Error-Prone PCR and Site Saturation Mutagenesis: A Comprehensive Guide for Directed Evolution in Protein Engineering

This article provides a comprehensive overview of two cornerstone techniques in directed evolution: error-prone PCR and site saturation mutagenesis.

Error-Prone PCR and Site Saturation Mutagenesis: A Comprehensive Guide for Directed Evolution in Protein Engineering

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of two cornerstone techniques in directed evolution: error-prone PCR and site saturation mutagenesis. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational principles of creating genetic diversity, details robust methodological protocols for library construction, and offers practical troubleshooting advice. It further delivers a critical comparative analysis of these and related methods, such as Sequence Saturation Mutagenesis (SeSaM), to guide the selection of optimal strategies for specific protein engineering goals, from enzyme optimization to biosensor development.

Building Blocks of Diversity: Core Principles of Random and Targeted Mutagenesis

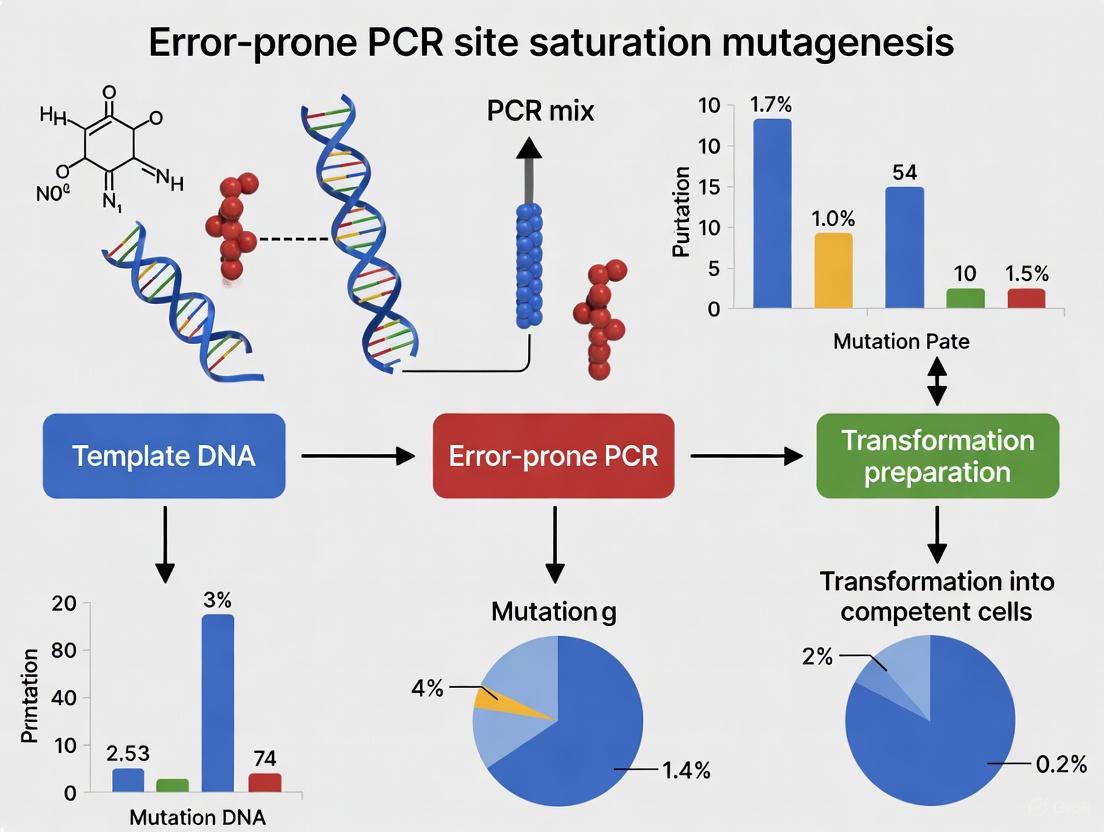

Error-prone PCR (epPCR) is a powerful directed evolution technique used to generate diverse genetic variants from a single gene template by introducing random mutations during PCR amplification [1]. By leveraging low-fidelity DNA polymerase under controlled conditions that reduce replication fidelity, researchers can create comprehensive mutant libraries for protein engineering, enzyme optimization, and functional genomics studies. This method represents a fundamental approach in the broader context of saturation mutagenesis research, enabling the exploration of sequence-function relationships without requiring prior structural knowledge.

The technique was originally developed by Leung et al. and has since become a workhorse method for combinatorial protein engineering [1]. Unlike site-saturation mutagenesis that targets specific residues, epPCR explores a wider mutational landscape, making it particularly valuable for optimizing enzyme properties such as thermostability, substrate specificity, and enantioselectivity when structural information is limited or when synergistic mutations across multiple residues are sought.

Principles and Mechanisms

Error-prone PCR introduces random mutations during DNA amplification through controlled manipulation of PCR conditions to reduce replication fidelity. The primary sources of variation stem from both polymerase misincorporation and DNA thermal damage [2].

Polymerase Errors occur when DNA polymerases incorporate incorrect nucleotides during strand elongation. The fidelity of DNA polymerases varies substantially between enzymes, with error rates ranging from approximately 1.1 errors per 10^6 base pairs for high-fidelity enzymes like KOD polymerase to significantly higher rates for non-proofreading enzymes [2]. These misincorporations are influenced by several factors:

- dNTP pool imbalances: Skewed deoxynucleotide triphosphate ratios increase misincorporation likelihood

- Magnesium concentration: Elevated Mg²⺠levels can reduce polymerase fidelity

- Template sequence context: Certain sequences are more prone to replication errors

- Extension times: Suboptimal extension parameters can promote misincorporation

Thermal Damage Errors represent a significant contributor to overall mutation rates, with three primary mechanisms:

- Depurination: Removal of purine bases (adenine or guanine) from the DNA backbone, with single-stranded DNA being particularly susceptible [2]

- Cytosine deamination: Conversion of cytosine to uracil, especially problematic at elevated temperatures [2]

- Oxidative damage: Oxidation of guanine to 8-oxoguanine, which can be mitigated by purging reactions with argon to reduce dissolved oxygen [2]

Thermal damage becomes increasingly significant with prolonged exposure to high temperatures, potentially reaching levels of 0.2-0.3% after one hour at 72°C (approximately 1 damaged base per 300-500 bases) [2].

Error Rate Quantification and Measurement

Advanced methods for quantifying epPCR error rates combine unique molecular identifier (UMI) tagging with high-throughput sequencing, enabling exceptional resolution in error detection [3]. This approach allows researchers to distinguish errors introduced during initial PCR from those occurring in subsequent amplification and sequencing steps, providing accurate per-cycle error rate measurements.

Table 1: Polymerase Error Rates and Preferences

| Polymerase | Error Rate (Substitutions/bp/cycle) | Dominant Substitution Types | Proofreading Activity |

|---|---|---|---|

| KOD Hot Start | ~1.1×10â»â¶ [2] | Not specified | Yes (3'→5' exonuclease) |

| Taq | ~1×10â»â´ [3] | A>G, T>C (20 cycles) | No |

| Phusion | ~4.6×10â»â· [3] | Not specified | Yes |

| Kapa HF | ~8.1×10â»â· [3] | C>T, G>A (20 cycles) | Yes |

| Tersus | ~1.3×10â»â¶ [3] | C>T, G>A (20 cycles) | Yes |

Different polymerases exhibit distinct substitution preferences, falling into two main categories: those predominantly generating C>T and G>A transitions, and those favoring A>G and T>C transitions [3]. This polymerase "fingerprint" significantly influences the resulting mutational spectrum and should be considered when designing epPCR experiments for specific applications.

Experimental Protocols

Standard Error-Prone PCR Protocol

Materials Required:

- Template DNA (high-purity plasmid prep, 0.1-1.0 ng/μL) [4]

- Mutagenic primers (if combining with targeted approaches)

- Low-fidelity DNA polymerase (e.g., GeneMorph II Random Mutagenesis Kit) [1]

- Modified nucleotide buffer (imbalanced dNTPs, elevated Mg²âº, Mn²âº)

- Standard PCR reagents and equipment

Procedure:

- Reaction Setup: Prepare 50μL reactions containing template DNA, 1× mutagenic buffer, 0.2mM each dNTP (or imbalanced ratios), 2-5mM MgCl₂, 0.3μM primers, and 1-2U/μL DNA polymerase [1].

Thermal Cycling:

- Initial denaturation: 94°C for 2 minutes

- 25-30 cycles of:

- Denaturation: 94°C for 15-30 seconds

- Annealing: 50-68°C for 30 seconds (optimize based on primer Tm)

- Extension: 72°C for 1-2 minutes/kb

- Final extension: 72°C for 5-10 minutes [1]

Product Analysis: Verify amplification by 1% agarose gel electrophoresis and purify using standard PCR purification kits.

Critical Parameters for Mutation Rate Control:

- Mg²⺠concentration: Increasing from 1.5mM to 5-7mM enhances error rates

- dNTP imbalances: Unequal dNTP concentrations (e.g., elevating dATP/dTTP while reducing dCTP/dGTP)

- Manganese addition: 0.1-0.5mM MnClâ‚‚ significantly increases misincorporation

- Template concentration: Higher template amounts reduce the number of replication cycles and resultant mutations

- Cycle number: Increasing cycles amplifies mutation accumulation

Improved Two-Stage PCR for Difficult Templates

For problematic templates such as plasmids containing P450-BM3 or Pseudomonas aeruginosa lipase A genes, an improved two-stage PCR method enhances success rates [5].

Workflow:

- First Stage (Megaprimer Generation): 5-10 cycles with both mutagenic primer and antiprimer (a non-mutagenic primer aiding DNA unwinding) at standard annealing temperatures

- Second Stage (Plasmid Amplification): 20 cycles with increased annealing temperature to eliminate oligonucleotide priming, allowing the megaprimer to drive amplification [5]

This approach is particularly valuable for saturation mutagenesis at single or multiple residues regardless of their location in the gene sequence and intrinsically avoids problems from palindromes, hairpins, or primer self-pairing [5].

Diagram 1: Two-stage PCR workflow

Library Construction Methods

Traditional Ligation-Dependent Cloning (LDCP):

- Primers incorporate restriction enzyme sites compatible with target plasmids

- PCR products and vectors are digested with appropriate restriction enzymes

- Ligation with DNA ligase recircularizes vectors [1]

- Limitations include significant loss of potential mutants, reducing library diversity

Circular Polymerase Extension Cloning (CPEC):

- A restriction enzyme- and ligase-free method offering superior efficiency

- High-fidelity DNA polymerase extends overlapping regions between insert and vector

- Single reaction forms circular molecules ready for transformation [1]

- Advantages: accelerated cloning, higher variant recovery, simplified procedure

Table 2: Cloning Method Comparison for Library Construction

| Parameter | LDCP (Traditional) | CPEC (Improved) |

|---|---|---|

| Efficiency | Limited efficacy, significant mutant loss | Higher variant recovery |

| Steps | Multiple: digestion, purification, ligation | Single PCR reaction |

| Time Requirement | Longer (overnight ligation possible) | Rapid (few hours) |

| Enzyme Dependence | Requires specific restriction enzymes | No restriction enzymes needed |

| Cost | Higher (multiple enzymes required) | Lower (fewer reagents) |

| Library Diversity | Reduced due to cloning bottlenecks | Better preservation of diversity |

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Error-Prone PCR

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function & Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Polymerases | GeneMorph II Kit, Taq, Mutazyme II | Low-fidelity enzymes for random mutagenesis; choice depends on desired error rate and mutational spectrum |

| Cloning Kits | NEB Q5 SDM Kit, CPEC method | Introduction of mutations into plasmids; CPEC offers advantages in efficiency and simplicity [1] [6] |

| Template Preparation | dam+ E. coli strains (e.g., DH5α) | Methylation-competent strains for subsequent DpnI digestion to remove template [4] |

| Error-Rate Modification | MnCl₂, unbalanced dNTPs, elevated Mg²⺠| Chemical mutagens to alter and control mutation frequency |

| Screening Tools | Restriction analysis, sequencing, functional assays | Identification and validation of desired mutants; high-throughput methods preferred for library screening |

Applications in Directed Evolution

Error-prone PCR serves as a foundational technology in directed evolution pipelines, enabling the improvement of enzyme properties through iterative rounds of mutation and selection. Key applications include:

- Thermostability enhancement through the B-FIT method targeting flexible regions

- Substrate scope expansion and enantioselectivity optimization via CASTing focusing on active site residues

- Organic solvent tolerance improvement for industrial biocatalysis

- pH profile modulation for applications under non-physiological conditions

The integration of epPCR with high-throughput screening methods creates a powerful platform for protein engineering, allowing researchers to explore vast sequence spaces and identify variants with desired properties that would be difficult to predict rationally.

Troubleshooting and Optimization

Common Challenges and Solutions:

- Low Mutation Frequency: Increase Mg²⺠concentration (5-7mM), add MnCl₂ (0.1-0.5mM), implement dNTP imbalances, or increase cycle number

- Poor Amplification: Optimize template quality and concentration, add DMSO (3-5%) for GC-rich templates, adjust annealing temperatures, or utilize the two-stage PCR protocol for difficult templates [5] [4]

- Limited Library Diversity: Implement CPEC cloning instead of traditional restriction-based methods, use higher template diversity, or combine with other mutagenesis methods [1]

- Template Carryover: Ensure complete DpnI digestion of methylated template DNA (from dam+ E. coli strains) [4]

Quantitative Error Monitoring: Employ high-throughput sequencing with unique molecular identifiers (UMIs) to accurately quantify error rates and profiles, enabling precise control over library quality and diversity [3].

Error-prone PCR remains an essential tool in the molecular biologist's toolkit, providing a robust method for generating diversity in directed evolution experiments. Through careful optimization of reaction conditions and integration with efficient cloning methodologies, researchers can create high-quality mutant libraries for advancing protein engineering and drug development initiatives.

The Rationale Behind Site Saturation Mutagenesis for Targeted Exploration

In the field of protein engineering and functional genomics, site saturation mutagenesis (SSM) stands as a powerful targeted approach that contrasts with non-targeted random mutagenesis methods. While error-prone PCR (epPCR) introduces mutations randomly throughout a gene, SSM provides a systematic methodology for investigating the function of specific amino acid positions by replacing them with all possible amino acid substitutions [7]. This application note delineates the rationale, advantages, and methodological frameworks for SSM, contextualized within broader directed evolution and functional analysis research, to guide researchers and drug development professionals in leveraging this technique for precise protein optimization and variant characterization.

SSM represents a sophisticated approach to systematic genetic exploration, transforming protein modification from educated guesswork into a comprehensive investigation of sequence-function relationships [7]. By methodically substituting every possible amino acid at specific positions, researchers can create "smarter libraries" that focus screening efforts on regions of interest, thereby significantly enhancing the efficiency of directed evolution campaigns [8]. This targeted strategy has proven instrumental in addressing diverse protein engineering challenges, from altering enzyme cofactor specificity to enhancing thermal stability.

SSM vs. Random Mutagenesis: A Comparative Rationale

Strategic Advantages of Targeted Exploration

The selection between SSM and random mutagenesis represents a fundamental strategic decision in protein engineering. While epPCR employs mutagenic buffers with elevated MgClâ‚‚ (7 mM), MnClâ‚‚, or unbalanced dNTP concentrations to introduce random mutations throughout a gene [9], SSM focuses investigative resources on predefined positions of interest. This focused approach offers several distinct advantages for hypothesis-driven protein engineering.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Site Saturation Mutagenesis vs. Random Mutagenesis

| Feature | Site Saturation Mutagenesis | Random Mutagenesis (epPCR) |

|---|---|---|

| Mutation Control | Targeted to specific residues | Random distribution across gene |

| Library Quality | Focused, "smarter" libraries [8] | Unbiased but with redundant coverage |

| Information Yield | Direct residue-function relationships | Global sequence-function landscape |

| Screening Efficiency | Higher hit rate per variant screened | Lower hit rate, requires high throughput [9] |

| Primary Applications | Protein engineering, critical residue identification, mechanism study [7] | Directed evolution when target regions unknown [10] |

| Technical Implementation | Two-stage PCR with mutagenic primers [5] | Modified PCR conditions with mutagenic agents [9] |

The precision of SSM enables researchers to address specific protein engineering challenges that are difficult to tackle with random approaches. For instance, SSM has been successfully employed to alter the coenzyme specificity of Candida methylica formate dehydrogenase (cmFDH) from NAD⺠to NADP⺠and to increase its thermostability by targeting specific positions in both the coenzyme binding and catalytic domains [8]. Similarly, large-scale SSM studies encompassing hundreds of human protein domains have systematically quantified the effects of over 500,000 missense variants, revealing that approximately 60% of pathogenic missense variants reduce protein stability [11].

Complementary Roles in Directed Evolution

Rather than mutually exclusive approaches, SSM and epPCR often play complementary roles in comprehensive protein engineering pipelines. epPCR serves as an exploratory tool when structural information is limited or when the target property involves distributed sequence determinants, while SSM enables focused optimization once key regions have been identified. The integration of both methods in successive rounds of directed evolution can accelerate the optimization process, with epPCR discovering beneficial regions and SSM intensively exploring those regions.

Figure 1: Decision framework for selecting mutagenesis strategies based on available structural information and research objectives. SSM requires prior knowledge of target regions, while epPCR offers broader exploration when such information is limited.

SSM Methodologies and Technical Implementation

Molecular Basis of SSM Techniques

SSM methodologies employ different molecular strategies to introduce targeted diversity, each with distinct advantages for specific experimental scenarios. The fundamental principle involves systematically replacing specific codons with degenerate codons (typically NNK or NNN, where N represents any nucleotide and K represents G or T) to encode all 20 amino acids at the targeted position.

Oligonucleotide-directed SSM utilizes mutagenic primers containing degenerate codons at the target positions. These primers are incorporated into the plasmid through whole-plasmid amplification approaches, such as the improved two-stage PCR method that functions effectively even with difficult-to-amplify templates [5]. In this method, the first PCR stage generates a megaprimer using both mutagenic and antiprimers (non-mutagenic primers that facilitate DNA uncoiling), while the second stage employs this megaprimer for plasmid amplification [5]. This method has been successfully applied to various enzymes including P450-BM3 from Bacillus megaterium, Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Candida antarctica lipases, and Aspergillus niger epoxide hydrolase [5].

Overlap extension PCR employs two separate PCR reactions that generate gene fragments with overlapping ends containing the desired mutations, followed by a second PCR reaction where these fragments serve as templates for full-length gene assembly [7]. Synthetic oligonucleotide approaches utilize pools of synthetic oligonucleotides encoding all possible variations at targeted positions, which are then cloned into expression vectors to create comprehensive variant libraries [7].

Advanced SSM Workflow for Large-Scale Functional Analysis

Recent advances in DNA synthesis and cloning technologies have enabled unprecedented scale in SSM applications. The "Human Domainome 1" study exemplifies this scale, employing microchip-based massive parallel synthesis (mMPS) to construct a library of 1,230,584 amino acid variants across 1,248 structurally diverse protein domains [11]. This approach systematically mutated every amino acid to all other 19 amino acids at every position in each domain, achieving 91% coverage of designed substitutions.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Site Saturation Mutagenesis

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function in SSM |

|---|---|---|

| Polymerase Systems | KOD Hot Start DNA polymerase [5] | High-fidelity amplification in two-stage PCR |

| Cloning Methods | Circular Polymerase Extension Cloning (CPEC) [1] | Efficient library construction without restriction enzymes |

| Degenerate Codons | NNK (encodes all 20 aa) | Creates diversity at targeted positions |

| Vector Systems | pETM11, pCDF1b [5] [1] | Protein expression for functional screening |

| Template Preparation | Plasmid isolation from desired host | Provides backbone for mutagenesis |

| Selection Assays | Abundance protein fragment complementation assay (aPCA) [11] | High-throughput functional screening |

The functional analysis of these comprehensive variant libraries employed an abundance protein fragment complementation assay (aPCA), where each protein domain was expressed as a fusion with a fragment of an essential enzyme, and cellular growth rate served as a proxy for protein abundance [11]. This innovative selection system enabled pooled cloning, transformation, and selection of hundreds of thousands of variants across diverse proteins in single experiments, ultimately yielding reproducible abundance measurements for 563,534 variants in 522 protein domains [11].

Figure 2: Advanced SSM experimental workflow integrating modern cloning and screening methodologies for comprehensive variant functional analysis.

Applications in Protein Engineering and Drug Development

Protein Optimization and Engineering

SSM has demonstrated remarkable success in addressing diverse protein engineering challenges. In enzyme engineering, SSM has been employed to alter cofactor specificity, enhance thermostability, improve substrate specificity, and increase resistance to organic solvents. The application of SSM to Candida methylica formate dehydrogenase (cmFDH) exemplifies this approach, where two rounds of SSM at positions 195, 196, and 197 in the coenzyme binding domain yielded double mutants D195S/Q197T and D195S/Y196L that dramatically altered coenzyme specificity from NAD⺠to NADPâº, increasing catalytic efficiency for NADP⺠by approximately 5×10â´-fold [8]. Simultaneously, SSM at position 1 in the catalytic domain identified the M1L mutant with improved thermostability, exhibiting 17% residual activity after incubation at 60°C compared to wild-type enzyme [8].

The precision of SSM makes it particularly valuable for engineering specific enzyme properties when structural information guides target selection. By focusing on residues within active sites, substrate-binding pockets, or known functional motifs, researchers can create focused libraries that yield significantly higher hit rates compared to random mutagenesis approaches. This strategy efficiently explores the sequence-function landscape around critical positions without the screening burden of comprehensively random libraries.

Functional Genomics and Variant Interpretation

Beyond protein engineering, SSM has emerged as a powerful tool for functional genomics and clinical variant interpretation. Large-scale SSM studies have enabled systematic quantification of variant effects across entire protein families, providing datasets for training and benchmarking computational variant effect predictors (VEPs) [11]. These comprehensive experimental datasets reveal fundamental principles of protein structure-function relationships, such as the observation that mutations in buried core regions are generally more detrimental than surface mutations, and that mutations to proline typically exert the strongest destabilizing effects, particularly in secondary structure elements [11].

Computational saturation mutagenesis approaches extend these experimental observations through in silico analysis of all possible missense variants in target proteins. For example, a comprehensive computational saturation mutagenesis study of adducin proteins (ADD1, ADD2, ADD3) employed multiple prediction tools (AlphaMissense, Rhapsody, PolyPhen-2, and PMut) to identify high-risk variants and characterize their potential structural and functional impacts [12]. This integrated computational approach identified glycine substitutions as particularly destabilizing due to effects on backbone flexibility, and clustered high-risk mutations in known regulatory regions including phosphorylation and calmodulin-binding sites [12].

The integration of experimental and computational SSM data provides powerful frameworks for clinical variant interpretation, distinguishing pathogenic mutations from benign polymorphisms, and elucidating molecular mechanisms underlying genetic diseases. These approaches are particularly valuable for rare variants where population data may be insufficient for statistical assessment of pathogenicity.

Site saturation mutagenesis represents a powerful methodology for targeted exploration of protein sequence-function relationships, offering precision and systematic analysis that complements broader random mutagenesis approaches. The technical evolution of SSM methodologies—from early oligonucleotide-directed methods to contemporary large-scale synthetic approaches—has enabled increasingly comprehensive functional characterization of protein variants. When strategically deployed within directed evolution campaigns or functional genomics studies, SSM provides efficient interrogation of specific positions or regions, yielding fundamental insights into protein structure-function relationships and accelerating the engineering of improved biocatalysts and therapeutic proteins. As DNA synthesis technologies continue to advance and computational prediction methods become increasingly sophisticated, the integration of experimental and in silico SSM approaches will further expand our ability to interpret variant effects and engineer proteins with novel functions.

Within the broader field of directed enzyme evolution, saturation mutagenesis stands as a powerful protein engineering strategy for probing and enhancing enzyme functions such as thermostability, substrate acceptance, and enantioselectivity [5]. Unlike random mutagenesis methods such as error-prone PCR (epPCR), which introduce mutations throughout the gene, saturation mutagenesis focuses on introducing a controlled set of mutations at specific, predefined amino acid positions [5] [13]. This approach enables the creation of high-quality variant libraries of a defined size, facilitating a more efficient exploration of the sequence-function landscape [14].

While several molecular biological methods exist for performing saturation mutagenesis, Overlap Extension PCR (OE-PCR) has proven to be a particularly versatile and efficient technique [15] [16]. This method is especially valuable for introducing degenerate bases at single or multiple codon locations, generating a precise series of amino acid substitutions in the encoded protein [14]. Furthermore, improved OE-PCR protocols have overcome many limitations of traditional methods, enabling simultaneous multiple-site large fragment insertion, deletion, and substitution, even for difficult-to-amplify templates [5] [16]. This application note details the principles, protocols, and key applications of OE-PCR for saturation mutagenesis, providing researchers with a robust framework for its implementation.

Key Principles and Comparative Advantages of OE-PCR

The Fundamental Workflow of Overlap Extension PCR

Overlap Extension PCR is a multi-stage technique that uses primers with complementary ends to seamlessly join DNA fragments. The core process can be broken down into several key stages, as illustrated in the workflow below.

Comparison of Saturation Mutagenesis Methods

The table below summarizes how OE-PCR compares to other common techniques used in saturation mutagenesis.

Table 1: Comparison of common saturation mutagenesis methods.

| Method | Key Principle | Primary Advantages | Common Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overlap Extension PCR (OE-PCR) | Uses primers with complementary ends to join DNA fragments and introduce mutations [14]. | Flexible; no restriction enzyme sites needed; suitable for multi-site mutagenesis and large fragments [16]. | Can require multiple PCR steps and optimization [15]. |

| QuikChange-Style | Uses complementary primers carrying the mutation in a site-directed mutagenesis protocol [5]. | Commercially available kits; straightforward for single-site mutations. | Limited to single sites; primer design constraints; fails with difficult templates [5]. |

| Error-Prone PCR (epPCR) | Uses low-fidelity PCR conditions to introduce random mutations throughout a gene [13]. | Simple; good for introducing random diversity across the entire gene. | Lacks precision; generates mostly neutral or deleterious mutations; biased mutation spectrum [17]. |

| CRISPR-Directed Evolution | Uses CRISPR-Cas systems for precise genome editing to introduce targeted diversity [13]. | Highly precise in vivo editing; can generate complex mutant libraries in genomic context. | Higher technical complexity; potential for off-target effects [13]. |

Improved versions of OE-PCR (IOEP) have been developed to address limitations like inefficient priming of large fragments. By adding primers that bind to the vector sequence during the final amplification stage, IOEP enables exponential amplification of the overlap extension product. This enhancement significantly increases the efficiency and success rate for cloning large and difficult-to-amplify fragments, with demonstrated success for constructs as large as 12 kb [16].

Detailed Experimental Protocol

This protocol describes an improved two-stage, two-primer OE-PCR method for efficient saturation mutagenesis, adapted from published studies [5] [16].

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table lists the essential materials required to execute this protocol successfully.

Table 2: Key reagents and materials for OE-PCR saturation mutagenesis.

| Reagent/Material | Specification/Function | Example Product (Source) |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Polymerase | High-fidelity, high-processivity enzyme for accurate amplification of large/gC-rich fragments. | Q5 DNA Polymerase [18] [15], PrimeSTAR GXL [16], KOD Hot Start [5] |

| Template DNA | Plasmid containing the wild-type gene of interest. | - |

| Oligonucleotides | Mutagenic primers and external primers for exponential amplification. | - |

| Restriction Enzyme | DpnI, which cleaves methylated DNA to digest the original template plasmid post-PCR. | DpnI (NEB) [5] [18] |

| Competent E. coli | High-efficiency cells for plasmid transformation after assembly. | DH5α [5] [16], Endura Electrocompetent [18] |

| Cloning Kit/Mix | Master mix for efficient assembly of PCR fragments. | NEBuilder HiFi DNA Assembly Master Mix [18] |

Step-by-Step Procedure

Stage 1: Primer and Template Preparation

- Primer Design: Design two mutagenic primers that are complementary to the same region on opposite strands. The primers should contain the desired degenerate codon (e.g., NNK, where N is A/T/G/C and K is G/T) at the target position. Ensure primers have a melting temperature (Tm) of at least 64°C and a minimum of 8 non-overlapping bases at the 3' end [19]. For improved OE-PCR (IOEP), also design two external primers that bind to the vector sequence flanking the insertion site [16].

- Primary PCR: Perform two separate primary PCRs using a high-fidelity polymerase. The goal is to generate two overlapping DNA fragments that collectively represent the entire plasmid, with the mutation at the overlap region.

- Reaction Setup:

- Template Plasmid DNA: 1-10 ng

- Forward Primer 1 & Reverse Mutagenic Primer (for Fragment A)

- Forward Mutagenic Primer & Reverse Primer 2 (for Fragment B)

- dNTPs: 200 µM each

- DNA Polymerase: per manufacturer's instructions (e.g., 0.625 U of PrimeSTAR GXL)

- Reaction Buffer: with Mg²⺠as required

- Cycling Parameters (Touchdown):

- Reaction Setup:

- Gel Purification: Verify the size and purity of the two PCR fragments by agarose gel electrophoresis. Excise the correct bands and purify the DNA using a gel extraction kit.

Stage 2: Overlap Extension and Exponential Amplification

- Overlap Extension Reaction:

- Combine the two purified fragments (e.g., 50-100 ng of each) in a single tube. For IOEP, also include the two external primers at this stage [16].

- Use a high-fidelity polymerase and the same cycling parameters as in the primary PCR, but without the initial denaturation step. The overlapping ends of the fragments will anneal and extend, forming a full-length circular plasmid.

- DpnI Digestion: To eliminate the original methylated template plasmid, treat the PCR product with DpnI (10 U per 50 µL reaction) for 1-2 hours at 37°C [5].

- Purification: Purify the DpnI-treated DNA using a standard PCR clean-up kit.

Stage 3: Cloning and Transformation

- Transformation: Transform 2-5 µL of the purified assembly product into competent E. coli DH5α cells using standard heat-shock or electroporation methods.

- Screening and Validation: Plate cells on selective media and incubate overnight. Screen resulting colonies by colony PCR or restriction digest. Validate the sequence of the mutated gene by Sanger sequencing of plasmid DNA from positive clones.

Critical Factors for Success

- Primer Design and Localization: Optimal primer design is critical. The direction and design of the "antiprimer" (a non-mutagenic primer used to complete complementary extension) are determining factors in successfully amplifying difficult templates [5]. Ensure sufficient overlap length (typically 15-25 bp) with high homology.

- Polymerase Selection: The choice of DNA polymerase significantly impacts success. Use a high-fidelity, high-processivity enzyme (e.g., Q5, KOD, PrimeSTAR GXL) to improve the quality and yield of full-length amplification, especially for large or complex fragments [15] [16].

- Handling Difficult Templates: For plasmids that are difficult to amplify (e.g., those with high GC-content or secondary structures), the improved two-stage PCR method, which uses the initial product as a megaprimer in a second PCR with adjusted annealing temperatures, has proven highly effective [5].

Applications in Directed Evolution

OE-PCR-based saturation mutagenesis is a cornerstone of modern directed evolution campaigns. Its primary applications include:

- Iterative Saturation Mutagenesis (ISM): This systematic strategy involves repeatedly performing saturation mutagenesis at different predefined sites (or "hotspots") in an enzyme. ISM is highly effective for optimizing properties like enantioselectivity and thermostability by exploring the combinatorial active-site saturation test (CAST) or B-FIT concepts [5].

- Deep Mutational Scanning: Saturation mutagenesis libraries can be used in massively parallel reporter assays (MPRAs) to functionally characterize thousands of single nucleotide variants in regulatory elements, aiding in the interpretation of disease-associated noncoding variants [17].

- Multi-Fragment Assembly: Improved OE-PCR enables the simultaneous insertion, deletion, or substitution of multiple large DNA fragments at different sites in a single vector, a powerful capability for complex metabolic engineering and synthetic biology projects [16].

Overlap Extension PCR provides a robust, flexible, and efficient platform for conducting saturation mutagenesis. Its ability to precisely randomize single or multiple amino acid positions, coupled with recent improvements that enhance its efficiency and expand its application to large DNA fragments, makes it an indispensable tool in the directed evolution workflow. By following the detailed protocol and considerations outlined in this application note, researchers can effectively leverage OE-PCR to engineer proteins with novel and enhanced functions, accelerating progress in biotechnology, drug development, and basic research.

Key Applications in Protein Engineering and Synthetic Biology

Error-prone PCR (epPCR) and site-saturation mutagenesis (SSM) represent two cornerstone methodologies in the field of protein engineering. These techniques facilitate the directed evolution of proteins by generating genetic diversity, enabling the development of enzymes and biosynthetic proteins with enhanced properties such as catalytic activity, stability, and substrate specificity. Within the context of a broader thesis on mutagenesis research, this application note details the key applications, methodologies, and reagent solutions that underpin their successful implementation in modern synthetic biology and drug development pipelines. The strategic application of these methods allows researchers to explore vast sequence-function landscapes efficiently [20].

Comparative Analysis of Mutagenesis Techniques

The selection of a mutagenesis strategy is critical to the success of a protein engineering campaign. Error-prone PCR introduces random mutations throughout a gene, making it ideal for exploring a wide mutational space when no prior structural knowledge is available. In contrast, Site-Saturation Mutagenesis allows for the focused randomization of specific codon locations, providing a more controlled and comprehensive exploration of key residues, often those implicated in catalytic activity or substrate binding [14] [20]. The following table summarizes their core characteristics and applications.

Table 1: Key Characteristics of epPCR and SSM

| Feature | Error-Prone PCR (epPCR) | Site-Saturation Mutagenesis (SSM) |

|---|---|---|

| Mutagenesis Scope | Random mutations across the entire gene sequence [20] | Focused mutagenesis at one or multiple pre-defined codon positions [14] [21] |

| Primary Application | Directed evolution without requiring structural data; improving general properties like stability [22] [20] | Investigating or optimizing specific active sites, binding pockets, or functional residues [14] [5] |

| Library Design | Uncontrolled; diversity depends on error-rate of polymerase [23] | Controlled and precise; uses degenerate codons (e.g., NNK) to access all possible amino acids at a site [14] [21] |

| Typical Throughput | Requires screening of large libraries (>10^5 variants) [22] | Library size is manageable and defined (theoretical maximum of 20 variants per codon) [14] |

| Integration with Automation | Well-suited for automated library construction and screening in biofoundries [24] | Highly amenable to automation for primer design, library construction, and high-throughput screening [25] [24] |

| Common Challenge | Biased mutation spectrum (preference for transitions) [17] | Requires prior knowledge (e.g., structural data) to select impactful positions for randomization [26] |

The quantitative performance of these methods is evidenced in numerous studies. For instance, in one saturation mutagenesis study of 20 disease-associated regulatory elements, researchers successfully measured the functional effects of over 30,000 single nucleotide substitutions and deletions, achieving near-complete coverage of all potential SNVs [17]. In a separate application, a combined directed evolution approach was used to co-evolve β-glucosidase for both enhanced activity and organic acid tolerance, leading to a 4.3-fold improvement in enzyme activity [26].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Site-Saturation Mutagenesis by Overlap Extension PCR

This protocol describes the creation of a high-quality variant library by introducing degenerate codons at specific positions via overlap extension PCR [14] [21].

Procedure:

- Primer Design: Design mutagenic primers containing degenerate codons (e.g., NNK or NNN, where K = G/T) at the target amino acid position(s). The primers must be complementary and have sufficient overlap for the extension reaction.

- First PCR Amplification: Perform two separate primary PCR reactions to generate overlapping gene fragments.

- Reaction A: Amplify the 5' fragment of the gene using a forward plasmid-specific primer and the reverse mutagenic primer.

- Reaction B: Amplify the 3' fragment using the forward mutagenic primer and a reverse plasmid-specific primer.

- Purification: Purify both PCR products from Step 2 to remove residual primers and polymerase.

- Overlap Extension PCR: Combine the purified fragments from Reaction A and B. In the first few cycles (without external primers), the overlapping ends of the fragments anneal and extend, forming full-length mutant genes. Then, add the external forward and reverse primers to amplify the full-length product.

- Digestion and Ligation: Digest the overlap extension PCR product and the target plasmid with the appropriate restriction enzymes. Purify the fragments and ligate the mutant gene insert into the plasmid backbone.

- Transformation and Library Creation: Transform the ligated product into a competent E. coli strain. Plate the cells on selective media to create the mutant library for subsequent screening [14].

Protocol 2: Error-Prone PCR for Random Mutagenesis

This protocol outlines the generation of a random mutant library using error-prone PCR, which is suitable for whole-gene diversification without a specific target site [22] [20].

Procedure:

- Reaction Setup: Set up the PCR reaction using a template plasmid containing the wild-type gene. To promote a high error rate, use a polymerase with low fidelity (e.g., Taq polymerase) and modify standard conditions:

- Increase the concentration of MgClâ‚‚ (e.g., 7 mM).

- Add a small, optimized concentration of MnClâ‚‚ (e.g., 0.5 mM).

- Use unbalanced dNTP concentrations (e.g., increase dATP and dTTP relative to dGTP and dCTP).

- Amplification: Run the PCR with a standard thermocycling program suitable for the gene of interest.

- Product Purification: Purify the error-prone PCR product to remove enzymes and unbalanced dNTPs.

- Downstream Cloning: The purified epPCR product can be cloned into an expression vector using various methods:

- Restriction/Ligation: If the product has terminal restriction sites.

- Homologous Recombination: In yeast or Bacillus subtilis systems, the product can be co-transformed with a linearized plasmid for in vivo assembly [22].

- Gibson Assembly: An isothermal, single-tube method based on overlapping homology.

- Library Transformation: Transform the assembled DNA into a suitable host organism to create the mutant library for high-throughput screening.

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the logical sequence and key decision points in a directed evolution campaign utilizing epPCR and SSM.

Decision and Workflow for Directed Evolution

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Successful execution of mutagenesis experiments relies on a suite of specialized reagents and tools. The following table details essential materials and their functions.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for Mutagenesis and Screening

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Degenerate Oligonucleotides | Primers containing degenerate bases (NNK) for introducing all possible amino acid substitutions at a target codon in SSM [5] [21]. | Synthesized commercially; NNK reduces codon redundancy (32 codons for 20 amino acids). |

| Low-Fidelity Polymerase | Enzyme used in epPCR to introduce random mutations during DNA amplification [17] [20]. | Taq polymerase is commonly used under modified buffer conditions to increase error rates. |

| High-Fidelity Polymerase | Enzyme used in SSM protocols (e.g., Overlap Extension PCR) to minimize unwanted background mutations during amplification [5]. | Phusion or KOD Hot Start DNA polymerase are often preferred. |

| DpnI Restriction Enzyme | Digests the methylated parental DNA template post-PCR, enriching the final product for newly synthesized mutant DNA [5] [23]. | Critical for site-directed mutagenesis protocols to reduce background. |

| Specialized Vectors | Plasmid backbones optimized for cloning mutant libraries and expressing proteins in relevant hosts. | pET series for E. coli expression; integration plasmids for B. subtilis [17] [22]. |

| Competent Cells | High-efficiency bacterial or yeast cells for transforming mutant library DNA. | E. coli DH5α for plasmid propagation; specialized strains for protein expression. |

| Mass Photometry | A label-free technique for detecting molecular interactions and complex formation in solution, useful for screening binding events in libraries [21]. | Used to assess SpyTag-SpyCatcher binding in library screens. |

| Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting (FACS) | An ultra-high-throughput screening method for isolating variant-containing cells based on a fluorescent signal linked to the desired function [25]. | Enables screening of libraries with >100,000 variants in a few days. |

| Massively Parallel Reporter Assays (MPRAs) | Enables functional measurement of thousands of genetic variants (e.g., from saturation mutagenesis) simultaneously [17]. | Applied to saturation mutagenesis of 20 regulatory elements. |

| A-987306 | A 987306 is a potent, selective, and orally active histamine H4 receptor antagonist for research. It is For Research Use Only. Not for human consumption. | |

| iMAC2 | iMAC2, CAS:335166-00-2, MF:C19H22Br2Cl2FN3, MW:542.1 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Understanding Mutational Bias and Library Quality

In the field of protein engineering and functional genomics, error-prone PCR (epPCR) site saturation mutagenesis serves as a foundational technique for generating genetic diversity. This process is central to directed evolution experiments and deep mutational scanning (DMS) studies, which aim to elucidate genotype-phenotype relationships by systematically analyzing protein variants [27]. However, the practical application of these techniques is frequently compromised by mutational bias—systematic non-randomness in the types and locations of introduced mutations. Such biases can significantly skew library composition, reduce functional diversity, and ultimately lead to misleading biological conclusions or inefficient engineering campaigns.

The integrity of any downstream analysis or selection process is fundamentally dependent on the quality of the mutant library, which encompasses the evenness of variant distribution, the accurate representation of all intended mutations, and the minimization of non-functional sequences. A comprehensive understanding of the sources of mutational bias and the implementation of robust protocols to control library quality are therefore essential for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals working in this domain. This document provides a detailed examination of these critical aspects, supported by structured data and actionable protocols.

Quantifying and Understanding Mutational Bias

Mutational bias refers to the non-stochastic deviations from theoretical mutation frequencies that occur during library construction. Recognizing and quantifying these biases is the first step toward mitigating their effects.

The following table summarizes the major sources of bias inherent to traditional error-prone PCR methods:

Table 1: Key Sources and Effects of Mutational Bias in Error-Prone PCR

| Source of Bias | Description | Impact on Library |

|---|---|---|

| Polymerase Specificity | Different DNA polymerases have distinct error signatures and preferences for specific nucleotide misincorporations [28]. | Skews the mutational spectrum (e.g., over-representation of transitions AG, TC over transversions) [29]. |

| Sequence Context | The local DNA sequence (e.g., high or low GC content) can influence the error rate at a given position [30]. | Uneven mutation distribution across the target gene, leading to "cold spots" and "hot spots". |

| PCR Conditions | Factors like MnClâ‚‚ concentration, unbalanced dNTP ratios, and increased MgClâ‚‚ are used to enhance error rates [23]. | Can exacerbate polymerase-specific biases and introduce additional sequence-specific artifacts if not carefully optimized. |

| Codon Degeneracy | Using NNN (where N is any base) randomization results in 32 codons encoding only 20 amino acids, with different stop codon frequencies [27]. | Non-uniform amino acid sampling; over-representation of some amino acids and multiple stop codons. |

The bias introduced by Taq polymerase, for instance, is particularly well-documented, with a much higher observed mutation rate at A/T bases compared to C/G bases [28] [27]. Furthermore, early saturation mutagenesis protocols that rely on doped or degenerate primers are susceptible to biases arising from DNA sequence, G/C content, and primer quality, which can distort the final library composition [30].

Impact of Mutational Bias on Library Quality and Experimental Outcomes

A biased library directly undermines the efficiency and success of a protein engineering or DMS campaign. An uneven distribution of variants means that the experimental screening effort may be wasted on characterizing an overabundance of certain mutations while missing others entirely. This sparse and non-uniform sampling of sequence space makes it difficult to identify rare, beneficial mutations or to accurately map the protein's fitness landscape [31]. Consequently, the conclusions drawn about which residues are critical for function, stability, or binding may be incomplete or statistically unreliable.

Strategies and Reagents for Reducing Mutational Bias

Several advanced methodological strategies have been developed to counteract mutational bias and construct higher-quality libraries.

Experimental Methods for Improved Library Construction

The table below compares several key protocols designed to generate more balanced mutant libraries.

Table 2: Comparison of Protocols for Reducing Mutational Bias

| Method | Core Principle | Key Advantage | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polymerase Blending | Using a combination of low-fidelity polymerases (e.g., Taq and Mutazyme) with complementary mutational spectra [28]. | Reduces the specific bias inherent to any single enzyme, creating a more uniform mutation distribution. | [28] |

| Megaprimer PCR | A two-stage, whole-plasmid PCR method that uses a mutagenic primer and a non-mutagenic "antiprimer" to generate a megaprimer [5]. | Overcomes difficulties with amplifying complex templates and avoids problems of primer self-pairing. | [5] |

| SLUPT (Synthesis of Libraries via dU-containing PCR Templates) | Utilizes a dU-containing single-stranded DNA template generated by PCR. Mutagenic primers are extended and ligated, followed by template degradation [32]. | High efficiency, very low background from the starting sequence, and excellent stoichiometric balance of nucleotides at varied positions. | [32] |

| One-Pot Saturation Mutagenesis | Employs strand-specific nicking enzymes to create ssDNA templates, followed by synthesis with degenerate primers and degradation of the wild-type strand [23]. | Allows customizable, multi-site saturation mutagenesis with high coverage and mutational efficiency in a single tube. | [23] |

| Semiconductor-Based Synthesis | Uses programmable semiconductor chips to synthesize thousands of predefined oligonucleotides in parallel [30]. | Enables complete user control over every variant in the library, eliminating synthesis-level bias and stop codons. | [30] |

These methods represent a significant evolution from purely random approaches. For example, the one-pot saturation mutagenesis method allows researchers to tile a region of interest with multiple primers, each containing three consecutive randomized bases (NNN) at a specific codon, enabling comprehensive and parallel mutagenesis [23]. Meanwhile, the semiconductor-based synthesis represents a shift towards fully rational library design, where the mutagenesis is "less random" and directly tailored to the researcher's specifications [30].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful library construction relies on a suite of specialized reagents. The following table details key solutions and their functions.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Saturation Mutagenesis

| Research Reagent | Function in Library Construction |

|---|---|

| Low-Fidelity Polymerase Blends | Engineered mixes of polymerases (e.g., from commercial kits) designed to reduce mutational bias during error-prone PCR [28] [27]. |

| Strand-Nicking Restriction Enzymes | Enzymes like Nt.BbvCI and Nb.BbvCI that nick specific DNA strands to create single-stranded templates for methods like one-pot mutagenesis [23]. |

| dU-containing dNTP Mixes | Nucleotide mixes used in PCR to create a template strand that can be selectively degraded by enzymes like Uracil DNA Glycosylase (UDG), as used in SLUPT and PFunkel methods [32] [23]. |

| Lambda Exonuclease | An enzyme that degrades one strand of double-stranded DNA, used in the SLUPT protocol to generate single-stranded DNA from a phosphorylated PCR product [32]. |

| Programmable Oligo Synthesis Platforms | Semiconductor-based systems that synthesize precisely defined oligonucleotide libraries, enabling the creation of bias-free, user-defined variant pools [30]. |

| M8-B | M8-B, MF:C22H25ClN2O3S, MW:433.0 g/mol |

| VU0364572 TFA | VU0364572 TFA, MF:C23H32F3N3O5, MW:487.5 g/mol |

A Detailed Protocol for One-Pot Saturation Mutagenesis

The following workflow and detailed protocol for one-pot saturation mutagenesis is adapted from Wrenbeck et al. and represents a robust method for generating high-quality, customizable libraries [23].

Diagram 1: One-Pot Saturation Mutagenesis Workflow

Step-by-Step Methodology

Part 1: Preparation of ssDNA Template

- Nick the Wild-type Plasmid: Set up a nicking reaction using the wild-type plasmid as a template. Use the restriction enzyme Nt.BbvCI (if the goal is to ultimately nick the sense strand first). Incubate at 37°C for 1 hour.

- Degrade the Nicked Strand: To the same tube, add Exonuclease III (ExoIII) and Exonuclease I (ExoI). ExoIII will processively degrade the nicked strand from the nick site, while ExoI will clean up any remaining single-stranded DNA. Incubate at 37°C for 1 hour, followed by enzyme inactivation at 70°C for 10-15 minutes. The product is a single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) template.

Part 2: Synthesize the First Mutant Strand

- Design Mutagenic Primers: Design a set of primers that tile across the region of interest. Each primer should contain a central

NNNtriplet to randomize the target codon, flanked by perfectly complementary wild-type sequence (~20-25 bp on each side). The primers must be the same sense as the degraded strand from Part 1. - Primer Annealing and Extension: In a new PCR tube, combine the ssDNA template from Part 1 with the pool of degenerate primers, high-fidelity Phusion polymerase, and dNTPs. Use a low primer-to-template ratio to ensure that, on average, only one primer binds to each template molecule. Run a limited number of PCR cycles (e.g., 10-15) to synthesize the complementary mutant strand. The product is a heteroduplex plasmid with one wild-type and one mutant strand.

- Purification: Purify the PCR product using a DNA clean-up kit to remove excess primers, enzymes, and dNTPs.

Part 3: Degrade the Wild-type Template Strand

- Nick the Wild-type Strand: Treat the purified heteroduplex plasmid from Part 2 with the other BbvCI variant (Nb.BbvCI), which will nick the strand opposite to the one nicked in Part 1 (the remaining wild-type strand). Incubate at 37°C for 1 hour.

- Degrade the Wild-type Strand: Add ExoIII and ExoI to degrade the nicked wild-type strand. Incubate at 37°C for 1 hour, followed by heat inactivation. This leaves the first synthesized mutant strand as the new template.

Part 4: Synthesize the Second Mutant Strand

- Second Strand Synthesis: To the reaction from Part 3, add a universal primer (complementary to the vector backbone) and high-fidelity Phusion polymerase. This step synthesizes the second strand, using the mutant strand as a template, resulting in a double-stranded mutant plasmid.

- Remove Template: Digest the product with DpnI to cleave any residual methylated wild-type starting plasmid that may have carried through.

- Library Completion: Transform the final DpnI-treated product into competent E. coli cells. After outgrowth, harvest the cells to obtain the plasmid library, which is now ready for quality control and functional screening.

Quality Assessment and Validation of Mutant Libraries

Rigorous quality control (QC) is non-negotiable for ensuring that the constructed library accurately represents the intended diversity and is free from major biases or errors.

Key Quality Control Metrics

- Sequencing Depth: The pre-selection library must be deeply sequenced using next-generation sequencing (NGS) to obtain a quantitative count of each variant. A minimum of 100-200 reads per variant is often required for reliable quantification [23]. Inadequate depth will fail to detect rare but potentially important variants.

- Assessment of Initial Bias: The NGS data from the pre-selection input library must be analyzed to determine the evenness of variant representation. This baseline is critical for distinguishing a mutation that is truly detrimental from one that was simply underrepresented from the start [31].

- Error Correction with UMIs: To mitigate the effects of PCR and sequencing errors, Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) should be incorporated. UMIs are short, random DNA sequences attached to each original DNA molecule before amplification. Bioinformatic clustering of reads that share the same UMI allows for the computational correction of errors that occurred during library amplification and sequencing, resulting in a much cleaner and more accurate dataset [31].

Advanced Applications: Linking Method to Discovery

The transition from biased, low-quality libraries to controlled, high-fidelity libraries has enabled groundbreaking applications in basic and applied research. High-quality DMS studies, powered by advanced mutagenesis techniques, have allowed researchers to:

- Map antibody-antigen interfaces with single-residue resolution, identifying critical binding hotspots for therapeutic antibody optimization [31].

- Predict viral evolution by comprehensively identifying mutations in viral proteins (e.g., SARS-CoV-2 spike protein) that confer escape from neutralizing antibodies, thereby guiding vaccine design [27].

- Understand genetic interactions (epistasis) by revealing how the functional effect of one mutation depends on the presence of other mutations within the same gene or in different genes [27].

Diagram 2: From Controlled Synthesis to Discovery

The use of programmable semiconductor chips, for instance, exemplifies this progression. This technology allows for the synthesis of a pre-defined oligo pool where every variant is specified by the researcher, effectively merging large-scale DNA synthesis with rational design [30]. This approach directly addresses the core issue of bias, making the directed evolution process quicker, more efficient, and more reliable, as illustrated in the pathway above. This is particularly transformative for applications like therapeutic antibody engineering, where the goal is to find an optimal candidate in a vast sequence space.

From Theory to Bench: Practical Protocols for Library Construction and Screening

Site-saturation mutagenesis is a powerful directed evolution strategy for generating comprehensive variant gene libraries by introducing a precise series of amino acid substitutions at specific codon locations in a protein encoding sequence [14]. This technique uses degenerate oligonucleotide primers to systematically replace targeted codons, enabling researchers to explore structure-function relationships and improve protein properties such as thermostability, substrate specificity, and enzymatic activity without requiring prior structural knowledge [33]. When performed via overlap extension PCR, this method creates high-quality libraries that access amino acid substitutions unlikely to emerge through random mutagenesis techniques like error-prone PCR [14]. This protocol details the implementation of site-saturation mutagenesis within a broader research framework investigating error-prone PCR and saturation mutagenesis methodologies for protein engineering and drug development applications.

Principle of the Method

Site-saturation mutagenesis by overlap extension PCR utilizes degenerate codon representations (such as NNK, where N represents any nucleotide and K represents G or T) to randomize specific amino acid positions [5]. The NNK codon set encodes all 20 canonical amino acids while reducing redundancy from 64 to 32 codons and excluding two of the three stop codons [34]. The method employs two consecutive PCR stages: first, gene fragments containing mutated sequences are amplified using external primers and complementary internal primers bearing degenerate codons; second, these fragments undergo overlap extension where complementary ends anneal and are extended to form full-length mutated genes [14]. Compared to commercial site-directed mutagenesis kits that sometimes fail with difficult-to-amplify templates, this overlap extension approach demonstrates improved efficiency and reliability across various enzyme systems including P450-BM3, lipases, and epoxide hydrolases [5].

Table 1: Comparison of Mutagenesis Approaches

| Method | Key Features | Limitations | Best Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Site-Saturation Mutagenesis | Systematic codon replacement; focused diversity; high quality variants [14] | Requires screening; limited to targeted residues | Exploring specific active sites or regions [5] |

| Error-Prone PCR | Genome-wide random mutations; simple protocol [34] | Mutation bias; predominantly point mutations [34] | Broad exploration without structural data |

| Gene Site Saturation Mutagenesis (GSSM) | All possible single amino acid substitutions [33] | Resource-intensive screening | Comprehensive protein mapping |

Experimental Protocols

Primer Design and Calculation

Effective primer design is critical for successful site-saturation mutagenesis. Mutagenic primers should be 25-45 nucleotides long with the degenerate codon positioned near the center. Flanking sequences of 10-15 bases on each side ensure proper annealing. The NNK degeneracy is preferred over NNN as it reduces the codon set from 64 to 32 while maintaining coverage of all 20 amino acids and only one stop codon [34].

For multi-site saturation mutagenesis, primers must be designed to avoid complementarity that could form hairpins or primer-dimers. Melting temperatures (Tm) should be optimized for the specific PCR system, typically ranging between 60-72°C [5]. Table 2 provides example primers from actual studies.

Table 2: Exemplary Mutagenic Primers for Saturation Mutagenesis

| Target | Primer Name | Sequence (5' to 3') | Tm (°C) | Mutation Site |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P450-BM3 | F87NNKF | GCAGGAGACGGGTTANNKACAAGCTGGACGCATG [5] | 64 | F87 |

| P450-BM3 | F87NNKR | CATGCGTCCAGCTTGTMNNTAACCCGTCTCCTGC [5] | 64 | F87 |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa Lipase | M16-L17 NNK-PAL-F | CTGGCCCACGGCNNKNNKGGCTTCGACAAC [5] | 65 | M16-L17 |

Step-by-Step Procedure

Stage 1: Initial Fragment Amplification

Reaction Setup: Prepare two separate PCR reactions for each mutagenesis target:

- Reaction A: Template DNA (10-100 ng), Forward external primer (0.2-0.5 µM), Reverse mutagenic primer (0.2-0.5 µM)

- Reaction B: Template DNA (10-100 ng), Forward mutagenic primer (0.2-0.5 µM), Reverse external primer (0.2-0.5 µM)

PCR Conditions:

- Initial denaturation: 95°C for 2-5 minutes

- 25-30 cycles of:

- Denaturation: 95°C for 15-30 seconds

- Annealing: Tm of primers (55-68°C) for 30-60 seconds

- Extension: 72°C for 15-30 seconds per kb

- Final extension: 72°C for 5-10 minutes

Product Purification: Separate PCR products by agarose gel electrophoresis and extract using a gel purification kit. Quantify DNA concentration spectrophotometrically [14].

Stage 2: Overlap Extension PCR

Hybridization Reaction: Combine approximately 100-200 ng each of purified fragments A and B in a PCR tube without primers. Add PCR reagents except primers. Perform 5-10 cycles of:

- Denaturation: 95°C for 30 seconds

- Annealing: 45-55°C for 30-60 seconds

- Extension: 72°C for 30-60 seconds per kb

Full-Length Amplification: Add external primers (0.2-0.5 µM each) to the same tube. Perform 25-30 cycles using the same parameters as initial fragment amplification.

Product Analysis: Verify the full-length product by agarose gel electrophoresis against appropriate molecular weight standards [14] [5].

The following workflow diagram illustrates the complete experimental procedure:

Library Construction and Analysis

Cloning: Purify the overlap extension PCR product and clone into an appropriate expression vector using restriction enzyme digestion and ligation, or more efficient methods like Circular Polymerase Extension Cloning (CPEC) which can improve library coverage [1].

Transformation: Introduce the ligated DNA into competent Escherichia coli cells (such as DH5α or XL1-Blue) by electroporation or heat shock. Plate onto selective media and incubate overnight [5].

Library Quality Assessment:

- Sequence Verification: Sequence 10-20 random clones to determine mutation rate and diversity.

- Library Size: Ensure sufficient colonies to cover 95-99% of possible variants. The theoretical library size for a single position is 32 codon variants; for multiple positions, library size increases exponentially [34].

- Functional Screening: Express variants and screen for desired functional improvements using high-throughput assays.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Site-Saturation Mutagenesis

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function & Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Polymerases | KOD Hot Start DNA Polymerase [5], Phusion High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase [23] | High-fidelity amplification with proofreading activity for accurate library generation |

| Cloning Systems | T7 ligase [1], CPEC method [1] | Efficient ligation of PCR products into expression vectors; CPEC avoids restriction enzyme dependence |

| Vectors | pETM11 series [5], pCDF1b [1] | Protein expression vectors with appropriate selection markers and promoter systems |

| Competent Cells | E. coli DH5α [5], E. coli TOP10 [1] | High-efficiency transformation strains for library construction and propagation |

| Degenerate Codons | NNK (N=A/C/G/T, K=G/T) [34] | Encodes all 20 amino acids with only one stop codon; optimal for saturation mutagenesis |

| Selection Antibiotics | Ampicillin, Chloramphenicol [5] [35] | Selective pressure for plasmid maintenance during library construction |

| ML266 | ML266, MF:C24H22BrN3O4, MW:496.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| (S,R,S)-AHPC-Me hydrochloride | (S,R,S)-AHPC-Me hydrochloride, CAS:1948273-03-7, MF:C23H33ClN4O3S, MW:481.1 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Applications and Concluding Remarks

Site-saturation mutagenesis by overlap extension PCR provides a robust methodological framework for systematic protein engineering. This technique enables comprehensive exploration of sequence-function relationships at targeted positions, often revealing beneficial mutations inaccessible through random mutagenesis approaches [33]. When implemented within iterative saturation mutagenesis (ISM) strategies, where beneficial mutations from initial rounds are recombined and subjected to further randomization, this approach can efficiently navigate protein fitness landscapes [5].

The integration of site-saturation mutagenesis with high-throughput screening platforms and next-generation sequencing technologies creates powerful pipelines for directed evolution campaigns in both academic research and industrial drug development. As synthetic biology advances toward precision design, methodologies for constructing high-quality mutant libraries with comprehensive coverage and minimal bias remain essential for elucidating functional motifs in biomacromolecules and engineering novel functionalities [34].

Optimizing Error-Prone PCR to Control Mutation Rate and Reduce Bias

Error-prone PCR (epPCR) serves as a fundamental technique in directed evolution for generating genetic diversity from a single gene template. By introducing random mutations during PCR amplification, researchers can create comprehensive mutant libraries suitable for screening improved protein variants. The core principle involves utilizing low-fidelity DNA polymerase under conditions that promote misincorporation of nucleotides, thereby achieving mutation rates typically ranging from 1 to 20 base substitutions per gene [35]. Within the broader context of saturation mutagenesis research, epPCR provides a straightforward method for exploring sequence-function relationships without requiring prior structural knowledge, making it particularly valuable for initial diversification phases in protein engineering campaigns. However, the practical implementation of epPCR presents significant challenges in controlling mutation frequency and minimizing biochemical biases that can skew library representation and compromise screening effectiveness. This application note provides detailed methodologies and quantitative frameworks for optimizing epPCR parameters to achieve predictable mutation rates while mitigating common sources of bias.

Critical Parameters for Controlling Mutation Rates

Establishing Desired Mutation Frequencies

The mutation frequency in epPCR libraries profoundly impacts the probability of discovering improved variants. Libraries with very low mutation rates (m < 2) contain mostly single mutants, simplifying the identification of beneficial mutations but potentially missing synergistic effects. Conversely, highly mutated libraries (m > 8) enable exploration of multi-site interactions but dramatically reduce the fraction of functional clones [35]. Quantitative analysis demonstrates that the fraction of functional clones decreases exponentially with increasing mutation frequency up to approximately m = 8, though this trend may reverse in hypermutated libraries (m > 20) where functional clones occur at unexpectedly high frequencies [35].

Table 1: Relationship Between Mutation Frequency and Library Characteristics

| Average Mutations per Gene (m) | Functional Clones | Screening Considerations | Typical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1.7 - 2 | High percentage | Identifies single beneficial mutations | Initial rounds, stability optimization |

| 3 - 8 | Exponential decrease with m | Balanced diversity/function | Affinity maturation, substrate specificity |

| > 8 - 22.5 | Very low (≈0.17% at m=22.5) but functional clones present | Requires high-throughput screening | Exploring distant sequence space, multi-site synergies |

For most applications, maintaining mutation rates between 1-5 amino acid substitutions per protein provides an optimal balance between diversity and functionality. In a case study targeting a single-chain Fv antibody, libraries with m = 1.7, 3.8, and 22.5 all yielded clones with improved affinity after fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS), with the moderate error rate library (m = 3.8) providing the greatest affinity improvement [35].

Biochemical Optimization of Mutation Rate

Traditional epPCR protocols employ several biochemical manipulations to increase error rates, including: (1) increased concentration of Taq polymerase, (2) extended PCR extension time, (3) elevated concentration of MgClâ‚‚ (which stabilizes non-complementary base pairs), (4) increased concentration of dNTPs, and/or (5) addition of MnClâ‚‚ [23]. The use of Taq polymerase with an in-house dNTP mixture has been successfully implemented to achieve approximately 2% point mutation rates, with 3rd-to-5th-round PCR products typically selected for optimal diversity [36].

More recently, commercial random mutagenesis kits such as the GeneMorph II Random Mutagenesis kit have provided standardized platforms for controlling mutation frequency through proprietary enzyme blends and buffer formulations [1]. These systems offer more reproducible mutational spectra compared to traditional in-house formulations.

Table 2: DNA Polymerase Fidelity Measurements Under Standard Conditions

| Polymerase | Per-Base Error Rate (×10â»â¶) | Relative Fidelity | Dominant Substitution Types |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kapa HF | 5.9 | High | C>T, G>A |

| Taq-HS | 29.3 | Low | A>G, T>C |

| Encyclo | 10.6 | Medium | A>G, T>C |

| SD-HS | 21.6 | Low | A>T |

| Phusion | 0.9 | Very High | Not determined |

Error rate data adapted from quantitative measurements using unique molecular identifier tagging and high-throughput sequencing [3]. Polymerases cluster into distinct categories based on their substitution preferences, with some favoring transitions (C>T and G>A) while others predominantly introduce transversions.

Technical Approaches to Minimize PCR Bias

PCR amplification bias represents a significant challenge in epPCR library generation, potentially leading to uneven representation of sequence variants. The primary sources of bias include:

- Sequence-dependent amplification efficiency: Templates with high AT- or GC-content often amplify less efficiently, leading to underrepresentation in final libraries [37]. This effect becomes exponentially exaggerated over multiple cycles.

- Taq polymerase errors: Dominant sequence artifacts occur at rates approximately matching theoretical expectations (2-3.3×10â»âµ errors per nucleotide per duplication) [38]. These errors particularly impact diversity estimates in deep mutational scanning studies.

- Chimeric sequences and heteroduplex molecules: These artifacts can comprise up to 13% of sequences in standard 35-cycle amplifications, falsely inflating diversity measurements [38].

- Primer design limitations: Self-complementarity, hairpin formation, and palindromic sequences in primers can dramatically reduce amplification efficiency of specific variants [5].

Practical Strategies for Bias Reduction

Modification of standard amplification protocols can significantly reduce epPCR bias. Critical adjustments include:

- Cycle number optimization: Limiting amplification to 15-18 cycles followed by a reconditioning PCR step (3 additional cycles in a fresh reaction mixture) reduces heteroduplex formation and Taq error accumulation [38]. This modification decreased unique 16S rRNA sequences from 76% to 48% after chimera and error correction, indicating more accurate diversity representation.

- Polymerase selection: KAPA HiFi DNA polymerase demonstrates superior performance in amplifying regions with extreme GC-content, providing more uniform genomic coverage compared to traditional enzymes [37]. For AT-rich templates, additives like tetramethyleneammonium chloride (TMAC) increase melting temperature stability when used with compatible polymerases.

- Cloning method improvements: Traditional ligation-dependent cloning processes (LDCP) inevitably lose potential mutants during restriction digestion and ligation. Circular polymerase extension cloning (CPEC) provides an efficient restriction-free alternative, where high-fidelity DNA polymerase extends overlapping regions between insert and vector to form circular molecules [1]. In direct comparisons, CPEC yielded greater variant diversity from the same epPCR products.

- Unique molecular identifiers (UMIs): Incorporating random oligonucleotide tags before amplification enables bioinformatic correction of amplification biases during sequencing analysis [3]. Recent advances include homotrimeric nucleotide block UMIs that provide error-correcting capabilities through majority voting mechanisms, significantly improving molecular counting accuracy [39].

Integrated Experimental Protocols

Standardized Error-Prone PCR Protocol

Materials: Template DNA (10-100 ng), mutagenic primers, Taq DNA polymerase or specialized mutagenesis enzyme blend, 10× mutagenesis buffer (with Mg²âº), dNTP mix, MnClâ‚‚ (if required for error rate adjustment)

Procedure:

- Prepare reaction mixture with final concentrations of:

- 1× mutagenesis buffer

- 0.2 mM dATP and dGTP

- 1 mM dCTP and dTTP (nucleotide imbalance promotes misincorporation)

- 0.5 mM MnClâ‚‚ (optional for increased error rate)

- 5 U Taq polymerase

- 0.5 µM forward and reverse primers

- Template DNA (20-50 ng)

Perform thermal cycling:

- Initial denaturation: 94°C for 2 minutes

- 25-30 cycles of:

- Denaturation: 94°C for 15 seconds

- Annealing: 50-68°C (primer-specific) for 30 seconds

- Extension: 72°C for 1 minute per kb

- Final extension: 72°C for 5 minutes

Purify PCR products using silica membrane columns or magnetic beads.

Quantify mutation rate by sequencing 4-20 randomly selected clones (400-700 bp each) [35]. For libraries with m > 2, select clones from early to middle PCR rounds to maintain point mutation rates around 2% [36].

Enhanced Cloning via Circular Polymerase Extension Cloning (CPEC)

Materials: epPCR product, linearized vector with 15-20 bp overlaps with insert, high-fidelity DNA polymerase (e.g., TAKARA LA Taq), dNTPs, DpnI restriction enzyme

Procedure:

- Mix epPCR product and linearized vector in 1:3 molar ratio (insert:vector) in 1× PCR buffer with 0.2 mM dNTPs and 1 U high-fidelity polymerase.

Perform CPEC reaction:

- Initial denaturation: 94°C for 2 minutes

- 30 cycles of:

- Denaturation: 94°C for 15 seconds

- Annealing: 63°C for 30 seconds

- Extension: 68°C for 4 minutes (extension time adjusted based on total fragment size)

- Final extension: 72°C for 5 minutes

Digest template plasmid with DpnI (37°C for 1 hour) to eliminate methylated parental DNA.

Transform directly into competent E. coli cells via electroporation (2.5 kV/cm, 25 µF, 200 Ω) [1].

Plate transformed cells on selective media and harvest colonies for library analysis.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Error-Prone PCR Library Construction

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function & Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Polymerases for epPCR | GeneMorph II Random Mutagenesis Kit, Taq DNA polymerase with adjusted buffer | Low-fidelity enzymes for introducing random mutations; commercial kits offer more reproducible mutation spectra |