analysis essential for guiding model selection in research and development applications.

Architectural Foundations: ESM-2 and ProtBERT

ESM-2 (Evolutionary Scale Modeling-2)

ESM-2 builds upon the RoBERTa architecture, a refined variant of BERT that eliminates the next sentence prediction objective and employs dynamic masking during training. The model incorporates several key modifications to optimize it for protein sequences, including the implementation of rotary position embeddings (RoPE) to better model long-range dependencies in protein sequences, which often exceed the length of typical text sentences [1]. This architectural choice is particularly valuable for capturing interactions between distal residues that form three-dimensional contacts in protein structures. ESM-2 was pre-trained on 65 million unique protein sequences from the UniRef50 database using the masked language modeling objective, where approximately 15% of amino acids in each sequence were randomly masked and the model was trained to predict their identities based on contextual information [2] [1].

The scaling properties of ESM-2 demonstrate clear trends of improving structural understanding with increasing model size. Analyses reveal that as ESM-2 scales from 8 million to 15 billion parameters, long-range contact precision increases substantially from 0.16 to 0.54 (representing a 238% relative gain), while CASP14 TM-score rises from 0.37 to 0.55 (49% relative gain), indicating atomic-level structure quality improves with model scale [1]. Simultaneously, perplexity measurements decline from 10.45 to 6.37, confirming that language modeling of sequences enhances across scaling tiers. Critically, proteins exhibiting large perplexity gains also show substantial contact prediction gains (NDCG = 0.87), evidencing a tight coupling between sequence modeling improvement and structure prediction capability [1].

ProtBERT

ProtBERT adopts the original BERT architecture with both masked language modeling (MLM) and next sentence prediction (NSP) pre-training objectives, though the NSP task is adapted for protein sequences by predicting whether two sequence fragments originate from the same protein [4]. This dual-objective approach aims to capture both local contextual relationships and global protein-level information. ProtBERT was pre-trained on a composite dataset including sequences from UniRef100 and the BFD (Big Fantastic Database), encompassing a broader evolutionary diversity compared to ESM-2's training corpus [4]. The model utilizes absolute position embeddings rather than the relative position scheme employed by ESM-2, which may impact its ability to generalize to sequences longer than those encountered during training.

While ProtBERT demonstrates strong performance on various protein function prediction tasks, its architectural foundation hews more closely to the original BERT implementation without the protein-specific modifications seen in ESM-2. This distinction potentially contributes to the performance differences observed across various biological applications, particularly in structure-related predictions where ESM-2 generally excels. However, ProtBERT remains highly competitive for certain functional annotation tasks, especially when fine-tuned on specific prediction objectives rather than used solely as a feature extractor [4].

Performance Comparison Across Biological Tasks

Enzyme Function Prediction

Enzyme Commission (EC) number prediction represents a fundamental challenge in functional bioinformatics, with implications for metabolic engineering, drug target identification, and genome annotation. A comprehensive 2025 study evaluated ESM-2, ESM-1b, and ProtBERT as feature extractors for EC number prediction, comparing their performance against traditional BLASTp homology searches [4]. The experimental protocol involved extracting embedding representations from each model's final hidden layer, applying global mean pooling to generate sequence-level features, and training fully connected neural networks for multi-label EC number classification using UniProtKB data with rigorous clustering to prevent homology bias.

Table 1: Performance Comparison for Enzyme Function Prediction

| Model | Overall Accuracy | Performance on Low-Identity Sequences (<25% identity) | Key Strengths |

|---|---|---|---|

| ESM-2 | 0.842 (F1-score) | 0.781 (F1-score) | Best for difficult annotation tasks and enzymes without homologs |

| ProtBERT | 0.819 (F1-score) | 0.752 (F1-score) | Competitive on well-characterized enzyme families |

| ESM-1b | 0.831 (F1-score) | 0.763 (F1-score) | Moderate performance across all categories |

| BLASTp | 0.849 (F1-score) | 0.601 (F1-score) | Superior for sequences with clear homologs, fails without homology |

The results revealed that although BLASTp provided marginally better overall performance, ESM-2 stood out as the best model among pLMs, particularly for challenging annotation tasks and enzymes without close homologs [4]. The performance gap between ESM-2 and BLASTp widened significantly when sequence identity to known proteins fell below 25%, demonstrating the particular value of ESM-2 for characterizing novel enzyme families with limited evolutionary relationships to characterized proteins. The study concluded that while pLMs still require further development to completely replace BLASTp in mainstream annotation pipelines, they provide complementary strengths and significantly enhance prediction capabilities when used in combination with alignment-based methods [4].

Protein Crystallization Propensity Prediction

Protein crystallization represents a critical bottleneck in structural biology, with successful crystallization rates typically ranging between 2-10% despite extensive optimization efforts [2]. A 2025 benchmarking study evaluated multiple pLMs for predicting protein crystallization propensity based solely on amino acid sequences, comparing ESM-2 variants against other models including Ankh, ProtT5-XL, ProstT5, xTrimoPGLM, and SaProt [2]. The experimental methodology utilized the TRILL platform to generate embedding representations from each model, followed by LightGBM and XGBoost classifiers with hyperparameter tuning. Models were evaluated on independent test sets from SwissProt and TrEMBL databases using AUPR (Area Under Precision-Recall Curve), AUC (Area Under ROC Curve), and F1 scores as primary metrics.

Table 2: Performance Comparison for Protein Crystallization Prediction

| Model | Parameters | AUC | AUPR | F1 Score | Inference Speed |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ESM-2 3B | 3 billion | 0.912 | 0.897 | 0.868 | Medium |

| ESM-2 650M | 650 million | 0.904 | 0.883 | 0.851 | Fast |

| ProtT5-XL | - | 0.889 | 0.872 | 0.839 | Slow |

| Ankh-Large | - | 0.881 | 0.861 | 0.828 | Medium |

| Traditional Methods | - | 0.84-0.87 | 0.82-0.85 | 0.80-0.83 | Variable |

The results demonstrated that ESM-2 models with 30 and 36 transformer layers (150 million and 3 billion parameters respectively) achieved performance gains of 3-5% across all evaluation metrics compared to other pLMs and state-of-the-art sequence-based methods like DeepCrystal, ATTCrys, and CLPred [2]. Notably, the ESM-2 650M parameter model provided an optimal balance between prediction accuracy and computational efficiency, falling only slightly behind the 3 billion parameter variant while offering significantly faster inference times. This advantage persisted across different evaluation datasets, including balanced test sets and more challenging real-world scenarios from TrEMBL, highlighting ESM-2's robustness for practical applications in structural biology pipelines.

Cell-Penetrating Peptide Prediction

Cell-penetrating peptides (CPPs) have emerged as promising vehicles for drug delivery, necessitating accurate computational methods for their identification. A 2024 study proposed FusPB-ESM2, a fusion framework that combines features from both ProtBERT and ESM-2 to predict cell-penetrating peptides [5]. The experimental protocol extracted feature representations from both models separately, then fused these embeddings before final prediction through a linear mapping layer. The model was evaluated on public CPP datasets using AUC (Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve) as the primary metric, with comparison against established methods including CPPpred, SVM-based predictors, CellPPDMod, CPPDeep, SiameseCPP, and MLCPP2.0.

The results demonstrated that the fusion approach achieved state-of-the-art performance with an AUC of 0.92, outperforming individual models and all existing methods [5]. When evaluated individually, ESM-2 slightly outperformed ProtBERT (0.89 vs. 0.87 AUC), suggesting that ESM-2's representations captured more discriminative features for this specific classification task. However, the fusion of both models provided complementary information that enhanced predictive accuracy, indicating that while these architectures share fundamental similarities, they learn partially orthogonal representations that can be synergistically combined for improved performance on specialized prediction tasks.

Protein-Protein Interaction Prediction

Protein-protein interactions (PPIs) form the backbone of cellular signaling and regulatory networks, making their accurate prediction crucial for understanding disease mechanisms and identifying therapeutic interventions. The ESM2_AMP framework, developed in 2025, leverages ESM-2 embeddings for interpretable prediction of binary PPIs [6]. This approach employs a dual-level feature extraction strategy, generating global representations through mean pooling of full-length sequences, special token features from [CLS] and [EOS] tokens, and segment-level representations by dividing sequences into ten equal parts. These features are fused using multi-head attention mechanisms before final prediction with a multilayer perceptron.

The model was rigorously evaluated on multiple datasets including the human Pandataset, multi-species datasets, and the gold-standard Bernett dataset with strict partitioning to prevent data leakage [6]. ESM2AMP achieved high accuracy (0.94 on human PPIs) while providing enhanced interpretability through attention mechanisms that highlighted biologically relevant sequence segments corresponding to known functional domains. This interpretability advantage represents a significant advancement over black-box prediction methods, as it enables researchers to not only predict interactions but also generate testable hypotheses about the molecular determinants of these interactions. The success of this framework underscores ESM-2's capacity to capture features relevant to higher-order protein functionality beyond individual protein properties.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standardized Transfer Learning Protocol

Across multiple studies, a consistent experimental methodology has emerged for evaluating pLM performance through transfer learning. The standard protocol involves: (1) Embedding Extraction: Generating sequence representations from the final hidden layer of pre-trained models; (2) Embedding Compression: Applying pooling operations (typically mean pooling) to create fixed-length representations; (3) Downstream Model Training: Using compressed embeddings as features for supervised learning with models like regularized regression, tree-based methods, or neural networks; and (4) Evaluation: Rigorous testing on held-out datasets with appropriate metrics for each task [7] [4] [2].

A critical methodological consideration involves embedding compression strategies. Research has systematically evaluated various approaches including mean pooling, max pooling, inverse Discrete Cosine Transform (iDCT), and PCA compression. Surprisingly, simple mean pooling consistently outperformed more complex compression methods across diverse biological tasks [7]. For deep mutational scanning data, mean pooling increased variance explained (R²) by 5-20 percentage points compared to alternatives, while for diverse protein sequences the improvement reached 20-80 percentage points [7]. This finding has important practical implications, establishing mean pooling as the recommended approach for most transfer learning applications and simplifying implementation pipelines.

Model Scaling Experiments

To evaluate the impact of model size on performance, researchers have conducted systematic comparisons across parameter scales. These experiments typically involve comparing multiple size variants of the same architecture (e.g., ESM-2 8M, 35M, 150M, 650M, 3B, 15B) on identical tasks to isolate the effect of parameter count from architectural differences [7]. The consistent finding across studies is that performance improves with model size but follows diminishing returns, with medium-sized models (100 million to 1 billion parameters) often providing the optimal balance between performance and computational requirements [7].

Notably, the relationship between model size and performance is modulated by dataset size. Larger models require more data to realize their full potential, and when training data is limited, medium-sized models frequently match or even exceed the performance of their larger counterparts [7]. This has important practical implications for researchers working with specialized protein families or experimental datasets where sample sizes may be constrained. In such scenarios, selecting a medium-sized model like ESM-2 650M or ESM C 600M provides nearly equivalent performance to the 15B parameter model while dramatically reducing computational requirements [7].

Experimental Workflow for Protein Function Prediction

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Protein Language Model Research

| Tool/Resource | Type | Function | Access |

|---|---|---|---|

| ESM-2 Model Series | Protein Language Model | Feature extraction for protein sequences, structure prediction | https://github.com/facebookresearch/esm |

| ProtBERT | Protein Language Model | Alternative embedding generation, fine-tuning for specific tasks | https://huggingface.co/Rostlab/prot_bert |

| TRILL Platform | Computational Framework | Democratizing access to multiple pLMs for property prediction | https://github.com/emmadebart/trill |

| UniProtKB | Database | Curated protein sequences and functional annotations | https://www.uniprot.org |

| PISCES Database | Database | Curated protein sequences for structural biology applications | http://dunbrack.fccc.edu/pisces/ |

| Deep Mutational Scanning Data | Experimental Dataset | Quantitative measurements of mutation effects for model validation | https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-021-04056-3 |

| 1,5-Dodecanediol | 1,5-Dodecanediol, CAS:20999-41-1, MF:C12H26O2, MW:202.33 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| SARS-CoV-2-IN-9 | SARS-CoV-2-IN-9, MF:C15H14Cl2N4O3, MW:369.2 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Practical Implementation Considerations

Computational Requirements and Efficiency

The computational demands of pLMs vary significantly based on model size and application scenario. While the largest ESM-2 variant (15B parameters) requires substantial GPU memory and inference time, medium-sized models like ESM-2 650M provide a favorable balance, being "many times smaller" than their largest counterparts while falling "only slightly behind" in performance [7]. This makes them practical choices for most research laboratories without specialized AI infrastructure. For context, ESMFold, which builds upon ESM-2, achieves up to 60x faster inference than previous methods while maintaining competitive accuracy, highlighting the efficiency gains possible with optimized architectures [1].

Practical implementation also involves considering embedding extraction strategies. While per-residue embeddings are necessary for structure-related predictions, most function prediction tasks benefit from sequence-level embeddings obtained through pooling operations. The finding that mean pooling consistently outperforms more complex compression methods significantly simplifies implementation requirements [7]. Researchers can thus avoid computationally expensive compression algorithms while maintaining state-of-the-art performance for classification and regression tasks.

Data Requirements and Transfer Learning

The performance of pLMs is influenced by both model scale and dataset characteristics. When data is limited, medium-sized models perform comparably to, and in some cases outperform, larger models [7]. This relationship has important implications for practical applications: for high-throughput screening with large datasets, larger models may be justified, while for specialized tasks with limited training examples, medium-sized models provide better efficiency. Additionally, the fusion of features from multiple pLMs, as demonstrated in FusPB-ESM2, can enhance performance for specialized prediction tasks, suggesting an ensemble approach may be valuable when maximum accuracy is required [5].

Transformer Architecture for Protein Sequences

The comparative analysis of ESM-2 and ProtBERT reveals a nuanced landscape where architectural decisions, training methodologies, and application contexts collectively determine model performance. ESM-2 generally demonstrates superior capabilities for structure-related predictions and tasks requiring evolutionary insight, while ProtBERT remains competitive for specific functional annotation challenges. The emerging consensus indicates that medium-sized models (100M-1B parameters) frequently provide the optimal balance between performance and efficiency for most research applications, particularly when data is limited [7].

Future developments in protein language modeling will likely focus on several key areas: (1) enhanced model interpretability to bridge the gap between predictions and biological mechanisms [6]; (2) integration of multi-modal data including structural information and experimental measurements; and (3) development of efficient fine-tuning techniques to adapt general-purpose models to specialized biological domains. As these models continue to evolve, they will increasingly serve as foundational tools for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals seeking to decode the complex relationships between protein sequence, structure, and function. The systematic benchmarking and performance comparisons presented in this review provide a framework for informed model selection based on specific research requirements and computational constraints.

The application of large language models (LLMs) to protein sequences represents a paradigm shift in bioinformatics, enabling researchers to decode the complex relationships between protein sequence, structure, and function. Among these models, ESM-2 (Evolutionary Scale Modeling-2) from Meta AI has emerged as a state-of-the-art protein-specific framework that demonstrates exceptional capability in predicting protein structure and function directly from individual amino acid sequences [8]. This advancement is particularly significant given that traditional experimental methods for characterizing proteins are time-consuming and resource-intensive, leaving the vast majority of the over 240 million protein sequences in databases like UniProt without experimentally validated functions [3]. Protein language models like ESM-2 operate on a fundamental analogy: just as natural language models learn from sequences of words, protein language models learn from sequences of amino acids, treating the 20 standard amino acids as tokens in a biological vocabulary [9]. Through self-supervised pretraining on millions of protein sequences, these models capture evolutionary patterns, structural constraints, and functional motifs without requiring explicit structural or functional annotations [9] [3]. The ESM-2 framework builds upon the transformer architecture, which is particularly well-suited for protein modeling due to its ability to capture long-range dependencies between amino acids that may be far apart in the linear sequence but spatially proximate in the folded protein structure [9].

ESM-2 Architecture and Technical Implementation

Model Design and Scaling

ESM-2 implements a transformer-based architecture specifically optimized for protein sequences, with model sizes ranging from 8 million to 15 billion parameters [7] [8]. A key innovation in ESM-2 is the replacement of absolute position encoding with relative position encoding, which enables the model to generalize to amino acid sequences of arbitrary lengths and improves learning efficiency [5]. The model was pretrained on approximately 65 million non-redundant protein sequences from the UniRef50 database using a masked language modeling objective, where the model learns to predict randomly masked amino acids based on their context within the sequence [10] [8]. This self-supervised approach allows the model to internalize fundamental principles of protein biochemistry and evolutionary constraints without requiring labeled data. The ESM-2 framework also includes ESMFold, an end-to-end single-sequence 3D structure predictor that leverages the representations learned by ESM-2 to generate accurate atomic-level protein structures directly from sequence information [8]. Unlike traditional structure prediction methods that rely on multiple sequence alignments (MSAs) and homology modeling, ESMFold demonstrates that a single-sequence language model can achieve remarkable accuracy in structure prediction, significantly reducing computational requirements while maintaining competitive performance [8].

Access and Implementation

ESM-2 is accessible to researchers through multiple interfaces, including:

- Python library via pip installation (

fair-esm) - HuggingFace Transformers library for standardized access

- TorchHub for direct loading without local installation

- REST API for folding sequences via HTTP requests [8]

The framework provides pretrained models of varying sizes, allowing researchers to select the appropriate balance between performance and computational requirements for their specific applications [7].

Performance Comparison: ESM-2 vs. ProtBERT and Other Alternatives

Experimental Framework for Model Evaluation

Comprehensive evaluation of protein language models requires standardized datasets and benchmarking protocols across diverse biological tasks. In the critical domain of enzyme function prediction, studies have defined EC (Enzyme Commission) number prediction as a multi-label classification problem that incorporates promiscuous and multi-functional enzymes [4]. Experimental protocols typically involve training fully connected neural networks on embeddings extracted from various protein language models, then comparing their performance against traditional methods like BLASTp and models using one-hot encodings [4] [11]. For protein stability prediction, benchmark datasets such as Ssym, S669, and Frataxin are used to evaluate a model's ability to predict changes in protein thermodynamic stability (ΔΔG) caused by single-point variations [12]. Performance is typically measured using metrics including Pearson Correlation Coefficient (PCC), root mean squared error (RMSE), and accuracy (ACC) [12]. Embedding compression methods also play a crucial role in transfer learning applications, with studies systematically evaluating techniques like mean pooling, max pooling, and inverse Discrete Cosine Transform (iDCT) to reduce the dimensionality of embeddings while preserving critical biological information [7].

Comparative Performance in Enzyme Function Prediction

Table 1: Performance Comparison in EC Number Prediction

| Model | Overall Accuracy | Performance on Difficult Annotations | Performance Without Homologs | Key Strengths |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ESM-2 | High | Best | Best | Excellent for sequences with <25% identity to training data |

| ProtBERT | Competitive | Moderate | Moderate | Strong general performance |

| BLASTp | Slightly better than ESM-2 | Lower than ESM-2 | Poor | Relies on sequence homology |

| One-hot encoding models | Lower than LLM-based | Lower | Lower | Baseline performance |

In direct comparisons for Enzyme Commission number prediction, ESM-2 consistently emerges as the top-performing protein language model [4] [11]. While the traditional sequence alignment tool BLASTp provides marginally better results overall, ESM-2 demonstrates superior performance on difficult annotation tasks and for enzymes without homologs in reference databases [4] [11]. This capability is particularly valuable for annotating orphan enzymes that lack significant sequence similarity to well-characterized proteins. The performance advantage of ESM-2 becomes more pronounced when the sequence identity between the query and reference database falls below 25%, suggesting that language models capture fundamental biochemical principles that extend beyond evolutionary relationships [4]. Importantly, studies note that BLASTp and language models provide complementary predictions, with each method excelling on different subsets of EC numbers, indicating that ensemble approaches combining both methods can achieve superior performance than either method alone [4] [11].

Performance in Specialized Applications

Table 2: Performance Across Diverse Protein Tasks

| Application Domain | ESM-2 Performance | ProtBERT Performance | Superior Model |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell-penetrating peptide prediction | High accuracy in fusion models | High accuracy in fusion models | FusPB-ESM2 (fusion) performs best |

| Protein stability prediction (ΔΔG) | PCC = 0.76 on Ssym148 dataset | Not reported in studies | ESM-2 |

| DNA-binding protein prediction | Improved with domain-adaptive pretraining | Not specifically evaluated | ESM-DBP (adapted ESM-2) |

| Structure prediction | State-of-the-art single-sequence method | Less emphasis on structure | ESM-2 |

Beyond enzyme function prediction, ESM-2 demonstrates strong performance across diverse bioinformatics tasks. In protein stability prediction, the THPLM framework utilizing ESM-2 embeddings achieved a Pearson correlation coefficient of 0.76 on the antisymmetric Ssym148 dataset, outperforming most sequence-based and structure-based methods [12]. For DNA-binding protein prediction, domain-adaptive pretraining of ESM-2 on specialized datasets (creating ESM-DBP) significantly improved feature representation and prediction accuracy for DNA-binding proteins, transcription factors, and DNA-binding residues [10]. In cell-penetrating peptide prediction, a fusion model combining both ESM-2 and ProtBERT embeddings (FusPB-ESM2) achieved state-of-the-art performance, suggesting that these models capture complementary features that can be synergistically combined for specialized applications [5].

Impact of Model Size on Performance

Table 3: Model Size vs. Performance Trade-offs

| Model Category | Parameter Range | Performance | Computational Requirements | Recommended Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Small models | <100 million | Good with sufficient data | Low | Limited resources, small datasets |

| Medium models | 100M-1B | Excellent, nearly matches large models | Moderate | Most practical applications |

| Large models | >1 billion | Best overall | High | Maximum accuracy, ample resources |

The relationship between model size and performance follows nuanced patterns in protein language models. While the largest ESM-2 variant with 15 billion parameters achieves state-of-the-art performance on many tasks, medium-sized models (100 million to 1 billion parameters) provide an excellent balance between performance and computational requirements [7]. Surprisingly, in transfer learning scenarios with limited data, medium-sized models often perform comparably to or even outperform their larger counterparts [7]. This phenomenon is particularly relevant for researchers with limited computational resources, as models like ESM-2 650M and ESM C 600M deliver strong performance while being significantly more accessible than the 15B parameter version [7]. The optimal model size depends on specific factors including dataset size, protein length, and task complexity, with larger models showing greater advantages when applied to large datasets that can fully leverage their representational capacity [7].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standardized Evaluation Workflows

Diagram 1: EC Number Prediction Workflow

The experimental workflow for comparing protein language models typically begins with input protein sequences that are converted into numerical representations (embeddings) using the various models being evaluated [4]. These embeddings are then compressed using methods like mean pooling, which has been shown to consistently outperform other compression techniques across diverse tasks [7]. The compressed embeddings serve as input features for predictors, typically fully connected neural networks, which are trained to predict specific protein properties or functions [4]. Performance is evaluated on hold-out test sets using task-appropriate metrics and compared against traditional methods like BLASTp and baseline models using one-hot encodings [4] [11]. For protein stability prediction, the workflow involves additional steps to compute differences between wild-type and variant protein embeddings, which are then processed through convolutional neural networks to predict stability changes (ΔΔG) [12].

Domain-Adaptive Pretraining Methodology

Diagram 2: Domain-Adaptive Pretraining Process

Domain-adaptive pretraining has emerged as a powerful technique to enhance the performance of general protein language models for specialized applications. The process involves several methodical steps [10]: First, a curated dataset of domain-specific protein sequences is compiled, such as the UniDBP40 dataset containing 170,264 non-redundant DNA-binding protein sequences for ESM-DBP [10]. The general ESM-2 model then undergoes additional pretraining on this specialized dataset, but with a strategic parameter update approach where the early transformer blocks (capturing general protein knowledge) remain frozen while the later blocks (capturing specialized patterns) are updated [10]. This approach preserves the fundamental biological knowledge acquired during general pretraining while adapting the model to recognize domain-specific patterns. The resulting domain-adapted model demonstrates significantly improved feature representation for the target domain, enabling better performance on related downstream prediction tasks even for sequences with few homologous examples [10].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Key Research Tools and Resources

| Tool/Resource | Type | Function | Access |

|---|---|---|---|

| ESM-2 Models | Protein Language Model | Feature extraction, structure prediction | GitHub, HuggingFace, TorchHub |

| ProtBERT | Protein Language Model | Feature extraction, function prediction | HuggingFace |

| UniProt Database | Protein Sequence Database | Source of training and benchmark data | Public web access |

| EC Number Annotations | Functional Labels | Ground truth for enzyme function prediction | Public databases |

| Deep Mutational Scanning Data | Experimental Measurements | Validation for stability and function predictions | Public repositories |

| BLASTp | Sequence Alignment Tool | Baseline comparison method | Public web access, standalone |

| Thailanstatin B | Thailanstatin B, MF:C28H42ClNO9, MW:572.1 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Iron(3+);bromide | Iron(3+);bromide, MF:BrFe+2, MW:135.75 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

The comprehensive comparison of ESM-2 with ProtBERT and other protein language models reveals a complex landscape where model selection depends heavily on specific research goals, computational resources, and target applications. ESM-2 consistently demonstrates superior performance in structure-related predictions and challenging annotation tasks, particularly for sequences with limited homology to known proteins [4] [11] [12]. The framework's scalability, with model sizes ranging from 8 million to 15 billion parameters, makes it adaptable to diverse research environments [7] [8]. ProtBERT remains a competitive alternative, particularly in general function prediction tasks, with fusion models demonstrating that combining multiple protein language models can capture complementary features for enhanced performance [5]. Future developments in protein language modeling will likely focus on specialized adaptations for particular protein families or functions, improved efficiency for broader accessibility, and enhanced interpretability to extract biological insights from model predictions [10]. As these models continue to evolve, they will play an increasingly central role in accelerating protein research, drug discovery, and synthetic biology applications.

Protein language models (pLMs) have revolutionized computational biology by enabling deep insights into protein function, structure, and interactions directly from amino acid sequences. Among these, ProtBERT stands as a significant adaptation of the Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers (BERT) architecture specifically designed for protein sequence analysis. This guide provides an objective comparison of ProtBERT's performance against other prominent models, particularly ESM2, across various biological tasks including enzyme function prediction, drug-target interaction forecasting, and secondary structure prediction. As the field increasingly relies on these computational tools for tasks ranging from drug discovery to enzyme annotation, understanding their relative strengths, limitations, and optimal applications becomes crucial for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Model Architecture and Technical Foundations

ProtBERT adapts the original BERT architecture, which was transformative for natural language processing (NLP), to the "language" of proteins—sequences of amino acids. The model was pre-trained on massive datasets from UniRef and the BFD database, containing up to 393 billion amino acids, using the Masked Language Modeling (MLM) objective. In this approach, random amino acids in sequences are masked, and the model learns to predict them based on contextual information from surrounding residues. This self-supervised training enables ProtBERT to capture complex biochemical properties and evolutionary patterns without requiring labeled data [13] [3].

The input to ProtBERT is the raw amino acid sequence of a protein, with a maximum sequence length typically set to 545 residues to cover 95% of amino acid sequence length distribution while maintaining computational efficiency. Longer sequences are truncated to fit this constraint. The model uses character-level tokenization with a vocabulary size of 30, representing the 20 standard amino acids plus special tokens. Similar to BERT in NLP, ProtBERT employs a [CLS] token at the beginning of each sequence whose final hidden state serves as an aggregated sequence representation for classification tasks [13].

ESM2 (Evolutionary Scale Modeling 2) represents a different architectural approach based on the transformer architecture but optimized specifically for protein modeling across evolutionary scales. ESM2 models range dramatically in size from 8 million to 15 billion parameters, with the largest models capturing increasingly complex patterns in protein sequences. Unlike ProtBERT, ESM2 employs a standard transformer architecture with carefully designed pre-training objectives focused on capturing evolutionary relationships [7] [3].

Table: Architectural Comparison Between ProtBERT and ESM2

| Feature | ProtBERT | ESM2 |

|---|---|---|

| Base Architecture | BERT | Standard Transformer |

| Pre-training Objective | Masked Language Modeling | Masked Language Modeling |

| Pre-training Data | UniRef, BFD (393B amino acids) | UniProtKB |

| Maximum Sequence Length | 545 residues | Varies by model size |

| Tokenization | Character-level | Subword-level |

| Vocabulary Size | 30 | Varies |

| Parameter Range | Fixed size | 8M to 15B parameters |

Model Architecture Comparison: ProtBERT utilizes character-level tokenization and a BERT encoder stack, while ESM2 employs subword tokenization and a standard transformer encoder.

Performance Comparison Across Biological Tasks

Enzyme Commission Number Prediction

Enzyme Commission (EC) number prediction is a crucial task for annotating enzyme function in genomic studies. A comprehensive 2025 study directly compared ProtBERT against ESM2, ESM1b, and traditional methods like BLASTp for this task. The research revealed that while BLASTp provided marginally better results overall, protein LLMs complemented alignment-based methods by excelling in different scenarios [4] [11].

ESM2 emerged as the top-performing language model for EC number prediction, particularly for difficult annotation tasks and enzymes without homologs in reference databases. ProtBERT demonstrated competitive performance but fell short of ESM2's accuracy in most categories. Both LLMs significantly outperformed deep learning models relying on one-hot encodings of amino acid sequences, confirming the value of pre-trained representations [4].

Notably, the study found that LLMs like ProtBERT and ESM2 provided particularly strong predictions when sequence identity between query sequences and reference databases fell below 25%, suggesting their special utility for annotating distant homologs and poorly characterized enzyme families. This capability addresses a critical gap in traditional homology-based methods [4] [11].

Table: EC Number Prediction Performance Comparison

| Model/Method | Overall Accuracy | Performance on Difficult Cases | Performance without Homologs |

|---|---|---|---|

| BLASTp | Highest | Moderate | Poor |

| ESM2 | High | Highest | Highest |

| ProtBERT | Moderate-High | High | High |

| One-hot Encoding DL Models | Moderate | Low | Moderate |

Drug-Target Interaction Prediction

Drug-target interaction (DTI) prediction represents another critical application where ProtBERT has demonstrated notable success. In a 2022 study, researchers developed a DTI prediction model combining ChemBERTa for drug compounds with ProtBERT for target proteins. This approach achieved state-of-the-art performance with the highest reported AUC and precision-recall AUC values, outperforming previous models [13].

The model leveraged ProtBERT's contextual understanding of protein sequences to capture interaction patterns that simpler encoding methods might miss. The researchers found that integrating multiple databases (BIOSNAP, DAVIS, and BindingDB) for training further enhanced performance. A case study focusing on cytochrome P450 substrates confirmed the model's excellent predictive capability for real-world drug metabolism applications [13].

A 2023 study further validated ProtBERT's utility in DTI prediction through a graph-based approach called DTIOG that integrated knowledge graph embedding with ProtBERT pre-training. The method combined ProtBERT's sequence representations with structured knowledge from biological graphs, achieving superior performance across Enzymes, Ion Channels, and GPCRs datasets [14].

Secondary Structure Prediction

For protein secondary structure prediction (PSSP), ProtBERT has shown particular value when computational efficiency is a concern. A 2025 study demonstrated that ProtBERT-derived embeddings could be compressed using autoencoder-based dimensionality reduction from 1024 to 256 dimensions while preserving over 99% of predictive performance. This compression reduced GPU memory usage by 67% and training time by 43%, making high-quality PSSP more accessible for resource-constrained environments [15].

The research utilized a Bi-LSTM classifier on top of compressed ProtBERT embeddings, evaluating performance on both Q3 (3-class) and Q8 (8-class) secondary structure classification schemes. The optimal configuration used 256-dimensional embeddings with subsequence lengths of 50 residues, balancing contextual learning with training stability [15].

General Protein Function Prediction

In broader protein function prediction tasks, medium-sized models have demonstrated surprisingly competitive performance compared to their larger counterparts. A 2025 systematic evaluation found that while larger ESM2 models (up to 15B parameters) captured more complex patterns, medium-sized models (ESM-2 650M and ESM C 600M) performed nearly as well, especially when training data was limited [7].

The study also revealed that mean pooling (averaging embeddings across all sequence positions) consistently outperformed other embedding compression methods for transfer learning, particularly when input sequences were widely diverged. This finding has practical implications for applying ProtBERT and similar models to diverse protein families [7].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standard Evaluation Framework for Protein Language Models

To ensure fair comparison between ProtBERT and ESM2, researchers typically employ a standardized evaluation framework consisting of multiple biological tasks and datasets. The protocol generally follows these steps:

Embedding Extraction: For each model, protein sequences are converted into numerical embeddings. For ProtBERT, the [CLS] token embedding is typically used as the sequence representation, while ESM2 often employs mean-pooled residue embeddings [13] [7].

Feature Compression: High-dimensional embeddings (often 1024-4096 dimensions) are compressed using methods like mean pooling, max pooling, or PCA to make them manageable for downstream classifiers [7].

Classifier Training: Compressed embeddings serve as input to supervised machine learning models (typically fully connected neural networks or regularized regression) trained on annotated datasets [4] [7].

Evaluation: Models are evaluated on hold-out test sets using task-appropriate metrics (e.g., AUC-ROC for DTI prediction, Q3/Q8 accuracy for secondary structure) [7] [15].

Experimental Evaluation Workflow: Standardized protocol for comparing protein language models involving embedding extraction, compression, and supervised classification.

Key Benchmarking Datasets

Robust evaluation of ProtBERT and ESM2 requires diverse, high-quality benchmarking datasets:

- UniProtKB/SwissProt: Manually annotated protein sequences with EC numbers, gene ontology terms, and other functional descriptors [4].

- PISCES Dataset: Curated protein sequences with structural annotations for secondary structure prediction [7] [15].

- DTI Benchmarks: BIOSNAP, DAVIS, and BindingDB provide drug-target interaction pairs for pharmacological applications [13] [14].

- Deep Mutational Scanning (DMS): Datasets measuring functional consequences of protein variants for assessing mutational effect prediction [7].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Implementing and evaluating protein language models requires specific computational resources and datasets. The following table outlines essential "research reagents" for working with ProtBERT and comparable models.

Table: Essential Research Reagents for Protein Language Model Research

| Resource | Type | Function | Example Sources |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-trained Models | Software | Provide foundational protein representations | Hugging Face Model Hub, ESMBenchmarks |

| Protein Sequence Databases | Data | Training and evaluation data for specific tasks | UniProtKB, SwissProt, TrEMBL |

| Functional Annotations | Data | Ground truth labels for supervised tasks | Enzyme Commission, Gene Ontology |

| Structural Datasets | Data | Secondary and tertiary structure information | PISCES, Protein Data Bank |

| Interaction Databases | Data | Drug-target and protein-protein interactions | BIOSNAP, DAVIS, BindingDB |

| Embedding Compression Tools | Software | Dimensionality reduction for high-dim embeddings | Scikit-learn, Custom Autoencoders |

| Specialized Classifiers | Software | Task-specific prediction architectures | Bi-LSTM Networks, Fully Connected DNNs |

| Allyl-but-2-ynyl-amine | Allyl-but-2-ynyl-amine, MF:C7H11N, MW:109.17 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| 5-n-Boc-aminomethyluridine | 5-n-Boc-aminomethyluridine| | 5-n-Boc-aminomethyluridine is a protected nucleoside building block for oligonucleotide synthesis and RNA research. For Research Use Only. Not for human or therapeutic use. | Bench Chemicals |

ProtBERT represents a significant milestone in adapting successful NLP architectures to biological sequences, demonstrating strong performance across multiple protein analysis tasks. When compared against ESM2, the current evidence suggests a nuanced performance landscape: ESM2 generally outperforms ProtBERT for enzyme function prediction, particularly for challenging cases and sequences without close homologs. However, ProtBERT maintains competitive advantages in specific applications like drug-target interaction prediction and offers practical efficiency benefits for resource-constrained environments.

The choice between ProtBERT and ESM2 ultimately depends on the specific research context—the biological question, available computational resources, dataset characteristics, and performance requirements. Rather than a clear superiority of one model, the research reveals complementary strengths, suggesting that ensemble approaches or task-specific model selection may yield optimal results. As protein language models continue to evolve, focusing on improved training strategies, better efficiency, and specialized architectures for biological applications will likely drive the next generation of advancements in this rapidly progressing field.

The performance of Protein Language Models (PLMs) like ESM-2 and ProtBERT is fundamentally constrained by the quality, size, and composition of their training data. UniRef (UniProt Reference Clusters) and BFD (Big Fantastic Database) represent crucial protein sequence resources that serve as the foundational training corpora for these models. The strategic selection between these databases involves critical trade-offs between sequence diversity, redundancy reduction, and functional coverage that directly influence a model's ability to learn meaningful biological representations. UniRef databases provide clustered sets of sequences from the UniProt Knowledgebase at different identity thresholds, with UniRef100 representing complete sequences without redundancy, UniRef90 clustering at 90% identity, and UniRef50 providing broader diversity at 50% identity [16]. In contrast, BFD incorporates substantial metagenomic data alongside UniProt sequences, offering approximately 10x more protein sequences than standard UniRef databases [17]. Understanding the architectural and compositional differences between these datasets is essential for researchers leveraging PLMs in scientific discovery and drug development applications, as these differences manifest directly in downstream task performance across structure prediction, function annotation, and engineering applications.

Database Architectures and Technical Specifications

UniRef Database Family

The UniRef databases employ a hierarchical clustering approach to provide non-redundant coverage of protein sequence space at multiple resolutions. UniRef100 forms the foundation by combining identical sequences and subfragments from any source organism into single clusters, effectively removing 100% redundancy. UniRef90 and UniRef50 are built through subsequent clustering of UniRef100 sequences at 90% and 50% sequence identity thresholds, respectively [16]. A critical enhancement implemented in January 2013 introduced an 80% sequence length overlap threshold for UniRef90 and UniRef50 calculations, preventing proteins sharing only partial sequences (such as polyproteins and their components) from being clustered together, thereby significantly improving intra-cluster molecular function consistency [16].

Table 1: UniRef Database Technical Specifications

| Database | Sequence Identity Threshold | Length Overlap Threshold | Key Characteristics | Primary Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| UniRef100 | 100% | None | Combines identical sequences and subfragments; no sequence redundancy | Baseline clustering; subfragment analysis |

| UniRef90 | 90% | 80% | Balance between redundancy reduction and sequence preservation; improved functional consistency | Default for many tools (e.g., ShortBRED); general-purpose modeling |

| UniRef50 | 50% | 80% | Broad sequence diversity; maximizes functional coverage while reducing database size | Remote homology detection; evolutionary analysis |

| BFD | Mixed | Varies | Combines UniRef with Metaclust and other metagenomic data; ~10x more sequences than UniRef | Large-scale training; metagenomic applications |

BFD Database Composition

The BFD represents a composite database that extends beyond UniRef's scope by incorporating extensive metagenomic sequences from sources like Metaclust and Soil Reference Catalog Marine Eukaryotic Reference Catalog assembled by Plass [17]. This inclusion provides dramatically expanded sequence diversity, particularly from uncultured environmental microorganisms, offering a more comprehensive snapshot of the natural protein universe. The database's hybrid nature results in substantial but not complete overlap with UniRef sequences while adding considerable novel sequence content from metagenomic sources [17].

Database Utilization in Protein Language Models

Training Data Selection for Major PLMs

The architectural differences between databases have led to distinct adoption patterns among major protein language models. The ESM family models, including ESM-1b and ESM-2, were predominantly trained on UniRef50, leveraging its balance of diversity and reduced redundancy for effective learning of evolutionary patterns [5] [18]. The ProtBERT model utilized UniRef100 or the larger BFD database for training, benefiting from more extensive sequence coverage despite higher redundancy [5] [19]. This fundamental divergence in training data strategy reflects differing philosophies in model optimization—ESM prioritizes clean, diverse evolutionary signals while ProtBERT leverages maximal sequence information.

Performance Implications of Database Selection

Research indicates that clustering strategies significantly impact model performance across different task types. For masked language models (MLMs) like ProtBERT, training on clustered datasets (UniRef50/90) typically yields superior results, whereas autoregressive models may perform better with less clustering (UniRef100) [17]. The ESM-1v authors systematically evaluated clustering thresholds and identified the 50-90% identity range as optimal for zero-shot fitness prediction, with models trained at higher or lower thresholds demonstrating reduced performance [17]. This relationship between clustering intensity and model performance appears non-linear, with the 90% clustering threshold often delivering the highest average performance on downstream tasks [17].

Table 2: Database Usage in Major Protein Language Models

| Model | Primary Training Database | Model Architecture | Notable Performance Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| ESM-2 | UniRef50 [5] [18] | Transformer (Encoder-only) | State-of-the-art structure prediction; strong on remote homology detection |

| ESM-1b | UniRef50 [5] | Transformer (Encoder-only) | Excellent results on structure/function tasks; baseline for ESM family |

| ESM-1v | UniRef90 [5] | Transformer (Encoder-only) | Optimized for variant effect prediction without additional training |

| ProtBERT | UniRef100 or BFD [5] [19] | Transformer (Encoder-only) | Strong semantic representations; benefits from larger database size |

| ProtT5 | BFD-100 + UniRef50 [18] | Transformer (Encoder-Decoder) | High-performance embeddings; trained on 7 billion proteins |

Experimental Evidence: Database Impact on Model Performance

Sequence Similarity Search Sensitivity

Comparative studies demonstrate that database selection directly impacts computational efficiency and sensitivity in sequence analysis. When using BLASTP searches against UniRef50 followed by cluster member expansion, researchers observed ~7 times shorter hit lists and ~6 times faster execution while maintaining >96% recall at e-value <0.0001 compared to searches against full UniProtKB [16]. This demonstrates that the redundancy reduction in UniRef50 preserves sensitivity while dramatically improving computational efficiency—a critical consideration for large-scale proteomic analyses.

Embedding-Based Alignment Accuracy

The PEbA (Protein Embedding Based Alignment) study directly compared embeddings from ProtT5 (trained on BFD+UniRef50) and ESM-2 (trained on UniRef50) for twilight zone alignment of sequences with <20% pairwise identity [18]. Results demonstrated that ProtT5-XL-U50 embeddings produced substantially more accurate alignments than ESM-2, achieving over four times improvement for sequences with <10% identity compared to BLOSUM matrix-based methods [18]. This performance advantage likely stems from ProtT5's training on the larger combined BFD and UniRef50 dataset, enabling better capture of remote homology signals.

Function Prediction and Structural Annotation

Large-scale analysis of the natural protein universe reveals that UniRef50 clusters approximately 350 million unique UniProt sequences down to about 50 million non-redundant representatives [20]. Within this space, approximately 34% of UniRef50 clusters remain functionally "dark" with less than 5% functional annotation coverage [20]. The expansion of database coverage through metagenomic integration in BFD directly addresses this limitation by providing contextual sequences that enable better functional inference for previously uncharacterized protein families.

Table 3: Critical Databases and Tools for Protein Language Model Research

| Resource | Type | Function in Research | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| UniRef50 | Sequence Database | Provides diverse, non-redundant protein sequences clustered at 50% identity | Training ESM models; remote homology detection; evolutionary studies [16] [18] |

| UniRef90 | Sequence Database | Balance between diversity and resolution; clusters at 90% identity with 80% length overlap | ShortBRED marker building; general-purpose sequence analysis [21] |

| UniRef100 | Sequence Database | Comprehensive non-fragment sequences without identity clustering | Training ProtBERT; full sequence space analysis [16] [5] |

| BFD | Sequence Database | Extensive metagenomic-integrated database with ~10x more sequences than UniRef | Large-scale training; metagenomic protein discovery [17] [19] |

| ESM-2 | Protein Language Model | Transformer model trained on UniRef50; produces structure-aware embeddings | State-of-the-art structure prediction; embedding-based alignment [5] [18] |

| ProtBERT | Protein Language Model | BERT-based model trained on UniRef100/BFD; generates semantic protein representations | Function prediction; sequence classification [5] [19] |

| PEbA | Alignment Tool | Embedding-based alignment using ProtT5 or ESM-2 embeddings for twilight zone sequences | Aligning sequences with <20% identity; remote homology detection [18] |

| AlphaFold DB | Structure Database | Predicted structures for UniProt sequences; provides structural ground truth | Model evaluation; structure-function relationship studies [20] |

The comparative analysis reveals that database selection between UniRef50, UniRef100, and BFD represents a strategic decision with measurable impacts on protein language model performance. UniRef50 provides optimal balance for most research applications, offering sufficient diversity while managing computational complexity—making it ideal for training foundational models like ESM-2. UniRef100 retains maximal sequence information at the cost of redundancy, serving well for models like ProtBERT that benefit from comprehensive sequence coverage. BFD extends beyond traditional sequencing sources with massive metagenomic integration, offering unparalleled diversity for discovering novel protein families and functions. For researchers targeting specific applications, the experimental evidence suggests clustering thresholds between 50-90% generally optimize performance, with the exact optimum depending on model architecture and task requirements. As the protein universe continues to expand through metagenomic sequencing, the integration of diverse database sources will become increasingly critical for developing models that comprehensively capture nature's structural and functional diversity.

The prediction of protein function from sequence alone is a fundamental challenge in bioinformatics and drug discovery. A critical first step in most modern computational approaches is the conversion of variable-length amino acid sequences into fixed-length numerical representations, or embeddings. These embeddings serve as input for downstream tasks such as enzyme function prediction, subcellular localization, and fitness prediction. Among the most advanced tools for this purpose are protein Language Models (pLMs), such as the Evolutionary Scale Modeling 2 (ESM2) and ProtBERT families of models. These models, pre-trained on millions of protein sequences, learn deep contextual representations of protein sequence "language." This guide provides an objective comparison of ESM2 and ProtBERT for generating fixed-length embeddings, synthesizing performance data from recent benchmarks to aid researchers in selecting the optimal model for their specific application.

Performance Comparison Tables

The following tables summarize quantitative performance data for ESM2 and ProtBERT across a range of canonical protein prediction tasks. The data, sourced from the FLIP benchmark suite as reproduced in NVIDIA's BioNeMo Framework documentation, allows for a direct comparison of the models' capabilities when used as feature extractors [22].

Table 1: Performance on Protein Classification Tasks

| Model | Secondary Structure (Accuracy) | Subcellular Localization (Accuracy) | Conservation (Accuracy) |

|---|---|---|---|

| One Hot Encoding | 0.643 | 0.386 | 0.202 |

| ProtBERT | 0.818 | 0.740 | 0.326 |

| ESM2 T33 650M UR50D | 0.855 | 0.791 | 0.329 |

| ESM2 T36 3B UR50D | 0.861 | 0.812 | 0.337 |

| ESM2 T48 15B UR50D | 0.867 | 0.839 | 0.340 |

Table 2: Performance on Protein Regression Tasks

| Model | Meltome (MSE) | GB1 Binding Activity (MSE) |

|---|---|---|

| One Hot Encoding | 128.21 | 2.56 |

| ProtBERT | 58.87 | 1.61 |

| ESM2 T33 650M UR50D | 53.38 | 1.67 |

| ESM2 T36 3B UR50D | 45.78 | 1.64 |

| ESM2 T48 15B UR50D | 39.49 | 1.52 |

Key Performance Insights:

- ESM2 Superiority: Across nearly all tasks and model sizes, ESM2 variants demonstrate superior performance compared to ProtBERT. For instance, in secondary structure prediction, the largest ESM2 model (15B parameters) achieves an accuracy of 0.867, compared to ProtBERT's 0.818 [22].

- Scaling Benefits: Within the ESM2 family, a clear trend emerges where larger models (from 650M to 15B parameters) consistently deliver improved performance on classification and regression tasks, such as a reduction in Mean Squared Error (MSE) on the Meltome dataset [22].

- Task-Dependent Strengths: The performance gap can vary. In conservation prediction, ESM2 and ProtBERT show more comparable results, whereas for subcellular localization, ESM2 models show a more substantial lead [22].

Experimental Protocols for Benchmarking

The comparative data presented in the previous section is derived from standardized evaluation protocols. Understanding these methodologies is crucial for interpreting the results and designing independent experiments.

Benchmarking Workflow

The general workflow for benchmarking embedding models involves data preparation, feature extraction, model training, and evaluation on held-out test sets.

Detailed Methodologies

Data Sourcing and Curation:

- Datasets: Benchmarks rely on publicly available, curated datasets. Examples include:

- Secondary Structure & Conservation: Data derived from structural databases like the Protein Data Bank (PDB), with labels assigned per amino acid [22].

- Subcellular Localization: The DeepLoc 1.0 dataset, which contains protein sequences annotated with their cellular compartment [22].

- Meltome: A dataset measuring protein thermal stability [22].

- Enzyme Commission (EC) Number Prediction: Data extracted from UniProtKB (SwissProt and TrEMBL), using only UniRef90 cluster representatives to reduce sequence redundancy and overestimation of performance [4].

- Data Splitting: To ensure realistic performance estimates, sequences are split into training and test sets using "mixed" or "homology-aware" splits. This involves clustering sequences by identity (e.g., 80% threshold) and placing entire clusters into either the training or test set, preventing models from scoring well simply by recognizing highly similar sequences seen during training [4] [22].

- Datasets: Benchmarks rely on publicly available, curated datasets. Examples include:

Embedding Generation and Compression:

- Feature Extraction: The pLM (ESM2 or ProtBERT) acts as a feature extractor without fine-tuning. The protein sequence is input, and the model's internal representations are extracted.

- Compression to Fixed Length: Per-residue embeddings are compressed into a single, fixed-length vector per protein for tasks like subcellular localization. Mean pooling (averaging embeddings across all sequence positions) has been systematically demonstrated to be a highly effective and often superior compression method compared to alternatives like max pooling or PCA [7]. This method provides a robust summary of the global protein properties.

Downstream Training and Evaluation:

- The fixed-length embeddings are used as features to train a simple downstream predictor, typically a fully connected neural network or a linear model [4] [7].

- The trained predictor is evaluated on the held-out test set using task-appropriate metrics:

- Accuracy for classification tasks (e.g., secondary structure, localization).

- Mean Squared Error (MSE) for regression tasks (e.g., thermostability, binding activity).

- Spearman's Rank Correlation for fitness prediction benchmarks like ProteinGym [23].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Item Name | Function / Application | Relevant Context |

|---|---|---|

| UniProt Knowledgebase (UniProtKB) | Primary source of protein sequence and functional annotation data. | Used for pre-training pLMs and as a source for curating downstream task datasets [4] [3]. |

| Protein Data Bank (PDB) | Repository for experimentally determined 3D protein structures. | Source of data for tasks like secondary structure prediction and residue-level conservation [22]. |

| ESM2 Model Suite | Family of pLMs of varying sizes (8M to 15B parameters) for generating protein sequence embeddings. | General-purpose model for feature extraction; larger models show superior performance but require more resources [7] [22]. |

| ProtBERT Model | BERT-based pLM pre-trained on UniRef100 and BFD databases. | Strong baseline model for comparison; often outperformed by ESM2 in recent benchmarks [4] [22]. |

| Mean Pooling | Standard operation to compress per-residue embeddings into a single, fixed-length vector. | Crucial post-processing step for protein-level prediction tasks; proven to be highly effective [7]. |

| Tyrosine Kinase Peptide 1 | Tyrosine Kinase Peptide 1, MF:C77H124N18O23, MW:1669.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 2-Chloro-2'-deoxyinosine | 2-Chloro-2'-deoxyinosine|RUO | 2-Chloro-2'-deoxyinosine (CAS 136834-39-4) is a purine nucleoside derivative for nucleic acid structure research. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

Practical Implementation and Broader Context

Generating Fixed-Length Embeddings

The process for generating a fixed-length embedding for a protein sequence is standardized across models. The following diagram and steps outline the core technical procedure.

- Input and Tokenization: The raw amino acid sequence (e.g., in FASTA format) is tokenized into a sequence of discrete tokens corresponding to the 20 standard amino acids, plus special tokens for unknown residues ("X") and sequence start/end.

- Model Forward Pass: The tokenized sequence is fed into the pre-trained pLM (ESM2 or ProtBERT). The model processes the sequence through its multiple transformer layers, applying self-attention mechanisms to capture contextual relationships between all amino acids.

- Embedding Extraction: The output from the final hidden layer (or a specific layer) of the model is extracted, resulting in a high-dimensional embedding vector for each amino acid position in the sequence.

- Compression via Mean Pooling: To obtain a single, fixed-dimensional vector representing the entire protein, the per-residue embeddings are aggregated using mean pooling. This operation calculates the element-wise average across the sequence dimension, effectively summarizing the global sequence information into a robust, fixed-length representation.

Critical Considerations for Model Selection

Beyond raw benchmark numbers, several factors are critical for selecting the right model:

- The Scaling Wall and Efficiency: While larger ESM2 models perform better, the performance gains follow a law of diminishing returns. Evidence from ProteinGym benchmarks indicates that scaling pLMs beyond 1-4 billion parameters yields minimal to no improvement—and sometimes even degradation—in zero-shot fitness prediction [23]. Furthermore, larger models are computationally expensive for inference and fine-tuning. Medium-sized models (e.g., ESM2 650M) often provide an optimal balance of performance and computational cost, making them a practical choice for most research applications [7].

- Complementarity with Traditional Methods: pLMs are not always superior to traditional homology-based methods like BLASTp. One comprehensive study found that while BLASTp provided marginally better overall results for Enzyme Commission (EC) number prediction, ESM2-based models excelled at predicting functions for enzymes with no close homologs (sequence identity <25%) [4]. This suggests that pLMs and homology-based methods are complementary and can be effectively used in tandem.

- The Power of Fusion: For maximum predictive power on specific tasks, fusing embeddings from multiple pLMs can be highly effective. For example, the FusPB-ESM2 model, which combines features from both ProtBERT and ESM-2, achieved state-of-the-art performance in predicting cell-penetrating peptides, demonstrating that the two models can capture complementary information [24] [5].

The accurate prediction of protein function is a cornerstone of modern biology, with implications for enzyme characterization and the design of therapeutic peptides. Protein Language Models (pLMs), trained on vast datasets of protein sequences, have emerged as powerful tools for this task. They learn evolutionary and biochemical patterns, allowing them to predict function from sequence alone. This guide objectively compares the performance of two leading pLMs—ESM-2 and ProtBERT—focusing on two critical applications: the annotation of Enzyme Commission (EC) numbers and the prediction of Cell-Penetrating Peptides (CPPs). We present experimental data, detailed methodologies, and performance metrics to assist researchers in selecting the appropriate model for their specific research needs in drug development and bioinformatics.

Model Performance Comparison

Performance on Enzyme Commission (EC) Number Prediction

EC numbers provide a hierarchical classification for enzymes based on the chemical reactions they catalyze [25]. The first digit represents one of seven main classes (e.g., oxidoreductases, transferases), with subsequent digits specifying the reaction with increasing precision [26]. Accurate EC number prediction is essential for functional genomics and metabolic engineering.

A comprehensive study directly compared ESM2, ESM1b, and ProtBERT for EC number prediction against the standard tool BLASTp [4]. The findings revealed that although BLASTp provided marginally better results overall, the deep learning models provided complementary results. ESM2 stood out as the best model among the pLMs tested, particularly for more difficult annotation tasks and for enzymes without close homologs in databases [4].

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Models for EC Number Prediction

| Model / Method | Core Principle | Key Performance Insight | Relative Strength |

|---|---|---|---|

| BLASTp | Sequence alignment and homology search [4] | Marginally better overall performance [4] | Gold standard for sequences with clear homologs [4] |

| ESM2 | Protein language model (Transformer-based) [4] | Most accurate pLM; excels on difficult annotations and sequences with low homology (<25% identity) [4] | Best-in-class pLM for EC prediction, robust for non-homologous enzymes |

| ProtBERT | Protein language model (BERT-based) [4] | Provides good predictions, but outperformed by ESM2 in comparative assessment [4] | A capable pLM, though not the top performer for this specific task |

| Ensemble (ESM2 + BLASTp) | Combination of pLM and homology search | Performance surpasses that achieved by individual techniques [4] | Most effective overall strategy, leveraging strengths of both approaches |

Performance on Cell-Penetrating Peptide (CPP) Prediction

CPPs are short peptides (typically 5-30 amino acids) that can cross cell membranes and facilitate the intracellular delivery of various cargoes, from small molecules to large proteins and nucleic acids [27] [28]. They are broadly classified as cationic, amphipathic, or hydrophobic based on their physicochemical properties [29].

The FusPB-ESM2 model, a fusion of ProtBERT and ESM-2, was developed to address the need for accurate computational prediction of CPPs [5]. In experiments on public datasets, this fusion model demonstrated state-of-the-art performance, surpassing conventional computational methods like CPPpred, CellPPD, and CPPDeep in prediction accuracy and reliability [5].

Table 2: Performance of FusPB-ESM2 vs. Other Computational Methods for CPP Prediction

| Model / Method | Core Principle | Key Performance Insight | Reported Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| CPPPred | Feedforward Neural Networks (FNN) [5] | Baseline performance | Outperformed by FusPB-ESM2 [5] |

| SVM-based Methods | Support Vector Machine [5] | Baseline performance | Outperformed by FusPB-ESM2 [5] |

| CellPPD | Feature extraction with Random Forests/SVM [5] | Baseline performance | Outperformed by FusPB-ESM2 [5] |

| CPPDeep | Character embedding with CNN and LSTM [5] | Baseline performance | Outperformed by FusPB-ESM2 [5] |

| FusPB-ESM2 | Fusion of features from ProtBERT and ESM-2 [5] | State-of-the-art accuracy and reliability [5] | Best performing model, leveraging complementary features from both pLMs |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol for EC Number Prediction Benchmarking

The comparative assessment of ESM2, ProtBERT, and other models for EC number prediction followed a rigorous experimental pipeline [4]:

- Data Curation: Protein sequences and their EC numbers were extracted from the UniProt Knowledgebase (UniProtKB). To avoid bias from sequence redundancy, only representative sequences from UniRef90 clusters were kept [4].

- Problem Formulation: EC number prediction was treated as a multi-label classification problem, accounting for promiscuous and multi-functional enzymes. The entire EC number hierarchy was included in the label matrix [4].

- Feature Extraction: For the pLMs (ESM2, ESM1b, ProtBERT), embeddings were extracted from the models' hidden layers. These embeddings served as numerical feature representations of the input protein sequences [4].

- Model Training & Evaluation: The extracted features were used to train fully connected neural networks. The performance of these deep learning models was compared against each other and against the baseline BLASTp tool [4].

Protocol for CPP Prediction with FusPB-ESM2

The development and validation of the FusPB-ESM2 model involved the following key steps [5]:

- Dataset Construction: A publicly available benchmark dataset was used. Positive samples were CPPs confirmed by physical experiments from the CPPsite2.0 database. Negative samples were peptides not labeled as cell-penetrating from the SATPdb database [5].

- Feature Extraction and Fusion:

- Dual-Model Feature Extraction: The protein sequences were input into both the ProtBERT and ESM-2 models. The last hidden layer outputs of both models were extracted as feature representations.

- Feature Fusion: The feature vectors from ProtBERT and ESM-2 were concatenated (fused) to create a comprehensive feature set that captures the strengths of both models [5].

- Model Architecture and Training: The fused feature vector was passed to a final classification layer (an N-to-2 linear mapping) to predict whether a peptide is a CPP or not. The model was trained and its hyperparameters were tuned using the public dataset [5].

- Performance Validation: The model was evaluated on independent test data using standard metrics such as the Area Under the Curve (AUC) of the Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve to confirm its state-of-the-art performance [5].

Table 3: Essential Resources for pLM-based Protein Function Prediction

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| UniProtKB | Database | Source of expertly annotated and computationally analyzed protein sequences and functional information, including EC numbers [4]. |

| CPPsite 2.0 | Database | Repository of experimentally validated Cell-Penetrating Peptides, used as a source of positive training and testing data [5]. |

| SATPdb | Database | A database of therapeutic peptides, useful for sourcing negative (non-penetrating) peptide sequences for model training [5]. |

| ESM-2 | Software / Model | A state-of-the-art protein language model based on the Transformer architecture, used for generating informative protein sequence embeddings [5]. |