Benchmark Datasets for Protein Engineering: A 2025 Guide to Evaluation, Application, and Best Practices

This article provides a comprehensive guide to the foundational benchmark datasets powering modern protein engineering.

Benchmark Datasets for Protein Engineering: A 2025 Guide to Evaluation, Application, and Best Practices

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to the foundational benchmark datasets powering modern protein engineering. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores key resources like FLIP, ProteinGLUE, and the Protein Engineering Tournament. The scope covers from foundational knowledge and methodological application to troubleshooting optimization and the comparative validation of computational models, offering a roadmap for rigorous and reproducible protein engineering research.

The Landscape of Protein Engineering Benchmarks: Foundational Datasets and Their Core Tasks

What is Benchmarking and Why Does it Matter?

In protein engineering, benchmarking refers to the use of standardized, community-developed challenges to objectively evaluate and compare the performance of different computational models and AI tools. The primary goal is to measure progress in the field, foster collaboration, and establish transparent standards for what constitutes a reliable method. This process is crucial for transforming protein engineering from a discipline reliant on artisanal, one-off solutions into a reproducible, data-driven science [1] [2].

The need for rigorous benchmarking has become increasingly urgent with the rapid proliferation of machine learning (ML) and artificial intelligence (AI) in biology. Without standardized benchmarks, it is difficult to distinguish genuinely advanced models from those that perform well only on specific, limited datasets. Benchmarks provide a controlled arena where models can be tested on previously unseen data, ensuring that they can generalize their predictions to real-world scenarios. This is exemplified by initiatives like the Protein Engineering Tournament, which is designed as a community-driven challenge to empower researchers to evaluate and improve predictive and generative models, thereby establishing a reference similar to CASP for protein structure prediction [1] [3] [2].

Key Protein Engineering Benchmarking Platforms

Several platforms have emerged as key players in the benchmarking landscape, each with a distinct focus, from general model performance to specific biological problems. The table below summarizes the core features of major contemporary platforms.

Table 1: Comparison of Major Protein Engineering Benchmarking Platforms

| Platform Name | Primary Focus | Key Datasets/Proteins | Evaluation Methodology | Unique Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protein Engineering Tournament [1] [3] [2] | Predictive & generative model performance | PETase (2025), α-Amylase, Aminotransferase, Imine reductase [2] | Predictive: NDCG score; Generative: Free energy change of specific activity [1] | Direct link to high-throughput experimental validation; prizes and recognition. |

| FLIP (Fitness Landscape Inference for Proteins) [4] | Fitness prediction & uncertainty quantification | GB1, AAV, Meltome [4] | Metrics for accuracy, calibration, coverage, and width of uncertainty estimates [4] | Includes tasks with varying domain shifts to test model robustness. |

| TadABench-1M [5] | Out-of-distribution (OOD) generalization | Over 1 million TadA enzyme variants [5] | Performance on random vs. temporal splits (Spearman’s Ï) [5] | Large-scale wet-lab data from 31 evolution rounds; stringent OOD test. |

| PROBE [6] | Protein Language Model (PLM) performance | Various for ontology, target family, and interaction prediction [6] | Evaluation on semantic similarity, function prediction, etc. [6] | Framework for evaluating PLMs on function-related tasks. |

| LLPS Benchmark [7] | Liquid-Liquid Phase Separation (LLPS) prediction | Curated driver, client, and negative proteins from multiple databases [7] | Benchmarking against 16 predictive algorithms [7] | Provides high-confidence, categorized datasets for a complex phenomenon. |

Experimental Protocols in Benchmarking

A critical strength of modern benchmarks is their foundation in robust, reproducible experimental protocols. This section details the common workflows and a specific experimental case study.

Common Benchmarking Workflow

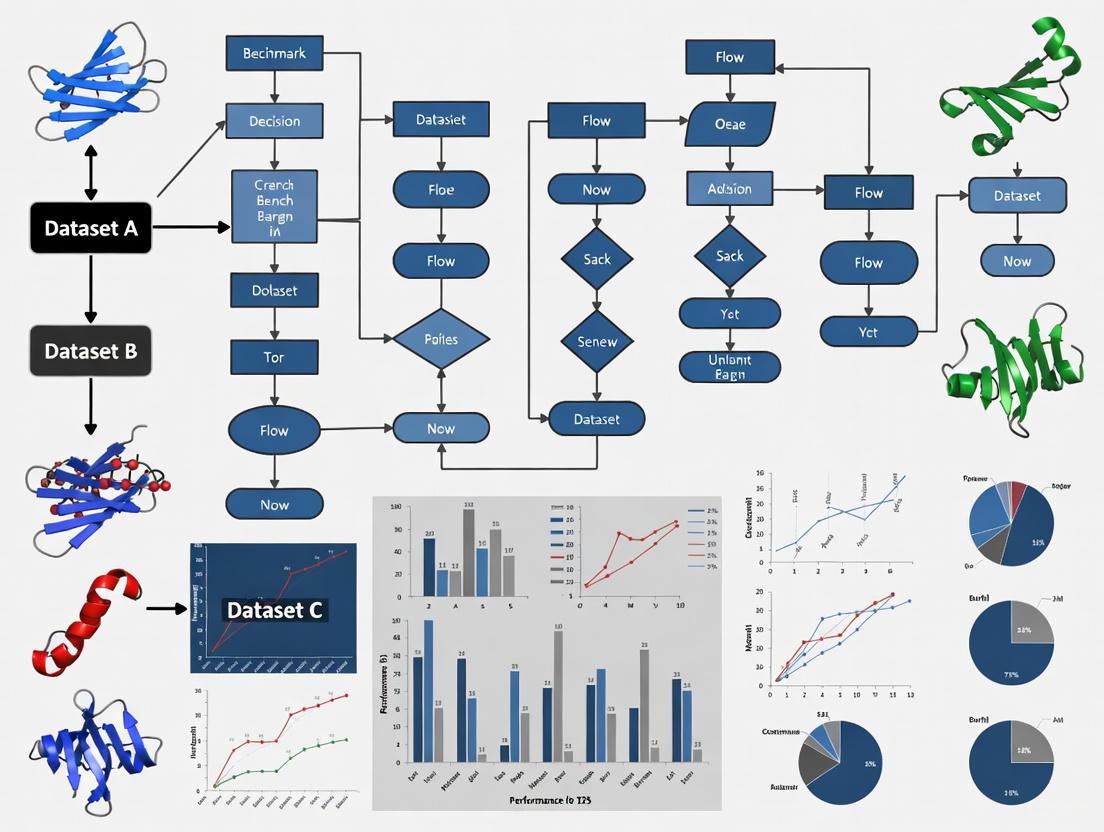

The following diagram illustrates the generalized iterative cycle used by comprehensive benchmarking platforms like the Protein Engineering Tournament.

Diagram 1: The iterative cycle used by comprehensive benchmarking platforms like the Protein Engineering Tournament. This workflow closes the loop between computation and experiment, creating a feedback mechanism for continuous model improvement [1] [3] [2].

Case Study: The 2025 PETase Tournament Protocol

The 2025 PETase Tournament provides a clear example of a two-phase benchmarking protocol designed to rigorously test models [1].

Phase 1: Predictive Round

- Objective: Teams predict biophysical properties (e.g., activity, thermostability, expression) from given protein sequences.

- Tracks: The round is divided into two tracks to test different model capabilities. The Zero-Shot Track requires predictions without any training data, testing the model's intrinsic robustness. The Supervised Track provides a training dataset of measured properties for model development before prediction on a hidden test set [1] [2].

- Evaluation: Submissions are ranked using Normalized Discounted Cumulative Gain (NDCG), which measures how well a model's prediction rankings correlate with the ground-truth experimental rankings [1].

Phase 2: Generative Round

- Objective: Teams design novel protein sequences that optimize desired traits, such as high enzyme activity while maintaining stability.

- Procedure: Top teams from the predictive phase are invited to submit their designed sequences. These sequences are then synthesized (e.g., by Twist Bioscience), expressed, and characterized experimentally in the lab to measure their actual performance [1].

- Evaluation: Designs are ranked based on the free energy change of specific activity relative to a benchmark value. The overall winner is determined by the average improvement across the top 10% of sequences [1].

Quantitative Evaluation Metrics

The performance of models in these benchmarks is quantified using a suite of metrics that go beyond simple prediction accuracy.

Table 2: Key Metrics for Evaluating Predictive Models in Protein Engineering

| Metric Category | Specific Metric | What It Measures | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Predictive Accuracy | Normalized Discounted Cumulative Gain (NDCG) [1] | Quality of a prediction ranking against the true ranking. | Higher is better. Essential for tasks where the rank order of variants is critical. |

| Uncertainty Quantification | Miscalibration Area (AUCE) [4] | Difference between a model's predicted confidence intervals and its actual accuracy. | Lower is better. A well-calibrated model's 95% confidence interval contains the true value ~95% of the time. |

| Uncertainty Quantification | Coverage vs. Width [4] | Percentage of true values within the confidence interval (coverage) vs. the size of that interval (width). | Ideal model has high coverage (≥95%) with low width (precise estimates). |

| Generative Performance | Free Energy Change (ΔΔG) [1] | Improvement in specific activity of a designed enzyme relative to a benchmark. | Lower (more negative) ΔΔG indicates a more active designed enzyme. |

| Correlation | Spearman's Rank Correlation (Ï) [5] | How well the model's predictions monotonically correlate with true values. | Ï â‰ˆ 1.0 is perfect; Ï â‰ˆ 0.1 indicates failure, especially on OOD tasks [5]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Materials

Successful participation in protein engineering benchmarks relies on a suite of computational and experimental tools.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions for Protein Engineering Benchmarks

| Tool / Reagent | Function / Purpose | Example Use in Benchmarking |

|---|---|---|

| High-Throughput DNA Synthesizers | Rapid, automated generation of genetic variants for testing. | Used by tournament sponsors (e.g., Twist Bioscience) to synthesize designed sequences for experimental validation [1] [8]. |

| Automated Laboratory Robots | Handle liquid transfers and assays at scale, ensuring reproducibility. | Enable high-throughput experimental characterization of thousands of protein variants [8] [2]. |

| Protein Language Models (PLMs) | Deep learning models that learn representations from protein sequences. | Used as a foundational representation for prediction tasks in benchmarks like PROBE and FLIP [4] [6]. |

| Structured Data Models (Pydantic) | Standardize and validate data for ML pipelines, enhancing reproducibility. | Helps package predictive methods for large-scale benchmarking, ensuring data interoperability [9]. |

| Multi-Objective Datasets | Contain measurements for multiple properties (activity, stability, expression). | Form the core of tournament events, allowing for the evaluation of multi-property optimization [2]. |

| 7-(4-Bromobutoxy)chromane | 7-(4-Bromobutoxy)chromane, MF:C13H17BrO2, MW:285.18 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Furyltrimethylenglykol | Furyltrimethylenglykol|1-(2-Furyl)ethane-1,2-diol | Furyltrimethylenglykol (1-(2-Furyl)ethane-1,2-diol), CAS 19377-75-4. A furan-based glycol for research. This product is For Research Use Only (RUO). Not for human or animal consumption. |

Critical Challenges and Future Outlook

Despite significant progress, the field of benchmarking in protein engineering still faces several challenges. A major finding from recent research is that uncertainty quantification (UQ) methods are highly context-dependent; no single UQ technique consistently outperforms others across all protein datasets and types of distributional shift [4]. Furthermore, models that excel on standard random data splits can fail dramatically (e.g., Spearman's Ï dropping from 0.8 to 0.1) when faced with realistic out-of-distribution (OOD) generalization tasks, such as predicting the properties of future evolutionary rounds [5]. The creation of high-quality negative datasets (proteins confirmed not to have a property) also remains a significant hurdle for tasks like predicting liquid-liquid phase separation [7].

The future of benchmarking will likely involve more complex, multi-property optimization challenges that better reflect real-world engineering goals. Platforms like the Protein Engineering Tournament are evolving into recurring events (every 18-24 months) with new targets, creating a longitudinal measure of progress for the community [3]. The integration of ever-larger wet-lab validated datasets, such as TadABench-1M, will continue to push the boundaries of model robustness and generalizability, ultimately accelerating the design of novel proteins for therapeutic and environmental applications [5].

The field of computational protein engineering has witnessed remarkable growth, driven by the potential of machine learning (ML) to accelerate the design of proteins for therapeutic and industrial applications. Central to this progress is the development of benchmarks that standardize the evaluation of ML models, enabling researchers to measure collective progress and compare methodologies transparently. The Fitness Landscape Inference for Proteins (FLIP) benchmark emerges as a critical framework designed specifically to assess how well models capture the sequence-function relationships essential for protein engineering [10] [11]. Unlike existing benchmarks such as CASP (for structure prediction) or CAFA (for function prediction), FLIP specifically targets metrics and generalization scenarios relevant for engineering applications, including low-resource data settings and extrapolation beyond training distributions [10].

This guide provides a comparative analysis of FLIP against other prominent benchmarking platforms, detailing its experimental composition, performance data, and practical implementation. We situate FLIP within a broader thesis on protein engineering benchmarks, which posits that the careful design of tasks, data splits, and evaluation metrics is fundamental to driving the methodological innovations needed to solve complex biological design problems.

FLIP Benchmark: Core Design and Datasets

Objectives and Structure

FLIP is conceived as a benchmark for function prediction to encourage rapid scoring of representation learning for protein engineering [10] [11]. Its primary objective is to probe model generalization in settings that mirror real-world protein engineering challenges. To this end, its curated train-validation-test splits, baseline models, and evaluation metrics are designed to simulate critical scenarios such as working with limited data (low-resource) and making predictions for sequences that are structurally or evolutionarily distant from those seen during training (extrapolative) [10] [12].

Datasets and Key Characteristics

FLIP encompasses experimental data from several protein systems, each chosen for its biological and engineering relevance. The benchmark is structured for ease of use and future expansion, with all data presented in a standard format [10]. The core datasets included in FLIP are summarized below.

Table: Core Datasets within the FLIP Benchmark

| Dataset | Biological Function | Engineering Relevance | Key Measured Properties |

|---|---|---|---|

| GB1 | Immunoglobulin-binding protein B1 domain [13] [4] | Affinity and stability engineering [10] | Protein stability and immunoglobulin binding [10] [11] |

| AAV | Adeno-associated virus [13] [4] | Gene therapy vector development [10] | Viral capsid stability [10] [11] |

| Meltome | Various protein families [13] [4] | Thermostability enhancement | Protein thermostability [10] [11] |

The Competitive Landscape: FLIP vs. Other Benchmarks

FLIP operates within a growing ecosystem of protein benchmarks. Understanding its position relative to other initiatives is crucial for researchers selecting the most appropriate platform for their goals.

Table: Comparison of Protein Engineering Benchmarks

| Benchmark | Primary Focus | Key Features | Experimental Validation |

|---|---|---|---|

| FLIP [10] [11] | Fitness landscape inference for proteins | Curated splits for low-resource and extrapolative generalization; standard format. | Retrospective analysis of existing experimental data. |

| Protein Engineering Tournament [3] [2] | Predictive and generative model benchmarking | Fully-remote competition with predictive and generative rounds; iterative with new targets. | Direct, high-throughput experimental characterization of submitted designs. |

| TAPE [12] | Protein representation learning | Set of five semi-supervised tasks across different protein biology domains. | Retrospective analysis of existing data. |

| ProteinGym [14] | Protein language model and ML benchmarking | Aggregation of massive-scale deep mutational scanning (DMS) data; standardized benchmarks. | Retrospective analysis of existing DMS data. |

The Protein Engineering Tournament represents a complementary, competition-based approach. It creates tight feedback loops between computation and experiment by having participants first predict protein properties and then design new sequences, which are synthesized and tested in the lab by tournament partners [3] [2]. This model is particularly powerful for benchmarking generative design tasks, where the ultimate goal is to produce novel, functional sequences.

In contrast, FLIP is predominantly focused on predictive modeling of fitness from sequence. Its strength lies in its carefully designed data splits that test generalization under realistic data collection scenarios, making it an essential tool for developing robust sequence-function models [10] [4].

Performance Comparison and Experimental Data

Insights from Uncertainty Quantification Benchmarking

A 2025 study by Greenman et al. provides critical experimental data comparing model performance on FLIP tasks, specifically benchmarking Uncertainty Quantification (UQ) methods [13] [4]. This work implemented a panel of UQ methods—including Bayesian ridge regression, Gaussian processes, and several convolutional neural network (CNN) variants (ensemble, dropout, evidential)—on regression tasks from FLIP [4].

The study utilized three FLIP landscapes (GB1, AAV, Meltome) and selected eight tasks representing varying degrees of domain shift, from random splits (no shift) to more challenging extrapolative splits like "AAV/Random vs. Designed" and "GB1/1 vs. Rest" [4]. Key findings from this benchmarking are summarized below.

Table: Key Findings from UQ Benchmarking on FLIP Tasks

| Aspect Evaluated | Key Result | Implication for Protein Engineering |

|---|---|---|

| Overall UQ Performance | No single UQ method consistently outperformed all others across datasets, splits, and metrics [4]. | Method selection is context-dependent; benchmarking on specific landscapes of interest is crucial. |

| Model Calibration | Miscalibration (the difference between predicted confidence and empirical accuracy) was observed, particularly on out-of-domain samples [4]. | Poor calibration can misguide experimental design; robust UQ is needed for reliable active learning. |

| Sequence Representation | Performance and calibration were compared using one-hot encodings and embeddings from the ESM-1b protein language model [4]. | Pretrained language model representations can enhance model performance and uncertainty estimation. |

| Bayesian Optimization | Uncertainty-based sampling for optimization often failed to outperform simpler greedy sampling strategies [13] [4]. | Challenged the default assumption that sophisticated UQ always improves sequence optimization. |

Detailed Experimental Protocol

The UQ benchmarking study offers a reproducible template for evaluating models on FLIP. The core methodology can be broken down into the following steps [4]:

- Task and Split Selection: Researchers select relevant tasks from the FLIP benchmark (e.g., GB1/1 vs. Rest for a high domain-shift scenario).

- Model and UQ Method Implementation: A suite of models (e.g., CNN ensembles, Gaussian processes) is implemented. Each is configured to output both a predicted fitness value and an associated uncertainty estimate.

- Sequence Representation: Protein sequences are converted into feature representations, typically either one-hot encodings or embeddings from a pretrained protein language model like ESM-1b [4].

- Training and Evaluation: Models are trained on the training split of the chosen task. Predictions and uncertainties are generated for the held-out test set.

- Metric Calculation: Performance is assessed using a battery of metrics evaluating:

- Accuracy: How close predictions are to true values (e.g., RMSE).

- Calibration: How well the predicted confidence intervals match the observed error (e.g., Miscalibration Area/AUCE) [4].

- Coverage and Width: The proportion of true values falling within the confidence interval and the size of that interval [4].

- Downstream Application Simulation: The UQ methods are further tested in retrospective active learning and Bayesian optimization loops to assess their practical utility in guiding experimental design.

The workflow for this protocol is visualized in the following diagram.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Implementing and benchmarking models on FLIP requires a suite of computational tools and resources. The following table details key "research reagent" solutions for this field.

Table: Essential Research Reagents for Protein Fitness Benchmarking

| Tool / Resource | Type | Primary Function | Relevance to FLIP |

|---|---|---|---|

| FLIP Datasets [10] | Benchmark Data | Provides standardized datasets and splits for evaluating sequence-function models. | The core data source; includes GB1, AAV, and Meltome landscapes. |

| ESM-2 Model [14] | Protein Language Model | Generates contextual embeddings from protein sequences using a transformer architecture. | Used as a powerful feature representation for input sequences, replacing one-hot encoding [4]. |

| Ridge Regression [14] | Machine Learning Model | A regularized linear model used for regression tasks. | Serves as a strong, interpretable baseline model for fitness prediction [14]. |

| CNN Architectures [4] | Deep Learning Model | A flexible neural network architecture for processing sequence data. | The core architecture for many advanced UQ methods (ensembles, dropout, etc.) in FLIP benchmarks [4]. |

| Uncertainty Methods (Ensemble, Dropout, Evidential) [4] | Algorithmic Toolkit | Provides estimates of prediction uncertainty in addition to the mean prediction. | Critical for enabling Bayesian optimization and active learning in protein engineering [13] [4]. |

| Tribenzyl Miglustat | Tribenzyl Miglustat, MF:C31H39NO4, MW:489.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| 2-(chloromethyl)Butanal | 2-(chloromethyl)Butanal|C5H9ClO|Research Chemical | 2-(chloromethyl)Butanal is a chlorinated aldehyde for research use only (RUO). It serves as a versatile synthetic intermediate in organic chemistry. | Bench Chemicals |

FLIP establishes a vital, publicly accessible foundation for benchmarking predictive models in protein engineering. Its rigorously designed tasks probe model generalization in regimes that matter for practical applications, filling a gap left by structure- or function-focused benchmarks. Experimental data from studies like the 2025 UQ benchmark reveal that while FLIP enables rigorous model comparison, it also highlights that no single method is universally superior. The performance of UQ techniques and sequence representations is highly dependent on the specific dataset and the nature of the distribution shift, underscoring the need for continued innovation and careful model selection.

The future of protein engineering benchmarking is moving towards an integrated ecosystem where predictive benchmarks like FLIP, TAPE, and ProteinGym coexist with generative, experimentally-validated competitions like the Protein Engineering Tournament [3] [2]. This dual approach ensures that progress in accurately predicting fitness from sequence is continuously validated by the ultimate test: the successful design of novel, functional proteins in the lab. As the field advances, FLIP's standardized and extensible format positions it to incorporate new datasets and challenges, ensuring its continued role in propelling the development of more powerful and reliable machine learning tools for protein engineering.

Contents

- Introduction

- The ProteinGLUE Benchmark Suite

- Comparative Analysis of Protein Benchmarks

- ProteinGLUE Experimental Framework

- Research Reagent Solutions

In the field of protein engineering, the rapid development of self-supervised learning models for protein sequence data has created a pressing need for standardized evaluation tools. Work in this area is heterogeneous, with models often assessed on only one or two downstream tasks, making it difficult to determine whether they capture generally useful biological properties [15]. To address this challenge, ProteinGLUE was introduced as a multi-task benchmark suite specifically designed for the evaluation of self-supervised protein representations [15] [16]. It provides a set of standardized downstream tasks, reference code, and baseline models to facilitate fair and comprehensive comparisons across different protein modeling approaches [15]. This guide objectively compares ProteinGLUE's performance and design with other benchmark suites, situating it within the broader ecosystem of protein engineering research.

The ProteinGLUE Benchmark Suite

ProteinGLUE is comprised of seven per-amino-acid classification and regression tasks that probe different structural and functional properties of proteins [15]. These tasks were selected because they provide a high density of labels (one per residue) and are closely linked to protein function [15].

Table 1: Downstream Tasks in the ProteinGLUE Benchmark

| Task Name | Prediction Type | Biological Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Secondary Structure | Classification (3 or 8 classes) | Describes local protein structure patterns (α-helix, β-strand, coil) [15]. |

| Solvent Accessibility | Regression & Classification | Indicates surface area of an amino acid accessible to solvent; key for understanding surface exposure [15]. |

| Protein-Protein Interaction (PPI) Interface | Classification | Identifies residues involved in interactions between proteins; crucial for understanding cellular processes [15] [17]. |

| Epitope Region | Classification | Predicts the antigen region recognized by an antibody; a specific type of PPI [15]. |

| Hydrophobic Patch Prediction | Regression | Identifies adjacent surface hydrophobic residues important for protein aggregation and interaction [15]. |

The benchmark provides two pre-trained baseline models—a Medium model (42 million parameters) and a Base model (110 million parameters)—which are based on the BERT transformer architecture and pre-trained on protein sequences from the Pfam database [15]. The core finding from the initial ProteinGLUE study was that self-supervised pre-training on unlabeled sequence data yielded higher performance on these downstream tasks compared to no pre-training [15].

Comparative Analysis of Protein Benchmarks

Several benchmark suites have been developed to evaluate protein models, each with a distinct focus. The table below provides a comparative overview of ProteinGLUE and its contemporaries.

Table 2: Comparison of Protein Modeling Benchmarks

| Benchmark | Primary Focus | Key Tasks | Model Types Evaluated | Notable Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ProteinGLUE [15] [17] | Quality of general protein representations | Secondary structure, Solvent accessibility, PPI, Epitopes [15]. | Primarily sequence-based models (e.g., Transformer) [15]. | Seven per-amino-acid tasks; provides two baseline BERT models [15]. |

| TAPE [17] [18] | Assessing protein embeddings | Secondary structure, Remote homology, Fluorescence, Stability [18]. | Sequence-based models [17]. | One of the earliest benchmarks; five sequence-centric tasks [17] [18]. |

| PEER [17] [18] | Multi-task learning & representations | Protein property, Localization, Structure, PPI, Protein-ligand interactions [18]. | Not specified in search results. | Richer set of evaluations; investigates multi-task learning setting [18]. |

| ProteinGym [18] | Fitness prediction & design | Deep Mutational Scanning (DMS), Clinical variant effects [18]. | Alignment-based, inverse folding, language models [18]. | Large-scale (250+ assays); focuses on a single, critical task (fitness) [18]. |

| Protap [17] | Realistic downstream applications | Protein-ligand interactions, Function, Mutation, Enzyme cleavage, Targeted degradation [17]. | Language models, Geometric GNNs, Sequence-structure hybrids, Domain-specific [17]. | Systematically compares general and domain-specific models; introduces novel specialized tasks [17]. |

| ProteinWorkshop [17] | Structure-based models | Not specified in detail. | Equivariant Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) [17]. | Focuses on evaluating models that leverage 3D structural data [17]. |

A key differentiator for ProteinGLUE is its exclusive focus on per-amino-acid tasks, which contrasts with benchmarks like ProteinGym that specialize in protein-level fitness prediction [18] or Protap that covers a wider variety of task types, including interactions and specialized applications [17]. Furthermore, while later benchmarks like Protap and ProteinWorkshop have expanded to include structure-based models, ProteinGLUE, akin to TAPE, primarily centers on evaluating sequence-based models [17].

ProteinGLUE Experimental Framework

Pre-training Methodology

The baseline models for ProteinGLUE were pre-trained using a self-supervised approach on a large corpus of unlabeled protein sequences from the Pfam database [15]. The training incorporated two objectives adapted from natural language processing:

- Masked Symbol Prediction: Random amino acids in a sequence are masked (hidden), and the model must predict the missing tokens based on the surrounding context [15].

- Next Sentence Prediction: The model is trained to determine if one protein sequence logically follows another, although the applicability of this objective for proteins is noted as an area for future investigation [15].

The model architectures are transformer-based, specifically patterned after BERT (Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers) [15].

Table 3: ProteinGLUE Baseline Model Architectures

| Model | Hidden Layers | Attention Heads | Hidden Size | Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medium | 8 | 8 | 512 | 42 million |

| Base | 12 | 12 | 768 | 110 million |

Fine-tuning and Evaluation Protocol

For downstream task evaluation, the pre-trained models are adapted through a fine-tuning process:

- Procedure: The pre-trained model is used as a starting point and is further trained (fine-tuned) on the labeled data of each specific downstream task (e.g., secondary structure prediction). This allows the general knowledge learned from Pfam to be specialized for the target task [15].

- Performance: Experiments demonstrated that pre-training consistently yields higher performance on the downstream tasks compared to training from scratch without pre-training. Interestingly, the larger Base model did not outperform the smaller Medium model, suggesting that model size alone is not a guarantee of better performance on these tasks [15].

The following diagram illustrates the end-to-end workflow for training and evaluating a model on the ProteinGLUE benchmark.

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key resources provided by the ProteinGLUE benchmark, which are essential for replicating experiments and advancing research in this field.

Table 4: Key Research Reagents for ProteinGLUE Benchmarking

| Resource | Type | Description | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| ProteinGLUE Datasets | Benchmark Data | Standardized datasets for seven per-amino-acid prediction tasks [15]. | Provides ground-truth labels for training and fairly evaluating model performance on diverse protein properties. |

| Pfam Database | Pre-training Data | A widely used database of protein families and sequences [15]. | Serves as the large, unlabeled corpus for self-supervised pre-training of protein language models. |

| BERT-Medium Model | Pre-trained Model | A transformer model with 42 million parameters [15]. | Acts as a baseline for comparison; a smaller model that can overcome computational limits. |

| BERT-Base Model | Pre-trained Model | A transformer model with 110 million parameters [15]. | Serves as a larger baseline model to assess the impact of model scale on performance. |

| Reference Code | Software | Open-source code for model pre-training, fine-tuning, and evaluation [15]. | Ensures reproducibility and allows researchers to build upon established methods. |

The Protein Engineering Tournament is a biennial, open-science competition established to address critical bottlenecks in computational protein engineering: the lack of standardized benchmarks, large functional datasets, and accessible experimental validation [2] [19]. Orchestrated by The Align Foundation, the tournament creates a transparent platform for benchmarking computational methods that predict protein function and design novel protein sequences [3]. By connecting computational predictions directly with high-throughput experimental validation, the tournament generates rigorous, publicly available benchmarks that allow the research community to evaluate progress, understand what methods work, and identify areas needing improvement [3].

This initiative fills a crucial gap in the field. While predictive and generative models for protein engineering have advanced significantly, their development has been hampered by limited benchmarking opportunities, a scarcity of large and complex protein function datasets, and most computational scientists' lack of access to experimental characterization resources [2] [20]. The Tournament is designed to overcome these obstacles by providing a shared arena where diverse research groups can test their methods against unseen data and have their designed sequences synthesized and tested in the lab, regardless of their institutional resources [2] [19].

The Tournament's structure is modeled after historically successful benchmarking efforts that have propelled entire fields forward. It draws inspiration from competitions like the Critical Assessment of Structure Prediction (CASP) for protein structure prediction, the DARPA Grand Challenges for autonomous vehicles, and ImageNet for computer vision [3] [21]. These platforms demonstrated that carefully designed benchmarks, paired with high-quality data, can consistently catalyze transformative scientific breakthroughs by building communities around shared goals [3].

Tournament Structure and Comparative Framework

Comparative Analysis with Other Benchmarking Platforms

The Protein Engineering Tournament distinguishes itself from existing benchmarks through its unique integration of predictive and generative tasks coupled with experimental validation. Table 1 provides a systematic comparison of the Tournament against other major platforms in computational biology.

Table 1: Comparison of Protein Engineering Tournament with Other Benchmarking Platforms

| Platform Name | Primary Focus | Experimental Validation | Data Availability | Participation Scope | Key Limitations Addressed |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protein Engineering Tournament [3] [2] | Protein function prediction & generative design | Integrated DNA synthesis & wet lab testing | All datasets & results made public | Global; academia, industry, independents | Bridges computation-experimentation gap |

| CASP (Critical Assessment of Structure Prediction) [3] [20] | Protein structure prediction | Limited to experimental structure comparison | Predictions & targets public | Primarily academic research | Inspired Tournament framework |

| CACHE (Critical Assessment of Computational Hit-finding) [2] | Small molecule binders | Varies by challenge | Limited public data | Computational chemistry community | Focuses on small molecules, not proteins |

| FLIP [2] | Fitness landscape inference | No integrated validation | Public benchmark datasets | Computational biology | Limited to predictive modeling |

| TAPE [2] | Protein sequence analysis | No integrated validation | Public benchmark tasks | Machine learning research | Excludes generative design |

| ProteinGym [2] | Fitness prediction | No integrated validation | Curated mutational scans | Computational biology | Focused on single point mutations |

As evidenced in Table 1, the Tournament fills a unique niche by addressing the complete protein engineering pipeline—from prediction to physical design and experimental validation. Unlike benchmarks focused solely on predictive modeling (FLIP, TAPE) or those limited to structure prediction (CASP), the Tournament specifically tackles the challenge of engineering protein function, which requires testing under real-world conditions [2]. This end-to-end approach is crucial because computational models can produce designs that appear optimal in silico but fail to function as intended when synthesized and tested experimentally.

Two-Phase Tournament Architecture

The Tournament operates through two sequential phases that mirror the complete protein engineering workflow, creating what the organizers describe as a "tight feedback loop between computation and experiments" [3].

Predictive Phase: In this initial phase, participants develop computational models to predict biophysical properties—such as enzymatic activity, thermostability, and expression levels—from provided protein sequences [2]. This phase operates through two parallel tracks:

- Zero-shot track: Challenges participants to make predictions without any prior training data, testing the intrinsic robustness and generalizability of their algorithms [2].

- Supervised track: Provides pre-split training and test datasets, allowing participants to train their models on sequences with known properties before predicting withheld properties [2].

Teams are ranked using Normalized Discounted Cumulative Gain (NDCG), which measures how well submitted prediction rankings correlate with ground-truth experimental rankings [1]. The evaluation averages NDCG scores across all target protein properties to determine final rankings [1].

Generative Phase: Top-performing teams from the predictive phase advance to design novel protein sequences with optimized traits [3] [1]. In this phase, participants submit sequences designed to maximize or satisfy specific functional criteria. The Tournament then synthesizes these designs—free of charge to participants—and tests them in vitro using standardized experimental protocols [1] [2]. Designs are ranked based on experimental performance metrics, primarily the free energy change of specific activity relative to benchmark values while maintaining threshold expression levels [1].

The following workflow diagram illustrates this iterative two-phase structure:

Diagram 1: Protein Engineering Tournament Workflow. The tournament operates through sequential predictive and generative phases, with experimental validation bridging both stages.

The 2025 PETase Tournament: A Case Study in Real-World Impact

Tournament Objectives and Societal Significance

The 2025 iteration of the Protein Engineering Tournament focuses on engineering polyethylene terephthalate hydrolase (PETase), an enzyme that degrades PET plastic [1] [21]. This target selection demonstrates the Tournament's commitment to addressing societally significant problems that may lack sufficient economic incentives for industry or academia to tackle individually [20]. The plastic waste crisis represents a monumental global challenge—with plastic waste projected to triple by 2060 and less than 10% currently being recycled [21]. PETase offers a potential biological solution by breaking down PET into reusable monomers that can be made into new, high-quality plastic, enabling true circular recycling rather than the downgrading that characterizes traditional recycling methods [21].

Despite over a decade of research, engineering PETase for industrial application has faced persistent hurdles. The enzyme must remain active at high temperatures, tolerate pH swings, and act on solid plastic substrates—challenges that have stalled progress even as plastic pollution inflicts enormous economic damage estimated at $1.5 trillion annually in health-related economic losses alone [21]. The Tournament addresses these challenges by crowdsourcing innovation from diverse global teams and validating designed enzyme variants under real-world conditions [21].

Experimental Methodology and Evaluation Criteria

The 2025 PETase Tournament implements rigorous experimental protocols to ensure fair and meaningful comparison of computational methods. The evaluation framework spans both tournament phases with distinct metrics for each stage:

Table 2: 2025 PETase Tournament Experimental Framework

| Phase | Input Provided | Team Submission | Experimental Validation | Evaluation Metrics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictive Phase [1] [2] | Protein sequences for prediction; Training data (supervised track) | Property predictions: activity, thermostability, expression | Comparison against ground-truth experimental data | Normalized Discounted Cumulative Gain (NDCG) |

| Generative Phase [1] | Training dataset of natural PETase sequences and variants | Ranked list of up to 200 designed amino acid sequences | DNA synthesis, protein expression, and functional assays | Free energy change of specific activity relative to benchmark |

The experimental characterization measures multiple biophysical properties critical for real-world enzyme functionality:

- Enzymatic activity: Quantified under standardized conditions to assess plastic degradation efficiency [22]

- Thermostability: Measured to ensure enzyme function at elevated temperatures relevant to industrial processes [1]

- Expression levels: Evaluated to determine practical feasibility and production costs [1] [2]

For the generative phase, the primary ranking criterion is the free energy change of specific activity relative to benchmark values, reflecting the catalytic efficiency improvement of designed variants [1]. Additionally, sequences must maintain threshold expression levels, ensuring that improvements in activity aren't offset by poor protein production [1].

Analysis of Pilot Tournament Outcomes and Methodological Insights

Pilot Tournament Implementation and Participation

The 2023 Pilot Tournament served as a proof-of-concept, validating the Tournament's structure and generating valuable initial benchmarks [2]. It attracted substantial community interest, with over 90 individuals registering across 28 teams representing academic (55%), industry (30%), and independent (15%) participants [2]. This diverse participation demonstrates the Tournament's success in engaging the broader protein engineering community across institutional boundaries.

The Pilot featured six multi-objective datasets donated by academic and industry partners, focusing on various enzyme targets including α-Amylase, Aminotransferase, Imine Reductase, Alkaline Phosphatase PafA, β-Glucosidase B, and Xylanase [2]. These datasets represented a range of engineering challenges and protein functions, from catalytic activity against different substrates to expression and thermostability optimization [2]. Of the initial 28 registered teams, seven successfully submitted predictions for the predictive round, with five teams advancing from the predictive round joined by two additional generative-method teams in the generative round [2].

Performance Results and Methodological Evaluation

The Pilot Tournament generated quantitative benchmarks for comparing protein engineering methods across different functional prediction tasks. Table 3 summarizes the key outcomes from the predictive phase across different challenge problems.

Table 3: Pilot Tournament Predictive Phase Outcomes and Performance Metrics

| Enzyme Target | Dataset Properties | Prediction Track | Top Performing Teams | Key Performance Insights |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aminotransferase [2] | Activity against 3 substrates | Zero-shot | Marks Lab | Multi-substrate activity prediction remains challenging |

| α-Amylase [2] | Expression, specific activity, thermostability | Zero-shot & Supervised | Marks Lab (Zero-shot), Exazyme & Nimbus (Supervised) | Large dataset enabled effective supervised learning |

| Imine Reductase [2] | Activity (FIOP) | Supervised | Exazyme & Nimbus | High-quality activity prediction achievable with sufficient data |

| Alkaline Phosphatase PafA [2] | Activity against 3 substrates | Supervised | Exazyme & Nimbus | Method performance varies by substrate type |

| β-Glucosidase B [2] | Activity, melting point | Supervised | Exazyme & Nimbus | Stability prediction remains particularly challenging |

| Xylanase [2] | Expression | Zero-shot | Marks Lab | Expression prediction from sequence alone is feasible |

The results revealed several important patterns in methodological performance. The Marks Lab dominated the zero-shot track, suggesting their methods possess strong generalizability without requiring specialized training data [2]. In contrast, Exazyme and Nimbus shared top honors in the supervised track, indicating their approaches effectively leverage available training data [2]. This performance divergence highlights how different computational strategies may excel under different information constraints—a crucial insight for method selection in real-world protein engineering projects where training data availability varies substantially.

The generative phase of the Pilot, though involving fewer teams, demonstrated the Tournament's capacity to bridge computational design with experimental validation. Partnering with International Flavors and Fragrances (IFF), the Tournament experimentally characterized designed protein sequences, providing crucial ground-truth data for evaluating generative methodologies [2]. This experimental validation is particularly valuable because it moves beyond purely in silico metrics to assess actual functional performance—the ultimate measure of success in protein engineering.

The Protein Engineering Tournament provides participants with a comprehensive suite of experimental and computational resources that democratize access to cutting-edge protein engineering capabilities. These resources eliminate traditional barriers to entry, allowing teams to compete based on methodological innovation rather than institutional resources. Table 4 details the key research reagent solutions available to tournament participants.

Table 4: Research Reagent Solutions for Tournament Participants

| Resource Category | Specific Solution | Provider | Function in Protein Engineering Pipeline |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA Synthesis [1] [21] | Gene fragments and variant libraries | Twist Bioscience | Bridges digital designs with biological reality; enables physical testing of computational designs |

| AI Models [21] | State-of-the-art protein language models | EvolutionaryScale | Provides foundational models for feature extraction and sequence design |

| Computational Infrastructure [21] | Scalable compute platform | Modal Labs | Enables intensive computational testing without hardware limitations |

| Experimental Validation [1] [2] | High-throughput characterization | Tournament Partners (e.g., IFF) | Delivers standardized functional data for model benchmarking |

| Training Data [1] [2] | Curated datasets with experimental measurements | Tournament Donors | Supports supervised learning and model training |

| Benchmarking Framework [3] [2] | Standardized evaluation metrics | Align Foundation | Enables fair comparison across diverse methodological approaches |

This infrastructure support represents a crucial innovation in protein engineering research. By providing end-to-end resources—from computational tools to physical DNA synthesis and experimental characterization—the Tournament enables researchers who might otherwise lack wet lab capabilities to participate fully in protein design and validation [21]. This democratization accelerates innovation by expanding the pool of contributors beyond traditional well-resourced institutions.

The partnership with Twist Bioscience is particularly significant, as synthetic DNA provides the critical link between digital sequence designs and their biological realization [21]. Similarly, the provision of computational resources by Modal Labs and AI models by EvolutionaryScale ensures that participants can focus on methodological development rather than computational constraints [21]. This comprehensive support structure exemplifies how thoughtfully designed benchmarking platforms can level the playing field and foster inclusive scientific innovation.

Implications for Protein Engineering Benchmark Research

The Protein Engineering Tournament establishes a transformative framework for benchmarking progress in computational protein engineering. By creating standardized evaluation protocols tied to real experimental outcomes, it addresses a critical deficiency in the field: the lack of transparent, reproducible benchmarks for assessing protein function prediction and design methodologies [2] [19]. This represents a significant advancement beyond existing benchmarks that focus primarily on predictive modeling without connecting to generative design or experimental validation.

The Tournament's impact extends beyond immediate competition outcomes through its commitment to open science. All datasets, experimental protocols, and methods are made publicly available upon tournament completion, creating a growing resource for the broader research community [2] [19]. This open-data approach accelerates methodological progress by providing standardized test sets for developing new algorithms, similar to how ImageNet and MNIST transformed computer vision and machine learning research [2]. The accumulation of high-quality, experimentally verified protein function data through successive tournaments addresses the "data scarcity" problem that has long hampered computational protein engineering [2] [20].

For researchers and drug development professionals, the Tournament offers several valuable resources:

- Standardized benchmarks for comparing methodological approaches against state-of-the-art techniques

- High-quality datasets of protein function for training and validating computational models

- Experimental workflows for characterizing designed protein sequences

- Community-defined evaluation metrics that reflect real-world functional requirements

As the field progresses, the Tournament framework provides a mechanism for tracking collective advancement toward the grand challenge of computational protein engineering: developing models that can reliably characterize and generate protein sequences for arbitrary functions [19]. By establishing this clear benchmarking pathway, the Protein Engineering Tournament enables researchers to measure progress, identify the most promising methodological directions, and ultimately accelerate the development of proteins that address pressing societal needs—from plastic waste degradation to therapeutic development and beyond.

In the field of protein engineering, the study of liquid-liquid phase separation (LLPS) has emerged as a fundamental biological process with far-reaching implications for cellular organization and function. LLPS describes the biophysical mechanism through which proteins and nucleic acids form dynamic, membraneless organelles (MLOs) that serve as hubs for critical cellular activities [7] [23]. These biomolecular condensates facilitate essential processes including transcriptional control, cell fate transitions, and stress response, with dysregulation directly linked to neurodegenerative diseases and cancer [23] [24]. The advancement of this field, however, hinges upon the availability of high-quality, specialized benchmark datasets that enable the development and validation of predictive computational models.

The intrinsic context-dependency of LLPS presents unique challenges for dataset curation. A protein may function as a driver (capable of autonomous phase separation) under certain conditions while acting as a client (recruited into existing condensates) in others [7]. This biological complexity, combined with heterogeneous data annotation across resources, has historically hampered the development of reliable machine learning models for predicting LLPS behavior [7] [4]. The establishment of standardized benchmarks with clearly defined negative sets represents a critical step forward, enabling fair comparison of algorithms and more accurate identification of phase-separating proteins across diverse biological contexts [7] [24]. This article comprehensively compares available LLPS datasets, detailing their construction, experimental underpinnings, and applications in protein engineering research.

Comparative Analysis of LLPS Databases and Datasets

Multiple databases have been developed to catalog proteins involved in phase separation, each with distinct curation focuses and annotation schemes. LLPSDB specializes in documenting experimentally verified LLPS proteins with detailed in vitro conditions, including temperature, pH, and ionic strength [25]. PhaSePro focuses specifically on driver proteins with experimental evidence, while DrLLPS and CD-CODE annotate the roles proteins play within condensates (e.g., scaffold, client, regulator) [7]. The heterogeneity among these resources has driven efforts to create integrated datasets that enable more robust computational analysis.

Table 1: Major LLPS Databases and Their Characteristics

| Database | Primary Focus | Key Annotations | Data Source | Notable Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LLPSDB [25] | In vitro LLPS experiments | Protein sequences, experimental conditions | Manually curated from literature | Includes phase diagrams; documents conditions for both phase separation and non-separation |

| PhaSePro [7] | Driver proteins | Proteins forming condensates autonomously | Curated from literature with evidence levels | Focuses on proteins with strong experimental evidence as drivers |

| DrLLPS [7] | Protein roles in condensates | Scaffold, client, regulator classifications | Integrated from multiple sources | Links proteins to specific membraneless organelles and their functions |

| CD-CODE [7] | Condensate composition | Driver and member proteins for MLOs | Systematic curation | Contextualizes proteins within specific condensate environments |

| FuzDB [7] | Fuzzy interactions | Protein regions with fuzzy interactions | Not primarily LLPS-focused | Useful for identifying potential interaction domains relevant to LLPS |

Integrated and Benchmark LLPS Datasets

To address interoperability challenges, recent initiatives have created harmonized datasets. The Confident Protein Datasets for LLPS provides integrated client, driver, and negative datasets through rigorous biocuration [7] [23]. This resource incorporates over 600 positive entries (clients and drivers) and more than 2,000 negative entries, including both disordered and globular proteins without LLPS association [23]. Each protein is annotated with sequence, disorder fraction (from MobiDB), Gene Ontology terms, and role specificity (Client Exclusive-CE, Driver Exclusive-DE, or both-C_D) [23].

The PSPHunter framework introduced several specialized datasets, including MixPS237 and MixPS488 (mixed-species training sets), and hPS167 (human-specific phase-separating proteins) [24]. These resources incorporate both sequence features and functional attributes such as post-translational modification sites, protein-protein interaction network properties, and evolutionary conservation metrics [24]. The PSProteome, derived from PSPHunter predictions, identifies 898 human proteins with high phase separation potential, 747 of which represent novel predictions beyond established databases [24].

Table 2: Key Benchmark Datasets for LLPS Prediction

| Dataset | Protein Count | Species | Key Features | Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Confident LLPS Datasets [23] | >600 positive; >2,000 negative | Multiple | Explicit client/driver distinction; negative sets with disordered proteins | Training and benchmarking LLPS predictors; property analysis |

| PSPHunter (hPS167) [24] | 167 | Human | Integrates sequence & functional features; PSPHunter scores | Predicting human phase-separating proteome; key residue identification |

| PSPHunter (MixPS488) [24] | 488 | Multiple | Mixed-species; diverse features | Cross-species prediction model training |

| PSProteome [24] | 898 | Human | High-confidence predictions (score >0.82) | Proteome-wide screening for LLPS candidates |

| LLPSDB v2.0 [25] | 586 independent proteins | Multiple | 2,917 entries with detailed experimental conditions | Studying condition-dependent LLPS behavior |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Dataset Construction and Curation Protocols

The creation of high-confidence LLPS datasets follows rigorous biocuration protocols. For the Confident Protein Datasets, researchers implemented a multi-stage process: First, they compiled data from major LLPS resources (LLPSDB, PhaSePro, PhaSepDB, CD-CODE, DrLLPS) [7]. Next, they applied standardized filters to ensure consistent evidence levels, distinguishing driver proteins based on autonomous phase separation capability without partner dependencies [7]. For databases with client/driver labels, they required at least in vitro experimental evidence [7]. Finally, they validated category assignments through cross-database checks, identifying exclusive clients (CE), exclusive drivers (DE), and dual-role proteins (C_D) [7].

Negative dataset construction followed equally stringent protocols. The ND (DisProt) and NP (PDB) datasets were built by selecting entries with no LLPS association in source databases, no presence in LLPS resources, and no annotations of potential LLPS interactors [7] [23]. This careful negative set selection is crucial for preventing biases in machine learning models that might otherwise simply distinguish disordered from structured regions rather than genuine LLPS propensity [23].

Experimental Validation Methods for LLPS

The datasets referenced in this review build upon experimental evidence gathered through multiple established techniques:

In Vitro Phase Separation Assays: Purified proteins are observed under specific buffer conditions (varying temperature, pH, salt concentration) to assess droplet formation [25] [24]. This provides direct evidence of LLPS capability.

Fluorescence Recovery After Photobleaching (FRAP): This technique confirms liquid-like properties by measuring the mobility of fluorescently tagged proteins within condensates after photobleaching [24]. Rapid recovery indicates dynamic liquid character rather to solid aggregates.

Immunofluorescence and Labeling: Fluorescent tags (e.g., GFP) visualize protein localization into puncta or condensates within cells, providing in vivo correlation [24].

Condition-Dependent Screening: Systematic variation of parameters (ionic strength, crowding agents, protein concentration) reveals the specific conditions under which phase separation occurs [25]. LLPSDB specifically catalogs these experimental conditions.

The integration of evidence from these multiple methodologies ensures the high-confidence annotations present in the benchmark datasets discussed herein.

Visualization: LLPS Dataset Generation Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow for generating confident LLPS datasets, from initial data collection to final category assignment:

LLPS Dataset Generation Workflow: This diagram outlines the multi-stage process for creating confident LLPS datasets, from initial data collection from source databases through evidence-based filtering, role classification, negative set construction, and final validation. The process emphasizes cross-database checks and incorporation of experimental evidence to ensure data quality.

Table 3: Key Experimental Reagents and Computational Resources for LLPS Research

| Resource/Reagent | Type | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Confident LLPS Datasets [23] | Data Resource | Provides validated client/driver/negative proteins | Benchmarking predictive algorithms; training ML models |

| LLPSDB [25] | Database | Documents specific experimental conditions | Understanding context-dependent LLPS behavior |

| PSPHunter [24] | Tool & Dataset | Predicts phase-separating proteins & key residues | Identifying key residues; proteome-wide screening |

| DisProt [7] | Database | Source of disordered proteins without LLPS association | Negative set construction; avoiding sequence bias |

| MobiDB [23] | Database | Annotates protein disorder regions | Feature annotation in datasets |

| FRAP [24] | Experimental Method | Measures dynamics within condensates | Validating liquid-like properties |

| ESM-1b Embeddings [4] | Computational Tool | Protein language model representations | Feature encoding for ML models |

Discussion and Future Perspectives

The development of specialized benchmarks for LLPS research represents a significant advancement toward reliable predictive modeling in protein engineering. The curated datasets described herein, with their explicit distinction between driver and client proteins and carefully constructed negative sets, address critical limitations in earlier resources [7] [23]. The incorporation of quantitative features such as disorder propensity, evolutionary conservation, and post-translational modification sites enables more nuanced analysis of sequence-determinants of phase separation [24].

These benchmarks have revealed important insights: LLPS proteins exhibit significant differences in physicochemical properties not only from non-LLPS proteins but also among themselves, reflecting their diverse roles in condensate assembly and function [7]. Furthermore, the context-dependent nature of LLPS necessitates careful interpretation of both positive and negative annotations, as a protein's behavior may change under different cellular conditions or in the presence of different binding partners [7] [25].

Future directions for LLPS benchmark development include incorporating temporal and spatial resolution data to capture the dynamic nature of condensates, expanding coverage of condition-dependent behaviors, and integrating multi-component system information to better represent the compositional complexity of natural membraneless organelles [7] [24]. As these resources continue to mature, they will undoubtedly accelerate both our fundamental understanding of phase separation biology and the development of therapeutic strategies targeting LLPS in disease.

Choosing the Right Benchmark for Your Protein Engineering Project Goal

Selecting an appropriate benchmark is a critical first step in protein engineering, as it directly influences the assessment of your computational models and guides future research directions. The right benchmark provides a rigorous, unbiased framework for comparing methods, validating new approaches, and understanding your model's performance on real-world biological tasks. This guide compares the main classes of protein engineering benchmarks to help you align your choice with specific project objectives.

The table below summarizes the core characteristics of the primary benchmarking approaches available to researchers.

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Protein Engineering Benchmarks

| Benchmark Type | Primary Goal | Typical Outputs | Key Strengths | Ideal Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Community Tournaments [3] [26] [19] | Foster breakthroughs via competitive, iterative cycles of prediction and experimental validation. | - Public datasets- Model performance rankings- Novel functional proteins | - Tight feedback loop between computation & experiment- High-quality experimental ground truth- Drives community progress | - Testing models against state-of-the-art- Generating new experimental datasets- Algorithm development for protein design |

| Uncertainty Quantification (UQ) Benchmarks [4] [13] | Evaluate how well a model's predicted confidence matches its actual error. | - Metrics on uncertainty calibration, accuracy, and coverage | - Assesses model reliability on distributional shift- Informs Bayesian optimization and active learning | - Guiding experimental campaigns- Methods where error estimation is critical- Robustness testing under domain shift |

| Custom-Domain Dataset Benchmarks [7] | Provide high-quality, curated data for training and evaluating models on a specific biological phenomenon. | - Curated positive/negative datasets- Performance metrics on predictive tasks | - High data confidence and interoperability- Clarifies specific protein roles (e.g., drivers vs. clients) | - Developing predictive models for specific mechanisms (e.g., LLPS)- Understanding biophysical determinants of a process |

Inside the Protein Engineering Tournament: A Community Benchmark

Community tournaments like the one organized by Align provide a dynamic benchmarking environment that mirrors real-world engineering challenges [3].

Experimental Protocol and Workflow

The tournament structure creates a tight feedback loop between computational predictions and experimental validation, typically unfolding in distinct phases over an 18-24 month cycle [3].

Predictive Phase: Participants use computational models to predict biophysical properties from protein sequences. These predictions are scored against held-out experimental data to select top-performing teams [3] [19].

Generative Phase: Selected teams design novel protein sequences with desired traits. These designs are synthesized and tested in vitro using automated, high-throughput methods, with final ranking based on experimental performance [3] [26] [19].

Quantitative Performance Metrics

Tournaments employ comprehensive scoring against experimental ground truth. The 2023 pilot tournament involved six multi-objective datasets, with experimental characterization conducted by an industrial partner [26]. The upcoming 2025 tournament focuses on engineering improved PETase enzymes for plastic degradation [3].

Benchmarking Uncertainty in Protein Engineering

For projects relying on Bayesian optimization or active learning, benchmarking your model's uncertainty estimates is as important as benchmarking its predictive accuracy.

Experimental Protocol for UQ Evaluation

A rigorous UQ benchmark, as detailed by Greenman et al., involves several key stages [4] [13].

Dataset and Split Selection: The benchmark uses protein fitness landscapes (e.g., GB1, AAV, Meltome) from the Fitness Landscape Inference for Proteins (FLIP) benchmark. It employs different train-test splits designed to mimic real-world data collection scenarios and test varying degrees of distributional shift [4].

UQ Method Implementation: The study implements a panel of deep learning UQ methods, including:

- Ensemble methods: Multiple models with different random initializations [4]

- Stochastic regularization methods: Such as Monte Carlo dropout [4]

- Evidential methods: That directly model uncertainty in the predictions [4]

- Traditional methods: Including Gaussian Processes and Bayesian Ridge Regression [4]

Evaluation Metrics: The benchmark uses multiple metrics to assess different aspects of UQ quality [4]:

- Calibration: How well the predicted confidence intervals match the actual error (miscalibration area)

- Coverage and Width: The percentage of true values falling within confidence intervals and the size of those intervals

- Rank Correlation: The relationship between uncertainty estimates and actual errors

Quantitative UQ Performance Data

The table below summarizes key findings from a comprehensive UQ benchmarking study, illustrating how method performance varies across different evaluation metrics [4].

Table 2: Uncertainty Quantification Method Performance on Protein Engineering Tasks

| UQ Method | Best For | Calibration Under Domain Shift | Active Learning Performance | Bayesian Optimization |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CNN Ensembles | Robustness to distribution shift [4] | Variable | Often outperforms random sampling in later stages [4] | Typically outperforms random sampling but may not beat greedy baseline [4] |

| Gaussian Processes | Small data regimes | Can be poorly calibrated on out-of-domain samples [4] | - | - |

| Evidential Networks | Direct uncertainty modeling | - | - | - |

| Bayesian Ridge Regression | Linear relationships | - | - | - |

Key Finding: No single UQ method consistently outperforms all others across all datasets, splits, and metrics. The optimal choice depends on the specific protein landscape, task, and representation [4].

Building Custom Benchmarks for Specific Phenomena

For specialized research areas like liquid-liquid phase separation (LLPS), creating custom benchmarks with carefully curated datasets may be necessary.

Experimental Protocol for Dataset Creation

A robust custom benchmark requires meticulous data integration and categorization [7]:

- Data Compilation: Gather data from multiple specialized databases (e.g., PhaSePro, LLPSDB, DrLLPS).

- Standardized Filtering: Apply consistent, stringent filters to ensure data quality and interoperability between sources.

- Role Categorization: Classify proteins by specific roles (e.g., "driver" vs. "client" in LLPS) through cross-checking across source databases.

- Negative Dataset Creation: Define reliable negative examples (proteins not involved in the phenomenon) that include both globular and disordered proteins, which is crucial for unbiased model training.

Performance Metrics for Custom Benchmarks

After creating the benchmark dataset, researchers typically [7]:

- Investigate key physicochemical traits that differentiate positive and negative examples.

- Benchmark multiple predictive algorithms to establish baseline performance.

- Identify limitations in current methods and highlight key differences underlying the biological process.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Resources for Protein Engineering Benchmarking

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Function in Benchmarking |

|---|---|---|

| Benchmark Platforms | Align Protein Engineering Tournament [3] | Provides competitive framework with experimental validation for predictive and generative tasks. |

| Standardized Datasets | Fitness Landscape Inference for Proteins (FLIP) [4] | Offers predefined tasks and splits with varying domain shift to test generalization. |

| Specialized Databases | LLPSDB, PhaSePro, DrLLPS [7] | Provides expert-curated data for specific phenomena like liquid-liquid phase separation. |

| Protein Language Models | ESM-1b [4] | Generates meaningful sequence representations (embeddings) as input features for models. |

| Uncertainty Methods | CNN Ensembles, Gaussian Processes, Evidential Networks [4] | Provides calibrated uncertainty estimates crucial for Bayesian optimization and active learning. |

| Experimental Characterization | Automated high-throughput screening [26] [19] | Generates ground-truth data for computational predictions in a scalable manner. |

| N-phenyl-3-isothiazolamine | N-phenyl-3-isothiazolamine|Research Chemical | N-phenyl-3-isothiazolamine for research applications. This product is for Research Use Only (RUO) and is not intended for personal use. |

| Methyl 4-bromopent-4-enoate | Methyl 4-bromopent-4-enoate|C6H9BrO2 | Methyl 4-bromopent-4-enoate (CAS 194805-62-4) is a versatile bromoester reagent for organic synthesis. This product is for research use only (RUO). Not for human or veterinary use. |

The optimal benchmark for your protein engineering project depends directly on your primary research objective. Community tournaments are ideal for testing against state-of-the-art methods and contributing to collective progress on predefined biological challenges. Uncertainty quantification benchmarks are essential when model reliability and guiding experimental campaigns are paramount. For specialized biological phenomena, investing time in creating or using carefully curated custom benchmarks may be necessary to ensure meaningful evaluation.

By selecting a benchmark with the appropriate structure, data quality, and evaluation metrics, you ensure that your findings are robust, interpretable, and contribute meaningfully to advancing computational protein engineering.

From Data to Design: Methodologies for Leveraging Protein Benchmarks in Practice

The transformation of protein sequences into numerical representations forms the foundational step for applying machine learning in modern bioinformatics and protein engineering. An effective representation captures essential biological information—from statistical patterns and evolutionary conservation to complex structural and functional properties—enabling predictive models to decipher the intricate relationships between sequence, structure, and function. The evolution of these representations mirrors advances in artificial intelligence, transitioning from simple, rule-based one-hot encoding to sophisticated, context-aware embeddings derived from protein language models (PLMs) [27] [28]. These representations are pivotal for tackling protein engineering tasks, such as designing stable enzymes, predicting protein-protein interactions, and annotating functions for uncharacterized sequences, directly impacting drug discovery and biocatalyst development [29] [30].

Within the context of benchmark-driven research, the choice of representation imposes a specific inductive bias on a model. Fixed, rule-based representations offer interpretability and efficiency, while learned representations from PLMs can capture deeper biological semantics from vast unlabeled sequence databases [28]. This guide provides a systematic comparison of representation methods, evaluating their performance, computational requirements, and suitability for specific protein engineering tasks, thereby equipping researchers with the knowledge to select the optimal encoding strategy for their objectives.

Fundamental Encoding Methods: From Manual Features to Learned Representations

The methodologies for representing protein sequences can be broadly categorized into three evolutionary stages: computational-based, word embedding-based, and large language model-based approaches [27]. Each stage embodies a different philosophy for extracting information from the linear sequence of amino acids.

Computational-Based and Fixed-Length Representations

Early computational methods rely on manually engineered features derived from the physicochemical properties and statistical patterns of amino acid sequences [27]. These fixed-length representations are computationally efficient and interpretable, making them suitable for tasks with limited data where deep learning is not feasible.

- One-Hot Encoding: This most basic method represents each amino acid in a sequence as a binary vector of length 20, with a single '1' indicating the identity of the residue and the rest '0's. While simple and devoid of any inherent bias, it provides no information about the relationships or properties of different amino acids and results in high-dimensional, sparse data [31].

- k-mer Composition (AAC, DPC, TPC): These methods transform sequences into numerical vectors by counting the frequencies of contiguous subsequences of length k. For proteins, Amino Acid Composition (AAC) (k=1) counts single residues, Dipeptide Composition (DPC) (k=2) counts pairs, and Tripeptide Composition (TPC) (k=3) counts triplets [27]. The core advantage is the capture of local sequence patterns, which is useful for tasks like sequence classification and motif discovery. A significant drawback is the rapid explosion in dimensionality; TPC, for instance, produces a 8,000-dimensional feature vector (20³), which can lead to sparsity and require dimensionality reduction techniques like PCA.

- Group-Based Methods (CTD, Conjoint Triad): These methods reduce dimensionality and incorporate biological knowledge by grouping amino acids based on shared physicochemical properties (e.g., hydrophobicity, charge, polarity). The Composition, Transition, and Distribution (CTD) descriptor calculates the composition of each group, the frequency of transitions between groups, and the distribution pattern of each group along the sequence, resulting in a compact 21-dimensional vector [27]. The Conjoint Triad (CT) method groups amino acids into seven categories and then calculates the frequency of each possible triad of categories, yielding a 343-dimensional vector that captures both composition and local order [27].

- Position-Specific Scoring Matrix (PSSM): PSSMs incorporate evolutionary information by representing a sequence as a matrix of scores derived from multiple sequence alignments. Each score reflects the log-likelihood of a particular amino acid occurring at a specific position, given the evolutionary conservation observed in related sequences. PSSMs are powerful for structure and function prediction but are computationally intensive to generate as they depend on the quality of the underlying sequence alignment [27].

Word Embedding and Deep Learning-Based Representations

Inspired by natural language processing (NLP), these methods treat protein sequences as sentences and k-mers of amino acids as words. They leverage deep learning to learn dense, continuous vector representations that capture contextual relationships within the sequence.

- ProtVec & Seq2Vec: As a pioneer in this space, ProtVec applies the Word2Vec skip-gram model to a large corpus of protein sequences, treating every overlapping tripeptide (3-mer) as a "word" and learning a 100-dimensional distributed representation for each [32]. An entire protein can then be represented by summing or averaging its constituent tripeptide vectors. Seq2Vec (or Doc2Vec) extends this concept to embed a full protein sequence into a single vector, capturing global contextual information [32].

- UniRep & SeqVec: UniRep utilizes a multiplicative Long Short-Term Memory (mLSTM) network, trained on ~24 million protein sequences, to generate a single 1,900-dimensional vector representation for an input sequence [32]. SeqVec employs the ELMo (Embeddings from Language Models) framework, a bidirectional LSTM, to produce context-aware, per-residue embeddings. These per-residue vectors can be averaged to create a global protein representation [32]. While these models capture more complex sequence context than ProtVec, their recurrent architecture limits parallelization during training.

Protein Language Models (PLMs)